Abstract

The present study particularly aims to probe the quadratic effects of the combined and individual sovereign environmental, social, and governance (ESG) activities on the banking sector’s profitability. Furthermore, we attempt to shed light on the channels through which sovereign ESG practices impact the banking sector’s profitability. Unlike the vast majority of prior works that investigated the sustainability practice–firms’ profitability nexus from the firm level, this study originally probes this relationship from the country level by considering the sovereign ESG sustainability activities. To attain this purpose, we focus on banking sectors operating in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies and employ the panel-fixed effects and panel-corrected standard errors approaches between 2000 and 2022. Remarkably, the findings uncover that the nexus between combined sovereign ESG and profitability is a non-linear and inversed U-shape (concave), implying that investing in sovereign ESG enhances the banking sector’s profitability. However, after exceeding an inflection point (0.349), its effect turns out to be negative and it develops into activities of destruction. Furthermore, the findings underscore that the association between individual sovereign environmental responsibility and the banking sector’s profitability is a non-linear U-shape (convex), while an inversed U-shaped (concave) nexus is uncovered for the individual sovereign social and governance activities. Moreover, the significant non-linear inverted U-shape for the combined sovereign ESG–stability nexus corroborates that financial stability is a channel through which sovereign ESG significantly impacts profitability.

1. Introduction

Maintaining the stability and profitability of the banking sector is an important concern for policymakers for stimulating investments and improving economic development [1]. Prior works have also highlighted that having a more stable and profitable banking system has an important role in raising the strength of the financial system and sustainable development [2]. Because of the importance of the banking sector, several works have endeavored to probe the determinants that considerably cause a rise or decline in profitability. Comprehending the drivers of the banking sector’s profitability has a significant role in preventing bank failure and helping accelerate economic growth.

By studying the prior works, the traditional drivers can be classified into banking sector-specific and country and global level. For the internal factors, past works revealed that bank size [3,4], asset quality [5,6], capital adequacy [7], liquidity [8,9], inefficiency [10,11], bank ownership [12,13], and competition [14] are the significant factors which impact a bank’s profitability. Furthermore, for the external factors, previous works highlighted that inflation [10,15], GDP growth [16,17], financial market development [14,18], governance [14], and global risk [19] are examples of factors which significantly affect a bank’s profitability.

Focusing on increasing the threat of ESG risks, ESG activities have been increasing in importance and firms are actively implementing ESG principles into their operations to tackle global concerns and attain sustainable systems. Involvement in ESG practices could act as a governance framework and could be valuable to stakeholders. In particular, it is essential for banks to be engaged in ESG practices and more involvement in ESG activities by banks could accelerate attaining sustainable development. Empirically, several works have found that involvement in ESG activities could significantly impact firms’ profitability. In the literature, two primary stakeholder and trade-off theories exist to describe the impact of ESG on financial performance. Based on the stakeholder theory [20], a company has an ethical responsibility to maximize the value of stakeholders, and the linkage between ESG and financial performance is predicted to be positive. However, the trade-off theory predicts a negative association between ESG and financial performance and argues that ESG activity is a possibly inefficient use of resources and firms incur higher costs by involving ESG activities. In this vein, several works support the stakeholder theory by finding the positive nexus between banks’ profitability and corporate governance performance [21,22], environmental performance [23], and social performance [24,25]. Meanwhile, studies by [26,27] showed that ESG practices negatively affect the profitability of banks, supporting the trade-off theory.

What about the role of sovereign ESG in determining the banking sectors’ profitability and which factors positively and negatively impact profitability? Although the extant literature has extensively probed the effect of corporate ESG on companies, there are still significant gaps in studying the impact of sovereign ESG on the profitability of financial firms. For instance, the works by [19,28] uncovered that in environments with higher governance practice scores (e.g., increasing political stability and increasing regulatory quality), financial companies are more profitable than their counterparts. Ref. [29] showed that decreasing a country’s governance responsibility (e.g., rising corruption) adversely affects banks’ profitability and stability. Ref. [30] uncovered that lower involvement of countries in environmental responsibility (causing to rise in natural disasters) adversely impacts the profitability of banks.

More specifically, unlike corporate ESG studies, limited works have been found focusing on sovereign ESG on the banking sector’s profitability, particularly in the framework of GCC markets. Following a year of economic concern, GCC economies experienced a rapid economic recovery after COVID-19 and are estimated to return to a cumulative growth of 2.2% in 2021. Especially, the GCC is predicted to grow by 2.5% in 2023 and 3.2% in 2024, respectively. In the report by the [25], the economic growth is expected to be 2.7% for Bahrain, 1.3% in Kuwait, 1.5% in Oman, 3.3% in Qatar, 2.2% in Saudi Arabia, and 2.8% in the UAE in 2023. Based on the World Bank Data Bank (2000–2022), the banking sectors in GCC economies have some particular characteristics. As demonstrated in Table 1, the bank non-performing loan (NPL) ratio (% gross loans) was the highest in the UAE with a mean of 7.702, while Saudi Arabia had the lowest credit risk with a mean of 3.142. Likewise, the bank regulatory capital ratio (% risk-weighted assets) was the highest in Saudi Arabia with a mean of 19.111, while Oman had the lowest ratio with a mean of 16.285. Additionally, Table 1 reveals the banking sector in Oman had the highest inefficiency (proxied by the bank cost ratio (% income)) with a mean of 47.119, while the UAE had the most diversified (proxied by bank noninterest income ratio (% total income)) banking sector with a mean of 36.841, respectively.

Table 1.

Average banking sector ratios in GCC countries (2000–2022).

Moreover, Table 1 reveals that the banking sector had the lowest credit risk in Saudi Arabia, the lowest inefficiency and income diversification in Qatar, the lowest bank deposits in Saudi Arabia, and the lowest stability (Z-score) in Bahrain compared to other GCC economies. According to the World Bank Data Bank (2000–2022), the GCC countries had relatively weak sovereign ESG performance with a mean of 0.132 and were less likely to be engaged in environmental, social, and governance activities. In countries with weak ESG responsibilities performance, the financial system is relatively less stable, borrowing costs are comparatively higher, market friction distortions are relatively higher, and ultimately corporate ESG ranks are relatively lower (e.g., [31,32]). Therefore, the banking sector in GCC countries is an interesting case for study and understanding the effect of sovereign ESG as well as other traditional determinants on banking sectors’ profitability is essential.

In addition, there are no empirical works that deeply investigated the impacts of individual sovereign ESG activities on the banking sector’s profitability. In the literature, some works only explored the individual sustainability practices–profitability nexus from the firm level, and their findings highlighted that environmental, social, and governance have a mixed effect on firms’ profitability. Moreover, there is a scarcity of literature examining the channels through which sovereign ESG activities impact the banking sector’s profitability. Overall, there is a scarcity of literature probing the effect of sovereign ESG on profitability, particularly for banking sectors operating in the Arab markets. Hence, the present work aims to fill the gap by answering the subsequent research questions in the framework of banking sectors in GCC markets: (i) How does the combined sovereign ESG impact profitability? (ii) How do individual sovereign environmental, social, and governance activities impact profitability? (iii) What are the channels through which sovereign ESG impacts profitability?

This study contributes from several aspects. First, this study contributes by investigating especially the impact of sovereign ESG as well as the conventional determinants on the profitability of banking sectors in GCC countries between 2000 and 2022. The sovereign ESG score computes a country’s ESG performance calculated based on 17 key sustainability themes covering environmental, social, and governance classifications. Second, another contribution of this work is to test the effects of individual sovereign ESG on the banking sector’s profitability and delve into whether the banking sector’s NPLs and stability are the significant channels. Third, despite the large number of past studies in this field, we probe the non-linear nexus between the combined and individual sovereign ESG and profitability using the panel-fixed effects and panel-corrected standard errors methodologies. Recently, the works by [33,34] uncovered that there is a non-linear nexus between ESG and corporate performance. Fourth, unlike prior works that focused on banks in the U.S. [35], the EU [36], and the MENA and Turkey [34], this study contributes by selecting banking sectors operating in GCC economies.

Overall, the findings alert policymakers to provide useful guidelines when considering their ESG investments due to the non-linear inverted U-shaped association between sovereign ESG and the banking sector’s profitability. This implies that the policies for investing in sovereign ESG should be designed by finding an optimal level and through a balanced approach to achieve the country’s sustainability objectives and avoid the banking sectors’ profitability and stability concerns. Furthermore, the findings imply that policymakers consider the presence of the non-linearity nexus between the individual sovereign ESG and the banking sector’s profitability and prepare effective regulations and strategies for balancing between achieving environmental, social, and governance sustainability and maintaining the banking sector’s profitability. Moreover, the empirical findings indicate that policymakers should be focused on the significant role of traditional factors in improving the banking sectors’ profitability in the GCC economies.

The rest of the work is structured as follows. Section 2 reveals a literature review. Section 3 is the hypothesis development. Section 4 explains the data, models, and methods. In Section 5 and Section 6, empirical findings and robustness checks are presented. Section 7 provides the paper’s conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate ESG Performance

Numerous scholars have considerably probed the effect of corporate ESG activities on financial firms’ performance. For instance, the works by [21,37,38] argued that a rise in corporate governance performance is linked with curbing the expropriation of bank resources and increasing bank efficiency. Ref. [39] documented that increasing corporate social responsibility helps improve banks’ images and increase banks’ performances in India. Ref. [40] uncovered that there is a positive nexus between corporate ESG and financial performance in 90% of performed works. Ref. [41] uncovered that environmental disclosures by firms in the U.K. increase market values. Ref. [42] showed that high ESG performance is related to a modest decline in risk-taking for banks that are low or high risk-takers. The authors also revealed that higher ESG scores are linked with a decline in bank value. Ref. [43] documented that a rise in a bank’s corporate governance performance is adversely associated with a firm’s financial performance. Ref. [44] indicated that companies with higher ESG performance have a lower cost of borrowing in EU economies. Ref. [45] uncovered that the European banks with more ESG practices experience less instability during the financial distress period and this stabilizing impact is more prominent for banks with higher ESG ratings. Ref. [23] revealed that higher environmental performance of banks is associated with higher banks’ performance. Ref. [46] found that ESG practices positively affect Chinese firms’ financial performance.

In recent works, ref. [47] revealed that corporate environmental performance is adversely linked with the stability of banks in 74 countries but corporate social performance has no effect. Ref. [26] showed that corporate social responsibility leads to a decrease in banks’ performance. Ref. [48] highlighted that banks, by being involved in environmental activities, are less likely to give loans to carbon emission enterprises, leading to an effect on the bank’s performance. Ref. [49] uncovered that higher corporate ESG performance is linked with a greater size of bank loans, a lower possibility of collateral needs, and a lower cost of bank loans in China. Ref. [50] found that higher ESG ranks decrease banks’ operational risk. Ref. [51] also showed that banks’ ESG ratings are negatively linked with their credit risk. The authors argued that banks with high ESG activities carefully screen their borrowers and also monitor the use of loans, leading to decreasing NPLs (default risk). Ref. [52] documented that firms’ environmental and governance practices are negatively linked with profitability, though the social aspect has an insignificant effect. Overall, past works have highlighted that a better ESG performance is linked with lower systematic risk [53,54], idiosyncratic risk [55], and credit risk [56]. Additionally, a better ESG leads to a lesser borrowing cost [57], easier access to funds, and higher financial flexibility [58].

2.2. Sovereign ESG Performance

While corporate ESG performance has significant impacts, numerous studies underscored that the degree of corporate ESG performance significantly depends on sovereign ESG ratings. In other words, when sovereign ESG performance is higher, the corporate ESG score is greater and vice versa. For instance, ref. [59] documented that corporate social performance is significantly linked with sovereign governance and social activities performance (e.g., political stability, labor, and education). Ref. [60] by examining the link between the strength of country-level institutions and the extent of corporate social responsibility disclosures of firms in 21 countries, uncovered that there is a significant positive nexus between sovereign governance score and corporate social responsibility. Ref. [61] found that corporate social performance scores are high in countries with high social and governance ratings (e.g., high income-per-capita, strong political rights), and the country factors are much more essential than firms’ characteristics in describing the changes in corporate social performance ratings. Refs. [62,63] argued that the corporate social responsibility and performance nexus are likely to be impacted by a country’s ESG performance (e.g., institutional quality). Remarkably, ref. [26] underscored that sovereign governance performance has a substantial role in lessening the negative effect of corporate social responsibility on banks’ performance.

Due to the importance of sovereign ESG performance, a strand of the literature has been studied herein to probe the effect of countries’ ESG ranks on both macro and micro levels. Countries’ practices towards ESG aspects could be significant for sustaining a favorable investment climate. The prior works highlighted that the higher involvement of countries in improving ESG ranks leads to increasing the stability of the financial system and eventually triggering economic prosperity. Ref. [64] by focusing on 23 OECD economies during the 2007 to 2012 period documented that external financing costs are associated with sovereign ESG ratings and the borrowing costs in high ESG ranks countries are lower. Their findings showed that ESG ratings significantly reduce government bond spreads. Refs. [31,32] also revealed that decreasing sovereign governance responsibility performance (e.g., increasing political instability, increasing corruption, decreasing government effectiveness, decreasing voice and accountability) leads to rising market friction distortions, increasing the complexity of the business environment and decreasing the economy growth.

Apart from the macro level, past works have corroborated that sovereign ESG performance has significant impacts on firms’ policy decisions and behavior. For instance, refs. [32,65] uncovered that sovereign ESG significantly impacts firm-level investment decisions in both Pakistan and the U.K., respectively. Ref. [32] also documented that in countries with better governance responsibility performance (e.g., decreasing corruption, increasing government effectiveness, improving voice and accountability), firms are more likely to exploit profitable investment opportunities through either internal funds or external financing. As previously discussed, in high sovereign ESG ranks, borrowing costs are cheaper and firms have easier access to external funds. Nevertheless, a decrease in the performance of environmental (e.g., increasing climate policy uncertainty) and social (e.g., increasing migration policy uncertainty) aspects adversely affects corporate investment.

2.3. Individual Sovereign ESG Performance

2.3.1. Sovereign Governance Performance

More specifically, several works have endeavored to probe the effect of individual sovereign ESG aspects on firms. The prior works have concluded that the performance of environmental, social, and governance aspects could be an essential factor in triggering the risk-taking, stability, and performance of companies. For example, the works by [66,67] documented that firm executives prefer to make risky investments in economies with low performance of governance activities. The works by [19,28] also revealed that in environments with higher governance practice scores (e.g., increasing political stability, strengthening the rule of law), financial companies are more profitable than their counterparts. Ref. [68] documented that a low performance of countries toward governance practices (e.g., rising political instability) significantly triggers risk-taking behavior in the banking sector worldwide. Ref. [69] highlighted that a higher sovereign governance performance (e.g., decreasing corruption, increasing government effectiveness, strengthening legal systems) is associated with banks’ higher capital ratios in Arab markets. Furthermore, Ref. [70] revealed that a country’s governance responsibility performance could impact the bank’s credit risk, and the bank’s NPLs become lower by increasing governance scores in developing Asia. Similarly, ref. [71], using the quantile and fixed effects estimation methods, found that decreasing sovereign governance scores has a significant role in exacerbating banking sectors’ NPLs in BRICS between 2004 and 2021. Their findings also stressed that country governance has a significant moderator role, and by improving the quality of sovereign governance, the effect of country-specific risks on NPLs could be weakened. Ref. [72] documented that an increasing country’s governance responsibility performance (e.g., increasing government effectiveness) is inversely associated with banks’ NPLs but it positively impacts banks’ profitability. Furthermore, ref. [29] showed that a country’s decreasing governance responsibility (e.g., rising corruption) negatively affects banks’ profitability and stability.

2.3.2. Sovereign Social Performance

Additionally, some works revealed that sovereign social performance significantly affects banks globally. For instance, ref. [47] using a panel dataset of 473 banks in 74 economies showed that banks experience lower NPLs in countries engaging with high social responsibility performance scores. Refs. [72,73] uncovered that decreasing a country’s social responsibility performance (e.g., increasing unemployment rate) drives an increase in NPLs of banks in Emerging Asia and QISMUT plus Pakistan, Kuwait, and Bahrain, respectively. Ref. [72] also stressed that rising unemployment adversely impacted a bank’s profitability in Qatar, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Pakistan, Kuwait, and Bahrain between 2011 and 2018. However, ref. [74] revealed that increasing unemployment causes a rise in banks’ profitability in India.

2.3.3. Sovereign Environmental Performance

Moreover, several works argued that sovereign environmental performance impacts the financial stability of firms. For example, ref. [43] uncovered that firm performance is higher in economies with better environmental responsibility performance (e.g., reducing emissions). Ref. [75] documented that China’s carbon market will upsurge the level of corporate risk-taking of engaged enterprises. Ref. [30] also uncovered that weather-related natural disasters in the U.S. considerably reduce the financial stability of banks. The authors showed that rising natural disasters lead to increasingly higher probabilities of default risk, lower financial stability, and also lower profitability of banks.

3. Hypothesis Development: Sovereign ESG Activities and Banks’ Profitability

Based on the reviewed studies, sovereign ESG practices help reduce environmental, social, and governance-related risks and could be significantly impacted at both macro and micro levels. Additionally, the prior works revealed that there is a linkage between corporate ESG ratings and sovereign ESG performance, indicating that firms typically have higher ESG scores in countries with higher ESG ranks.

In the literature, two primary stakeholder and trade-off theories can be used to explain the ESG–financial performance nexus. Based on the stakeholder theory [20], a company has an ethical responsibility to maximize the value of stakeholders. While society and the environment are impacted by firm activities, being socially and environmentally aware is essential for the existence of the firm. Companies that are involved with ESG practices implicitly carry their inclination to fulfill all shareholders’ demands and prevent related costs involved with exact compliance with formal predetermined contracts. Thus, the stakeholder theory predicts that the ESG–financial performance linkage is positive and ESG practices could provide opportunities, competitive advantages, and innovation for firms instead of incurred costs [76,77].

Furthermore, the resource-based view and stewardship theory which are peripheral to stakeholder theory suggest similar expectations for the ESG–performance nexus. The resource-based view shows that investment in ESG activities leads to firms gaining a competitive edge by attaining further skills and improving ESG performance positively impacts financial performance [78]. Stewardship theory also identifies executives as the stewards of the company obligated to maximize the firm’s value. Managers are involved in ESG practices to reinforce relations among different stakeholders and enhance favorable business conditions, and improving ESG performance positively impacts firms’ value [79].

However, the trade-off theory predicts a negative nexus between ESG and financial performance and argues that ESG activity is a possibly inefficient use of resources. The trade-off view states that funds which are invested in ESG practices could be employed more effectively by the company. This view discusses that executives should raise the firm’s value and refrain from ESG activities to make the world a better place [80]. ESG is treated as an unreasonable pursuit and firms incur higher costs by involving ESG activities, leading to decreasing profits [81]. Ref. [82] argued that using resources to undertake social and environmental objectives (e.g., investment in pollution lessening, increasing employee wages, donations, and sponsorships for the community) upsurges costs and decreases competitive advantage and profitability. In the same vein, the agency theory offers a similar expectation to those of the trade-off theory and discusses that managers are involved in ESG practices to pursue their personal needs. Managers, by engaging in ESG practices, could build their reputation through media attention and publicity, leading them to obtain benefits directly at the expense of the company. Ref. [83] revealed that CEOs who are less entrenched are more likely to upsurge ESG practices compared with other CEOs.

Considering the above-mentioned theories, several studies attempted to describe the nexus between individual ESG activities and firms’ performance. Based on the resource-based view, prior works [84,85] have suggested that environmental improvements (e.g., pollution avoidance activities) can improve cost savings, increase competitive advantage, and enhance operational efficiency. Additionally, refs. [86,87] using the stakeholder- and resource-based theories argued that engaging in social activities allows firms to enhance their productivity and also market reputation and gain a differentiation advantage from competitors, the trust of investors, and the public’s confidence. Also, being involved in social activities leads to increasing a firms’ transparency, strengthening their market position, and ultimately raising long-term profitability [88,89]. In contrast, the prior studies using the agency theory expected that unnecessary charitable donations are an unjustified threat and lead to uncovering a negative linkage between firms’ social activity and financial performance [90,91].

Additionally, according to the trade-off theory, a negative link should be expected between environmental and social aspects and firm performance since the resource spending on these activities and its’ incurred costs outweigh the gained benefits, leading to weakening the competitive advantage and profitability [82]. Involvement in such activities leads to shifting the focus of firms’ executives towards practices that do not improve shareholder value [92]. Moreover, the agency theory view predicts that the linkage between governance practices and firm performance should be positive. Engaging with governance activities could enhance firm performance by improving reputation, raising supervision, lessening mismanagement, and ultimately decreasing agency problems [93].

Empirically, various works have endeavored to probe the impact of ESG on firms’ financial policies and behaviors. Although a higher sovereign ESG performance leads to enhanced financial market stability and averts managers from being involved in making risky decisions, there is a mixed answer about the impact of corporate ESG practices on firms’ profitability and the relationship between the two is still questionable. Ref. [94], by reviewing over 1000 published studies, showed that 58% of the studies found a positive association, 13% were neutral, 21% were mixed, and only 8% uncovered a negative association. Focusing on the positive effect, for instance, refs. [36,95] revealed that ESG activity positively impacts firms’ profitability. Ref. [35] revealed that the bank’s social practices positively impact profitability. Ref. [22] showed that profitability is higher in banks that are engaging with greater corporate governance activity. Ref. [96] showed that corporate social practices favorably impacted banks’ performance globally. Ref. [24] uncovered that corporate social performance has a favorable impact on the financial performance of the banking sector operating in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ref. [97] revealed that ESG positively impacts U.S. banks’ profitability. Ref. [98] uncovered that environmental and social performance favorably impact the profitability of banks but corporate governance performance does not significantly impact it. Ref. [27] also showed that social and environmental activities positively and negatively impact banks’ profitability in G8 economies, respectively, but banks’ governance responsibility has no significant impact. Some studies uncovered that a neutral nexus exists between corporate ESG activities and profitability [99,100].

In contrast, some works (e.g., [101]) uncovered that investment in ESG practices has a significant negative impact on firms’ profitability by increasing the opportunity costs of allocated capital. The works by [102,103] showed that profitability is adversely impacted by ESG activities since investment in ESG increases costs and also reduces firms’ resources because of financial allocations, human resources, and managerial inputs. While the prior works uncovered the linear association between ESG and profitability, numerous studies highlighted that the nexus between ESG and firms’ profitability is non-linear. For example, the works by [104,105] uncovered a U-shaped nexus, denoting that ESG activities in their initial stage adversely affect financial performance as costs outweigh the benefits, while at a later stage, the nexus reverts and becomes positive. Similarly, ref. [106] found a U-shaped nexus between governance responsibility and performance. Ref. [107] revealed that the nexus between ESG and firm efficiency is positive only at a moderate level of disclosure. Ref. [108] uncovered that after exceeding the threshold, ESG investment positively impacts firm performance. Nevertheless, ref. [33] uncovered that there is a non-linear inversed U-shape nexus between ESG and corporate performance. Ref. [109] revealed that there is a non-linear inversed U-shaped nexus between ESG and firm value. Similarly, ref. [34] showed a non-linear nexus between ESG and financial performance.

What about the nexus between sovereign ESG practices and the banking sector’s profitability in the emerging Arab markets? Although many studies were conducted to explore the corporate ESG–bank’s profitability nexus (e.g., [34,110]), limited studies have been initiated to probe the sovereign ESG–profitability nexus in general and for the banking sectors in GCC countries specifically. As discussed above, sovereign ESG practices decrease environmental, social, and governance-related risks and help companies benefit from greater country ESG activities. Moreover, a higher sovereign ESG performance leads to firms operating in greater stable financial markets with better access to capital. Furthermore, the banking sectors in developing GCC economies have tight profit margins and play an important role in boosting economic development. Additionally, such banks use considerably more resources and they are under more pressure to provide societal benefits. Hence, due to the importance of sovereign ESG performance and the scarcity of literature, it is essential to scrutinize the nexus between sovereign ESG activities and the banking sector’s profitability, particularly for emerging GCC economies.

Based on the theoretical explanations and empirical literature, we conjecture that the relationships between both the combined and separate sovereign ESG activities and the profitability of banking sectors are non-linear, either convex (U-curve) or concave (inverse U-curve).

H1.

There is a non-linear nexus between the combined sovereign ESG activities and the banking sector’s profitability.

H2.

There is a non-linear nexus between the individual sovereign environmental, social, and governance activities and the banking sector’s profitability.

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Data and Variable Explanation

This research selected the banking sectors operating in GCC countries including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates between 2000 and 2022. This study chose the factors based on past works, and their definitions, predicted signs, and sources are illustrated in Table 2. This work gathered the data for the dependent and independent factors from the World Bank and central banks. Likewise, following the prior works, the data for the global risk were collected from the policy uncertainty website.

Table 2.

Variable explanations.

Based on the World Bank, the combined sovereign ESG score (SESG) measures a country’s ESG performance. For the individual sovereign ESG, the sovereign environmental performance score (ENV) is measured by items classified as emissions and pollution, energy use and security, climate risk and resilience, food security, and natural capital endowment and management. For the social aspect, the sovereign social performance score (SOC) is measured by items classified as access to services, demography, education and skills, employment, health and nutrition, and poverty and inequality. In addition, the sovereign governance performance score (GOV) is measured by items classified in the economic environment, gender, government effectiveness, human rights, innovation, and also stability and rule of law. Overall, the higher score for combined and individual sovereign ESG scores indicates the performance oof more countries toward sustainability and tackling ESG risks.

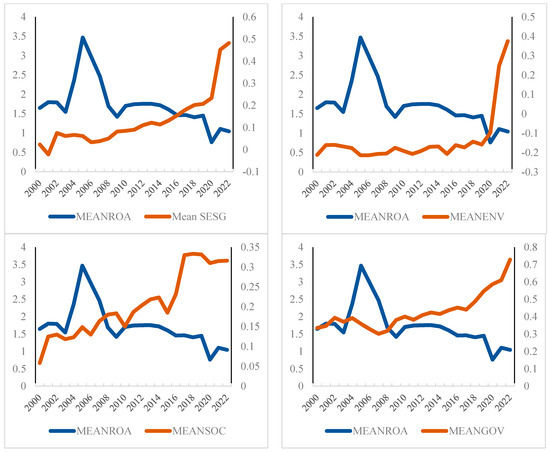

Figure 1 demonstrates the time series plot of combined and individual sovereign ESG performance scores and the banking sector’s profitability for the GCC countries between 2000 and 2022. As illustrated in Figure 1, there is a positive trend in the performance of SESG, ENV, SOC, and GOV, indicating that the GCC countries have substantially invested in ESG activities between 2000 and 2022. Despite the increases in sovereign ESG scores, Figure 1 reveals that the banking sector’s profitability increased up to a certain point, and then began to decrease. This could strengthen our conjecture that the sovereign ESG–banking sector’s profitability relationship is non-linear.

Figure 1.

Combined and individual sovereign ESG score and banking sector’s profitability.

4.2. Model and Methodology

This work foremost winsorized the variables for each year from the top and bottom 1% to prevent the outliers’ effect. In addition, we attempted to minimize the missing observations by checking the data from both the World Bank and central banks and also narrowing the period of the study. For estimating the equations, the present work applied the panel data method, causing a decline in heterogeneity and multicollinearity issues and also helping to upsurge the efficiency of estimations [111]. Additionally, following the works by [34,45], this work performs the pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) and the fixed effects methods. In choosing between the fixed effects and random effects, this study applied the Hausman test. Performing the fixed effects method helps control for all time-invariant disparities between the individuals and stops the estimated coefficients from being biased due to omitted time-invariant characteristics. Further, the fixed effects method could control unobserved heterogeneity [43]. Moreover, the panel-corrected standard error (PCSE) method is also applied to estimate the equations. As discussed by [112,113], the PCSE estimate is robust to unit heteroskedasticity and possible contemporaneous correlation. This work also used the lagged combined and individual sovereign ESG in the estimating models to alleviate the endogeneity problems [43,114]. It is noteworthy that we avoided using dynamic panel data estimation methods in the current work since the lagged dependent factor was excluded in the estimation models and the necessary dynamic condition (i = 6 < t = 23) was violated.

We used Equation (1) to test the effect of combined sovereign ESG performance on the banking sector’s profitability (H1). Additionally, in probing the effect of individual sovereign ESG performance on the banking sector’s profitability (H2), we used Equations (2)–(4) separately due to multicollinearity issues between the environmental, social, and governance aspects.

where i,t denotes country and time, correspondingly. εi,t is an independent error term. ROA is the banking sector’s profitability, C/TA is the capital adequacy, Ln (TA) is the bank size, OC/TA is the inefficiency, CONC is the competition, SESG is the sovereign ESG performance score, ENV is the sovereign environmental performance score, SOC is the sovereign social performance score, GOV is the sovereign governance performance score, SMC/GDP is the financial market development, INF is the inflation, and GR is the global risk.

4.3. Explanatory Variables

Consistent with the prior works, the present work selects the below determinants and hypothesizes the expected signs.

4.3.1. Banking Sector-Specific Factors

Capital Adequacy

This work selects capital adequacy, which is calculated by bank capital to total assets ratio (C/TA) and is expected to impact the banking sector’s profitability positively or negatively. Several works showed a positive nexus indicating that well-capitalized banks have higher profitability due to lesser demand for external funds (e.g., [7,13]. However, based on the risk–return trade-off, some works found a negative nexus, explaining that banks with greater capital have lower profitability because of the lesser leverage ratios and riskiness (e.g., [13,115]).

Bank Size

This study selects bank size, which is calculated by the natural logarithm of total assets (Ln (TA)) and is likely to impact the banking sector’s profitability positively or negatively. Several works showed a positive nexus, indicating that banks with larger sizes have higher profitability due to loan diversification and economies of scale (e.g., [4]). Nevertheless, some works (e.g., [116]) found a negative nexus.

Inefficiency

This study selects inefficiency, which is calculated by bank overhead costs to total assets (OC/TA) and is expected to impact the banking sector’s profitability positively or negatively. Several works [11] showed a negative nexus, implying that banks with higher inefficacy have lower profitability. Ref. [10] discussed that banks’ profitability is higher in well-managed banks since they could reduce operating costs. However, the work by [117] revealed that operating expenses positively impact banks’ profitability.

Competition

This study selects competition, which is calculated by the assets of the three largest banks to total commercial banking assets ratio (CONC) and is expected to impact the banking sector’s profitability positively or negatively. Following the structure-conduct performance (SCP) and Efficient-Structure (ES) hypotheses, a positive nexus between competition and profitability is expected. Some works supported the SCP hypothesis (e.g., [118,119]), while other works (e.g., [120,121]) confirmed the ES hypothesis. Empirically, some works ([10,122]) uncovered that concentration positively impacts profitability, though some works (e.g., [14]) found the opposite effect.

4.3.2. Country and Global Level Factors

Financial Market Development

This study selects financial market development, which is calculated by stock market capitalization to GDP ratio (SMC/GDP) and is expected to impact the banking sector’s profitability positively or negatively. Empirical works underscored that the financial structure significantly affects banks’ profitability either positively (e.g., [123]) or negatively (e.g., [18]).

Inflation

This study selects inflation, which is calculated by the annual inflation rate (INF) and is expected to impact the banking sector’s profitability positively or negatively. Based on argument by prior works, inflation can favorably impact banks’ profitability if inflation is envisaged and vice versa. Empirically, several works revealed either a positive nexus (e.g., [17]) or a negative relation (e.g., [14,15]).

Global Risk

This study selects global risk, which is calculated by the annual global economic policy uncertainty index (GR) and is expected to impact the banking sector’s profitability negatively. According to the prior works, a rise in economic policy uncertainty adversely affects profitability by decreasing assets’ return, increasing future cash flow volatility, deferring investments, and increasing borrowing costs [124]. Likewise, firms may upsurge cash reserves as a buffer against external shocks, which ultimately reduce profitability (e.g., [125,126]).

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Univariate Analysis

Table 3 illustrates the descriptive statistics using factors for each country and the GCC between 2000 and 2022. Panel (A) implies that Saudi Arabia and Qatar with a median of 2.021 and 2.106 have the highest profitability (ROA), while Bahrain and Kuwait with a median of 1.224 and 1.302 have the lowest profitability, correspondingly. Additionally, Bahrain with a median of 18.319, Oman with a median of 1.994, and Qatar with a median of 90.972 have the highest capital adequacy (C/TA), inefficiency (OC/TA), and competition (CONC), respectively. Furthermore, Panel (B) reveals that Saudi Arabia and the UAE with a median of 0.050 and 0.060 have the lowest sovereign ESG (SESG) performance scores, while Bahrain and Kuwait with a median of 0.12 have the highest SESG performance scores, correspondingly. Also, it shows Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar with a median of −2.00 have the lowest sovereign environmental performance (ENV) scores, whereas the UAE with a median of −0.130 has the highest ENV score. Likewise, Panel (B) reveals that Bahrain with a median of 0.270 and Oman with a median of 0.440 have the highest sovereign social (SOC) and governance (GOV) performance scores, respectively. This is while the UAE and Qatar with a median of 0.030 and 0.340 have the lowest SOC and GOV scores, correspondingly. Moreover, Panel (C) highlights that Kuwait with a median of 105.430 and 3.057 has the most developed financial market (SMC/GDP) and inflationary (INF) environment, respectively. Further, Panel (C) shows the mean (median) of global risk is 142.828 (121.324), denoting a high uncertainty at the global level in the period of work. Remarkably, the descriptive summary of the complete sample is presented in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics (2000–2022).

Table 4 illustrates the correlation matrix for the factors used. As shown, except for ENV, SOC, and GOV, the correlations among the factors are not considerably high, suggesting that it is likely to incorporate the factors in the same equation.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix.

Before estimating equations, we performed the Granger causality to detect the direction among the variables. As presented in Table 5, the causality runs from C/TA, Ln (TA), OC/TA, CONC, SESG, ENV, SOC, GOV, SMC/GDP, INF, and GR to ROA. This implies that we are less likely to observe the reverse direction among the factors and the estimated equations are not impacted by the endogeneity problem.

Table 5.

Granger causality test.

5.2. Multivariate Analysis

Table 6 presents the results of Equation (1) using the pooled OLS, fixed effects, and panel-corrected standard error methods. For the banking sector-level variables, Table 6 reveals that capital adequacy (C/TA) positively impacts the banking sector’s profitability. This supports the prior works (e.g., [73]) and indicates that banks with a higher C/TA have higher profitability. Additionally, the findings uncovered that bank size (Ln (TA)) positively impacts profitability, which supports the prior works (e.g., [4,127]). Likewise, the findings highlight that the coefficients of inefficiency (OC/TA), and competition (CONC) are negative and statistically significant, indicating that banks with higher inefficiency and competition are less profitable. This finding supports the past works, which revealed that a rise in inefficiency (e.g., [10,11]) and competition (e.g., [14,128]) reduce a bank’s profitability.

Table 6.

The impact of the combined sovereign ESG performance on the banking sector’s profitability.

Considering the country-level factors, the coefficients of SESG and SESG2 are statistically significant but with different signs. Although SESG positively impacts the banking sector’s profitability, SESG2 has a significant negative impact, indicating that the nexus between SESG and profitability is non-linear and an inverse U-shape (concave). This means that investing in SESG enhances profitability. However, after exceeding a turning point, its effect turns out to be negative and it becomes an activity of destruction. The findings confirm the first hypothesis (H1) and also support the work by [34], which uncovered the concave nexus between ESG and financial performance. However, this finding is contradicted by the works of [106,129], which revealed a U-shape and positive nexus between ESG and performance, correspondingly.

Furthermore, the findings show that the coefficient of financial market development (SMC/GDP) is positive and significant, implying that a higher development of financial markets leads to an increase in a bank’s profitability. Unlike some past works that uncovered a negative nexus (e.g., [18]), this finding corroborates the study by [123]. Additionally, the findings support past works (e.g., [19]) and underscore that inflation (INF) positively impacts profitability. Table 6 also reveals that the coefficient of global risk (GR) is negative and significant, suggesting that a rise in GR has a negative spill-over effect on the banking sector’s profitability in GCC countries. This finding confirms past works (e.g., [126]) and explains that a rise in GR may cause an upsurge in future cash flow instability, defer valuable investment, and increase borrowing costs, which ultimately decrease the assets’ return and profitability.

Table 7 reveals the results of Equations (2)–(4) using the fixed effects with the cluster-robust standard error approach. Specifically, Table 7 reveals the impacts of the individual sovereign ESG performance on the banking sector’s profitability by considering the control factors. The findings highlight that there is a non-linear nexus between ENV, SOC, and GOV and the banking sector’s profitability in GCC economies, confirming the past works (e.g., [106,130]). Additionally, the findings underscore that, unlike the U-shaped (convex) nexus between the ENV and the banking sector’s profitability, there is an inversed U-shaped (concave) nexus between SOC and the GOV with the banking sector’s profitability, supporting the second hypothesis (H2). The work by [34] also showed that there is a concave nexus between SOC and GOV with profitability, and excessive investments in social and governance aspects have a detrimental effect on profitability. However, the results are contradicted by some past works (e.g., [98,131]), which uncovered a positive nexus between ENV and profitability. Further, the findings are not supported by the work by [33], which did not show an inverted-U-shaped nexus between GOV and performance.

Table 7.

The impact of the individual sovereign ESG performance on the banking sector’s profitability (2000–2022).

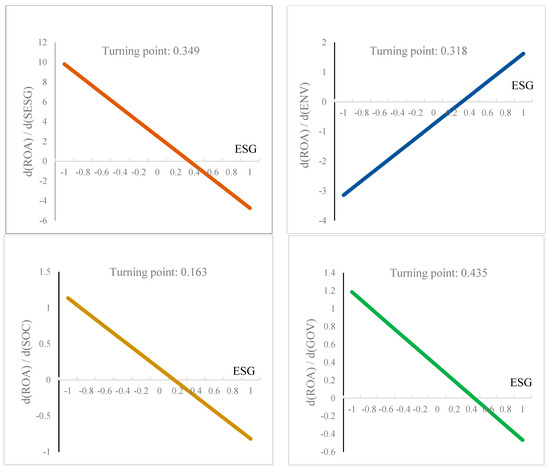

Figure 2 plots the marginal effect to better describe the relationship between the combined and individual sovereign ESG (SESG) and the banking sector’s profitability. As the work by [132] suggested, we plotted the conditional marginal effect (for instance, the marginal effect of SESG is measured by d(ROA)/d(SESG) = b1 + 2 × b2 × SESG) of SESG with their significance level. Based on the computing turning points and average values, Panel (A) shows that the turning point of SESG (0.349) is greater than its average value (0.132), denoting that the banking sector’s profitability is still reaping the benefits of investment in ESG. However, the marginal effect becomes negative after exceeding the turning point, indicating that excessive investments unfavorably impact profitability. Furthermore, as presented in the Panels (B, C, and D), the turning points for ENV, SOC, and GOV are 0.318, 0.163, and 0.435, respectively. Compared with the average values of −0.128 for ENV, 0.179 for SOC, and 0.419 for GOV, the banking sector’s profitability is still receiving the benefits of investment in ENV and GOV due to the larger values of thresholds. However, the incremental investments in SOC will decline profitability.

Figure 2.

Marginal effect plots for the combined and individual sovereign ESG at a 90% significance level.

We conducted a further analysis to investigate the channels through which sovereign ESG activities impact the banking sector’s profitability. To attain this objective, we focused on non-performing loans (NPLs) and the stability (Ln (Z)) of the banking sectors. Prior works (e.g., [45,51]) suggest that there is a significant nexus between NPLs and Ln (Z) with ESG performance. As revealed in Panel (A) of Table 8, there was no significant nexus found between the combined and individual sovereign ESG with NPLs, implying that the NPLs are not a channel through which sovereign ESG activities impact profitability. This finding is not in line with [51], which showed a significant negative linkage between ESG and bank’s NPLs.

Table 8.

The impacts of the combined and individual sovereign ESG on the banking sector’s non-performing loans and stability (2000–2022).

However, the findings in Panel (B) underscore that the stability of the banking sector is significantly affected by the SESG, though the nexus is non-linear and inverted U-shaped. This means that the stability of the banking sector still improves up to the turning point (0.289). However, after exceeding the threshold, incremental investment in SESG leads to a decrease in the stability of the banking sectors and eventually profitability. Additionally, the results reveal that except for the insignificant effect of ENV, investment in SOC and GOV significantly improves stability. The work by [45] revealed that the combined and individual ESG decreases bank instability during periods of financial concern. The findings also do not support the work by [133], which uncovered that there is a U-shaped nexus between firm engagement in the social aspect and bank stability.

6. Robustness Tests

The current research performs some robustness checks. First, we used an alternative proxy for measuring profitability by using ROE. Second, we estimated the equations by using the fixed effects model with Driscoll Kraay standard errors (1998) [134] and the panel-corrected standard errors. Using these methods helps to probe the reliability of the findings in the presence of cross-sectional dependence, heteroscedasticity, and autocorrelation (e.g., [32]). Table 9 (Panel (A)) presents the findings. Third, we estimated the baseline models by employing new measurements of “bank regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets (REQC/TA)” for measuring capital adequacy, “bank cost to income (C/I)” for computing inefficiency, “assets of five largest banks as a share of total commercial banking assets (5-Bank CONC)” for calculating competition, and “stock market total value traded to GDP (SMTV/GDP)” for measuring financial market development. We also added the global financial crisis dummy variable (GFC) (which is equal to one in 2008 and 2009 and zero otherwise) to capture the spillover effect of the financial crisis on the banking sector’s profitability in GCC countries. Table 9 (Panel (B)) illustrates the findings. Further, following the prior works by [43,114], we used the lagged combined and individual sovereign ESG in the estimating models to control the endogeneity problems. Lastly, we applied the CD test [135] to probe the presence of cross-sectional dependence in the estimation models.

Table 9.

Robustness checks I.

Overall, Table 9 reveals that the findings are similar, and combined sovereign ESG (SESG) has a non-linear inversed U-shape nexus between the banking sector’s profitability in GCC. The findings show that investing in the country’s ESG leads to increasing the banking sector’s profitability in GCC countries since the average of SESG (which is 0.132) is still less than the average of turning points (which is 0.251) obtained from the regressions.

Furthermore, we found similar results, shown in Table 7, for the individual sovereign ESG by replacing the dependent variable using a new proxy of ROE. As presented in Table 10, a non-linear relationship exists between ENV, SOC, and GOV with the bank’s profitability. Also, it reveals there is a U-shape nexus between ENV and ROE, while an inversed U-shape is found for SOC and GOV with ROE.

Table 10.

Robustness checks II.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implication

7.1. Conclusions

This work aims to probe the impact of the combined and individual sovereign ESG activities on the banking sector’s profitability. Further, the current work contributes by testing the channels through which SESG activities impact the banking sector’s profitability. To fill the gaps, we focus on banking sectors operating in GCC countries between 2000 and 2022. We postulate that the nexuses between both the combined and separate sovereign ESG practices and the banking sector’s profitability are non-linear, either convex or concave.

The findings suggest that the nexus between combined sovereign ESG and profitability is a non-linear and inversed U-shape (concave), implying that investing in sovereign ESG enhances the banking sector’s profitability. However, after exceeding an inflection point (0.349), its effect turns out to be negative and it becomes an activity of destruction. The findings confirm the first hypothesis (H1) and support the work by [34], which uncovered the concave nexus between ESG and financial performance. However, this finding is contradicted by the works of [106,129], which revealed a U-shape and positive nexus between ESG and performance, correspondingly. Additionally, unlike a non-linear U-shaped (convex) nexus for the individual sovereign environmental activity, the findings underscore that there is an inversed U-shaped (concave) linkage between the individual sovereign social and governance responsibilities with the banking sector’s profitability. The findings corroborate the second hypothesis (H2) and support the work by [34], which showed that there is a concave nexus between SOC and GOV with profitability. However, the results are contradicted by some past works (e.g., [98,131]), which uncovered a positive nexus between ENV and profitability. Further, the findings are not supported by the work by [33], which did not show an inverted-U-shaped nexus between GOV and performance.

Moreover, the significant non-linear inverted U-shape for the combined sovereign ESG–stability nexus confirms that financial stability is a channel through which sovereign ESG significantly affects the banking sector’s profitability. The findings also imply the essential role of capital adequacy, bank size, inefficiency, and competition banking sector-specific factors in shaping the banking sector’s profitability. The results also highlight that country- and global-level factors containing financial market development, inflation, and global risk significantly impact profitability, supporting the prior works (e.g., [123]). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is an original study that considers the importance of sustainability practices from the country level on firms’ profitability and the results significantly contribute to the related literature.

7.2. Implications

The findings have important policy implications. First, the statistically significant effect of sovereign ESG suggests that policymakers consider the essential role of sovereign ESG activities in enhancing the banking sector’s profitability. In addition, the existing non-linear inverted U-shaped association between sovereign ESG and the banking sector’s profitability alerts policymakers to provide useful guidelines when considering their ESG investments. Although engaging in ESG activities leads to achieving a sustainable environment, it leads to decreasing the banking sector’s profitability after excess investments, which ultimately deteriorates economic development. Hence, the policies for investing in sovereign ESG should be designed by finding an optimal level and through a balanced approach to achieve the country’s sustainability objectives and avoid the banking sectors’ profitability and stability concerns. Second, the findings of the individual sovereign ESG also suggest that policymakers consider the presence of the non-linearity relationship and formulate effective regulations and strategies for investment in environmental, social, and governance activities. Policymakers should be invested in ESG activities in a way to not decrease banking sectors’ profitability and so that the applied actions do not burden banks with profitability challenges. Overall, the findings recommend that policymakers design a framework to promote investment in sovereign ESG by safeguarding the profitability of the banking sectors and avoiding economic deterioration.

Third, the findings suggest that policymakers and bankers focus more on the important factors at the banking sector and country level which have a key role in the shaping the profitability of banking sectors in the GCC countries. Furthermore, they should pay more attention to curbing the adverse spillover impact of global risk on the banking sector’s profitability through diversifying loan portfolios and investments and setting a prudential risk framework for averting financial instability and ultimately improving profitability.

It would be useful for further studies to examine the components of sovereign ESG activities on the banking sector’s profitability. Additionally, it would be beneficial for further works to probe the interaction effects of sovereign ESG and control factors on the banking sector’s profitability. Likewise, further studies could investigate the impact of sovereign ESG on the banking sector’s profitability for other emerging and advanced economies. In addition, it would be useful for further studies to examine the effects of sovereign ESG on firms’ profitability operating in other industries to provide a more comprehensive picture. Moreover, further studies, by increasing the number of sample countries, can cover the methodological limitation of this study and capture the dynamic effect of sovereign ESG on firms’ profitability through the System or Difference-GMM methods. Future works could also probe this relationship by developing the estimation model of this study by adding more factors at the banking sector level like the liquidity ratio.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.A.; methodology, S.A.A.; software, S.A.A.; validation, S.A.A.; formal analysis, S.A.A.; investigation, S.A.A., C.S., E.A. and N.E.-B.; resources, S.A.A.; data curation, S.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.A., C.S., E.A. and N.E.-B.; writing—review and editing, S.A.A.; visualization, S.A.A.; supervision, S.A.A.; project administration, S.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the research guidelines approved by the Ethics Committees of the authors’ institutions.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of the entire sample (2000–2022).

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of the entire sample (2000–2022).

| Variables | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 1.745 | 1.599 | −0.923 | 3.984 | 0.776 |

| C/TA | 13.757 | 12.264 | 5.017 | 52.360 | 7.973 |

| Ln (TA) | 21.896 | 22.266 | 12.196 | 28.126 | 4.391 |

| OC/TA | 1.340 | 1.269 | 0.654 | 2.681 | 0.380 |

| CONC | 74.302 | 77.450 | 44.087 | 100.00 | 14.414 |

| SESG | 0.132 | 0.110 | −0.050 | 0.580 | 0.130 |

| ENV | −0.128 | −0.175 | −0.290 | 1.000 | 0.194 |

| SOC | 0.179 | 0.180 | −0.680 | 0.530 | 0.164 |

| GOV | 0.419 | 0.410 | −0.030 | 0.870 | 0.150 |

| SMC/GDP | 74.690 | 66.392 | 20.888 | 345.353 | 43.846 |

| INF | 2.548 | 2.190 | −4.863 | 15.050 | 3.218 |

| GR | 142.828 | 121.324 | 62.676 | 319.999 | 68.593 |

Note: Table A1 reveals the descriptive statistics of the entire sample between 2000 and 2022.

References

- Menicucci, E.; Paolucci, G. The determinants of bank profitability: Empirical evidence from European banking sector. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2016, 14, 86–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. Financial development and economic growth: Views and agenda. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- Athari, S.A. Domestic political risk, global economic policy uncertainty, and banks’ profitability: Evidence from Ukrainian banks. Post-Communist Econ. 2021, 33, 458–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, O.; Ashraf, M. Bank-specific and macroeconomic profitability determinants of Islamic banks: The case of different countries. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2012, 4, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; De Jonghe, O.; Schepens, G. Bank competition and stability: Cross-country heterogeneity. J. Financ. Intermediation 2013, 22, 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, D.S.; Zergaw, L.N. Bank specific, industry specific and macroeconomic determinants of bank profitability in Ethiopia. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ebenezer, O.O.; Omar, W.A.W.B.; Kamil, S. Bank specific and macroeconomic determinants of commercial bank profitability: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. Int. J. Financ. Bank. Stud. 2017, 6, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, J.; Molyneux, P.; Wilson, J.O. The profitability of European banks: A cross-sectional and dynamic panel analysis. Manch. Sch. 2004, 72, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P. Profitability of Vietnamese Banks Under Competitive Pressure. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2019, 55, 2004–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasoglou, P.P.; Brissimis, S.N.; Delis, M.D. Bank-Specific, Industry-Specific and Macroeconomic Determinants of Bank Profitability; Working Paper No. 25; Bank of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petria, N.; Capraru, B.; Ihnatov, I. Determinants of banks’ profitability: Evidence from EU 27 banking systems. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azofra, V.; Santamaría, M. Ownership, control, and pyramids in Spanish commercial banks. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A.; Wanzenried, G. Determinants of bank profitability before and during the crisis: Evidence from Switzerland. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2011, 21, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naceur, S.B.; Omran, M. The effects of bank regulations, competition, and financial reforms on banks’ performance. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2011, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naceur, S.B.; Kandil, M. The impact of capital requirements on banks’ cost of intermediation and performance: The case of Egypt. J. Econ. Bus. 2009, 61, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaqtari, F.A.; Al-Homaidi, E.A.; Tabash, M.I.; Farhan, N.H. The determinants of profitability of Indian commercial banks: A panel data approach. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 24, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Ponce, A. What determines the profitability of banks? Evidence from Spain. Account. Financ. 2013, 53, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Moore, T.; Liu, G. Does market structure matter on banks’ profitability and stability? Emerging vs. advanced economies. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 2920–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.A.; Bahreini, M. The impact of external governance and regulatory settings on the profitability of Islamic banks: Evidence from Arab markets. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 28, 2124–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited”. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, S.; Hassan, M.K.; Al Farooque, O.; Mobarek, A. The governance, risk-taking, and performance of Islamic banks. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2017, 51, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peni, E.; Vähämaa, S. Did good corporate governance improve bank performance during the financial crisis? J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2012, 41, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caby, J.; Ziane, Y.; Lamarque, E. The impact of climate change management on banks profitability. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siueia, T.T.; Wang, J.; Deladem, T.G. Corporate Social Responsibility and financial performance: A comparative study in the Sub-Saharan Africa banking sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- AlAjmi, J.; Buallay, A.; Saudagaran, S. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and banks’ performance: The role of economic performance and institutional quality. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2023, 50, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, O.; Cankaya, S. Examining the relationship between ESG scores and financial performance in banks: Evidence from G8 countries. Press Acad. Procedia 2021, 14, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassa, R.; Matoussi, H. Corporate governance of Islamic banks: A comparative study between GCC and Southeast Asia countries. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2014, 7, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, S.; Gulzar, M.; Afzal, M.; Farooq, M.U. The Role of Corruption, Transparency, and Regulations on Asian Banks’ Performance: An Empirical Analysis. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noth, F.; Schüwer, U. Natural disasters and bank stability: Evidence from the US financial system. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 119, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zhang, B. Political uncertainty and finance: A survey. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2019, 48, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Lau, C.K.M. Sovereign ESG and corporate investment: New insights from the United Kingdom. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, W.; Hassan, M.K.; Houston, R.; Karim, M.S. ESG activities and banking performance: International evidence from emerging economies. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2021, 70, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, R.; Nasrallah, N.; Alareeni, B. ESG and financial performance of banks in the MENAT region: Concavity–convexity patterns. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2023, 13, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.G.; Kohers, T. The link between corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the banking industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 35, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprio, G.; Laeven, L.; Levine, R. Governance and bank valuation. J. Financ. Intermediation 2007, 16, 584–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.; Ayumardani, A. The corporate governance efficiency and Islamic bank performance: An Indonesian evidence. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 13, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihari, S.C.; Pradhan, S. CSR and performance: The story of banks in India. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2011, 16, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Shaukat, A.; Tharyan, R. Environmental and social disclosures: Link with corporate financial performance. Br. Account. Rev. 2016, 48, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, C.; Thornton, J. Do ESG scores effect bank risk taking and value? Evidence from European banks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2286–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bătae, O.M.; Dragomir, V.D.; Feleagă, L. The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: A European study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Aboud, A.; Saleh, A. ESG practices and the cost of debt: Evidence from EU countries. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2021, 79, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, L.; Dreassi, A.; Girardone, C.; Piserà, S. Do ESG strategies enhance bank stability during financial turmoil? Evidence from Europe. Eur. J. Financ. 2022, 28, 1173–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, G. ESG disclosure and financial performance: Moderating role of ESG investors. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, K.; Disli, M.; Ng, A.; Dewandaru, G.; Nkoba, M.A. The impact of sustainable banking practices on bank stability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 178, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Ren, Y.; Tan, W.; Wu, H. Does carbon emission of firms matter for Bank loans decision? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 86, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Shi, B.; Song, Y.; Wu, H. ESG performance and loan contracting in an emerging market. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 78, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, S.; Goodell, J.W.; Mazzù, S.; Paltrinieri, A. Bank reputation and operational risk: The impact of ESG. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jin, J.; Nainar, K. Does ESG performance reduce banks’ nonperforming loans? Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Dagar, V.; Sohag, K.; Dagher, L.; Tanin, T.I. Good for the Planet, Good for the Wallet: The ESG Impact on Financial Performance in India. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 56, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Wang, H.; Kwok, C.C. Family control and corporate social responsibility. J. Bank. Financ. 2016, 73, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Qin, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.G. CSR and idiosyncratic risk: Evidence from ESG information disclosure. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, L.H.; Starks, L.; Zhu, Q. Climate Regulatory Risk and Corporate Bonds; No. w29994; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Poufinas, T.; Antonopoulos, A. ESG scores and cost of debt. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.F.; Shan, H. Corporate ESG profiles and banking relationships. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 3373–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 834–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, S.F.; De Villiers, C.; Jeter, D.C.; Naiker, V.; Van Staden, C.J. Are CSR disclosures value relevant? Cross-country evidence. Eur. Account. Rev. 2016, 25, 579–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Pan, C.H.; Statman, M. Why do countries matter so much in corporate social performance? J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Maso, L.D.; Liberatore, G.; Mazzi, F.; Terzani, S. Role of country-and firm-level determinants in environmental, social, and governance disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Liu, J.; Sheng, S.; Fang, H. Does eco-innovation lift firm value? The contingent role of institutions in emerging markets. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 1763–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crifo, P.; Diaye, M.A.; Oueghlissi, R. The effect of countries’ ESG ratings on their sovereign borrowing costs. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2017, 66, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Nasimi, A.N.; Nasimi, R.N. The uncertainty–investment relationship: Scrutinizing the role of firm size. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17, 2605–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, R.L.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Law and finance. J. Political Econ. 1998, 106, 1113–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, R.L.; Lopez-deSilanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Investor Protection: Origins, Consequences, and Reform; No. w7428; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Athari, S.A.; Irani, F. Does the country’s political and economic risks trigger risk-taking behavior in the banking sector: A new insight from regional study. J. Econ. Struct. 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.A. Examining the impacts of environmental characteristics on Shariah-based bank’s capital holdings: Role of country risk and governance quality. Econ. Financ. Lett. 2022, 9, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arham, N.; Salisi, M.S.; Mohammed, R.U.; Tuyon, J. Impact of macroeconomic cyclical indicators and country governance on bank non-performing loans in Emerging Asia. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2020, 10, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.A.; Saliba, C.; Khalife, D.; Salameh-Ayanian, M. The Role of Country Governance in Achieving the Banking Sector’s Sustainability in Vulnerable Environments: New Insight from Emerging Economies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapiyanova, K.; Faizulayev, A.; Ruzanov, R.; Ejdys, J.; Kulumbetova, D.; Elbadri, M. Does social and governmental responsibility matter for financial stability and bank profitability? Evidence from commercial and Islamic banks. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2023, 14, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A.; Wanzenried, G. The determinants of commercial banking profitability in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2014, 54, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Rakshit, D. Macroeconomic Factors Affecting the Profitability of Commercial Banks: A Case Study of Public Sector Banks in India. Asia-Pac. J. Manag. Res. Innov. 2023, 2319510X231181891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wu, N. Will the China’s carbon emissions market increase the risk-taking of its enterprises? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 77, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. A theoretical framework for monetary analysis. J. Political Econ. 1970, 78, 193–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galant, A.; Cadez, S. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance relationship: A review of measurement approaches. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2017, 30, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiraporn, P.; Chintrakarn, P. How do powerful CEOs view corporate social responsibility (CSR)? An empirical note. Econ. Lett. 2013, 119, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelisi, F.; Soana, M.G.; Schwizer, P. The determinants of reputational risk in the banking sector. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J. The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1518–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J.; Aracil, E. European banks’ reputation for corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangi, F.; Meles, A.; D’Angelo, E.; Daniele, L.M. Sustainable development and corporate governance in the financial system: Are environmentally friendly banks less risky? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 2010, 77, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Corporate governance and the cost of capital: An international study. Int. Rev. Financ. 2014, 14, 393–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. Bus. Ethics Q. 2002, 12, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Hasan, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder’s Value: An Event Study Analysis; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]