1. Introduction

The relationship between the tourism industry and income inequality is complex and can vary depending on factors such as the type of tourism, the level of economic development in a region, and how wealth is distributed among the population [

1]. Tourism can help mitigate income inequality by creating jobs and reducing poverty, particularly when lower-income groups engage in tourism-related activities, thereby increasing their earning potential [

2,

3,

4]. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council [

5], the tourism industry contributed to global employment by creating 27 million new jobs by the end of 2023, accounting for 9.1% of global economic growth and promoting inclusive development. However, tourism can also have negative impacts, such as the displacement of local communities, unequal distribution of benefits, and the prevalence of seasonal, low-wage employment [

6].

Tourism can drive urban renewal and rural development, helping to reduce regional disparities by allowing communities to grow economically in their places of origin. It also serves as an effective tool for developing countries to engage with the global economy. Tourism contributes to a country’s GDP, employment, and foreign currency earnings [

7] and can stimulate growth in related sectors such as transportation, lodging, and food production. Additionally, tourism can lessen a country’s reliance on a single industry by generating revenue from external sources. The extent of the tourism sector’s contribution to economic growth is determined by factors such as investment in infrastructure and human capital, the quality of tourism products and services, and the efficacy of sectoral policies and regulations [

8,

9]. Furthermore, tourism can provide direct support to the poor through financial benefits, employment opportunities, and community development initiatives [

10,

11]. Currently, tourism is seen as a strategy for economic development, contributing to income growth, utilizing human capital, and enhancing the standard of living in local communities [

12]. When well-planned and effectively managed, the tourism industry can stimulate economic growth and boost government tax revenues in host countries. Reflecting this potential, the tourism sector experienced a remarkable growth rate of 22% from 2021 to 2022 [

13]. According to the United Nations 2030 Agenda, involving local populations and all key stakeholders in tourism development can make tourism an effective tool for community development and reducing inequalities.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—which include Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—have long been recognized for their abundance of natural resources [

14]. In recent years, however, these countries have acknowledged the need to diversify their economies and reduce dependence on oil [

15]. As a result, tourism development projects have become important for economic growth in some GCC countries, as tourism generates revenue, creates jobs, and promotes cultural exchange [

16]. Several factors contribute to the growing importance of the tourism industry in the GCC region, including economic diversification, investment in infrastructure, hospitality, entertainment, and employment [

17]. Additionally, tourism fosters global understanding, builds cultural bridges, and promotes infrastructure development and environmental conservation [

18]. Despite these positive contributions, the negative impacts of tourism cannot be overlooked. Unregulated visitor numbers can place significant pressure on natural ecosystems, leading to problems such as soil erosion, pollution, habitat loss, and rising living costs [

19,

20]. Furthermore, increased greenhouse gas emissions from tourist transport contribute to climate change, which can have far-reaching consequences for both wildlife and human communities. Socially, while tourism can promote intercultural exchange, it may also lead to the erosion of cultural identity within local communities [

21]. These challenges highlight the need for responsible tourism management to ensure sustainable development.

While environmental and sociocultural concerns highlight the unsustainable dimensions of tourism growth, another critical issue tied to tourism development is its effect on income inequality.

The issue of equality has become a central topic in both international and domestic discourse, as governments and organizations seek solutions to growing economic and social disparities. According to Raza and Shah [

22], increasing income inequality is one of the causes of economic crises. Beyond concerns related to fairness and social justice, there are significant economic and political motivations for addressing inequality in all its dimensions, given its far-reaching effects on societal development [

23]. From an economic perspective, high levels of income inequality slow economic growth [

24]. Economic equality is crucial in societies, but its relevance and influence depend on ideological, cultural, and religious contexts [

8,

25,

26,

27]. Rising inequality has notable consequences for both economic growth and macroeconomic stability [

24], including its capacity to concentrate political and decision-making power among a few individuals, bring about misallocation of human resources, cause political and economic instability, reduce investment, and increase the likelihood of economic and financial crises.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a larger effect on income distribution than the other pandemics [

28,

29]. As a result, it drew attention to rising income inequality, which has become a significant concern. Long-term and heightened levels of inequality, particularly those related to unequal opportunities, can have significant societal costs. For example, persistent income inequality can substantially impact individuals’ educational and vocational decisions [

30]. Moreover, when income inequality is driven by rent-seeking behavior rather than merit or productivity, it undermines incentives for innovation and economic growth. Under such circumstances, individuals may prioritize obtaining preferential treatment and protection, leading to the misallocation of resources, corruption, and favoritism. These dynamics can have detrimental effects on both the economy and society. Notably, a loss of public trust in institutions may occur, gradually eroding social cohesion and diminishing optimism about the future [

31].

The GCC, formed in 1981, consists of six member states: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain. The governance structure of these states is predominantly monarchical, either in the form of absolute monarchies or constitutional monarchies, where the ruling families hold substantial power. Each state executes its government unique to its historical and cultural context; however, they share common elements, such as a strong central authority and limited political pluralism. This system often encompasses a Supreme Council, consisting of the monarchs of each state, which convenes for collective decision-making and cooperation on regional issues. The GCC also features a Ministerial Council and a Secretariat General to facilitate ongoing collaboration and policy execution [

32].

Over the past decade, GCC countries have increasingly relied on tourism to diversify their oil-dependent economies. Governments have launched ambitious national strategies to develop tourism infrastructure, attract international visitors, and position tourism as a key pillar of sustainable growth. While these initiatives have stimulated sectoral expansion, the distributive effects of tourism—particularly on income inequality—remain underexplored. In particular, GCC countries have prioritized tourism development in response to rising unemployment rates among their national populations, viewing tourism as a potential solution to this pressing issue [

18]. Importantly, in nondemocratic systems, such as those found in the GCC, where decision-making is highly centralized, the role of the state in shaping tourism outcomes and managing inequality is especially pronounced. Political structures may influence whether tourism revenues are redistributed equitably or concentrated in elite-dominated sectors. This study addresses this gap by empirically examining the relationship between tourism development and income distribution in the GCC, using education expenditure as a proxy for income equality.

The present study evaluates the issue of income inequality by examining the impact of tourism on income equality in GCC countries, applying the Kuznets curve framework to quarterly data from 2014Q1 to 2023Q4, based on data availability. The Kuznets curve theory posits that as an economy grows, income inequality initially increases and then decreases after reaching a certain level of economic growth. This inverted U-shaped relationship implies that inequality may rise in the early stages of economic development but will eventually decline as the economy matures and wealth distribution becomes more equitable. By applying this theory to GCC countries, the present study aims to analyze how tourism has influenced income equality in these nations over the specified period.

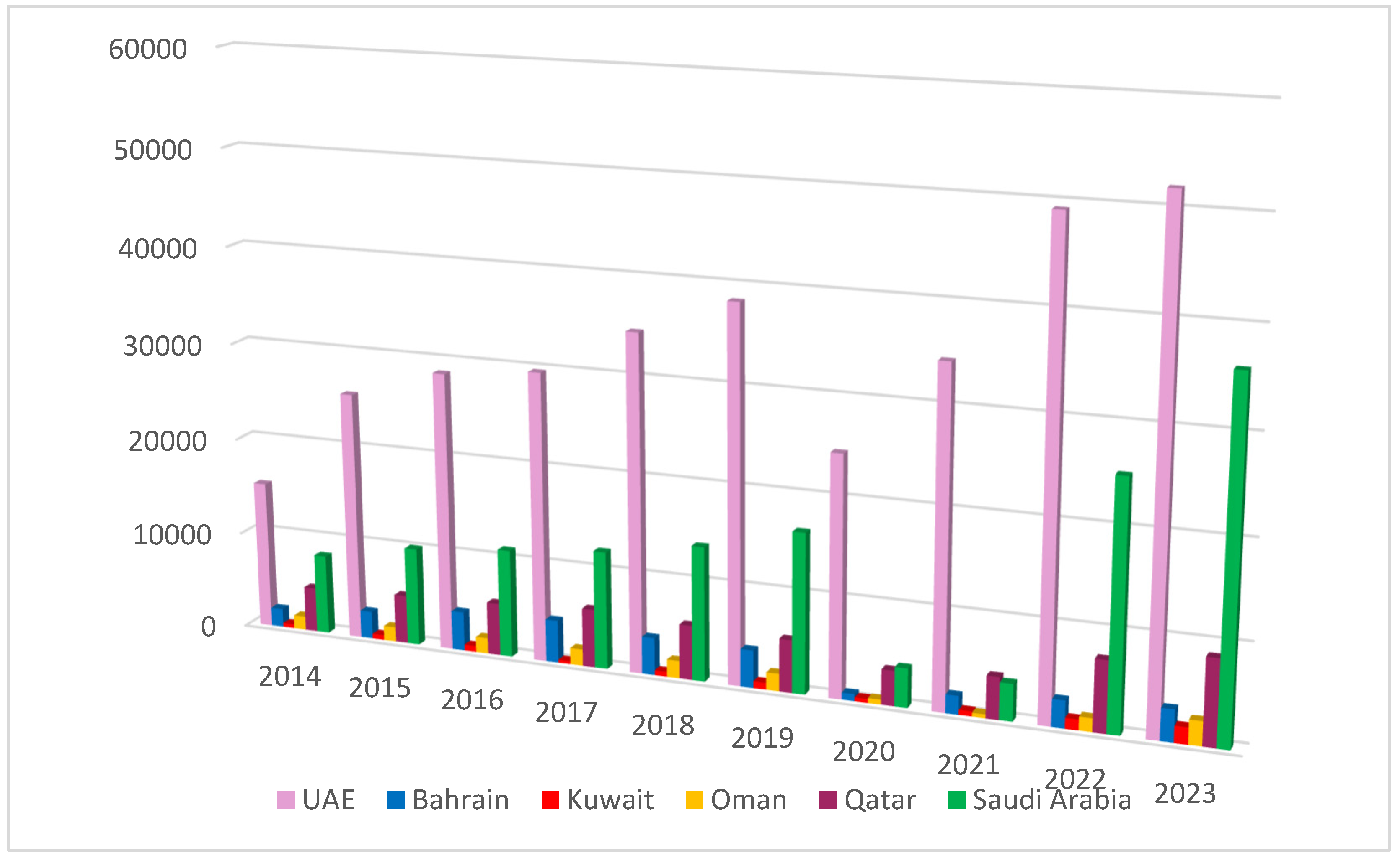

Figure 1 compares the tourism revenues of the six GCC countries from 2014 to 2023 The United Arab Emirates leads the region in tourism revenue, followed by Saudi Arabia and Qatar. The United Arab Emirates recorded its highest tourism revenue in 2019, reaching USD 38 billion, while Saudi Arabia followed with USD 19 billion in the same year. A notable decline in tourism revenues occurred in 2020, likely due to the global pandemic’s impact on the tourism sector.

An important variable that reflects income equality is education expenditure per capita.

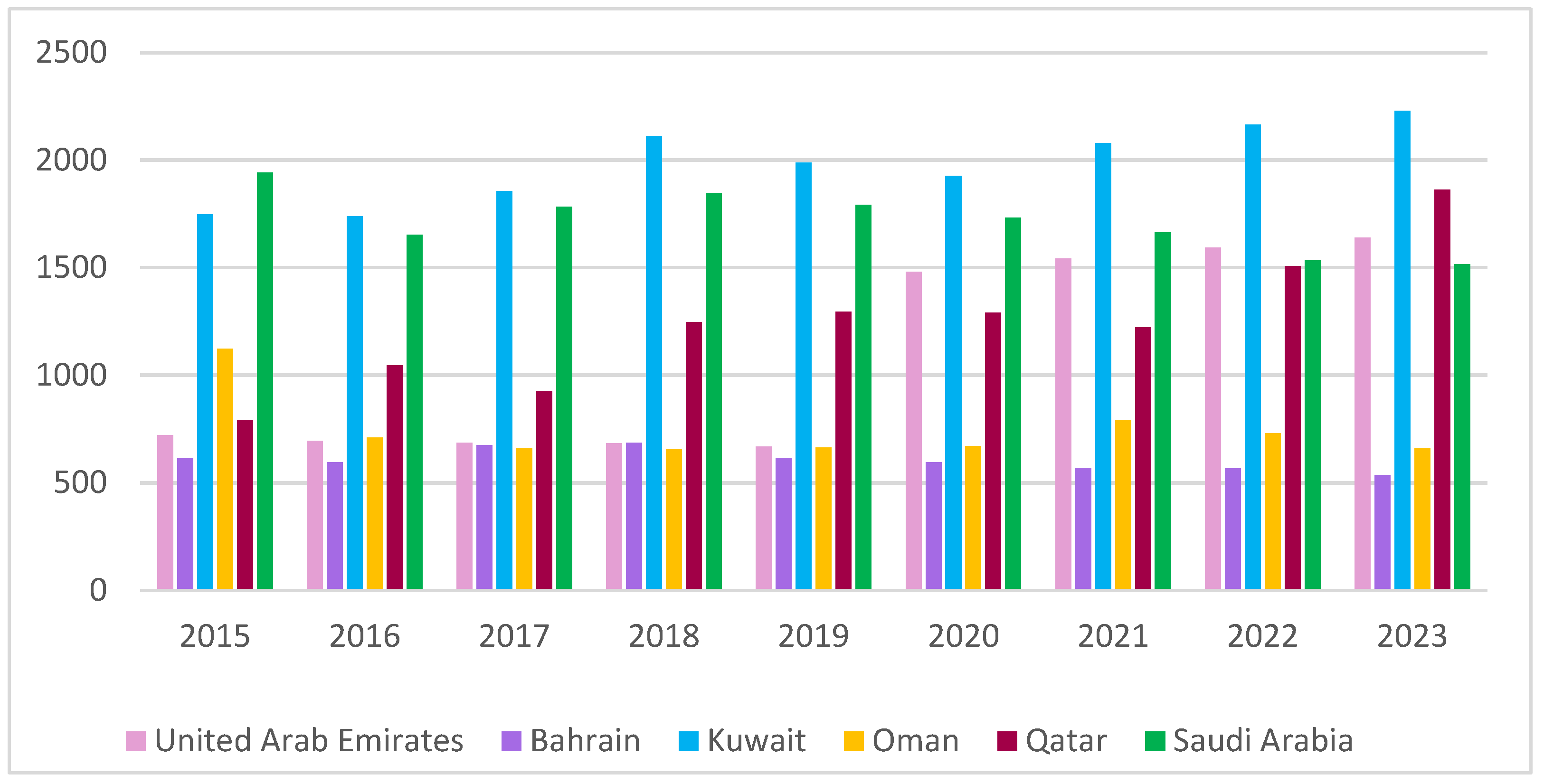

Figure 2 presents the differences in education spending among the studied GCC countries. Saudi Arabia had the highest education spending per capita in 2015, at around USD 1700 per capita. On average, spending on education among the studied GCC countries is approximately USD 1200 per capita.

From 2015 to 2023, Kuwait consistently recorded the highest levels of education expenditure per capita, surpassing USD 2000 in 2023. For Kuwait, the dataset includes both education and training expenditure, as both categories reflect investments in education. This adjustment has improved the measurement of per capita education expenditure compared to the previous data version. Saudi Arabia, while leading in 2015, experienced relatively stable spending levels with a slight upward trend, reaching around USD 1800 in 2023. In contrast, Oman and Bahrain maintained the lowest levels of education expenditure throughout the period, remaining below USD 800 per capita. Qatar showed a steady and significant increase in education spending, particularly after 2019, rising to nearly USD 1800 by 2023, indicating enhanced investment in human capital. The United Arab Emirates also saw a gradual increase, overtaking Saudi Arabia in some years, particularly from 2020 onward. Bahrain’s expenditure remained relatively flat across the entire period, suggesting limited change in fiscal prioritization for education.

These differences highlight the variation in policy emphasis and fiscal capacity across the GCC, with countries like Kuwait and Qatar demonstrating stronger commitments to public education investment. Such disparities may have implications for long-term income equality outcomes and labor market preparedness in the region.

Moreover, the students enrolled in public education accounted for 18.6% of the total GCC population in 2022/2023, underlining the growing importance of education in the region [

1].

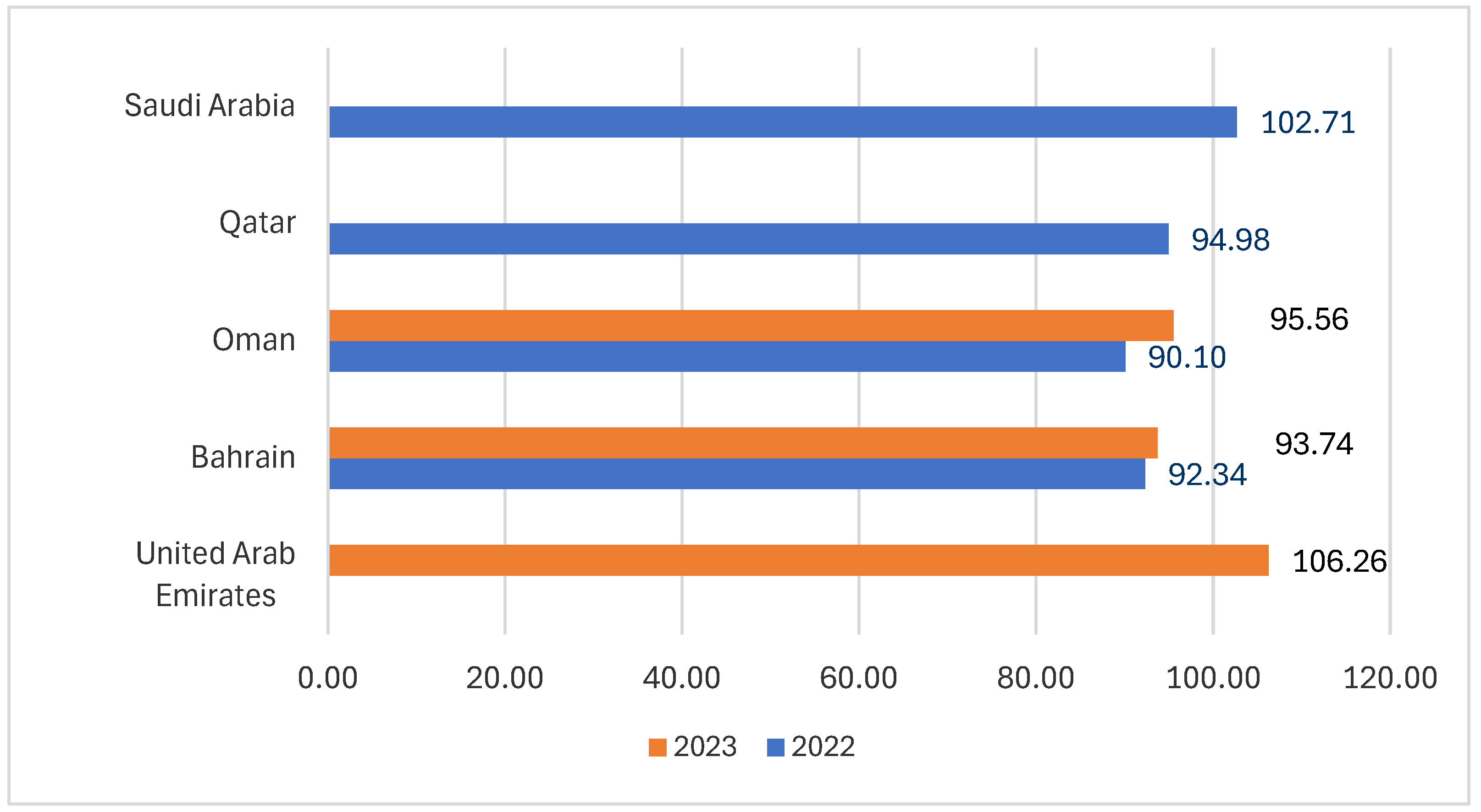

Figure 3 presents the gross enrollment rates in primary education across selected GCC countries, using the most recent available data for each country—2022 or 2023.

The United Arab Emirates recorded the highest rate at 106.26% in 2023, exceeding 100%. Saudi Arabia followed with 102.71% in 2022, indicating similarly strong educational coverage. Oman and Bahrain showed moderate improvements, with Oman rising from 90.10% in 2022 to 95.56% in 2023, while Bahrain increased slightly from 92.34% to 93.74%. Qatar, which only reported data for 2022, had a rate of 94.98%. Despite the variation in reporting years, the data reflects generally high levels of access to primary education across the region, though performance differs between countries. In terms of student distribution between public and private education institutions, the total number of students in public education across the GCC reached 10.7 million in the 2022/2023 academic year, up from 9.8 million in 2017/2018.

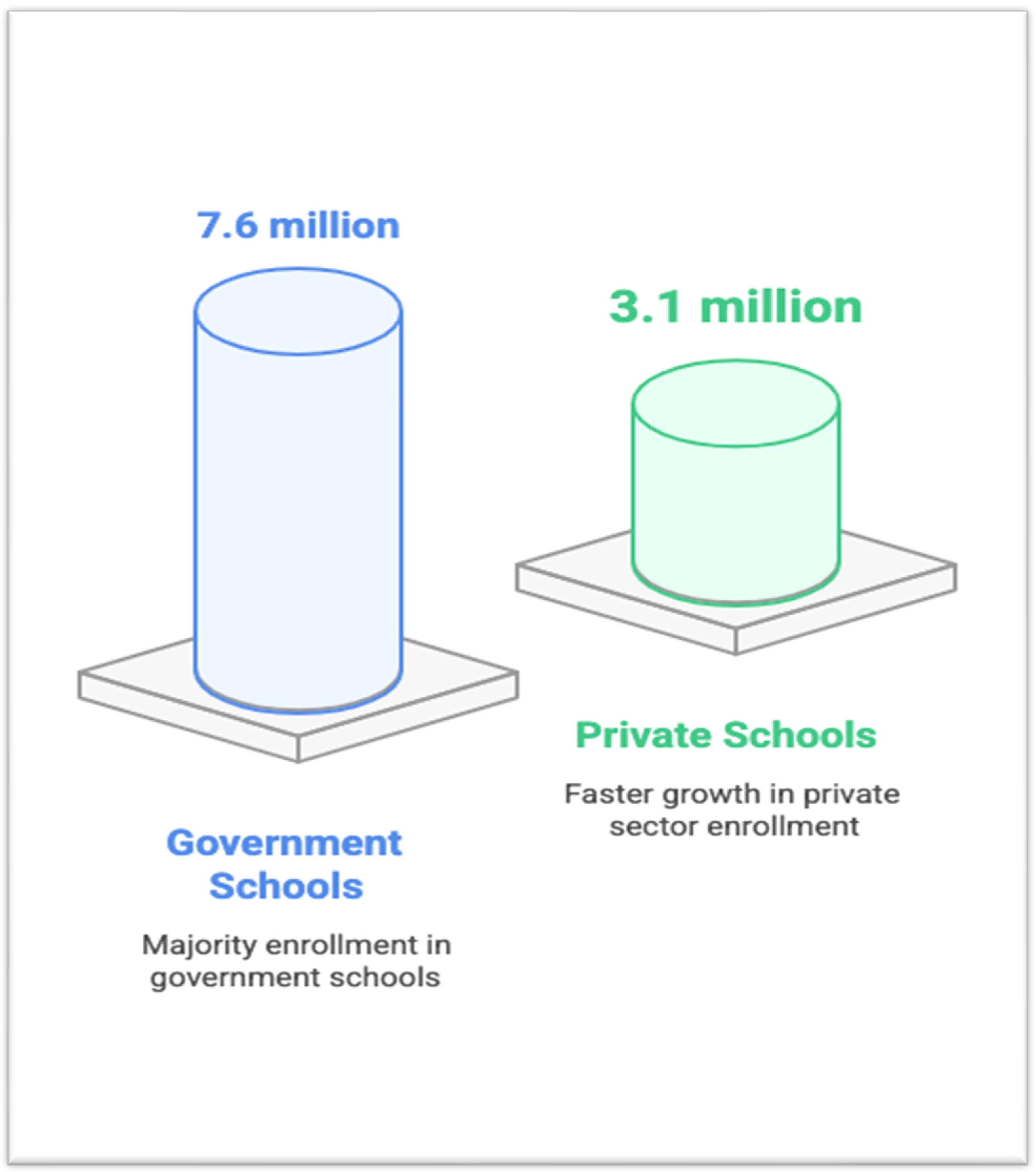

Figure 4 shows an average annual growth rate of 0.7% for public education over this period. In contrast, the number of students in private education reached approximately 3.1 million, with an average annual growth rate of 5% during the same period [

1].

These data suggest that student enrollment is growing quicker in the private sector than in the public sector. The majority of students in the GCC will remain enrolled in government institutions, accounting for 70.9% of all students in 2022–2023.

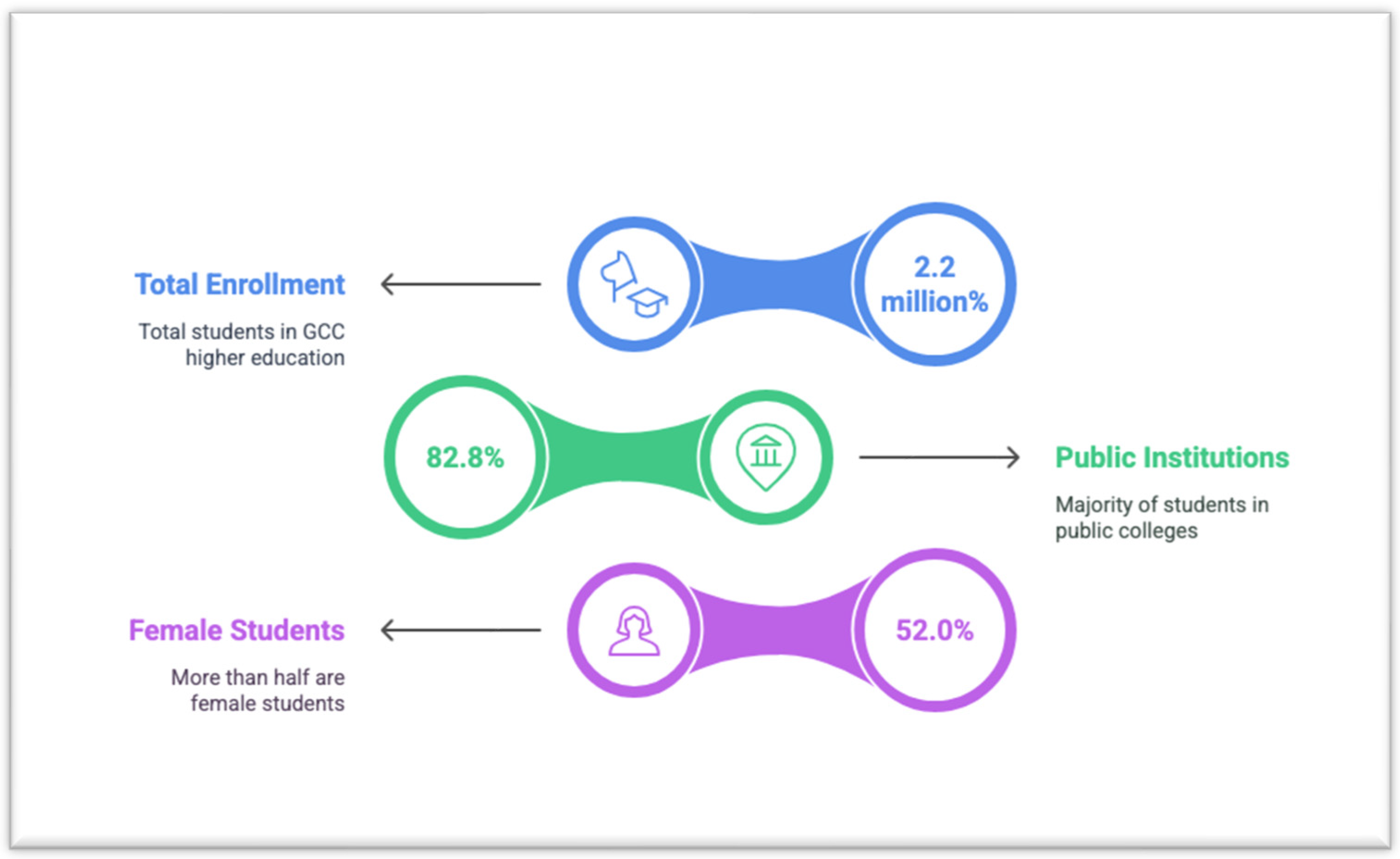

Beyond primary and secondary education, the GCC region has also witnessed steady growth in higher education enrollment. As shown in

Figure 5, higher education institutions in the GCC enrolled 2.2 million students in the academic year 2022/2023, rising from 2.0 million students in 2017/2018, reflecting an average annual growth rate of 2.4% over this period. Public institutions enrolled the majority of students and accounted for 82.8% of total enrollment in 2022/2023, while the rest attended private institutions or pursued their studies abroad. Additionally, female students comprised 52.0% of the total enrollment in higher education across the GCC in the same year.

This study will test the existence of the Kuznets hypothesis, as no prior research has specifically tested this hypothesis in the context of the studied GCC countries. This paper uniquely addresses the role of tourism in mitigating income inequality, suggesting that in the early stages of tourism development, the tourism industry may increase income inequality in GCC countries. However, after a certain level of development, increased tourism revenue could reduce income inequality among these countries’ communities. Due to the lack of direct income inequality measurements in GCC nations, education expenditure is employed as a proxy in this study.

Education spending is widely acknowledged as a critical factor in achieving social and economic justice, as increased investment in education improves access to opportunities, reduces income gaps, and promotes long-term economic mobility. In the absence of standard income inequality metrics such as the Gini coefficient or income distribution data, education spending provides a trustworthy alternative, evidence of the government’s attempts to create inclusive growth and equal opportunity. This strategy is consistent with the current literature linking higher education expenditure to increased income equality, making it a viable alternative to direct inequality measures in the GCC context. This paper is structured as follows: First, a review of the relevant literature is presented. Next, the data and methodology used in the analysis are described. The subsequent section discusses the empirical results, and, finally, the paper concludes with a summary of the key findings and implications

3. Materials and Methods

To evaluate the link between tourism development and income equality in GCC countries from 2014Q1 to 2020Q4 using panel data, the present study uses education expenditure as a proxy for income equality, following the methods of other scholars [

67,

68]. Additionally, other factors such as foreign direct investment (FDI), trade openness, and income are considered to potentially account for this relationship [

35,

37,

69]. To evaluate the existence of the Kuznets curve, the square of the tourism revenue variable is used to estimate the impact of tourism revenue on income equality [

70].

In the given model, t denotes time, and i represents the studied countries, which include the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. This model illustrates the relationship between tourism and income inequality according to the Kuznets curve theory. This theory posits that in the early stages of tourism development, income inequality increases due to a lack of skilled individuals and the fact that most workers are not sufficiently educated. As these workers improve their skills, they enter the market and secure jobs, leading to a decline in income inequality during the second stage of development. This progression represents the inverse U-shaped relationship predicted by the Kuznets curve theory. The present study uses expenditure on education as a proxy for income equality because public education spending can help lower income inequality by offering equal learning opportunities, thereby distributing human capital and income more fairly and increasing income equality [

38,

50,

52].

Table 1 outlines the variables of the present study.

The dependent variable is education expenditure, which serves as a proxy for income equality [

52,

71]. An increase in education expenditure indicates a decline in income inequality, and vice versa. The independent variables include tourism revenue (TOU), the squared term of tourism revenue (

) in current US dollars, the number of international tourist arrivals (TRAV), government effectiveness (GI), and FDI.

This study uses data from multiple official sources. Tourism revenue and the governance index were obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. Education expenditure was sourced from the ministries of finance in the respective GCC countries. FDI data were collected from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The number of international tourist arrivals was obtained from the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). All variables were transformed into natural logarithms, except for the governance index. It remains in its original scale because it is a bonded, composite score that does not follow a ratio scale, making logarithmic transformation inappropriate.

In empirical economic and financial research, panel data techniques provide a powerful framework for examining dynamic relationships across both cross-sectional and time series dimensions. This study utilizes a cross-sectionally augmented autoregressive distributed lag (CS-ARDL) model to investigate the underlying relationships within the dataset. This approach helps account for unobserved heterogeneity, dynamic adjustments, and long-run equilibrium relationships, ensuring a thorough and reliable econometric analysis.

A panel ARDL model is used to capture both short-run dynamics and long-run relationships within the panel structure, making it especially relevant for macroeconomic and financial studies, where variables may be nonstationary but cointegrated over time [

72]. Lastly, the CS-ARDL model is applied to address cross-sectional dependence (CSD), which is a crucial factor when working with panel data involving globally or regionally interconnected entities [

73].

By incorporating these methodologies, this study ensures robust empirical analysis while effectively addressing heterogeneity, endogeneity, and dynamic panel effects. The following subsections provide a detailed discussion of the econometric framework, estimation strategy, and model specification.

3.1. Cross-Sectional Dependence (CSD) Test

This study analyzes CSD due to the interconnectedness of nations through various economic, social, and cultural networks, which may generate spillover effects. Both the Pesaran scaled LM test and the Pesaran [

74]. CSD test were employed to determine CSD. The equation for testing CSD is defined as follows:

3.2. Slope Homogeneity (SH) Test

A slope homogeneity (SH) test has been introduced and further developed [

73]. This test is employed in the present study to determine whether the cross-sections exhibit heterogeneous or homogeneous slopes. The SH test is a tool used in panel data analysis to assess whether the relationship between independent and dependent variables (i.e., regression slopes) remains homogeneous or heterogeneous across cross-sectional units, such as countries, firms, or industries. It examines whether the slope coefficients are identical for all cross-sectional units by testing the following hypotheses. Null Hypothesis (H

0): The slopes are homogeneous, indicating consistency across all units. Alternative Hypothesis (H

1): The slopes are heterogeneous, suggesting variation between units. The test is carried out as follows.

where

and

represent statistical measures [

72] used to test for SH. These delta statistics assess whether the assumption of homogeneous slopes holds in panel data regression. If the test results are significant (

p < 0.05), this suggests that slope heterogeneity is present, meaning the regression coefficients vary across cross-sections.

3.3. Second-Generation Unit Root Test

After confirming the presence of cross-sectional dependency in our model, comprehending the stationarity properties of the studied series is essential for empirical analysis. For this purpose, we employ the second-generation unit root test—specifically, the Cross-sectionally Augmented Im, Pesaran, and Shin (CIPS) test. This strategy is effective, particularly in cases of diverse slopes and CSD. The formula for this assessment is as follows:

where

and

illustrate the average first and lagged differences, respectively.

Additionally, the CIPS is determined by averaging each Cross-Sectionally Augmented Dickey–Fuller test (CADF), as demonstrated by the following equation:

The present study utilizes the CIPS unit root test [

72], predicated on the premise of CSD and informed by the results of the CSD test [

72]. This unit root test is utilized to examine the order of integration of the variables.

3.4. Cross-Sectionally Augmented Autoregressive Distributed Lag (CS-ARDL)

The CS-ARDL test [

75] is employed in this study to estimate both long-run and short-run relationships. Compared to alternative methods—such as mean group (MG), pooled mean group (PMG), augmented mean group (AMG), and common correlated effects mean group (CCMG) estimators—this approach offers greater reliability and efficiency. It effectively addresses challenges related to homogeneous slope coefficients, CSD, nonstationary, unobserved common factors, and endogeneity. This is crucial, as failing to account for unobserved common factors can lead to biased estimation results. The following equation represents the CS-ARDL model:

where

, with

and

representing the average cross-sections. Additionally,

denotes the averages of both the dependent variable and the regressors.

4. Results

The present analysis begins with an overview of descriptive statistics, as presented in

Table 2 across 218 observations. Statistics provide insights into the central tendency and dispersion of each variable, revealing that while some variables exhibit greater stability, others display more substantial variability across the dataset. The variable EDU (log of education expenditure) has a mean of 22.47 and a median of 22.27. FDI shows a mean close to zero, while TRAV has a mean of 1.05 and ranges from –3.51 to 3.57, indicating a wide distribution of tourist arrival values. TOU and its squared term TOU

2 display considerable spread, with values ranging from 5.86 to 10.86 and –2.99 to 0.24, respectively.

The GI (governance index) varies from 0.78 to 2.83, with a mean of 1.54. These descriptive statistics highlight noticeable variations in tourism-related and institutional variables across observations.

Given this variation across variables, it was essential to assess potential cross-sectional dependence (CSD) before proceeding with the estimation. Accordingly, a CSD test was conducted on the variables of interest, the results of which are summarized in

Table 3.

The findings indicate that all the examined variables exhibit CSD, as the test results lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis at a significant level of 1%. The significance of CSD stems from the interconnected nature of economies in a globalized world, particularly among GCC nations, where fluctuations in one country’s fundamental variables can influence other countries due to spillover effects. Additionally,

Table 4 confirms the presence of heterogeneous slope coefficients, highlighting differences in economic structures. Given the presence of CSD and heterogeneous slopes, the next step involves conducting a second-generation unit root test to examine the stationarity of the variables.

Table 5 presents the results of the stationarity analysis, indicating that EDU, TOU, GDP, and TRADE are stationary at level I(0), while TOU

2 and FDI become stationary at the first difference I(1) at a significance level of 5%.

A fundamental condition for the application of the panel CD-ARDL model is the presence of cross-sectional dependence and the integration of variables at either level I(0) or first-order I(1), which indicates that the variables are nonstationary at levels but become stationary after first-order differencing. This indicates that these factors may collectively possess a long-term equilibrium connection. The outcomes of the CD and CIPS assessments are recorded in

Table 6. The CD results indicate a robust rejection of the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence at the 1% significance level for all variables. These results indicate that all examined variables exhibit CSD. The presence of CSD within the data series renders standard unit root tests useless, as these tests depend on the assumption of cross-sectional independence. To address this issue, the present study utilizes a newly constructed CIPS unit root test that operates under the premise of CSD within the data series. The CIPS unit root test findings on level data suggest that the null hypothesis should be rejected at the 1% significance level, confirming that the studied series are free from unit roots. These results confirm that the variables of the present study exhibit a combination of I (0) and I(1) integration orders, suggesting cointegration among them. The variable EDU (log of education expenditure) has a mean of 22.47 and a median of 22.27. FDI shows a mean close to zero, while TRAV has a mean of 1.05 and ranges from –3.51 to 3.57, indicating a wide distribution of tourist arrival values. TOU and its squared term TOU

2 display considerable spread, with values ranging from 5.86 to 10.86 and –2.99 to 0.24, respectively.

The coefficient is highly significant at the 5% level, emphasizing the importance of past investments in education in improving income equality. Moreover, the results show that tourism revenue has a negative but not significant impact on income equality in the short run, while its lagged value (∆TOU(−1)) shows a positive and significant impact at the 5% level. This suggests that the effects of tourism revenue on income equality require a short lag to appear, highlighting a delayed response in distributive outcomes. The squared term of tourism (∆) is significant at the 10% level, indicating potential nonlinear effects, although its lagged value is statistically insignificant.

The effects of the other variables remain limited in the short run. Neither FDI nor its lag has a significant impact on income equality. The governance index GI records a negative association at the 10% level, implying that weaker institutional quality may undermine distributive outcomes. Tourist arrivals (TRV) exert no meaningful influence in either the current or lagged periods.

In the long run, tourism revenue (TOU) shows a significant and positive effect at the 1% level. Sustained growth in the tourism sector contributes to greater equality over time. The squared term is negative and insignificant, providing no evidence of a Kuznets-type inverted U-shape. The governance index shows a significant and negative effect on income equality in the long run. This suggests that even as institutional quality improves, the benefits of economic policies may not reach all segments of society equally. In the GCC context, stronger governance often supports large-scale tourism investments and state-led development, but without inclusive redistribution mechanisms, these gains tend to be concentrated among privileged groups. As a result, governance improvements may coincide with widening income gaps unless accompanied by targeted social and labor policies.

Linking the short- and long-run results, the model shows that income equality improves mainly through past tourism revenue and public spending on education. The strong effect of lagged education expenditure in the short run supports human capital theory, which sees education as a key driver of equal opportunity and higher earning potential. By investing in education, governments can raise the skill levels of the population and reduce income gaps over time. In the long run, tourism revenue continues to support equality, but the squared term is not significant, so the Kuznets curve does not apply in this case. Tourist arrivals show a small negative effect over time. FDI has no significant effect. These results highlight the need for long-term policies that expand access to quality education and ensure that tourism growth supports broader social goals.

To better understand the direction of influence between key variables, the Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality test,

Table 7, provides additional insights that complement the CS-ARDL findings. The Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality results reveal several significant directional relationships. A feedback (bidirectional) relationship emerges between education (EDU) and governance (GI), suggesting a mutual influence between government effectiveness and educational expenditure. Additionally, the analysis identifies a one-way causality from education to tourist arrivals (TRAV), indicating that improvements in education may enhance tourism capacity or service quality. FDI also Granger-causes education, implying that external capital inflows influence public spending patterns. Meanwhile, the squared term of tourism receipts (TOU

2) shows evidence of causing education. No causal effects are detected between total tourism receipts (TOU) and education, nor from education to FDI, underscoring the selective nature of these interactions. These findings reinforce the asymmetric and context-dependent links between tourism, investment, governance, and education within the GCC.

Dumitrescu and Hurlin build their panel causality test based on the usual Granger causality structure to determine if lagged values of one variable predict changes in another across panel units. However, it does not account for long-run equilibrium relationships, which are better captured through approaches such as the CS-ARDL framework [

72].

As a robustness check, the generalized linear model (GLM) was estimated. The results, presented in

Table 8, broadly support the findings from the CS-ARDL model. The coefficient for tourism receipts (TOU) is positive and highly significant, indicating that growth in tourism revenues tends to increase education expenditure. This outcome aligns with the view that tourism strengthens income equality by expanding human capital. The squared tourism term (TOU

2) does not reach statistical significance, which suggests no nonlinear relationship in this specification. The governance index GI shows a negative and statistically significant effect, possibly indicating structural weaknesses in public resource use. Tourist arrivals (TRV) also show a negative and significant effect, implying that an increase in the number of visitors does not automatically translate into better educational investment. FDI does not show a significant association with education expenditure. These results confirm the consistency of the main findings and reinforce the role of tourism revenue as a key driver of public education spending across GCC countries.

5. Discussion

The importance of tourism as a source of income for reducing income inequality can be inferred from the results of the CS-ARDL panel model. These estimation results provide valuable insights into the short- and long-term relationships between the studied variables, which include income equality (proxied by education expenditure), tourism revenue, foreign direct investment, the number of international tourist arrivals, and effectiveness of governance. While some variables exhibit significant influence, others appear to have limited or no measurable impact.

The results provide clear evidence that tourism revenue improves income equality, as shown by its significant and positive association with education expenditures. This pattern supports earlier findings by Blake [

76], who reported that tourism receipts increase public sector resources and promote equity through targeted government investment. In the GCC countries, where governments channel tourism revenue into education and infrastructure, this relationship aligns with human capital theory. By expanding revenue bases, tourism enables governments to fund education, which helps reduce inequality over time [

11].

In contrast, international tourist arrivals show a significant and negative relationship with education expenditure. This result diverges from studies that assume that more arrivals automatically generate broader social benefits. The explanation lies in the structural features of GCC tourism. Large-scale tourism in the region often relies on expatriate labor, short-term contracts, and low-wage employment. These dynamics limit wage growth among nationals and reduce the potential for inclusive development. Instead of fostering human capital formation, high volumes of arrivals may concentrate income among private operators without increasing public education budgets or reducing inequality.

The government effectiveness index exerts a negative and statistically significant effect on education expenditures. This result results to weaknesses in institutional mechanisms that should redistribute resources. Although tourism increases revenue, weak institutions may misallocate funds or prioritize nonsocial sectors. Studies by Barro [

58] and Kaufmann et al. [

77] support this view, showing that better governance improves the efficiency of public spending, especially in education.

FDI does not influence education expenditures in a meaningful way. This aligns with conclusions from Tsounta and Osueke [

78], who show that foreign investment often targets capital-intensive sectors with limited social spillovers unless governments implement deliberate redistribution policies.

These findings highlight the importance of treating tourism revenue and tourist arrivals as distinct variables. Revenue reflects financial capacity, while arrivals reflect volume and market structure. Without institutional reform and strategic planning, the tourism sector may grow without reducing inequality. GCC policymakers should recognize this distinction and focus on capturing tourism value through regulation, education investment, and labor market reform.

The governments of GCC countries have introduced various social aid programs to mitigate income inequality among citizens. For instance, the United Arab Emirates provides social welfare assistance to vulnerable groups, including widows, divorced women, individuals with disabilities, the elderly, orphans, and low-income families. Emirati nationals meeting the eligibility criteria can apply for financial support through the Ministry of Community Development’s online portal [

79]. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development oversees a comprehensive welfare system, offering support services for orphans, juvenile rehabilitation, elderly care, and financial assistance programs for job seekers. These initiatives aim to improve citizens’ well-being and ensure a stable standard of living at different life stages [

80]. In Oman, the Social Protection Fund administers multiple benefits, including financial support for the elderly, children, and individuals with disabilities, widows, and orphans, as well as income assistance for low-income families. These programs provide a basic level of financial security to vulnerable segments of society [

81]. These examples reflect GCC countries’ commitment to enhancing social welfare and addressing economic disparities among their citizens.

The results of the present long-run analysis reinforce the nonlinear relationship between tourism revenue and income equality, as evidenced by the significance of the squared tourism variable. Similar patterns have been reported, providing evidence of nonlinear dynamics in the tourism–income relationship [

82]. These findings confirm that tourism development can enhance economic progress and income equality over time when appropriate policies are implemented to mitigate the initial challenges of tourism growth. Additionally, GDP per capita emerged as the most significant long-term determinant in the CS-ARDL model. The strong, positive, and highly significant relationship between GDP and income equality aligns with findings that emphasize the critical role of economic growth in raising living standards and reducing inequality [

83,

84]. These results highlight the importance of sustainable economic growth in improving long-term economic outcomes and addressing income disparities.

In contrast, FDI has no significant impacts in either the short or long run. This aligns with conclusions that argue the effects of FDI and trade are often conditional on the presence of supportive policies and strong institutional frameworks [

23,

85].

Without these complementary factors, the potential benefits of trade and FDI may remain unrealized, as reflected by their insignificance in the model’s results. While, the CS-ARDL framework helps address some dynamic endogeneity through lag structure and cross-sectional dependence, the possibility of reverse causality or omitted variables cannot be fully ruled out. Future studies should consider instrument variable approaches or dynamic panel model to better isolate causal effect.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study investigates the dynamic relationships between tourism development, governance quality, FDI, and income equality, with income equality proxied by public education expenditure, in the GCC countries over the period from 2014Q1 to 2023Q4. Using the CS-ARDL model and the generalized linear model (GLM), the analysis reveals several key insights.

First, tourism revenue exhibits a significant and positive association with education expenditure, suggesting that increased earnings from tourism can enhance government capacity to invest in human capital. This finding aligns with human capital theory, which posits that investments in education contribute to reducing income inequality over time.

In contrast, the number of international tourist arrivals demonstrates a significant negative relationship with education expenditure. This outcome may reflect the structural characteristics of the tourism sector in the GCC, where mass tourism often relies on expatriate labor and may not translate into broader socioeconomic benefits for the local population. Such dynamics can limit the potential of tourism to contribute to income equality.

The governance index (GI) consistently shows a negative and significant effect on education expenditure, indicating that institutional weaknesses may hinder the effective allocation of resources toward education. This underscores the importance of governance reforms and transparency to ensure that tourism-driven revenues are utilized to promote equitable social outcomes.

FDI does not exhibit a statistically significant impact on education expenditure, suggesting that external capital flows may not directly influence domestic education budgets in the GCC context.

These findings highlight the necessity for policymakers in the GCC to distinguish between different dimensions of tourism—such as revenue versus arrivals—and to implement strategies that ensure tourism development contributes to inclusive growth. Emphasizing sustained investment in tourism revenue management, targeted education spending, and institutional reform can enhance the role of tourism in promoting income equality.

Future research could expand upon this study by incorporating additional variables and exploring the impact of other sectors on income equality in GCC countries.

Based on the findings of this study, policymakers in GCC countries should prioritize policies that promote economic growth, including investments in infrastructure, research and development, and human capital. Governments should also devise strategies to promote tourism while ensuring that it does not exacerbate income inequality. Policymakers can attract FDI by simplifying investment procedures and offering incentives to foreign investors. Finally, policymakers should develop trade policies that promote growth for all and reduce income disparities by protecting vulnerable industries, providing education and skill development opportunities, and facilitating workforce transitions to emerging sectors.

As discussed above, GCC countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman have implemented redistributive welfare programs that complement tourism development efforts and contribute to mitigating income disparities.

This study has some limitations, primarily due to the unavailability of data on income distribution in GCC countries, which necessitated using education expenditure as a proxy. The lack of disaggregated tourism and sector-specific FDI data also limits the depth of the analysis.