Designing for Digital Education Futures: Design Thinking for Fostering Higher Education Students’ Sustainability Competencies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Challenge-Driven Education for Sustainability in Higher Education

2.2. Design-Based Learning and Design Thinking for EfS

2.3. Research Motivation: Design Thinking for Sustainability Competencies

3. Methodology

3.1. Student Designers

3.2. Design-Based Learning Context

- Environmental sustainability, learning, and design.

- Interaction design approaches and traditions for involving users, such as participatory and co-design.

- Hybrid artefacts and their digital-physical materials, countering the designers’ natural inclination to seek out screen-based technologies, as evidenced in previous years of teaching the module.

3.3. Co-Designing with Children in Rural Oxfordshire

3.4. Pedagogical Support Embedded in the Design Thinking Process

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

- A visual Miro board summarising the themes from their literature review;

- Four design PowerPoint presentations were created during the design process (for empathise/define, ideate, prototype, and test phases), inclusive of their design methods and visual outputs;

- An interactive prototype developed within Figma and/or BBC micro:bit.

4. Findings

4.1. Team 1: Children’s Nature Affective Connection

4.1.1. Introducing the Pet Plant Prototype

4.1.2. Problem Diamond: Bringing the Children’s Sociocultural Context in Conversation with the Literature

Today’s children risk experiencing alienation due to urbanisation […] [47], which causes a lack of understanding of nature and our relationship towards it, which is responsible for current severe sustainability issues [49]. Therefore, there is a need for […] an increased exposure to nature and positive experiences in the natural world to improve one’s connectedness to nature [48](empathise/define phase, PowerPoint slides)

“How might we encourage children to change how they view and interact with nature?”(empathise/define phase, PowerPoint slides)

Melanie: I assumed [children] would be similar to how I was as a kid and how it was aligned with the literature, but they were the opposite of what I assumed they would be. They were aware of their emotions and very articulate.(empathise/define phase, weekly group chat)

Melanie: Their connection with nature is limited to the aesthetic aspect of it, instead of actually going into it.

Rihana: Yeah, […] they are interacting in nature, but not with nature… with others in nature, but not with nature.

Ying: I had an assumption that kids in the UK always interact with nature, unlike kids in my hometown, but it turns out that they would only “appreciate” nature. Like: “Ohh, nature is beautiful, and nature is good”, but they would also think that our soil is dirty… that was out of my expectation.(empathise/define phase, weekly group chat)

Melanie: We were conflicted. Half of our group was like, “Include parents!”, and half was like, “No, don’t include parents!” […] So, we wanted to look at literature, like, evidence on it.(empathise/define phase, weekly group chat)

“How might we encourage children to change how they view and interact with nature?”…

“How might we encourage parents and children to understand nature better and their interactions with it to nurture an affective relationship?”(empathise/define phase, PowerPoint presentation)

Daksha: I do remember all of us just [discussing] and me going down that rabbit hole and then just taking that question in different directions, but I don’t think it was an issue. I think it was just all of us thinking, and me being the person who would read it like a lot more. I was going into my rabbit hole, but I think it really helped when we all just talked about what exactly we meant by certain things, so that we could have worded it better, which is where asking and following up with questions, no matter how annoying that entire 10 min was, it really did help for us to understand what we’re not talking about and what we need to focus on.(empathise/define phase, weekly team chat)

4.1.3. Solution Diamond: Embracing Three Design Dilemmas

Rihana: Most of the activities the children did in nature were passive, like cycling or playing football […] After Ideation, we got an idea about […] allowing them to go into nature and interact using an app to guide them.

Melanie: We wanted to focus on the natural activities they’re already doing, but […] adding more meaning to them.(ideation phase, weekly team chat)

Rihana: [We] realised it is possible to include technology and make children go outdoors and interact with each other […], but it is easier to bring nature inside and include technology at the same time.(Final focus group)

When children interact with plants more, they learn how to problem-solve and care for their plants. This increases [children’s] exposure to nature and their interest in environmental protection and pro-conservation behaviours [48,56,57].(ideation phase, PowerPoint presentation)

Ying: They didn’t make the association between the pet and the cactus. They just simply forgot about the plant.(Final focus group)

Melanie: How does the app support children to form an affective relationship with their plants, and like if they would feel more responsible…? They all said yes, but we don’t know if it’s because of the dog. If the dog had any role in it, or was just because they knew what was going on through the (plant) indicators.(Final focus group)

4.2. Team 2: Children’s Fashion

4.2.1. Introducing the Fashion Turtles Prototype

4.2.2. Problem Diamond: Non-Specific Literature Review Before User Research Derails Design Goals

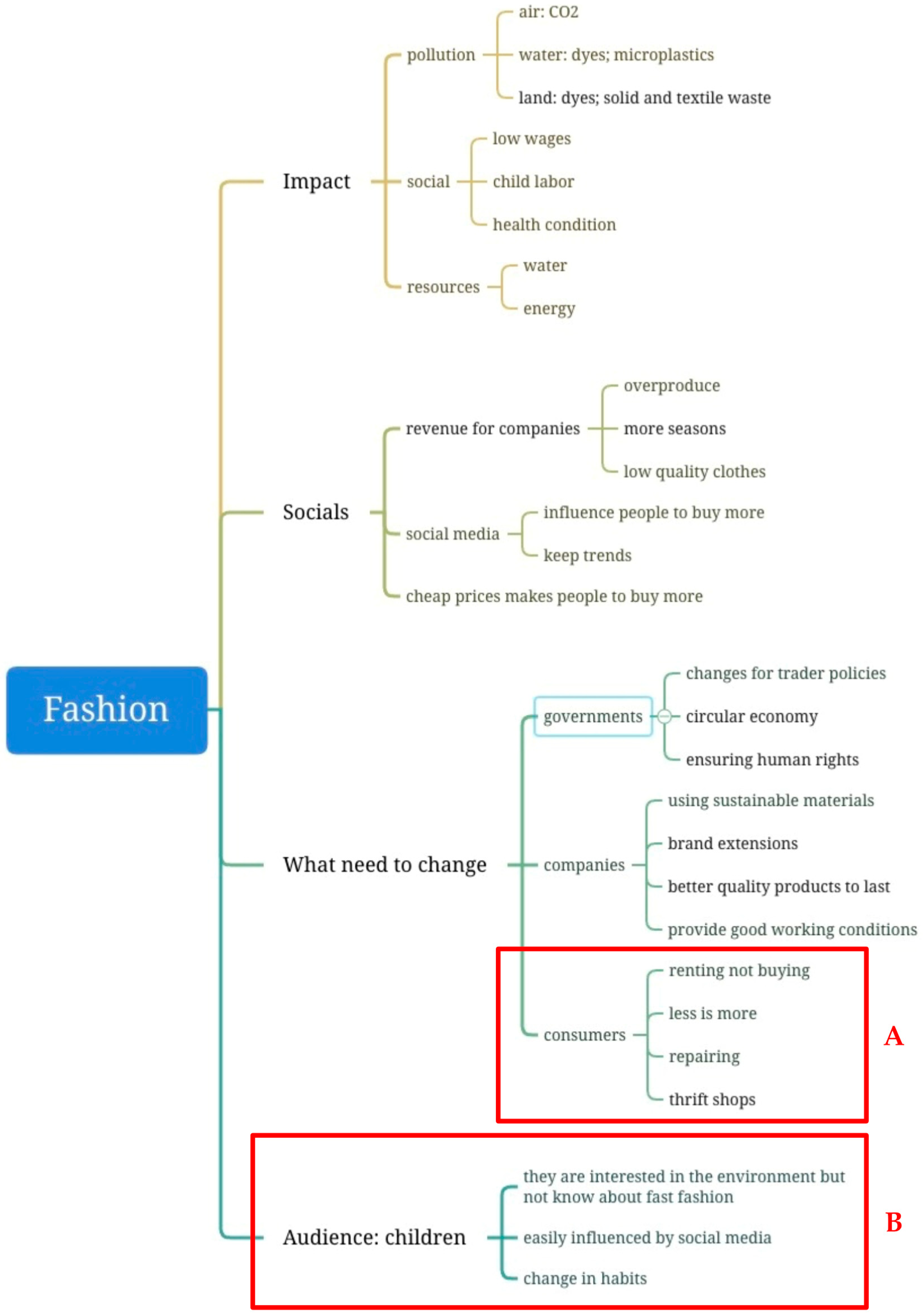

People throw them away instead of repairing them [clothes] (habits). [Clothing] contains toxic substances, and [fast fashion] leads to pollution (environmental impact), and there are bad working conditions for producing cheap [fast fashion] products (social impacts).(empathise/define phase, Miro board)

“What are the children’s experiences with upcycling and repairing? What do they do with clothes that cannot be worn anymore?”(empathise/define phase, PowerPoint slides)

Angelina: “I think that it’s surprised me how much they knew about a subject that I thought they did not know about”.

Sabine: “I think that one challenging thing is that we thought that the kids would be more interested in fashion. Like they had an actual interest, which they didn’t. But it was based on our experiences, it wasn’t from the literature”.(empathise/define phase, weekly group chat)

Stefania: “Our literature review consisted of so many comprehensive different parts. We talked about economy, for instance, and circular economy, and stuff like that. And none of these were relevant for [the children] because they had no idea, because they have never mentioned anything beyond the production of the material [for clothing]”.

Angelina: “…the literature review about how kids and parents use their time… We didn’t look into that and, when we got to [user] research, we saw that they didn’t spend that much together and doing these kinds of things [repairing, upcycling, recycling]”.(empathise/define phase, weekly group chat)

Stefania: “For me, I was surprised that whatever we thought before that would work with [the children]—repairing, upcycling, and recycling—none of these can straightforwardly work for us anymore, and the data [we] gathered were quite different from what we expected in general. I thought there would be some corrections, but it was quite astonishing that everything was quite different from what we expected”.

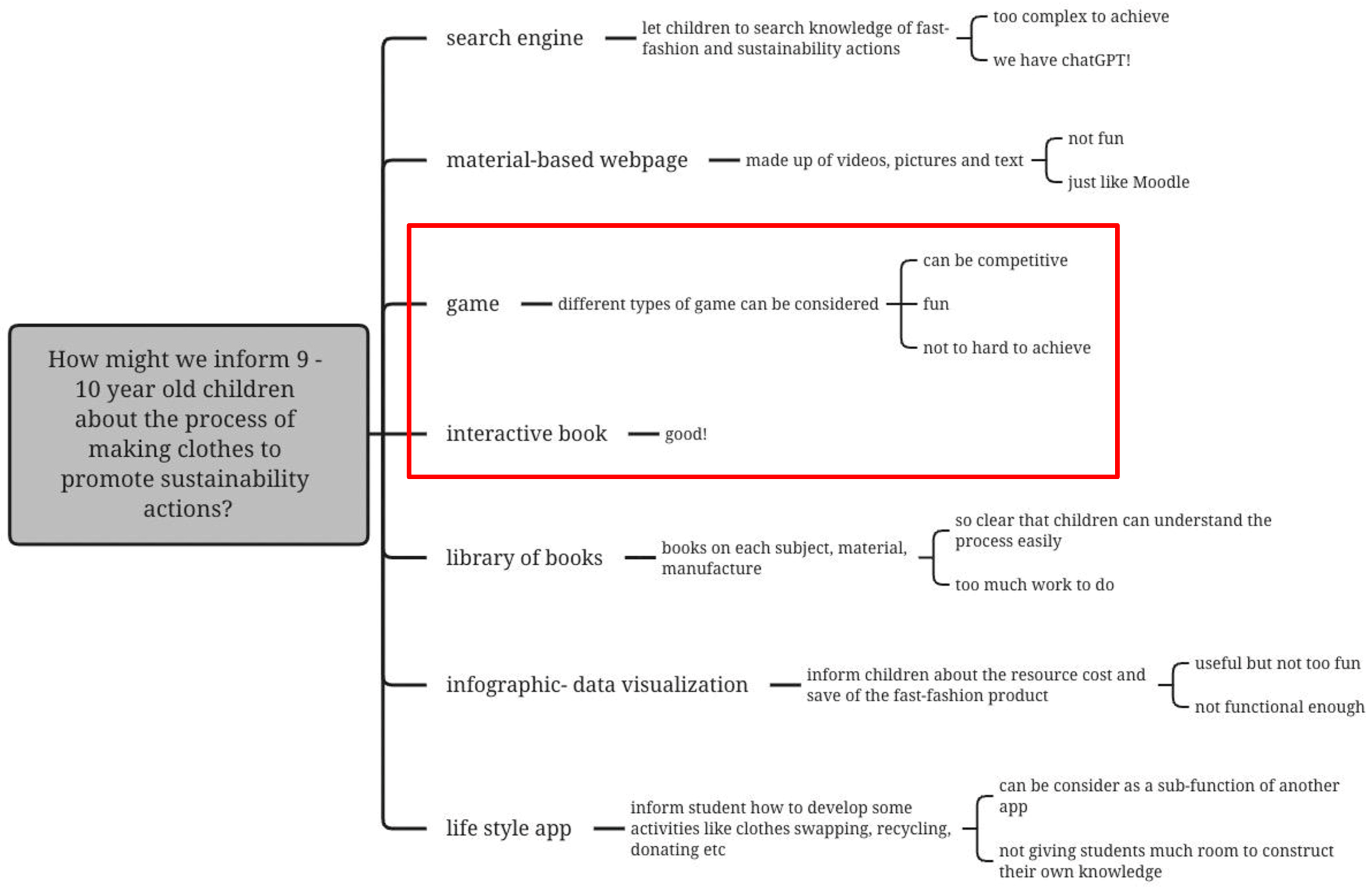

How might we inform 9–10-year-old children about the process of making clothes to promote sustainability actions?(ideation phase, PowerPoint presentation)

Angelina: We did get stuck with recycling and…

Stefania: [Interruption] We had the discussion.

Sabine: Exactly, I think…

Angelina: [Interruption] We had a lot of resistance on your part […].

Sabine: We all had a gut feeling that it wasn’t it, but we couldn’t find the right answer.(empathise/define phase, weekly group chat)

4.2.3. Solution Diamond: General Criteria Informing Design Choices

Sabine: We rejected the ideas, such as the search engine, because we thought it would be hard for the kids [to understand]. We also rejected the idea of only visualising data or displaying information because they wouldn’t be engaged with it.

Barack: I wasn’t necessarily enthusiastic about the digital book, [but] I was more worried about the complexity of prototyping a game, so I thought the book was simpler and easier(ideation phase, weekly group chat)

Angelina: Here is the welcome page for the trivia you start, and you have these different questions […] If you answer it wrong […], you can get a hint and try again until you get it right. […] Then you move to the next level […]. The learning part is not only like the questions but also facts they can learn from [the activities].(prototyping phase, weekly group chat)

Stefania: You [child] know it [fast fashion] more and you are able to explain to the other people more and it also helps, you know, influencing others. That’s how we try to… that’s where our political values that we tried to put into this(Final focus group)

5. Discussion

5.1. Sustainability Competencies Fostered During DT

5.2. DT Practices That Fostered or Hindered Sustainability Competencies

- Undertaking a broad and user-centred (i.e., specific to children) review of the sustainability literature to shape the project;

- Performing research with target users to inform and motivate design decisions that are intrinsic to the sustainability challenge;

- Engaging in self-questioning of one’s sustainability values, assumptions, and design dilemmas that impact design for sustainability.

5.2.1. Each Practice Should Be Deeply and Critically Developed

5.2.2. Practices Are Temporal and Cutting Across DT Phases

5.2.3. Interconnecting the DT Practices

6. Conclusions

- Ensuring sustainability competencies are cultivated from the early stages of DT by placing equal emphasis on activities in the problem diamond in comparison to the solution diamond.

- Embedding pedagogical scaffolding to help HE students synthesise and connect the above-listed DT practices, and thread them across the DT phases.

- Supporting the development of all values competencies, particularly critically engaging with value tensions amongst the different perspectives (e.g., within the design team, between designers and users).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Clark, R.M.; Stabryla, L.M.; Gilbertson, L.M. Sustainability coursework: Student perspectives and reflections on design thinking. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; Pisiotis, U.; Cabrera, M. GreenComp, the European Sustainability Competence Framework; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/13286 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- UNECE. Learning for the Future: Competences in Education for Sustainable Development; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://unece.org/info/Environment-Policy/Education-for-Sustainable-Development/pub/3098 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Stevenson, R.B.; Nicholls, J.; Whitehouse, H. What is Climate Change Education? Curric. Perspect. 2017, 37, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, T.; Barry, J. Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 733–739. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978008097086891081X (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; et al. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, A.; Scheffelaar, A.; Urias, E.; Zweekhorst, M.B. Training students for complex sustainability issues: A literature review on the design of inter- and transdisciplinary higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.; Bailey, I.; Warren, M.; Bissell, S. Revolutions and second-best solutions: Education for sustainable development in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2009, 34, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Manolas, E.; Pace, P. The future we want: Key issues on sustainable development in higher education after Rio and the UN decade of education for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, E.K.; de Beer, Z.L. Education for Sustainable Development in BRICS: Zoom on Higher Education; Niemczyk, E.K., de Beer, Z.L., Eds.; BRICS Education; AOSIS: Cape Town, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guaman-Quintanilla, S.; Everaert, P.; Chiluiza, K.; Valcke, M. Impact of design thinking in higher education: A multi-actor perspective on problem solving and creativity. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 33, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimur, S.; Onuki, M. Design thinking as digital transformative pedagogy in higher sustainability education: Cases from Japan and Germany. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 114, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Peng, A.; Yang, T.; Deng, S.; He, Y. A Design-Based Learning Approach for Fostering Sustainability Competency in Engineering Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Estévez, M.; Chalmeta, R. Integrating Sustainable Development Goals in educational institutions. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.M.; Kapitan, S.; Bajaj, N.; Bakonyi, A.; Sands, S. Uncovering wicked problem’s system structure: Seeing the forest for the trees. J. Soc. Mark. 2017, 7, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Sustainable Development: What You Need to Know About Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). 2024. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education/need-know (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Araneo, P. Exploring education for sustainable development (ESD) course content in higher education; a multiple case study including what students say they like. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 30, 631–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizan, S.A.; Abu Shamsi, N. Design-Based Learning as a Pedagogical Approach in an Online Learning Environment for Science Undergraduate Students. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 860097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatomo, D. Research on Education for Sustainable Development with Design-Based Research by Employing Industry 4.0 Technologies for the Issue of Single-Use Plastic Waste in Taiwan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Environmental Education for Sustainability: Defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environ. Educ. Res. 1995, 1, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencies in education for sustainable development: Exploring the student teachers’ views. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, A.; Schmidt-Keilich, M.; Muster, V.; Blazejewski, S.; Schrader, U.; Harrach, C.; Schäfer, M.; Süßbauer, E. Design thinking for sustainability: Why and how design thinking can foster sustainability-oriented innovation development. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolko, J. The divisiveness of design thinking. Interactions 2018, 25, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, B.; Trellevik, L.K.L. Sustainability-oriented innovation: Improving problem definition through combined design thinking and systems mapping approaches. Think. Skills Creat. 2021, 42, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenke, P. Higher Education Leaders as Designers. In Design in Educational Technology; Hokanson, B., Gibbons, A., Eds.; Educational Communications and Technology: Issues and Innovations; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, A.; Noweski, C.; Meinel, C. Transforming Constructivist Learning into Action: Design Thinking in Education. Des. Technol. Educ. Int. J. 2012, 17, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Beligatamulla, G.; Rieger, J.; Franz, J.; Strickfaden, M. Making Pedagogic Sense of Design Thinking in the Higher Education Context. Open Educ. Stud. 2019, 1, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luka, I. Design thinking in pedagogy: Frameworks and uses. Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 54, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, K.; Arrington, L.; Willox, L. Design Thinking: Blazing a Trail for Social and Emotional Learning in the Early Grades. Kappa Delta Pi Record 2022, 58, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design Council. The Double Diamond. 2003. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/ (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Liu, J. Visualizing the 4 Essentials of Design Thinking. 2016. Available online: https://medium.com/good-design/visualizing-the-4-essentials-of-design-thinking-17fe5c191c22 (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Brown, T.; Wyatt, J. Design Thinking for Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2010, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panke, S. Design Thinking in Education: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges. Open Education Studies. 2019, 1, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plattner, H. An Introduction to Design Thinking Process Guide. The Institute of Design at Stanford, 2010. Available online: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/ih-materials/uploads/Introduction-to-design-thinking.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Peng, F.; Altieri, B.; Hutchinson, T.; Harris, A.J.; McLean, D. Design for Social Innovation: A Systemic Design Approach in Creative Higher Education toward Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; McCarthy, J. Empathy and experience in HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’08), Florence, Italy, 5–10 April 2008; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, J.H.G.; Joyce, C.K.; Beckman, S.L. Framing innovation: Negotiating shared frames during early design phases. J. Des. Res. 2007, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskjaer, M.M.; Dalsgaard, P.; Halskov, K. Understanding Creativity Methods in Design. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Edinburgh, UK, 10–14 June 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: Edinburgh, UK, 2017; pp. 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Schmidt, M.; Lee, M.; Huang, R. Usability research in educational technology: A state-of-the-art systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 1951–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S.; Hauerwaas, A.; Helldorff, S.; Weisenfeld, U. Jamming sustainable futures: Assessing the potential of design thinking with the case study of a sustainability jam. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.H.L.; Sing Chai, C.; Wong, B.; Hong, H. Design Thinking for Education: Conceptions and Applications in Teaching and Learning; Springer Science and Business Media: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Birdman, J.; Wiek, A.; Lang, D.J. Developing key competencies in sustainability through project-based learning in graduate sustainability programs. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.; Forlizzi, J.; Evenson, S. Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 28 April–3 May 2007; ACM: San Jose, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 493–502. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1240624.1240704 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Clark, T.; Foster, L.; Sloan, L.; Bryman, A. Bryman’s Social Research Methods, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; Available online: https://bibliu.com/users/saml/samlUCL?RelayState=eyJjdXN0b21fbGF1bmNoX3VybCI6IiMvdmlldy9ib29rcy85NzgwMTkyNjM2NjE0L2VwdWIvT0VCUFMvMDAwX0FDb3Zlci5odG1sIn0%3D (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapell Hill, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tauber, P. An Exploration of the Relationships Among Connectedness to Nature, Quality of Life, and Mental Health; University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2012; Available online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1260/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Vogel, S. Thinking like a Mall: Environmental Philosophy after the End of Nature; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, Y.; Kalantari, S.; Kucirkova, N.; Vasalou, A. Exploring the Design Space for Parent-Child Reading. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2020; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3313831.3376696 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Passmore, H.A.; Martin, L.; Richardson, M.; White, M.; Hunt, A.; Pahl, S. Parental/Guardians’ Connection to Nature Better Predicts Children’s Nature Connectedness than Visits or Area-Level Characteristics. Ecopsychology 2021, 13, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.V.; Nakabayashi, M.; Hosaka, T. How to encourage parents to let children play in nature: Factors affecting parental perception of children’s nature play. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasalou, A.; Gauthier, A. The role of CCI in supporting children’s engagement with environmental sustainability at a time of climate crisis. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2023, 38, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, D.; Vallgårda, A.; Tomico, O. Embodied Design Ideation Methods: Analysing the Power of Estrangement. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’17), Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 5158–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.; Carpendale, S.; Marquardt, N.; Buxton, B. Sketching User Experiences: The Workbook, 1st ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123819598500456 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Restall, B.; Conrad, E. A literature review of connectedness to nature and its potential for environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 159, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, M.; Hunt, A.; Hinds, J.; Bragg, R.; Fido, D.; Petronzi, D.; Barbett, L.; Clitherow, T.; White, M. A Measure of Nature Connectedness for Children and Adults: Validation, Performance, and Insights. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, A. Choices for Children: Why and How to Let Students Decide. Phi Delta Kappan 1993, 75, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Amprazis, A.; Papadopoulou, P.; Malandrakis, G. Plant blindness and children’s recognition of plants as living things: A research in the primary schools context. J. Biol. Educ. 2021, 55, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P. ‘Loveable’ mammals and ‘lifeless’ plants: How children’s interest in common local organisms can be enhanced through observation of nature. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2005, 27, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K. Theorizing a child–dog encounter in the slums of La Paz using post-humanistic approaches in order to disrupt universalisms in current ‘child in nature’ debates. Child Geogr. 2016, 14, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Roedl, D.; Blevis, E.; Thomas, J. Re-conceptualizing fashion in sustainable HCI. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ’12), Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 11–15 June 2012; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 813–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halskov, K.; Hansen, N.B. The diversity of participatory design research practice at PDC 2002–2012. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | Sustainability Competences |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nature Connection | Fast Fashion |

|---|---|

| Ying (China; teacher, experience with children) | Angelina (Colombia; humanities, design skills) |

| Melanie (Indonesia; teacher, experience with children, learning design, drawing) | Stefania (Georgia; teaching) |

| Hamzah (South Korea; education) | Barack (Malawi; computer science) |

| Rihana (Saudi Arabia; education) | Sabine (Switzerland; teaching, experience with children) |

| Daksha (India; education, design skills) | Xinbei (China; no experience reported) |

| DT Phase | |

|---|---|

| Empathise/define |

|

| Ideate |

|

| Prototype |

|

| Test |

|

| Empathise/Define * | Ideate | Prototype | Test * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–4 | Week 5-Reading week | Week 6 | Week 7 | Week 8–9 | |

| Scaffolds | |||||

| Pre-defined structured Miro board | x | ||||

| Preparation sheet for planning design research and activities | x | x | x | x | |

| Reflective design thinking prompts bringing attention to insights generated, methodological reflections, and critical design decisions. | x | x | x | x | |

| Tutor and Peer Feedback | |||||

| Tutors comment on the Miro board to clarify ideas and comment on promising directions. | x | ||||

| Tutors and peers provide oral and written feedback on rotating weekly presentations reporting on design outputs and process. | x | x | x | x | x |

| Tutors and peers providing feedback during class, whilst the teams prepared their design research and activity. | x | x | x | x | |

| Nature Team | Fashion Team | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Competence | Problem Diamond | Solution Diamond | Problem Diamond | Solution Diamond |

| Values total | 11 | 11 | 5 | 2 |

| Values 1.1 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Values 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Values 1.3 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Complexity total | 12 | 12 | 9 | 0 |

| Complexity 2.1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Complexity 2.2 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Complexity 2.3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Futures total | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Futures 3.1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Futures 3.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Futures 3.3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Actions total | - | - | - | - |

| Actions 4.1 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Actions 4.2 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ |

| Actions 4.3 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

) and Fashion (

) and Fashion ( ) teams.

) teams.

) and Fashion (

) and Fashion ( ) teams.

) teams.| DT Practice | Empathise and Define | Ideate | Prototype | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability literature and children |   |  |   |  |

| User research with children driving sustainability design |   |  |  |  |

| Questioning about sustainability values and design decisions |   |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ardila Echeverry, M.P.; Gauthier, A.; Hartikainen, H.; Vasalou, A. Designing for Digital Education Futures: Design Thinking for Fostering Higher Education Students’ Sustainability Competencies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104289

Ardila Echeverry MP, Gauthier A, Hartikainen H, Vasalou A. Designing for Digital Education Futures: Design Thinking for Fostering Higher Education Students’ Sustainability Competencies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104289

Chicago/Turabian StyleArdila Echeverry, Maria Paula, Andrea Gauthier, Heidi Hartikainen, and Asimina Vasalou. 2025. "Designing for Digital Education Futures: Design Thinking for Fostering Higher Education Students’ Sustainability Competencies" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104289

APA StyleArdila Echeverry, M. P., Gauthier, A., Hartikainen, H., & Vasalou, A. (2025). Designing for Digital Education Futures: Design Thinking for Fostering Higher Education Students’ Sustainability Competencies. Sustainability, 17(10), 4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104289