Abstract

The leadership of the university teacher has the most important role in the development of the educational institution and society. Universities are facing rapid societal changes and the need for innovative pedagogical approaches, including the potential for faculty members to emerge as leaders both within and beyond their classrooms, becomes increasingly salient. Teacher leadership in this context represents a collaborative ethos, where educators engage in shared decision making, curriculum development, and pedagogical innovation, thereby enhancing both academic and institutional outcomes. University teachers play a crucial role in achieving the 4th Sustainable Development Goal by leveraging their leadership skills to provide inclusive, equitable, and high-quality education. Teacher leadership and student satisfaction are considered to be interconnected but, in turn, teacher leadership is influenced by teacher disposition. The intricate interplay between professor leadership and student satisfaction within higher education institutions (HEIs) reveals significant implications for both faculty and student experiences. This study investigated two aspects: firstly, the effect of teacher dispositions, especially motivation, communication, conscientiousness, teacher efficacy and willingness to learn, teacher leadership, and secondly, how teacher leadership affects student learning satisfaction. A survey was developed using questionnaire structural equation analysis using SmartPLS 4.0. Three hundred eighty-nine students studying in public universities in Mongolia participated in the survey. The research results show that teacher dispositions such as motivation, communication, and conscientiousness positively affect teacher leadership. In addition, it was proven that teacher leadership positively affects student learning satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Leaders always bring change and innovation at any point in time. Because education produces leaders in all fields, leaders in this field are the most important people responsible for human development. A new era of change has come to the world. Leadership refers to professors’ capacity to guide, influence, and inspire their students and colleagues towards a shared educational vision while also navigating the complexities of academic life. When students feel heard and valued, their engagement and motivation tend to increase, promoting a sense of belonging essential for diverse classrooms. Studies indicate that effective induction programs significantly impact new teachers’ teaching expertise and job satisfaction, which aligns with the broader goal of enhancing student experiences [1].

When universities focus on the quality of knowledge and skills provided to students through e-learning, the teacher’s personal leadership will contribute more to the quality of education than e-technology and teaching tools.

Mongolian universities and colleges are making the digital transition and are working with concern on how to organize educational activities in an efficient, effective, and high-quality manner. Current and future students expect innovative methods and digital technology based on their needs that will allow them to learn regardless of space and time as they acquire knowledge and skills. During this transition, leaders have a critical role to play. Therefore, the development of the curriculum and its results are highly dependent on the leadership of the teacher. Comparatively, leaders are the foundation of any successful organization; each teacher’s leadership and involvement are the keys to successful learning outcomes and program development of universities. Teachers play a significant role in the students’ academic lives. They help pass essential knowledge that facilitates the students’ academic growth [2].

Researchers have studied the relationship between factors in teacher leadership development and leadership outcomes. For example, it is considered that community and colleague climate, institutional structure, and personal characteristics will affect teacher leadership, while it is believed that the quality of communication and work performance will be affected as a result of leadership [3,4]. Many researchers who have studied teacher leadership’s scientific and practical potential stated that teachers show leadership in encouraging collaboration, disseminating best practices, promoting the teaching profession, and understanding diversity [5,6,7].

However, there is still a demand for more research on teacher leadership. When we train teachers, we need to focus on their professional knowledge and skills and develop their character.

The research questions of this study are:

- RQ 1 How does a teacher’s disposition affect their ability to become a leader?

- RQ 2 How do teacher leadership and professional disposition affect student learning satisfaction?

- RQ 3 What is the relationship between teacher leadership’s effectiveness and teacher dispositions (motivation to teach, teacher efficacy, willingness to learn, conscientiousness, interpersonal communication), and how does it impact student learning satisfaction?

As a result of the research, every university teacher will understand that they should be a leader and will know what qualities they need to develop to become a leader.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Student Learning Satisfaction

The leading quality indicator of an educational institution is the satisfaction of stakeholders. Student satisfaction is an essential element of quality education that optimizes learning [8]. In addition, students’ satisfaction with the learning process is the basis of effective learning. Students’ learning satisfaction is a collection of personal inner feelings of learners in the learning process [9]. Satisfaction and positive feelings are generated by the learning process experienced by the individual in learning activities [10].

The learner is satisfied if they can obtain the knowledge and skills from the learning activity but not if they cannot. Therefore, the teacher’s main responsibility is to provide knowledge and skills to the students, especially to meet their expectations. Of course, it is difficult for teachers to fulfill the expectations of the chosen subject and the teacher because they deal with students of many cultures, different personalities, and different levels of knowledge and abilities. On the other hand, most university students are young people who have completed secondary education and are studying at universities. Many factors influence their learning, such as new friends, learning styles, teachers, different communities, and cultural differences. In particular, the teacher’s leadership, personality, and attitude will affect the student’s success in learning. Learners’ perception of learning results comes from the difference between the actual learning content obtained in the learning process and the expected learning results, which is learning satisfaction [11]. Also, student satisfaction is the subjective perception, on students’ part, of how well a learning environment supports academic success. Also, the teacher’s personality, behavior, and effectiveness [12] motivate student satisfaction.

2.2. Teacher Leadership

Teacher leadership plays an important role in teachers’ continuous professional development and the long-term improvement of educational outcomes [4,5,13]. Leading teachers are coordinators, coaches, specialists, head teachers, department heads, and mentors [14]. In the traditional sense of leadership, teachers have two options for work responsibilities: one is to only teach and work until retirement or to leave teaching and take a leadership position [2]. According to the traditional understanding of leadership, it was understood that leadership is related to the position of a leader. Teacher leadership can be defined as formal and informal. Formal leadership refers to those who hold formal positions and titles as members of a school’s management team; informal leadership refers to a person’s behavior and skill-based leadership ability, which is successfully encouraged by others.

In their research, Silva, Gimbert, and Nolan [15] defined the evolution of formal teacher leadership into three stages: in the first stage, schools focused on supervising teachers and appointed department heads and master teachers. Their managerial role was seen as passive in the role of teachers. In the second stage, the teacher leaders were promoted to head of academic training and head of the program. Although some strengths emerged, these roles distinguished teacher leaders from their colleagues and reduced their influence on program improvement. In the third stage, the teacher prefers to lead the teacher’s professional development activities. This is because teachers actively participate in solving problems at the university level, such as improving the content of courses and programs without being told by anyone, and then give their opinions and votes on the university’s mission, vision, strategy, relevant rules, and regulations.

Based on the three stages of teacher leadership development, the official leadership of teachers is not very effective. Although this conclusion was drawn at the secondary school level, we believe it reflects a similar trend in the development of the educational system as observed in the evolution of teacher leadership across all levels of educational institutions. We particularly emphasize the significance of individual teacher characteristics in strengthening leadership among university teachers.

There was a time when teachers’ leadership was understood as related to their position, authority, and official duties. In other words, the teacher’s leadership was evaluated in terms of position and authority. However, according to Barbara B. Kevin, every teacher is a leader, and informal teacher leadership is born from the ranks of teachers who demonstrate high levels of leadership and provide lessons for formal leaders to improve their leadership practices. Informal teacher leadership is not a formally assigned role but a process created informally through specific actions [16].

Because we want to emphasize that every teacher needs to be a leader in the course, class, school, and community, teachers must take the lead in many areas. For example, new trends such as digital technology and the introduction of blended learning teaching methods have recently emerged, so new roles and responsibilities may continue to increase their leadership. Therefore, teacher leadership highly depends on the teacher’s behavior and skills. In particular, the teacher’s personal beliefs, values, ethics, character, and positive attitude reach the students through the teacher’s leadership. Leadership is a dynamic process that involves influencing individuals and groups to direct their actions towards achieving common goals. In this context, a leader is an authority figure who can motivate, guide, and inspire others, getting them to work together to achieve results, as teachers do with the students [17]. Northouse indicates that: “(a) Leadership is a process, (b) leadership involves influencing others, (c) leadership happens within the group, (d) leadership involves goal attainment”. Therefore, researchers define “leadership” as a process of influencing others to achieve their goals by leading with their beliefs, values, ethics, character, knowledge, and abilities, and every teacher should have it. In recent years, there was a significant shift in how educational leadership is conceived, especially within schools. Educational Leadership and Management (EDLM) researchers have raised an important thought: school leadership should not be seen only as a role involving the school leader or a top figure but as a distributed process involving the entire school staff, including teachers [4,18,19].

Teacher leadership in education affects the university’s reputation, teacher performance, student success, and social development. Personal teacher leadership has a greater impact on program outcomes, learning quality, and student satisfaction. Teacher leadership is an important component of student success, and teachers must be included in the decisions that affect students [20]. Teacher leadership aims to promote student learning achievement, including developing the school organization altogether [3].

Wenner and Campbell [3] argued that teacher leaders’ roles transcend the classroom walls in working towards change and school improvement. Leadership opportunities for teachers are critical to addressing and solving the problem of recognizing and valuing the talents of those teachers who contribute significantly to student learning, collaboration among colleagues, and the overall improvement of the school system. Creating leadership spaces for teachers not only promotes instructional innovation but also reinforces a sense of responsibility and belonging to the entire school community [21,22].

2.3. Teacher Leadership in Higher Education

Analyzing the scientific literature on teachers’ leadership impact in HEIS, it is possible to find different aspects and indications of the teacher leadership role and its emergences, as teacher leadership and the HEI educational process [23,24,25,26,27,28]; teacher leadership and personal skills and perceived roles [23,27,28,29,30]; leadership styles, and performance [25,26,31,32,33]; teacher leadership formation, and barriers [26,27,34]. Speaking about teachers’ leadership and the impact on the HEI process, some researchers are analyzing the role of leadership in research [23,24], research about teacher leadership and faculty development [25,26,27], and research about teacher leadership and curriculum development [28]. In the HEIS environment, teacher leaders often serve as catalysts for change, advocating for pedagogical practices that reflect contemporary educational theories and respond to diverse student demographics. Such dynamics underscore recognizing and cultivating teacher leadership within universities as integral to successful curriculum development and institutional effectiveness. Teacher leaders offer invaluable insights into student learning and engagement complexities [35,36]. Faculty collaboration emerges as a pivotal component in successfully reforming university curricula, facilitating a dynamic exchange of ideas that enhances educational outcomes. By fostering sustained collaboration among faculty members, institutions can align strategic priorities, leading to cohesive and innovative curriculum designs that are responsive to the diverse needs of the student body. The collaborative efforts create a supportive infrastructure for curriculum development and ensure that reforms are sustainable, enhancing faculty ownership of the curricular process and enriching the academic experience for all stakeholders involved. Harrison and Killion (2007) [23] identify several key roles that professor leaders may assume, which include: “resource provider, instructional specialist, curriculum specialist, classroom supporter, learning facilitator, mentor, school leader, data coach, catalyst for change and learner”. In their 2007 work, Harrison and Killion [23] explored the diverse ways professors demonstrate leadership in educational settings. They emphasize that leadership among professors is not restricted to formal, designated roles but also includes informal leadership that develops through interactions with peers and the academic community. For Ball [24], leadership in universities “can improve research outcomes, staff enthusiasm, and commitment”.

In his research on other aspects of teacher leadership skills, da Silva Freitas Junior et al. [27] analyzed which skills are more important for a leader. They found that the skills are confidence, open-mindedness, being an example, influencing, and establishing trust. They also proposed a plan for leadership development.

Similarly, researchers have drawn attention to the leadership role of university faculty, including their dispositions [29]. University faculty and leadership development have focused on research and outcomes rather than teaching. In some cases, it resulted in teaching deficiencies, as highlighted by Dijk et al. [37] In recent years, employers have particularly underscored the value of soft skills in the workspace, including leadership skills. This certainly interests us since university faculty could themselves be better at leadership and take their students to development. This emphasis on the value of soft skills in the workplace is enlightening, as it underscores the importance of these skills in the professional development of university faculty and the subsequent impact on student learning and development.

Professional development programs in higher education may concentrate on developing the leadership skills of academic staff, such as leading teams, mentoring colleagues, and designing innovative teaching methods.

2.4. Teacher’s Professional Disposition

A university teacher can be said to be a dual professional. This is because a university teacher not only has a profession such as an engineer, veterinarian, or economist but also learns the professional approach and quality of teaching and carries out teaching work. In addition to professional knowledge and skills, individual teaching skills and abilities continue to change based on learner behavior, attitudes, and needs. Therefore, researchers are paying attention to the study of the personal and professional dispositions of teachers. The reason is that professional dispositions are the values, commitments, and professional ethics that influence behaviors towards students, families, colleagues, and communities that affect student learning, motivation, development, and an individual’s professional growth (NCATE) [38]. Teacher dispositions, understood as professional virtues, mental and behavioral qualities and habits, are key elements that directly influence teaching effectiveness and the quality of learning. These dispositions are not innate, but develop through experience, professional commitment, continuing education and dialogue with those involved in the educational process (students, families, colleagues and the community) [39]. Shari et al. [40] noted that dispositions are “ongoing tendencies that guide intellectual behaviour”.

Furthermore, Misco and Shiveley [41] suggested that dispositions have three different categorical aims: (a) dispositions as personal virtues, (b) dispositions as educational values, and (c) dispositions as societal transformation. The definition of disposition is mainly related to teachers’ characteristics. The definition provided by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) in 2008 emphasizes the importance of dispositions as professional attitudes, values, and beliefs that teachers express through both verbal and nonverbal behaviors [38]. These dispositions are important as they are related to the ability to relate positively and professionally to students, families, colleagues, and the community. A teacher’s personality is directly related to student academic success, particularly the teacher’s communication skills, honesty, and motivation [42,43,44]. West et al. [45] stated that motivation to teach, teacher efficacy, willingness to learn, conscientiousness, and interpersonal communication skills are the main characteristics of the teacher’s profession.

A teacher’s motivational personality affects working enthusiastically, increasing professional involvement, leading, developing, and creating value [46,47]. Rubdy et al. [48] and Dörnyei Ushioda’s [49] research is helpful for understanding how motivation is not a linear and static process but a complex dynamic involving multiple factors: the initial reasons for undertaking an activity (initiating and sustaining motivation) and the internal and external resources needed to maintain it over time. In addition, the motivational character of the teacher makes the student actively motivated to learn [50]. It is observed that the characteristics of modern student’s behavior are that they are reprimanded and pushed with too many tasks, which is likely to hurt the learning outcomes. Rather, it is more necessary to encourage and motivate them to learn effectively by treating them kindly, listening carefully to their intentions and supporting them. Therefore, we believe this is one of the important leadership qualities that a teacher should have.

Teacher self-efficacy is one of the most important factors in teacher leadership. Bandura [51] first wrote about this personality within the socio-cognitive theory developed by social scientists. This character is the quality of a person’s actions to achieve desired goals confidently. Teacher self-efficacy increases their ability to lead in any activity. A self-confident person can lead others and help them achieve their goals.

On the contrary, a person lacking self-confidence is less likely to be listened to and followed by others. Especially in schools, teacher self-efficacy may be conceptualized as individual teachers’ beliefs in their abilities to plan, organize, and carry out activities required to attain given educational goals [52]. Therefore, this quality is one of the most important qualities that a teacher should have because a teacher can be confident in front of their colleagues and students and lead them to work and learn successfully.

Willingness to learn is an important aspect of teacher leadership. A willingness to learn is an impulse, desire, or readiness to acquire new and developing knowledge [53]. In other words, people willing to learn constantly seek new things, do not stagnate in development, and follow modern trends. Factors that influence employees’ willingness to learn and share knowledge are the perception of organizational culture, trust, infrastructure, and leadership [54].

Conscientiousness is one of the professional characteristics that influence effective teacher leadership. It is defined as an individual’s ability to show self-discipline and strive for competence and achievement [55]. Conscientiousness is an important quality of an individual to perform their duties well and be disciplined. According to the Five-Factor personality theory, conscientiousness is a quality that is more suitable for people with leadership skills, long-term planning, communication support, and technical skills [56]. Conscientiousness is the most reliable measure of leadership effectiveness. Singh [57] also argues that extraversion and conscientiousness are important personality attributes for leadership effectiveness. According to the above researchers, conscientiousness is one of the important qualities that everyone should have. In our research, this personal quality is one of the most important professional dispositions for a teacher because the teacher is the most important person who influences their students to learn in a disciplined, responsible and conscientious manner. From this teacher characteristic, students are more likely to learn again and become good leaders in the future.

Interpersonal communication skills are the most important qualities that teachers should have in educational institutions. The main focus of today’s educational organization is interpersonal relationships. University is a learning environment, and sharing knowledge and experience, teamwork, intellectual modeling, and systematic thinking are most important in daily school life because they manifest in interpersonal relationships [58]. Therefore, communication competence is one of the key factors for effective work and well-being of employees. Hence, modern researchers [59,60,61,62,63] underline the importance of human interpersonal communication competence.

Therefore, a form of teacher leadership in the university environment is manifested in their interpersonal relationships. Wood [59] and Purhonen [60] argue that interpersonal communication depends on the context or a particular situation, people’s ability to communicate and their motivation, listening skills, cultural literacy, language, as well as skills marked by Wood [59], namely “developing a range of communication skills; adapting communication appropriately; engaging in dual perspective; monitoring communication; and committing to effective and ethical interpersonal communication”. From the above research, we have seen that the main characteristics of the teacher’s professional personality influence the teacher’s enthusiasm for leadership.

According to the literature review, the teacher’s disposition and leadership positively affect student learning satisfaction. In our study, we examined a theoretical model proposing that teacher leadership mediates the relationship between student learning satisfaction and teachers’ professional dispositions in the context of higher education.

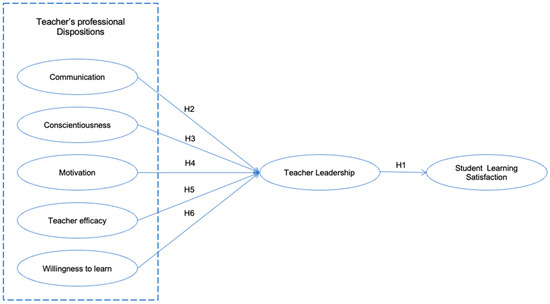

Our research is proposed following the research model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model of effects of teacher dispositions and leadership on student learning satisfaction.

Considering the literature review, we hypothesize that teachers’ positive leadership will affect students’ learning.

H1.

Teacher leadership positively influences student learning satisfaction.

H2.

Teacher communication positively affects teacher leadership.

H3.

Teacher conscientiousness positively affects teacher leadership.

H4.

Teacher motivation to learn positively affects teacher leadership.

H5.

Teacher efficacy positively affects teacher leadership.

H6.

Teacher willingness to learn positively affects teacher leadership.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method

This research was conducted using a questionnaire survey and quantitative methodology. We tried to determine how teachers’ professional dispositions influence their leadership skills and student satisfaction.

Student satisfaction was used as the dependent variable of this study, and the main professional dispositions of the teacher. The indicators, motivation to teach, teacher efficacy, willingness to learn, conscientiousness, and interpersonal communication skills, were taken as the independent variables. However, teacher leadership was chosen as the intermediate variable. The following 5 points determine the scale of these variables. These are: (1) strongly disagree; (2) disagree; (3) neither agree nor disagree; (4) agree; (5) strongly agree. In order to determine the teacher’s professional dispositions, a total of 25 questionnaires of the teacher personality dimensions of the scholar Conor West [45] were used, slightly modified according to the country’s behavior. Based on the theoretical research performed by previous researchers, eight questionnaires were used in the research of Sally Ann Sugg [64] to determine the variable of teacher leadership. In addition, Sun et al. [65] obtained the student satisfaction questionnaire from 6 questionnaires. Before submitting all questionnaires in the Mongolian language, all measures were adopted to ensure accurate translation, taking into mind cultural factors. The translation was made by professors teaching English and by professional translators. The translation results have been discussed with linguistic experts, psychologists, and pedagogic experts. The adopted Student Satisfaction Questionnaire is mainly for K12 students, but taking in mind the peculiarities of the Mongolian HE system and that our students are adolescents, this questionnaire fits with Mongolian students’ characteristics.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The survey was conducted among 1st- to 5th-year students of 5 public universities in Mongolia from October to December 2022. A total of 390 students participated in this study; 44.7% were male and 55.3% were female.

In the survey, 1st- to 5th-year students participated equally, which means that they are able to differentiate and evaluate the learning experience, teacher knowledge, and leadership skills. Freshmen made up 31.1% of the students who participated, while seniors participated the least at 15.1 percent (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics.

3.3. Results

The measurement analysis aims to determine the internal consistency reliability of latent variables. Two types are examined for validity assessment: convergent validity and discriminant validity. Hair et al. [66] recommended that indicators with weaker outer loadings can be retained if other indicators with high loadings explain at least 50 percent of the variance (AVE = 0.50). Composite reliability (CR) is also used to measure internal consistency and must not be lower than 0.7 [67]. Hence, AVE for all constructs was found to be adequate—communication (0.936), conscientiousness (0.918), motivation (0.928), teacher efficacy (0.950), teacher leadership (0.940), willingness to learn (0.916), and learning satisfaction (0.960)—thereby confirming the convergent validity of the constructs. Also, the results provided in Table 2 indicate that CR (composite reliability) values for all the constructs were above the cut-off value 0.7—communication (0.937), conscientiousness (0.919), motivation (0.929), teacher efficacy (0.951), teacher leadership (0.944), willingness to learn (0.920), and student learning satisfaction (0.805)—thereby showing the high internal consistency of the measures.

Table 2.

Internal consistency reliability and convergent validity.

Discriminant validity (DV) refers to the extent to which the constructs used in the model are distinct [59]. Discriminant validity ensures that latent constructs measure distinct aspects of reality and do not overlap, allowing us to ensure that latent variables are distinctive and do not measure the same phenomenon [68]. To test the DV we used “average variance extracted” (AVE). To have good discriminant validity, the AVE of a construct should be greater than 0.50, meaning that the latent construct explains more than half of the variance in its indicator variables. This study shows that all constructs are highly correlated with other constructs. Table 3 indicates AVE’s square root is higher than the correlation values of other constructs on both horizontal and vertical sides, which shows no discriminant validity issues.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

3.3.1. Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity is a statistical phenomenon that occurs when two or more independent variables in a regression model are highly correlated, indicating a strong linear relationship between the predictor variables. There are several ways to identify multicollinearity in a regression model, and we used VIF (variance inflation factor). The VIF measures how much the variance of a regression coefficient is increased due to collinearity with other predictor variables; a VIF above 10 indicates high collinearity, and a VIF of approximately 1 indicates no collinearity [69]. Hair et al. [70] recommend a cut-off value of 10.0 for multicollinearity. The VIF results are provided in Table 4 for each of the 39 latent constructs. Since the VIF values were lower than the threshold value of 5.0, there was no issue of multicollinearity between the latent constructs.

Table 4.

Inner VIF values.

3.3.2. Structural Models

Structural models are econometric representations of decision-making behavior.

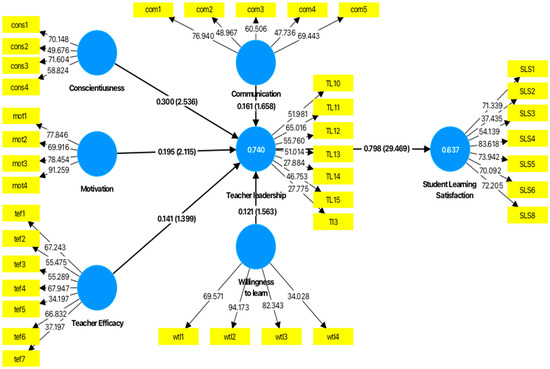

The causal relationship between the constructs is assessed by using structural models. To estimate the statistical significance of the hypothesized model, Hair [70] suggested using the bootstrapping technique with resampling (5000 resamples). The research results show that teacher leadership (H1 β = 0.798, t = 29.471, p > 0.000) positively affects student learning satisfaction. Also, teacher’s disposition (H2 Communication β = 0.176, t = 2.173, p > 0.030; H3 Conscientiousness β = 0.309, t = 3.009, p > 0.003; H4 Motivation β = 0.190, t = 2.107, p > 0.035) has a significant effect on teacher leadership. However, teacher efficacy (H5 Teacher efficacy β = 0.131, t = 1.311, p > 0.190) and willingness to learn (H6 Willingness to learn β = 0.113, t = 1.450, p > 0.147) have not been supported (Figure 2 and Table 5).

Figure 2.

Results of the proposed model.

Table 5.

Summary of hypothesis testing result (bootstrapping report).

Figure 2 illustrates that the independent variables, teacher’s professional dispositions, significantly impact teacher leadership. R2 shows the variance explained by the independent variables in the corresponding dependent variables of this study. As evident from the R2 value, teacher dispositions explained 74.1 percent (R2 = 0.741) of the variance in student learning satisfaction while explaining 63.7 percent (R2 = 0.637) of the variance in student learning.

3.3.3. Mediation Analysis

Mediation analysis was performed to assess the mediation role of teacher leadership in teacher dispositions and student learning satisfaction. H1 (TL → SLS) showed a strong relationship, as it is possible to see in Table 6, suggesting that effective teacher leadership significantly enhances student learning satisfaction. The results of relevant significant direct effects of TL and SLS (H1: β = 0.798, t = 29.469, p < 0.000); H3: Cons and SLS: β = 0.300, t = 2.545, p < 0.011), H4: Mot and SLS: β = 0.195, t = 2.092, p < 0.036). However, not significant H2: Com and SLS: β = 0.161, t = 1.647, p < 0.100, H5: Tef and SLS: β = 0.141, t = 1.394, p < 0.163, H6: WTL and SLS: β = 0.121, t = 1.559, p < 0.119.

Table 6.

Direct relationship.

The indirect effect of teacher dispositions (communication, conscientiousness, motivation, teacher efficacy, willingness to learn) on student learning satisfaction through the mediation variable of teacher leadership found that two hypotheses were significant (H3: β = 0.152, t = 2.092, p < 0.036); (H4: β = 0.152, t = 2.092, p < 0.036), respectively, as indicated in Table 7. These values show that both conscientiousness and motivation contribute to student learning satisfaction. Other relationships, such as H2 (Com → SLS), H5 (Tef → SLS), and H6 (WTL → SLS), had higher p-values (0.100, 0.163, and 0.119), indicating weaker or non-significant associations.

Table 7.

The results of mediation (specific indirect effect).

4. Discussion

Our research has focused on teacher leadership in higher education in Mongolia. This study had two objectives: first, to identify teacher dispositions that are more needed in teaching work and their effect on teacher leadership; second, to examine how teacher leadership influences student learning satisfaction, considering student satisfaction is a principal condition for an inclusive environment. Also confirming the extent to which the sense of belonging and inclusion are correlated with student satisfaction are the research data of Mok and Flynn [71], which show that student satisfaction and inclusive classes are correlated. Fan X et al. [72] also reached the conclusion that sense of belonging and friendships are both correlated and predictors of life satisfaction of students. Doğan and Celik’s [73] research indicate that factors contributing to student satisfaction, such as fulfilling individual needs and cultivating feelings of belongingness, are essential for fostering an inclusive learning environment.

As hypothesized, teacher leadership strongly influences student satisfaction (R2 = 0.637). This is consistent with previous researchers’ results. For example, Regmi Adhikary [8] suggested that teacher leadership styles positively affect student satisfaction. Also, Xiaoqin Liu et al. [74] found that university teacher leadership impacts student learning satisfaction. Through their leadership, university teachers can motivate students to study well and lead them to their goals [75]. Barth [76] noted that all teachers can lead and believes that all teachers must lead to make the school a field for students to learn. Teacher leadership can increase students’ learning satisfaction and influence their quality of learning. Our research confirms that teacher leadership positively impacts student motivation and confirms the results obtained by Trigueros et al. [33] and Espinosa, V. and González, J. [35]. Also, the research of Igwe et al. [77] confirms the results of our research regarding the positive impact of teachers’ leadership on students’ motivation and performance. When students perceive their teachers as constructive leaders and care about well-being and success, they feel more motivated to do their best. This trusting and supportive relationship creates a positive and nurturing environment that fosters learning and higher self-esteem [78,79].

Teachers who adopt a leader’s behavior convey to students that they are guiding, recognizing, and valuing their efforts. This leads to a virtuous circle: students feel more confident and supported, become more engaged, improve, and feel increasingly satisfaction. In a positive educational context, the school experience becomes more fulfilling and challenging for students and teachers [80]. Therefore, the university should encourage every teacher to become a leader.

Teacher’s efficacy and willingness to learn were not significant in our research. Students might not always recognize a teacher’s willingness to learn because they often assume their teachers are already highly educated and might not consider these factors relevant to their satisfaction. Our research findings are confirmed by Lyu T et al., 2023 [81], who showed that interactions between teachers and students are more important for student satisfaction than just teacher self-efficacy alone. about the literature on the connection between teacher traits and student satisfaction shows complex interactions that often go against the idea of a straightforward link. Studies show that although teacher self-efficacy is important for improving classroom quality and encouraging positive student behavior, it does not automatically lead to higher student satisfaction [82]. Teacher self-efficacy is associated with factors like job satisfaction and classroom management, which might help the teacher’s well-being but do not necessarily improve how students feel or their emotional involvement. This indicates that while teacher traits matter, they work within a complicated mix of contextual and individual factors that shape the student experience, thus questioning the idea that only efficacy can drive satisfaction. When looking at what satisfies students, it is clear that engagement and motivation are more important than how effective teachers are or how willing students are to learn. Student engagement, which includes participating in activities and feeling emotionally connected, is key in satisfaction and encourages students to get involved in their learning. Studies show that when students are engaged, their intrinsic motivation grows, improving their academic success and sense of belonging. While teacher efficacy can affect teaching quality, its direct effect on student satisfaction is unclear and needs further research to be better understood.

5. Conclusions

The exploration of teacher leadership within university contexts illuminates its multifaceted nature and underscores its imperative role in shaping the future of higher education. In fostering environments where educators are empowered to lead, universities can cultivate a more profound sense of belonging and purpose within their academic communities. Effective teacher leaders foster collaborative cultures that empower faculty and enhance student learning outcomes, illustrating the interconnectedness of social capital and academic success. Integrating teacher leadership roles enriches the educational landscape and cultivates an atmosphere where innovation can thrive. Furthermore, the adaptability exhibited by these leaders in addressing the diverse needs of their colleagues highlights a commitment to continual professional development and lifelong learning. Teachers with a deep passion for teaching and learning are often more enthusiastic about taking on leadership roles. Their dedication to education pushes them beyond regular classroom duties, motivating them to innovate, inspire others, and contribute to school improvement. Enthusiasm for leadership is closely tied to a teacher’s intrinsic motivation to help students and colleagues grow academically and personally. The personal dispositions of university teachers influence their leadership. The results of our research show that teachers’ communication, conscientiousness, and motivational qualities influence their leadership. Therefore, interpersonal communication is the most important factor in teacher leadership. Through relationships, a teacher can attract others and influence them and others to achieve their goals to promote inclusivity and sustainability. In modern times, the teacher’s leadership is not only in teaching and research activities but also in social development, helping people to live well and leading them to achieve their goals.

However, the teacher’s efficacy and willingness to learn decrease the teacher’s leadership. The low impact and lack of support for these hypotheses may be due to the lack of understanding of the student’s emotions, attitudes, and teacher behavior when completing the survey. Of course, many material and non-material factors affect a student’s learning satisfaction.

This study examines the impact of non-material factors on student learning satisfaction, including teacher disposition and leadership skills, in a case study of public universities. This research needs to be further expanded and studied in detail. The impact of student satisfaction on inclusion within educational environments cannot be overstated, as it fundamentally influences both academic outcomes and social cohesion among peers. When students feel understood and supported, as evidenced by the study demonstrating that professional guidance significantly enhances learning motivation [75], their overall engagement and satisfaction will likely increase. This environment of encouragement fosters a sense of belonging, a critical component of inclusive educational practices. Promoting a culture of respect and support is essential for enhancing individual performance and cultivating an inclusive atmosphere that benefits the educational community as a whole. Addressing these dynamics is vital for achieving both emotional and academic success for all students. Students who feel valued and understood in inclusive environments demonstrate higher levels of engagement and academic achievement. This correlation underscores educational institutions’ need to prioritize diverse representation and the development of supportive frameworks that promote positive student experiences.

Further research studies are crucial to expanding the knowledge on student satisfaction, teacher leadership, and the impact on an inclusive and sustainable environment, as highlighted in the provided passage. The current study, while insightful, was conducted with undergraduate students and leaves steps for future investigations with more diverse populations. This study presents some limitations that can be explored in the future: the leadership styles of university teachers should be determined; it is necessary to determine which forms of teacher leadership have the most significant impact on student and educational institution performance. Another limitation is the sample. Conducting similar research with different sample groups from various regions in Asia and globally would enhance the generalizability of the findings. For instance, comparing results from different cultural and educational contexts would offer valuable insights into whether the factors contributing to student satisfaction or dissatisfaction are universally shared or vary depending on local contexts.

6. Limitations and Further Considerations

The mediated relationship between teacher leadership and student satisfaction is a multifaceted dynamic that plays a pivotal role in educational success. When teachers adopt leadership roles through mentoring, collaboration, or curriculum development, they foster a culture prioritizing student engagement and accountability. This, in turn, can lead to increased student satisfaction as learners feel more supported and valued in their educational experiences. However, relying solely on one data source, such as student surveys or teacher self-assessments, may yield a skewed understanding of this intricate relationship. Insight derived from diverse sources is essential to capture a comprehensive view of how teacher leadership ultimately shapes student perceptions and experiences, paving the way for practical improvements in educational practices and policies. Including variables such as demographics, teaching methodologies, or teacher job satisfaction in the research could provide deeper insights into the intricate relationship between teaching practices and student experiences.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the research presented in this paper and to the preparation of the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was written within the EU KA 2 CBHE Erasmus project, Development of Teacher Leadership Skills (DeSTT) project (Ref.:609905-EPP-1-2019-1-IT-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP (2019-1962/001-001)), the ERASMUS Plus program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to cooperation between the six state-owned Mongolian Universities. This collaboration aims to exchange information and experience on various aspects of higher education development, define the directions and forms of mutual learning and cooperation, and coordinate their research and training efforts to foster joint development. http://www.mgl6.elf.gov.mn/page/6 (accessed on 15 September 2022). The approval of the Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board is unnecessary, underscoring the value of mutual learning and collaboration in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Garcia-Vallès, X.; Badia Martín, M.; Gavaldà, J.M.S.; Pérez Romero, A. Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Training for Inclusive and Sustainable Education: From University Classrooms to School Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, L.L. Behaviors of Teacher Leaders in the Classroom. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 12, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wenner, J.A.; Campbell, T. The Theoretical and Empirical Basis of Teacher Leadership. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 87, 134–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York-Bar, J.; Duke, K. What Do We Know About Teacher Leadership? Findings From Two Decades of Scholarship. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 255–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R. Finding a New Way: Leveraging Teacher Leadership to Meet Unprecedented Demands; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muijs, D.; Harris, A. Teacher Leadership—Improvement through Empowerment? Educ. Manag. Adm. 2013, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijs, D.; Harris, A. Teacher-led school improvement: Teacher leadership in the UK. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, R. Leadership Style and Student Satisfaction: Mediation of Teacher Effectiveness. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chun-Hsiung, H. Exploring the Continuous Usage Intention of Online Learning Platforms from the Perspective of Social Capital. Information 2021, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munchow, H.; Bannert, M. Feeling good, learning better? Effectivity of an emotional design procedure in multimedia learning. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A.; DiLoreto, M. The Effects of Student Engagement, Student Satisfaction, and Perceived Learning in Online Learning Environments. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2016, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Komarraju, M.; Karau, S.J.; Schmeck, R.R.; Avdic, A. The Big Five personality traits, learning styles, and academic achievement. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangin, M.M.; Stoelinga, S.R. Teacher leadership: What it is and why it matters. In Effective Teacher Leadership: Using Research to Inform and Reform; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Neumerski, C.M. Rethinking Instructional Leadership, a Review. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 49, 310–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.Y.; Gimbert, B.; Nolan, J. Sliding the Doors: Locking and Unlocking Possibilities for Teacher Leadership. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2000, 102, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, C. Teacher Leadership That’s Strengthens Professional Practice; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2006; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Harris, A.; Ng, D. A review of the empirical research on teacher leadership (2003–2017). J. Educ. Adm. 2019, 58, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spulber, D.; Figus, A. The competence leadership from philosophical and political direction and the challenges in education. Geopolit. Soc. Secur. Freedom J. 2022, 5, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.J. Transformative Professional Development: Discovering Teachers’ Concepts of Politicised Classroom Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, Unpublished Dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 87–134. [Google Scholar]

- Datnow, A.; Hubbard, L.; Mehan, H. Extending Educational Reform: From One School to Many, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, A.C.; Stubbs, H.S. From Science Teacher to Teacher Leader: Leadership Development as Meaning Making in a Community of Practice. J. Sci. Educ. 2003, 87, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Killion, J.P. Ten Roles for Teacher Leaders. Educ. Leadersh. 2007, 65, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S. Leadership of Academics in Research. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 449–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Suresh, M. Factors influencing organizational agility in higher education. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumurkhuu, U.; Baatar, B.; Purevsuren, T.; Batchuluun, E. University in Changing Environment and University Employees’ Attitudes towards Ideal Leadership. Geopolit. Soc. Secur. Freedom J. 2022, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas Junior, J.C.d.S.; Souza, I.R.; de Cabral, P.M.F.; Bruno, L.V.P. Leadership: Challenge or need in faculty development of the universities. Dev. Stud. Res. 2021, 8, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, V.; Fisk, A. Considering Teaching Excellence in Higher Education: 2007–2013: A Literature Review Since the CHERI Report 2007; Project Report; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghamrawi, N.; Abu-Shawish, R.K.; Shal, T.; Ghamrawi, N.A.R. Teacher leadership in higher education: Why not? Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2366679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.A. Changing Role for University Professors? Professorial Academic Leadership as It Is Perceived by “The Led”. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 41, 666–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonderiene, R.; Majauskaite, M. Leadership style and job satisfaction in higher education institutions. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Idris, M.; Amin, R.U. Leadership style and performance inhigher education: The role of organizational justice. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 26, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R.; Padilla, A.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Mercader, I.; López-Liria, R.; Rocamora, P. The Influence of Transformational Teacher Leadership on Academic Motivation and Resilience, Burnout and Academic Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemodanova, G.; Olkova, I.; Gumel, E.; Volchkova, N.; Spulber, D. Formation of Future Teachers’ Leadership Competence at a Higher Education Institution. Geopolit. Soc. Secur. Freedom J. 2022, 5, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, F.; González, L.J. The effect of teacher leadership on students’ purposeful learning. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2197282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, N.; Bamber, C. The Role of Leadership in Promoting Student Centred Teaching and Facilitating Learner’s Responsible Behaviour. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 11, 208–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, E.E.; Tartwijk, J.V.; Schaaf, M.F.; Kluijtmans, M. What makes an expert university teacher? A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks for teacher expertise in higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCATE. Professional Standards for the Accreditation of Teacher Preparation Institutions; National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 1–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rademaker, S.M. Connective Capacity: The Importance and Influence of Dispositions in Special Education Teacher Education; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shari, T.; Eileen, J.; Perkins, D. Teaching Thinking Dispositions: From Transmission to Enculturation. Teach. High. Order Think. 1993, 32, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Misco, T.; Shiveley, J. Making Sense of Dispositions in Teacher Education: Arriving at Democratic Aims and Experiences. J. Educ. Controv. 2007, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, M.; Mourshed, M. How the World’s Best-Performing School Systems Come Out on Top; McKinsey & Company: Osaka, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- EESC. EESC Info. July 2013/6 Special Edition; Retrieve; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stronge, J.H.; Ward, T.J.; Grant, L.W. What Makes Good Teachers Good? A Cross-Case Analysis of the Connection Between Teacher Effectiveness and Student Achievement. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 62, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.; Baker, A.; Ehrich, J.F.; Woodcock, S.; Bokosmaty, S.; Howard, S.J.; Eady, M.J. Teacher Disposition Scale (TDS): Construction and psychometric validation. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2018, 44, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, R.D.; Dereshiwsky, M. Teacher Motivation Tied to Factors within the Organizational Readiness Assessment Model. Elements of Motivation/De-Motivation Related to Conditions within School District Organization; Eric Institute of Education Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1990.

- Peterson, M.F.; Ruiz-Quintanilla, S.A. Cultural Socialization as a Source of Intrinsic Work Motivation. Group Organ. Manag. 2003, 28, 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubdy, R.; Williams, M.; Burden, R.L. Psychology for Language Teachers. TESOL Q. 1999, 33, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, U. Teaching and Researching: Motivation. In Teaching and Researching Motivation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, P.W.; Watt, H.M. Current and future directions in teacher motivation research. In The Decade Ahead: Applications and Contexts of Motivation and Achievement; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; Volume 16, pp. 139–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Perceived Autonomy: Relations with Teacher Engagement, Job Satisfaction, and Emotional Exhaustion. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eekelen, I.M.; Vermunt, J.D.; Boshuizen, H.P.A. Exploring teachers’ will to learn. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Manus, P.; Ragab, M.; Arisha, A.; Mulhall, S. Review of factors influencing employees’ willingness to share knowledge. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM), Belfast, UK, 7–8 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. Organisational justice: The dynamics of fairness in the workplace. APA Handb. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 3, 271–327. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An introduction to the Five-Factor Model and its applications. J. Personal. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P. Personality Traits as Predictor of Leadership Effectiveness among IT Professionals. Indian J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2009, 6, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. Creating schools for the future, not the past for all students. Lead. Lead. 2012, 2012, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Measuring Corporate Social Performance: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purhonen, P. Interpersonal Communication Competence and Collaborative Interaction in SME Internationalization. Jyväskylä Stud. Humanit. 2012, 1, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Purhonen, P.; Valkonen, T. Measuring Interpersonal Communication Competence in SME internationalization. J. Intercult. Commun. 2013, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, L.; Almonkari, M. Teaching networking: An interpersonal communication competence perspective. In Voices of Pedagogical Development—Expanding, Enhancing and Exploring Higher Education Language Learning; Jalkanen, J., Jokinen, E., Taalas, P., Eds.; Research-publishing.net: Doubs, France, 2015; pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzembayeva, G.; Kuanyshbayeva, A.; Maydangalieva, Z.; Spulber, D. Fostering pre-service EFL teachers’ communicative competence through role-playing game. J. Educ. E-Learn. Res. 2023, 10, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugg, S.A. The Relationship Between Teacher Leadership and Student Achievement. Ph.D. Thesis, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY, USA, 2013. Volume 138. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.C.; Tsai, R.J.; Finger, G.; Chen, Y.Y.; Yeh, D. What drives a successful e-Learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 1183–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werts, C.E.; Linn, R.L.; Jöreskog, K.G. Intraclass Reliability Estimates: Testing Structural Assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Lacker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.B.; Burns, R.A. Business Research Methods and Statistics Using SPSS; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, M.M.C.; Flynn, M. Determinants of students’ quality of school life: A path model. Learn. Environ. Res. 2002, 5, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Luchok, K.; Dozier, J. College students’ satisfaction and sense of belonging: Differences between underrepresented groups and the majority groups. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, U.; Çelik, E. Examining the Factors Contributing to Students’ Life Satisfaction. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2014, 14, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Qiu, Y. The Influence of University Teacher Leadership on Student Learning Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Teacher-student Interaction. In Proceedings of the Conference: ICIEI 2021: 2021 The 6th International Conference on Information and Education Innovations, Belgrade, Serbia, 16–18 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dilag, R.Y.L. The Role of Counselling Guidance on Student Learning Motivation. J. Asian Multicult. Res. Educ. Study 2023, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.S. Teacher leader. Phi Delta Kappan 2001, 82, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, M.C.P.; Ligaya, M.A.D. Students’ Performance in English: Effects of Teachers’ Leadership Behavior and Students’ Motivation. J. Educ. Learn. (EduLearn) 2025, 19, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzimińska, M.; Fijałkowska, J.; Sułkowski, Ł. Trust-Based Quality Culture Conceptual Model for Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, A. Caring teachers: The key to student learning. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2007, 43, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, N.C. Factors affecting student satisfaction with higher education service quality in Vietnam. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Wang, X.; Zhu, B. Exploring the Predictors of Satisfaction in a Blended Learning Course: Investigating the Role of Interaction and Self-Efficacy. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 29–31 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zee, M.; Koomen, H.M.Y. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Its Effects on Classroom Processes, Student Academic Adjustment, and Teacher Well-Being: A Synthesis of 40 Years of Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).