1. Introduction

Price promotion is one of the 4P marketing strategies. The American Marketing Association defines price promotion as a business strategy that conveys pricing information to customers and inspires them to make a purchase. Schiffman (2002) proposes in Consumer Behavior that price promotion is a sort of promotion approach, which is performed primarily by dropping the selling price of a product or brand for a specified duration with a particular marketing purpose [

1]. The subject of price promotion is the manufacturer or a participant in the distribution channel [

2]. Managers of various subjects decrease the price by devising various price promotion tactics, such as direct price reduction or bundling, in order to boost sales [

3,

4,

5].

As a product of contemporary commerce, the supermarket is the major channel for consumers to purchase daily necessities. Due to its formal management, positive reputation, low prices, trustworthy goods, and other characteristics, it has progressively taken up a larger share of China’s retail market since its inception there in the 1990s. However, in recent years, with the explosive growth of e-commerce, an increasing number of people have chosen to purchase online, which has had a significant impact on the conventional supermarket business [

6,

7]. Simultaneously, hypermarket chains from other countries have begun to join the Chinese market, causing Chinese local supermarkets to fail or incur losses [

8]. To cope with the fierce competition, supermarket chains in China use different promotional activities to improve consumer purchasing behavior. These promotional activities also play an important role in the sustainable development of offline retail. The managers of supermarkets usually split a year into multiple promotional seasons and select various product categories in each season.

Although price promotions are regarded as a crucial approach to improving business performance, it is necessary to note that they may not obtain similar outcomes since managers generally combine several promotional strategies [

9]. On the basis of observations and recordings, we observed that the length of several promotional seasons in chain stores varied from 3 to 20 days, including a broad variety of items and discounts. Various product combinations or promotion efforts throughout promotional periods might result in a performance discrepancy across supermarkets. It is normal for shops with extensive promotional periods or high discount levels to have lower revenue than retailers with occasional promotions or low discount levels. Therefore, the examination of the relationship between promotional strategies and business performance is of utmost importance.

Previous studies on the relationship between price promotions and consumer behavior have primarily concentrated on Western countries. Theoretical models have been broadly explored from the standpoint of the improvement of supermarket performance by three price promotion mechanisms—price competition [

10], intertemporal price discrimination [

11], and multi-product pricing effects [

12]. According to empirical analysis based on scanner data from the United States and Israel, price promotion is proven to be one of the most effective tactics for supermarkets to cope with competitive pressure and improve their performance [

13,

14,

15]. However, Chinese supermarkets are distinct from those in the West since Chinese consumers’ behaviors are different as they enjoy fresh food and do not like to hoard products. In China, the number of supermarkets gradually decreases from community or commercial centers to the periphery. The majority of supermarkets in urban are community stores, typically located in neighborhoods with convenient transportation and a large population density, as well as on main and secondary highways close to commercial areas. Supermarkets generally sell goods in small packages to meet Chinese consumers’ shopping habits. The disparities between supermarkets in China and the West may cause some differences in the conclusions obtained from studies based on the Chinese market and those in Western countries. It would be preferable to provide policy suggestions for emerging nations if the research was based on local Chinese data.

As price promotion strategies play an increasingly essential role in local supermarkets in China, Chinese academics have also investigated the relationship between promotional strategies and consumer behavior. However, there is still some dispute about what the study found. Some scholars have investigated the differences in consumers’ perceptions and behaviors in response to price promotion, arguing that promotions can enable consumers to obtain greater product value per unit cost, enabling them to choose promotional products and maximize utility in their purchase decisions [

16,

17], while other academics have found that the excessive use of discounts, gifts, and other promotional strategies generates promotional expectations among consumers, which diminishes the attractiveness of promotions and decreases consumer purchases [

18], thus resulting in poor supermarket performance.

According to a review of the existing literature, the effect of price promotions on the purchasing behavior of consumers is contested. This may be attributed to variations in results caused by factors such as promotion depth, promotion duration, and promotion area. In addition, this can be a result of the varying effects of price promotions on the purchasing behavior of consumers across categories. Furthermore, since there are relationships between substitution and complementarity among products, price promotions may further change these connections. As a result, it is vital to conduct a category-specific in-depth study in order to assess how price promotions affect supermarkets as a whole.

Additionally, the present study mostly considers promotion depth as an indication of price promotions when assessing the impact of price promotions on supermarket performance, disregarding the consequences of promotion breadth and duration. The results of single-item promotions versus multi-category synergistic promotions may differ widely according to the connection between items and transaction costs, and only measuring promotion depth may provide unpredictable results. Therefore, this research will concurrently investigate multiple characteristics of price promotions, including promotion depth, promotion breadth, and promotion duration.

In this study, to supplement previous research and further investigate the relationship between promotional strategy selection and consumer behavior in the Chinese market, we model the relationship using sales and pricing data for all goods in ten major stores of a leading regional supermarket chain in China and attempt to answer the following questions with an empirical model based on scanner data. Firstly, can price promotions encourage consumers to shop in supermarkets? Secondly, how can price promotions attract consumers to shop in supermarkets, and what are the theoretical mechanisms and actual effects? Thirdly, how does the adoption of promotional strategies affect the purchasing behavior of consumers regarding products with various category characteristics?

The remaining sections are organized as follows.

Section 2 summarizes the findings of prior research. In addition, a framework for theoretical analysis is offered in this part. In

Section 3, we describe the employed data, descriptive statistical analysis, and empirical model. The

Section 4 includes the empirical findings and analyses. In

Section 5, we compare and discuss the empirical results obtained in this study with the existing related literature. In

Section 6, we draw conclusions from the empirical study and offer the optimal price promotion strategy for Chinese supermarket managers.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

The theory of price competition suggests that formulating price promotion strategies for consumer groups with different price and information sensitivities can effectively enhance a company’s performance [

19]. In the market, some consumer groups exhibit high sensitivity to prices and are willing to fully grasp price information, tending to seek the lowest-priced products among different suppliers when making purchases. Therefore, when a significant proportion of consumers in the market are price- and information-sensitive, suppliers can capture the entirety of the market share by lowering prices, thus maximizing profits. The foundation of price competition models can be traced back to microeconomics research by Cook (2020) and Rosenthal (1980) [

10,

20], and it has been further developed by researchers such as Raju et al. (1990), Baye et al. (1992), Sinitsyn (2017), and Petkov (2018) [

21,

22,

23,

24].

The theory of multi-product pricing posits that supermarkets, as multi-product providers, can attract consumers and stimulate their consumption of other products by offering promotions on a small selection of items, thereby maximizing supermarket profits [

25,

26]. This model is derived from the loss leader pricing model, with Degraba (2006) introducing variations to target more profit-oriented customers [

27]. According to Degraba’s model, pricing turkey at a loss in supermarkets encourages consumers to purchase complementary products, not only offsetting the losses from the turkey promotion but also helping maximize overall profits. The aforementioned theoretical viewpoints have been tested and verified by Fader and Lodish (1990), Van Heerde et al. (2003), Shelegia (2012), and Li (2013) [

28,

29,

30,

31]. As this theory has evolved, researchers have found that consumers attracted by promotions may exceed their budgets, leading to increased spending and, consequently, supermarket profits [

32].

Supermarket price promotion activities employ intertemporal price discrimination theory to exploit consumer surplus and boost corporate revenue. Intertemporal price discrimination falls under the category of third-degree price discrimination, where firms separate consumers into different groups based on their sensitivity to time and price [

33,

34]. Consumers with higher time sensitivity and lower price sensitivity tend to make purchases during non-promotional periods, while those with lower time sensitivity but higher price sensitivity adopt a wait-and-see approach. The second group is willing to wait until the lowest prices appear before making purchases. Firms are inclined to use price promotion strategies to attract the second group of price-sensitive consumers after the first group has made their purchases, aiming to exploit consumer surplus and increase corporate profits [

35]. The class of models is primarily proposed by Conlisk et al. (1984), Sobel (1984), and Pesendorfer (2002) [

11,

13,

36]. Pesendorfer (2002) and Berck et al. (2008) applied different degrees of intertemporal price discrimination theory to validate it using product scanning data for tomato sauce and orange juice in the American food retail market, respectively [

13,

15].

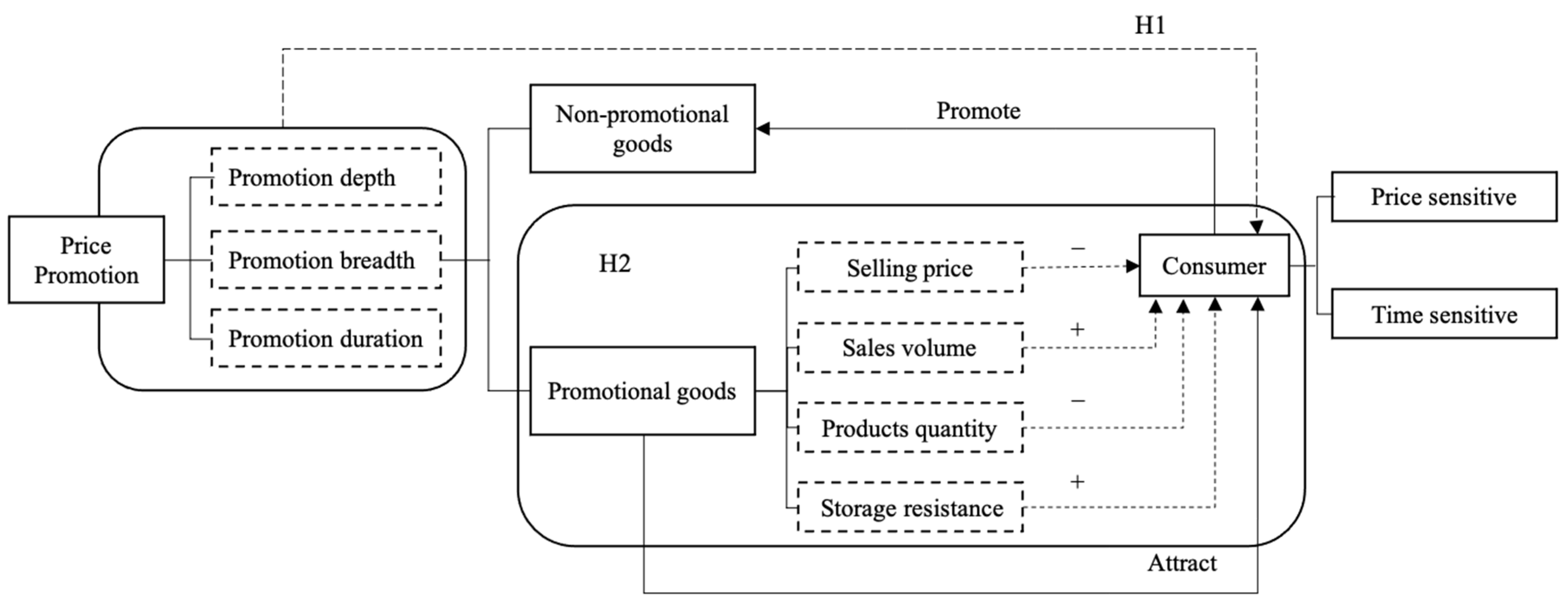

The theoretical framework of this study (

Figure 1) builds upon existing research and further decomposes the impact of price promotion characteristics and product attribute features on the purchasing behavior of consumers. In order to gain a larger market share, supermarkets temporarily alter prices through price promotions. Consumers incur shopping costs when shopping at supermarkets, including transportation costs, time costs, and transaction costs associated with purchasing goods. As the depth of price promotions increases, price-sensitive consumers perceive a reduction in total shopping costs due to the gradual decrease in transaction costs associated with purchasing goods. Consequently, the total utility increases. Therefore, the depth of promotions drives the sales of promotional items by influencing price-sensitive consumers, thereby improving performance. It should be emphasized that large comprehensive supermarkets offer a wide variety of products, and price promotion activities are often based on cross-product coordination. We assume that each consumer has a planned shopping basket, and compared to single-item promotions, cross-product promotions are more likely to reduce the amount spent on the planned shopping basket. Therefore, as the number of promoted items increases, the attractiveness to price-sensitive consumers increases, leading to a greater increase in the sales of promotional items. For the sales and consumption of promotional items, on the one hand, consumers’ purchases of promotional products may be used for storage or deferred consumption, shifting future consumption to the present, especially for products with a long shelf life and convenient storage. Price promotions often yield significant promotional effects, increasing current-period performance [

28]. On the other hand, Assunção and Meyer (1993) found that the inventory pressure resulting from the purchase of promotional products could lead to accelerated consumption by consumers [

37]. Therefore, the consumption growth brought about by promotions has a positive impact on supermarket performance.

Price promotions not only have a positive impact on the sales of promotional items but also promote the sales of non-promotional items to some extent. On the one hand, as the depth and breadth of promotions increase, supermarkets attract many price-sensitive consumers. Once these consumers enter the supermarket, the sunk costs associated with transportation and time from their place of origin to the supermarket become significant. Even if some planned items are not on promotion, consumers will hesitate to switch to another store to purchase them due to the additional costs of transportation and time. These higher switching costs confine consumers to the supermarket. On the other hand, with an increase in the number of promoted items, consumers need to spend more effort wandering around the supermarket to search for and identify promotional product information. During this process, they may also come across other non-promotional items, which may stimulate unplanned purchases by consumers. Furthermore, as the depth of promotions increases, consumers save more, and the increase in purchasing power may drive the sales of other products. Therefore, price promotion activities can boost sales across all product categories in the supermarket. Consequently, based on the analysis of the impact mechanism of price promotions on supermarket performance, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. As the promotion depth and breadth increase, more consumers are attracted to enter the supermarket and purchase non-promotional products along with promotional products, which increases purchase behavior.

Additionally, the impact of price promotions on the purchasing behavior of consumers varies across different product categories. Based on the price elasticity theory, if a product category lacks price elasticity, price promotions are unlikely to significantly increase sales. However, if a product category is characterized by price elasticity, price promotions can boost revenue through higher sales volumes with lower profit margins. The differences in product price elasticity are mainly attributed to factors such as product characteristics, functionality, and consumer demand for the product. Therefore, different product categories exhibit variations in the impact of price promotions on performance.

Furthermore, let us analyze the differences in the characteristics of product categories. First, when price promotions are applied to products with higher price levels, consumers, under the same promotional intensity, incur higher transaction costs. In situations with budget constraints, it seems easier for consumers to increase their purchases of lower-priced products because the impact on their budget is smaller. Consequently, price promotions have a more significant effect on products with lower price levels. Second, products with higher average sales levels perform better in terms of promotions. This is primarily because higher sales levels indicate a higher purchase frequency for the product, larger consumer demand, and faster consumption rates. Such products become more attractive to consumers through promotions, driving consumption. Third, product categories with a higher quantity of products perform less effectively in promotions. The numerous products within these categories increase the cost for consumers to search for promoted items, discouraging purchases by consumers with higher time costs. Additionally, a higher quantity of products within a category indicates higher market competition, resulting in more choices for consumers and higher decision-making costs, making it less favorable for consumer shopping. Fourth, products with longer shelf lives perform better in promotions. When there is available storage space, consumers can purchase these products in larger quantities and stock up, increasing current consumption for future use and consequently reducing the unit price of the product over the long term.

Based on the above analysis, we propose another hypothesis in this paper:

Hypothesis 2. The impact of price promotions on the purchasing behavior of consumers varies across different product categories. Products with lower price levels, higher sales levels, fewer products, and longer shelf lives exhibit better promotional performance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Econometric Method

This study built a reduced-form measurement model based on the literature review. Different regression analysis methods were used to empirically reveal the relationship between promotion characteristics and consumer behavior. The empirical regression model is shown as follows:

where

is the purchasing behavior of the consumers of store s in period

, which is measured by gross profit or turnover;

is a key variable matrix that includes the independent variables we are interested in, denoted as:

where cross-term mean the dummy variable of the holiday and promotion depth-holiday cross variables, respectively. Considering that supermarkets might attract more consumers by adjusting promotion depth on holidays, we paid particular attention to the cross-term of promotion depth and holiday.

represents the control variable matrix, including other major factors that affect supermarket performance and must be taken under control, including the seasonal dummy variable, per capita disposable income, and the population of the region where the store is located.

and

are the estimated regression coefficients of the key variable and control variable, respectively. Specifically, the estimated values of promotion duration, breadth, and depth can be used to verify if there is a positive correlation between supermarket performance and price promotion. Their ratios can be further used to analyze which means of price promotion was applied to improve supermarket performance. The error term is

.

Further, in order to examine the differences in the effect of supermarket promotions on consumer behavior across product categories, this study will use the cross-term coefficients between the category characteristics and the depth of promotions to estimate the heterogeneity of category characteristics. The main selected category characteristics are the average price, average sales volume, product quantity, and storage resistance of different categories. The estimated model is as follows:

where

represents the purchasing behavior of the consumers of store s in period

, which is measured by turnover or gross profit;

represents the control variable, including promotion duration, season, holidays, and population;

is the promotion depth of store s in period t;

shows the impact of the promotion depth of category i on the supermarket’s performance. The error term is

.

is a linear function that contains different features of category

i. It is defined as follows:

where

represents the characteristic

of category

, and

represents the effect of characteristic

on supermarket performance during the price promotion. Substituting (4) into (2), the following expression is obtained:

where

,

. The above model is taken logarithmically and expanded to obtain the following expression:

In Equation (7), is the sum of the category price level multiplied by the promotion depth; represents the sum of category sales multiplied by the promotion depth; represents the sum of the category sales level multiplied by the promotion depth; represents the sum of the category product quantity multiplied by the promotion depth; represents the sum of the promotion breadth multiplied by the promotion depth. The main role of the variable of promotion breadth in this chapter is as a control variable. The estimation of Equation (6) yields a series of estimates of , that is, the impact of each category characteristic variable on performance in the price promotion.

Bring the value of the category characteristics estimated in Equation (7) into (8) below:

is a linear function containing four category characteristics that affect supermarket performance. It is also the estimated value of the coefficient of the promotion depth variable of each category in Formula (3), which represents the impact of each category on performance during the price promotion.

The data structure used in this study is the panel data composed of 26 promotion seasons of 10 stores, so the empirical regression is mainly calculated by using the panel data model. Traditional panel data measurement models included fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models. The original hypothesis cannot be rejected by the Hausman test result in all cases after regression, which indicated that the RE model was superior to the FE model. To begin with, the regression analysis of the supermarket’s panel data was made using the RE model. Considering the possible store heteroscedasticity in panel data, a robust standard deviation was used in the RE model to correct the possible estimation deviation. Next, the endogeneity between key variables and supermarket performance was considered. Model regression was carried out using different traditional instrumental variables (IVs), with the most effective IV selected. Lastly, the generalized method of moments (GMM) was selected to measure model regression. The GMM estimation method is a statistical method used to estimate panel data models through the introduction of lagged variables by differencing panel data, so that the model includes dynamic characteristics and thus better reflects the relationship between variables. This method can be taken as a further robust result for the better use of different IVs to solve the endogenous problem in the model. Over-identification and autocorrelation tests were conducted after the regression of all IVs; therefore, the validity of the estimation result was ensured. In addition, a further robust analysis of the validity of the model structure was performed.

3.2. Micro-Level Supermarket Data

In this study, the one-year continuous scanner data from ten stores of a regional supermarket chain in eastern China in 2017 were used for the test. According to the information provided by the supermarket, there were 26 promotion seasons in the year and each promotion season lasted approximately 3–5 days. Over 23,000 items were involved, covering the vast majority of food and general commodities apart from fresh products. The data from affiliated items were excluded from the scanner data since these items are sold by independent merchants that rent the supermarket space and often launch promotion activities that differ from those of the supermarket. The stores were randomly selected by the administrative unit of the supermarket headquarters’ metropolitan area. In total, ten stores from seven municipal districts, each densely populated with a large number of supermarkets, were selected. All the stores were chain supermarkets following uniform requirements, standards, and scale, but the number of items on the supermarket shelves may have varied from store to store.

The scanner dataset primarily contained item category codes, item category names, item names, brand names, specifications, item purchase prices, retail prices, special offers (promotion activities), sales volume, turnover, gross profit, and gross profit margin. This dataset is one of the few microscopic scanner datasets from supermarkets that can be used for academic research in China. It is able to favorably reflect the pricing strategies supermarkets utilize for their consumers. Based on the above data, the following basic processing is required in this paper: (1) First, promotion data sheets and scanner data needed to be indexed by commodity code for lateral matching. Then, the data of 26 periods from 10 stores were integrated longitudinally to synthesize the overall data needed for the study, with information from a total of 619,1991 samples. (2) Since the profit of the affiliate merchandise is not internal to the supermarket and the supermarket only charges a certain amount of rent for the affiliate area, it is necessary to exclude the information related to the affiliate merchandise. (3) Since fresh foods are perishable, their loss rate is high, and their daily price fluctuations are large, supermarkets consider the sales data of fresh products separately. The data obtained in this study lack accuracy regarding fresh foods; therefore, it is necessary to exclude this information. (4) Abnormal values were excluded, including samples with sales below zero, samples with sales volumes below zero, and samples with zero commodity prices.

The data summarized at the store and product category levels were investigated according to this study’s research objectives. Specifically, the turnover and gross profit of each store during each promotion season—as well as the characteristic variable of price promotion—were calculated. Turnover and gross profit were taken as the explained variables measuring the effective purchasing behavior of consumers. Promotion breadth and depth at the store level appeared in percentage terms, which represented the proportion of promotional items in the total number of items and average discount rate, respectively. The depth of promotion at the product category level was expressed using the average depth of promotion for the different categories. Promotion duration refers to the period of a promotion from the beginning to the end. Product category was a classification based on the sales category of the store, and the products in the same category have certain complementarity and are able to be substituted for one another. Four variables were selected to characterize the category characteristics: average price of the product category, average sales volume, average number of products within the category, and storage resistance. Considering the holiday effect test, a dummy variable of the holiday was set based on important Chinese holidays during the period of analysis. The variables and their definitions are shown in

Table 1.

3.3. Data Description

According to the scanner data from the commodities, the results of the descriptive statistical analysis of each variable are presented in

Table 2. The table shows that the average promotion duration for the 10 stores was two weeks or less. At the store level, the average figure for promotion breadth was 3.70%, while the average figure at the category level reached 4.28%. The average value in terms of promotion depth was 30.10% at the store level, while at the category level, the average figure was 25.86%. From the perspective of performance, the average daily turnover and gross profit of the supermarket were approximately 1.30 million yuan and 139,000 yuan, respectively, and the average profit rate was 10.7%. In order to eliminate the influence of the economic and demographic environments of different regions on the operating performance of supermarkets, this study selected the population and per capita disposable income in the regions where the 10 stores were located as control variables. The population in the areas where the ten sample stores were located was approximately 300,000–1,000,000, and the annual disposable income was approximately 50,000 yuan. However, the population and disposable income data were not subject to the supermarket promotion periods, and thus represented only cross-sectional data.

Table 3 shows the four characteristic values for the 30 categories. In terms of the selling price, the last three, from lowest to highest, are daily bread, puffed food, and convenience food. The average price of the above three categories is below 10. The highest price levels, from highest to lowest, are small kitchen appliances, bed textiles, cookware, liquor, small office appliances, and baby diapers. The average price level of these six categories is above 100 yuan. Prices for the other 21 categories are between 10 and 100. Overall, the selling price between categories varies greatly.

From the category sales levels, the lowest sales, from lowest to highest, are small office appliances and swimwear. The sales of the above two categories are below 10 pieces. On the contrary, the highest sales, from highest to lowest, are condiments, refrigerated yogurt, puffed food, grain and oil, special paper, and daily paper. The sales of these six categories are above 1000 units. Sales in the other 22 categories ranged from 10 to 1000. In general, the categories with higher sales are those that consumers use more frequently or on a daily basis.

In terms of the quantity of products in the category, the category with the minimum number of products is small office appliances, with an average number of 10.75. The category with the maximum number of products is head care, with an average number of 780.8. Overall, the number of products varies greatly between categories.

4. Results

4.1. Empirical Analysis of Supermarket Promotions on Consumer Purchasing Behaviour

The Equations (1)–(5) in

Table 4 present the regression results of FE, IV, and GMM, respectively, and corrected the potential heteroscedasticity at the supermarket level. Meanwhile, the explained variables included supermarket turnover and gross profit, respectively.

Since the endogenous problem of promotion variables, promotion depth, promotion breadth, and cross-term cannot be solved by the fixed-effect regression (1), different instrumental variables were used to correct the endogenous bias in Equations (2)–(5). In this study, two main types of instrumental variables were applied: (i) the second and third lagged variables of the promotion depth and breadth; and (ii) the second and third lagged variables of the average values of promotion depth and breadth in other stores. In theory, the second kind of instrumental variable is more suitable for the traditional Longitudinal Panel with large N and small T. On the contrary, the first kind of instrumental variable can be applied to a Longitudinal Panel with large T and small N more aptly. The data, which were T = 26 and N = 10, can be seen as relative square (T ≈ N) panel data. Therefore, these two types of instrumental variables were applied at the same time to solve the endogenous problem, and the validity of instrumental variables was further verified by estimating outcomes. The lag time of the instrumental variables was tested. The researchers found that the first lag period of endogenous variables, as well as the current period and the first lag period of average sales of promotion depth and breadth in other stores, could not pass the validation test as instrumental variables. The finding revealed the relativity of these instrumental variables to random perturbation terms, explaining why they cannot be used as an effective instrumental variable. The main reason may be that the depth, breadth, and cross-term of the last period promotion of this store, or of the current promotion of other stores, were still strongly correlated with these three characteristics of this store in the current period. Meanwhile, the correlation of the characteristics of the season that exceeded a two-period span was relatively weak, which means not much impact was generated.

After the regression results were achieved via IV and GMM, over-identified and autocorrelation tests were carried out to verify the autocorrelation between the validity of instrumental variables and residuals. It should be noted that the autocorrelation test result of Arellano–Bond is not entirely reliable when T in panel data is relatively large. Although the panel data used were similar to the data of the square panel, T was still significantly larger than N. Caution is required when analyzing the results of autocorrelation tests, as is a detailed discussion of the results to verify the rationality of the main analysis outcomes.

4.1.1. Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Promotion Methods on Consumer Purchasing Behavior

The GMM results show that the depth, breadth, and duration of promotion in this study have remarkable positive effects on the purchasing behavior of consumers at the 1% level in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Specifically, the regression results measured by IV and the GMM show that for every 10% increase in promotion depth, the turnover will increase by approximately 0.1 million yuan, and for each one-day increase in promotion duration, the turnover will be increased by approximately 0.3 million yuan, indicating that a longer sales period will boost a larger trading volume. Moreover, the turnover will grow by approximately 1 million yuan as the promotion breadth is increased by 10%, which shows that the expansion of the promotion commodity scope will also increase the turnover. Furthermore, there will be a growth of 6000, 20,000, and 5000 yuan, respectively, in the gross profit with each 10% increase in the promotion depth and breadth, and with each additional day of the promotion duration.

Empirical results indicated that price promotion can significantly promote consumer purchasing behavior, which is reflected in the improvement of supermarket performance. This empirical result verifies Hypothesis 1, that is, supermarkets can improve consumers’ purchasing behavior by increasing the promotion depth and width. The research verified the rationality of Chinese supermarkets’ move to improve their business conditions and performance simultaneously. The regression results of turnover and gross profit were also a reflection of the fact that the impact of supermarket price promotion on gross profit was slightly greater than that on the turnover, further proving that price promotion can significantly improve supermarket performance.

Through further observation of the results in

Table 4 and

Table 5, the researchers found that the improvement in supermarket performance was mainly achieved by intertemporal price discrimination by prolonging the promotion period. In the Chinese retail market, consumers who are price-sensitive and time-insensitive account for a large part of the total, especially middle-aged and elderly consumers. The insensitivity of middle-aged and elderly consumers to time in the retail markets indicates that they are willing to wait for the promotion of specific commodities. This confirms, to a certain extent, the effectiveness of the theory of intertemporal price discrimination. At the same time, supermarket performance can be enhanced by broadening the scope of promotional goods and enhancing the multiproduct pricing effect. In real life, this mainly appears as the loss leader pricing that is often seen in large-scale supermarkets, such as the frequent price promotion of eggs in major community supermarkets. The effect of promotion depth on supermarket performance was relatively small, indicating that supermarkets were not constrained by the strategy of price reduction for profit increase by attracting more price-sensitive consumers. However, the literature has not explained price promotion strategies in a comprehensive way.

Estimates of the cross variables between promotion depth and holiday dummy variables show that increased price promotion during holidays will remarkably increase the supermarket’s turnover, although its elasticity coefficient is too small to significantly impact supermarket profits. The underlying reason may be that the holiday period is the peak period for consumption in supermarkets, and the profit from the large-scale sales of promotional commodities will not be sufficient to compensate for the loss caused by the promotion. This further demonstrates the limitation of price promotion competition theory for practically improving supermarket performance. Empirical results further show that the holiday dummy variables themselves at the level of 1% have a negative impact on trading volume, but the impact on gross profit is not obvious.

4.1.2. Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Promotion Methods on the Performance of Promotional and Non-Promotional Products

Table 6 and

Table 7 show the empirical results of the effects of different promotion methods on the performance of promotional and non-promotional goods. Models (1) and (2), respectively, show the regression results of promotion methods on the turnover of promotional goods and non-promotional goods by using the random effects method. Model (3) estimates the regression results of promotion methods on the turnover of promotional and non-promotional goods after correcting for endogeneity in the model by using the GMM approach. Models (4) and (5), respectively, show the regression results of promotion methods on the gross profit of promotional goods and non-promotional goods by using the random effects method. Model (6) also shows the regression results of promotion methods on the gross profit of promotional and non-promotional goods after correcting for endogeneity using the GMM approach.

The results of

Table 6 and

Table 7 show that the impact of different promotion methods on the overall performance of supermarkets comes from two aspects. First, the price reduction of some goods attracts price-sensitive consumers, causing them to increase the number of purchases of promotional goods. Supermarkets increase their turnover and gross profit through small profits but quick turnover. Second, due to the high switching costs, consumers are locked in the supermarkets and will buy some planned but not promoted goods or increase their purchases of non-promotional goods in the process of loitering. These behaviors in turn lead to the sales of non-promotional goods, thus increasing the turnover and gross profit of the supermarkets. This empirical result further verifies Hypothesis 1, that is, supermarkets not only promote consumers to purchase promotional products but also increase consumers’ purchase of non-promotional products through the increase of promotion depth and breadth. In general, with the increase of promotion depth and promotion breadth in supermarkets, consumers increase their purchase behavior.

4.2. Category Heterogeneity Analysis of the Effect of Supermarket Promotions on Consumer Purchasing Behaviour

Table 8 shows the impact on the performance of supermarkets when price promotions for different category characteristics are applied. Since the first four variables in

Table 8 are cross-terms of the price level, sales quantity, products quantity, storage resistance, and promotion depth, promotion depth is an endogenous variable. Therefore, the dynamic GMM method is directly used to estimate the coefficients in this section to correct the endogeneity problem in the model. Model (1) shows the impact of different category characteristics on the turnover of large comprehensive supermarkets during the promotion. Model (2) shows the impact of different category characteristics on the gross profit of large comprehensive supermarkets during the promotion. The results show that the cross-terms of the four characteristic variables and promotion depth are significant at the 1% level.

According to the regression results, the cross-term price characteristics of product categories and promotion depth have a significantly negative impact at the 1% level on supermarket performance. This indicates that although the discount on higher-priced categories results in more savings perceived by consumers than lower-priced categories, the higher-priced categories also lose more profit relative to the original high price. The increase in profits from increased sales is not enough to compensate for the decrease in profits from lower prices, which ultimately leads to a decrease in gross profits. In addition, goods with high price levels require consumers to pay more in transaction costs when they are on sale, and if the goods are not part of the purchase plan, this extra expense has a greater impact on the budget and makes impulse purchases less likely. Second, the cross-term of category sales volume and promotion depth has a significant positive impact on performance. Because the category with high sales volume is the category that consumers often buy, and when its price is reduced, consumers who had planned to buy products within the category buy the same number of products as planned or buy even more because of a lower price than psychologically expected. In addition, consumers who did not plan to buy such products are attracted by the promotional information and perceive the increased value of buying the product, leading to purchase behavior. The combined result of these two consumer behaviors is that although the price promotion leads to a decrease in the transaction value and gross profit per unit of the good, the turnover and gross profit eventually increase due to increased purchases of the good by consumers. Third, the cross-term of the number of products in the category and promotion depth has a significantly negative effect on performance. This is because of the large number of products in the category and the fierce competition, leading to an increase in consumer search costs which then affects the promotion effect. Fourth, the impact of the cross-term of storage resistance and promotion depth on performance is significantly positive. The main reason is that price promotions for storage-resistant products can encourage consumers to buy and stock up, which in turn increases performance as the significant increase in sales volume offsets the loss from product price reductions. These regression results verify Hypothesis 2 proposed above. That is, the promotion of different product categories has different effects on consumers’ purchasing behaviors. Promotions for categories with lower prices, higher sales, fewer product categories, and better storage endurance can better promote consumer purchase behavior.

In terms of control variables, promotional breadth remains significantly positive in this model. It illustrates that multi-product collaborative promotion can drive an increase in consumer consumption. Due to the increase in the number of promotional products, consumers increase their purchases and promote the increase in supermarket performance. In the dynamic GMM model, the one-period lags of turnover and gross profit have a significantly positive effect on current period turnover and gross profit, respectively. The possible reason is that supermarkets attract a large number of consumers to engage in store-switching behavior through price promotions, and these consumers will continue to make purchases at the supermarket in the next period after enjoying the benefits brought by the price promotions, thus contributing to the increase in supermarkets’ performance in the current period.

After estimating the coefficients of the four category characteristics, the coefficients are substituted into Equation (8). Since each category has four values corresponding to its characteristics, the estimates in Equation (3) can be obtained by Equation (8), i.e., to obtain the degree of impact on supermarket performance when each category is price-promoted. The estimated results are shown in

Table 9 below. The first column shows the impact of each category on the logarithm of the turnover during price promotion. A total of 16 out of the 30 categories examined have a negative impact on turnover during price promotion. The biggest negative impact of price promotion on the turnover is from small kitchen appliances, when the depth of promotion of this category increases by 10%, the transaction value will fall by 10.22%. On the contrary, the biggest positive impact of price promotion on the turnover is from special paper, when the depth of promotion of this category increases by 10%, the transaction value will increase by 6.08%. The second column in

Table 9 shows the impact of each category on the logarithm of gross profit during price promotion. A total of 14 categories have a negative impact on gross profit, among which the category with the largest negative impact on gross profit is also small kitchen appliances. When the promotion depth of this category increases by 10%, the gross profit will decrease by 9.77%. The category with the greatest positive impact on gross profit is still special paper. When the depth of promotion increases by 10%, gross profit will increase by 5.99%. A comparison of the estimates in the turnover and gross profit models reveals a high degree of consistency between the positive and negative estimates in the first and second columns. Among them, oral care and condiments have a negative impact on turnover and a positive impact on gross profit when price promotions are conducted. In addition, the 30 categories differed in the degree of impact on the turnover and gross profit.

5. Discussion

The effect of price promotions on the performance of supermarkets is complicated. Because of the uncertainty of consumers’ behavior, such as whether consumers enter the supermarket, which products they choose to buy, and how much they spend, the returns from price promotions are unpredictable. Earlier researchers proved that consumer traffic, sales, and profits are indicators of supermarkets’ performance resulting from price promotions. As a result of low-price promotions for specific products, supermarkets get a rapid increase in customer traffic, and consumers boost supermarket business performance by increasing their purchases of discounted products [

38]. Moreover, the increase in customer traffic promotes the purchase of non-discounted items, hence improving supermarkets’ overall performance [

39]. These research conclusions are also confirmed in this study. Consumers not only increase the purchase of promotional products but also purchase non-promotional products. Kamins et al. (2004) further revealed that 60% of the items in consumers’ shopping baskets at supermarkets are unplanned, and the purchase of unplanned products unquestionably increases each customer’s transaction amount [

40]. Therefore, when making promotional decisions, supermarket managers attempt to boost at least one of consumer traffic, conversion rate, or sales [

41].

Studies have also shown that, depending on how supermarket performance is portrayed, promotions do not always have favorable benefits on supermarket performance. Walters et al. (1988) found that the majority of advocate loss price promotions have no substantial impact on gross profit [

42]. The impact on profits was primarily caused by changes in consumer traffic, rather than product sales. Ailawadi et al. (2006) found that promotions had a positive impact on retail sales with a significant positive “halo effect”, meaning that for every unit reduction in product price, 0.16 units of other products were purchased simultaneously [

43]. However, the study did not find a significant effect of price promotion behavior on gross profit. Li et al. (2021) revealed that the influence of promotions on supermarket performance would diminish as the duration of promotions progressed, hence continuous promotions could not always produce an increase in supermarket profits [

44]. This study also found that there are 16 categories of commodities with promotions that have a negative impact on supermarket turnover, and there are 14 categories of commodities with promotions that have a negative impact on supermarket gross profit.

Several other researchers have examined the mechanism underlying the influence of promotional strategies on the purchasing behavior of consumers. From the consumer’s point of view, deep discounts appeal to customers by encouraging them to enter the store and purchase more items that will enable the supermarket to be profitable [

45]. The degree of the discount influences consumer perceptions, and there exists a discount threshold. Consumers do not notice a price change when the discount is less than 15%, and there is little variation in how consumers perceive their savings when the discount is between 30% and 50% [

46]. Deep price reductions provide consumers with a perk that will make them more interested in the promoted item [

47]. Discounts vary in their appeal to consumers because the amount of the discount differs from what people expect. Consumers’ attention will be drawn to discounts that exceed the minimum threshold [

48]. The results of this study also reveal that supermarkets can attract consumers to purchase commodities by increasing the promotion depth and width and increasing the promotion duration can also promote consumers’ purchasing behavior, thus improving supermarket performance.

From a product viewpoint, different product categories have distinct effects when promoted. There are cross-category variances in the promotional effects of the relationship between category variables, including average purchase period, household penetration, private label proportion, and price promotion performance [

31]. Interactions exist between the impacts of distinct categories. Using supermarket scanner data, Leeflang et al. (2008) decomposed the price promotion effect of a category and found that the complementary effect across categories accounted for 20%, which was higher than the replacement effect (11%) [

49]. Similarly, product differences might affect sales during the promotion. In contrast to items with lower average costs and greater storage resistance, heavier products and more competitive products exhibit less volatility in sales during price promotions [

21]. Promotions are more successful when frequently bought items or those with more brand recognition are selected [

46]. This is also verified in this study. For the categories with a higher sales quantity, the deeper the discount is, the higher the promotion degree of consumers’ purchase behavior is. During price promotions, perishable goods are more likely to be discounted so that customers will eat more of them [

43]. However, there is more producer value added for perishable items than for those that can be stored. Typically, supermarkets pick one item for promotion in several perishable categories (e.g., liquid milk, ground beef, etc.) and multiple items for promotion in non-perishable categories, indicating that customers value non-perishable goods more than perishable ones [

50]. The results of this study confirm that discounting storable goods promotes consumer purchase behavior more than discounting perishable goods.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

6.1. Conclusions

In this research, the relationship between three characteristics of price promotion and consumers’ purchasing behavior was studied based on commodity scanner data from a Chinese supermarket. The researchers analyzed whether promotional pricing could promote consumer purchase behavior by examining the causal relationship between the three major characteristics of price promotion (promotion depth, breadth, and duration), supermarket sales, and gross profit. The results show that promotions can contribute to the overall performance of supermarkets and drive the sales of non-promotional items. The significant positive effects of promotion depth, promotion breadth, and promotion duration on supermarket performance also indicate that price competition strategy and multi-product pricing strategy play an important role in the market competition of large integrated supermarkets. Large integrated supermarkets not only attract price-sensitive consumers to buy products by lowering prices to improve performance but also broaden the scope of merchandising and enhance the realization of multi-product pricing effects.

Heterogeneity studies based on category characteristics have shown that the impact of different categories of products on consumers’ purchasing behavior in promotional activities varies significantly. A total of 14 of the 30 categories have a positive impact on transaction value during price promotions, and 16 categories have a positive impact on gross profit during price promotions. In price promotion activities, the category with the largest negative impact on turnover and gross profit is small kitchen appliances, and the category with the largest positive impact is special paper.

The impact of different category characteristics on consumers’ purchasing behavior in promotional activities also varies significantly. The sales volume and storage resistance of the category have significant positive effects on supermarket turnover and gross profit. The price level and the number of products included in the category have significant negative effects on supermarket turnover and gross profit. This finding illustrates that when price promotions are conducted, since categories with high average sales volume are those with high purchase frequency, compared with the categories with low purchase frequency, they are more likely to attract consumers’ attention and promote purchase behavior, improving performance. When storage-resistant categories undergo price promotions, consumers can stock up for future use. Therefore, stocking behavior promotes performance. The increase in consumption due to higher-priced categories cannot compensate for the decrease in transaction value and profits. A large number of products in the category increases the search cost for consumers, so consumers with high time costs are not willing to spend time searching for such promotional items.

6.2. Enlightenment

Studying the effect of supermarket promotions on consumers’ purchasing behavior is of great practical significance for supermarket managers to formulate price strategies as well as for the sustainable development of the retail industry. This research suggests the following two policy implications. First, the improvement of price promotion depth for Chinese supermarket performance is limited. Deep discounts on a limited number of products cannot attract enough consumers—and may primarily appeal to a large number of consumers who only buy products at the lowest price—resulting in limited improvements in supermarket performance. Thus, decision-makers should balance the depth and breadth of promotions by increasing consumer search costs through multi-product pricing to further increase sales of non-promotional products and ensure performance growth. Decision-makers should take advantage of Chinese holidays, the peak demand period for goods by consumers as they enjoy leisure activities, to enhance supermarket performance. Empirical results also confirm this viewpoint, with the cross-term of holiday and promotion depth having a significant positive impact on transaction volume. As a signal of price promotions, holidays provide additional opportunities to increase Chinese supermarket sales.

Second, supermarket decision-makers need to choose promotional items reasonably and carefully when formulating promotion strategies to improve performance through multi-category synergy promotion strategies. The effectiveness of different categories in conducting price promotions varies greatly, and a wrong choice can, on the contrary, lead to a decline in performance. According to the conclusion of this paper, the categories with low average price, storage resistance, a small number of products, and high purchase frequency of consumers should be selected for price promotion, which will be more helpful for performance improvement.

6.3. Limitations and Prospects

In this study, we have two main limitations. The first aspect mainly lies in the lack of information from supermarkets. Due to the privacy inherent in supermarket operations, we cannot obtain more specific operational characteristic data related to each supermarket store. Therefore, we cannot control some operation index variables in the analysis, which may lead to some errors in our results. Another shortcoming is the lack of information relevant to consumers. We cannot obtain consumer characteristics corresponding to sales records, so the analysis of different consumer purchasing behaviors is not specific enough. In this study, it can only be inferred theoretically that price promotion promotes the purchase behavior of time-sensitive and price-sensitive consumers, but it cannot be tested through empirical analysis. Future research can be extended and expanded in these two aspects. The problem of insufficient information from enterprises can be solved by the research method of case analysis, and consumer research can be carried out for the study of consumer characteristics.