Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Proposal for a Comparative Indicator-Based Framework in European Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

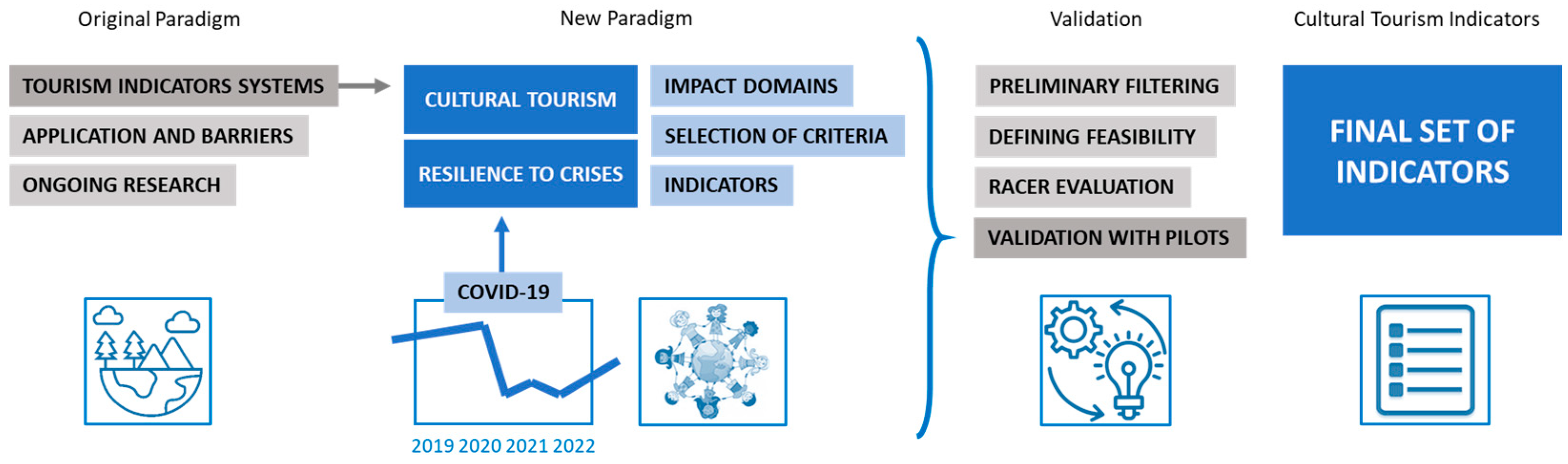

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Research Methodology

3. Results: IMPACTOUR Comparative Assessment Framework

3.1. General Domains

3.2. Proposed Impact Domains

3.2.1. Characterization Domain

- Size: Aiming to understand the overall dimensions of the site in terms of understanding the location and its population concentration.

- Cultural resilience relevance: Identifying the types of cultural facilities as well as the official recognition of existing cultural resources.

- Organization/destination management: Identifying characteristics related to the seasonality of tourism, as well as management and marketing strategies aiming at better-informed tourists who understand the impacts of their activities.

- Connectivity and accessibility: Aiming at understanding how cultural resources are connected to local and regional transport services, and understanding the extent to which destinations can cater for visitors with physical, sensory, or cognitive impairments, in terms of provision of infrastructure, facilities, and services that can be used equitably by visitors and the local community.

3.2.2. Resilience Domain

- Adaptation to crises or sudden events: How the global changes in tourism trends (related to crises of all types: economic, hazard-related, climate change, overtourism, etc.) may affect the tourism and transportation sectors.

- Recovery measures. Aiming to understand the tools, strategies, or plans that a site may use to contend with adverse conditions and recover during and after crises.

- Digitalization: Fostering digitalization as the main resilience booster. This can be considered as a recovery measure itself, aiming to be the main driver of the site’s management in the future.

3.2.3. Environmental Domain

- Environmental quality: Understanding the impact that cultural tourism activities have in terms of public noise, traffic disturbances, or site pollution.

- Environmental awareness: Identifying how local activities are directly related to landscape and biodiversity protection, promoting campaigns of environmental awareness, and/or preparing to meet requirements regarding nature preservation.

- Carbon footprint: Aiming to address the ecological impact of local production and the promotion of sustainable practices.

- Water usage: Effects that tourism has on drinking-water management.

- Energy usage: Energy sustainability of the destination.

- Waste management: Recycling and reuse practices or policies specifically related to landscape protection.

- Reducing transport impacts: Aiming at identifying the implementation of sustainable policies in terms of public transport, bikes, footpaths, or low-carbon modes of transport.

3.2.4. Economic Domain

- Cultural tourism flow at the destination: Addressing the tourist flow (arrivals and length of stays) as a general precondition for economic impacts.

- Direct economic impact from the cultural tourists: Related to direct consumption by the tourists, generally measurable by the daily spending per tourist/visitor.

- Cultural tourism enterprise(s) performance: Aiming to address the actual weight and strength of the tourist sector and enterprises. The current employment in cultural tourism-related activities, turnover, and added value generated by the cultural tourism enterprises, as well as wage information, would make it possible to evaluate the competitiveness and sustainability of the cultural tourism sector. Since seasonality is a challenge in many locations, this could be analyzed based on the occupancy rate per month and the average for the year.

- Clustering and innovation: Related to the innovativeness of cultural tourism companies. Systemic interactions between businesses and other actors lead to virtuous economic development [53]. Clustering and innovation by looking at the collaborations with R&D actors and other industries, as well as the investments into new technologies directed towards cultural tourism.

3.2.5. Social Domain

- Balance of population: Monitoring the coexistence between residents and visitors.

- Quality of life: Aiming to improve the quality of life of residents.

- Cultural responsibility: Assuring the maintenance and safeguarding of inherited values and traditional ways of life.

- Social inclusion: Aiming to measure the accessibility of tourist information and the universal accessibility of cultural tourism attractions.

- Intercultural: Monitoring the capacity to attract and entertain visitors despite their origins or abilities.

3.2.6. Cultural Domain

- Cultural heritage preservation: Measuring and minimizing the impact that tourists have on the integrity of the cultural heritage and its unique values. Also, understanding how tourists degrade or impact those material or immaterial values, or whether tourism activities help in heritage preservation.

- Cultural tourism promotion: Aiming to reveal the way in which a destination is organized to host and represent tourism and make the impact sustainable in all ways. This criterion monitors the need for diversification and marketing strategies for cultural tourism at pilot destinations, and it also indicates the need to ensure more accessible and equitable websites and promotion products. Its goal is to better promote cultural tourism while upholding the hospitality levels of the destinations.

- Management/protection plans: Aiming to know the traditional and innovative methods that the destination must use to attract tourists and manage the site. It addresses the need for better-focused governance strategies, plans, and actions for more hospitable cultural tourism at destinations.

3.3. Validation of the Domains and Indicators with the Pilot Community

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions/Do You Have Information Regarding… | Positive Answers |

|---|---|

| … the resilience of your site against COVID-19 crisis? | |

| Social distancing impact upon religious and cultural festivals calculated | 5 |

| Change in domestic cultural tourism visitors’ numbers (domestic vs. international…) | 11 |

| Number of inhabitants visiting local attractions | 9 |

| % of shift to digital online visits | 6 |

| Income from digital tourists/online visits | 2 |

| Public sectors’ participation in financing the response to COVID-19 (e.g., employment support, operating costs, other grants or loans to businesses) | 9 |

| Public sectors’ support in dealing with small scale services with business and bureaucratic issues due to COVID-19 | 7 |

| Number of complaints from businesses due to COVID-19 measures | 5 |

| Percentage of employments affected by the pandemic in the cultural tourism sector (reduction of salaries or unemployed people) | 7 |

| … data related to cultural tourism in your destination? | |

| Visitors attractions (or Cultural Tourism sites) with cultural or language barriers (such as the use or not of English, or any other foreign language different to the native one, at the destination) | 7 |

| Number of cultural attractions that tourists visit (average) in the destination (compared, or not, to total visits). | 8 |

| Use that tourists make of the digital offer of your site (% that buy on-line tickets, % that use tourism apps, …) | 3 |

| The number of second homes in your destination | 10 |

| Number of residents employed in tourism sector | 12 |

| Number of residents employed in cultural tourism sector | 6 |

| Number of residents volunteering in tourism attractions and events | 5 |

| Residents’ perception on tourism | 7 |

| Visitor attractions (or cultural tourism sites) accessible for people with physical disability (ramps, elevators…) | 14 |

| Visitor attractions (or cultural tourism sites) accessible for people with sensory disabilities (sight, hearing… audio/video-guides, tactile info, etc.) | 9 |

| Visitor attractions with digital content offer | 10 |

| % of digital offer accessible for people with sensory disabilities | 4 |

| Number of cultural events celebrated per year (Including concerts, exhibitions, theatre…) | 16 |

| Number of attendees per event | 10 |

| % of the tourists on your destination with high cultural tourism motivation | 11 |

| … cultural heritage of your destination? | |

| Public funding spent in restoration of historic buildings | 10 |

| Private funding spent in restoration of historic buildings | 4 |

| Number of restored buildings | 8 |

| Number of listed or protected tangible or intangible cultural heritage | 10 |

| Donations and sponsorship for cultural heritage attractions or events | 4 |

| Number of residents volunteering in cultural heritage protection, management… | 4 |

| Number of heritage buildings/cultural attractions in risk due to overtourism? | 1 |

| … environmental data in your destination? | |

| Number of environmental or cultural awareness activities promoted by museums, heritage interpretation centres or other cultural attractions in destination | 8 |

| Percentage of annual amount of energy consumed from renewable sources compared to overall energy consumption at destination level per year | 3 |

| Percentage of local or environmentally friendly materials for buildings renovation | 1 |

| … these data? | |

| Energy consumption per night/per person (in each season, month…) | 2 |

| Water consumption per night/per person | 1 |

| Waste produced per night/per person | 1 |

| Waste recycled per year/per person | 1 |

| Daily spending per tourist/visitor | 7 |

| … the number of tourism companies in your destination which? | |

| Separate different types of waste | 9 |

| Take actions to reduce water consumption | 3 |

| Use recycled water | 2 |

| Take actions to reduce energy consumption | 3 |

| Use renewable sources | 3 |

| Use a voluntary certification/labelling of sustainability measures | 3 |

| Use a voluntary accessibility information certification/labelling scheme | 5 |

| Contribute to cultural heritage protection or restoration | 5 |

| Actively support protection, conservation and management of local biodiversity and landscapes | 3 |

| … tourism companies? | |

| Number of tourism companies (restaurants, accommodations…) who use local products (zero miles food/“Km0”/“locavorism”/local food supply chain) | 10 |

| Has a woman as a general manager | 8 |

| Average wage in tourism sector, and wage differentials between men and women | 3 |

| Average wage in tourism sector per economic field (e.g., hotels, restaurants, museums, etc.), and for men/women | 5 |

| Age ranges of employees in tourism sector | 5 |

| Number of tourism enterprises per type of services provided (transport, accommodation, tours, etc.) | 9 |

| Employment in tourism enterprises per type of services provided | 6 |

| Value added generated by the cultural tourism enterprises (per field of activity) | 1 |

| Percentage of employments affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in the Cultural Tourism sector (reduction of salaries or unemployed people) | 3 |

| … local overnight accommodation? | |

| Arrivals and nights spent at commercial accommodation establishments (all types) | 11 |

| Commercial accommodations that are accessible to disabled people | 9 |

| Arrivals and nights spent at sharing/collaborative economy accommodation establishments | 4 |

| Occupancy rate in commercial accommodation per month and average for the year | 9 |

| Occupancy rate in sharing/collaborative economy accommodation establishments | 4 |

| …transport companies (public or private), which…? | |

| Transport modes that are accessible to disabled people | 7 |

| % of transport fleet powered by electricity per type of transport | 2 |

| … your destination products? | |

| ECO or BIO label/certification | 6 |

| Number of sales of ECO/BIO products | 4 |

| Number of sales of zero miles-kms food products | 3 |

| % of sales of local made souvenirs | 4 |

Appendix B

| Characterization Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Size | A1.1 | Total population |

| A1.2 | Population density | |

| Cultural tourism relevance | A2.1 | Percentage of cultural tourists (compared to the total number of tourists) |

| A2.2 | Number of listed tangible or intangible cultural heritage | |

| A2.3 | Number of other EU heritage/natural labels | |

| A2.4 | Number and type of cultural facilities, museums, exhibition halls, theatres, monuments | |

| Organization/destination Management | A3.1 | Percentage of dispersed cultural tourism attractions |

| A3.2 | Percentage of key sites operating all year | |

| A3.3 | Destination management organization (DMO) | |

| Connectivity | A4.1 | Connectivity to site (passenger flights + by road + by rail + boat/cruise) |

| RESILIENCE INDICATORS | ||

| Adaptation to crises or sudden events | B1.1 | Cultural tourism income decrease in a year affected by an external event (pandemic/climate events/economic crisis) |

| B1.2 | Percentage of employments affected by emergencies/external factors in the cultural tourism sector | |

| B1.3 | Tourist infrastructure in zones vulnerable to climate change/environmental hazards | |

| Recovery measures | B2.1 | Public sectors’ participation in financing the response to emergencies/external factors (e.g., employment support, operating costs, other grants or loans to businesses) |

| B2.2 | Existing contingency and/or recovery plans (vulnerability against hazards or others) | |

| B2.3 | Diversification strategies/plans for tourists’ masses or sudden tourism growth | |

| B2.4 | Tools for tourists’ masses or sudden tourism growth (real-time monitoring of tourism flow, carrying capacity, etc.) | |

| B2.5 | Percentage of tourists per type of origin (local/national/international/etc.) | |

| Digitalization | B3.1 | Public sectors’ participation in financing the response to emergencies/external factors (e.g., employment support, operating costs, other grants or loans to businesses) |

| Environmental Indicators | ||

| Environmental quality | C1.1 | Rate of noise, light/air pollution, or traffic disturbance complaints per 100 inhabitants |

| Environmental awareness | C2.1 | Percentage of local enterprises in the tourism sector actively supporting the conservation of local biodiversity and landscapes |

| C2.2 | Percentage of tourism sector enterprises whose main focus is environmental awareness (museums, shops, etc.) | |

| Carbon footprint | C3.1 | Local products with any kind of local, national, or international ecological label (ECO/BIO/KM0 labels) |

| Water usage | C4.1 | Number of days per year where there are water supply shortages |

| Reducing transport impacts | C5.1 | Percentage of cultural touristic disperse attractions connected by public transport |

| C5.2 | Percentage of total cultural touristic attractions accessible by bike or scooter | |

| Economic Indicators | ||

| Cultural tourism flow at destination | D1.1 | Average nights spent at tourist accommodation establishments |

| D1.2 | Average nights spent at shared/collaborative economy accommodation establishments | |

| Direct economic impact from the cultural tourists | D2.1 | Average daily spending per tourist/visitor |

| Cultural tourism enterprise(s) performance | D3.1 | Employment in cultural tourism activities |

| D3.2 | Occupancy rate in commercial accommodation per month, and average for the year | |

| D3.3 | Occupancy rate in shared/collaborative economy accommodation establishments | |

| D3.4 | Turnover per cultural tourism activity | |

| Social Indicators | ||

| Balance of population | E1.1 | Number of tourists/visitors per 100 residents |

| E1.2 | Tourism pressure on residents | |

| E1.3 | Percentage of residents employed in tourism | |

| Cultural responsibility | E2.1 | Percentage of volunteering at cultural tourism sites/attractions |

| E2.2 | Local availability of traditional skills | |

| E2.3 | Responsibility share (public/private) for cultural tourism sites | |

| Social inclusion | E3.1 | Availability of free/discounted/educational access to key sites for locals |

| E3.2 | Accessibility plan: physical, mental, visual, etc. | |

| Interculturality | E4.1 | Cultural tourism for defined social purposes: pilgrimages, folk or religious festivals, etc. |

| E4.2 | Accessible multilingual directions to venue; signage and interpretation at venue | |

| Cultural Indicators | ||

| Cultural heritage preservation | F1.1 | Degradation on buildings/sites by usage/massification (include if they are listed as endangered sites) |

| F1.2 | Tourism’s contribution to the protection and restoration of historic buildings/sites in the tourist area | |

| F1.3 | Percentage of funding of public and private finance spent on the improvement of the physical urban environment over the total amount | |

| F1.4 | Visual impacts | |

| F1.5 | Percentage of restored historic buildings and sites | |

| Cultural heritage promotion | F2.1 | Promotion of cultural activities (museums, festivals, traditional events, local culture, guided tours, publications, etc.) and attendees per activity/event/year |

| F2.2 | Alternative cultural attractions (considering the surrounding area or territory near to the destination) | |

| F2.3 | Number of cultural attractions that tourists visit (average) in the destination (compared to total visits) | |

References

- Mathisen, L.; Søreng, S.; Lyrek, T. The reciprocity of soil, soul and society: The heart of developing regenerative tourism activities. J. Tour. Futur. 2022, 8, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture: A Driver and an Enabler of Sustainable Development. Thematic Think Piece: 2012; 10p. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Think%20Pieces/2_culture.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Potts, A. European Cultural Heritage Green Paper “Putting Europe’s Shared Heritage at the Heart of the European Green Deal”; Europa Nostra: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dupeyras, A.; Maccallum, N. Indicators for Measuring Competitiveness in Tourism: A Guidance Document; OECD Tourism Papers, 2013/02; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Report on Tourism and Culture Synergies; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, D.S.; Rizzo, I. Economics of cultural tourism: Issues and perspectives. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvet, T.; Olesk, M.; Tiits, M.; Raun, J. Innovative Tools for Tourism and Cultural Tourism Impact Assessment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism Definitions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A. Managing Tourism at World Heritaga Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2002; 96p. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP; UNWTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2005; ISBN 978-92-807-2507-0. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SCT OMC Working Group Sustainable Cultural Tourism Open Method of Coordination. Available online: https://www.culturaltourism-network.eu/ (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Cleere, H. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (2005). In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 2720–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission EU Delivering on the UN 2030 Agenda. 2019, pp. 1–4. Available online: https://openresearch.amsterdam/image/2022/9/22/factsheet_eu_delivering_2030_agenda_sustainable_development_en_0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Inclusive Recovery Guide—Sociocultural Impacts of COVID-19, Issue 2: Cultural Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A.; Bocean, C.G.; Cazacu, M. Rethinking tourism industry in pandemic COVID-19 period. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Indicator of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destination: A Guidebook; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2004; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Internal Market Industry Entrepreneurship and SMEs. The European Tourism Indicator System—ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; ISBN 978-92-79-55249-6. [Google Scholar]

- GSTC. GSTC Destination Criteria. Glob. Sustain. Tour. Counc. 2019, 1–17. Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/GSTC-Destination-Criteria-v2.0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Montalto, V.; Tacao Moura, C.; Panella, F.; Alberti, V.; Becker, W.; Saisana, M. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor: 2019 Edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halatsis, A.; Munoz, A. Sustainable Cruise Tourism Certification System. SIROCCO Project D3.4.1. 2017. Available online: https://sirocco.interreg-med.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Sites/Sustainable_Tourism/Projects/SIROCCO/SIROCCO_D3.4.1.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Coccossis, H.; Koutsopoulou, A. Building a Common Approach in Tourism Sustainability Evaluation, CO-EVOLVE Project D3.16.1. 2017.

- MITOMED+ Tourism Data Indicators Toolkit. Models of Integrated Tourism in the MEDiterranean Plus 2017–2020. Project Deliverable. Toolbox 2020. Available online: https://mitomed-plus.interreg-med.eu/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Robinson, M.; Picard, D. Tourism, Culture and Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 54, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Ethos, T.C.; Heritage, C. International Cultural Tourism Charter, Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1999; 5p. [Google Scholar]

- London, A. Cultural Tourism Resources. 2010, pp. 5–7. Available online: https://www.culturehive.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Cultural-Tourism-Definitions-resource-1.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Tudorache, D.M.; Simon, T.; Frenţ, C.; Musteaţă-Pavel, M. Difficulties and challenges in applying the European Tourism Indicators System (ETIS) for sustainable tourist destinations: The case of Braşov county in the Romanian Carpathians. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.; Capocchi, A.; Foroni, I.; Zenga, M. An assessment of the implementation of the European tourism indicator system for sustainable destinations in Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, D.; Luis Nicolau, J. How does culture influence a Country’s travel and tourism competitiveness? A longitudinal frontier study on 39 countries. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polukhina, A.; Sheresheva, M.; Efremova, M.; Suranova, O.; Agalakova, O.; Antonov-Ovseenko, A. The Concept of Sustainable Rural Tourism Development in the Face of COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Russia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarchuk, O.; Barr, J.C.; Cozzio, C. How much is too much? Estimating tourism carrying capacity in urban context using sentiment analysis. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Rethinking Cultural Tourism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futur. 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Oyola, M.; Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism indicators as planning tools in cultural destinations. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.V.; Truong, T.T.K.; Duong, L.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Dao, G.V.H.; Dao, C.N. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on tourism business in a developing city: Insight from Vietnam. Economies 2021, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Grochowicz, M.; Pawlusiński, R. How a tourism city responds to COVID-19: A cee perspective (kraków case study). Sustainability 2021, 13, 7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Zubiaga, M.; Gandini, A.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S. Systemic innovation areas for heritage-led rural regeneration: A multilevel repository of best practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey and the World Travel & Tourism Council. Managing Overcrowding Tourism Destinations; McKinsey & Company: Hong Kong, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; Research for TRAN Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 1–255. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Shen, L.; Wong, S.W.; Cheng, G.; Shu, T. A “load-carrier” perspective approach for assessing tourism resource carrying capacity. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Tourism and Transport in 2020 and beyond; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Expert Network on Culture and Audiovisual (EENCA). Carrying Capacity at Sensitive Cultural Heritage Sites; EENCA: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A.; Femenia-Serra, F.; Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Giner-Sánchez, D. Measuring the progress of smart destinations: The use of indicators as a management tool. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Experiences from Pilot Studies in Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Tourism Policy Responses to the Coronavirus (COVID-19); OECD: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Helble, M.; Fink, A. Reviving Tourism amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. ADB Briefs 2020, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Eppich, R.; Grinda, J.L.G. Management documentation indicators & good practice at cultural heritage places. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci.—ISPRS Arch. 2015, 40, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BirdLife. International Monitoring and Indicators; BirdLife: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. Impacts of climate change knowledge on coastal tourists’ destination decision-making and revisit intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvet, T.; Olesk, M.; Tiits, M. Report on Cultural Tourism Leading to Sustainable Economic and Social Development; IMPACTOUR Deliverable 1.1: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Pires, S.; Fidélis, T.; Ramos, T.B. Measuring and comparing local sustainable development through common indicators: Constraints and achievements in practice. Cities 2014, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.; Chen, X.; Garrison, S.; Shaddock, J. Introduction: The Impact of (COVID)-19 on Cultural Tourism. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2023, 23, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Fernandes, C. Cultural Tourism During the (COVID)-19 Pandemic in Portugal. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2022, 23, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xie, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Han, T. How digitalization promotes the sustainable integration of culture and tourism for economic recovery. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 988–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, T.; Trišić, I.; Brđanin, E.; Štetić, S.; Nechita, F.; Candrea, A.N. Natural and Sociocultural Values of a Tourism Destination in the Function of Sustainable Tourism Development—An Example of a Protected Area. Sustainability 2024, 16, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelmagd, D. Sustainable urbanism and cultural tourism, the case of the Sphinx Avenue, Luxor. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 71, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trišić, I.; Privitera, D.; Ristić, V.; Štetić, S.; Stanić Jovanović, S.; Nechita, F. Measuring Residents’; and Visitors’ Satisfaction with Sustainable Tourism—The Case of “Rusanda” Nature Park, Vojvodina Province. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Dealing with Crises | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Managing tourism growth and overcrowding in tourism destinations | Provides relevant recommendations regarding the negative impacts that overtourism has at all levels in a community; and proposes strategies and policy recommendations to address it. | [40] |

| Provides an overlook of the problems at overcrowded destinations, coping with tourism’s success. | [41] | |

| Focuses on the policy response to impacts on tourism management. | [42] | |

| Introduces an evaluation methodology to identify overloaded or underutilized destinations and thereby deploy action to address potential risks. | [43] | |

| Digitalization and smart management of carrying capacity in tourism destinations | Analyzes the impact of the pandemic in the tourism transportation sector and promotes smart management for sustainable and diversified tourism flows, based on measurement and tools. | [44] |

| Identifies the definition of the carrying capacity of destinations as a prior step to making recommendations and implementing actions to tackle mass tourism. | [45] | |

| Analyzes how the availability of behavioral data and mobile technologies can help not only to reduce crowds but also to improve queue management. This encourages destinations to embrace smart tourism. | [46] | |

| Underlines the lack of empirical data obtained from a broader representative sample before, during, and after the pandemic. | [31] | |

| Rethinking and sustainably reviving tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic | Includes experiences measuring the sustainability of tourism and gives touches on analyzing how COVID-19 has impacted the data development of sustainable tourism policies. | [47] |

| Analyzes the travel restrictions during the pandemic and looks forward to diversifying tourism markets, including tools for stimulating demand, encouraging innovation, and rethinking the tourism sector. | [48] | |

| Introduces measures to revive the tourism sector during the pandemic. It mentions fostering domestic tourism and travel bubbles. | [49] | |

| Provides a set of recommendations to face the pandemic and develops a whole chapter on cultural tourism. Proposes recommendations for social and cultural recovery from COVID-19. | [15] | |

| Analyzes the effects of the pandemic on tourism economics and lists a synthesis of measures that may enable ensuring the resilience of the tourism sector. | [16] | |

| Shows how the theory and practice of cultural tourism have undergone significant transformation, reflecting on cultural tourism as a dynamic social practice, analyzing the cultural, mobility, performative, creative, and curatorial turns. | [33] |

| Source | Characterization (or Management) | Resilience | Environmental | Economic and Social | Social and Cultural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Socioeconomic | Sociocultural | Social and Cultural Separated | ||||

| UNWTO | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| ETIS | x | x | x | x | |||

| GSTC-DC | x | x | x | x | |||

| CCCM | x | x | x | x | |||

| Authors | x | x | x | x | x | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zubiaga, M.; Sopelana, A.; Gandini, A.; Aliaga, H.M.; Kalvet, T. Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Proposal for a Comparative Indicator-Based Framework in European Destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052062

Zubiaga M, Sopelana A, Gandini A, Aliaga HM, Kalvet T. Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Proposal for a Comparative Indicator-Based Framework in European Destinations. Sustainability. 2024; 16(5):2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052062

Chicago/Turabian StyleZubiaga, Mikel, Amaia Sopelana, Alessandra Gandini, Héctor M. Aliaga, and Tarmo Kalvet. 2024. "Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Proposal for a Comparative Indicator-Based Framework in European Destinations" Sustainability 16, no. 5: 2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052062

APA StyleZubiaga, M., Sopelana, A., Gandini, A., Aliaga, H. M., & Kalvet, T. (2024). Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Proposal for a Comparative Indicator-Based Framework in European Destinations. Sustainability, 16(5), 2062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16052062