The Implementation of Integrated Coastal Management in the Development of Sustainability-Based Geotourism: A Case Study of Olele, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Geotourism

2.2. Integrated Coastal Management (ICM) and Indicators of Sustainable Development in Coastal Areas

3. Methods

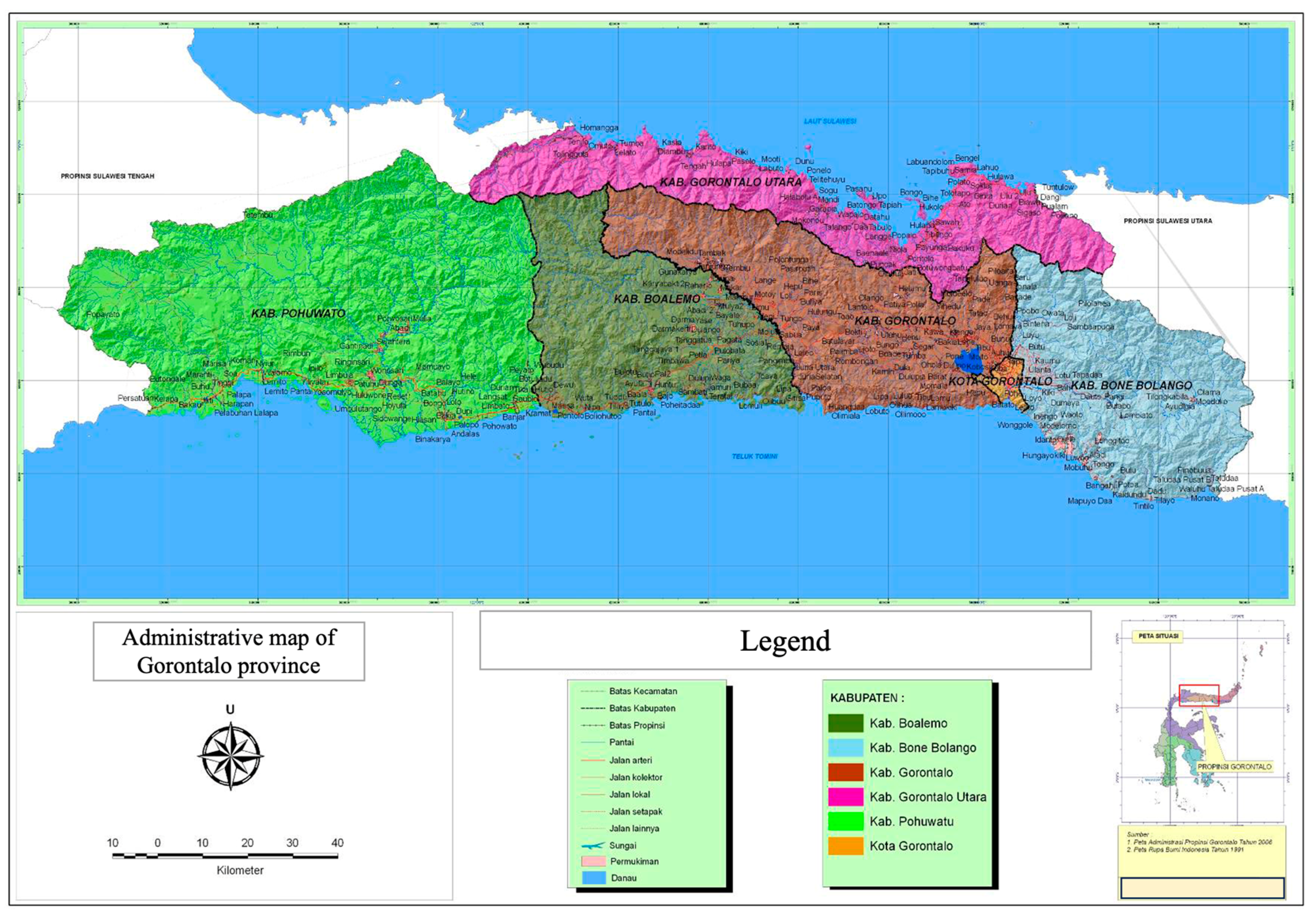

3.1. Research Location

3.2. Research Participants and Data Collection Techniques

- Individuals possessing expertise, discernment, practical know-how, specialized methodologies, and problem-solving capabilities, such as an academic instructor, a consultant, a corporate executive, a government representative, a tourism sector participant, or a local administrative officer.

- In order to become an expert and effectively complete the questionnaire, it is essential to possess relevant experience and an appropriate educational background and to engage in volunteer activities.

- Elucidate the process of program planning.

- Decompose the software into multiple sub-elements.

- Establish contextual linkages among the sub-elements within each element.

- In order to examine the contextual links between sub-elements, experts are required to develop a structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) for each element. This matrix is filled in by the experts using the symbols V, A, X, and O.

- V: The sub-element i has an impact on the sub-element j.

- A: The sub-element i is impacted by the sub-element j.

- X: There exists a reciprocal relationship between the sub-elements i and j.

- O: There is no discernible relationship between the sub-elements.

- Construct a reachability matrix (RM) for each individual element.

- Once the structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) has been generated, a reachability matrix table is constructed by assigning the values of 0 or 1 to the letters V, A, X, and O.

- V: Eij = 1 and Eji = 0.

- A: Eij = 0 and Eji = 1.

- X: Eij = 1 and Eji = 1.

- O: Eij = 0 and Eji = 0.

- The subsequent analysis of the RM involves identifying level-division choices in accordance with transitivity principles. The process of tabulation involves completing a predetermined format, and it can be facilitated through software.

- Transform the RM into a cone matrix, undertaking a conversion process.

- The task at hand involves creating a digraph that reflects the relationship established in the RM and subsequently adjusting the transitive link inside this digraph.

- Transform the resulting digraph into an ISM model; the element codes should be substituted with corresponding statements.

- The affected sectors of society.

- Program needs.

- The main obstacle.

- Program objectives.

- The institutions involved in implementing the program.

4. Results and Data Analysis

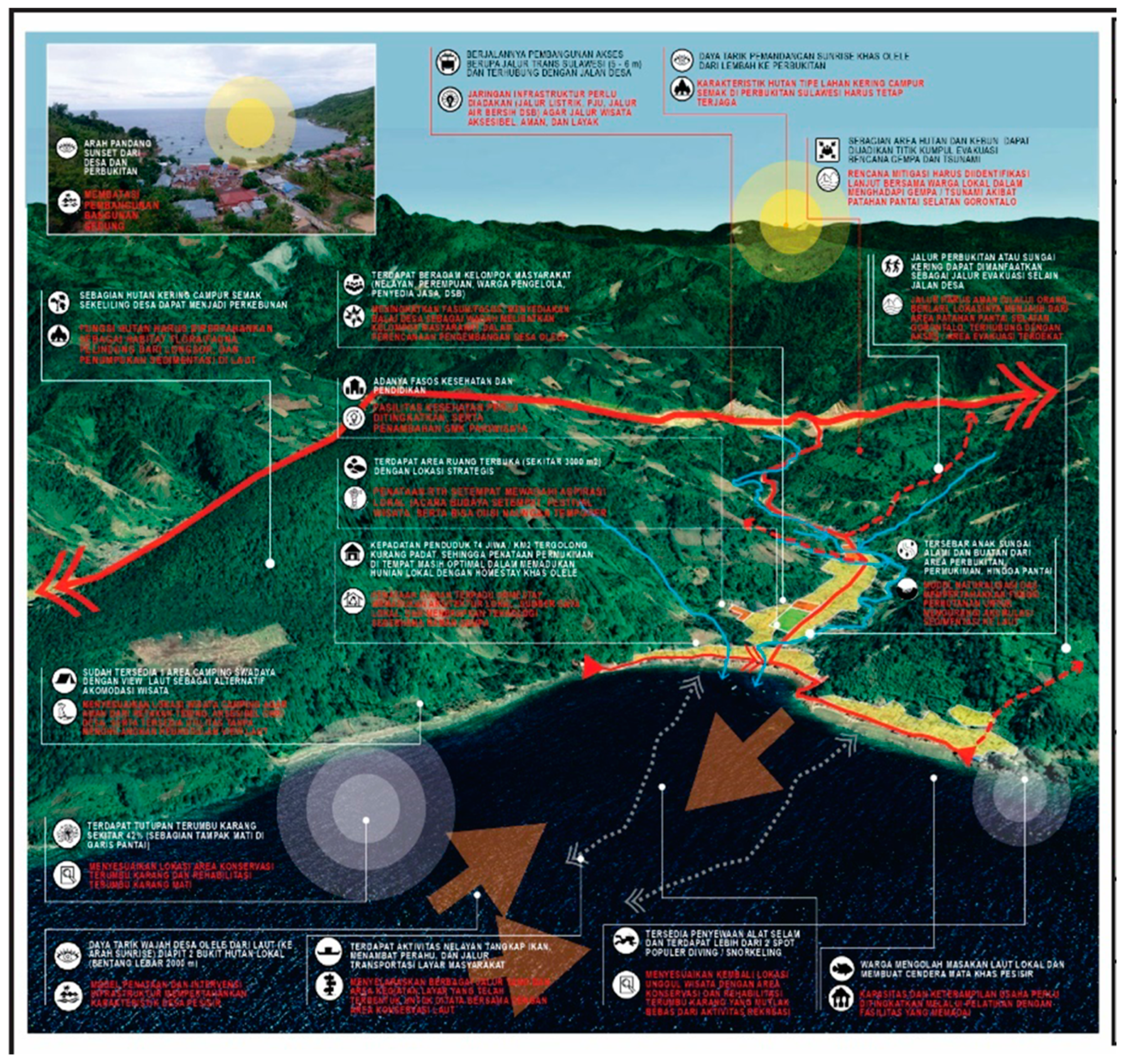

4.1. The Prospective Cartography and Zoning of the Olele Marine Park Area as a Geotourism Destination Applying Integrated Coastal Management (ICM)

4.2. Sustainable Marine Tourism Development Model Based on an Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) Approach in Olele Geotourism

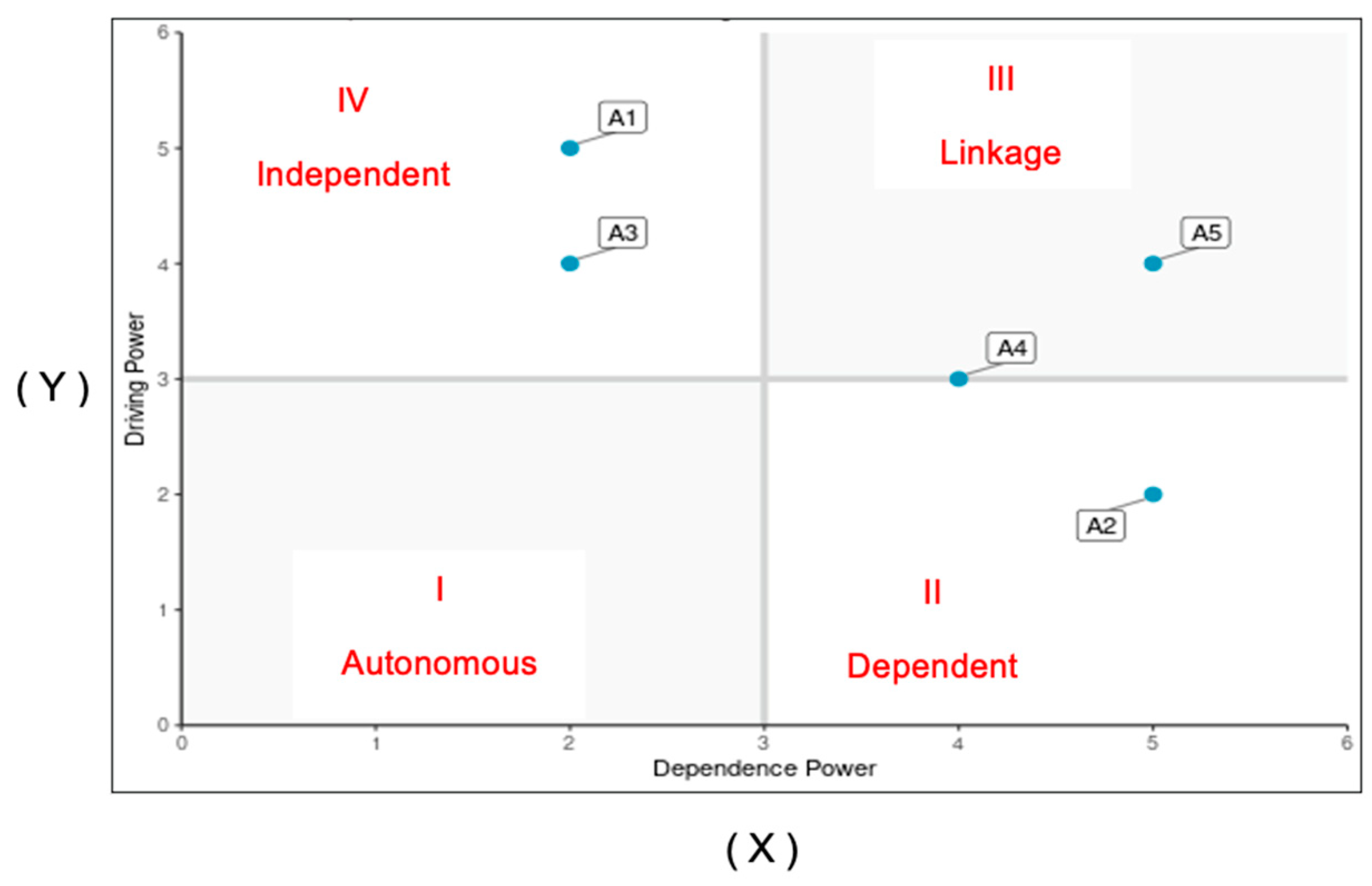

4.2.1. Affected Sectors of Society

- A1: Village community livelihoods.

- A2: Fishing activities (fishermen).

- A3: Marine tourism activities (diving, snorkeling, and other water sports).

- A4: Village facilities and infrastructure and the surrounding environment.

- A5: Business actors (MSMEs) or tourism services.

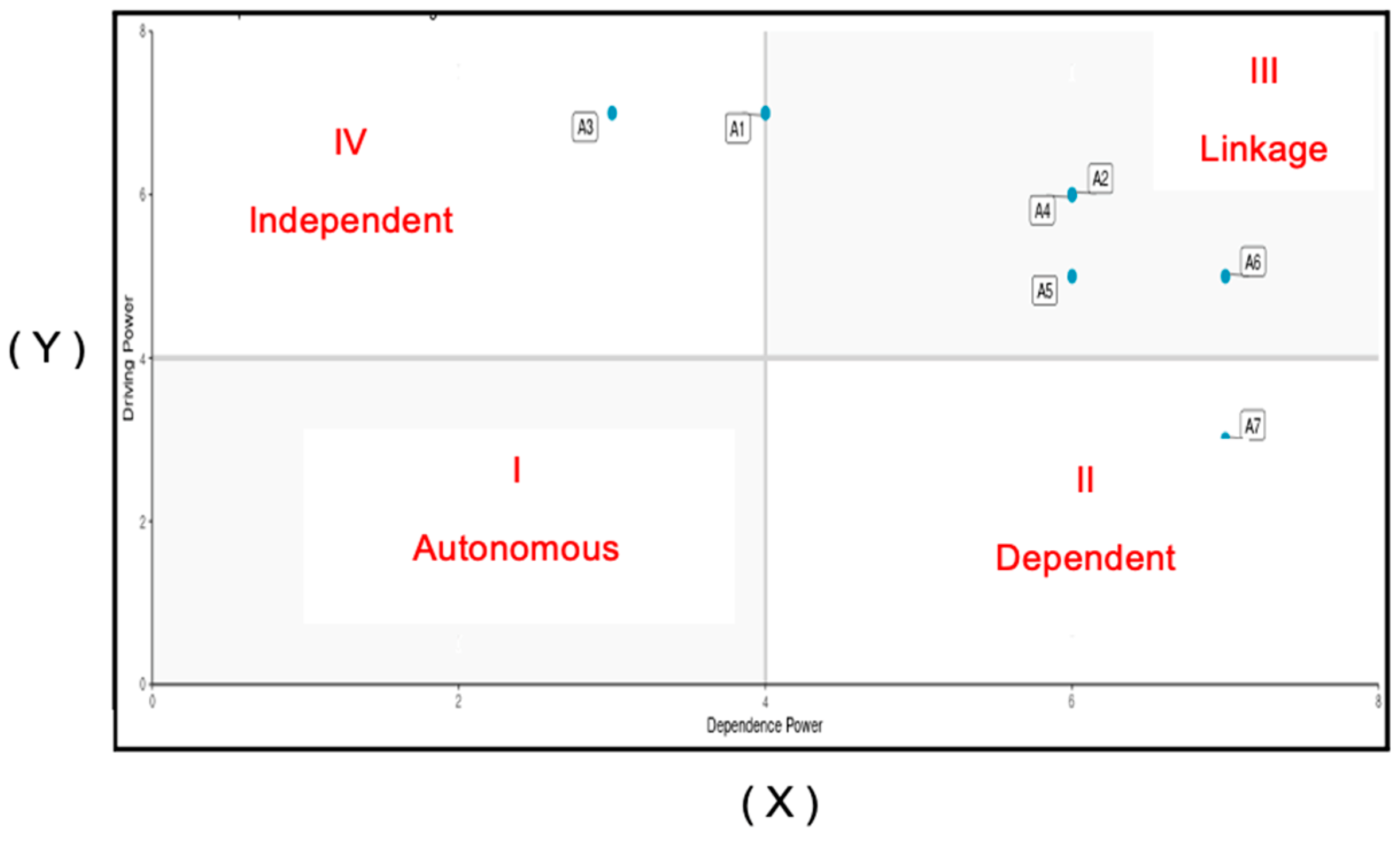

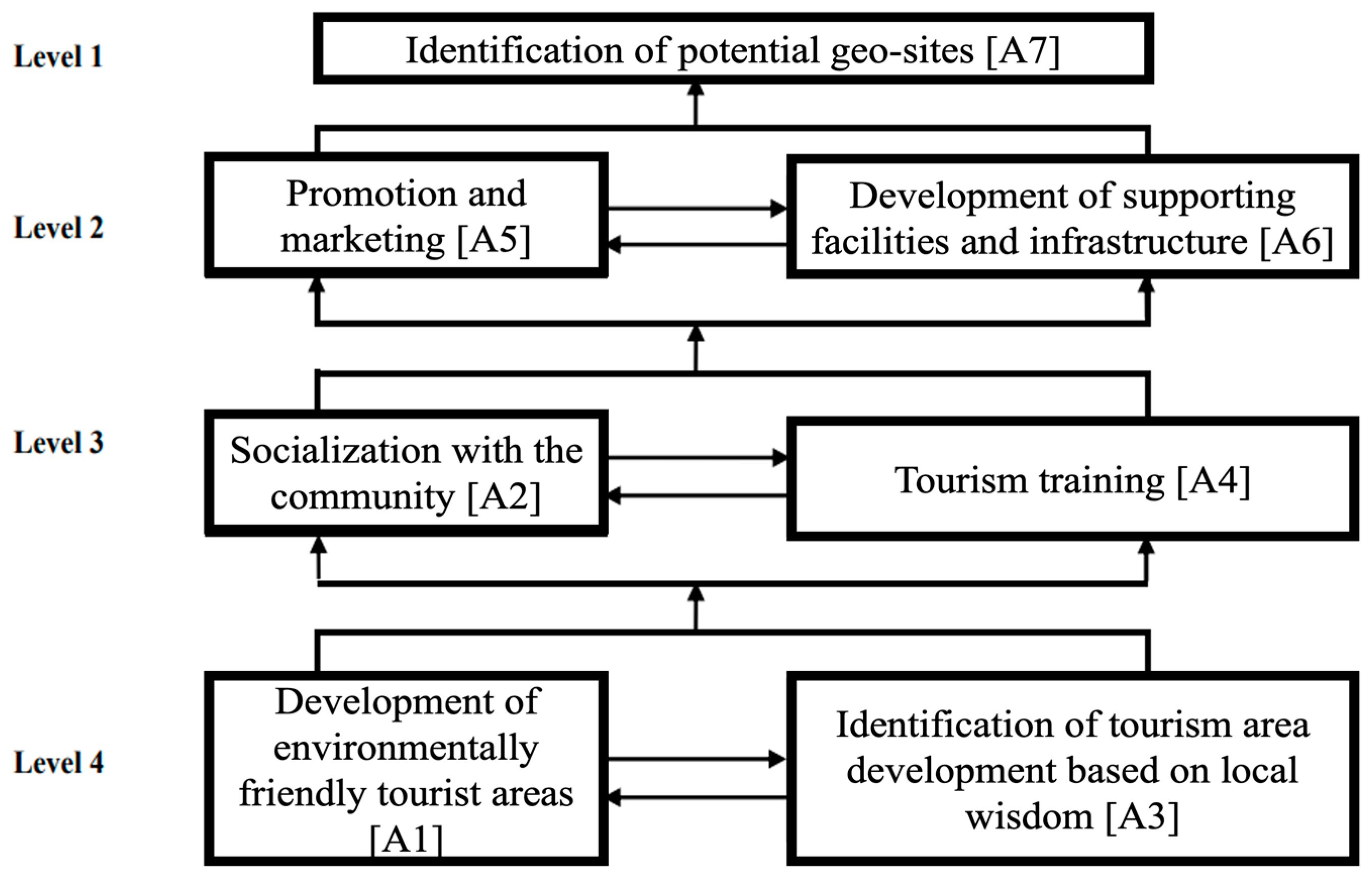

4.2.2. Program Needs

- A1: The development of environmentally friendly tourist areas.

- A2: Socialization with local communities.

- A3: The identification of the development of tourist areas based on local wisdom.

- A4: Tourism training.

- A5: Promotion and marketing.

- A6: The development of supporting facilities and infrastructure.

- A7: The identification of potential geosites.

4.2.3. Program Objectives

- A1: The promotion of integrated regional development.

- A2: The protection or conservation of aquatic ecosystems.

- A3: The encouragement of income-generating activities for local communities and regional governments.

- A4: Increasing local community participation/involvement.

- A5: Connecting with the aspiring Gorontalo geopark.

- A6: Developing or encouraging a sustainable management model for tourism potential.

- A7: Opportunities to invest in the tourism sector.

- A8: Becoming a special-interest tourist attraction.

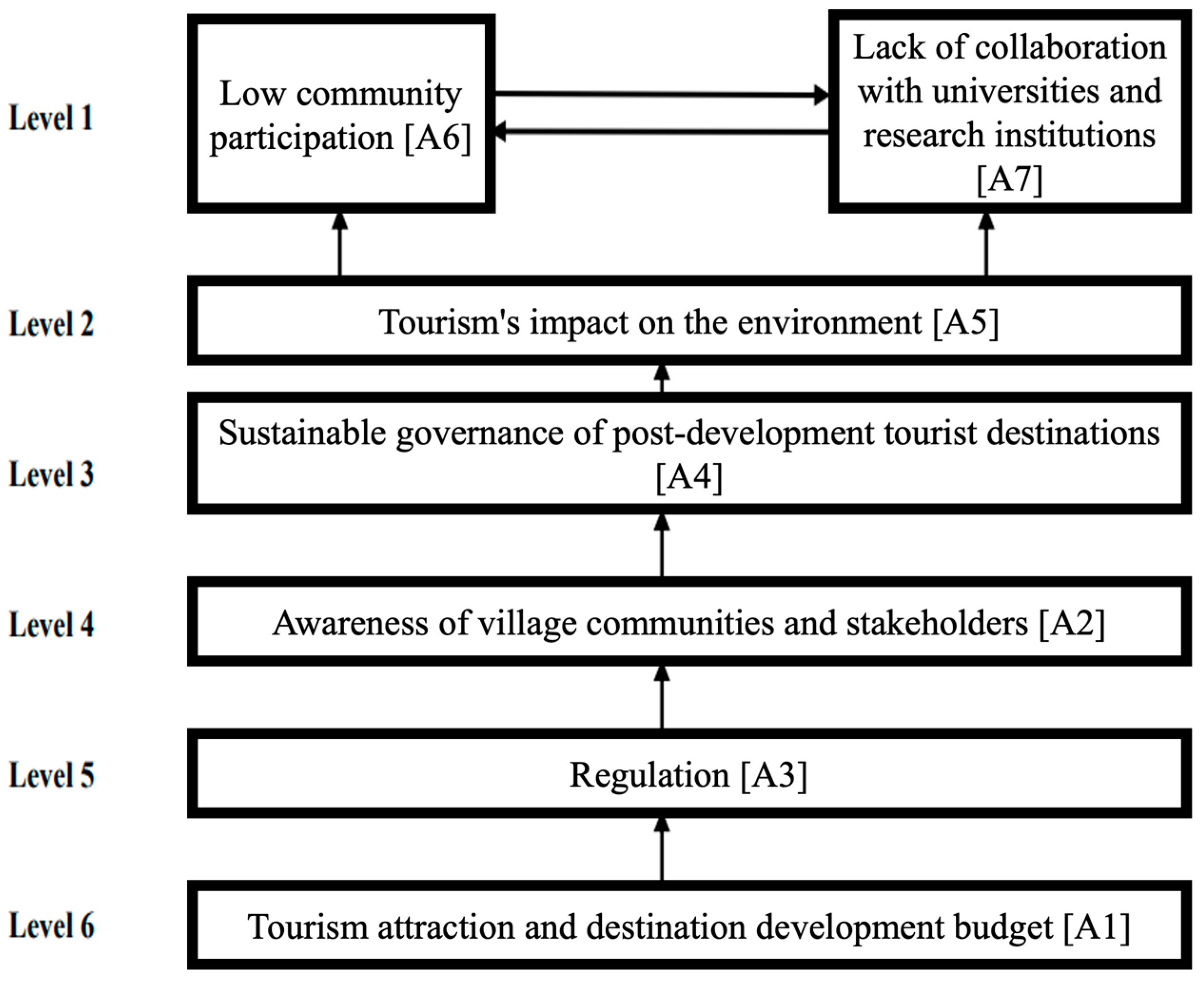

4.2.4. The Main Obstacle

- A1: The budget for developing tourist destinations and attractions.

- A2: The awareness of village communities and stakeholders.

- A3: Regulations.

- A4: The sustainable management of post-development tourist destinations.

- A5: The impact of tourism on the environment.

- A6: Low community participation.

- A7: A lack of collaboration with universities and research institutions.

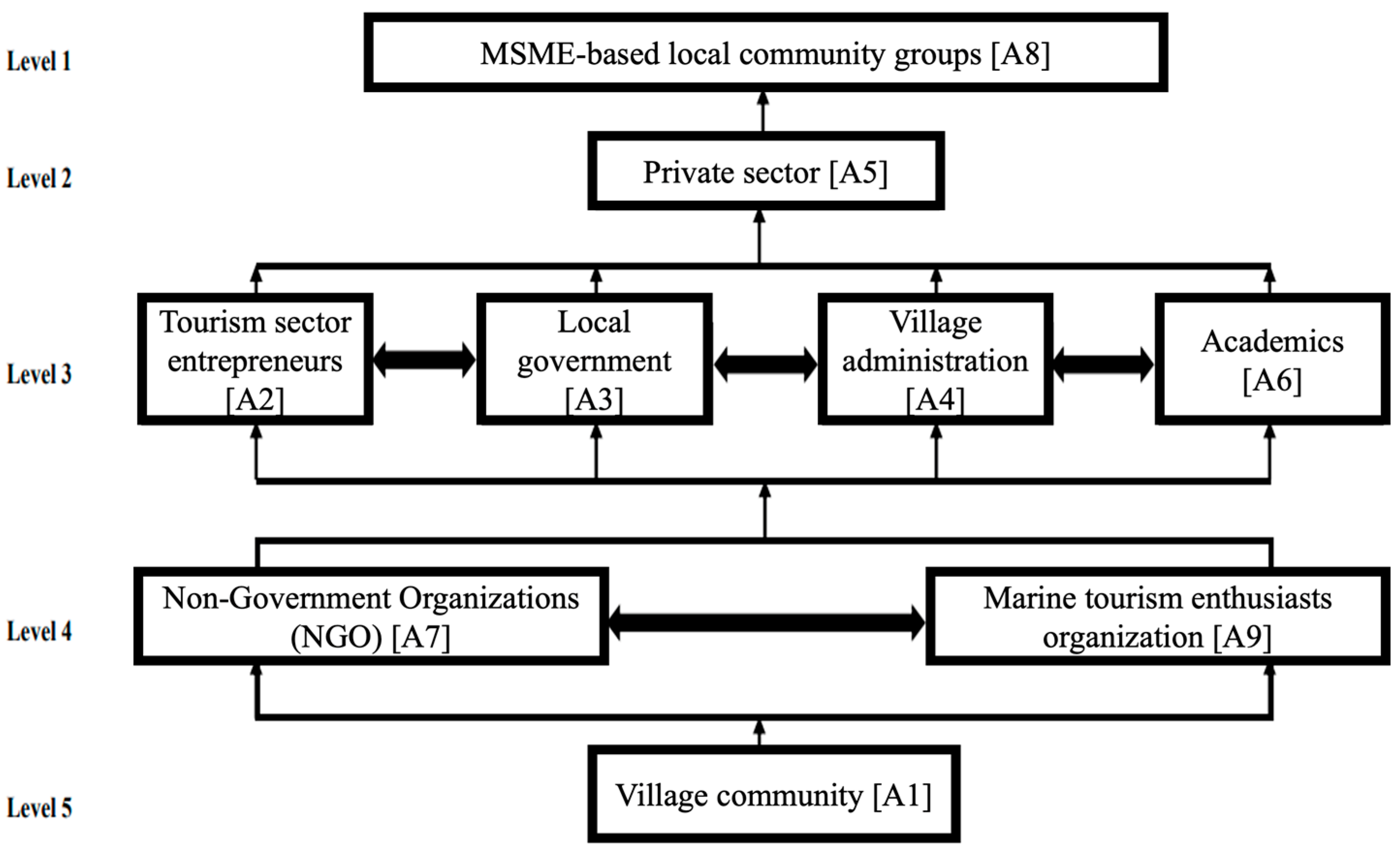

4.2.5. Institutions Involved in Implementing the Program

- A1: The village community.

- A2: Business actors or tourism services.

- A3: The regional government.

- A4: The village government.

- A5: The private sector.

- A6: Academics.

- A7: Non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

- A8: Local community groups activating MSMEs.

- A9: The organization of marine tourism enthusiasts.

5. Discussion

The Proposed Strategy for the Advancement of the Olele Marine Protected Area as a Geotourism Destination, Grounded in the Principles of Integrated Coastal Management (ICM)

- Affected sectors of society:

- A1 (village livelihood).

- A3 (marine tourism activities (diving, snorkeling, etc.)).

- Program needs:

- A3 (the identification of tourism area development based on local wisdom).

- A1 (the development of environmentally friendly tourist areas).

- Program objectives:

- A1 (the promotion of integrated regional development).

- A4 (increasing local community participation/involvement).

- The main obstacle:

- A1 (the budget for developing tourist destinations and attractions).

- A3 (regulation).

- A2 (village community and stakeholder awareness).

- The institutions involved in implementing the program:

- A1 (the village community).

- Recreation both at the beach and at sea.

- Diving tourism in seawater and snorkeling tourism.

- Lodging locations, such as resorts and hotels.

- Glass boats, submarines, surfing, jet skis, and banana boats.

- Ecosystem tourism with fishermen’s tourist boats, island tourism, educational tourism, and fishing tourism.

- Animal tourism, such as seeing turtles, dugongs, whales, dolphins, birds, mammals, and crocodiles.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demolingo, R.H.; Lanya, I.; Paturusi, S.A.; Sunarta, I.N.; Wiweka, K. Strategy for icm-based geotourism development: Case study of the olele marine protected area, indonesia. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 57, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.R. Coastal Zone Management Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.R. Coastal zone management for the new century. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1997, 37, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Ma, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, S. Marine functional zoning: A practical approach for integrated coastal management (ICM) in Xiamen. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 207, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, R.; Fyall, A.; Miller, G. Tourist responses to climate change: Potential impacts and adaptation in Florida’s coastal destinations. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicin-Sain, B. Sustainable development and integrated coastal management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1993, 21, 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicin-Sain, B.; Knecht, R.W.; Jang, D.; Fisk, G.W. Integrated Coastal and Ocean Management: Concepts and Practices; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, B.; Wiweka, K. A study of the tourism area life cycle in Dieng Kulon village. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.; Nickerson, N.; Bosak, K. A Critical Examination Exploring the Differences between Geotourism and Ecotourism. 2016. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/ttra/2009/Abstracts/1/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Ernawati, N.M.; Sitawati, A.A.R.; Muliati, N.K. Batur toward sustainable tourism development-a community-based geotourism case from Bali in Indonesia. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2018, 9, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, R. Meningkatkan Peranserta Masyarakat Desa Olele Dalam Upaya Mendukung Pengembangan Wisata Perdesaan. academia.edu. 2012. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/38390185/Artikel-libre.pdf?1438784938=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DMeningkatkan_Peranserta_Masyarakat_Desa.pdf&Expires=1705829471&Signature=QdQj3IFNEyMKfk2mg2x6CT-4YX1Cb0-mJOxFVK4DbeS9gj~eG6ud5SSknR4EErGkSBF5Uy3Uh5qAWaEus09WFnIfrDT-t7eZHadegz9Al~~374~ApNNHoBFIj7zNeUns-EZ8CxdHKMVYSD-a-uabNLTjt5xxBWVp6IzGHKajP6l0bNkYxOZzXbhPdgsJRSnhXBP3aZ8Cdk3MkS0ZMHJxQk7h4HMCi7sA8l1rNDw1OB9BPaOkOLYSdAFknodXzq57k3w18G48xHfu3dh7W9irVMkvjt~8xaBRCKnghXLljAHGL0h8EfQAdmNYmWjaW9RQqn3525v8dvR2GSOjTU01og__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- White, A.T.; Christie, P.; D’Agnes, H.; Lowry, K.; Milne, N. Designing ICM projects for sustainability: Lessons from the Philippines and Indonesia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2005, 48, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, P.; Kawiana, I.; Suasih, N.; Hartati, P.; Sumadi, N. SWOT and MICMAC analysis to determine the development strategy and sustainability of the Bongkasa Pertiwi Tourism Village, Bali Province, Indonesia. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2020, 9, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheelbeek, P.F.D.; Hamza, Y.A.; Schellenberg, J.; Hill, Z. Improving the use of focus group discussions in low income settings. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, B.; Pai, P.K.; Paul, M. Focus Group Discussion as a Tool to Assess Patient-Based Outcomes, Practical Tips for Conducting Focus Group Discussion for Medical Students—Learning with an Example. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 237437352110342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, J.; Pennink, B. The Essence of Research Methodology: A Concise Guide for Master and Ph.D. Students in Management Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, A. Integrated coastal management in the current regional autonomy law regime in Indonesia: Context of community engagement. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, H.; Marfai, M.A.; Mei, E.T.W. Collaboration practice on ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction in the coastal area of Semarang City, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on LAPAN-IPB Satellite, Bogor, Indonesia, 17–18 September 2019; pp. 469–476. Available online: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/11372/113721F/Collaboration-practice-on-ecosystem-based-disaster-risk-reduction-in-the/10.1117/12.2539059.short (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Damar, A.; Solihin, A.; Kurniawan, F.; Al Amin, M.A. Effectiveness of ICM system and its contribution to local capacity development: Case study in West Papua Province. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1260, 012043. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/1260/1/012043/meta (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Gillgren, C.; Støttrup, J.G.; Schumacher, J.; Dinesen, G.E. Working together: Collaborative decision making for sustainable Integrated Coastal Management (ICM). J. Coast. Conserv. 2019, 23, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumede, M. Integrated Coastal Management (ICM) Governance and its Implementation in South Africa. Afr. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2022, 17, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Boulton, E.; Davey, L.; McEvoy, C. The online survey as a qualitative research tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipta, H. Completion of Matrix Inversions Using Elementary Matrix Inverse Multiplication Method. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2020, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulianti, T.; Sulistyawati, A. Online Focus Group Discussion (OFGD) Model Design in Learning. 2021. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=id&lr=&id=6Hg6EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA226&dq=how+to+conduct+Focus+Group+Discussions+(FGDs)&ots=-eneo1CRpv&sig=yl20aePpcLWstEhyJI1lB0Wxrew (accessed on 25 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K.; Newsome, D. Geotourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.; Newsome, D. Geotourism a global activity. Glob. Geotourism Perspect. 2010, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, G.; Alcalá, L.; Brilha, J.B.; Lantria, L.; Sá, A.; Tourtellot, J. Reflections About the Geotourism Concept; Associação Geoparque Arouca (AGA): Arouca, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. The Scope and Nature of Geotourism. In Geotourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tourtellot, J.B. The Geotourism Approach: An overview of implications and potential effects. Pagine Risposte Tur. 2016, 1–24. Available online: https://www.assoporti.it/sites/www.assoporti.it/files/documenti/Le%20Pagine%20di%20Risposte%20e%20Turismo%202.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Butler, R.W. Tourism carrying capacity research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutakumwa, R.; Mugisha, J.O.; Bernays, S.; Kabunga, E.; Tumwekwase, G.; Mbonye, M.; Seeley, J. Conducting in-depth interviews with and without voice recorders: A comparative analysis. Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deterding, N.M.; Waters, M.C. Flexible Coding of In-depth Interviews: A Twenty-first-century Approach. Sociol. Methods Res. 2021, 50, 708–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, G.; Jain, V.; Ajmera, P.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Modeling and analysing the barriers to the acceptance of energy-efficient appliances using an ISM-DEMATEL approach. J. Model. Manag. 2022, 18, 1809–1833. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JM2-02-2022-0064/full/html (accessed on 6 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ariyani, N.; Fauzi, A. Pathways toward the Transformation of Sustainable Rural Tourism Management in Central Java, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunyowati, D. Integrated Coastal Management: Kajian Hukum untuk Pengelolaan Wilayah Pesisir Berkelanjutan di Indonesia; Airlangga University Press: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dhankher, G.; Ratna, S.; Akhil, D.; Vishwakarma, P.N.; Phanden, R.K.; Singh, M. Impediments to Environmental Sustainability Adoption within Supply Chain of an Indian Nickeling SMEs—An ISM and MICMAC Analysis. In Advances in Industrial and Production Engineering; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Phanden, R.K., Kumar, R., Pandey, P.M., Chakraborty, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 45–53. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-99-1328-2_5 (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Amini, A.; Alimohammadlou, M. Toward equation structural modeling: An integration of interpretive structural modeling and structural equation modeling. J. Manag. Anal. 2021, 8, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, B.; Arief, M.; Hamsal, M.; Furinto, A.; Wiweka, K. The effect of integrated marketing communication on visitor value and its impact on intention to revisit tourist villages: The moderating effect of propensity to travel. Calitatea 2023, 24, 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Budiasa, I.W.; Santosa, I.G.N.; Ambarawati, I.G.A.A.; Suada, I.K.; Sunarta, I.N.; Shchegolkova, N. Feasibility study and carrying capacity of Lake Batur ecosystem to preserve tilapia fish farming in Bali, Indonesia. Biodivers. J. Biol. Divers. 2018, 19, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N. Qualitative research method-phenomenology. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, S.W.; Cahyanto, C. Shipment industry development strategy with interpretative structural modeling (ism) approaches. J. ASRO 2019, 10, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, I.; Molina; Muhani; Karyatun, S.; Dipa, T.; Awaludin; Wiweka, K. Stability and Resilience of Islamic Banking System: A Closer Look at The Macroeconomic Effects. Qual. Access Success 2022, 23, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, S.N.; Paruntu, C.P.; Mingkid, W.M.; Rembet, U.N.; Tumbol, R.A.; Lasabuda, R. Reef fishes community performances in Olele marine tourism area, Bone Bolango Regency, Indonesia. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2020, 13, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, A.; Sancayaningsih, R.P. Diversity, Distribution and Abundance of Scleractinian Coral in District-based Marine Protected Area Olele, Bone Bolango, Gorontalo-Indonesia. KnE Life Sci. 2017, 3, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, H.S. Scrutinizing coastal ecotourism in Gili trawangan, Indonesia. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 7, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahfriliani, L.R.; Sunarsi, D. Perlindungan hukum terhadap perdagangan satwa liar jenis ikan hiu di Indonesia. SUPREMASI J. Huk. 2020, 3, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papilo, P.; Marimin, M.; Hambali, E.; Sitanggang, I.S. Institutional analysis on palm oil-based bioenergy for rural community electricity development in Indonesia: A hybrid of soft system and hard system approach. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2021, 29, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adityanandana, M.; Gerber, J.-F. Post-growth in the tropics? Contestations over Tri Hita Karana and a tourism megaproject in Bali. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1839–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, J.N. Binary matrices in system modeling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1973, SMC-3, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endraswara, S. Memayu Hayuning Bawana: Laku Menuju Keselamatan dan Kebahagiaan Hidup Orang Jawa; Narasi: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2013; ISBN 9789791683159. [Google Scholar]

- Attri, R.; Ashishpal, N.A.; Khan, N.Z.; Siddiquee, A.N.; Khan, Z.A. ISM-MICMAC approach for evaluating the critical success factors of 5S implementation in manufacturing organisations. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2020, 20, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshian, S.; Tavana, M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. From classical interpretive structural modeling to total interpretive structural modeling and beyond: A half-century of business research. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, P.H.; Budiarsa, M.; Wiranatha, A.S. Development Strategy of Budakeling Tourism Village as a Spiritual Tourism Attraction in Karangasem Regency, Bali, Indonesia. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 7, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustandi, A.V. Ulasan Peraturan: Peraturan Menteri Kelautan dan Perikanan No. 3/PERMEN-KP/2018 tentang Tata Cara Perubahan Peruntukan dan Fungsi Zona Inti pada Kawasan Konservasi di Wilayah Pesisir dan Pulau-pulau Kecil untuk Eksploitasi. J. Huk. Lingkung. Indones. 2019, 5, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| No. | Informant | Method of Collecting Data | Number of Informants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGD | Interview | |||

| 1 | Regional revenue agency | √ | √ | 2 |

| 2 | District tourism office | √ | √ | 1 |

| 3 | Provincial tourism office | √ | √ | 1 |

| 4 | Tourism group | √ | √ | 2 |

| 5 | Tourism Village Association | √ | √ | 2 |

| 6 | Local entrepreneurs | √ | √ | 2 |

| 7 | Local community | √ | √ | 3 |

| 8 | Media | √ | √ | 1 |

| 9 | Researchers/academics/NGO representatives (involved in geopark development) | √ | √ | 3 |

| 10 | Association of The Indonesian Tours and Travel Agencies (ASITA) | √ | √ | 1 |

| Elements | Contextual Relationships |

|---|---|

| Affected sectors of society (A1) Program needs (A2) Program objectives (A3) The main obstacle (A4) The institutions involved in implementing the program (A5) | A1i influenced A1j A2i supported A2j A3i contributed to the achievement of A3j A4i caused A4j A5i played a supporting role in A5j |

| Symbol of a Contextual Relationship between Elements i and j (eij) | Definition of Contextual Relationships between Elements (eij) |

|---|---|

| V: | The (i) sub-element of the community sector element affected by its role influenced the (j) sub-element of the community sector element affected by the program. |

| A: | The (j) sub-element of the community sector element affected by the program’s role influenced the (i) sub-element of the program sector. |

| X: | The roles of the (i) sub-element, the jth sub-element, and the (j) sub-element of the community sector elements affected by the program mutually influenced each other in the program. |

| O: | The (i) and (j) sub-elements of the community sector elements affected by the program did not support each other in the program. |

| Sub-Element of the (j) Program Objective | ||

| Sub-Element of the (i) Program Objective |

|

|

| V | |

| ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulistyadi, Y.; Demolingo, R.H.; Latif, B.S.; Indrajaya, T.; Adnyana, P.P.; Wiweka, K. The Implementation of Integrated Coastal Management in the Development of Sustainability-Based Geotourism: A Case Study of Olele, Indonesia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031272

Sulistyadi Y, Demolingo RH, Latif BS, Indrajaya T, Adnyana PP, Wiweka K. The Implementation of Integrated Coastal Management in the Development of Sustainability-Based Geotourism: A Case Study of Olele, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031272

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulistyadi, Yohanes, Ramang H. Demolingo, B. Syarifuddin Latif, Titus Indrajaya, Putu Pramania Adnyana, and Kadek Wiweka. 2024. "The Implementation of Integrated Coastal Management in the Development of Sustainability-Based Geotourism: A Case Study of Olele, Indonesia" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031272

APA StyleSulistyadi, Y., Demolingo, R. H., Latif, B. S., Indrajaya, T., Adnyana, P. P., & Wiweka, K. (2024). The Implementation of Integrated Coastal Management in the Development of Sustainability-Based Geotourism: A Case Study of Olele, Indonesia. Sustainability, 16(3), 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031272