1. Introduction

Like many developing countries in Southeast Asia and across the globe, Indonesia is, we argue, at a crossroads. On the one hand, recurring economic inequality and internal pressures have driven the Indonesian government to bring economic development to the Outer Islands of Indonesia, a term Clifford Geertz [

1] used to refer to the islands other than Java, the most populated island in the country and one in which development has been unequally focused on for centuries. Within the past 10 years, development projects such as the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) in Papua [

2], the plan to move the capital city to Kalimantan (under the banner of Ibukota Nusantara, IKN) [

3], Food Estate projects in Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua [

4], as well as the rapid development of oil palm plantations in these three large islands [

5] have, thus, significantly transformed the islands’ landscapes and brought repercussions to the social and ecological lives within.

On the other hand, climate crises and international pressures have now pushed the Indonesian government to take all the necessary means to conserve its vast, yet degraded, tropical ecosystems. Based on the 2022 data from Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry (Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan, KLHK), the country has over 96 million ha of forest (or covering 51.2% of its land), with around 6 million ha of forest loss between 2000 and 2020 [

6]. However, the rate of deforestation has successfully been reduced in recent years, and the net deforestation between 2021 and 2022 reached its lowest point in over 30 years [

7]. This success has been partially credited to the social forestry program that started in 2014.

The social forestry program was founded on the fact that of more than 14 million households involved in smallholder agriculture in Indonesia (based on the latest agricultural census), about 9.2 million households live within, and depend on, the forest area [

6]. These smallholder farmers manage less than 0.5 ha of land as a means of livelihood but significantly help to shape the structure of Indonesia’s agriculture and food (agrifood) systems [

8]. The fact that forests are the source of livelihood for these forest-dependent communities in Indonesia lends to the erroneous view that these communities also contribute to the lingering pressures [

9]. To address this problem, the Indonesian government implemented various initiatives to build a stronger legal framework as well as promote community-based conservation and social forestry, which conceptually seek to encourage community participation in forest management through better agricultural practice and agroforestry schemes [

10,

11].

Over the last decades, conservation initiatives have indeed been characterized by a shift from a top-down government approach toward a bottom-up community development program and devolution of natural resource management to local communities [

10]. This shift is built on the premise that local communities are the custodians of biodiversity in local ecosystems. Their well-being will, therefore, determine the extent to which natural resources can be conserved. The shift from fence conservation (which is based on the strict closing and ‘fencing’ of the conservation area) to market- and community-based conservation has been seen in social forestry (and similar approaches), increasingly adopted as an environmental conservation effort [

12,

13,

14,

15].

There is, however, a criticism of this particular view of a conservation approach. In seeing this, we refer to the work of Rob Fletcher on environmentality [

16,

17]. Inspired by Foucault’s governmentality and Agrawal’s similar approach [

18,

19], Fletcher argues that there has been a continuous shift in the conservation paradigm over the last century or so. The early approach to conservation was termed sovereign environmentality, which sees compliance to forest conservation via top-down injunctions, through approaches such as fences. In Indonesia, this has been practiced since the Dutch colonial era up to the 1980s [

20]. This shifted into a form of disciplinary environmentality when a community-based conservation approach gained prominence through international donors and projects. This form of environmentality understands that forest-dependent communities are “enjoined to internalize particular norms and values by means of which they become compelled to self-regulate” [

17] (p. 312). This is exemplified, for instance, by how the phrase ‘community-based’ has often been abused to impose external conservation values, often from academics and policymakers, onto the communities.

Fletcher later unravels a new approach of ‘market-based mechanisms’ in conservation, by which forest resources are commodified to generate income for smallholder farmers, which tends to help incentivize their sustainable utilization [

12,

21]. This grew into prominence in the 2000s, and has arguably continued to the present, through a reevaluation of international grants and government policy, including, in this case, the social forestry program. This recent shift to neoliberal environmentality, as Fletcher puts it, is subject to criticism as this reduces forest to market value and puts forest-dependent communities into a capitalistic locked-in trap [

22].

Although many have argued that social forestry and market-based conservation are a potential win-win for conservation and livelihoods, these initiatives are typically defined by a dominant focus on external market-led incentives, downplaying the role of local and marginalized economies. Studies have also extensively evaluated this approach based on their linkages between conservation impacts and sustainable livelihoods, and these evaluations have shown mixed results [

23,

24]. One notable series of publications in Sumatra and Kalimantan [

10,

11,

25] compare the social and ecological impacts of community-based conservation practices in Hutan Desa (village forest) with adjacent sites that do not implement this approach, which shows that while both the conservation impact and community well-being have indeed transpired, the results have been varied, wherein the two have not been necessarily connected. The failure to account for local ecological, cultural, and social contexts, we argue, hinders the achievement of livelihood and conservation outcomes.

It is also important to note that smallholder farmers in Indonesia (as it is in Southeast Asia), particularly around forest areas, typically do not rely on a single commodity but diversify their crops as a strategy for risk mitigation [

26]. Most smallholder farmers rely on a subsistence economy, whereby farming is practiced first and foremost to fulfill their daily needs, be it through direct consumption or via a market mechanism [

27]. A subsistence economy enables households to build a diversity of livelihoods and be adaptive to the dynamics of the larger socio-economic contexts [

28]. This practice, however, has often been deemed backward, vulnerable, and unproductive, which then engenders the government and NGOs alike to push toward a more promising economy for the smallholders through cash crops and a better linkage to the global value chains [

21,

29]. The situation, as some critics argue, inadvertently creates a precarious state for these farmers who are now dependent on the volatility of international prices and strategies of multi-national lead firms [

22,

30]. Studies have also shown that local food systems that are linked to livelihood diversification, including non-farm labor, have the potential to provide food security and meaningful livelihoods for local populations in a more sustainable way than commercial agriculture linked to the global economy, so long as the larger economic, institutional, and political contexts are in support of their local livelihood [

30,

31].

While we argue that emphasizing the potential contribution of diverse local agrifood systems that link to conservation and livelihoods is critical, we do not necessarily see global value chains and the market economy as a capitalistic system that traps smallholder farmers in a vulnerable state. On the contrary, studies have shown that although the power relations shaped by the lead firms often left farmers at the receiving end of the value chain without a strong bargaining position, the latter’s linkage to the market economy should be seen as a way to establish a livelihood strategy of their own [

31,

32]. Neilson refers to the idea of fortress farming [

33], whereby cash crops are used as a fortress against adversity, while smallholders maintain their daily economy through subsistence farming and other available means.

Understanding the relationships between income diversity and conservation implies something more than just imposing a livelihood strategy on smallholder farmers. It requires us (academics, governments, NGOs) to look beyond the capitalistic economy (or its singular counter-narrative) and see a diverse set of economies intertwined with each other, including the emerging discourse of alternative economies [

34]. In doing so, this paper uses the diverse economies approach as advocated by Gibson-Graham in their seminal work on The End of Capitalism (as we knew it) [

35]. ‘Diverse economies’ is a political project of seeing beyond the dichotomy of capitalistic and non-capitalistic systems, by acknowledging that there is a spectrum in which different economic approaches (market/alternative market/non-market, wage/alternative paid/non-paid, capitalist/alternative capitalist/non-capitalist) are distributed. Employing a diverse economies approach enables us to see the intermingling of different modes of economy, livelihoods, and agrifood systems as a multiplicity [

36] rather than contesting views. As a feminist economy in origin, the diverse economies approach puts the focus on the invisible; those that perform non-capitalistic economies as the backbone for the functioning of our society (family care, housework, gift giving, etc.). To quote the work of Gibson-Graham [

37] (p. 618),

“It is here that we confront a choice: to continue to marginalize (by ignoring or disparaging) the plethora of hidden and alternative economic activities that contribute to social well-being and environmental regeneration, or to make them the focus of our research and teaching in order to make them more ‘real’, more credible, more viable as objects of policy and activism, more present as everyday realities that touch all our lives and dynamically shape our futures.”

While this diverse economies approach has been extensively used in the case of alternative food networks [

38,

39], public health [

40], and community work in urban areas [

38], there are fewer studies on how this approach can be implemented in conservation and livelihood (although see [

41]). In the context of conservation, this approach shifts our view from merely opting between differing approaches to the conservation–livelihood nexus toward providing a space of possibility for forest-dependent communities to build their livelihood strategy in accordance with conservation goals. This is particularly pressing when the choice of one economic approach (e.g., market-based economy) hinders the continuity of another (e.g., subsistence economy).

This view leads us to what Fletcher offers in his thesis: a new form of liberation environmentality. Liberation environmentality refers to a form of environmental governance that is distinct from other top-down conservation approaches (government-based and incentive-based). Instead, the interests of conservation and development actors are aligned with the goals and aspirations of local community groups, promoting social and environmental justice, and emphasizing “… genuinely participatory and collaborative processes for enhancing people’s well-being within culturally appropriate frames” [

16] (p. 178). The goal, in Fletcher’s terms, is “to champion democratic, egalitarian, and non-hierarchical forms of natural resource management in which local people enjoy a genuinely participatory (if not self-mobilizing) role” (p. 178). What comes after the liberation environmentality and diverse economies is an ethics of care—one that acknowledges different worldviews and brings the marginalized to the foreground [

42,

43].

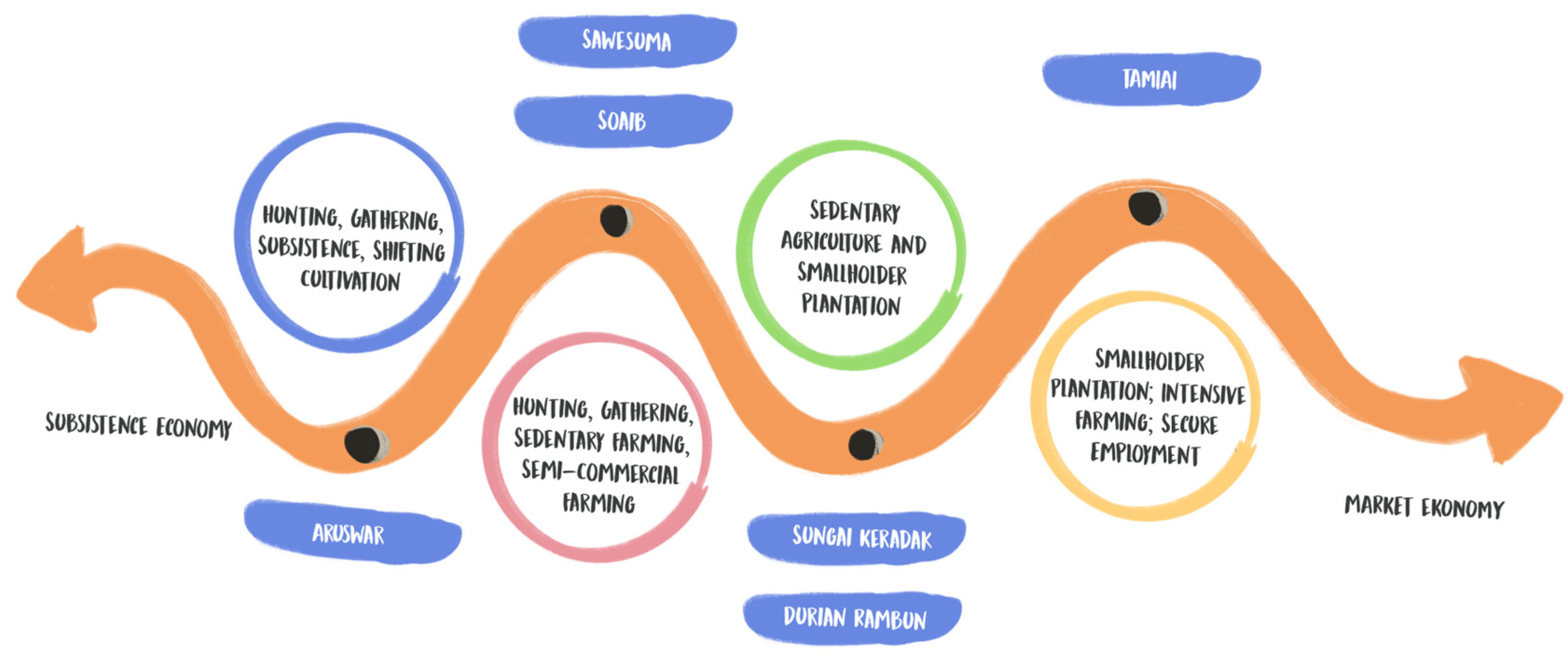

This paper therefore aims to make the case for an intersection between conservation, livelihood, and agrifood systems through the framing of diverse economies approach. We seek to foreground the different agrifood practices that forest-dependent communities in our case studies have enacted to build their livelihood and contribute to conservation, while demonstrating that this diversity of livelihoods, and even economic paradigms, can work in parallel, so long as they present within the space of possibility for the marginalized, forest-dependent communities to choose from. In the following sections, we begin by building a narrative (both in writing and visually) [

44] of diverse livelihoods within the communities in our six study sites in Jambi and Papua and end with the implications for how governments, academics, and NGOs should approach conservation issues in Indonesia and possibly elsewhere.

3. Results

3.1. Subsistence Livelihood Strategies

In our study, we have found that strong forest–people relationships manifest in how the village communities living around forests coexist and manage forest resources sustainably, albeit through different patterns of relationships, which we refer to as livelihood strategies. These livelihood strategies are built on the specific resources that they have; some are subsistence, some are connected to longer value chains, and some are shown in the form of alternative economies. In Papua, for example, natural resources such as coconut, areca nut (Areca cathecu), nibun (Oncosperma tigillarium), and sago (Metroxylon sagu) are an integral part of the community. Through these species, a variety of food and handicrafts are produced. People in Jambi, on the other hand, depend on smallholder plantations with industrial crops such as rubber (Hevea brasiliensis), coffee (Coffea canephora), and cinnamon (Cinnamomum burmannii). Some also nurture honeybees and grow rice, vegetables, kepayang (Pangium edule), and sugar palm (Arenga pinnata). Their livelihoods that are in direct contact with forests require a good balance between conservation and livelihoods.

In the three villages in Papua, the majority of households rely on subsistence farming as their main source of livelihood. They practice shifting cultivation with an average cultivated land area of about 250 m

2 or less. The locals themselves do not recognize the concept of metrics, so asking “how large is your farmland?” seems confusing. The activity of opening and working on a new patch of land usually involves all members of one or more families who have access to a particular hamlet or forest area. They apply a mixed garden system (

Figure 3), which is planting various types of plants in one area. Annual crops can be harvested in a matter of months, while perennial crops require a multi-year period on average. Traditional annual vegetables include the likes of waxy vegetables, gedi, mustard greens, local spinach, and others. In addition, people also grow tubers such as taro (

Alocasia sp.), yams (

Dioscorea sp.), cassava (

Manihot esculenta), and betatas (

Ipomoea batatas). Tree crops also vary, from the more traditional and native types such as coconut (

Cocos nucifera), matoa (

Pometia pinnata), breadfruit (

Artocarpus altilis), banana (

Musa spp.), areca nut, mango

(Mangifera indica), and bay tree to commercial and modern tree crops such as jackfruit (

Artocarpus heterophylla), guava (

Psidium guajava), coffee (

Coffea spp.), cocoa (

Theobroma cacao), durian (

Durio zibethinus), snake fruit (

Salacca edulis), and rambutan (

Nephelium lappaceum).

Gathering forest products is another livelihood strategy that is still practiced by people in the three villages in Papua. Wild plants that can be gathered are mainly plants used as traditional medicines such as itchy leaves, noken rope leaves, genemo leaves, and others. Gathering activities are usually carried out in the forest/hamlet belonging to the clan or to the wife’s relatives or the mother’s relatives. Of all the wild plants that are gathered and harvested, nothing is as important and essential as sago (

Metroxylon sago), the staple of people in the three villages and in Papua in general. The sago tree has many parts that can be utilized as food, including sago flour (the main product;

Figure 4), vegetables derived from the tops of sago tree leaves, sago mushrooms (sengkong) that grow on the remaining sago powder juice, and sago grubs from within the trunk (dobe yon). Sago harvesting is completed in groups, either in one large family of a single clan or together with other clans. If it is the latter, then there will be a fair distribution of sago products, which has been agreed upon by all clans involved. The process of gathering sago from one mature tree trunk can involve one or two adult women and lasts for several days, even weeks. Sago gathering takes a long time due to the interruption of other activities such as gardening, hunting, fishing, or gathering other forest products and the use of traditional tools.

In Jambi, farming is more commonly practiced and on a relatively larger scale, although one might still consider it as a smallholder activity. Small-scale shifting cultivation is still the dominant farming pattern in the three villages of Durian Rambun, Sungai Keradak, and Tamiai. Land owned by the village members is generally not certified, with their proof of land ownership being only in the form of unwritten knowledge passed between family members. Rivers, bunds, and certain plants such as areca nuts are usually used by the community as land boundary markers. Most of the smallholder plantations are located within the production forests that are managed by the Forest Management Units (FMUs) in each district. Legally, the community has obtained the right to manage the land for 35 years through a social forestry scheme with a permit area of 4484 ha each for Durian Rambun, 3241 ha for Sungai Keradak, and 850 ha for Tamiai.

Arable land is generally planted with various types of crops such as coffee, rubber, and cinnamon. In between these medium- and long-term crops, farmers usually grow patchouli, red ginger, and vegetables that can be harvested within a few months. Vegetables are planted by the community as a short-term strategy to meet daily needs before the coffee plant as a medium-term crop produces fruit. Rice is grown in all three villages in Jambi as an important staple food. In Durian Rambun, rice is grown on dry land (padi huma) in a more traditional way, whereas the practices transition in Sungai Keradak with rainfed paddy fields and in Tamiai with a more sophisticated irrigation system. Dryland rice is planted on different land each year through land clearing. This shifting practice is essential because farmers in Durian Rambun and Sungai Keradak do not use any chemical inputs and, thus, rely on soil nutrients provided by burning and land clearing. This practice is enough to provide each household with sufficient rice stock for the whole year. Growing rice in the three villages in Jambi acts not only as a household livelihood strategy but also as part of the collective work built by the community and passed down for generations.

Game and fish hunting are also important in both Papua and Jambi. In Papua, game hunting activities are carried out at certain times depending on the season and the need for animal protein (

Figure 5). These activities can be completed passively by installing tools made of wood and rope or through active hunting. During the rainy season, cassowaries (

Casuarius sp.), tree kangaroos (

Dendrolagus sp.), ground kangaroos (

Thylogale sp.), monitor lizards (

Varanus sp.), and others come out looking for food. During this period, hunting is completed collectively. The younger generation would do reconnaissance by following the game’s footprints to the hiding place, after which they would return to the village to inform the elders to carry out flanking and attacking while driving the animals out of their hiding places. After an animal is successfully shot and killed, the animal would be tied to a piece of wood and carried in turn to the home of the hunter or the customary leader to be split and distributed to all family members. However, each tribe in Papua owns a totem relationship with various types of animals and plants found in the region, which forbids them from consuming those animals and plants. If one violates this customary rule by mistakenly consuming or killing plants or animals that are their totems, they will traditionally be affected by illness, disease, death, or having no offspring. This is seen as a traditional way of wildlife conservation.

In Jambi, the river has a central social, cultural, and economic significance. In Durian Rambun and Sungai Keradak, people utilize rivers as a place to fish. From children to adults, people look for fish as a source of protein and for entertainment (

Figure 6). After school, children normally play and swim in the river whilst gathering fish with their harpoons and swimming goggles. The adults use fishing rods, harpoons, and nets. People in Sungai Keradak and Durian Rambun practice a semi-subsistence way of fishing, which means that they hunt primarily for their own consumption first and sell the excess to the village later. As a way to conserve fish and river resources in Jambi, the three villages impose a customary rule common in Sumatra, called lubuk larangan. This customary law designates a certain area of the river and riverbank as a prohibited zone, where people are forbidden to fish and make use of the area until a certain period of opening. The opening and closing of this hole usually involves customary, village, and religious officials as well as a thanksgiving ceremony in which community members eat and pray together on the site. In Durian Rambun, lubuk larangan is strengthened by both the customary and village laws, making it a binding code that implies social and administrative sanctions for those who break the rule.

3.2. Local Market Making in Papua and Jambi

After new roadways connected the three villages to cities and development ensued a few decades ago, some of the subsistence livelihood strategies have undergone significant changes and transformations. The market seems to be one of the adaptations. In Soaib, for instance, a Saturday market opens for a short period of time between 6 am and 7 am, which is visited by people from three villages around Soaib. This market sells produce from the local subsistence gardens. The proximity of Soaib to town has opened a new livelihood strategy, which is trading external consumer goods, from pillows to modern cakes. The local community has also established kiosks or small grocery stores that sell a variety of necessities, including phone credits. People in Soaib also sell garden produce to the modern market in Sentani. The products they sell include sago, areca nut, coconut, and various types of vegetables. Likewise, people in Aruswar also sell their garden produce to the Sarmi market (the Regency Capital), using what is known as a stacking system. For example, cassava and betatas are sold for 1.25 USD per pile, and bete and keladi for 2 USD per pile. Likewise, the access road connecting Sawesuma with Bongo, an immigrant area, has introduced market access to the community and changed the way they build their livelihood—from subsistence to market-oriented. In the three villages, the food they grow, gather, and hunt is used primarily for their own consumption, but the surpluses are then delivered to the local markets. Their profit can become quite lucrative; to illustrate, the prices of game meat are 1.5 USD per kg of pork and 3 USD for deer meat, where hunting experts can obtain up to 54 kg of game in one night of hunting.

A special note is given to people in Aruswar, who have for generations practiced a bartering tradition called Gon (

Figure 7). It is practiced every three months in a specific village close to the coast of Mamberamo, named Waim, 14 km from Aruswar. Gon is a barter tradition that brings together the Mamberamo people who are skilled in fishing with the Sarmi people, the majority of whom are farmers. They exchange the products of their respective professions, the Mamberamo people with fish, crab, and shellfish while the Sarmi people with their produce. In a barter system like Gon, market value is no longer relevant. A bowl full of seven individual crabs, each ranging from 15–17 cm in size, which in the modern market can be valued as high as 80 USD, are exchanged here with 1 kg of white sugar at a price of 2 USD. One might see

Gon as purely an economic activity (and one that is outdated), but it is in fact more than that. In Gon, people ask each other about familial ties and the extension of their clans, to the extent that it becomes a time for visitors to find distant relatives. This condition strengthens social cohesion. A barter economy such as Gon, in this case, plays a multifunctional role in the economy and livelihood of the local populations, particularly as a buffer for the imperfection of the cash economy, while maintaining the integrity of the local food system [

50], but also by building and strengthening social ties through acts of gift giving and reciprocity [

51]. In this sense, barter is not seen as a one-time transaction but as a continuous social and economic activity that maintains social ties and strengthens social capital.

3.3. Integrating with the Regional Value Chains

Livelihood strategies depend not only on the resources available locally and the social collective values practiced but also on the extent to which these communities and resources are connected to the broader market systems through both infrastructure and connectivity [

52]. Roads that connect villages in Papua with the nearest city or immigration area provide market access to people living in the village. Likewise, in Jambi, villages that are closest to the main road access, namely the provincial road, provide opportunities for people to acquire more diverse and competitive market access. This connectivity provides opportunities for communities to diversify their sources of livelihood; although it is a double-edged sword, as it can also increase the exploitation of the natural resources that leads to ecological degradation.

The key, we argue, is a more equal flow of goods, capital, and information between the villages and the wider networks. Proximity to markets does provide better access to better information [

53], such as how people in Soaib have utilized machine-based technology to process sago, a more complex sawmill and logging system to process timber, as well as easier access to the cattle market for their new form of savings. Better access to information means a better price for their products. However, it also means a community can gain more knowledge and skills from this flow of information. When comparing Soaib and the other two villages in Papua, knowledge of those in Soaib around sago processing is apparently better. Here, we look at a few examples of commodity-centered value chain economies in Papua and Jambi.

3.3.1. Cocoa in Soaib, Papua

The village of Soaib has a fairly large smallholder cocoa plantation of 68 hectares, owned by 68 people who are incorporated in a farmers’ group named Srukumani, with each member managing on average a hectare of land. This cocoa plantation has also been supported by the Jayapura Regency Government program since 2006. Cocoa smallholder plantations in Jayapura Regency, however, stretch way back to the era when the Dutch entered Papua in the early 1900s, during which several areas in Jayapura Regency were converted into cocoa plantations, one of which is the cocoa plantation in Soaib. Since 2012, cocoa bean fermentation technology was introduced to increase the value of cocoa. In that year, cocoa farmers in Soaib had successfully built their own supply chain for their cocoa. Srukumani’s cocoa beans were once exported to the Netherlands and Switzerland. Currently, however, cocoa plantations in Soaib are damaged by cocoa pod borers (

Conopomorpha cramerella) (

Figure 8), which the locals suspected to be caused by the government introducing a new variety of cocoa, of which pest infestation destroyed the whole plantation altogether. What is now remaining is not enough to make ends meet for the locals, and this left some of the farmers overwhelmed with the situation, and they chose to abandon their plantations altogether. There is currently no action taken to mitigate the situation.

3.3.2. Coconut in Aruswar, Papua

Coastal ecosystems dominated by coconut trees in Aruswar have huge potential for market development. As with other coconut-producing regions in Indonesia, coconut in Aruswar has always been integrated into the copra value chain. People in Aruswar sell copra only to one particular middleman, who keeps the downstream end of the value chain hidden from the community. This creates a dependency of the coconut producers on the middleman. Thus, in order to capture more added value across the value chain, the Aruswar community, especially the women’s group, was able to process coconut into virgin coconut oil (VCO;

Figure 9). This aligns with Papua Home Industry Coconut Oil (PHICO), one of the flagship programs of the Sarmi Regency Government supported through funds sourced from the APBD and APBN, which aimed to empower the community. The PHICO program operated a processing factory close to Aruswar, which, in addition to their own, also purchased VCO made by the Aruswar community for further manufacturing. Semi-finished VCO from Aruswar was purchased at 0.8 USD/liter by the PHICO company in Sarmi. One liter of VCO can be produced from about 10 coconuts, whereas in one week the women’s group can produce up to 20 L of VCO, which means that the revenue from VCO itself can reach up to 18 USD per week per household.

3.3.3. Rubber in Jambi

In Jambi, rubber was the main source of income for many households in Jambi, at least until 2014. Rubber began to be planted on a large scale in Jambi between 1924 and 1925 during the Dutch East Indies Government [

54], and in 1937–1940, rubber production was abundant and eventually prompted the Dutch government to impose restrictions by developing a coupon system, whereby farmers were only allowed to sell rubber if they had a rubber harvest permit coupon issued by the Dutch, and it was also during this time that, according to our informants in Sungai Keradak, rubber began to be planted in their village, around the 1940s. Durian Rambun was a late starter, with rubber only starting to be planted in the 2000s. In Jambi, rubber became a driving factor in the shift from a subsistence to a market-based economy. The introduction of rubber plants also changed the community’s farming system, shifting cultivation to a more sedentary agriculture [

55]. In 2004, the price of rubber soared to 1.2 USD/kg, which attracted many in Durian Rambun to grow rubber. Since then, and over the next 10 years, rubber became the main commodity cultivated by the community. Around 2014, however, the price of rubber fell to as low as 13 cents/kg, leading a lot of farmers to leave the crop behind. Most of the rubber trees were cut down and replaced with coffee and cinnamon, and those that were left undisturbed were entirely neglected. In Durian Rambun, some farmers now return to rubber (

Figure 10), making extra income from the sap that is sold to tauke, or middlemen, who would then sell to collectors in the Muara Siau sub-district market.

3.3.4. Coffee in Jambi

As an alternative to rubber, coffee is an important cash crop for many farmers in Jambi, including in the Durian Rambun, Sungai Keradak, and Tamiai villages. Robusta coffee began to be planted in Durian Rambun in 1997. The success of coffee farmers inspired people in Durian Rambun to grow coffee on their own. Meanwhile, in Sungai Keradak, coffee was only starting to be planted in 2018, although according to our informant, coffee is still not economically profitable for some. Coffee beans are generally sold to collectors in the village in the form of wet beans, dry beans, and green beans (

Figure 11). Farmers can sell their coffee harvest directly to the collectors without any processing after harvest, but the selling price of wet beans is usually lower. In Durian Rambun, coffee is sold in the form of green beans from farmers to village collectors (Tauke) at a price of 1.2–1.4 USD/kg, who will then sell to sub-district collectors at a price of 1.4–1.5 USD/kg. Meanwhile, in Tamiai, the village tauke sells coffee directly to large collectors in Padang and Lampung. It was only recently that the farmers’ groups in Durian Rambun and Tamiai began to process coffee beans to their final product of packaged coffee under the local brands Nilo Kopi and Kopi Bueh, respectively. This ground coffee was sold by the women’s group via shops or supermarkets in Bangko and Muara Siau, whereas Kopi Bueh are usually sold online and also deposited in the cooperative at the KPH Limau Office in Sungai Penuh.

3.3.5. Cinnamon in Jambi

Cinnamon is used as a long-term crop by the communities in the three villages and is usually harvested after more than six years of age (

Figure 12). Cinnamon began to be planted in Durian Rambun around the 1980s, while farmers in Sungai Keradak had only begun planting cinnamon in 1993 when the international price of cinnamon began to rise. Unfortunately, the pattern in cinnamon is rather similar to other industrial crops. During the 2000s, cinnamon prices started to drop, after which the farmers ceased to take care of the plant. Many cinnamon plantations in Tamiai were abandoned, and people migrated to Malaysia to find employment. The price of cinnamon improved from 2010 up until now, which explains why people treat cinnamon mostly as savings as opposed to main crops like coffee and rubber. Rather than having a regular yield, cinnamon is usually harvested only when the owner is in urgent need of a large amount of money, such as for education and health. This is also supported by the fact that the older the cinnamon tree, the greater the yield. Cinnamon sold to collectors is divided into several categories based on the amount of skin, water, and oil content. After being in the hands of collectors, the sweet peels will then be sorted again by collectors to be dried again and sold to large collectors or companies in Padang.

3.4. Opening Spaces for Alternative Economies?

In addition to the existing subsistence economy practiced by the majority of households in the six villages and the emerging value chain economy that grew along with the penetrating economic development, forms of alternative economies are also practiced across the communities. Here, we refer to Healy [

34], among others, who defines alternative economies as “processes of production, exchange, labor/compensation, finance, and consumption that are intentionally different from mainstream (capitalist) economic activity” (p. 338). The communities perform alternative economies by building linkages with conservation NGOs, local neighboring communities, and small groups of consumers. This activity breaks the boundaries of conventional economic systems that rely on value chains and regional markets but is also novel and unique so as to be separated from the traditional subsistence economic system.

In Sawesuma, for instance, the Digan clan designs an ecotourism plan in the form of bird-watching activities (

Figure 13). This is completed within the Digan customary forest, wherein at least eight species of birds of paradise live that have been identified and their positions pinpointed. Some of the tour guides were once illegal bird hunters, who changed course after a realization of the importance of conservation. Also, in Sawesuma, women make

noken (a bag made out of roots) and other handicrafts from the available local plants in the area, including nibung (

Oncosperma tigillarium), nipa (

Nypa fruticans), sago (

Metroxylon sagu), and tali sang (

Merremia peltata). The Nomblong Grime Paay Cooperatives, a local cooperative in Papua, also develops orchid cultivation, which is mainly run by youths. Orchids and their growth media are often taken from nearby forests. Although not many people are interested in this initiative, the presence of an alternative economy like this provides ways for people to maneuver between sources of income. In Jambi, a farmers’ group in Tamiai rear honeybees for their natural honey (

Figure 14). Collecting honey has a two-fold advantage. First, honey is a definite source of income. Second, honeybees help in pollinating perennial crops such as coffee. In Sungai Keradak, the younger generation of the rural community opened a river-based tourism, with activities including rafting and hiking.

In both Jambi and Papua, social cohesion still manifests in a voluntary collective work called gotong royong, a nationally recognized feature of rural communities to work collectively and provide mutual assistance without pay [

56]. This can come in the form of constructing the house of a community member who needs help (

Figure 15), cooking collectively during a neighbor’s wedding event, cleaning up rivers in a thanksgiving ceremony, a rotary-system collective farm labor among the women farmers’ group, and pooling money for someone in need. To illustrate, we witnessed first-hand how the community in Aruswar came together to help their neighbor who did not have any strength or money to fix her broken house. Young people from across the road brought with them timber, plywood, building materials, and their energy to help build her house. In just a day, the house is all brand new. We also documented women cooking together on a large wok for a wedding ceremony of one of the community members, while the men did some of the heavy work such as constructing the wedding stage and preparing the firewood to cook. In Durian Rambun, arisan kebun, or a rotary system for farm work, is a voluntary type of work among women farmers where they take turns in working together to maintain a member’s plantation. Not only does this activity save money but it also strengthens the social bond among the women. We, therefore, argue that this alternative form of economy, in combination with ways in which the community groups in the six villages devised new approaches to their more conventional agricultural practices (such as machine processing of sago harvesting in Soaib and producing branded coffee in Sungai Keradak and Tamiai), demonstrated their versatility in building diverse economies that go beyond capitalistic agrifood systems.

4. Discussion

The stories of the six villages have illustrated that in their local social-ecological context, the communities are able to adapt to various changes due to their diverse forms of livelihood and economic means. In the cases of the commodity value chains, all share similar challenges: volatility of the international market prices, distance and road infrastructures, and conventional supply chains dominated by a limited number of middlemen (tauke). Similar cases have been documented elsewhere, in Indonesia and other developing countries [

31,

57,

58]. Due to the barrier of transport from their villages to farms, which often makes it more expensive than channeling their goods from the village to the regional market, smallholder plantations can become a disincentive for farmers to work on their land. For farmers and farm workers who have limited access to capital and technology, relying on a regional or global value chain can prove to be a challenge. However, capturing value downstream, by processing the commodities into branded products with premium prices, may not be the best solution, considering the fact that rural communities often have limited access to information and markets [

31].

In Jambi, history shows how people juggled their three main commodities (coffee, cinnamon, and rubber) in a way that enabled them to survive economic shocks. Rubber in Jambi was the first to be introduced, followed by cinnamon in the 1980s and coffee in 1997. However, in the 20 years since the introduction of cinnamon, the price of cinnamon fell hard, leaving people neglecting their farms. This was followed by an increase in the international price of rubber between 2004 and 2014, which pushed farmers to steer back to rubber. After 2014, rubber prices once again dropped, which was serendipitously followed by another increase in cinnamon prices. While other regions that relied solely on rubber became frustrated and shifted to the notorious oil palm, farmers in Durian Rambun, Tamiai, and Sungai Keradak could easily bounce back to cinnamon. This capacity to adapt through multiple cash crops built a versatility to adapt to economic shocks. Realizing the benefit of crop diversification, farmers now maintain a variety of plantation landscapes on their land, intensively managing one patch of land while keeping others ‘dormant’. From an agribusiness viewpoint, this is not necessarily efficient. However, through their idea of saving, this redundancy helps to provide a sense of economic security and resilience for these farmers [

59].

On a similar note, some of the more innovative farmers in Jambi and Papua came up with value-adding activities. Soaib experimented with cocoa fermentation, Aruswar processed coconut into VCO, Sungai Keradak made powdered cinnamon as a supplemental beverage, while Tamiai and Durian Rambun created a branded packaged coffee. Although the market has not been well established for these innovative products, and only time will tell whether this will ever expand, this endeavor of creating new ways of working with biological resources, a term now known as biological economy [

60], seems worth the shot. In addition, the form of alternative economies developed through ecotourism, orchidariums, and handicrafts may broaden the opportunity for non-capitalistic economic spaces [

34].

It is no surprise that the smallholder farmers in Jambi and Papua build a diversity of livelihoods that rely not only on land-based products but also on a spectrum of income sources, including off-farm income, remittance (from working as a migrant worker), and various forms of alternative economies. This is what Jeffrey Neilson identifies as fortress farming—an economy supported by cash crops as a financial buffer and savings, but upon which different livelihood strategies are then built [

33]. The implication of the intervention strategy is simple: rather than pushing these community groups to advance into the global value chains by providing high-quality cash crops, we might instead build as many economic and cultural spaces as possible.

Social cohesion is also proven to build into the strength of the six community groups. Non-capitalistic labor work, in its many forms, is a feature of rural communities across Indonesia [

56], and yet this becomes eroded as more and more capitalistic practices grab hold [

61]. The key is to provide a social space where one can still practice this form of collective action. In both Papua and Jambi, we have found that local economic spaces (market, farm, river) function not only as economic space per se but also as social spaces where people establish networks and build social capital.

In using the diverse economies framework, we, therefore, assert that what is important is not only a diversity of livelihoods (as many studies have shown; see [

62]) but also the versatility and adaptability of individuals and collectives to shift between one mode of livelihood (i.e., subsistence economy) and another (market/value-chain based economy) and another (alternative economy). In a situation in which the market economy is the only foundation of livelihood strategies, no matter how diverse they are, it would create a lock-in trap, which hinders the people’s capacity to adapt to crises and adversities. This is, fortunately, not the case in Jambi and Papua. Here, the way communities move flexibly from one economic mode (market economy) to another (subsistence), from global value chains to local food systems, is shown to reduce their vulnerability to external crises and shocks (

Figure 16). This diversity of livelihood has implications for the diversity of agrifood systems, one in which global value chains dovetail and intertwine with local food systems and where the distinctions between subsistence, capitalistic, and alternative economies are no longer visible.

Studies have shown that what connects nature conservation, livelihood, and agrifood systems is the return to agroecology and local food systems (see, e.g., [

63,

64]). We argue differently, or perhaps, more inclusively. Using a diverse economic-liberation environmentality framework, we shift our attention from romanticizing traditionality and environmentally friendly approaches as solutions to a conservation–livelihood nexus and to acknowledging how local communities take the lead in mobilizing their resources for their own well-being through a diverse range of livelihood strategies. What comes out of this self-mobilizing role is a conservation practice that goes beyond technicality, to borrow Li’s term [

20]. The communities’ dependence on forest ecosystems, through their diverse economies, does not devour nature but instead creates interdependent relationships. In terms of community-based conservation, the community’s sense of dependence on, and belonging to, their local resources builds into their willingness to protect their forests from external pressures. The phrase “hutan itu mama”, or the forest is our mother, which was mentioned repeatedly in our interviews, showed the significance of forest conservation within the lives of the communities as well as the ethics of care that founded this relationship.

5. Conclusions

This paper has made the case for an intersection between conservation, livelihood, and agrifood systems through a diverse economic-liberation environmentality approach. Our argument, which was substantiated by the narratives provided in the Results section and later emphasized in the Discussion, is that a diverse economies approach goes beyond merely acknowledging crop, landscape, or livelihood diversifications. It is a viewpoint and political project that attempts to move beyond the dichotomy of capitalistic and alternative economies. Through a diverse economies approach, we have seen that the local communities work seamlessly through intertwining between global and local food systems. The way in which the communities mobilize their resources builds a stronger appreciation for their forests, which eventually drives conservation practices. It was not necessarily the technicalities that made a case for conservation but their ethics, and politics, of care. The different agrifood practices that forest-dependent communities have enacted to build their livelihood and contribute to conservation demonstrate that this diversity of livelihoods, and even economic paradigms, can work in parallel, so long as they are present within the space of possibility for the marginalized, forest-dependent communities to choose from.

Our message, however, should be clear: a versatile community does not mean that the state is free of its responsibility. On the contrary, true to the diverse economies framework, the government should provide as much space as possible for these communities to build a balanced and healthy relationship with their ecologies. The politics of care [

35,

40,

43] means that we should listen more to what the local people need and believe in their ability to care for the forest. This includes revisiting some of the indicators used to measure the success and failure of forest conservation. So, instead of focusing on the hectares of social forestry created and the number of households involved, we can see better through indices such as diversity of income, quality of life, access equality, social capital, and trust.

There are at least three recommendations that we can offer to the government, NGOs, and development agencies on ways to strengthen community-based conservation practices and sustainable agrifood systems. First, we should aim to build as many spaces as possible for alternative economies to flourish and enable the flexibility and adaptability of the local communities to maneuver across those spaces. Second, we should help to strengthen how the community manages its assets and savings and see beyond a short-term economic rationale. We should see that the commodity value chain is only one part of the community’s livelihood strategies, and we need to identify and acknowledge the other strategies, including subsistence and sharing economies. Third, the government should particularly play a stronger role in the provisioning of public infrastructure, but one that aligns with the community’s own natural and socio-cultural capital. So, instead of building central markets, the government could distribute smaller local markets closer to the communities.

There is, however, a blind spot that we missed and we believe to be a central point in building a diverse economy: the role of women in the social, economic, and cultural everyday lives of the community. In many key community activities—gon, local market, arisan kebun, healthcare, education, and even among the alternative economies, women have been pivotal. We would like to suggest future research to see, acknowledge, and strengthen the role of women in building a balance between sustainable agrifood systems and community-based conservation practices.