Panel Data Analysis of Subjective Well-Being in European Countries in the Years 2013–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

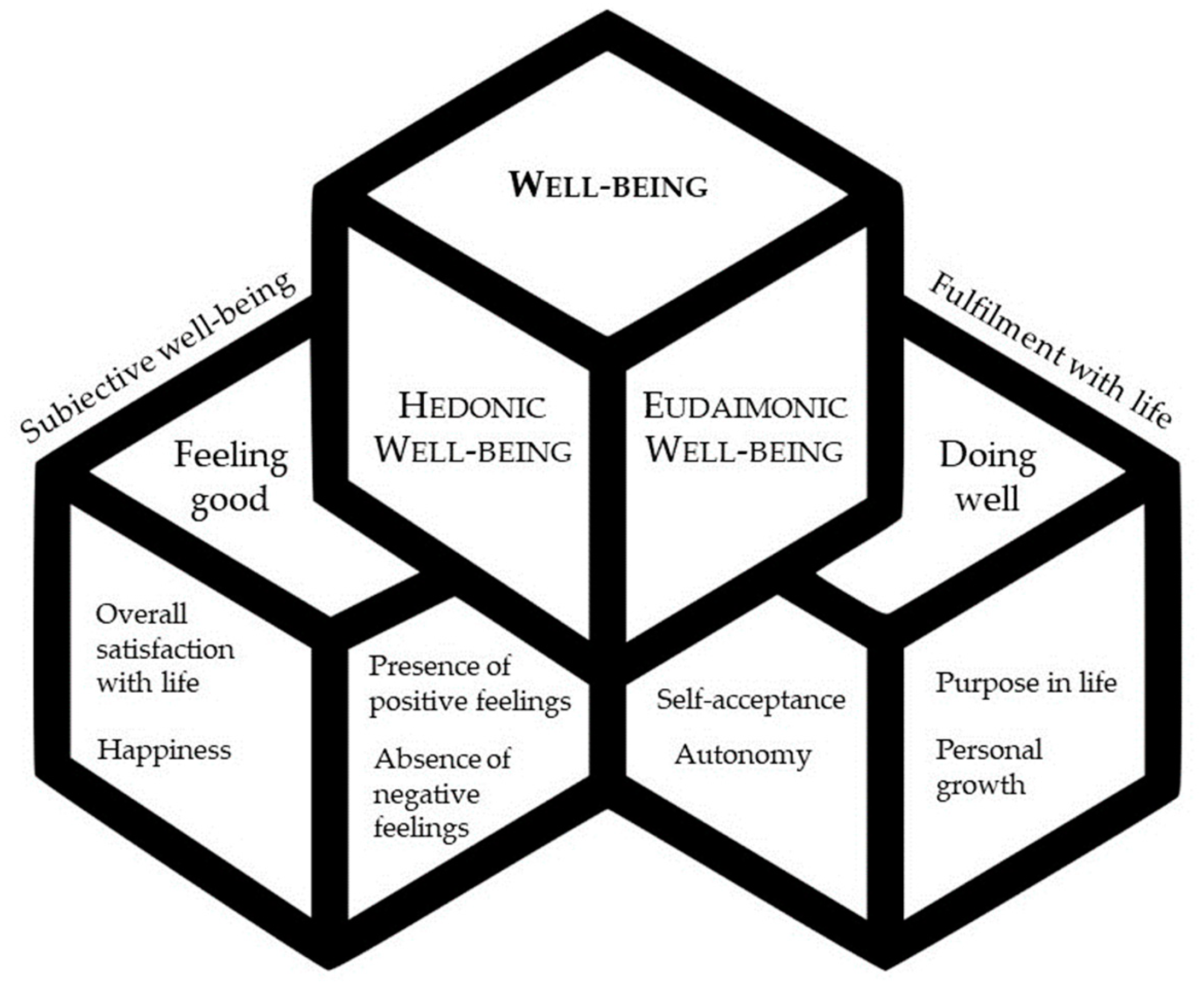

2.1. Subjective Well-Being

2.2. The Easterlin Paradox

3. Materials and Methods

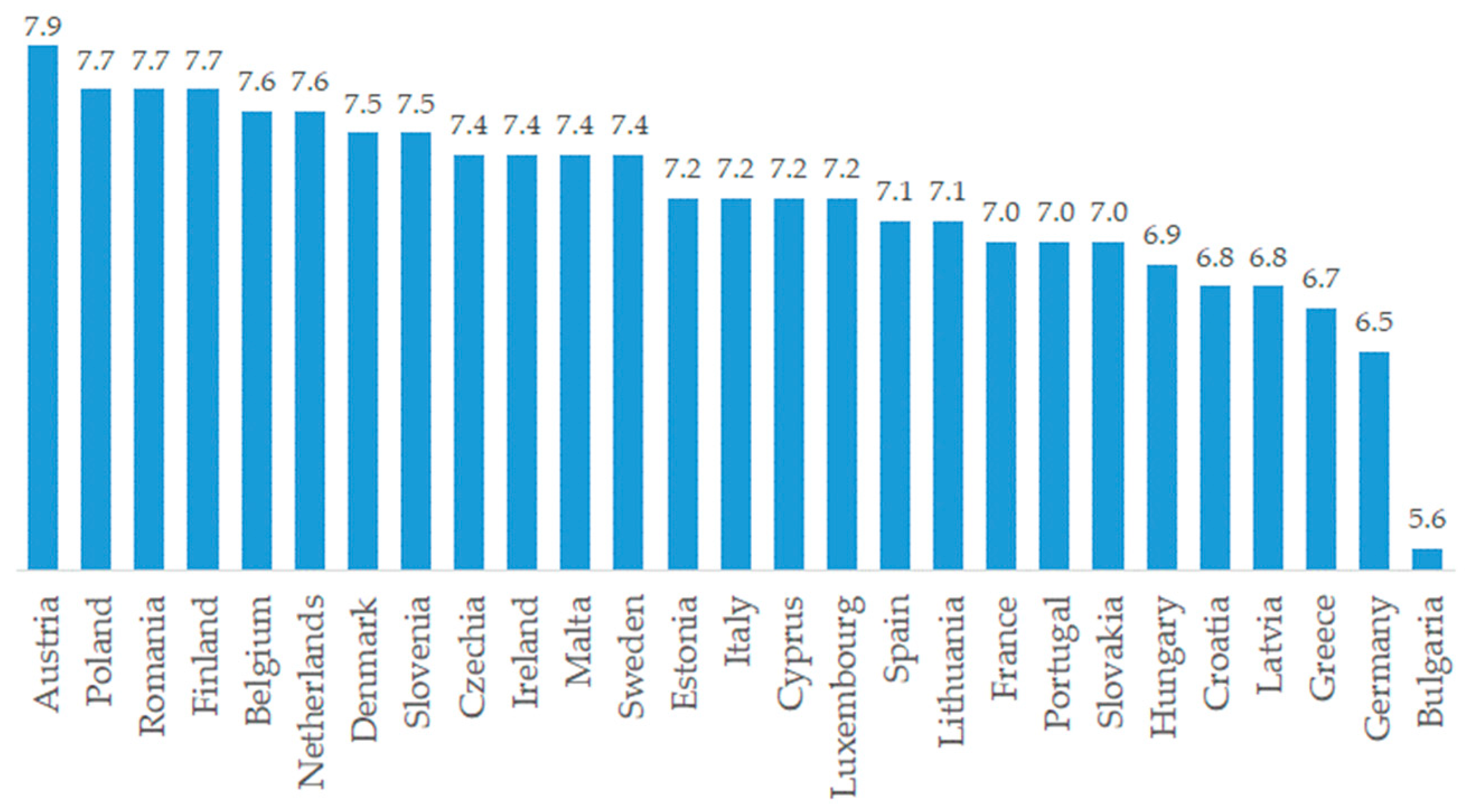

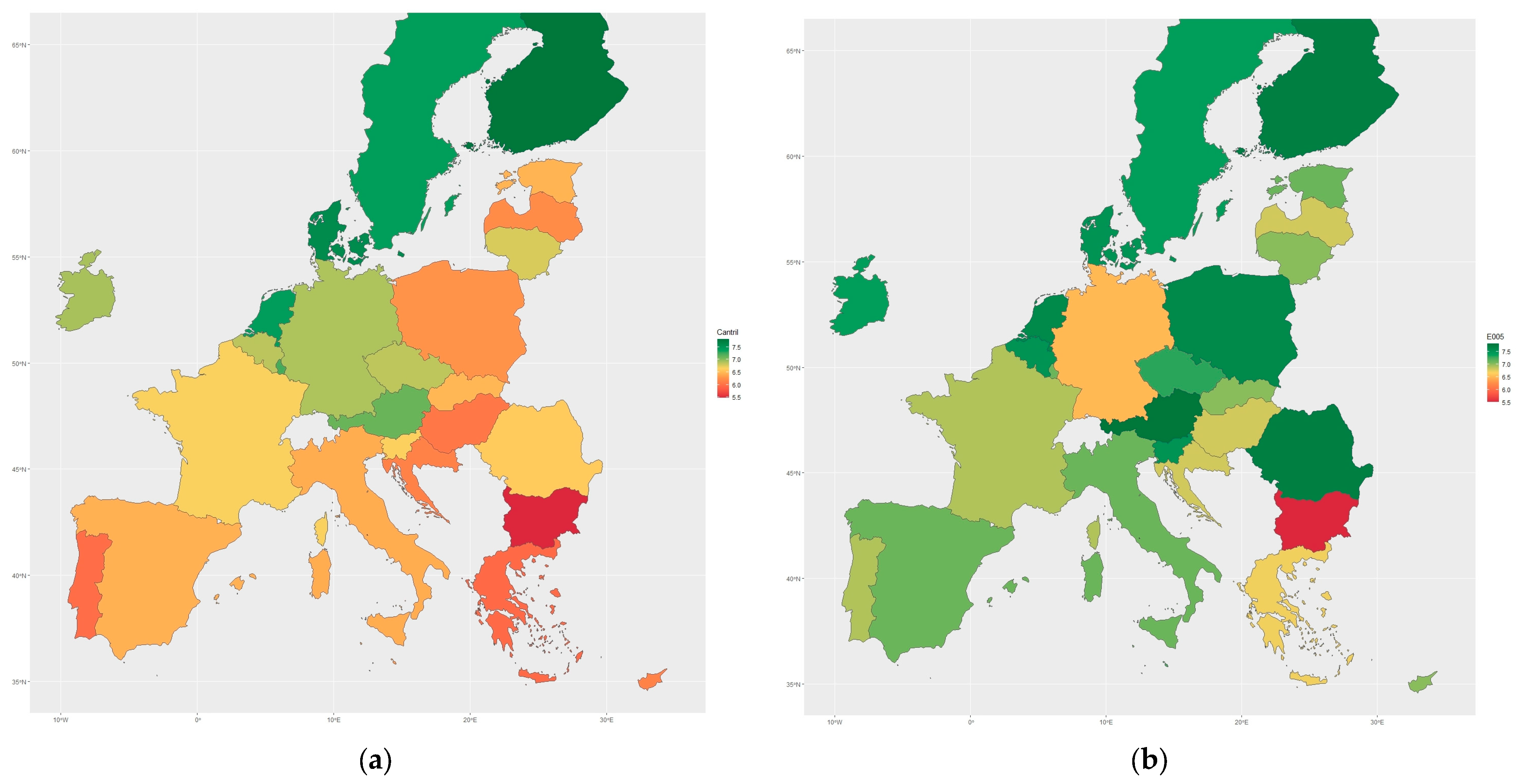

3.1. Data

3.2. Methods of Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Conventional Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)

4.2. The Dynamic Data Envelopment Analysis for Panel Data

5. Discussion and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jarden, A.; Roache, A. What is Well-being? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-SILC. European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/income-and-living-conditions (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Happiness-Cantril-Ladder. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/happiness-cantril-ladder (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Antonelli, M.; De Bonis, V. How Efficient is Welfare for Families? Evidence from European Countries. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenda, A.; Sepe, E.; Scippacercola, S. Efficiency Analysis of Social Protection Expenditure in the Italian Regions. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 73, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Li, T.; Li, L. A Three-Stage DEA-Based Efficiency Evaluation of Social Security Expenditure in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; De Bonis, V. The Efficiency of Social Public Expenditure in European Countries: A Two-Stage Analysis. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kern, M.; Oades, L. Chinese International Students’ Conceptualisations of Well-being. A Prototype Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 939576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadeun-Antuñano, M. Indigenous Perspectives of Well-being. Living a Good Life. In Good Health and Well-Being. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Fernandez, R.M., Leal Filho, W., Wall, T., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, A. Philosophy for the Science of Well-Being, Online ed.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angner, E. The Evolution of Eupathics. The Historical Roots of Subjective Measures of Well-being. Int. J. Well-Being 2011, 1, 4–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). UN, 2006. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Maggino, F.; Zumbo, B. Measuring the Quality of Life and the Construction of Social Indicators. In Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research; Land, K., Michalos, A., Sirgy, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 201–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, J.; Chu, X.; Teng, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, H. Spatio-temporal Analysis of Human Well-being and its Coupling Relationship with Ecosystem Services in Shandong Province, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Doiron, K.; Warren, M.; Donaldson, S. The International Landscape of Positive Psychology Research. A Systematic Review. Int. J. Well-Being 2018, 8, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Oades, L.; Jarden, A. (Eds.) Well-Being, Recovery and Mental Health; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, R.; Maridal, J. A Statistical Meta-analysis of the Well-being Literature. Int. J. Well-Being 2015, 5, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusk, R.; Waters, L. A Psycho-social System Approach to Well-being. Empirically Deriving the Five Domains of Positive Functioning. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarracino, F.; O’Connor, K. A Measure of Well-Being Efficiency Based on the World Happiness Report; GLO Discussion Paper, No. 1061; Global Labor Organization: Essen, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente, E.; Szerb, L.; Acs, Z. Country Level Efficiency and National Systems of Entrepreneurship. A Data Envelopment Analysis Approach. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 1260–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Human Rights and Capabilities. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. The Idea of Justice; Penguin: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, P. Humanizing Development. Taking Stock of Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach. Probl. Desarro. Rev. Latinoam. Econ. 2020, 51, 69586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, P. The Reasoning Agent. Agency in the Capability Approach and some Implications for Development Research and Practice. Iberoam. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 9, 268–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, P. Of Ends and Means. Development Policy Assessment with Human Development and Multiple Causality. Desarro. Soc. 2019, 83, 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Choice, Welfare and Measurement; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.; Glover, J. Women, Culture, and Development. A Study of Human Capabilities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.; Sen, A. (Eds.) The Quality of Life; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner, K. Hedonic versus Eudaimonic Well-Being. How to Reach Happiness. 2023. Available online: https://positivepsychology.com/hedonic-vs-eudaimonic-wellbeing/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Quality of Life Indicators. Overall Experience of Life. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Quality_of_life_indicators_-_overall_experience_of_life (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Wei, Z. Refining the Concept of Eudaimonia. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2023, 4, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, K. What Is Self-Determination Theory? How Self-Determination Influences Motivation. 2022. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-self-determination-theory-2795387 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Hedonism or Eudaimonism. Econation, 2022. Available online: http://econation.one/blog/hedonism-or-eudaimonism/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Hooker, S.; Masters, K.; Ranby, K. Integrating meaning in life and self-determination theory to predict physical activity adoption in previously inactive exercise initiates enrolled in a randomised trial. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 49, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzelman, S. Eudaimonia in the Contemporary Science of Subjective Well-being. Psychological Well-being, Self-determination, and Meaning in Life. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Biswas-Diener, R. Happiness: Unlocking the Mysteries of Psychological Wealth; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. Subjective Measures of Well-being. In Human Well-Being: Studies in Development Economics and Policy; McGillivray, M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, O.; Landhuis, C. Exploring Constructs of Well-being, Happiness and Quality of Life. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, A. Happiness Research. A Review of Critiques. Sociol. Compass 2015, 9, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czapiński, J. Teorie szczęścia w świetle danych z Diagnozy Społecznej. In Diagnoza Społeczna. Warunki i Jakość Życia Polaków; Czapiński, J., Panek, T., Eds.; Rada Monitoringu Społecznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2009; pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.; O’Connor, K. The Easterlin Paradox. In IZA Discussion Paper; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 13923. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R. Happiness and Economic Growth. The Evidence. In IZA Discussion Paper; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 7187, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R. Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? In Essays in Honour of Moses Abramovitz; David, P., Reder, M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Shi, L. Economic Growth and Subjective Well-being. Analysing the Formative Mechanism of Easterlin Paradox. J. Chin. Sociol. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edsel, B. Income Growth and Happiness. Reassessment of the Easterlin Paradox, MPRA. 2014, pp. 1–33. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/53360/1/MPRA_paper_53360.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Coppola, G. The Easterlin Paradox. An Interpretation. J. Happiness Econ. Interpers. Relat. 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clark, A.; Frijters, P.; Shields, M. Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility. An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 95–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Faralla, V. Does Residents’ Perceived Life Satisfaction Vary with Tourist Season? A Two-step Survey in a Mediterranean Destination. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, R.; Shankar, R. Does Good Governance Enhance Happiness. A Cross Nation Study. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 116, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaria, C.; Peroni, C.; Sarracino, F. Happiness matters: Productivity gains from subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Yang, G. A Survey and Analysis of the First 40 Years of Scholarly Literature in DEA: 1978–2016. Recent Developments on the Use of DEA in the Public Sector. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2018, 61, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, L.; Lu, W.; Lin, B. A survey of DEA applications. Omega 2013, 41, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M. Happiness and Life Satisfaction. OurWorldinData. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- OECD. How’s Life? Measuring Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020.

- Helliwell, J.F.; Huang, H.; Norton, M.; Goff, L.; Wang, S. World Happiness Report 2023; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2023/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Measuring Household Wealth through Surveys. In OECD Guidelines for Micro Statistics on Household Wealth; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013.

- World Happiness Report processed by Our World in Data. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the Efficiency of Decision Making Units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Førsund, F. Dynamic Efficiency Measurement. In Benchmarking for Performance Evaluation; Ray, S., Kumbhakar, S., Dua, P., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Førsund, F.; Sarafoglou, N. On the Origins of Data Envelopment Analysis. J. Product. Anal. 2002, 17, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Yang, G.L.; Khoveyni, M.; Michali, M. Data Envelopment Analysis. Recent Developments and Challenges. In The Palgrave Handbook of Operations Research; Salhi, S., Boylan, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, F.; Allahviranloo, T.; Shafiee, M.; Saleh, H. (Eds.) Uncertainty in Data Envelopment Analysis; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karliński, W. Data Envelopment Analysis in Performance Auditing. Kontrola Państwowa 2022, 46, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Son, J.; Kim, C.; Chung, K. Efficiency Measurement Using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) in Public Healthcare. Research Trends from 2017 to 2022. Processes 2023, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smętek, K.; Zawadzka, D.; Strzelecka, A. Examples of the use of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to Assess the Financial Effectiveness of Insurance Companies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 3924–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, S.; Jahanshahloo, G.R.; Lotfi, F.H.; Rostamy-Malkhalifeh, M. Efficiency Measure under Inter-temporal Dependence. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2018, 17, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolszczak-Derlacz, J. An Evaluation and Explanation of (in)efficiency in Higher Education Institutions in Europe and the US with the Application of Two-stage Semi-parametric DEA. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L.; Pesenti, R. Network, Shared Flow and Multi-level DEA Models: A Critical Review. In Data Envelopment Analysis; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer Science+Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 208, pp. 329–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.; Emrouznejad, A.; Lopes, A.L.M.; de Almeida, M.R. Data Envelopment Analysis. Theory and Applications; University Rio Grande do Norte: Rio Grande, OH, USA, 2012; ISBN 978 185449 437 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zubir, M.Z.; Noor, A.A.; Rizal, A.M.; Harith, A.A.; Abas, M.I.; Zakaria, Z.; Bakar, A.F.A. Approach in Inputs & Outputs Selection of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Efficiency Measurement in Hospital. A Systematic Review. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, E.; Kiani, M.M.; Olyaeemanesh, A.; Takian, A.; Majdzadeh, R.; Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, F.; Sharafi, H.; Sajadi, H.S.; Goodarzi, Z.; Noori Hekmat, S. Two-step Estimation of the Impact of Contextual Variables on Technical Efficiency of Hospitals. The Case Study of Public Hospitals in Iran. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Olfati, M.; Pant, M.; Snasel, V. A Review on the 40 Years of Existence of Data Envelopment Analysis Models. Historic Development and Current Trends. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 5397–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezicki, Ł. The Efficiency of Public and Private Higher Education Institutions in Poland. Gospod. Nar. Pol. J. Econ. 2020, 304, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradi, J.; Zhu, H. A Survey on Bank Branch Efficiency and Performance Research with Data Envelopment Analysis. Omega 2013, 41, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Motlagh, A.; Emrouznejad, A. The Origins and Development of Statistical Approaches in Non-parametric Frontier Models. A Survey of the First Two Decades of Scholarly Literature (1998–2020). Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 318, 713–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Cai, Z. An Integrated Slacks-Based Measure of Super-Efficiency with Input Saving and Output Surplus Scaling Factors and its Application in Paper Chemical Mills. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 6161343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah-Fini, S.; Triantis, K.; Johnson, A. Reviewing the Literature on Non-parametric Dynamic Efficiency Measurement. State-of-the-art. J. Product. Anal. 2014, 41, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S. Data Envelopment Analysis: A Non-parametric Method of Production Analysis. In Handbook of Production Economics; Ray, S., Chambers, R., Kumbhakar, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, J. Dynamics of Data Envelopment Analysis. Theory of Systems Efficiency; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State-of-the-Art Information on Data Envelopment Analysis. 2023. Available online: www.deazone.com (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Caves, D.W.; Christensen, L.R.; Diewert, W.E. The economic theory of index numbers and the measurement of input, output, and productivity. Econometrica 1982, 50, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Førsund, F.; Hjalmarsson, L. On the measurement of productive efficiency. Swed. J. Econ. 1974, 76, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Documentation Site. Available online: www.rdocumentation.org (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Malmquist, S. Index Numbers and Indifference Surfaces. Trab. Estad. 1953, 4, 209–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, R.; Akbarian, O.; Banaitis, A.; Soltani, Z. Application of DEA in Benchmarking. A Systematic Literature Review from 2003–2020. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 175–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.; Huang, H.; Grover, S.; Wang, S. Empirical Linkages between Good Governance and National Well-being. J. Comp. Econ. 2018, 46, 1332–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J. Life satisfaction and quality of development. In Policies for Happiness; Bartolini, S., Bilancini, E., Bruni, L., Porta, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Chapter 7; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Moro-Egido, A.; Navarro, M.; Sánchez, A. Changes in Subjective Well-being over Time. Economic and Social Resources do Matter. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2009–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.; Popova, O. Sometimes your best just ain’t good enough: The worldwide evidence on subjective well-being efficiency. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 21, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarracino, F.; O’Connor, K. Economic Growth and Well-being beyond the Easterlin Paradox. In A Modern Guide to the Economics of Happiness; Bruni, L., Smerigli, A., DeRosa, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Drottham, UK, 2021; pp. 162–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mikucka, M.; Sarracino, F.; Dubrow, J. When does Economic Growth Improve Life Satisfaction? Multilevel Analysis of the Roles of Social Trust and Income Inequality in 46 Countries, 1981–2012. World Dev. 2017, 93, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R. Happiness and Economic Growth. The Evidence. In Global Handbook of Quality of Life, International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life; Glatzer, W., Camfield, L., Rojas, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Apeti, A.; Bambe, B.; Lompo, A. Determinants of public sector efficiency: A panel database from a stochastic frontier analysis. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2023, gpad036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Ana, T.D.; Lopes, A.V.; Miranda, R.F.D.A.; Bermejo, P.H.D.S.; Demo, G. Scientific Research on the Efficiency of Public Expenditures. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogere, G.; Makaaru, J. Assessing Public Expenditure Governance: A Conceptual and Analytical Framework. ACODE Policy Res. Ser. 2016, 74, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dutu, R.; Sicari, P. Public Spending Efficiency in the OECD: Benchmarking Health Care, Education, and General Administration. Rev. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 20, 253–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Hahm, H.; Malik, H. Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific 2017. Governance and Fiscal Management; United Nations, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017; ST/ESCAP/2771; pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Baciu, L.; Botezat, A. A Comparative Analysis of the Public Spending Efficiency of the New EU Member States: A DEA Approach. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2014, 50, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. The Quality of Public Expenditures in the EU; European Economy Occasional Papers 125; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Volume 125, pp. 1–66. [CrossRef]

- Dziechciarz, M. Durable Goods Possession and the Determinants of Subjective Well-being of Households. Evidence from Central European Countries. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 2021, 73, 350–360. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, D.; Kim, M.; Lee, K. A Revised Dynamic Data Envelopment Analysis Model with Budget Constraints. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 29, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, M.; Yen, S.; Lim, H. Income and Subjective Well-being. A Case Study. Kaji. Malays. J. Malays. Stud. 2020, 38, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziechciarz, M. Modelling the Influence of Durable Goods Possession on Subjective Well-being of Households. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 2020, 15, 801–812. [Google Scholar]

| Domains | Indicators * |

|---|---|

| Material conditions | |

| Income | Median equivalised net income [EUR per inhabitant] |

| Severe material and social deprivation rate [%] | |

| Arrears on mortgage or rent payments [EUR per inhabitant] | |

| Inability to face unexpected financial expenses [%] | |

| Ability to make ends meet (households making ends meet easily) [%] | |

| Inability to make ends meet (households making ends meet with great difficulty) [%] | |

| Jobs/Productivity | Employment rate by sex [%] |

| Unemployment rate by sex [%] | |

| Long-term unemployment rate [%] Hours worked per week of full-time employment [Hours] | |

| Population and social conditions | |

| Social protection | Social protection expenditures [EUR per inhabitant] |

| Quality of life | |

| Education | Early leavers from education and training by sex [%, 18 to 24 years] |

| Tertiary educational attainment [%] | |

| Environment | Pollution, grime or other environmental problems by degree of urbanisation [%] |

| Health | Healthy life expectancy based on self-perceived health [Years] |

| Self-perceived health [%] | |

| People having a longstanding health problem by the level of activity limitation, sex and age [%] | |

| Self-reported unmet need for medical care by sex (too expensive or too far to travel or waiting list) [%] | |

| Safety | Population reporting occurrence of crime, violence or vandalism in their area by poverty status [%] |

| Subjective well-being and overall experience of life | |

| Life Satisfaction | Average rating of satisfaction overall life satisfaction [rating (0–10)] |

| Cantril ladder score—self-reported life satisfaction [rating (0–10)] | |

| Community/Social Interactions | Persons who cannot afford to get together with friends or family (relatives) for a drink or meal at least once a month by employment status and income quintile [%] Persons who cannot afford to regularly participate in leisure [%] |

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| HHs making ends meet easily [%] | 11.73 (11.92) | 12.10 (11.69) | 12.68 (11.65) | 13.44 (11.50) | 13.73 (10.98) |

| HHs making ends meet with difficulty [%] | 14.54 (10.42) | 13.53 (9.98) | 12.18 (9.53) | 11.26 (9.41) | 9.89 (8.58) |

| Self-perceived health [%] | 67.25 (15.16) | 67.45 (15.34) | 67.66 (14.20) | 67.01 (14.02) | 65.30 (13.66) |

| Healthy life expectancy [Year] | 71.82 (4.83) | 72.21 (4.68) | 72.58 (4.74) | 72.71 (4.59) | 73.39 (4.42) |

| Overall life satisfaction [0–10] | 6.96 (0.73) | 7.06 (0.68) | 7.12 (0.66) | 7.06 (0.68) | 7.12 (0.66) |

| Cantril ladder score [0–10] | 6.24 (0.99) | 6.15 (0.96) | 6.18 (0.86) | 6.25 (0.79) | 6.34 (0.75) |

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| HHs making ends meet easily [%] | 14.53 (10.68) | 15.61 (10.40) | 16.77 (10.67) | 18.00 (10.79) | 15.96 (10.01) |

| HHs making ends meet with difficulty [%] | 9.04 (8.12) | 7.86 (7.65) | 7.57 (7.01) | 6.96 (7.20) | 6.93 (6.80) |

| Self-perceived health [%] | 66.81 (12.80) | 65.93 (13.94) | 64.00 (12.62) | 64.89 (11.53) | 66.76 (11.52) |

| Healthy life expectancy [Year] | 73.62 (4.35) | 73.80 (4.15) | 74.20 (4.13) | 73.90 (3.80) | 73.69 (4.12) |

| Overall life satisfaction [0–10] | 7.17 (0.65) | 7.15 (0.55) | 7.14 (0.51) | 7.14 (0.48) | 7.13 (0.48) |

| Cantril ladder score [0–10] | 6.44 (0.73) | 6.53 (0.69) | 6.58 (0.64) | 6.63 (0.58) | 6.63 (0.56) |

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Median income [EUR per inhabitant] | 13,832.44 (6073.40) | 13,958.85 (5918.07) | 14,466.70 (5999.88) | 15,149.81 (5963.36) | 15,308.15 (5974.20) |

| Social protection benefits [EUR per inhabitant] | 6510.58 (4946.26) | 6650.25 (5122.16) | 6703.23 (5192.85) | 6814.06 (5203.14) | 6927.67 (5213.16) |

| Expenditure on pensions [% of GDP] | 11.00 (2.83) | 11.24 (2.89) | 11.20 (3.01) | 10.97 (3.13) | 10.84 (3.09) |

| Long-term unemployment rate [%] | 5.63 (3.90) | 5.43 (3.89) | 4.93 (3.51) | 4.23 (3.04) | 3.51 (2.74) |

| Employment rate [%] | 67.41 (6.72) | 68.38 (6.38) | 69.43 (6.10) | 70.52 (6.01) | 72.07 (5.77) |

| Tertiary educational attainment [%] | 37.28 (8.64) | 38.83 (8.62) | 39.29 (8.48) | 40.18 (8.47) | 40.83 (8.46) |

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Median income [EUR per inhabitant] | 15,629.22 (5731.63) | 16,321.74 (5645.12) | 16,517.96 (5477.02) | 16,997.07 (5868.67) | 17,818.00 (5892.54) |

| Social protection benefits [EUR per inhabitant] | 7089.83 (5301.15) | 7276.77 (5349.00) | 7553.06 (5434.61) | 8317.52 (5918.57) | 8586.93 (5923.04) |

| Expenditure on pensions [% of GDP] | 10.61 (3.03) | 10.50 (3.02) | 10.43 (3.07) | 11.27 (3.38) | 10.64 (3.18) |

| Long-term unemployment rate [%] | 2.84 (2.43) | 2.37 (2.21) | 2.28 (1.99) | 2.49 (1.85) | 2.14 (1.59) |

| Employment rate [%] | 73.45 (5.70) | 74.37 (5.48) | 73.42 (5.65) | 74.64 (5.16) | 76.38 (4.96) |

| Tertiary educational attainment [%] | 41.65 (8.59) | 42.48 (8.83) | 43.38 (9.18) | 44.58 (9.87) | 44.82 (9.89) |

| Inputs | Indicators |

|---|---|

| I1 | Median equivalised net income [EUR per inhabitant] |

| I2 | Tertiary educational attainment [percentage] |

| I3 | Social protection: benefits [EUR per inhabitant] |

| I4 | Social protection: sickness/healthcare [EUR per inhabitant] |

| I5 | Social protection: sickness/healthcare and disability [EUR per inhabitant] |

| I6 | Social protection expenditures: old age and survivors [EUR per inhabitant] |

| Outputs | |

| O1 | Ability to make ends meet (households making ends meet easily) [percentage] |

| O2 | Cantril ladder score—self-reported life satisfaction [rating (0–10)] |

| Inputs (I) | Outputs (O) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 | I5 | I6 | O1 | O2 | |

| Austria | 23,077.30 | 39.09 | 12,229.98 | 3168.70 | 3954.50 | 5286.52 | 23.10 | 7.18 |

| Belgium | 21,389.80 | 46.55 | 10,947.16 | 3025.06 | 3956.87 | 4313.83 | 29.40 | 6.91 |

| Bulgaria | 7709.30 | 32.60 | 1265.99 | 360.40 | 460.65 | 530.62 | 2.32 | 4.79 |

| Croatia | 9719.20 | 33.42 | 2545.55 | 852.38 | 1127.66 | 1036.50 | 3.34 | 5.64 |

| Cyprus | 17,374.30 | 56.74 | 4644.50 | 963.88 | 1136.59 | 2384.26 | 9.83 | 6.05 |

| Czechia | 12,928.30 | 32.49 | 3461.74 | 1137.99 | 1356.46 | 1495.37 | 11.93 | 6.73 |

| Denmark | 21,438.00 | 45.43 | 15,816.04 | 3403.22 | 5988.08 | 5838.89 | 27.46 | 7.61 |

| Estonia | 12,638.40 | 40.86 | 2887.15 | 834.79 | 1164.96 | 983.58 | 12.97 | 5.85 |

| Finland | 19,940.10 | 40.84 | 12,330.67 | 2875.91 | 4111.39 | 4782.74 | 26.07 | 7.65 |

| France | 20,025.00 | 46.70 | 10,949.15 | 3143.89 | 3842.56 | 4668.56 | 15.68 | 6.60 |

| Germany | 21,697.70 | 32.46 | 11,139.92 | 3683.88 | 4452.50 | 4261.49 | 32.17 | 6.94 |

| Greece | 9454.80 | 41.78 | 4347.78 | 900.88 | 1110.76 | 2857.54 | 1.93 | 5.50 |

| Hungary | 8721.50 | 31.27 | 2313.87 | 637.02 | 783.54 | 1094.30 | 3.62 | 5.57 |

| Ireland | 18,680.90 | 56.25 | 9348.24 | 3584.85 | 4077.03 | 2846.57 | 9.90 | 7.06 |

| Italy | 16,607.70 | 26.66 | 8184.15 | 1892.34 | 2351.09 | 4427.22 | 6.22 | 6.24 |

| Latvia | 9758.40 | 42.47 | 2139.90 | 585.79 | 770.33 | 864.10 | 6.38 | 5.75 |

| Lithuania | 10,501.20 | 55.11 | 2363.87 | 706.30 | 912.42 | 888.46 | 5.08 | 6.09 |

| Luxembourg | 29,350.90 | 54.81 | 20,653.79 | 5382.24 | 7913.24 | 7176.24 | 28.36 | 7.09 |

| Malta | 17,783.70 | 36.92 | 3975.37 | 1321.13 | 1468.9 | 1759.36 | 13.72 | 6.44 |

| Netherlands | 21,541.20 | 48.52 | 12,115.11 | 4197.58 | 5247.66 | 4626.84 | 41.20 | 7.43 |

| Poland | 11,658.60 | 42.52 | 2484.84 | 586.40 | 752.66 | 1310.67 | 8.82 | 6.04 |

| Portugal | 11,129.90 | 36.98 | 4548.12 | 1164.05 | 1490.24 | 2414.84 | 8.01 | 5.57 |

| Romania | 6234.10 | 24.90 | 1421.58 | 394.34 | 484.75 | 684.13 | 4.24 | 5.90 |

| Slovakia | 9924.30 | 35.33 | 2794.79 | 884.84 | 1123.64 | 1123.82 | 4.38 | 6.17 |

| Slovenia | 15,990.00 | 42.91 | 4817.65 | 1600.17 | 1857.04 | 2104.93 | 14.36 | 6.15 |

| Spain | 15,619.40 | 44.46 | 6001.10 | 1635.08 | 2051.44 | 2734.74 | 14.63 | 6.43 |

| Sweden | 20,305.90 | 47.90 | 13,255.77 | 3546.36 | 4895.17 | 5345.11 | 25.15 | 7.35 |

| 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | 2021 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRS | CRS | VRS | CRS | VRS | CRS | VRS | CRS | |

| Belgium | 1.043 | 1.147 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.030 | 1.086 | 1.031 | 1.047 |

| Bulgaria | 1.000 | 1.124 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Czechia | 1.000 | 1.034 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Denmark | 1.000 | 1.205 | 1.002 | 1.002 | 1.009 | 1.136 | 1.017 | 1.167 |

| Germany | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Estonia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Ireland | 1.008 | 1.733 | 1.014 | 1.014 | 1.023 | 1.672 | 1.029 | 1.567 |

| Greece | 1.125 | 1.745 | 1.186 | 1.186 | 1.165 | 1.478 | 1.114 | 1.245 |

| Spain | 1.070 | 1.425 | 1.092 | 1.092 | 1.114 | 1.218 | 1.047 | 1.062 |

| France | 1.125 | 1.577 | 1.151 | 1.151 | 1.150 | 1.628 | 1.114 | 1.169 |

| Croatia | 1.096 | 1.225 | 1.184 | 1.184 | 1.179 | 1.549 | 1.086 | 1.388 |

| Italy | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.030 | 1.030 | 1.001 | 1.022 | 1.063 | 1.123 |

| Cyprus | 1.118 | 1.488 | 1.115 | 1.115 | 1.056 | 1.315 | 1.086 | 1.342 |

| Latvia | 1.021 | 1.090 | 1.030 | 1.030 | 1.033 | 1.051 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Lithuania | 1.007 | 1.345 | 1.030 | 1.030 | 1.018 | 1.257 | 1.020 | 1.197 |

| Luxembourg | 1.088 | 1.604 | 1.095 | 1.095 | 1.041 | 1.374 | 1.041 | 1.565 |

| Hungary | 1.152 | 1.362 | 1.112 | 1.112 | 1.060 | 1.221 | 1.082 | 1.225 |

| Malta | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.048 | 1.147 |

| Netherlands | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Austria | 1.023 | 1.244 | 1.048 | 1.048 | 1.065 | 1.242 | 1.077 | 1.199 |

| Poland | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Portugal | 1.249 | 1.432 | 1.211 | 1.211 | 1.127 | 1.346 | 1.046 | 1.071 |

| Romania | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Slovenia | 1.165 | 1.461 | 1.136 | 1.136 | 1.106 | 1.271 | 1.004 | 1.085 |

| Slovakia | 1.015 | 1.127 | 1.036 | 1.036 | 1.035 | 1.396 | 1.027 | 1.101 |

| Finland | 1.000 | 1.104 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.070 | 1.000 | 1.017 |

| Sweden | 1.022 | 1.386 | 1.034 | 1.034 | 1.043 | 1.146 | 1.057 | 1.214 |

| Country | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 0.892 | 0.889 | 0.872 | 0.929 | 0.990 | 0.992 | 0.921 | 0.931 | 0.955 | 0.890 |

| Bulgaria | 0.934 | 0.885 | 0.889 | 0.962 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Czechia | 0.994 | 1 | 0.967 | 0.970 | 0.895 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Denmark | 0.876 | 0.833 | 0.830 | 0.829 | 0.888 | 0.887 | 0.880 | 0.876 | 0.857 | 0.880 |

| Germany | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Estonia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ireland | 0.619 | 0.637 | 0.577 | 0.550 | 0.554 | 0.531 | 0.598 | 0.610 | 0.638 | 0.622 |

| Greece | 0.734 | 0.604 | 0.573 | 0.543 | 0.543 | 0.591 | 0.677 | 0.708 | 0.803 | 0.832 |

| Spain | 0.739 | 0.708 | 0.702 | 0.729 | 0.784 | 0.745 | 0.821 | 1 | 0.942 | 0.988 |

| France | 0.626 | 0.661 | 0.634 | 0.628 | 0.637 | 0.597 | 0.614 | 0.764 | 0.855 | 0.835 |

| Croatia | 0.950 | 0.855 | 0.817 | 0.687 | 0.701 | 0.629 | 0.646 | 0.667 | 0.720 | 0.759 |

| Italy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.994 | 0.961 | 0.923 | 0.978 | 0.956 | 0.891 | 0.828 |

| Cyprus | 0.584 | 0.585 | 0.672 | 0.531 | 0.659 | 0.792 | 0.761 | 0.934 | 0.745 | 0.845 |

| Latvia | 0.736 | 0.728 | 0.917 | 0.860 | 0.790 | 0.923 | 0.951 | 0.937 | 1 | 0.880 |

| Lithuania | 0.769 | 0.826 | 0.744 | 0.773 | 0.756 | 0.833 | 0.795 | 0.800 | 0.835 | 0.926 |

| Luxembourg | 0.674 | 0.626 | 0.624 | 0.664 | 0.616 | 0.645 | 0.728 | 0.682 | 0.639 | 0.518 |

| Hungary | 0.728 | 0.727 | 0.734 | 0.746 | 0.801 | 0.772 | 0.819 | 0.791 | 0.816 | 0.986 |

| Malta | 0.851 | 0.870 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.956 | 0.872 | 0.709 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Austria | 1 | 0.827 | 0.804 | 0.802 | 0.827 | 0.829 | 0.805 | 0.811 | 0.834 | 0.787 |

| Poland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.863 |

| Portugal | 0.758 | 0.753 | 0.698 | 0.674 | 0.690 | 0.708 | 0.743 | 0.830 | 0.934 | 0.891 |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Slovenia | 0.720 | 0.739 | 0.684 | 0.770 | 0.802 | 0.861 | 0.787 | 0.840 | 0.922 | 0.917 |

| Slovakia | 0.878 | 0.960 | 0.888 | 0.779 | 0.759 | 0.714 | 0.717 | 0.819 | 0.908 | 1 |

| Finland | 0.953 | 0.881 | 0.906 | 0.914 | 0.908 | 0.967 | 0.934 | 0.927 | 0.983 | 1 |

| Sweden | 0.7412 | 0.7413 | 0.7216 | 0.7822 | 0.8443 | 0.8545 | 0.8729 | 0.8801 | 0.8235 | 0.9344 |

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC | EC | TC |

| Belgium | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| Bulgaria | 0.95 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.90 |

| Czechia | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.93 |

| Denmark | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.94 |

| Germany | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.91 |

| Estonia | 1.00 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| Ireland | 1.03 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.13 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.91 |

| Greece | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 1.14 | 0.86 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.88 |

| Spain | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.22 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.87 |

| France | 1.06 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.24 | 0.99 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.92 |

| Croatia | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.88 |

| Italy | 1.00 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| Cyprus | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 0.84 |

| Latvia | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 0.88 | 0.91 |

| Lithuania | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 0.92 |

| Luxembourg | 0.93 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.13 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.95 |

| Hungary | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 0.89 |

| Malta | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.93 |

| Netherlands | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Austria | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| Poland | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| Portugal | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.12 | 0.97 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.90 |

| Romania | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| Slovenia | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.13 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.86 |

| Slovakia | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.11 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 0.88 |

| Finland | 0.92 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.95 |

| Sweden | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 1.13 | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dziechciarz, M. Panel Data Analysis of Subjective Well-Being in European Countries in the Years 2013–2022. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052124

Dziechciarz M. Panel Data Analysis of Subjective Well-Being in European Countries in the Years 2013–2022. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052124

Chicago/Turabian StyleDziechciarz, Marta. 2024. "Panel Data Analysis of Subjective Well-Being in European Countries in the Years 2013–2022" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052124

APA StyleDziechciarz, M. (2024). Panel Data Analysis of Subjective Well-Being in European Countries in the Years 2013–2022. Sustainability, 16(5), 2124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052124