Sustainable Labels in Tourism Practice: The Effects of Sustainable Hotel Badges on Guests’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Signs

2.2. Sustainable Hotel Badges

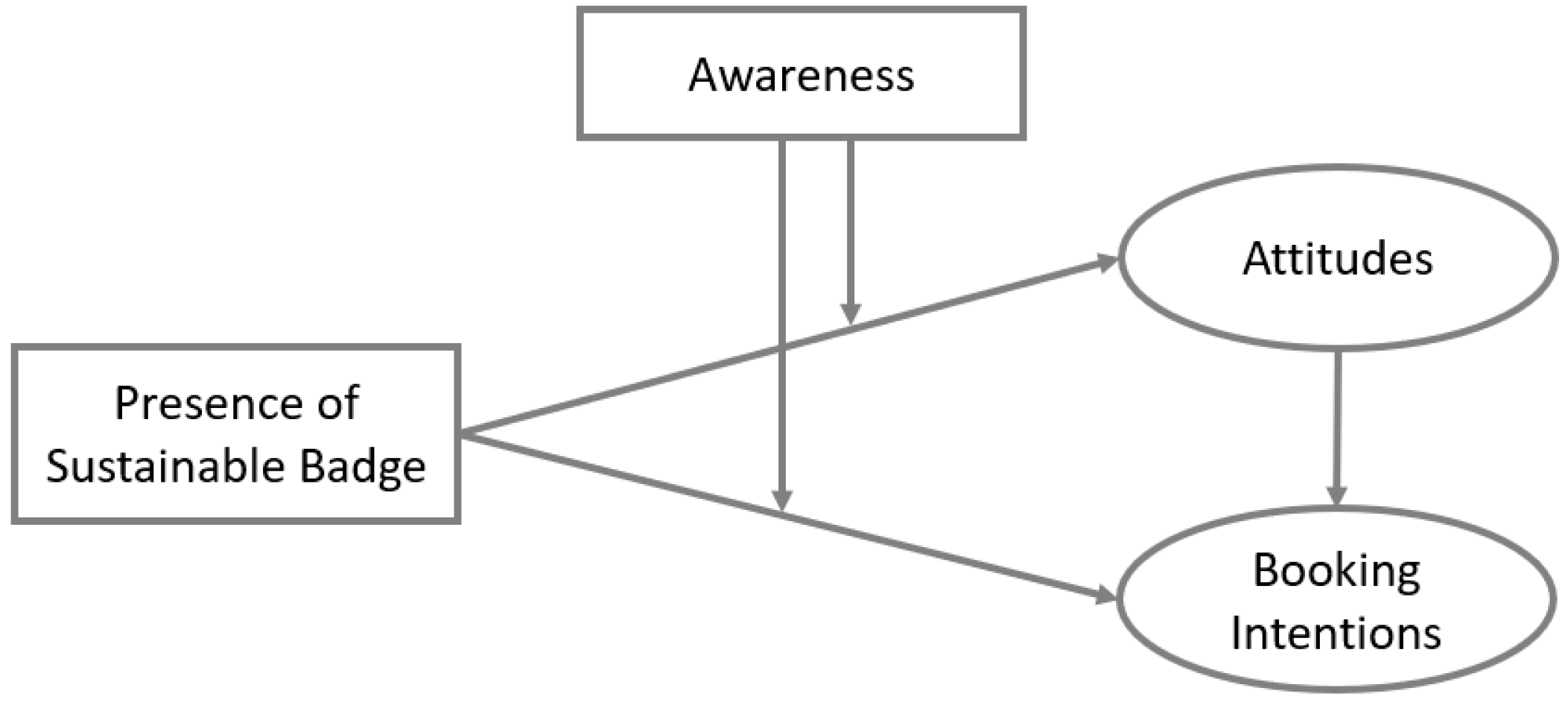

2.3. The Effects of the Presence of Sustainable Hotel Badges on Guests’ Attitudes and Booking Intentions

2.4. The Effects of Awareness of Sustainable Practices

2.5. Mediation Effects of Attitudes in the Relationships between the Presence of a Sustainable Badge and Booking Intentions

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Research Instruments

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The Effects of the Presence of a Sustainable Badge

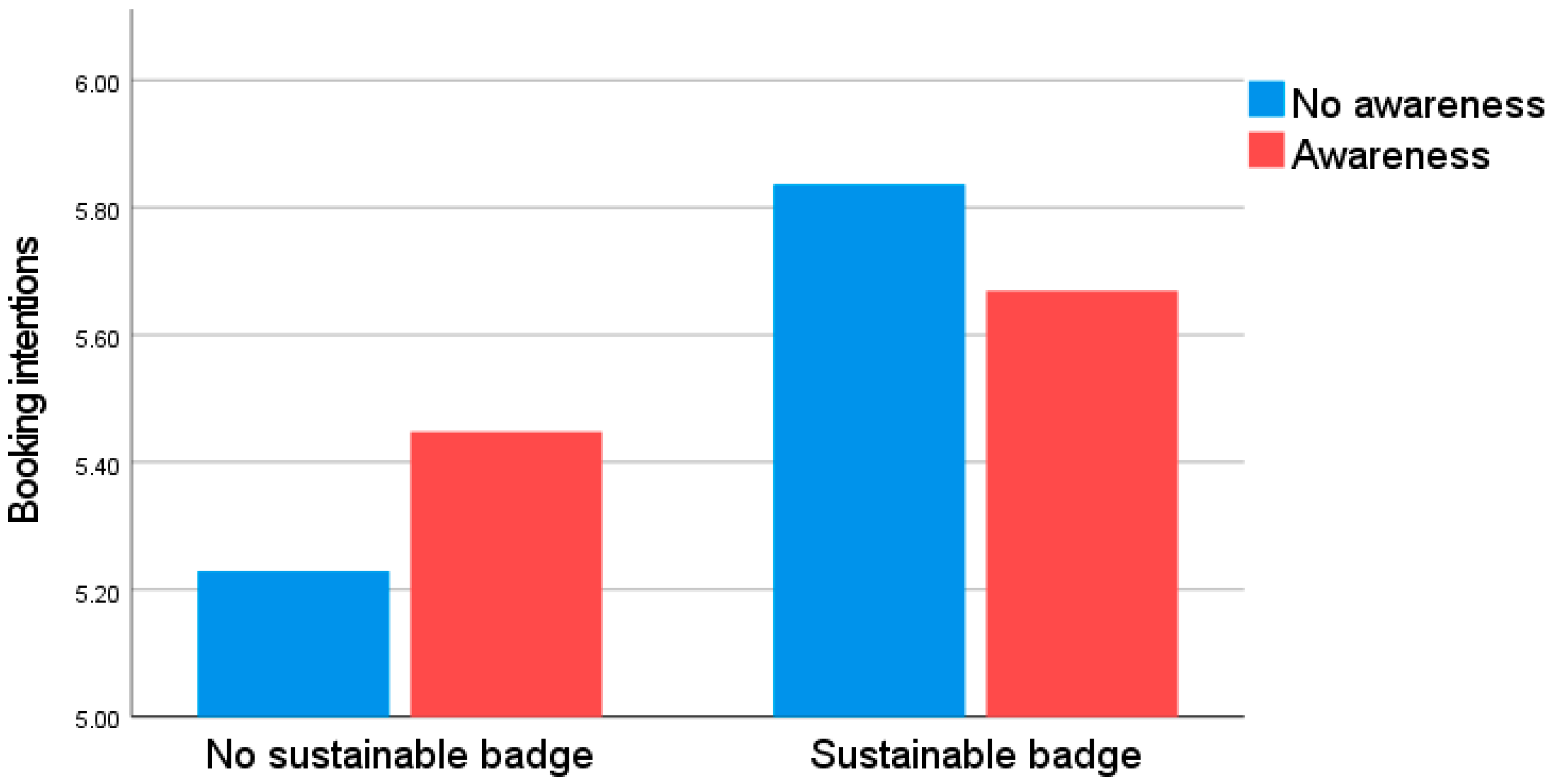

4.3. Moderating Effects of the Awareness of the Sustainable Practices

4.4. Mediating Effects of Attitudes

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borges-Tiago, M.T.; Arruda, C.; Tiago, F.; Rita, P. Differences between TripAdvisor and Booking. com in branding co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Mellinas, J.P. Hotels that most rely on Booking. com–online travel agencies (OTAs) and hotel distribution channels. Tour. Rev. 2018, 74, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booking.com. Travel Sustainable. 2023. Available online: https://www.sustainability.booking.com/booking-travel-sustainable (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Green hotel knowledge and tourists’ staying behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2211–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majer, J.M.; Henscher, H.A.; Reuber, P.; Fischer-Kreer, D.; Fischer, D. The effects of visual sustainability labels on consumer perception and behavior: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, S.E.; Sexton, A.L. Conspicuous conservation: The Prius halo and willingness to pay for environmental bona fides. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 67, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. It’s not easy being green: The effects of attribute tradeoffs on green product preference and choice. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, F.; Kurz, V.; Bryngelsson, D.; Hedenus, F. Carbon label at a university restaurant–label implementation and evaluation. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elofsson, K.; Bengtsson, N.; Matsdotter, E.; Arntyr, J. The impact of climate information on milk demand: Evidence from a field experiment. Food Policy 2016, 58, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Van Koppen, C.S.A.; Janssen, A.M.; Hendriksen, A.; Kolfschoten, C.J. Consumer responses to the carbon labelling of food: A real life experiment in a canteen practice. Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Y.; Lewis, A.N.; Dawkins, E.; Grah, R.; Vanhuyse, F.; Engström, E.; Lambe, F. Information as an enabler of sustainable food choices: A behavioural approach to understanding consumer decision-making. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Merli, R.; Lucchetti, M.C. Ecolabel certification, hotel performance, and customer satisfaction: Analysis of a case study and Future Developments. In Advances in Global Services and Retail Management; Cobanoglu, C., Della Corte, V., Eds.; USF M3 Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Hay, J.E. Tourism and Climate Change: Risks and Opportunities; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, J.; Font, X.; Wu, J. Code red for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, E.; Hofmann, E.; Hartl, B. Fostering sustainable travel behavior: Role of sustainability labels and goal-directed behavior regarding touristic services. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. BESR in the hotel sector: A look at tourists’ propensity towards environmentally and socially friendly hotel attributes in Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2004, 5, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Pizam, A.; Bahja, F. Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S.; Lee, S. A meta-analysis of behavior intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; Colmekcioglu, N. Understanding guests’ behavior to visit green hotels: The role of ethical ideology and religiosity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Ali, F. Why should hotels go green? Insights from guests experience in green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, M.; He, Y.; Lin, I.; Mattila, A.S. Understanding guests’ evaluation of green hotels: The interplay between willingness to sacrifice for the environment and intent vs. quality-based market signals. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.; Man, H.W. The influence of store image on store loyalty in Hong Kong’s quick service restaurant industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2002, 5, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Wong, S.C. Motivations for ISO 14001 in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Roseman, M.G. The effect of non-optional green practices in hotels on guests’ behavioral intentions. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sáinz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.; Bagheri, P.; Tümer, M. Decoding behavioural responses of green hotel guests: A deeper insight into the application of the theory of planned behaviour. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2509–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, X.; Jai, T.M. Hotel guests’ perception of best green practices: A content analysis of online reviews. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Xuhui, W.; Nasiri, A.; Ayyub, S. Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Quality and preference 2018, 63, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skallerud, K.; Armbrecht, J.; Tuu, H.H. Intentions to consume sustainably produced fish: The moderator effects of involvement and environmental awareness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y. The Relationship Between Students’ Awareness of Environmental Issues and Attitudes Toward Science and Epistemological Beliefs—Moderating Effect of Informal Science Activities. Res. Sci. Educ. 2023, 53, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P.; Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O. The measurement of green workplace behaviors: A systematic review. Organ. Environ. 2021, 34, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. Environmental behavior in a private-sphere context: Integrating theories of planned behavior and value belief norm, self-identity and habit. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 148, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araújo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- leedo-Díaz, A.B.; Andreu, L.; Beckmann, S.C.; Miller, C. Negative online reviews and webcare strategies in social media: Effects on hotel attitude and booking intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Michaud, M. eWOM effects on hotel booking intentions, attitudes, trust, and website perceptions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Moscardo, G. Understanding the impact of ecotourism resort experiences on tourists’ environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.J.; Zhang, L. The impact of hotel room colors on affective responses, attitude, and booking intention. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2023, 24, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; MacInnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.F.; Jang, S.S. The effects of perceived price and brand image on value and purchase intention: Leisure travelers’ attitudes toward online hotel booking. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2007, 15, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Mattila, A.S. Airbnb: Online targeted advertising, sense of power, and consumer decisions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 60, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Lee, J.-S.; Kim, W. Impact of hotels’ sustainability practices on guest attitudinal loyalty: Application of loyalty chain stages theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 905–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. “Green” practices as antecedents of functional value, guest satisfaction and loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 722–738. [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, S.; Bernard, S.; Singal, M. The impact of sustainability certifications on performance and competitive action in hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequencies | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 364 | 67.8 |

| Female | 172 | 32.0 |

| Other | ||

| Age | ||

| 18–29 years old | 102 | 19.0 |

| 30–44 years old | 385 | 51.6 |

| 45–59 years old | 40 | 16.0 |

| 60 or older | 10 | 4.7 |

| Education | ||

| High School | 83 | 10.5 |

| Vocational School | 28 | 10.5 |

| College/University | 285 | 55.9 |

| Master’s or PhD | 140 | 22.9 |

| Other | 1 | 0.2 |

| Income | ||

| Under 30,000 | 37 | 21.2 |

| 30,000–49,999 | 173 | 28.7 |

| 50,000–79,999 | 229 | 30.9 |

| More than 80,000 | 98 | 19.2 |

| No Badge | Badge | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | 5.343 | 5.612 | 8.183 | 0.004 * |

| Booking intentions | 5.336 | 5.581 | 6.275 | 0.013 * |

| No Information | Information | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | 5.500 | 5.485 | 0.017 | 0.896 |

| Booking intentions | 5.470 | 5.472 | 0.000 | 0.991 |

| Hypotheses | Testing Result |

|---|---|

| H1 Sustainable badge → Attitudes | Supported |

| H2 Sustainable badge → Booking intentions | Supported |

| H3 Awareness → Attitudes | Rejected |

| H4 Awareness → Booking intentions | Rejected |

| H5 Sustainable badge × Awareness → Attitudes | Rejected |

| H6 Sustainable badge × Awareness → Booking intentions | Supported |

| H7 Sustainable badge → Awareness → Booking intentions | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godovykh, M.; Fyall, A.; Baker, C. Sustainable Labels in Tourism Practice: The Effects of Sustainable Hotel Badges on Guests’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062484

Godovykh M, Fyall A, Baker C. Sustainable Labels in Tourism Practice: The Effects of Sustainable Hotel Badges on Guests’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062484

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodovykh, Maksim, Alan Fyall, and Carissa Baker. 2024. "Sustainable Labels in Tourism Practice: The Effects of Sustainable Hotel Badges on Guests’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062484

APA StyleGodovykh, M., Fyall, A., & Baker, C. (2024). Sustainable Labels in Tourism Practice: The Effects of Sustainable Hotel Badges on Guests’ Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. Sustainability, 16(6), 2484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062484