A Study on the Impact of the Consumption Value of Sustainable Fashion Products on Purchase Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainable Fashion Products

2.1.1. Concept of Sustainable Fashion Products

2.1.2. Current Status of Sustainable Fashion Products in China

2.1.3. Current Status of Sustainable Fashion Products Overseas

2.1.4. Global Interaction of Digitalization and Ethical Consumption

2.2. Consumer Value

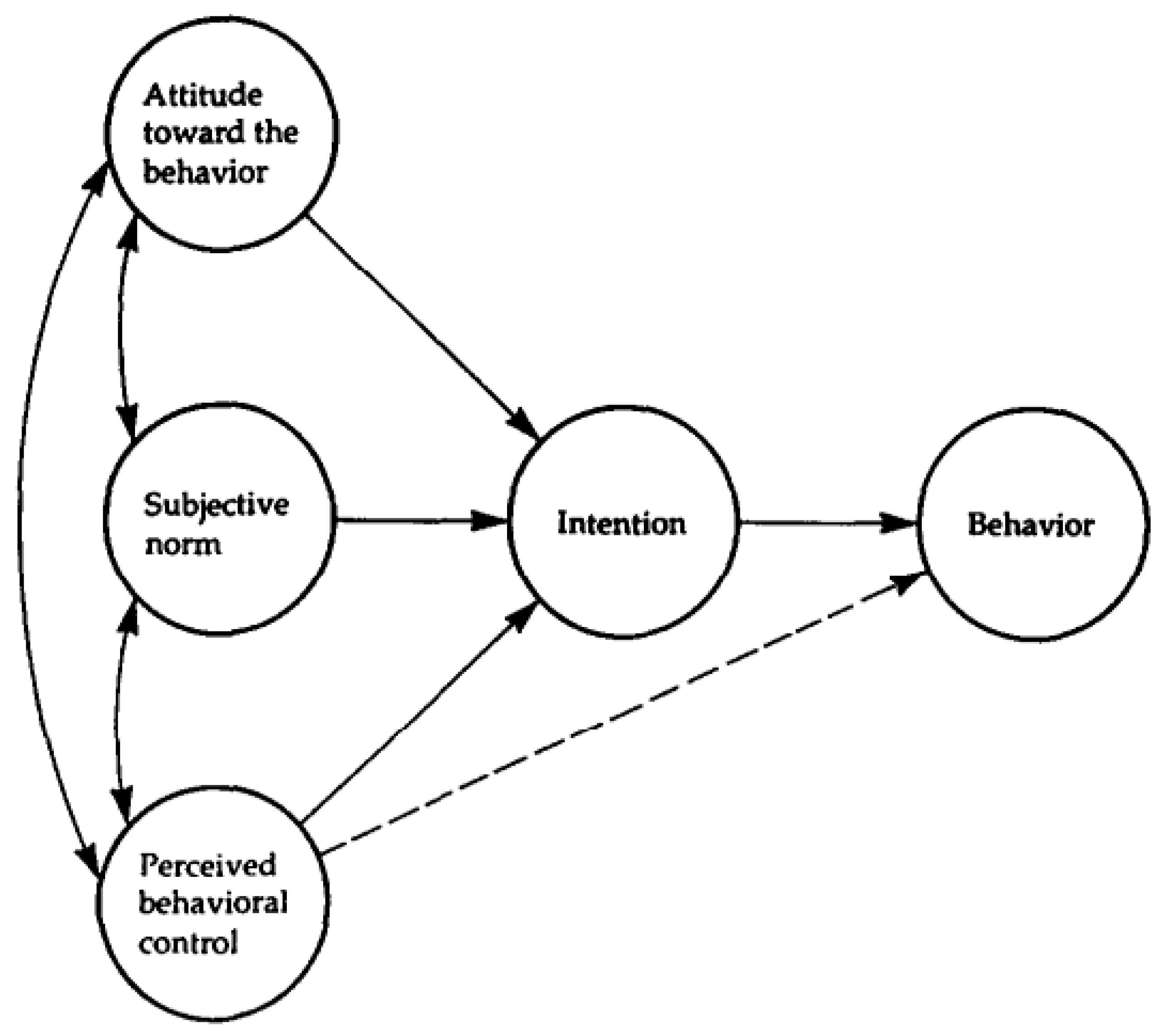

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.4. Purchase Intention

2.5. Environmental Concern

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Subjects

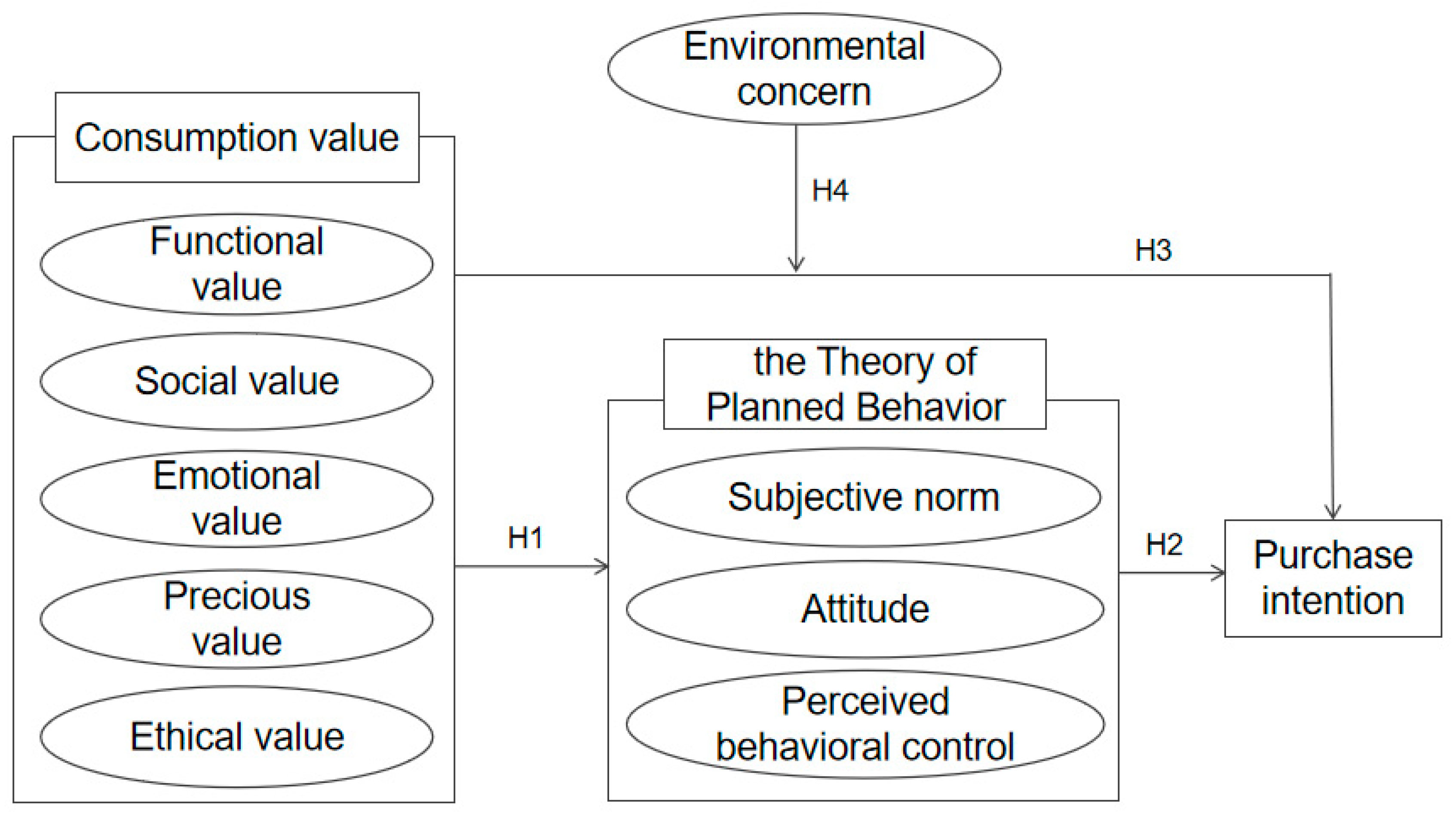

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.3. Questionnaire Design and Composition

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis Methods

4. Research Results

4.1. Analysis of Sample Characteristics

4.1.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.1.2. General Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2.1. Reliability Analysis of Measurement

4.2.2. Feasibility Analysis of Variables

- (1)

- Factor Analysis of Independent Variables

- (2)

- Factor Analysis of Parameters

- (3)

- Factor Analysis of the Dependent Variable

- (4)

- Factor Analysis of the Moderating Variable

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Discriminant Validity

4.5. Correlation Analysis

4.6. Hypothesis Testing

4.6.1. Overall Hypothesis Testing Results on the Impact of Consumer Values in China and South Korea on the Theory of Planned Behavior

4.6.2. Overall Results of Testing the Moderating Effect of Environmental Concern on Consumer Value and Purchase Intention

4.6.3. Interpretation of Analysis Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Summary and Implications

5.1.1. Research Summary

5.1.2. Discussion of Research Results

5.1.3. Implications of Research Findings

5.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baidu Baike. Is it Really Environmental Protection, or Just a New Scam? 2024. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1802364299729233307&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Gupta, V. Validating the theory of planned behavior in green purchasing behavior. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq-Machado, L.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Gómez-Prado, R.; Cuya-Velásquez, B.B.; Esquerre-Botton, S.; Morales-Ríos, F.; Almanza-Cruz, C.; Castillo-Benancio, S.; Anderson-Seminario, M.d.L.M.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; et al. Sustainable fashion and consumption patterns in peru: An environmental-attitude-intention-behavior analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Tao, Y.; Shao, M.; Yu, C. Understand the Chinese Z Generation consumers’ Green hotel visit intention: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ae-ran, K.; Jeong-soon, L. Sustainable Fashion Consumption in the Post-Corona Era. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, N.-K. Sustainable Fashion and Digital Implementation through Big Data Text Mining—Focusing on the Analysis of the Keywords ‘Sustainable + Fashion + Digital’. J. Fash. Des. 2024, 24, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay, S.; Shree, S.; Sharma, P.; Singh, A. Contribution of Nanotechnology in Shaping Sustainable Textile Design and Future Fashion Trends. In Nanotechnology—Assisted Recycling of Textile Waste: Sustainable Tools for Textiles; Springer: London, UK, 2025; pp. 207–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kook, H.S.; Kim, H.Y. A Study on Features of Sustainable Zero Waste Fashion Design; Korean Society of Basic Design & Art: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016; Volume 17, pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.-S.; Kim, J.-H. Development of Sustainable Fashion Design Prototypes from the Perspective of Clothing Composition—Focusing on Pattern Classes. Fash. Bus. 2020, 24, 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, E.-J.; Han, H.-J. A Qualitative Study on Consumer Awareness Based on Experiences of Purchasing Sustainable Fashion Products. J. Basic Des 2024, 25, 459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.-S.; Kang, Y.-H. Analysis of YouTube Content on Sustainable Jeans Fashion; Korean Society of Design Culture: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2023; Volume 29, pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sohu Finance. China’s Textile and Apparel Exports Account for over 50% of Global Share. 2017. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/210788685_313396 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- China National Textile and Apparel Council. Action Outline for Building a Modern Textile Industry System; China National Textile and Apparel Council: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Daxue Consulting. The Future of Sustainable Fashion in China. 2023. Available online: https://daxueconsulting.com/the-future-of-sustainable-fashion-in-china (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- China Fashion Network. Cases of Sustainable Fashion Brands in China. 2022. Available online: https://d.cfw.cn/news/264432-1.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Daily Economic News. Survey on Sustainable Consumption Behavior in China, NBD Economic. 2023. Available online: http://www.nbd.com.cn/rss/toutiao/articles/1425614.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Post-pandemic green consumption in China: A behavioral analysis of Gen Z. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibaba Research. Green Channel Consumption Report; Alibaba Group: Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. Digital Transformation Action Plan for the Textile Industry; MIIT Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Digital Product Passport: A Framework for Sustainable Fashion; Publications Office of the EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. Stockholm, Sweden. 1972. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/stockholm1972 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education. Tbilisi, Soviet Union. 1977. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000032022 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 1992. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Friend of the Earth. Sustainable Fashion Conference 2024: Agenda. Available online: https://friendoftheearth.org/sustainable-fashion-conference-on-february-21st-2024-agenda/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- FIT Fashion Institute of Technology. 18th Annual Sustainability Conference: Reimagining Our Future. 2024. Available online: https://impact.fitnyc.edu/2024-sustainability-conference (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Global Fashion Summit. White Paper on Fashion Industry Sustainability. 2023. Available online: http://www.doc88.com/p-38073645317759.html (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Luxe.Co. Market Forecast for Sustainable Fashion in 2024. 2023. Available online: http://news.ladymax.cn/202305/26-37622.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- McKinsey & Company. The Sustainability Paradox: Why Consumers Say One Thing but Do Another; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gucci Sustainability Report. Modular Design: A New Approach to Circular Fashion; Gucci Group: Florence, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Net Zero Roadmap for the Fashion Industry; UNEP Publications: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- So-ra, K. Analysis of Changes in Perception Regarding the Convergence of Artificial Intelligence and Fashion Using Text Mining; The Korean Society of Science & Art: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2025; Volume 43, pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Namkyung, J. Sustainable Fashion and Digital Practice through Big Data Text Mining—Key Words Analysis of ‘Sustainability+Fashion+Digital’. J. Korean Soc. Fash. Des. 2024, 24, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- LVMH & JD.com. AI-Driven Inventory Optimization: A Case Study in Sustainable Fashion; LVMH Press: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Fashion Association. K-REUSE: Revolutionizing Second-Hand Luxury in South Korea; KFA Publications: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kyung, S.Y. Analysis of Domestic Research Trends in Sustainable Fashion Using Text Mining. Hanbok Cult. 2025, 28, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithmal, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, B. Study on consumers’ purchase intentions for carbon-labeled products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindan, K.L.; Ramayah, T.; Thavanethen, M.; Raman, M.; Ilhavenil, N.; Annamalah, S.; Choong, Y.V. Modeling positive electronic word of mouth and purchase intention using theory of consumption value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-H. The Impact of Consumer Value on Attitudes Toward Eco-friendly Bakery Products, Purchase Intentions, and Willingness to Pay a Premium Price. Master’s Thesis, Dong-Eui University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Putri, F.S.; Sari, S.P. Consumption Value and Thalers’ Utility Theory: Observations on Generation Zs’ Green Purchase Intention in Indonesia. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Publ. 2023, 5, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.C.; Dong, C.M. Exploring consumers’ purchase intention on energy-efficient home appliances: Integrating the theory of planned behavior, perceived value theory, and environmental awareness. Energies 2023, 16, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo-hyun, J. A Study on the Sustainability of Consumption Based on Consumer Value and Satisfaction with Vegan Cosmetics. Master’s Thesis, Ajou University, Suwon-si, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eun-ah, L. The Impact of MZ Generation’s Consumer Value on Attitudes Toward Recycled Fiber Fashion Products, Brand Satisfaction, and Purchase Intentions: Focusing on the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). Doctoral Dissertation, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Md Hasan, S. An Empirical Study on Consumer Perceived Value of Circular Fashion. In International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings; Iowa State University Digital Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2025; Volume 81. [Google Scholar]

- Soydar, O.; Aksoy, N.C. An Examination of the Influence of Consumption Values in Shaping Online Buying Behaviour. In Dynamic Strategies for Entrepreneurial Marketing; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornikoski, E.; Maalaoui, A. Critical reflections—The Theory of Planned Behaviour: An interview with Icek Ajzen with implications for entrepreneurship research. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2019, 37, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustofa, R.H.; Kuncoro, T.G.; Atmono, D.; Hermawan, H.D. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model: The Role of Subjective Norms, Ethics, and Trust in AI Tool Adoption Among Students. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wismantoro, Y.; Susilowati, M.W.K. Do attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, and perceived control behavior matter on environmentally friendly plastic purchasing intention? Int. J. Manag. Sustain. 2025, 14, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, A. Impacts of consumer innovativeness on the intention to purchase sustainable products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Jin, B. Predictors of purchase intention toward green aarel products: A cross-cultural investigation in the USA and China. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2017, 21, 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fraguito, Â.S. Consumers’ Sustainable Fashion Consumption Intention: A Focus on Circular Fashion Practices and Slow Fashion. Master’s Thesis, Porto Faculdade De Economia Universidade, Porto, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Da-won, J.; Young-sam, K. A Study on the Factors Influencing Consumers’ Purchase Intention and Purchasing Behavior for Sustainable Fashion Products: Based on the E-TPB (Extended Theory of Planned Behavior). Fash. Bus. 2022, 26, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Manisha, G.; Ujjawal, N.U.; Sharma, S. Factor influencing purchase intension of sustainable app.arels among millennials. Sustainability 2023, 12, 1123–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, G.; Luo, X.; Tseng, H.T. Exploring generation Z consumers’ purchase intention towards green products during the COVID-19 pandemic in China, e-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering. Electron. Energy 2024, 8, 100552. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymanpor, M.; Norouzi, R. Examining the mediating role of subjective norms in the relationship between green marketing tools and green purchase intention in order to preserve the natural environment. J. Environ. Sci. Stud. 2025, 10, 9839–9852. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlen, S.; Stroude, A. Sustainable consumption, resonance, and care. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1013810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-R. The Impact of Online/Offline Word-of-Mouth Information Characteristics on Purchase Intention—Focusing on the Moderating Effects of Product Involvement and Channel Type. Master’s Thesis, Hongik University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, F.K.; Terner, A. Luxury, Fashion, and Idols-Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Examine Barriers toward Sustainable Fashion Consumption in Japan. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School, Tokyo, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chan-ho, J. The Impact of Upcycled Products on College Students’ Environmental Concern, Environmental Knowledge, and Consumption Values on Purchase Intention and Behavior: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of Residential Area. Master’s Thesis, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju-si, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eun-hye, K. A Study on the Perceived Benefits and Sacrifices of an Eco-Friendly Fashion Curation Platform on Perceived Consumer Value and Purchase Intention: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of Conspicuous Consumption Tendency. Master’s Thesis, Kookmin University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Il-jeong, Y. A Study on the Design Characteristics of Upcycling Products and Purchase Intention of Chinese Consumers: The Mediating Effect of Perceived Value. Doctoral Dissertation, Korea University, Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.-A. A Study on the Antecedents of Purchase Intention for Upcycling Fashion Products: Focusing on Environmental Values and the Theory of Planned Behavior; Korean Design Forum: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2024; Volume 29, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, M.; Liu, J.; Tan, Z. Public environmental concern, government environmental regulation and urban carbon emission reduction—Analyzing the regulating role of green finance and industrial agglomeration. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A.T. Theory of repeat purchase behavior (TRPB): A case of green hotel visitors of Bangladesh. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Singh, P.K.; Ahmad, A.; Kumar, G. Trust, convenience and environmental concern in consumer purchase intention for organic food. Span. J. Mark.—ESIC 2023, 27, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudayah, S.; Ramadhani, M.A.; Sary, K.A.; Raharjo, S.; Yudaruddin, R. Green perceived value and green product purchase intention of Gen Z consumers: Moderating role of environmental concern. Environ. Econ. 2023, 14, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Kazmi, S.Q.; Anwar, A. Impact of green marketing on green purchase intention and green consumption behavior: The moderating role of green concern. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 7, 975–993. [Google Scholar]

- Famke, S. Determinants Influencing Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Sustainable Fashion: The Moderating Roles of Green Skepticism and Environmental Concern. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Factors | Questions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Consumption Value | functional value | I-1 | Sustainable fashion products perform well. | |

| I-2 | Sustainable fashion products are durable. | |||

| I-3 | Sustainable fashion products are cost-effective. | |||

| I-4 | Sustainable fashion products are available at affordable prices. | |||

| I-5 | Sustainable fashion products are safe. | |||

| I-6 | Sustainable fashion products have a positive impact on physical health. | |||

| social value | I-7 | Sustainable fashion products are in line with my social status and taste. | ||

| I-8 | Buying sustainable fashion products can make a good impression on others. | |||

| I-9 | I think buying sustainable fashion would fit in well with group values (i.e., academic discipline, sports club, etc.). | |||

| I-10 | Buying sustainable fashion products can garner social recognition. | |||

| I-11 | Buying sustainable fashion products is a good reflection of my social identity. | |||

| I-12 | Buying sustainable fashion products increases my value. | |||

| emotional value | I-13 | Buying sustainable fashion brings me joy. | ||

| I-14 | I can achieve happiness by purchasing sustainable fashion products. | |||

| I-15 | There is satisfaction in buying sustainable fashion products. | |||

| I-16 | Buying sustainable fashion products satisfies the image I aspire to have. | |||

| I-17 | I feel good about buying sustainable fashion. | |||

| I-18 | Buying sustainable fashion makes me feel confident. | |||

| precious value | I-19 | Sustainable fashion products are what make me unique. | ||

| I-20 | Sustainable fashion products spark my curiosity. | |||

| I-21 | Sustainable fashion products are very unique in style and color. | |||

| I-22 | Sustainable fashion products can provide me with a sense of freshness. | |||

| I-23 | Buying sustainable fashion is a new experience. | |||

| ethical value | I-24 | Companies that produce sustainable fashion products refrain from exploiting labor. | ||

| I-25 | Sustainable fashion products can be ethically produced. | |||

| I-26 | The production of sustainable fashion products can address problems caused by the unfair distribution of services. | |||

| I-27 | Sustainable fashion products help improve environmental pollution. | |||

| I-28 | Sustainable fashion products can awaken corporate ethical responsibility. | |||

| I-29 | Buying sustainable fashion products can help society eliminate inequality. | |||

| II. Theory of Planned Behavior | Subjective norm | II-1 | I think most people who are important to me would support me in buying sustainable fashion. | |

| II-2 | Most people who are important to me would agree that I should buy sustainable fashion. | |||

| II-3 | Most of the people who are important to me think highly of me and influence me to buy sustainable fashion products. | |||

| II-4 | Most people who are important to me want me to buy sustainable fashion. | |||

| Attitude | II-5 | I think buying sustainable fashion is helpful. | ||

| II-6 | I think buying sustainable fashion is beneficial. | |||

| II-7 | I think it’s smart to buy sustainable fashion. | |||

| II-8 | I think buying sustainable fashion is a positive. | |||

| II-9 | I think it makes sense to buy sustainable fashion. | |||

| II-10 | I think buying sustainable fashion is a great idea. | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | II-11 | I think it’s totally my decision whether or not to buy sustainable fashion. | ||

| II-12 | I think I have complete control over the amount of sustainable fashion I want to buy. | |||

| II-13 | I think we have the resources, time, and inclination to buy sustainable fashion. | |||

| II-14 | I think I can afford to buy the sustainable fashion I need. | |||

| II-15 | I think it’s easy to buy sustainable fashion through effective channels. | |||

| III. Purchase Intention | III-1 | I intentionally buy sustainable fashion whenever possible. | ||

| III-2 | I try to buy sustainable fashion as much as possible. | |||

| III-3 | I plan to buy sustainable fashion products in the near future. | |||

| III-4 | I plan to prioritize sustainable fashion when I buy fashion products. | |||

| III-5 | I will invest more time and energy into sustainable fashion products. | |||

| IV. Environmental Concern | IV-1 | I feel like I know more about recycling than anyone else. | ||

| IV-2 | I know how to choose products and packaging that will reduce the amount of waste that goes to landfill. | |||

| IV-3 | I understand the environmental words and symbols on product packaging. | |||

| IV-4 | I understand the environmental issues of the fashion product manufacturing business, such as the impact of fashion clothing manufacturing on the environment. | |||

| V. General characteristics of sustainable fashion product purchases | V1. Through what channels do you mainly purchase sustainable fashion products? (Multiple choice) | V1-1. Online channels ① E-commerce official brand website ② Social media ③ Live streaming ④ Mobile application ⑤ Others | ||

| V1-2. Offline channels ① Brand store ② Department store ③ Market ④ Others | ||||

| V2. What are your reasons for choosing to buy your sustainable fashion products? (Multiple choice) ① Environmental protection ② Personal health ③ Personal value pursuit ④ Human care and social recognition ⑤ Good wearing feeling ⑥ Functionality and practicality ⑦ Resource recycling ⑧ Others | ||||

| V3. How interested are you in sustainable fashion products? ① Don’t care at all ② Don’t care ③ Moderate ④ Care ⑤ Very concerned | ||||

| V4. Are you willing to buy sustainable fashion products in the future? ① Willing ② Unwilling ③ I don’t know | ||||

| V5. What are the items that you purchase sustainable fashion products for? (Multiple choice) ① Clothes (tops/pants/underwear, etc.) ② Bags and similar items ③ Sundries (accessories, scarves, hats, etc.) ④ Miscellaneous items | ||||

| V6. What factors have the greatest influence on your purchasing decisions for sustainable fashion products? (Multiple choice) ① Personal concern ② Recommendations from family and friends ③ Online and mobile phone ads ④ TV and radio ads ⑤ Print ads such as magazines, newspapers, and flyers ⑥ Worn by celebrities and others ⑦ Past purchase experience ⑧ Recommendations from store staff ⑨ Others | ||||

| V7. What factors do you consider most when purchasing sustainable fashion products? (Multiple choice) ① Design (color/style) ② Material ③ Popularity ④ Quality (feeling/functionality) ⑤ Price ⑥ Brand ⑦ Others | ||||

| F. Demographic characteristics | F1. What is your gender? ① Female ② Male | |||

| F2. What year are you in? ① 1st year ② 2nd year ③ 3rd year ④ 4th year | ||||

| F3. What is your major? ① Art and Design Series ② Humanities and Social Sciences Series ③ Teacher Education Series ④ Engineering Series ⑤ Natural Science Series ⑥ Business and Economics Series ⑦ Health Care Series ⑧ Others | ||||

| F4. What is your average monthly pocket money? (Currency unit: RMB) ① Below RMB 2000 ② RMB 2000–3000 ③ RMB 3000–4000 ④ RMB 4000–5000 ⑤ More than RMB 5000 | ||||

| Item | Category | Number of People (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (1308) | China (716) | South Korea (592) | ||

| Gender | Male | 636 (48.62%) | 356 (49.72%) | 276 (46.62%) |

| Female | 672 (51.38%) | 360 (50.28%) | 316 (53.38%) | |

| Grade | 1st Year | 353 (26.99%) | 193 (26.96%) | 160 (27.03%) |

| 2nd Year | 349 (26.68%) | 186 (25.98%) | 163 (27.53%) | |

| 3rd Year | 316 (24.16%) | 177 (24.72%) | 139 (23.48%) | |

| 4th Year | 290 (22.17%) | 160 (22.35%) | 130 (21.96%) | |

| Major | Art and Design Series | 273 (20.87%) | 93 (12.99%) | 180 (30.41%) |

| Humanities and Social Sciences Series | 215 (16.44%) | 101 (14.11%) | 114 (19.26%) | |

| Teacher Training Series | 122 (9.33%) | 119 (16.62%) | 3 (0.51%) | |

| Engineering Series | 242 (18.5%) | 142 (19.83%) | 100 (16.89%) | |

| Natural Sciences Series | 81 (6.19%) | 74 (10.34%) | 7 (1.18%) | |

| Business and Economics Series | 118 (9.02%) | 104 (14.53%) | 14 (2.36%) | |

| Health Series | 215 (16.44%) | 67 (9.36%) | 148 (25.00%) | |

| Other | 42 (3.21%) | 16 (2.23%) | 26 (4.39%) | |

| Average Monthly Pocket Money | Below RMB 2000 | 378 (28.9%) | 191 (26.68%) | 187 (31.59%) |

| RMB 2000–3000 | 403 (30.81%) | 208 (29.05%) | 195 (32.94%) | |

| RMB 3000–4000 | 274 (20.95%) | 155 (21.65%) | 119 (20.10%) | |

| RMB 4000–5000 | 135 (10.32%) | 102 (14.25%) | 33 (5.57%) | |

| Above RMB 5000 | 118 (9.02%) | 60 (8.38%) | 58 (9.80%) | |

| Item | Category | Number of People (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | China | South Korea | |||

| Where do you mainly purchase fashion products | Online Channels | Official Brand Websites | 819 (62.61%) | 456 (63.69%) | 363 (61.32%) |

| Social Media | 515 (39.37%) | 396 (55.31%) | 119 (20.1%) | ||

| Live Streaming | 222 (16.97%) | 197 (27.51%) | 25 (4.22%) | ||

| Mobile Applications | 631 (48.24%) | 374 (52.23%) | 257 (43.41%) | ||

| Others | 95 (7.26%) | 57 (7.96%) | 38 (6.42%) | ||

| Offline Channels | Brand Specialty Stores | 836 (63.91%) | 463 (64.66%) | 373 (63.01%) | |

| Department Stores | 606 (46.33%) | 376 (52.51%) | 230 (38.85%) | ||

| Markets | 215 (16.44%) | 166 (23.18%) | 49 (8.28%) | ||

| Others | 134 (10.24%) | 70 (9.78%) | 64 (10.81%) | ||

| Reasons for purchasing sustainable fashion products | Environmental Protection | 630 (48.17%) | 437 (61.03%) | 193 (32.6%) | |

| Personal Health | 345 (26.38%) | 270 (37.71%) | 75 (12.67%) | ||

| Pursuit of Personal Values | 368 (28.13%) | 173 (24.16%) | 195 (32.94%) | ||

| Human Care and Social Recognition | 171 (13.07%) | 117 (16.34%) | 54 (9.12%) | ||

| Good Wearing Feeling | 251 (19.19%) | 146 (20.39%) | 105 (17.74%) | ||

| Functionality and Practicality | 509 (38.91%) | 299 (41.76%) | 210 (35.47%) | ||

| Resource Reuse | 488 (37.31%) | 394 (55.03%) | 94 (15.88%) | ||

| Others | 66 (5.05%) | 50 (6.98%) | 16 (2.7%) | ||

| Interest in sustainable fashion products | Indifferent | 74 (5.66%) | 42 (5.87%) | 32 (5.41%) | |

| Unconcerned | 169 (12.92%) | 76 (10.61%) | 93 (15.71%) | ||

| Average | 341 (26.07%) | 101 (14.11%) | 240 (40.54%) | ||

| Concerned | 531 (40.6%) | 361 (50.42%) | 170 (28.72%) | ||

| Very Concerned | 193 (14.76%) | 136 (18.99%) | 57 (9.63%) | ||

| Willingness to purchase sustainable fashion products | Willing | 864 (66.06%) | 503 (70.25%) | 361 (60.98%) | |

| Unwilling | 110 (8.41%) | 96 (13.41%) | 14 (2.36%) | ||

| Don’t Know | 334 (25.54%) | 117 (16.34%) | 217 (36.66%) | ||

| Categories of purchased sustainable fashion products | Clothing (tops/pants/underwear, etc.) | 912 (69.72%) | 479 (66.9%) | 433 (73.14%) | |

| Baggage Goods | 464 (35.47%) | 304 (42.46%) | 160 (27.03%) | ||

| Sundries (accessories, scarves, hats, etc.) | 489 (37.39%) | 377 (52.65%) | 112 (18.92%) | ||

| Others | 124 (9.48%) | 93 (12.99%) | 31 (5.24%) | ||

| Most influential factors in purchasing decisions | Personal Attention | 793 (60.63%) | 435 (60.75%) | 358 (60.47%) | |

| Family and Friends’ Recommendations | 335 (25.61%) | 198 (27.65%) | 137 (23.14%) | ||

| Online and Mobile Advertising | 468 (35.78%) | 295 (41.2%) | 173 (29.22%) | ||

| Television Advertising | 375 (28.67%) | 354 (49.44%) | 21 (3.55%) | ||

| Print Advertising (magazines, newspapers, flyers, etc.) | 376 (28.75%) | 344 (48.04%) | 32 (5.41%) | ||

| Celebrity and Others’ Wearing | 461 (35.24%) | 392 (54.75%) | 69 (11.66%) | ||

| Past Purchase Experience | 472 (36.09%) | 413 (57.68%) | 59 (9.97%) | ||

| Sales Staff’s Recommendations | 202 (15.44%) | 186 (25.98%) | 16 (2.7%) | ||

| Others | 67 (5.12%) | 32 (4.47%) | 35 (5.91%) | ||

| Most important factors when purchasing sustainable fashion products | Design (color/style) | 858 (65.60%) | 493 (68.85%) | 365 (61.66%) | |

| Material | 540 (41.28%) | 395 (55.17%) | 145 (24.49%) | ||

| Fashion | 486 (37.16%) | 410 (57.26%) | 76 (12.84%) | ||

| Quality (wear comfort/functionality) | 542 (41.44%) | 361 (50.42%) | 181 (30.57%) | ||

| Price | 416 (31.8%) | 289 (40.36%) | 127 (21.45%) | ||

| Brand | 371 (28.36%) | 311 (43.44%) | 60 (10.14%) | ||

| Others | 58 (4.43%) | 43 (6.01%) | 15 (2.53%) | ||

| Factors | Measurement Variables | Number of Items | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption value | Functional value | 6 | 0.964 |

| Social value | 6 | 0.960 | |

| Emotional value | 6 | 0.955 | |

| Precious value | 5 | 0.971 | |

| Ethical value | 6 | 0.963 | |

| Theory of Planned Behavior | Subjective norms | 4 | 0.972 |

| Attitude | 6 | 0.956 | |

| Perceived behavioral control | 5 | 0.937 | |

| Purchase intention | Purchase intention | 5 | 0.957 |

| Environmental concern | Environmental concern | 4 | 0.976 |

| Item | Factor | Communality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Value | Ethical Value | Social Value | Emotional Value | Precious Value | ||

| I-1 | 0.966 | 0.054 | 0.103 | 0.034 | 0.071 | 0.953 |

| I-2 | 0.936 | 0.067 | 0.105 | 0.038 | 0.075 | 0.899 |

| I-3 | 0.871 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.038 | 0.068 | 0.769 |

| I-4 | 0.912 | 0.040 | 0.077 | 0.009 | 0.058 | 0.843 |

| I-5 | 0.873 | 0.027 | 0.132 | 0.041 | 0.044 | 0.784 |

| I-6 | 0.931 | 0.054 | 0.103 | 0.026 | 0.061 | 0.885 |

| I-7 | 0.109 | 0.061 | 0.920 | 0.084 | 0.072 | 0.874 |

| I-8 | 0.095 | 0.053 | 0.926 | 0.068 | 0.063 | 0.878 |

| I-9 | 0.085 | 0.055 | 0.877 | 0.053 | 0.080 | 0.789 |

| I-10 | 0.095 | 0.053 | 0.911 | 0.092 | 0.062 | 0.854 |

| I-11 | 0.075 | 0.068 | 0.868 | 0.094 | 0.065 | 0.777 |

| I-12 | 0.117 | 0.061 | 0.919 | 0.094 | 0.085 | 0.878 |

| I-13 | 0.016 | 0.090 | 0.095 | 0.923 | 0.101 | 0.880 |

| I-14 | 0.054 | 0.087 | 0.077 | 0.905 | 0.094 | 0.844 |

| I-15 | 0.041 | 0.083 | 0.064 | 0.851 | 0.103 | 0.747 |

| I-16 | 0.012 | 0.092 | 0.082 | 0.888 | 0.091 | 0.812 |

| I-17 | 0.011 | 0.067 | 0.081 | 0.860 | 0.087 | 0.758 |

| I-18 | 0.054 | 0.112 | 0.080 | 0.931 | 0.111 | 0.901 |

| I-19 | 0.077 | 0.104 | 0.086 | 0.126 | 0.966 | 0.973 |

| I-20 | 0.073 | 0.088 | 0.084 | 0.125 | 0.957 | 0.952 |

| I-21 | 0.052 | 0.091 | 0.080 | 0.114 | 0.883 | 0.810 |

| I-22 | 0.076 | 0.094 | 0.093 | 0.119 | 0.958 | 0.955 |

| I-23 | 0.090 | 0.108 | 0.071 | 0.092 | 0.892 | 0.829 |

| I-24 | 0.048 | 0.919 | 0.069 | 0.079 | 0.087 | 0.865 |

| I-25 | 0.055 | 0.926 | 0.055 | 0.098 | 0.072 | 0.878 |

| I-26 | 0.035 | 0.857 | 0.055 | 0.081 | 0.096 | 0.754 |

| I-27 | 0.034 | 0.933 | 0.069 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.891 |

| I-28 | 0.068 | 0.872 | 0.046 | 0.081 | 0.081 | 0.780 |

| I-29 | 0.035 | 0.955 | 0.058 | 0.098 | 0.086 | 0.934 |

| Eigenvalues | 5.135 | 5.109 | 5.054 | 4.953 | 4.495 | — |

| Percentage % | 17.709 | 17.618 | 17.429 | 17.079 | 15.501 | — |

| Cumulative Percentage % | 17.709 | 35.326 | 52.755 | 69.835 | 85.336 | — |

| KMO | 0.934 | |||||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate Chi-Square | 49,853.289 | ||||

| Degrees of Freedom | 406 | |||||

| Significance | 0.000 | |||||

| Item | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Perceived Behavioral Control | Subjective Norm | Communality | |

| II-1 | 0.095 | 0.082 | 0.978 | 0.972 |

| II-2 | 0.098 | 0.063 | 0.971 | 0.956 |

| II-3 | 0.076 | 0.061 | 0.906 | 0.830 |

| II-4 | 0.094 | 0.070 | 0.969 | 0.953 |

| II-5 | 0.892 | 0.115 | 0.104 | 0.820 |

| II-6 | 0.911 | 0.108 | 0.074 | 0.847 |

| II-7 | 0.860 | 0.097 | 0.050 | 0.752 |

| II-8 | 0.910 | 0.091 | 0.070 | 0.841 |

| II-9 | 0.870 | 0.119 | 0.084 | 0.778 |

| II-10 | 0.956 | 0.112 | 0.080 | 0.933 |

| II-11 | 0.123 | 0.908 | 0.072 | 0.845 |

| II-12 | 0.111 | 0.901 | 0.046 | 0.826 |

| II-13 | 0.099 | 0.838 | 0.059 | 0.716 |

| II-14 | 0.091 | 0.923 | 0.068 | 0.865 |

| II-15 | 0.128 | 0.868 | 0.053 | 0.773 |

| Eigenvalues | 4.958 | 4.033 | 3.715 | — |

| Percentage % | 33.055 | 26.884 | 24.767 | — |

| Cumulative Percentage % | 33.055 | 59.939 | 84.706 | — |

| KMO | 0.912 | |||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate Chi-Square | 23,996.000 | ||

| Degrees of Freedom | 105 | |||

| Significance | 0.000 | |||

| Item | Factor | Communality |

|---|---|---|

| Purchase Intention | ||

| III-1 | 0.954 | 0.910 |

| III-2 | 0.946 | 0.895 |

| III-3 | 0.881 | 0.776 |

| III-4 | 0.968 | 0.937 |

| III-5 | 0.889 | 0.790 |

| Eigenvalues | 4.307 | — |

| Percentage % | 86.136 | — |

| Cumulative Percentage % | 86.136 | — |

| KMO | 0.909 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate Chi-Square | 8082.670 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 10 | |

| Significance | 0.000 | |

| Item | Factor | Communality |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Concern | ||

| IV-1 | 0.988 | 0.976 |

| IV-2 | 0.984 | 0.968 |

| IV-3 | 0.919 | 0.845 |

| IV-4 | 0.982 | 0.964 |

| Eigenvalues | 3.753 | — |

| Percentage % | 93.821 | — |

| Cumulative Percentage % | 93.821 | — |

| KMO | 0.864 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate Chi-Square | 10,333.795 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 6 | |

| Significance | 0.000 | |

| Scale | Dimension | Item | Path Coefficient | Standardized Path Coefficient | C.R. | AVE | CR | Fit Indices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption value | Functional value | I-1 | 1 | 0.988 | — | 0.827 | 0.966 | CMIN/DF = 1.846, GFI = 0.966, AGFI = 0.960, NFI = 0.987, CFI = 0.994, RMR = 0.011, RMSEA = 0.025, IFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.993 |

| I-2 | 0.897 | 0.935 | 86.250 *** | |||||

| I-3 | 0.620 | 0.844 | 54.410 *** | |||||

| I-4 | 0.858 | 0.897 | 68.630 *** | |||||

| I-5 | 0.628 | 0.847 | 55.243 *** | |||||

| I-6 | 0.898 | 0.938 | 87.644 *** | |||||

| Social value | 1–7 | 1 | 0.928 | — | 0.810 | 0.962 | ||

| I-8 | 0.930 | 0.927 | 61.574 *** | |||||

| I-9 | 0.685 | 0.857 | 48.779 *** | |||||

| I-10 | 0.916 | 0.909 | 57.786 *** | |||||

| I-11 | 0.671 | 0.846 | 47.260 *** | |||||

| I-12 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 62.265 *** | |||||

| Emotional value | I-13 | 1 | 0.932 | — | 0.790 | 0.957 | ||

| I-14 | 0.920 | 0.901 | 56.707 *** | |||||

| I-15 | 0.656 | 0.828 | 45.185 *** | |||||

| I-16 | 0.902 | 0.883 | 53.477 *** | |||||

| I-17 | 0.654 | 0.833 | 45.882 *** | |||||

| I-18 | 0.960 | 0.948 | 67.760 *** | |||||

| Precious value | I-19 | 1 | 0.997 | — | 0.882 | 0.974 | ||

| I-20 | 0.907 | 0.977 | 155.188 *** | |||||

| I-21 | 0.630 | 0.857 | 59.372 *** | |||||

| I-22 | 0.930 | 0.981 | 168.508 *** | |||||

| I-23 | 0.648 | 0.874 | 64.248 *** | |||||

| Ethical value | I-24 | 1 | 0.916 | — | 0.822 | 0.965 | ||

| I-25 | 0.958 | 0.930 | 60.240 *** | |||||

| I-26 | 0.680 | 0.829 | 44.346 *** | |||||

| I-27 | 0.974 | 0.935 | 61.248 *** | |||||

| I-28 | 0.677 | 0.847 | 46.579 *** | |||||

| I-29 | 0.987 | 0.973 | 70.811 *** | |||||

| Theory of Planned Behavior | Subjective norms | II-1 | 1 | 0.992 | 0.907 | 0.975 | CMIN/DF = 2.510, GFI = 0.978, AGFI = 0.970, NFI = 0.991, CFI = 0.995, RMR = 0.010, RMSEA = 0.034, IFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.993 | |

| II-2 | 0.911 | 0.977 | 141.910 *** | |||||

| II-3 | 0.653 | 0.858 | 58.624 *** | |||||

| II-4 | 0.909 | 0.977 | 142.102 *** | |||||

| Attitude | II-5 | 1 | 0.887 | 0.795 | 0.959 | |||

| II-6 | 0.926 | 0.902 | 50.348 *** | |||||

| II-7 | 0.692 | 0.828 | 41.676 *** | |||||

| II-8 | 0.922 | 0.902 | 50.238 *** | |||||

| II-9 | 0.685 | 0.848 | 43.742 *** | |||||

| II-10 | 0.994 | 0.976 | 62.019 *** | |||||

| Perceived behavioral control | II-11 | 1 | 0.902 | 0.758 | 0.940 | |||

| II-12 | 0.908 | 0.889 | 48.948 *** | |||||

| II-13 | 0.673 | 0.789 | 38.112 *** | |||||

| II-14 | 0.947 | 0.924 | 53.802 *** | |||||

| II-15 | 0.692 | 0.842 | 43.305 *** | |||||

| Purchase intention | Purchase intention | III-1 | 1 | 0.949 | 0.830 | 0.960 | CMIN/DF = 4.541, GFI = 0.993, AGFI = 0.980, NFI = 0.997, CFI = 0.998, RMR = 0.004, RMSEA = 0.052, IFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.996, | |

| III-2 | 0.912 | 0.938 | 71.253 *** | |||||

| III-3 | 0.631 | 0.832 | 47.763 *** | |||||

| III-4 | 0.935 | 0.976 | 86.519 *** | |||||

| III-5 | 0.662 | 0.850 | 50.535 *** | |||||

| Environmental concern | Environmental concern | IV-1 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.921 | 0.979 | CMIN/DF = 1.576, GFI = 0.999, AGFI = 0.994, NFI = 1.000, CFI = 1.000, RMR = 0.001, RMSEA = 0.021, IFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000 | |

| IV-2 | 0.927 | 0.986 | 182.679 *** | |||||

| IV-3 | 0.632 | 0.866 | 61.674 *** | |||||

| IV-4 | 0.925 | 0.984 | 173.345 *** |

| IA | IB | IC | ID | IE | IIA | IIB | IIC | III | IV | |

| IA | 0.924 | |||||||||

| IB | 0.218 | 0.917 | ||||||||

| IC | 0.089 | 0.192 | 0.907 | |||||||

| ID | 0.162 | 0.187 | 0.246 | 0.95 | ||||||

| IE | 0.115 | 0.146 | 0.209 | 0.21 | 0.922 | |||||

| IIA | 0.153 | 0.283 | 0.202 | 0.195 | 0.231 | 0.963 | ||||

| IIB | 0.248 | 0.23 | 0.276 | 0.261 | 0.266 | 0.186 | 0.91 | |||

| IIC | 0.311 | 0.272 | 0.275 | 0.296 | 0.237 | 0.149 | 0.244 | 0.897 | ||

| III | 0.445 | 0.504 | 0.418 | 0.442 | 0.457 | 0.343 | 0.387 | 0.389 | 0.928 | |

| IV | 0.599 | 0.537 | 0.524 | 0.534 | 0.511 | 0.281 | 0.366 | 0.435 | 0.718 | 0.969 |

| IA | IB | IC | ID | IE | IIA | IIB | IIC | III | IV | |

| IA | ||||||||||

| IB | 0.225 | |||||||||

| IC | 0.092 | 0.2 | ||||||||

| ID | 0.167 | 0.193 | 0.254 | |||||||

| IE | 0.118 | 0.152 | 0.217 | 0.217 | ||||||

| IIA | 0.157 | 0.293 | 0.209 | 0.199 | 0.237 | |||||

| IIB | 0.258 | 0.24 | 0.287 | 0.27 | 0.276 | 0.192 | ||||

| IIC | 0.325 | 0.285 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.249 | 0.155 | 0.257 | |||

| III | 0.461 | 0.524 | 0.436 | 0.456 | 0.474 | 0.355 | 0.402 | 0.407 | ||

| IV | 0.616 | 0.554 | 0.541 | 0.547 | 0.527 | 0.287 | 0.378 | 0.453 | 0.74 |

| IA | IB | IC | ID | IE | IIA | IIB | IIC | III | IV | |

| I-1 | 0.977 | 0.215 | 0.089 | 0.163 | 0.117 | 0.154 | 0.244 | 0.314 | 0.438 | 0.593 |

| I-2 | 0.949 | 0.215 | 0.094 | 0.166 | 0.128 | 0.148 | 0.23 | 0.294 | 0.437 | 0.587 |

| I-3 | 0.874 | 0.157 | 0.082 | 0.146 | 0.091 | 0.127 | 0.224 | 0.277 | 0.379 | 0.504 |

| I-4 | 0.917 | 0.18 | 0.059 | 0.14 | 0.095 | 0.13 | 0.214 | 0.277 | 0.396 | 0.54 |

| I-5 | 0.884 | 0.228 | 0.089 | 0.131 | 0.087 | 0.137 | 0.226 | 0.278 | 0.401 | 0.518 |

| I-6 | 0.941 | 0.21 | 0.079 | 0.15 | 0.113 | 0.151 | 0.236 | 0.284 | 0.413 | 0.575 |

| I-7 | 0.214 | 0.936 | 0.182 | 0.176 | 0.139 | 0.262 | 0.214 | 0.268 | 0.472 | 0.513 |

| I-8 | 0.199 | 0.936 | 0.164 | 0.164 | 0.129 | 0.259 | 0.205 | 0.248 | 0.477 | 0.489 |

| I-9 | 0.186 | 0.887 | 0.148 | 0.173 | 0.127 | 0.243 | 0.206 | 0.218 | 0.432 | 0.468 |

| I-10 | 0.199 | 0.924 | 0.186 | 0.164 | 0.129 | 0.268 | 0.213 | 0.254 | 0.465 | 0.492 |

| I-11 | 0.176 | 0.881 | 0.185 | 0.164 | 0.141 | 0.255 | 0.199 | 0.224 | 0.446 | 0.476 |

| I-12 | 0.222 | 0.937 | 0.192 | 0.189 | 0.141 | 0.273 | 0.23 | 0.281 | 0.482 | 0.515 |

| I-13 | 0.068 | 0.19 | 0.938 | 0.23 | 0.193 | 0.204 | 0.267 | 0.251 | 0.391 | 0.488 |

| I-14 | 0.101 | 0.174 | 0.919 | 0.222 | 0.189 | 0.164 | 0.249 | 0.244 | 0.381 | 0.49 |

| I-15 | 0.085 | 0.157 | 0.865 | 0.221 | 0.179 | 0.175 | 0.234 | 0.259 | 0.361 | 0.451 |

| I-16 | 0.062 | 0.174 | 0.901 | 0.215 | 0.19 | 0.188 | 0.242 | 0.229 | 0.378 | 0.473 |

| I-17 | 0.058 | 0.168 | 0.868 | 0.205 | 0.164 | 0.173 | 0.234 | 0.231 | 0.352 | 0.429 |

| I-18 | 0.105 | 0.183 | 0.95 | 0.244 | 0.217 | 0.195 | 0.272 | 0.279 | 0.412 | 0.517 |

| I-19 | 0.161 | 0.186 | 0.249 | 0.987 | 0.211 | 0.198 | 0.266 | 0.292 | 0.438 | 0.531 |

| I-20 | 0.154 | 0.181 | 0.245 | 0.975 | 0.194 | 0.182 | 0.246 | 0.287 | 0.432 | 0.517 |

| I-21 | 0.129 | 0.168 | 0.225 | 0.899 | 0.188 | 0.181 | 0.226 | 0.277 | 0.399 | 0.472 |

| I-22 | 0.159 | 0.19 | 0.241 | 0.977 | 0.2 | 0.194 | 0.257 | 0.289 | 0.43 | 0.524 |

| I-23 | 0.165 | 0.164 | 0.208 | 0.911 | 0.205 | 0.169 | 0.244 | 0.261 | 0.4 | 0.49 |

| I-24 | 0.109 | 0.146 | 0.186 | 0.199 | 0.93 | 0.236 | 0.24 | 0.221 | 0.439 | 0.475 |

| I-25 | 0.115 | 0.133 | 0.201 | 0.187 | 0.936 | 0.222 | 0.255 | 0.233 | 0.434 | 0.48 |

| I-26 | 0.093 | 0.127 | 0.181 | 0.198 | 0.869 | 0.181 | 0.235 | 0.212 | 0.388 | 0.447 |

| I-27 | 0.096 | 0.145 | 0.2 | 0.189 | 0.943 | 0.223 | 0.253 | 0.193 | 0.418 | 0.479 |

| I-28 | 0.123 | 0.122 | 0.181 | 0.188 | 0.884 | 0.192 | 0.228 | 0.213 | 0.407 | 0.463 |

| I-29 | 0.098 | 0.137 | 0.205 | 0.202 | 0.966 | 0.221 | 0.259 | 0.238 | 0.442 | 0.484 |

| II-1 | 0.168 | 0.278 | 0.206 | 0.207 | 0.241 | 0.986 | 0.187 | 0.158 | 0.348 | 0.294 |

| II-2 | 0.133 | 0.283 | 0.196 | 0.188 | 0.23 | 0.978 | 0.187 | 0.14 | 0.326 | 0.264 |

| II-3 | 0.145 | 0.247 | 0.17 | 0.173 | 0.18 | 0.911 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.313 | 0.252 |

| II-4 | 0.142 | 0.282 | 0.204 | 0.181 | 0.236 | 0.976 | 0.183 | 0.145 | 0.334 | 0.27 |

| II-5 | 0.224 | 0.212 | 0.264 | 0.247 | 0.246 | 0.194 | 0.906 | 0.229 | 0.352 | 0.344 |

| II-6 | 0.228 | 0.212 | 0.255 | 0.243 | 0.259 | 0.167 | 0.921 | 0.224 | 0.374 | 0.341 |

| II-7 | 0.227 | 0.203 | 0.222 | 0.214 | 0.196 | 0.139 | 0.866 | 0.205 | 0.325 | 0.315 |

| II-8 | 0.212 | 0.206 | 0.268 | 0.233 | 0.247 | 0.162 | 0.916 | 0.207 | 0.341 | 0.328 |

| II-9 | 0.223 | 0.202 | 0.224 | 0.229 | 0.239 | 0.174 | 0.882 | 0.23 | 0.341 | 0.319 |

| II-10 | 0.237 | 0.222 | 0.267 | 0.258 | 0.261 | 0.177 | 0.965 | 0.234 | 0.376 | 0.349 |

| II-11 | 0.304 | 0.263 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.223 | 0.148 | 0.234 | 0.922 | 0.379 | 0.42 |

| II-12 | 0.286 | 0.249 | 0.255 | 0.254 | 0.217 | 0.122 | 0.22 | 0.91 | 0.343 | 0.404 |

| II-13 | 0.224 | 0.23 | 0.246 | 0.241 | 0.204 | 0.128 | 0.202 | 0.841 | 0.305 | 0.346 |

| II-14 | 0.293 | 0.251 | 0.246 | 0.284 | 0.218 | 0.142 | 0.205 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 0.407 |

| II-15 | 0.281 | 0.225 | 0.246 | 0.267 | 0.2 | 0.128 | 0.232 | 0.878 | 0.342 | 0.37 |

| III-1 | 0.44 | 0.487 | 0.414 | 0.439 | 0.449 | 0.325 | 0.373 | 0.382 | 0.955 | 0.71 |

| III-2 | 0.428 | 0.481 | 0.389 | 0.422 | 0.424 | 0.325 | 0.374 | 0.365 | 0.946 | 0.676 |

| III-3 | 0.369 | 0.434 | 0.354 | 0.352 | 0.374 | 0.296 | 0.303 | 0.308 | 0.877 | 0.592 |

| III-4 | 0.437 | 0.502 | 0.411 | 0.443 | 0.455 | 0.342 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.968 | 0.708 |

| III-5 | 0.383 | 0.431 | 0.369 | 0.387 | 0.415 | 0.302 | 0.347 | 0.351 | 0.89 | 0.636 |

| IV-1 | 0.592 | 0.528 | 0.511 | 0.516 | 0.497 | 0.279 | 0.357 | 0.422 | 0.706 | 0.987 |

| IV-2 | 0.583 | 0.515 | 0.51 | 0.509 | 0.497 | 0.266 | 0.359 | 0.418 | 0.706 | 0.983 |

| IV-3 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.503 | 0.536 | 0.494 | 0.274 | 0.348 | 0.43 | 0.661 | 0.921 |

| IV-4 | 0.586 | 0.529 | 0.507 | 0.506 | 0.493 | 0.269 | 0.353 | 0.417 | 0.706 | 0.981 |

| Functional Value | Social Value | Emotional Value | Precious Value | Ethical Value | Subjective Norms | Attitude | Perceived Behavioral Control | Purchase Intention | Environmental Concern | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional value | 1 | |||||||||

| Social value | 0.218 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Emotional value | 0.088 ** | 0.193 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Precious value | 0.162 *** | 0.187 *** | 0.246 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Ethical value | 0.114 *** | 0.146 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.209 *** | 1 | |||||

| Subjective norms | 0.153 *** | 0.284 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.233 *** | 1 | ||||

| Attitude | 0.247 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.277 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.266 *** | 0.187 *** | 1 | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.311 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.237 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.243 *** | 1 | ||

| Purchase intention | 0.445 *** | 0.505 *** | 0.419 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.458 *** | 0.343 *** | 0.387 *** | 0.389 *** | 1 | |

| Environmental concern | 0.599 *** | 0.536 *** | 0.523 *** | 0.531 *** | 0.509 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.434 *** | 0.718 *** | 1 |

| Hypothesis Result | Estimate | S.E. | Standardized Estimate | C.R. | p | Remarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H1-1 | Functional value | → | Subjective norms | 0.062 | 0.023 | 0.074 | 2.772 | 0.006 | Established |

| H1-2 | Social value | → | Subjective norms | 0.210 | 0.026 | 0.217 | 8.066 | *** | Established | |

| H1-3 | Emotional value | → | Subjective norms | 0.105 | 0.026 | 0.108 | 4.033 | *** | Established | |

| H1-4 | Precious value | → | Subjective norms | 0.085 | 0.023 | 0.096 | 3.626 | *** | Established | |

| H1-5 | Ethical value | → | Subjective norms | 0.160 | 0.025 | 0.169 | 6.303 | *** | Established | |

| H1-6 | Functional value | → | Attitude | 0.135 | 0.021 | 0.172 | 6.454 | *** | Established | |

| H1-7 | Social value | → | Attitude | 0.106 | 0.024 | 0.118 | 4.392 | *** | Established | |

| H1-8 | Emotional value | → | Attitude | 0.166 | 0.024 | 0.184 | 6.832 | *** | Established | |

| H1-9 | Precious value | → | Attitude | 0.124 | 0.022 | 0.150 | 5.696 | *** | Established | |

| H1-10 | Ethical value | → | Attitude | 0.159 | 0.024 | 0.180 | 6.727 | *** | Established | |

| H1-11 | Functional value | → | Perceived behavioral control | 0.187 | 0.020 | 0.250 | 9.377 | *** | Established | |

| H1-12 | Social value | → | Perceived behavioral control | 0.138 | 0.023 | 0.161 | 6.019 | *** | Established | |

| H1-13 | Emotional value | → | Perceived behavioral control | 0.147 | 0.023 | 0.171 | 6.376 | *** | Established | |

| H1-14 | Precious value | → | Perceived behavioral control | 0.141 | 0.021 | 0.179 | 6.781 | *** | Established | |

| H1-15 | Ethical value | → | Perceived behavioral control | 0.113 | 0.022 | 0.134 | 5.044 | *** | Established | |

| CMIN/DF = 2.006, GFI = 0.940, AGFI = 0.933, NFI = 0.976, CFI = 0.988, RMR = 0.094, RMSEA = 0.028, IFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.987 | ||||||||||

| H2 | H2-1 | Subjective norms | → | Purchase intention | 0.246 | 0.023 | 0.266 | 10.802 | *** | Established |

| H2-2 | Attitude | → | Purchase intention | 0.291 | 0.025 | 0.296 | 11.750 | *** | Established | |

| H2-3 | Perceived behavioral control | → | Purchase intention | 0.325 | 0.026 | 0.318 | 12.476 | *** | Established | |

| CMIN/DF = 2.821, GFI = 0.964, AGFI = 0.955, NFI = 0.986, CFI = 0.991, RMR = 0.086, RMSEA = 0.037, IFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.989 | ||||||||||

| H3 | H3-1 | Functional value | → | Purchase intention | 0.248 | 0.015 | 0.340 | 16.475 | *** | Established |

| H3-2 | Social value | → | Purchase intention | 0.319 | 0.018 | 0.382 | 18.020 | *** | Established | |

| H3-3 | Emotional value | → | Purchase intention | 0.215 | 0.017 | 0.257 | 12.361 | *** | Established | |

| H3-4 | Precious value | → | Purchase intention | 0.203 | 0.016 | 0.265 | 13.012 | *** | Established | |

| H3-5 | Ethical value | → | Purchase intention | 0.279 | 0.017 | 0.340 | 16.180 | *** | Established | |

| CMIN/DF = 2.348, GFI = 0.945, AGFI = 0.937, NFI = 0.979, CFI = 0.988, RMR = 0.122,RMSEA = 0.032, IFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.987 | ||||||||||

| Model | Variable | B | se | t | p | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4-1 | Constant | 3.101 | 0.017 | 181.103 | 0.000 | Established |

| Functional value | 0.033 | 0.021 | 1.618 | 0.106 | ||

| Environmental concern | 0.577 | 0.019 | 29.739 | 0.000 | ||

| Functional value × Environmental concern | 0.085 | 0.017 | 4.913 | 0.000 | ||

| H4-2 | Constant | 3.112 | 0.016 | 191.013 | 0.000 | Established |

| Social value | 0.150 | 0.021 | 7.221 | 0.000 | ||

| Environmental concern | 0.522 | 0.018 | 28.625 | 0.000 | ||

| Social value × Environmental concern | 0.077 | 0.018 | 4.273 | 0.000 | ||

| H4-3 | Constant | 3.103 | 0.017 | 187.730 | 0.000 | Established |

| Emotional value | 0.044 | 0.021 | 2.096 | 0.036 | ||

| Environmental concern | 0.573 | 0.018 | 31.273 | 0.000 | ||

| Emotional value × Environmental concern | 0.102 | 0.019 | 5.373 | 0.000 | ||

| H4-4 | Constant | 3.097 | 0.016 | 190.319 | 0.000 | Established |

| Precious value | 0.078 | 0.020 | 3.903 | 0.000 | ||

| Environmental concern | 0.564 | 0.018 | 30.830 | 0.000 | ||

| Precious value × Environmental concern | 0.110 | 0.017 | 6.425 | 0.000 | ||

| H4-5 | Constant | 3.124 | 0.016 | 191.157 | 0.000 | Established |

| Ethical value | 0.109 | 0.020 | 5.503 | 0.000 | ||

| Environmental concern | 0.539 | 0.018 | 29.815 | 0.000 | ||

| Ethical value × Environmental concern | 0.049 | 0.018 | 2.799 | 0.005 |

| Hypothesis | Validation Result | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior (subjective norms, attitudes, perceived behavioral control). | Accepted |

| H1-1 | The functional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior subjective norms. | Accepted |

| H1-2 | The social value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior subjective norms. | Accepted |

| H1-3 | The emotional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior subjective norms. | Accepted |

| H1-4 | The precious value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior subjective norms. | Accepted |

| H1-5 | The ethical value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior subjective norms. | Accepted |

| H1-6 | The functional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior attitudes. | Accepted |

| H1-7 | The social value of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior attitudes. | Accepted |

| H1-8 | The emotional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior attitudes. | Accepted |

| H1-9 | The precious value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior attitudes. | Accepted |

| H1-10 | The ethical value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior attitudes. | Accepted |

| H1-11 | The functional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior perceived behavioral control. | Accepted |

| H1-12 | The social value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior perceived behavioral control. | Accepted |

| H1-13 | The emotional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior perceived behavioral control. | Accepted |

| H1-14 | The precious value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior perceived behavioral control. | Accepted |

| H1-15 | The ethical value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on consumers’ planned behavior perceived behavioral control. | Accepted |

| H2 | Consumers’ planned behavior (subjective norms, attitudes, perceived behavioral control) will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H2-1 | The subjective norms of consumers’ planned behavior will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H2-2 | The attitudes of consumers’ planned behavior will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H2-3 | The perceived behavioral control of consumers’ planned behavior will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H3 | Consumer value will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H3-1 | The functional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H3-2 | The social value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H3-3 | The emotional value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H3-4 | The precious value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H3-5 | The ethical value dimension of consumer value will have a positive impact on the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. | Accepted |

| H4 | Environmental concern will play a positive moderating role between consumer value and purchase intention. | Accepted |

| H4-1 | Environmental concern will play a positive moderating role between the functional value dimension of consumer value and purchase intention. | Accepted |

| H4-2 | Environmental concern will play a positive moderating role between the social value dimension of consumer value and purchase intention. | Accepted |

| H4-3 | Environmental concern will play a positive moderating role between the emotional value dimension of consumer value and purchase intention. | Accepted |

| H4-4 | Environmental concern will play a positive moderating role between the precious value dimension of consumer value and purchase intention. | Accepted |

| H4-5 | Environmental concern will play a positive moderating role between the ethical value dimension of consumer value and purchase intention. | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Lee, Y.-S. A Study on the Impact of the Consumption Value of Sustainable Fashion Products on Purchase Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104278

Wu Y, Lee Y-S. A Study on the Impact of the Consumption Value of Sustainable Fashion Products on Purchase Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104278

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yifei, and Young-Sook Lee. 2025. "A Study on the Impact of the Consumption Value of Sustainable Fashion Products on Purchase Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104278

APA StyleWu, Y., & Lee, Y.-S. (2025). A Study on the Impact of the Consumption Value of Sustainable Fashion Products on Purchase Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability, 17(10), 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104278