Abstract

This study examines the relationship between tourists’ level of perceived safety in Thailand and their future behavioral intentions to revisit Thailand in a post-COVID-19 context. Moreover, the study also examines the moderating role of a destination’s image and the mediating effects of perceived constraints on the relationship of tourists’ perceived safety and their future behavioral intentions. The aim of this study is to fill gap in the literature regarding the impact of safety perceptions on future sustainable travel intentions. For this purpose, a cross-sectional research design was used, and data were collected through purposive sampling. Structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to analyze the data. A total of 219 tourists participated in the study, of which 122 were male and 97 were female. The results revealed a positive association between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions. Moreover, the moderating effect of a destination’s image on the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions was found to be positive. Additionally, the mediating role of perceived constraint in the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions exhibited a negative effect. While no significant gender differences were observed in most variables, perceived constraints differed significantly between male and female tourists. These results underscore the crucial roles of safety and a destination’s image in influencing tourists’ future travel decisions. By emphasizing safety and positive destination imagery, the findings contribute to sustainable tourism development by promoting long-term visitor engagement, enhancing destination resilience, and supporting the socio-economic recovery of tourism-dependent communities.

1. Introduction

Natural disasters, pandemics, or epidemics can disrupt numerous industries, including tourism, thereby affecting travelers’ plans. Tourists can be affected by pandemics, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, floods, and pandemics, all of which possess the potential to disrupt the tourism sector [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on economic, health, and environmental aspects, as well as social and cultural dimensions in education and tourism [2]. Due to COVID-19, international visitor arrivals were anticipated to decline by 78%, resulting in an estimated loss of income amounting to USD 1.2 trillion. Additionally, approximately 120 million workers lost their jobs [3]. Fear, in proportion to anxiety, increases protective motivation and coping mechanisms during public health crises [4]. The global tourism sector needs to be aware of travelers’ preferences, actions, and interests [5]. The tourism sector, like many other service sectors, is intangible [6]. The experience has limitations, hazards, and dangers (i.e., terrorism, political turmoil, epidemic diseases, psychological trauma, less information, and language barriers). This inherent openness and vulnerability entail the risk of undermining the intended effect [7]. Unlike real experiences, tourists make decisions based on their preconceived notions about a destination [8]. Tourist destinations compete by offering what people perceive as valuable [9]. The image of a destination is meant to represent what it is really like. This image includes different ways people think, feel, and act towards the place. Moreover, emotional and cognitive destination images together create a complete understanding of the location [10].

Another important component in making travel decisions is how people see risks [11]. Natural dangers (such as pandemic diseases and natural disasters) have made tourists more concerned about safety. Natural disasters and epidemic diseases like COVID-19 could make people more scared and restrict the flow of international tourists [12]. Terrorism, political troubles, social issues, economic crisis, and health concerns are all factors that travelers consider when making travel decisions [12]. When making travel decisions, it is important to consider travel constraints in addition to destination perception and risk perception. Perceived restrictions are things that impede you from engaging in a specific behavior [13]. Constraints are more than just obstructions; they can also bring advantages and possibilities [14]. Studies about tourism include both positive and negative images of locations. A positive destination image can be utilized to mitigate perceived risks and constraints. The existing literature has shown that tourists go back to the places despite perceived threats and difficulties [15].

Many international tourists arrived from China, ranking Thailand tenth on the list of countries tourists visited [16]. Thailand had a record number of visitors in 2019, reaching 40 million. Their total spending was divided into lodging (28%), shopping (24%), food and drinks (24%), and then shopping again (24%). Thai tourism generated 36 million jobs between 2014 and 2019 [16]. However, international travel drastically decreased due to COVID-19 vaccination requirements. Travel to Thailand from other countries decreased by 95% in September 2021, with hotel occupancy at only 9%. Furthermore, the pandemic amplified tourists’ concerns about health risks, transforming safety from a peripheral consideration to a central determinant of travel decisions [17]. The pandemic changed the landscape of destination competitiveness in that now perceptions of safety became part of destination branding. Travelers’ post-COVID-19 take into account many perceptions that they did not before the pandemic; however, safety perceptions will become valiant competitors to cost and convenience when planning travel [18]. In an effort to attract foreign visitors, Thailand introduced the “Phuket Sandbox” program in July 2021. Passengers who received essential vaccines and stayed in Phuket for 14 days were exempt from quarantine before traveling to other regions of Thailand. Tourists, in the post-pandemic era, have also appropriately begun to gravitate towards destinations that implement transparent biosecurity policies, such as Thailand’s ‘SHA Plus’ certificate. The SHA Plus certificate indicates compliance with international health standards, therefore signaling trust for tourists [19]. These changes highlight the perceived notion of safety being crucial to gaining trust back for travelers during the post-pandemic era, especially for tourism destinations like Thailand that primarily focus on international tourism [16].

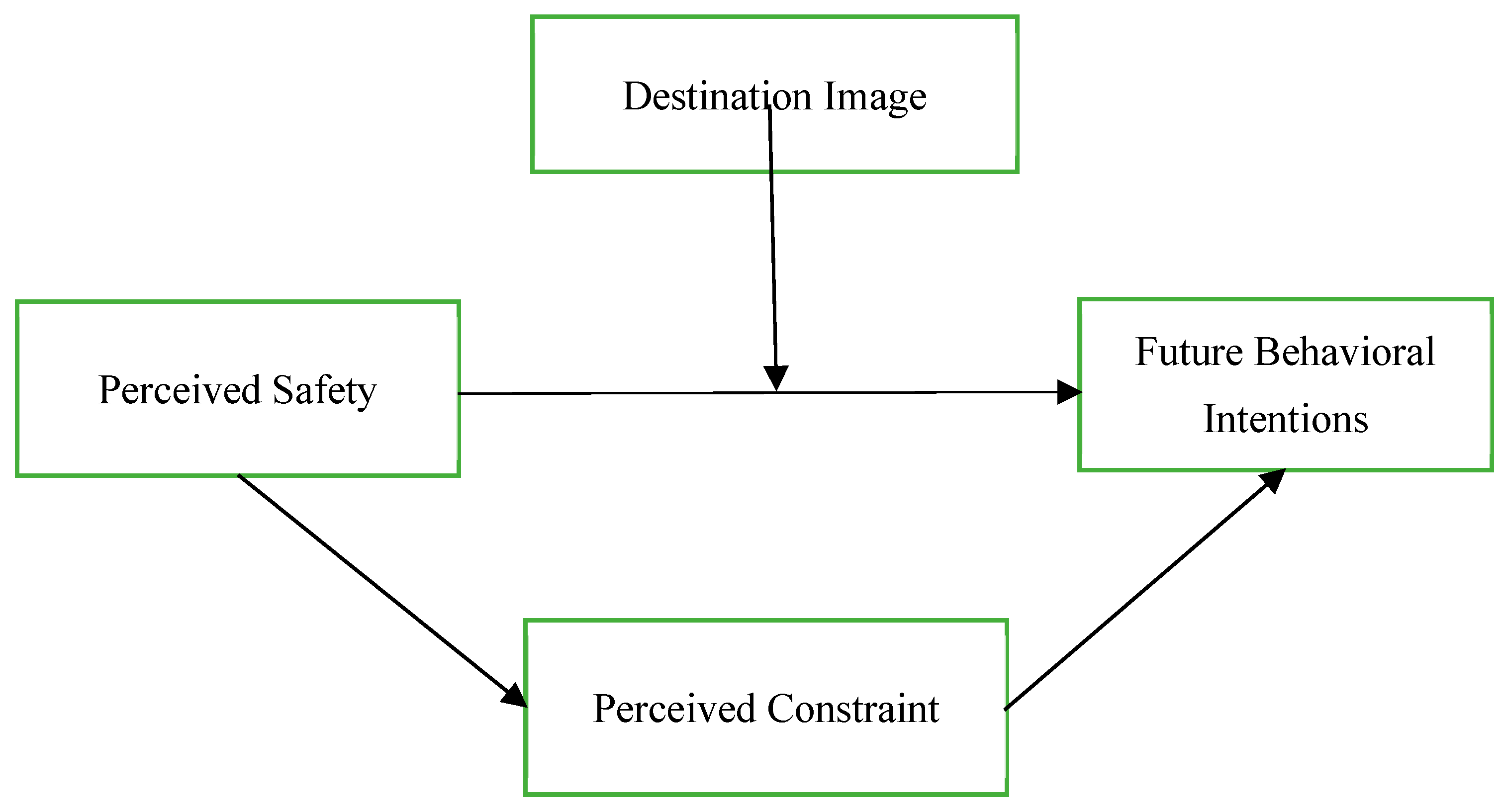

Thus, the current study was designed to examine international tourists’ perceptions of safety and their future intentions to revisit Thailand. Moreover, the destination’s image is used as a moderating variable, and perceived constraint is used as a mediating variable (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study.

- Purpose of Study

This research seeks to understand how international tourists’ perceptions of safety in Thailand influence their intent to revisit Thailand after the COVID-19 pandemic. It narrows the goal of the research to address a gap in the tourism literature, which is to understand not only the direct effect safety perceptions have on behavioral intentions, but how safety perceptions are involved with two factors: the image of Thailand as a destination (which will contribute to either positive or negative perceptions of safety) and perceived constraints (which are misperceptions such as financial constraints, health constraints, etc., that could inhibit a travel plan). The context of the study is based in Thailand, a country where tourism contributed 20% of GDP and which saw a 95% decrease in international tourists during the pandemic, thereby reinforcing the study findings with a purpose in a world needing to restart the tourism economy sustainably. This study uses the Theory of Reasoned Action to explain how tourists’ attitudes and subjective norms (such as what a tourist sees as the social expectation regarding their safety when they travel) converge and can alter behavioral intentions.

- Research Significance

This study presents several important contributions to tourism and behavioral research, especially as we shift into post-pandemic recovery: The research introduces a multi-faceted framework that examines perceived safety, the destination’s image, and perceived constraints together (simultaneously), whereas other studies have examined these factors separately. The model reflects the dynamic ways these variables interact to create travel intentions. The study uses the TRA and creates an entirely new version based on the fact that we all recently experienced a global health crisis. This paper also builds on the TRA by including the pandemic while leveraging a previously established model. This novel addition extends the TRA (which the original authors of the TRA could not have possibly imagined) and explains how crises change the way we weigh safety and risk in our decision making. This adaptation also provides a guide for how to adopt traditional theories in untraditional contexts. Furthermore, by using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) as a new approach to analyzing complex relationships (in our study mediation and moderation), this study shows methodological creativity.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Reasoned Action Theory

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) explains behavior associated with intentions and is utilized in the sectors of marketing, healthcare, and tourism to study human behavior. The TRA is a socio-psychological theory that offers predictions about behavior [20]. According to the theory of reasoned action, a person’s worldview and personal standards determine their behavioral intention, which in turn influences their actual behavior. Therefore, the TRA theory employs attitude and subjective norms to explain behavioral intention [21]. According to Shen and Wu’s [22] TRA paradigm, the primary behavior or action closest to the absolute definition is the intention to act. This is also an element of the attitude towards behavior within the Subjective Norm TPB framework. The TRA predicts how individuals will behave [23]. The behavior of tourists determines whether they will visit a destination. This illustrates that attitude is a broad personal evaluation of individual behavior, which can be positive or negative [24]. Visitors are evaluated based on subjective standards derived from subjective norms [25]. Subjective norms are individual assessments made in social circumstances regarding what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable behavior [25].

The hypotheses in this study draw from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) [20], which suggests that behavioral intentions depend on attitudes (personal evaluations) and subjective norms (social influences). In this context, perceived safety is an individual’s attitude towards Thailand as a destination. The TRA proposes that positive attitudes (e.g., representing Thailand as safe) directly enhance intentions to return [26]. In line with this, the destination’s image acts as a subjective norm, representing society’s or peers’ perception of how appealing Thailand is for the purposes of tourism. The TRA suggests that subjective norms have the capacity to either enhance or diminish the strength of attitudes to predict intentions of travel [27]. So, while the TRA identifies attitudes and norms only, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [27] assumes elements of TRA and adds perceived behavioral control (PBC), which can be understood as “perceived constraints”. Within the TPB, the PBC variable explains how external limitations (e.g., costs to travel or health issues) can mediate the link between attitude and intention.

2.2. Tourist Perception Towards Safety

Individual safety is taken into account when considering visitor safety. Tourists’ perceived safety (TPS) influences travelers’ decision making, satisfaction, confidence/trust, and desire to return. Tourists evaluate safety based on a variety of safety elements that capture their attention [28]. Interactions with people, contact with nature, facilities and equipment, and public safety precautions are all part of this. As a result, this study determined that TPS is a multifaceted construct that includes personnel, facilities, and equipment, as well as the environment, management, and visitors’ perceptions of safety. Assessing tourists’ perceptions of safety is critical in creating a “favorable climate” for tourism expansion. Many studies on visitor safety have been conducted [29]. If tourists decide to proceed, they can change their destination, adjust their travel arrangements, or obtain relevant information. Travel intentions are heavily influenced by perceived danger and safety. However, tourists often avoid high-risk areas [30]. Consequently, unsafe environments may lose their attractiveness and be disregarded [31]. Tourists’ safety influences both destination selection and future intentions to revisit the place.

2.3. Destination Image

According to [32], an image concept comprises human mental representations (beliefs), emotions, and overall perceptions of an object or location. It is difficult to provide a clear picture of the relationship between good and evil. An excellent reputation for a destination contributes to its success, but it can also lead to failure due to excessive expectations. A location’s favorable public reputation encourages visitors to return; however, people might reconsider returning if the quality is poor. In the past it was believed that the perception of a destination was the sole determinant of travel intention. Several individuals have emphasized the importance of destination perception in determining travel intent [33]. An area’s reputation affects travelers’ destination selection, trip evaluations, and future travel plans, indicating that the area’s reputation significantly influences travel intentions. Due to intensifying competition, destinations must have a unique identity. Just as it has been suggested that intentions to visit a location should depend on this image, it makes sense that the perception of a destination is the most significant factor [34]. Furthermore, one study [10] stated that destination expectations differ based on pre- and post-travel phases. Domestic and international visitors perceive a destination’s image differently, and increasing competition and unique location impressions encompass tourism, heritage, and lodgings. Depending on time, duration, and experience, a destination’s image may shift [35]. Additionally, according to [36], involvement in couch surfing increases the destination’s reputation.

International tourists have diverse perceptions of various nations and locations [37]. Perceptions of a destination’s imagery vary among visitors, non-visitors, and experiencers. Value and quality perceptions are highly influenced by a destination’s image [38]. Visitor satisfaction and loyalty are influenced by the perception of a destination. The overall impression is substantially influenced by cognitive and emotional goal images. The cognitive destination image emerges first, followed by the emotional destination image [38]. A mental and emotional image increases the number of visitors to reality program locations. The cognitive, emotional, and distinctive features of the destination picture have a significant impact on its overall perception. The entire destination picture also influences attitudes and behavioral intentions [39]. There are beneficial effects of a country’s image on destination images and substantial effects of both country and destination images on travel intent [9]. The environmental image influences proactive and intrinsic behavior less than the ecological image. Political difficulties, nuclear radiation, barriers to personal safety, and perceptions of risk have a negative impact on reputation for vacation destinations, consequently reducing travelers’ likelihood to return [40]. The perception of a site significantly affects whether people will recommend or revisit that location [41].

2.4. Perceived Constraint

According to Crawford et al. (1991) [42], obstacles or impediments are examples of restrictions. Constraints are barriers that make it challenging to complete a particular activity. Limitations are not always detrimental; they can sometimes be utilized to improve the quality and features of a place. Constraints affect travel activity categories, destination preferences, and frequency. However, while the tourism industry can work around some regulations, others are more challenging because their removal is contingent upon negotiation [43]. Some tourists view travel constraints as an opportunity. Disinterest, personal safety, and institutional hurdles are the obstacles preventing students from visiting the US–Mexico border [44].

There are four types of restrictions for the elderly: intrapersonal, interpersonal, microstructural, and macrostructural [45]. A tourist must contend with a lack of recommendations, structural challenges, and a lack of time, as well as interpersonal and intrapersonal issues. The link between preference level and intrapersonal limitations is extremely negative. However, participation, interpersonal, and structural constraints have little impact on the calligraphic environment. When planning and engaging in actual excursion behavior, travelers should consider interpersonal and academic constraints. Nonetheless, these factors have little impact on the frequency of travel or duration of stay [46]. According to one study, only the perceived incapability component of constraints has a significant impact on learned helplessness, whilst the other dimensions of constraints have a little influence [46].

Health issues have the greatest influence on travel intention, followed by financial and family worries, which hold a greater influence, and time, travel stress, travel companion, and pet concerns, which have a lesser influence. However, work requirements have no impact on the decision to travel [47]. The desire of a disabled individual to travel remains unaffected by innate, environmental, or interaction-based constraints. According to previous research [48], interpersonal restrictions influence the attitudes and travel inclinations of solo travelers. In contrast, attitudes and travel objectives are not affected by structural limitations. Travel constraints significantly affect travel intent, while negotiating travel restrictions has a positive effect on travel intent [47].

2.5. Socio-Economic Condition in Thailand

Tourism in Thailand has experienced marked changes over the years because of world events. Before the pandemic, tourism accounted for about one-fifth (20%) of Thailand’s economy [49], with nearly 40 million international visitors to Thailand in 2019 alone. The COVID-19 pandemic hit Thailand hard: global tourism experienced a −74% fall in 2020, and Thailand experienced an −83% fall in visitors (to 6.7 million) and a loss of USD 62 billion in revenue [50]. Recovery in 2021 was slow (427,869 visitors) due to strict border rules, even with the “Phuket Sandbox” program commencing in July. Thailand was fully open in July 2022, and tourism began to surge. Tourist arrivals reached 11.15 million in 2022—a 2500% increase from 2021. By 2023, recovery picked up pace, with 6.47 million visitors in quarter one alone (1200% increase than just beginning of 2022), primarily from China’s border reopening. Total arrivals in 2023 were over 28 million with USD 34 billion in revenue. Even with challenges like high inflation (peaking at 7.9% in 2022), Thailand expects the return of tourism to pre-pandemic levels (40 million) by 2024 [51].

2.6. Hypothesis of the Research

H1:

Perceived safety has a positive relationship with future behavioral intentions to visit Thailand.

H2:

The destination’s image has moderating effect on the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions.

H3:

Perceived constraints mediate the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intensions.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

A quantitative, cross-sectional design was used in this research to examine tourists’ perceived safety, destination images, perceived constraints, and future behavioral intentions regarding tourism in Thailand in a post-COVID-19 period.

3.2. Sample Size

The sample included international tourists aged 18 and older who traveled to Thailand between July 2022 and December 2022, after the complete reopening of borders. The data were collected using convenience sampling, also known as non-probability sampling, which is used to include members of the target population who fit certain practical characteristics, such as accessibility, proximity to the study site, availability at a specific time, or desire to participate in the study [52]. Participants meeting the inclusion criteria of being a first-time or repeat visitor to Thailand after the pandemic and staying in Thailand for a minimum of 3 days were recruited using convenience sampling. A power analysis using G*Power (α = 0.05, effect size = 0.15, power = 0.95) indicated that 196 would be the minimum sample size needed. To account for attrition, 320 participants were recruited. There were 320 participants in the survey, but 101 participants were eliminated due to insufficient data.

3.3. Procedure

After the COVID-19 pandemic, when tourists were allowed to visit places across the border and wanted to visit Thailand, data for this study were collected. Visitors were asked to fill out a survey about how safe and free they felt, how they planned to interact with people, and whether they planned to travel to Thailand in the future. Detailed standard operating procedures were adhered to during data collection. The researcher and his assistant collected data from different locations; beaches (26%), lakes (20%), and other monuments (historic sites, mountains, and restaurants 52%). Participants were asked to describe their most recent weekend excursion to a tourist site, and both men and women who desired conversation were present. The responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale for the data examination.

3.4. Research Instruments

- Participants’ information sheet: In the present study, tourists’ general information (gender, tourist age, country, frequency of travel) was collected.

- Tourist perceived safety: In the current study [53], a five-dimensional scale (natural and social environment, human safety, facilities and equipment, and management) was used. In which tourists rate the response on a 5-point Likert scale. The scale had 20 items. The scale had 0.81 reliability.

- Tourist perceived constraint: A 10-item Likert scale was used to measure the extent of tourist constraints during the visit to Thailand after the pandemic [54]. The scale had 0.81 reliability.

- Future behavioral intention: A 3-item Likert scale was used to measure tourists’ intentions to visit again in Thailand [55]. The scale had 0.86 reliability.

- Destination’s image: An 11-item Likert was used to measure Thailand’s tourist destination image after the pandemic [56]. The scale had 0.79 reliability.

3.5. Data Analysis

PLS (SEM), which stands for structural equation modeling using partial least squares, was also utilized to examine the data.

4. Results of the Study

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the study participants. The total sample comprised 219 tourists, with males representing 66% and females comprising 33%. The mean age of the participants was 42 years. The majority of tourists visited Thailand either with friends (58%) or family (42%), and a significant proportion of them were married. Additionally, the majority of respondents (63.4%) indicated that they stayed in Thailand for six to ten days. Similarly, 57.9% of visitors to Thailand were first-time visitors.

Table 1.

Tourist Participant information sheet (N = 219).

The AVE and CR values are shown in Table 2. Using Smart PLS 3.2.6, the measurement model for this investigation was evaluated. The measurement model was assessed for its individual item reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The loading factor for all constructions was product dependability [57]. Each model component’s item dependability was unique. Components with dependability ratings above 0.30 must be kept in the model (Hair et al., 2019 [57]). If removing an item increased AVE or CR, it must be removed [58]. While eliminating items had no influence on AVE or CR during this test, none were deleted. Composite reliability was used to determine internal consistency reliability (CR). Each component determined a model’s concept similarity [57]. Internal consistency and dependability were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and CR. The prevalence of CR in evaluating internal consistency was reliable. According to [57], the CR value must exceed 0.70. The CR in this study was greater than anticipated. In our investigation, AVE was utilized to determine convergent validity. Thus, AVE must be more than 0.50 to evaluate convergent validity.

Table 2.

Factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE).

Discriminant validity is a measure of how different one construct is from others. In this study, the discriminant validity was checked in three ways. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was then used to judge the discriminant validity [59]. Cross-loadings can also be used to test a model’s ability to distinguish between groups. Each structure must be worth more than the weight it shares with other structures. Lastly, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) can be used to measure a test’s ability to distinguish between groups of people [60]. The HTMT ratio is a correlation between two variables that can tell them apart. So, Table 3 shows the Fornell–Larcker criteria, and Table 3 displays correlations of the latent variables, including future behavioral intentions, perceived constraints, perceived safety, and the destination’s image. Future behavioral intentions demonstrate a correlation of 0.717 with perceived constraints and 0.707 with perceived safety. Additionally, future behavioral intentions demonstrate a strong correlation with the destination’s image, at a correlation of 0.81. Perceived constraints demonstrate a correlation of 0.698 with perceived safety and a correlation of 0.734 with the destination’s image. Perceived safety and the destination’s image are correlated moderately at a value of 0.762. The relationship between perceived safety and perceived constraints has the highest correlation with a value of 0.841. Table 4 shows the cross-loadings, and Table 5 shows the HTMT ratio.

Table 3.

Correlations of latent variables.

Table 4.

Cross-Loadings.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT)—matrix.

In Table 6, we checked the significance of the study variables from the values of beta, t-value, and p-values. The results revealed that perceived safety has a positive association with future behavioral intentions (β = 0.210; t = 4.530; p < 0.000), which means that perceived safety has a significant effect on tourists’ future behavioral intentions. Moreover, the destination’s image positively moderates the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions (β = 0.197; t = 4.475; p < 0.000). Furthermore, in the current study, perceived constraint negatively mediates the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions (β = −0.146; t = 2.016; p < 0.044).

Table 6.

Assessment of structural model with moderating and mediating effects.

Table 7 presents the gender differences across variables. Regarding perceived safety (TPS), there was no evidence of difference between males (mean = 4.46) and females (mean = 4.48), with t = −0.26; p = 0.79. In the case of constraints (TPC), there was a difference where females (mean = 3.87) identified greater constraints in comparison to males (mean = 3.51), with t = −4.85; p = 0.00. No gender difference was found for the destination’s image (DI) variable (males = 4.52, females = 4.55; t = −0.30; p = 0.77). Similarly, future behavioral intention (FBI) did not present a significant difference, with males (mean = 4.69) having a slightly higher score than females (mean = 4.66) with t = 0.43; p = 0.67. Therefore, the analysis suggests that gender had little to no bearing on the perceived safety, destination’s image, or future intention to travel. However, gender difference did exist in perceived constraints, with females reporting greater constraints than males. Thus, both genders may have similar perceptions of safety or the destination’s image; however, females may be more likely to face and feel far more hindered by constraints when thinking about travel.

Table 7.

Gender differences.

5. Discussion

This study examines the factors that impact visitors’ decisions to travel to Thailand following the pandemic outbreak. The construct from the Theory of Reasoned Action influenced travel decisions. This study should be read by all government authorities, tourist industry experts, and other interested parties in order to recognize the behavior and desire to visit a place following a pandemic and plan accordingly. According to specialists, the research paradigm provided in this study may offer new light on the empirical growth of the tourism industry in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The study examined the relationship between perceived safety and tourists’ future behavioral intentions to visit Thailand again, and our study result confirms that tourists perceive safety when visiting Thailand after the pandemic. This study found that this crucial issue no longer has a substantial impact on people’s travel intentions. Numerous important factors contribute to this trend. One probable explanation is that the novel COVID-19 Omicron variations exhibit much lower mortality rates than the original strains [61]. It is worth noting that booster dosage policies, as well as the high immunization coverage percentage, have been successfully implemented [62]. This trend of greater confidence among travelers is consistent with the research of [63], who observed that people were more willing to travel upon becoming able to travel again following prolonged social isolation and restriction on mobility, despite their concerns regarding the virus. This shows that some of the public’s initial concerns when the pandemic began have evolved over time into more positive behavioral intentions, through factors such as access to vaccines and the perception of lower infection risk [63]. This is consistent with more recent research conducted by [64], which revealed that the trends of a higher level of vaccination and a better understanding of the virus acted as key factors alleviating travel anxieties and positively influencing travel intentions during the pandemic. Ref. [64] also pointed to a psychological shift in travelers from fear to safety because of successful interventions by governments such as health protocols and travel actions, which increased the confidence of travelers.

Moreover, the destination’s image positively moderates the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions. The findings of this study corroborate those of earlier research. The study findings indicated that the intention to return to a place was significantly and favorably influenced by the destination’s image [65]. Ref. [66] indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has sensitized travelers to a destination’s image, especially with regards to hygiene and the perceived likelihood of transmission of infection. They conclude that destinations that retain a positive health-related image will welcome more tourists when travel resumes. In addition, ref. [67] found that destinations that market their safety pledge and recovery from the pandemic will outperform others in terms of tourist arrivals. Our study contributes to the literature by demonstrating that the image of Thailand as a safe and well-managed destination continues to raise positive behavioral intentions toward potential tourists, even though safety considerations have diminished over time.

Furthermore, perceived constraints negatively mediate the relationship between perceived safety and future behavioral intentions. Previous research [68,69] has shown that since perceived constraints have a negative impact on behavioral intentions and destination images, repeat visitors may benefit from lower travel costs. Destination management companies should focus on marketing efforts to attract attention. Destination managers should work on improving infrastructure, the environment, food, and safety. Flights, family holidays, and motels should all be considered as alternatives to mitigate tourist risk.

In our study, we examined gender differences on the scale of study variables. The study’s results on gender differences (Table 7) demonstrate only significant differences in male and female tourists’ constraints. Males represented 66.2% of the study sample (219 in total), more than females at 33.8%. The analysis suggests no difference between male and female perceived safety in Thailand, destination image, or future intention to travel. However, a gender difference did exist in perceived constraints, with females reporting greater constraints than males; females feel far more hindered by constraints when thinking about travel. The gender differences in the current study are in line with earlier research that found that males are usually more confident and perceive lower risks than females [70]. Similarly, ref. [71], found that female travelers expressed heightened levels of concern about health and safety risks during the pandemic—which may explain why females in the study expressed greater concerns about perceived constraints (e.g., health constraints and financial constraints) mediating their travel intentions. These constraints did negatively mediate their intention to revisit Thailand, consistent with the findings of [47], which indicated that more Malaysian female tourists have delayed travel intentions because of fears and anxiety during the pandemic.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has indicated the substantial influence of perceived safety on tourists’ intentions to revisit Thailand after COVID-19, with a significant positive relationship noted. The findings have also indicated the importance of a robust destination image, as it enhanced this relationship to a strong positive association, which was moderated by the perceived limitations that tourists face. Overall, both male and female tourists have had positive experiences while visiting Thailand post pandemic, with no significant differences between men and women. On the scale of perceived constraint, females show higher scores. The implications for destination management are insightful in that promoting perceived safety and a positive destination image will cultivate loyal visitors who wish to return to Thailand and will contribute to further tourism and visitation.

5.2. Practical Implications for Tourist Management Organizations

According to the survey, travelers have a positive view of Thailand’s safety, but some potential visitors are concerned.

- We provide advice to tourism management organizations regarding tourists’ impressions of safety, a destination’s image, and future intentions. The study examined how tourists’ perceptions of tourism safety influence the image of a destination, which in return affects tourists’ enjoyment, future intentions, and tendency make recommendations. In order to enhance tourist pleasure and loyalty, tourist management organizations should focus on managing variables related to tourists’ perceptions of safety, especially in cases of tourism services with lower safety levels. Advertising and promotional efforts for a location should be targeted towards tourists who have a negative perception of the destination’s safety. Providing timely and accurate tourism information, as well as raising awareness about the destination’s safety, are crucial steps. Understanding how tourists evaluate places in terms of perceived constraints and the destination’s image is essential. As a result, destination marketers can increase market share and visitor loyalty by addressing negative perceptions and nurturing positive ones.

- Second, the study found that the majority of visitors held a more positive perception of safety and the destination’s image. Thailand provides travelers with a safe and enjoyable experience, thus avoiding the discrepancies between its positive image and actual experience [72]. In order to enhance Thailand’s safety and tourism appeal, tourism management organizations should work on promoting the destination’s image. Tourists should analyze and provide feedback to identify and rectify any flaws in order to improve the destination’s reputation. Additionally, tourism is susceptible to natural disasters, accidents, public health, social security, and other security-related matters [72]. A safety-related incident could severely damage a tourist destination’s long-standing reputation. Hence, tourist management organizations should proactively address these issues during destination image development, making a concerted effort to monitor and manage detrimental tourist perception. Addressing tourism safety issues should be incorporated into destination management systems and marketing plans, including crisis management strategies.

- Familiarization tours, cultural events, and activities can encourage travelers. In order to improve the destination’s reputation, officials and destination management must work to reduce the perception of political danger.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

This research has some limitations. Firstly, constructing causal conclusions may not be feasible in cross-sectional research. Future studies should utilize longitudinal data to gain a deeper understanding of change over time and establish causality among the examined constructs. Secondly, the study did not evaluate how age and experience influence perceived constraints and destination images. Research indicates that images and perceived constraints can differ based on tourist demographics. Additionally, future research should examine how visitor demographics influence the link between perceived constraints, images, and behavioral intentions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Methodology, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Software, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Validation, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Formal analysis, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Investigation, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Data curation, M.A.-E.-Y.; Writing—original draft, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Writing—review & editing, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Visualization, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Supervision, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B.; Project administration, M.A.-E.-Y., V.P., R.B. and I.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is exempted from ethical review board, as the study is voluntary and did not contain any sensitive information. Moreover, according to National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) the studies which have minimal risk subject to human re-search do not require any ethical approval. Therefore, the ethical approval for this study is waived.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from each individual involved in the study, and it was clearly stated on the questionnaire that data will be used for educational purposes only.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, B.; Niyomsilp, E. The Relationship Between Tourism Destination Image, Perceived Value and Post-visiting Behavioral Intention of Chinese Tourist to Thailand. Int. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaque, I.; Muhammad Riaz Khan Zahra, R.; Syeda Manal Fatima Ejaz, M.; Tauqeer Ahmed Lak Rizwan, M.; Awais-E-Yazdan, M. Prevalence of Coronavirus Anxiety, Nomophobia, and Social Isolation Among National and Overseas Pakistani Students. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. [JPSS] 2022, 30, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO World Tourism Barometer, English version; E-Unwto.org. 2020. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/loi/wtobarometereng (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Sawangchai, A.; Raza, M.; Khalid, R.; Fatima, S.M.; Mushtaque, I. Depression and Suicidal ideation among Pakistani Rural Areas Women during Flood Disaster. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 79, 103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of halal-friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-B.; Kwon, K.-J. Examining the Relationships of Image and Attitude on Visit Intention to Korea among Tanzanian College Students: The Moderating Effect of Familiarity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongrat, E. Destination Branding, Destination image and Influenced by Destination Selection oleh Meeting Planners Existing Destination. J. Event Travel Tour Manag. 2021, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P.; Laesser, C. Destination logo recognition and implications for intentional destination branding by DMOs: A case for saving money. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaulagain, S.; Wiitala, J.; Fu, X. The impact of country image and destination image on US tourists’ travel intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Santana, J.D.; Beerli-Palacio, A.; Nazzareno, P.A. Antecedents and consequences of destination image gap. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Khan, F.; Amin, S.; Chelliah, S. Perceived Risks, Travel Constraints, and Destination Perception: A Study on Sub-Saharan African Medical Travellers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña, L.; Prats, L.; Camprubí, R. Image and risk perceptions: An integrated approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.U.; Yasin, I.; Tat, H.H. Destination image’s mediating role between perceived risks, perceived constraints, and behavioral intention. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.-K. Repeat visitation: A study from the perspective of leisure constraint, tourist experience, destination images, and experiential familiarity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-M.; Su, J.-Y.; Wang, C.-H.; Kiatsakared, P.; Chen, K.-Y. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Mediating Role of Destination Psychological Ownership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxon, S.; Sodprasert, J.; Sucharitakul, V. Reimagining Travel: Thailand Tourism After the COVID-19 Pandemic|McKinsey. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/reimagining-travel-thailand-tourism-after-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepez, C.; Leimgruber, W. The evolving landscape of tourism, travel, and global trade since the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Glob. 2024, 8, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Kozak, M.; Wen, J. Seeing the invisible hand: Underlying effects of COVID-19 on tourists’ behavioral patterns. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Kruglanski, A.W. Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 126, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Wu, Y. The moderation of gender in the effects of Chinese traditionality and patriotism on Chinese domestic travel intention. Tour. Rev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Aziz, N.A.; Ngah, A.H. How does face culture influence Chinese Gen Y’s outbound travel intention? Examining the moderating role of face gaining. Tour. Rev. Int. 2021, 25, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J.; Yang, C.; Mandell, D. Attitude theory and measurement in implementation science: A secondary review of empirical studies and opportunities for advancement. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadiat, A.; Maydiantoro, A.; Dwi Kesumah, F.S. The Theory of Planned Behavior and Marketing Ethics Theory in Predicting Digital Piracy Intentions. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2021, 18, 679–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and the Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic Processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Johnson, L.W. Effects of perceived safety, involvement and perceived service quality on loyalty intention among ride-sourcing passengers. Transportation 2021, 48, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Arcodia, C. Generation Z: Young People’s Perceptions of Cruising Safety, Security and Related Risks. In Generation Z Marketing and Management in Tourism and Hospitality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Ruan, W.J.; Pabel, A. Understanding tourists’ protection motivations when faced with overseas travel after COVID-19: The case of South Koreans travelling to China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 1588–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.; Mohammadi, Z.; Agarwal, M.; Kamble, Z.; Donough-Tan, G. Post COVID-19: Cautious or courageous travel behaviour? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S.; Jovanović, T.; Vujičić, M.D.; Morrison, A.M.; Kennell, J. What Shapes Activity Preferences? The Role of Tourist Personality, Destination Personality and Destination Image: Evidence from Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Oh, Y.; Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.-H. The Moderating Roles of Destination Regeneration and Place Attachment in How Destination Image Affects Revisit Intention: A Case Study of Incheon Metropolitan City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Singh, H.; Mansor, N.N.A. Impact of Perception of Local Community and Destination Image on Intention to Visit Destination; Moderating Role of Local Community Attitude. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 2006–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, S.; Jin, H.S.; Kotsi, F. There is nothing so practical as good theory for tracking destination image over time. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 14, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhzady, S.; Çakici, C.; Olya, H.; Mohajer, B.; Han, H. Couchsurfing involvement in non-profit peer-to-peer accommodations and its impact on destination image, familiarity, and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Tseng, C.; Chen, Y. How Country Image Affects Tourists’ Destination Evaluations: A Moderated Mediation Approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 42, 904–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlozi, S. Loyalty program in Africa: Risk-seeking and risk-averse adventurers. Tour. Rev. 2014, 69, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Heidari, A. Comparing face-to-face and electronic word-of-mouth in destination image formation. Inf. Technol. People 2017, 30, 710–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H. Chinese Tourists’ Perception of the Tourism Image of North Korea Based on Text Data from Tourism Websites. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, J.; Severt, K. Importance of destination marketing on image and familiarity. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.W.; Jackson, E.L.; Godbey, G. A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.Y.; Lantai, T. Understanding travel constraints: An exploratory study of Mainland Chinese International Students (MCIS) in Norway. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdell, J.; Ghoshal, A. US–Mexico border tourism and day trips: An aberration in globalization? Lat. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 24, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.; Milne, S.; Hyde, K.F. Conceptualizing Senior Tourism Behaviour: A Life Events Approach. Tour. Stud. 2019, 19, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, N.F.; Ritchie, B.W. Understanding travel behavior: A study of school excursion motivations, constraints and behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.; Long, F. To travel, or not to travel? The impacts of travel constraints and perceived travel risk on travel intention among Malaysian tourists amid the COVID-19. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 21, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M.; Bauer, A.; Ritchie, W.B.; Passauer, M. The impact of travel constraints on travel decision-making: A comparative approach of travel frequencies and intended travel participation. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Economic Impact Report 2020; World Travel & Tourism Council: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Ministry of Tourism and Sports. Tourism Statistics 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.mots.go.th/news/category/592 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Bloomberg. 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Taherdoost, H. Sampling methods in research methodology: How to choose a sampling technique for research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, J.; Morrison, A.M. Developing a Scale to Measure Tourist Perceived Safety. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 1232–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Khan, F.; Amin, S. Perceived risks, travel constraints and visit intention of young women travelers: The moderating role of travel motivation. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Theory of Planned Behavior: Potential Travelers from China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Lee, C.-K. Examining Chinese College Students’ Intention to Travel to Japan Using the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior: Testing Destination Image and the Mediating Role of Travel Constraints. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 34, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Awais-E-Yazdan, M.; Ilyas, M.A.; Aziz, M.Q.; Waqas, M. Dataset on the safety behavior among Pakistani healthcare workers during COVID-19. Data Brief 2022, 41, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grégoire, Y.; Fisher, R.J. The effects of relationship quality on customer retaliation. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Tsionas, E.G.; Devaraj, S. EHR Investments, Relative Bed Allocation for COVID-19 Patients and Local COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates: A Simulation and An Empirical Study. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaque, I.; Dasti, M.R.; Mushtaq, M.; Ali, A. Attitude towards COVID-19 Vaccine: A Cross-Sectional Urban and Rural Community Survey in Punjab, Pakistan. Hosp. Top. 2021, 101, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Bao, J.; Tang, C. Profiling and evaluating Chinese consumers regarding post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Pan, J.; Zhang, J. Crowding and vaccination: Tourist’s two-sided perception on crowding and the moderating effect of vaccination status during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 24, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, C.E.; Hermanto, Y.B.; Suwito, B. The Effect of Tourist Destination Image (TDI) on Intention to Visit through Tourism Risk Perception (TRP) of COVID-19 in the Tourism Industry in the New Normal Era in Indonesia: Case Study in East Java. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.; Mostafa Seyfi, S.; Rastegar, R.; Hall, C.M. Destination image during the COVID-19 pandemic and future travel behavior: The moderating role of past experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Jamaludin, A.; Zuraimi, N.S.M.; Valeri, M. Visit intention and destination image in post-COVID-19 crisis recovery. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2392–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.T.; Al-ansi, A. Risk assessment of halal products and services: Implication for tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.; Milne, S.; Hyde, K.F. Constraints and facilitators for senior tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jęczmyk, A.; Uglis, J.; Zawadka, J.; Pietrzak-Zawadka, J.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Kozera-Kowalska, M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagöz, D.; Işık, C.; Dogru, T.; Zhang, L. Solo female travel risks, anxiety and travel intentions: Examining the moderating role of online psychological-social support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Wu, J. Influence of Tourism Safety Perception on Destination Image: A Case Study of Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).