Factors Determining the Choice of Pro-Ecological Products among Generation Z

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The education of the surveyed representatives of Generation Z influences their choices of environmentally friendly products;

- The environmental (pro-ecological) approach of the respondents of Generation Z is associated with their knowledge and experiences, as well as brand and image perceptions.

3. Results

- Product features and specifications: description of the physical attributes, features, and technical specifications of the product;

- Durability and reliability: assessment of how long the product is expected to last and how well it functions over time. A reliable product is often associated with higher quality;

- Performance: information on how well the product performs its intended function. High-performance products are typically perceived as higher in quality;

- Materials and ingredients: detail the materials or ingredients used in the product’s production. High-quality, sustainable, or natural ingredients can enhance the perceived quality;

- Craftsmanship and workmanship: highlight the skill level and attention to detail in the product’s manufacturing. Fine craftsmanship often leads to higher perceived quality;

- Brand reputation: analyze the reputation of the brand or manufacturer. Established and trusted brands may automatically convey higher product quality;

- Price: consider the price point and its relation to the market. Consumers often associate higher prices with better quality, although this is not always the case;

- Warranty and customer support: evaluate the warranty and customer support provided by the manufacturer. A strong warranty and reliable customer service contribute to perceived quality;

- Design and packaging: discuss the design and packaging of the product. Attractive and well-thought-out design can positively impact perceived quality;

- Market context: examine the product’s context within the market. How does it compare to similar products from competitors? This context can shape consumer perceptions;

- User experience: consider the overall experience of using the product. Factors like ease of use, convenience, and functionality play a role in perceived quality;

- Consumer expectations: recognize that consumer expectations and past experiences influence how a product’s quality is perceived. Meeting or exceeding these expectations is crucial;

- Cultural and regional variations: be aware of cultural and regional differences in quality perception. What is perceived as high quality in one region may differ elsewhere according to cross-cultural differences in consumer behavior [54].

- Environmental and ethical considerations: today, many consumers value products that align with environmental and ethical principles. Highlight any eco-friendly or ethical aspects of the product [55].

4. Discussion

- Product innovation: investing in research and development to create innovative, sustainable products that meet or exceed consumer expectations in terms of quality, performance, and price. This can involve using eco-friendly materials, reducing energy consumption, or implementing green manufacturing processes [61];

- Marketing and branding: developing effective marketing campaigns that emphasize the eco-friendly features and advantages of the products. Focus on building a good brand image that aligns with sustainability values to attract environmentally conscious consumers. At this point, the impact of another factor, which is the fashion for ecological behavior, is revealed. This problem is pointed out, among others, by A. Brisman. The author points out that some organic products are purchased by consumers in order to demonstrate a certain attitude and also because of the prevailing fashion for such behavior. As an example, he analyzes the reasons for the purchase of hybrid cars by Americans [62].

- Partnerships and collaborations: collaborating with relevant stakeholders such as environmental organizations, government agencies, and industry associations to promote sustainable practices and gain support for eco-friendly products. Joint initiatives can increase visibility and credibility [63];

- Accessibility and availability: ensuring that environmentally friendly products are readily available and easily accessible to consumers. This includes expanding distribution channels, partnering with retailers, addressing, transporting, and other logistical challenges. Distribution channels and supply chains should also be geared towards pro-ecological activities.

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. An Eco-Waking Measuring Global Awareness, Engagement and Action for Nature; The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://f.hubspotusercontent20.net/hubfs/4783129/An%20EcoWakening_Measuring%20awareness,%20engagement%20and%20action%20for%20nature_FINAL_MAY%202021%20(1).pdf?__hstc=130722960.ecb206528da823f5ba86141aa6e8eac6.1642377481532.1642377481532.1642377481532.1&__hssc=130722960.1.1642377481533&__hsfp=2719519617&hsCtaTracking=96a022a5-8be1-44ee-82fc-ced6164b8590%7C0c8892b7-4e13-464f-9b50-75e692c189ef (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Kamińska-Witkowska, A.; Matuszak-Flejszman, A. Possibility of using EMAS environmental reporting requirements for ESG reporting in selected automotive corporations. Econ. Environ. 2023, 85, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piórkowska, K.; Witek-Crabb, A.; Lichtarski, J.; Wilczyński, M.; Wrona, S. Strategic thinkers and their characteristics: Toward a multimethod typology development. Int. J. Manag. Econ. 2021, 57, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomska, J.; Szpulak, A.; Wołczek, P. A multi-item scale for open strategy measurement. Decision 2023, 50, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołoducho-Pelc, L.; Sulich, A. Natural Environment Protection Strategies and Green Management Style: Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methorst, J.; Rehdanz, K.; Mueller, T.; Hansjürgens, B.; Bonn, A.; Böhning-Gaese, K. The importance of species diversity for human well-being in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 181, 106917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam-Sing Wong, S. The influence of green product competitiveness on the success of green product innovation: Empirical evidence from the Chinese electrical and electronics industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mustafa, S. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Bełch, P.; Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M.; Pacana, A.; Bednarova, L. Determinants of making decisions in improving the quality of products. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol.-Organ. Manag. Ser. 2022, 157, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-W. Enhancing Green Absorptive Capacity, Green Dynamic Capacities and Green Service Innovation to Improve Firm Performance: An Analysis of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Sustainability 2015, 7, 15674–15692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huo, J.; Zou, H. Green process innovation, green product innovation, and corporate financial performance: A content analysis method. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fura, B. The Role of Financial Situation in the Relationship between Environmental Initiatives and Competitive Priorities of Production Companies in Poland. Risks 2022, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Gavurova, B.; Oláh, J. Financial risk, renewable energy technology budgets, and environmental sustainability: Is going green possible? Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 909190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sawyer, L.; Safi, A. Institutional Pressure and Green Product Success: The Role of Green Transformational Leadership, Green Innovation and Green Brand Image. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 704855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Shu, C.; Wei, J.; Gao, S. Green management, firm innovations, and environmental turbulence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 28, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacana, A.; Czerwińska, K. Indicator analysis of the technological position of a manufacturing company. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2023, 29, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, R.E. The Truth about Making Smart Decisions; Pearson Education Inc., FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Małkowska, J.; Grela, E.; Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M. Tygiel kulturowy a zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem produktu. Probl. Jakości 2022, 54, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, J.; Botti, M.; Thomas, S. Do knowledge and experience have specific roles in triage decision-making? Acad. Emerg. Med. 2007, 14, 722–726. [Google Scholar]

- Bełch, P. Management of a transport company during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol.-Organ. Manag. Mod. Ind. Sci. 2021, 150, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K.E.; West, R.F. On the relative independence of thinking biases and cognitive ability. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 672–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruine de Bruin, W.; Parker, A.M.; Fischhoff, B. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, M.; Krueger, J.I. Two Egocentric Sources of the Decision to Vote: The Voter’s Illusion and the Belief in Personal Relevance. Political Psychol. 2004, 25, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüllermeier, E. Experience-Based Decision Making and Learning from Examples. In Operations Research Proceedings; Chamoni, P., Leisten, R., Martin, A., Minnemann, J., Stadtler, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingebiel, R.; Zhu, F. Sample decisions with description and experience. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2022, 17, 1146–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M. Pułapki decyzyjne a system zarządzania środowiskowego. In Rachunkowość na Rzecz Zrównoważonego Rozwoju; Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, nr 436; Dziawgo, D., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2016; pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M.; Bełch, P.; Siwiec, D.; Bednarova, L.; Pacana, A. The use of instruments aimed at improving the quality of products (research results). Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol.-Organ. Manag. Ser. 2022, 157, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belas, J.; Gavurova, B.; Schonfeld, J.; Zvarikova, K.; Kacerauskas, T. Social and Economic Factors Affecting the Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2007, 16, 220–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska-Mihułowicz, M.; Chudy-Laskowska, K. Factors influencing investors’ decision making in Polish companies—On example of RFID systems. In Hradec Economic Days 2019; Double-blind peer-reviewed proceedings part I. of the international scientific conference; Jedlička, P., Marešová, P., Soukal, I., Eds.; University of Hradec Králové: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2019; Volume 9, pp. 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Marc, I.; Kušar, J.; Berlec, T. Decision-Making Techniques of the Consumer Behaviour Optimisation of the Product Own Price. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacana, A.; Siwiec, D. Model to Predict Quality of Photovoltaic Panels Considering Customers’ Expectations. Energies 2022, 15, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Garg, A.; Ram, S.; Gajpal, Y.; Zheng, C. Research Trends in Green Product for Environment: A Bibliometric Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, A.; Seock, Y.-K.; Shin, J. Exploring the perceptions and motivations of Gen Z and Millennials toward sustainable clothing. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 51, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confetto, M.G.; Covucci, C.; Addeo, F.; Normando, M. Sustainability advocacy antecedents: How social media content influences sustainable behaviours among Generation Z. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 758–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolot, A. The characteristic of Generation Z. e-Mentor 2018, 2, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auliandri, T.A.; Thoyib, A.; Rohman, F.; Rofiq, A. Does green packaging matter as a business strategy? Exploring young consumers’ consumption in an emerging market. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Cruceru, A.F.; Balaceanu, C.T.; Chivu, R.-G. Consumers’ behavior concerning sustainable packaging: An exploratory study on Romanian consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; Hoefel, F. ‘True Gen’: Generation Z and Its Implications for Companies, FG Trade/Getty Images, McKinsey&Company. November 2018, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/consumer%20packaged%20goods/our%20insights/true%20gen%20generation%20z%20and%20its%20implications%20for%20companies/generation-z-and-its-implication-for-companies.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Dabija, D.-C.; Brândușa, M.B.; Pușcaș, C. A Qualitative Approach to the Sustainable Orientation of Generation Z in Retail: The Case of Romania. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PrakashYadav, G.; Rai, J. The Generation Z and their Social Media Usage: A Review and a Research Outline. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 9, 110–116. Available online: https://www.gjeis.com/index.php/GJEIS/article/view/222 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Parzonko, A.J.; Balińska, A.; Sieczko, A. Pro-Environmental Behaviors of Generation Z in the Context of the Concept of Homo Socio-Oeconomicus. Energies 2021, 14, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhghenti, T.; Gedenidze, G. Sharing economy platforms in Georgia: Digital trust, loyalty and satisfaction. Mark. Menedžment Innovacij 2022, 2, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Pino, M.C.; D’Amico, S. Exploring the Psychosocial Antecedents of Sustainable Behaviors through the Lens of the Positive Youth Development Approach: A Pioneer Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, W. Ekologia Wyrobów; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bryła, P. Znaczenie marki na rynku ekologicznych produktów żywnościowych. In Strategie Budowania Marki i Rozwoju Handlu. Nowe Trendy i Wyzwania dla Marketingu; Domański, T., Ed.; Uniwersytet Łódzki–Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne S.A.: Łódź, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek-Łopacińska, K.; Sobocińska, M.; Krupowicz, J. Purchase Motives and Factors Shaping Consumer Behaviour on the Ecological Product Market (Poland Case Study). Sustainability 2022, 14, 15274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowastowski, J. Przemysł elektrotechniczny w Polsce. MM Mag. Przemysłowy 2012, 4, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A.; Simková, Z.; Metszősy, G.; Vozňáková, I. Current activities for quality and natural environment taken by selected enterprises belonging to SMEs from the electromechanical industry. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol.-Organ. Manag. Ser. 2023, 172, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B.; Dirani, K.M. Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 46, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Jones, C.; Frazier, R. Engineering Education for Generation Z. Am. J. Eng. Educ. (AJEE) 2017, 8, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, J.; Karwot, J. Pro-Ecological Behavior: Empirical Analysis on the Example of Polish Consumers. Energies 2022, 15, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balińska, A.; Jaska, E.; Werenowska, A. The role of eco-apps in encouraging pro-environmental behavior of young people studying in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balińska, A. Analysis of Consumer Pro-Environmental Behavior—The Context of Scientific Research. Energies 2022, 15, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galina, T.; Urkmez, T.; Ralf, W. Międzykulturowe różnice w zachowaniach konsumentów: Przegląd literatury studiów międzynarodowych. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 13, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaikauskaite, L.; Butler, G.; Helmi, N.F.S.; Robinson, C.L.; Treglown, L.; Tsivrikos, D.; Devlin, J.T. Hunt–Vitell’s General Theory of Marketing Ethics Predicts “Attitude-Behaviour” Gap in Pro-environmental Domain. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 732661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, G.K. 100 Statistical Tests, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK; Thousands Oaks, CA, USA; New Dheli, India, 2006; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Kennard, D.K.; Gould, K.; Putz, F.E.; Fredericksen, T.S.; Morales, F. Effect of disturbance intensity on regeneration mechanisms in a tropical dry forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 162, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aczel, A.D.; Sounderpandian, J. Statystyka w Zarządzaniu; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seemiller, C.; Grace, M. Generation Z: Educating and Engaging the Next Generation of Students. About Campus 2017, 22, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatto, B.; Erwin, K. Teaching Millennials and Generation Z: Bridging the Generational Divide. Creat. Nurs. 2017, 23, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, I.; Agarski, B.; Ilić Mićunović, M. Environmental product declarations based on life cycle assessment. In Innovations in Circular Economy—Environmental Labels and Declarations; Ziółkowski, B., Agarski, B., Šebo, J., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Rzeszowskiej: Rzeszów, Poland, 2021; pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Brisman, A. It takes green to be green: Environmental elitism, „ritual displays” and conspicuous non-consumption. Dak. North Dak. Law Rev. 2009, 85, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, U.; Mazzola, E.; Mohan, U.; Bruccoleri, M.; Awasthi, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. How selection of collaborating partners impact on the green performance of global businesses? An empirical study of green sustainability. Prod. Plan. Control. 2020, 32, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyńska, A. Willingness to pay for green products vs. ecological value system. Int. J. Synerg. Res. 2014, 3, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Jusuf, E.; Gunardi, A. Green sustainability: Factors fostering and behavioural difference between Millennial and Gen Z: Mediating role of green purchase intention. Econ. Environ. 2021, 76, 31. Available online: https://www.ekonomiaisrodowisko.pl/journal/article/view/357 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Witek, L. Zachowania konsumentów na rynku produktów ekologicznych w Polsce i innych krajach Unii Europejskiej. Handel Wewnętrzny 2015, 1, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Witek, L. Barriers to Green Products Purchase—From Polish Consumer Perspective. In Proceedings of the Innovation Management, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability (IMES 2017), University of Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 25–26 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jerzyk, E. Sustainable packaging as a determinant of the process of making purchase decisions from the perspective of Polish and French young consumers. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2015, 3, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentel, U.; Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M. Does standardization have an impact on innovation activity in different countries? Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hora, S.T.; Bungau, C.; Negru, P.A.; Radu, A.-F. Implementing Circular Economy Elements in the Textile Industry: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Siwar, C.; Chamhuri, N.; Sarah, F.H. Integrating General Environmental Knowledge and Eco-Label Knowledge in Understanding Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jităreanu, A.F.; Mihăilă, M.; Alecu, C.-I.; Robu, A.-D.; Ignat, G.; Costuleanu, C.L. The Relationship between Environmental Factors, Satisfaction with Life, and Ecological Education: An Impact Analysis from a Sustainability Pillars Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polska Akademia Nauk. Available online: https://pan.pl/blog/diagnoza-polakow-wedlug-europejskiego-sondazu-spolecznego/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Eastman, J.K.; Iyer, R. Understanding the ecologically conscious behaviors of status motivated millennials. J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali-Zinoubi, Z. Examining Drivers of Environmentally Conscious Consumer Behavior: Theory of Planned Behavior Extended with Cultural Factors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Hardisty, D.J.; Habib, R. The Elusive Green Consumer, Harvard Business Review. July–August 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/archive-toc/BR1904/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareie, B.; Navimipour, N.J. The impact of electronic environmental knowledge on the environmental behaviors of people. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoveva, G.; Samukti, D.R. Green marketing: Strengthen the brand image and increase the consumers’ purchase decision. MIX J. Ilm. Manaj. 2021, 10, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Khaskheli, A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A. Factors influencing green purchase behavior among millennials: The moderating role of religious values. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 1417–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, M. Green Product Supply Chain Coordination Under Demand Uncertainty. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 25877–25891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.U.; Aslam, S.; Murtaza, S.A.; Attila, S.; Molnár, E. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Green Purchase Intentions: Mediating Role of Green Brand Image and Consumer Beliefs towards the Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Varga, K.; Pacana, A. Qualitative-Environmental Actions Expected by SMEs from V4 Countries to Improve Products. Syst. Saf. Hum.-Tech. Facil.-Environ. 2023, 5, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Eco-consciousness | They show a unique sensitivity to ecological issues, which sets them apart from previous generations. This trend means that these products and brands gain favor, which promotes consistently sustainable production, responsible consumption, circular economy, and corporate social responsibility, i.e., a proactive and eco-innovative approach to environmental protection. |

| Digital presence | Highly competent in the area of technology: Generation Z (referred to as the digital elite) is connected closely to the internet and social media platforms. It is where they look for information on the parameters of the products they are interested in, guided by reviews, opinions, and online content when making purchasing decisions. The expression of their dissatisfaction can easily be spread by consumer ostracism. |

| Social values | Their interest in social issues is evident in their approach to shopping. They prefer brands that explicitly support values such as equality, inclusion, and social justice. |

| Authenticity | For Generation Z, the authenticity and honesty of companies are crucial. They expect transparency in communications and actions. |

| Shopping experience | Interactive and engaging shopping experiences, both online and in store, are of high value to Generation Z. Companies that offer unique and engaging interactions attract their attention. Young people are looking for thrills and experiences. |

| Peer influence | Recommendations and suggestions from peers play a significant role in the purchasing decisions of this group. This generation is more likely to trust the recommendations of their friends. On the other hand, autonomy and independence are of high importance to them. They want to make their own decisions and express their identity in this way. |

| Diversity and inclusion | Brands are expected to be more representative and diverse, reflecting the diversity of society. Companies that promote inclusion and diversity win their favor. |

| Mobility | Smartphones are an integral part of Generation Z’s life, making online shopping and mobile app usage a crucial part of their purchasing process. It is significant to be aware that Generation Z has had access to a vast amount of information and communication opportunities since childhood, which has shaped their thinking and behavior in a specific way. |

| Features | %(N) | Features | %(N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Marital status | ||

| Poland | 52% (415) | single | 64% (508) |

| Czech Republic | 17% (138) | married | 6% (46) |

| Hungary | 17% (133) | partner relationship | 28% (229) |

| Slovakia | 14% (110) | widow/divorced | 2% (13) |

| Gender | Education | ||

| male | 36% (285) | elementary | 17% (134) |

| female | 61% (489) | medium | 50% (397) |

| I do not want to answer | 3% (22) | higher | 33% (265) |

| Place of living | Number of people in the household | ||

| rural area (e.g., village) | 35% (278) | one two three or four over 4 | 3% (23) 12% (98) 26% (203) 59% (472) |

| city up to 20,000 inhabitants | 11% (86) | ||

| a city of 20,000 to 150,000 inhabitants | 14% (111) | ||

| a city with more than 150,000 to 500,000 inhabitants | 36% (288) | ||

| a city with more than 500,000 inhabitants | 4% (33) | ||

| Factors | Communalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Knowledge and Experience | Brand and Image | ||

| Legal and other requirements | 0.6322 | 0.3153 | 0.2241 | 0.5493 |

| Product packaging | 0.7129 | 0.0559 | 0.3668 | 0.6459 |

| Eco-label | 0.8384 | 0.0760 | 0.2321 | 0.7626 |

| Environmental impacts of the product | 0.8327 | 0.1784 | 0.1913 | 0.7618 |

| Opinion of other customers (e.g., reviews) | 0.0755 | 0.7164 | 0.3103 | 0.6152 |

| Individual customer needs | 0.1004 | 0.7337 | 0.1852 | 0.5827 |

| Previous personal experience with the product | 0.1271 | 0.8117 | 0.1530 | 0.6984 |

| Product price | 0.1021 | 0.7355 | 0.3043 | 0.6440 |

| Expected product life (durability) | 0.3783 | 0.7224 | 0.0829 | 0.6718 |

| The image of the (manufacturing) company | 0.1439 | 0.3162 | 0.6927 | 0.6005 |

| Renown (prestige) of the product brand | 0.1621 | 0.2004 | 0.7537 | 0.6345 |

| The modernity of the product/design | 0.3123 | 0.2767 | 0.6648 | 0.6161 |

| Current practices and prevailing trends | 0.3629 | 0.1904 | 0.6929 | 0.6481 |

| Expert opinion | 0.4195 | 0.4346 | 0.2810 | 0.4438 |

| The period during which the product is on the market | 0.3747 | 0.1399 | 0.5793 | 0.4956 |

| Timely delivery | 0.3961 | 0.3621 | 0.4443 | 0.4854 |

| Payment method | 0.4383 | 0.3934 | 0.3858 | 0.4957 |

| Guarantee period | 0.5105 | 0.5567 | 0.2488 | 0.6324 |

| Variance | 3.69 | 3.97 | 3.32 | 10.98 |

| % Var. | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.18 | |

| b * | Std. Error (b *) | b | Std. Error (b) | t (603) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.741 | 0.134 | 5.544 | 0.0000 *** | ||

| Brand and image | 0.448 | 0.040 | 0.481 | 0.043 | 11.092 | 0.0000 *** |

| Knowledge and experience | 0.216 | 0.041 | 0.223 | 0.042 | 5.353 | 0.0000 *** |

| Environmental | Knowledge and Experience | Brand and Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.0000 *** | 0.0223 * | 0.0008 *** |

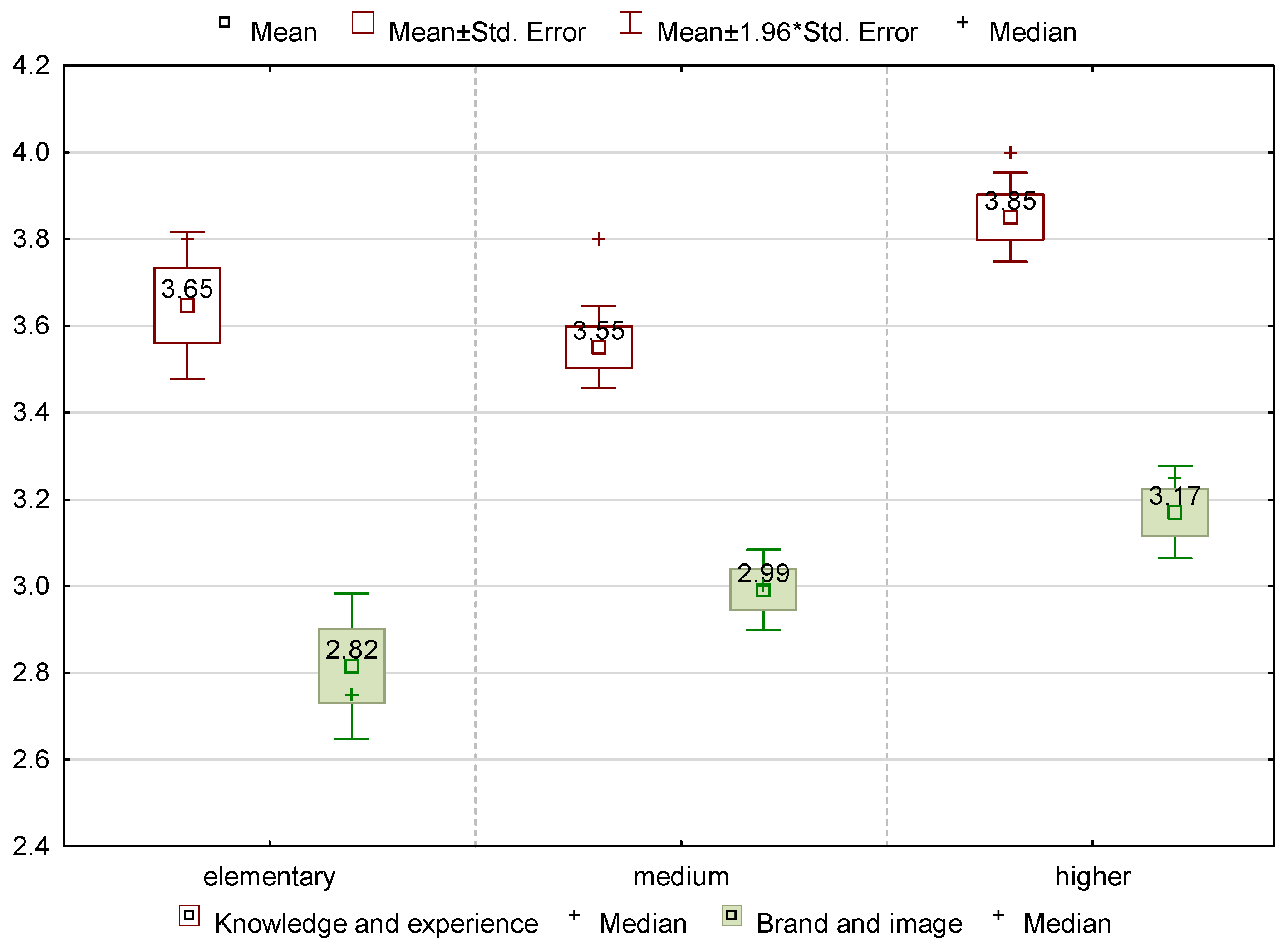

| Education | 0.7645 | 0.0007 *** | 0.0027 ** |

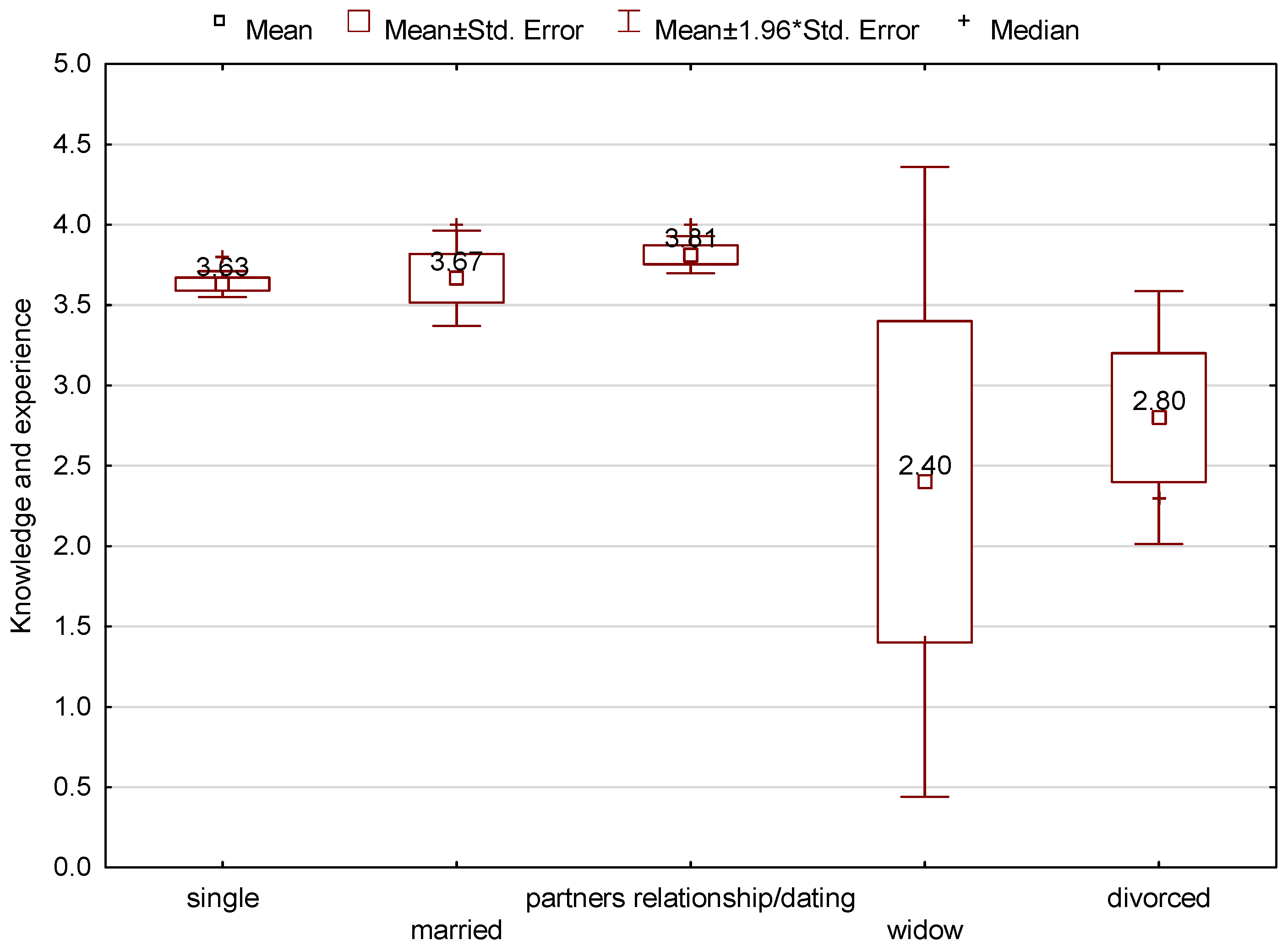

| Marital status | 0.4137 | 0.0121 * | 0.1121 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bełch, P.; Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M.; Chudy-Laskowska, K.; Vozňáková, I.; Gavurová, B. Factors Determining the Choice of Pro-Ecological Products among Generation Z. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041560

Bełch P, Hajduk-Stelmachowicz M, Chudy-Laskowska K, Vozňáková I, Gavurová B. Factors Determining the Choice of Pro-Ecological Products among Generation Z. Sustainability. 2024; 16(4):1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041560

Chicago/Turabian StyleBełch, Paulina, Marzena Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, Katarzyna Chudy-Laskowska, Iveta Vozňáková, and Beáta Gavurová. 2024. "Factors Determining the Choice of Pro-Ecological Products among Generation Z" Sustainability 16, no. 4: 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041560

APA StyleBełch, P., Hajduk-Stelmachowicz, M., Chudy-Laskowska, K., Vozňáková, I., & Gavurová, B. (2024). Factors Determining the Choice of Pro-Ecological Products among Generation Z. Sustainability, 16(4), 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041560