1. Introduction

Gender equality and women’s empowerment are key development goals that have been welcomed over the years. In the era of globalization, it has been identified and seen as important for sustainable development [

1] and has been a feature of development assistance since the 1990s [

2]. This was first highlighted at the 1995 United Nations International Conference on Women in Beijing [

3], where there was a call to reduce gender inequality and promote women’s empowerment. The need for this was reaffirmed following the establishment of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in New York in September 2015, with the publication of the goals on 21 October that year in a document entitled ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, which contained 17 goals and 169 targets.

This agenda was an action plan for people, the planet, and prosperity, and embedded in it was the need to realize human rights for all, achieve gender equality, and empower all women and girls, which was captured in SDG 5. One of the core goals and global priorities of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for the SDGs is to ‘leave no one behind’, an ambitious plan to achieve a sustainable future for all [

4]. These goals are all interlinked and encompass the global challenges we face every day, such as inequality, climate change, poverty, environmental degradation, reaching prosperity, establishing justice, ensuring inclusivity, and securing gender equality, which is at the heart of this work. In short, it is about addressing issues of ‘economic growth, social development and environmental protection’, because without them, it is impossible to address the issue of gender equality [

4]. Gender equality is one of the specific targets aimed at empowering all women and girls, with an emphasis on the need to have reliable measures in place to track progress on this issue, although some measures have already been proposed by the UNDP in 1994 after the Cairo conference, where they developed the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), which focuses on the three key variables that reflect women’s participation in society—political power or decision-making, education, and health [

5].

Women’s empowerment has been in the limelight of many international organizations over the past decades and has been given different definitions and meanings. Empowerment, which simply means ‘gaining control’, has been defined by [

5] as a process by which someone without power gains control over their lives, and this control extends to material assets, ideology, and intellectual resources. It ranges from being defined as a primarily individual process of taking control and responsibility over one’s life and situation to being defined as a political process of granting human rights and social justice to disadvantaged groups—to women’s development mentally and physically in capacities, power, or skills for them to operate meaningfully in their social milieu, thereby experiencing a more favorable level of social recognition and subsequently enhancing their economic status [

6]. Empowerment can have an individual and a collective focus. Individually, the focus is on women’s self-realization and each woman’s ability to control her life both inside and outside the home. At the collective level, the capacity for individual self-realization depends, to a greater or lesser extent, on the extent to which women organize themselves as a group and work together to respond to the multiple layers of subordination to which they are subjected as a category [

7]. In our contemporary society, women are not just a subset of disempowered subgroups (the poor, ethnic minorities, etc.); they are an overarching human category that overlaps with all these subgroups. More importantly, the family and inter-family relations have always been the primary focus of women’s disempowerment, which means that attempts to empower women must consider the impact of policy changes not only at an international or national level but also at a family level. Women’s empowerment requires systemic change, not only of all institutions but also and especially of those that reinforce patriarchal structures [

8]. Women are said to be economically empowered when they have equal access and control over economic resources and opportunities, and the relative ease with which women have access to decision-making roles and can mobilize available legal, economic, social, and political capital to make and take decisions that affect their lives and those of others around them [

9]. The conceptualization of women’s empowerment is based on [

10] ‘the expansion of people’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them.’ Kabeer’s identifies three interrelated dimensions that underpin the ability to make choices: resources, agency, and achievements.

Globally, women comprise about 49.58 percent of the world’s population [

11] and, according to the UN women report in 2022, about 383 million women and girls live in extreme poverty, compared to 368 million men and boys. More than 8 in 10 of this population live in sub-Saharan Africa (62.8 percent), Central Asia, and Southern Asia (21.4 percent). They further explain that if current trends continue, by 2030, more women and girls will be living in extreme poverty than today. Evidence shows that empowering women is a key strategy for poverty reduction, thereby reducing households’ vulnerability to poverty and food insecurity [

12,

13,

14]. The 2017 Oxfam report explains that gender inequality is one of the oldest and most pervasive forms of inequality in the world, denying women their voice, devaluing their work, and making women’s position unequal to men’s from the household to national and global levels [

15]. Economic disparity is fueled by gender inequality, which makes women more likely to be underpaid, to work in vulnerable conditions, and to be excluded from politics. Due to their inferior status in society, women also lack protection from violence and access to resources such as power, money, land, and other assets, and they often have limited access to political, health, and education programs [

16]. In recent years, despite some tangible progress to change, many countries are still lagging in achieving women’s economic equality with men, and women are still more likely to live in poverty than men. Building prosperous, harmonious societies and eradicating poverty and exclusion are significantly hampered by inequality. Globally, policymakers now largely agree that growing and persistent inequality is harmful for nations and individuals—and that this can be prevented by government action [

16].

There has been great interest from many international organizations such as the USAID, Oxfam, UN Women, the World Bank, governments, and private organizations to support the achievement of SDG 5 [

17]. Empowering women and enhancing women’s status can play an important role in achieving many development programs and can help bring about positive social transformation [

18]. Women’s economic empowerment would also have a positive impact on economic growth, with evidence showing that economic growth increases when women and men participate more equally in the economy [

19,

20,

21,

22]. This is essential for realization of women’s rights, poverty reduction, and the achievement of broader development goals [

23].

The SDGs 2022 report found that less than half of the data needed to monitor Goal 5 are currently unavailable, highlighting the need for greater investment in gender statistics. Based on this reality, this article aims to provide an overview of research carried out in the field of women’s empowerment after the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, through a bibliometric approximation of selected scientific articles. This article seeks to provide answers for the following research questions.

What are the trends in the field of women’s empowerment, considering the descriptive analysis of scientific publications?

What has been the annual evolution of scientific publications, co-occurrence analysis, and topic trends during 2015–2022?

Where does the interest of researchers lie as regards women’s empowerment over these years?

Based on the research questions above, this study seeks to make several positive contributions from our findings that would help advance the achievement of SDG 5. Firstly, this study will serve as guide for policymakers who are actively involved in creating policies and programs to support women’s empowerment, gender equality, and growth opportunities for women. Working policies could be put in place if there is enough knowledge about the current state of women’s empowerment, as well as what has been in the past and how to bridge inequality gaps in order to make this goal achievable. Another important contribution that could be derived from this paper is the in-depth academic knowledge from the findings and results presented, displaying the interests of researchers over the years on this topic and thereby adding to the wealth and volume of research and body of knowledge in general.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, bibliometric analysis was used to interpret the trends in academic production on women’s empowerment following the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. Bibliometrics helps in depicting the history and the general state of the art of a specific research field or topic while considering written production as the major formal channel of communication among scientists [

24]. This analysis involves the use of mathematical and statistical methods to investigate the literature selected [

25]. Bibliometric analysis has gained immense popularity in recent years [

26], and its popularity can be attributed to the advancement, availability, and accessibility of bibliometric software such as VOS viewer, Leximancer, Gephi, and scientific databases such as Scopus and the Web of Science [

27].

The systematic review of this study involved four main steps, including data collection, data cleaning, data formatting, and data analysis. First, the literature to be reviewed, which comprised the basic documents of the data collection—‘core dataset’—was identified using the Web of Science (WoS), which is widely used for meta-analysis studies [

28] and is known for its high-quality papers [

29]. In the Web of Science, the topic search (TS) option allows for a search of the title, abstract, author keywords, and keywords, plus fields of the database [

30]. The search query used to obtain the primary dataset is given below.

The keywords above were used to generate a corpus from the WoS, from which the study results were based. A search was carried out on 6 December 2022, where a total of 1465 studies were obtained; after cleaning and formatting, 1095 articles were retained. Data analysis was performed using R-studio and VOSviewer, which are well-known statistical tools used for carrying out bibliometric analysis. The R programming language provides a simple bibliometric analysis package for the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases, performing mathematical statistics on authors, countries, keywords, and journals. VOSviewer software version 1.6.20 is a convenient tool for visualizing co-occurrence networks, which helps to map the knowledge structure in a scientific field [

31].

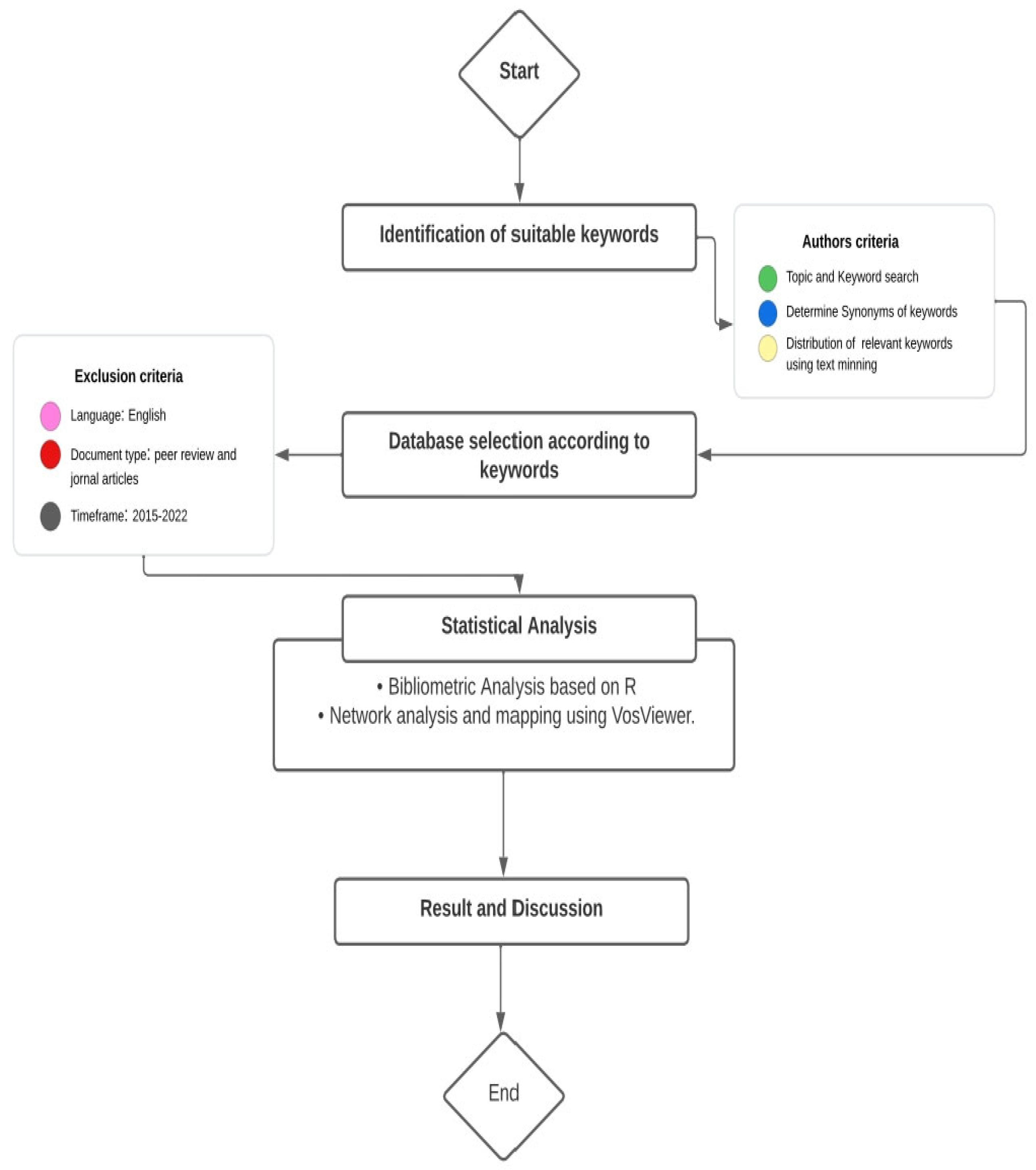

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance to the nature of the review using inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were based on three main factors, namely, document type (journal articles), language (English), and publication timeframe (from 2015 to 2022). The timeframe was linked to the period in the year 2015 when the SDGs were signed, globally accepted, and established. The articles included in this study were those that were most appropriate to the topic, exploring the different aspects of women’s empowerment within the selected period. It is crucial to understand that the data used were based on a global search for scientific productions during the relevant time periods and by using the keywords that were determined to be the most suitable for this study.

Figure 1 shows the workflow of the steps taken in this research study.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 below provides a summary and insight into the characteristics of the data used in this research. The research interests lie in the production of scientific research related to women’s empowerment after the year 2015, when the Sustainable Development Goals were established. The required dataset was carefully selected according to strict criteria, and a total of 1095 documents were selected. Most of the selected documents were likely to be highly cited and of high quality, as indicated by an average of 4945 citations per document. The most common article types in the corpus were review articles, early access articles, and book chapters with 997, 52, and 38 of these included, respectively. A significant increase in collaboration between authors and countries can be seen in the 3315 author appearances and the 3.28 collaboration index. The basic details of the corpus are summarized below.

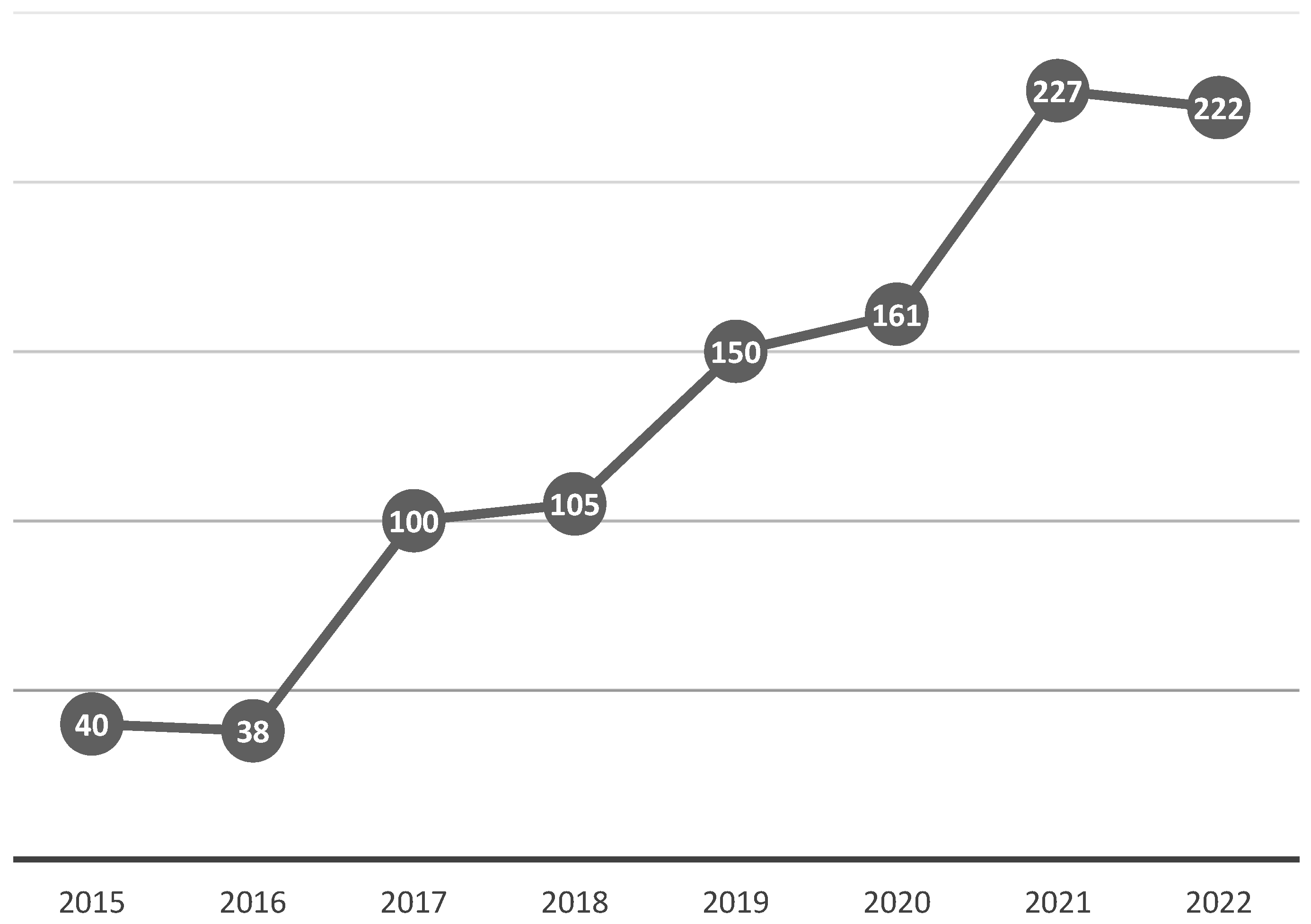

3.2. Annual Scientific Production

The development and progress of research, specifically as it relates to women’s empowerment in this paper, is explained by scientific output. From 2015 (n = 40), there has been consistent growth and progression, with the largest development and leap occurring in 2017 (n = 100), and the most publications being recorded in 2021 (n = 227). According to the corpus used, research also saw an annual growth rate of 27.74%, demonstrating that researchers are becoming increasingly interested in issues pertaining to the advancement of this area.

This growing trend, shown in

Figure 2 below, also reflects the interest shown by many researchers in this field as concerns the exploration of more knowledge on how Sustainable Development Goal 5 can be achieved, which would in turn reflect gender equality and women’s empowerment. It is also important to establish that, from our findings as seen, there has been growth in scientific production, and, as 2030 draws closer, there will likely be more studies and literature produced in the nearest future exploring the extent to which SDG 5 has been achieved.

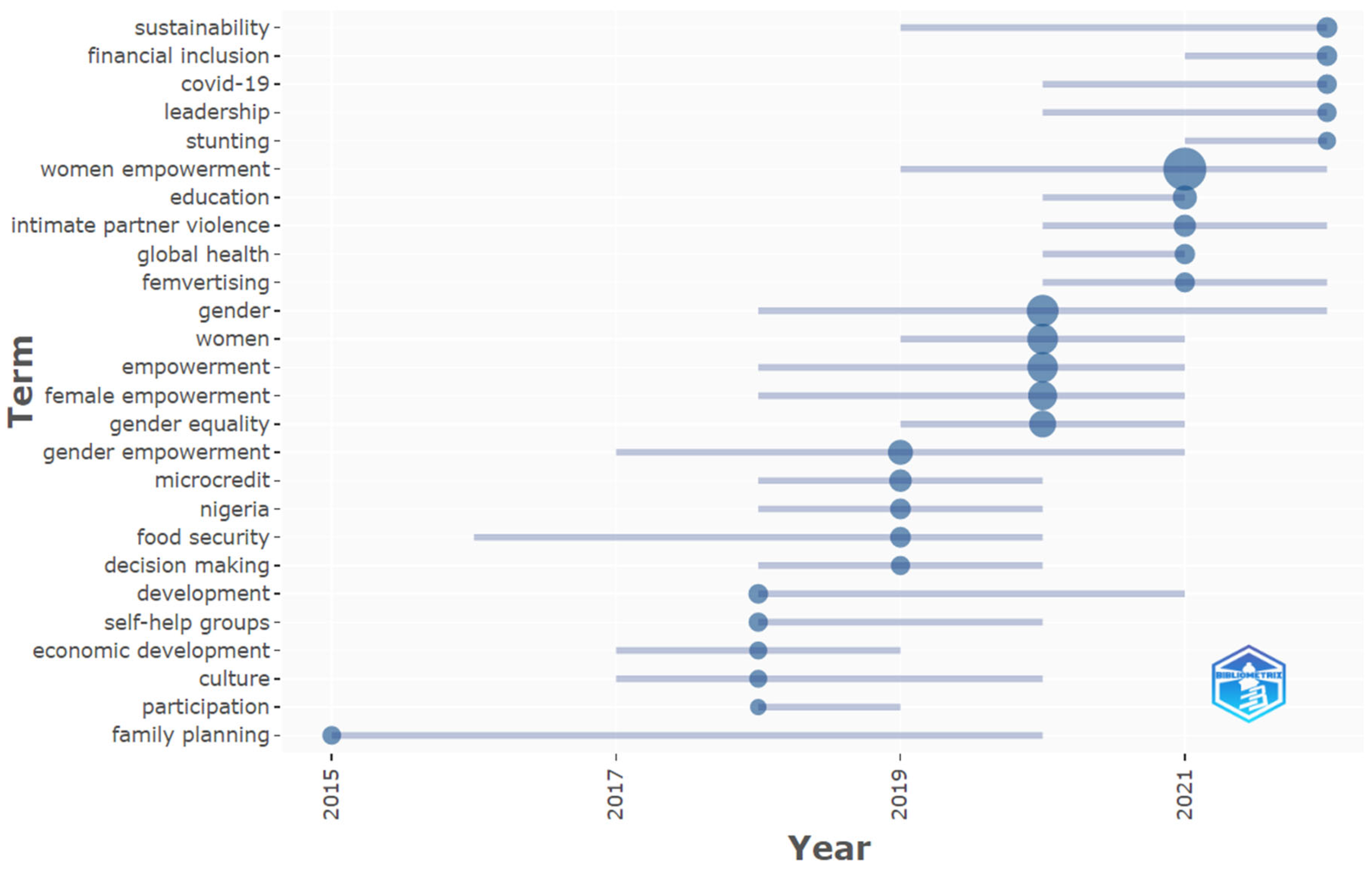

Notably, there were also top terms, as shown by the trend topic analysis in

Figure 3, which were differentially important keywords that were not part of the initial search pattern but became paramount in this topic. These include ‘sustainability’, ‘financial inclusion’, ‘leadership’, ‘education’, ‘femvertising’, ‘decision-making’, ‘culture’, and ‘family planning’. In addition, many of these terms are seen as highly correlated with the level of women’s empowerment, [

32] indicating that education has a greater impact on women’s ability to be financially independent, take on leadership positions, and make health-related decisions such as family planning. Furthermore, increasing women’s financial inclusion is particularly important, as women disproportionately experience poverty due to the unequal division of labor and lack of control over economic resources. Such access for women is essential for inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction [

33]. According to Countdown 2015 Europe, family planning and access to the use of contraceptives is one of the routes to achieving women’s empowerment. They further explained that a strong correlation exists between the increased use of family planning and women’s growing decision-making power in the family, also improving girls’ opportunities for education.

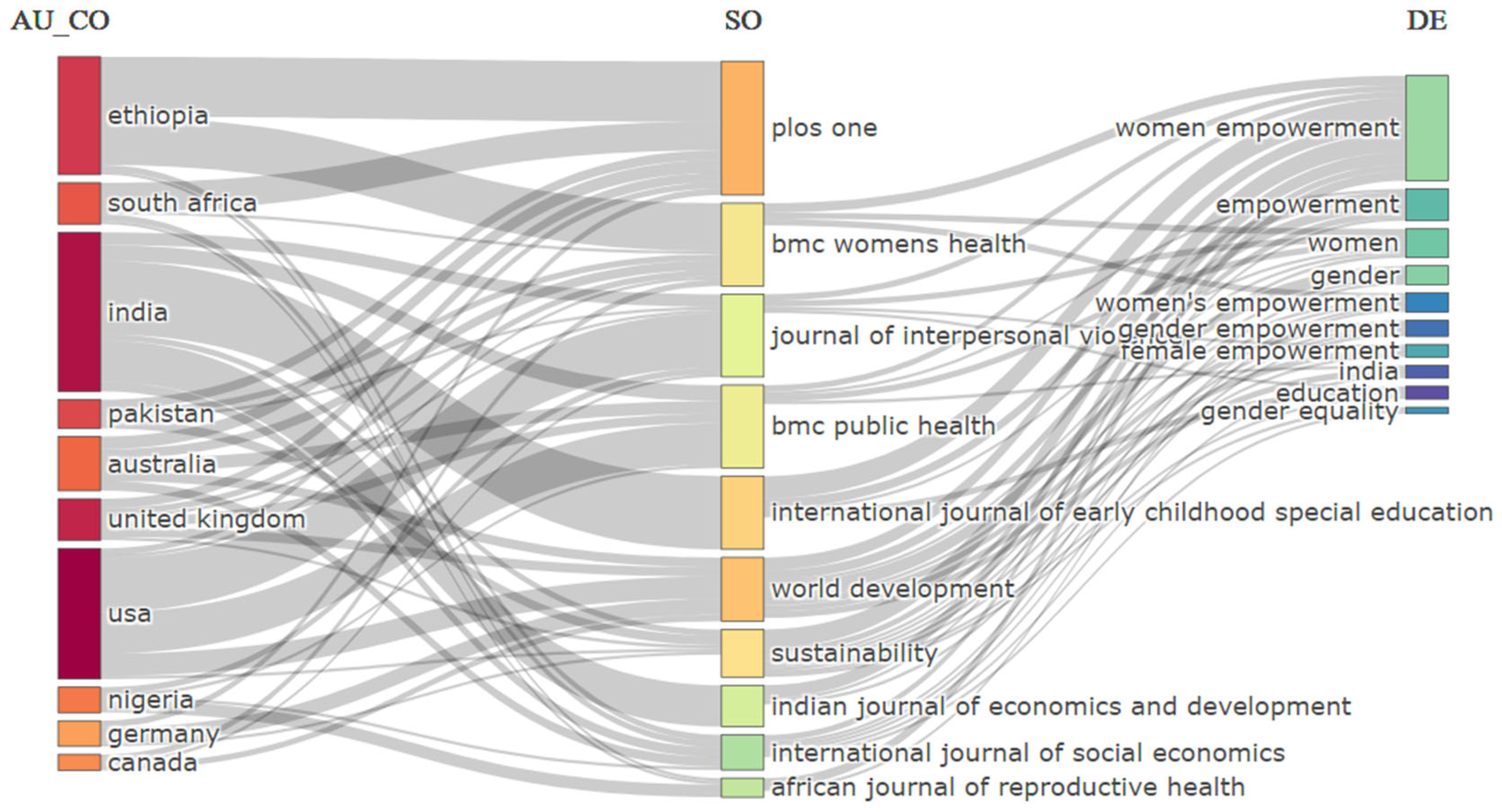

3.3. Three-Field Plot Analysis on Women’s Empowerment

The influx and outflow of the scientific literature, based on the three chosen fields, can be seen using a Sankey 3-point plot diagram. This representation makes it easier to understand the crucial contributions that each of the chosen fields made to the flow system. The top 10 countries leading the research in the study field by author nationality, the primary research areas (keywords), and the publications that mostly published the papers were used to generate the diagram. The thicker rectangles indicate greater frequency, whereas the connecting nodes, inflows, and outflows indicate more connections with more and thicker nodes [

34].

As shown in

Figure 4, scientific research on women’s empowerment is dominated by countries such as Ethiopia, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Nigeria, Germany, and Canada. It is important to note from these findings that about half of these top countries are from the Global South or are developing countries, while others are from developed countries, establishing the importance of women’s empowerment to both economies as further development emerges [

35]. The results also revealed that the issue of empowering women and girls is being widely addressed by many nations of the world, with these knowing full well that women are part of the pillars of growth of any economy, irrespective of the economic status of such country.

3.4. Co-Occurrence Analysis

Co-occurrence analysis focuses on analyzing counts of co-occurring entities within a collection of units. It is used to study the potential relationship of two bibliographic items that appear in the same dissertation [

36] and explain the collective interconnections of key texts based on their paired presence [

37]. This analysis method has become widely used during the last two decades [

38,

39]. A map was generated based on the author keywords, and their weight was calculated based on the total link strength for this study.

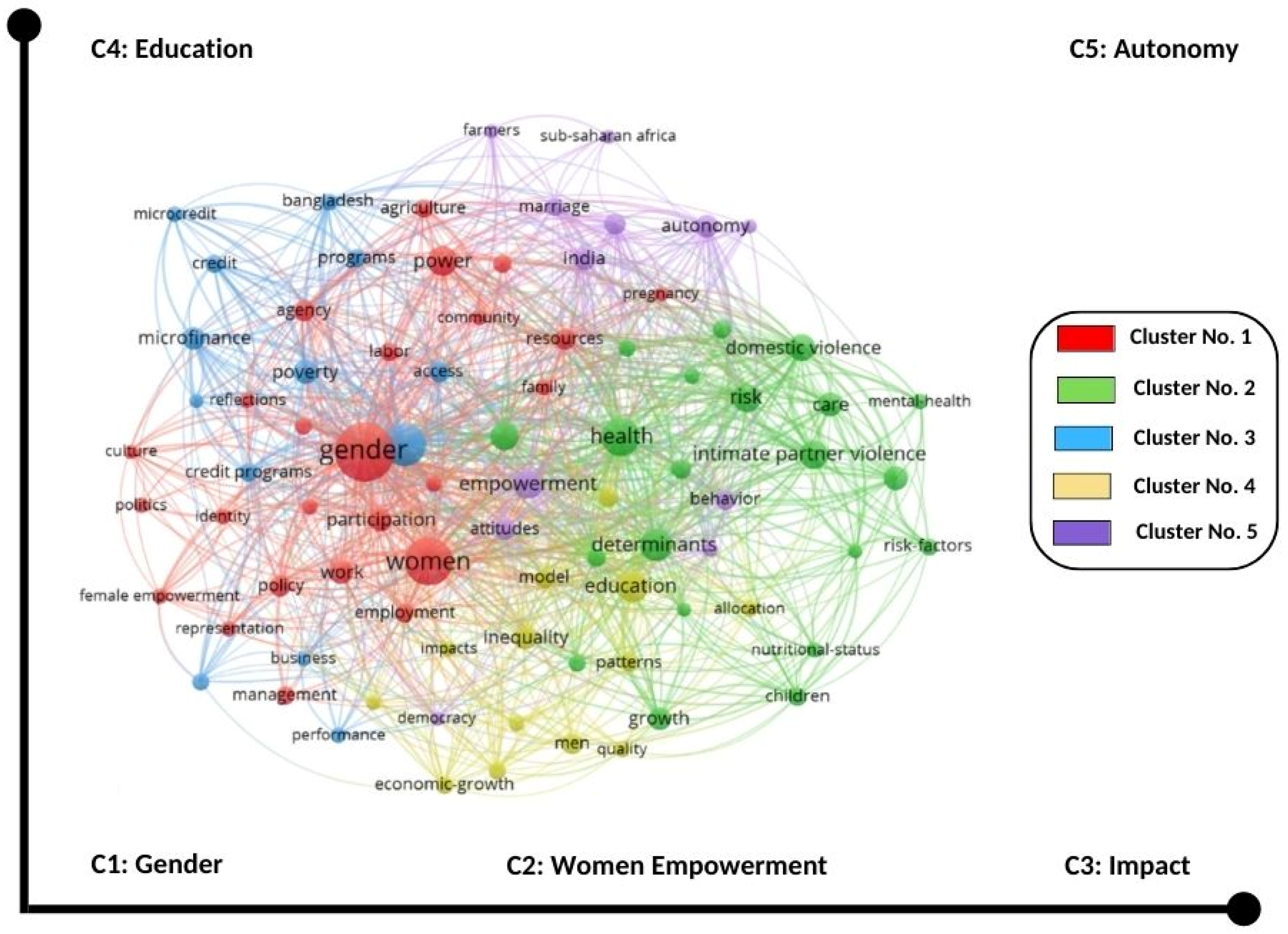

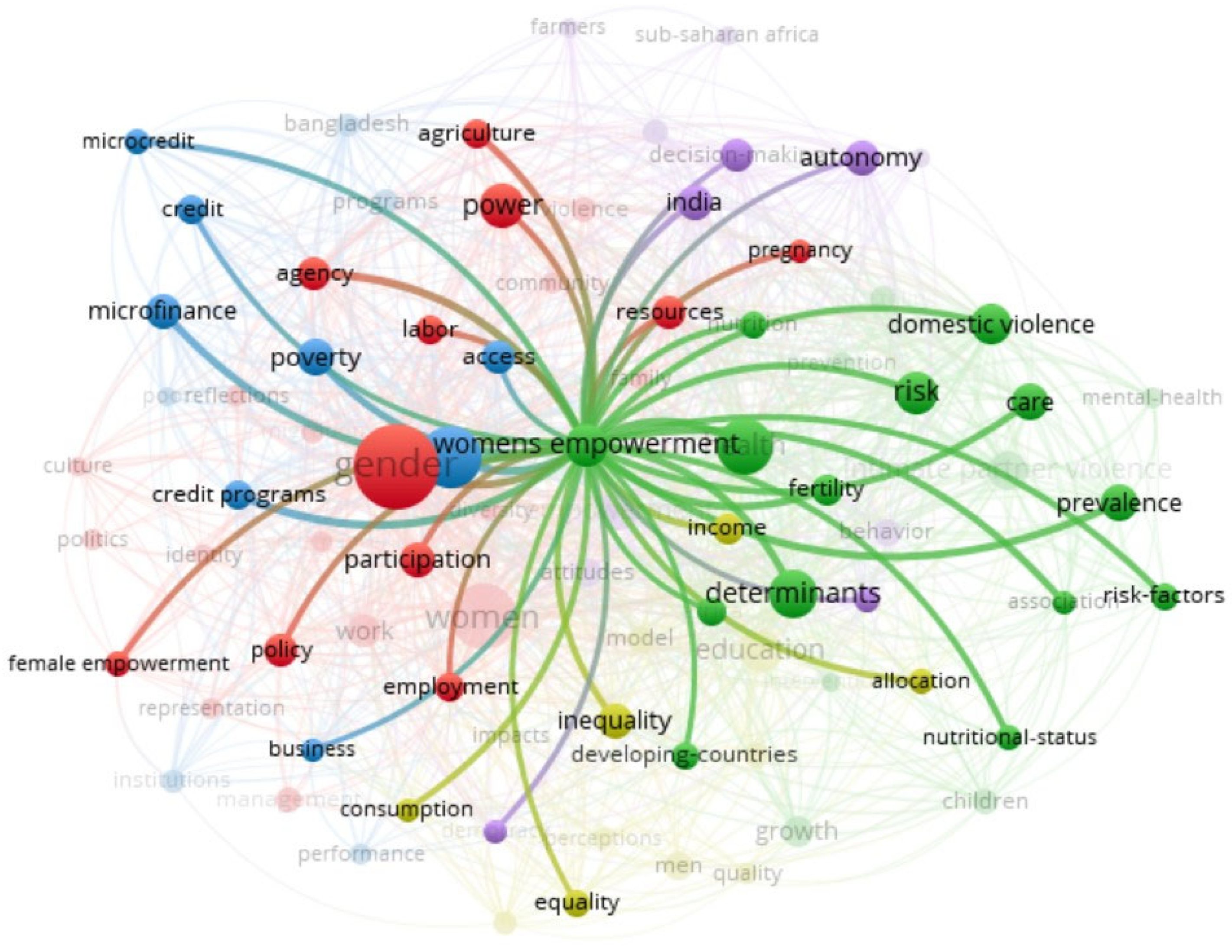

As revealed in

Figure 5, network visualization included five main clusters; these clusters were developed and generated by the VOSviewer software 1.6.20 based on the interconnections identified. The weight of these keywords was measured in terms of total strength, and a high total strength indicated more frequency of occurrences of the keywords in at least five or more documents. The keywords that have highest occurrences in each cluster included gender, women empowerment, impact, education, and autonomy, respectively. These keywords have been seen to have strong connection with women’s empowerment studies and were frequently used in most of the papers analyzed. This visual analysis can be seen below in

Figure 6.

Furthermore, on the co-occurrence network diagram, there are strong connections in research studies related to women’s empowerment, with research work on various important issues such as poverty, gender, domestic violence, autonomy, credit programs, fertility, income, resources, economy, inequality, power, participation, and developing countries, among others, giving us a better understanding of the researchers’ interests and how they are centered around the issue of women’s empowerment.

The list of issues discovered from this finding further corroborate many studies that have found links to positive impacts on women’s empowerment. According to Bolis and Hughes [

40], they provided an insight into the relationship between women’s economic empowerment and domestic violence, explaining that if a woman is economically independent, i.e., has access to income or increased sources of income, it may reduce her risk of violence because her economic dependence is reduced. In the same light, Mengstie [

41] explained that the amount of credit services accessed has a significant impact on women’s economic empowerment. The provision of credit services helps to improve the economic condition of female clients, and women who have received more credit are more likely to achieve higher levels of economic empowerment than those who have received low amounts of credit.

3.5. Mapping of Topic-Evolution with Thematic Analysis

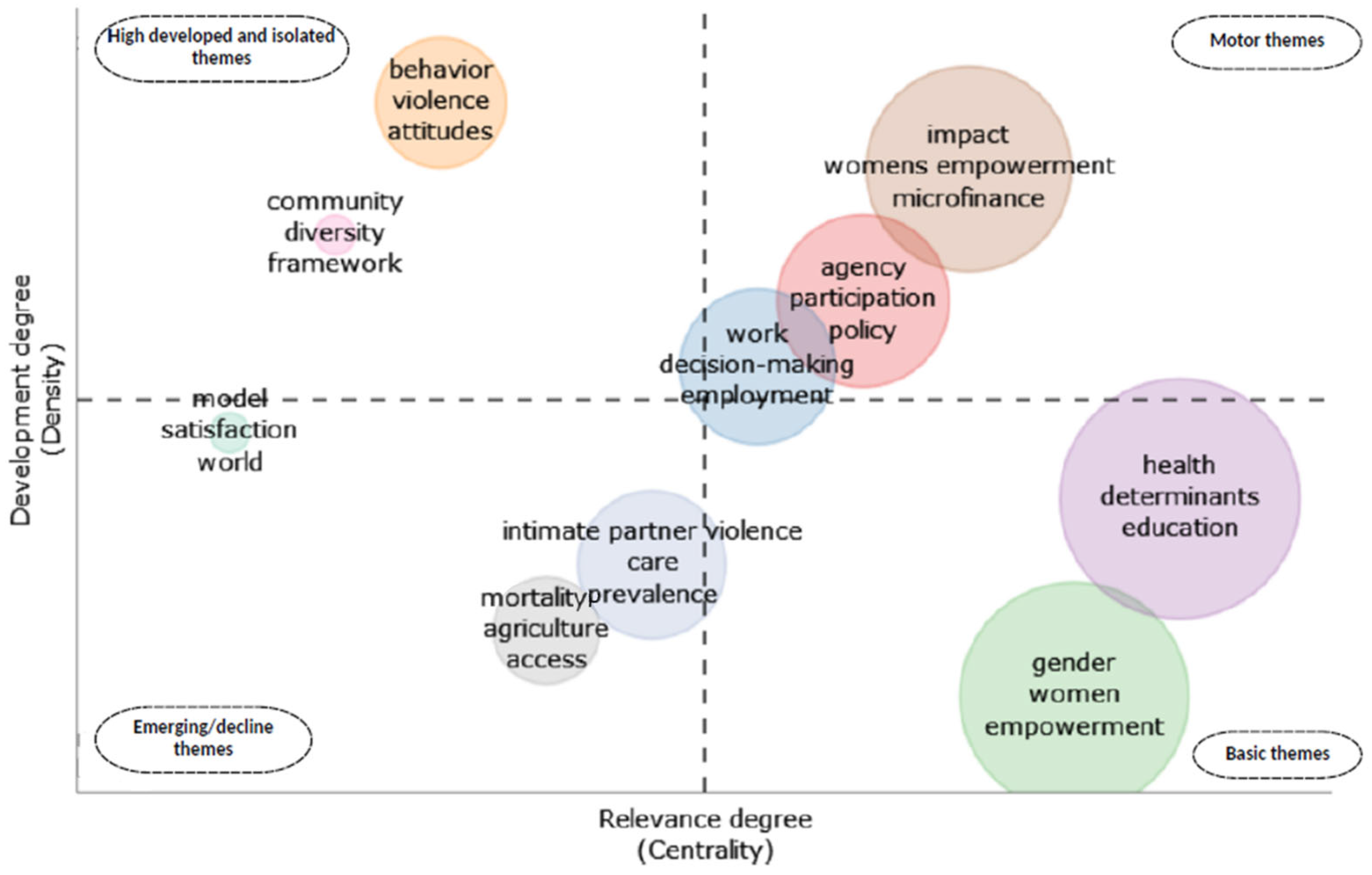

Thematic analysis is a method for studying the conceptual structure of a certain research subject [

42], generating keywords from textual content and categorizing them based on their importance to a larger network, which is then displayed on a graph [

43]. This analysis enables the identification of subgroups of strongly connected phrases, where each subgroup corresponds to a point of interest or a specific research topic within the examined collection. After analysis, the results are then plotted on a strategic or thematic diagram [

42] in accordance with the centrality and density of each cluster or theme, which is also known as Callon’s centrality and Callon’s density [

44]. Callon’s centrality can be read as the importance of the topic in the whole research domain, while Callon’s density can be read as a measure of the topic’s development.

This graphical representation allows for the highlighting of four typologies of themes depending on the quadrant in which they are mapped.

Motor themes are in the upper-right quadrant and have higher values of centrality and density, meaning they are well developed and relevant for structuring a conceptual framework of a research domain.

Basic themes are in the lower-right quadrant and are characterized by higher values of centrality and lower values of density, indicating that they are crucial for the domain and spread to other broad issues in many research areas of the domains.

Emerging or declining themes, in the lower-left quadrant, have lower values of centrality and density, meaning they are not fully developed and are marginally interesting for a domain.

Themes in the upper-left quadrant are known as highly developed and isolated themes, with lower values of centrality and higher values of density, meaning that they are strongly developed but still marginal or of limited importance for a domain or field of interest.

Figure 7 explains the discourse on women empowerment research development and emerging interests around the topic. It was observed that there exist quite a few topics that fall in the motor quadrant with high centrality and density. Topics such as impact, women’s empowerment, microfinance, work, decision making, and employment indicate that the topics are of great relevance and have been developed greatly because of researchers’ interest in them, and they can be seen as fundamental for study.

The basic themes known to have a high centrality value include keywords such as health, education, gender, women, and empowerment. This means that, although some of these words are very important for this research area, they are not limited to this area but extend to other areas where they are used. The emerging or declining theme quadrant has topics such as agriculture, access, care, intimate partner violence, and mortality. These themes are seen to be gradually moving towards the motor theme quadrant, suggesting that they will become more relevant and developed in this research area in a few years’ time. It was also seen that other keywords under this quadrant such as model, satisfaction, and world are quickly moving to the upper-left quadrant. The highly developed and isolated themes with keywords such as behavior, violence, attitude, community, diversity, and framework are known to be well developed around this research domain but with limited interest.

4. Discussion

A bibliometric approach is a result of academic curiosity and is about gaining a broad perspective of the scientific production that has evolved around a topic. This approach allows us to understand the features of the publications produced, opening doors for new ideas and paths of inquiry. This paper adopted this analysis approach to examine the current trends of research in women’s empowerment studies after the Sustainable Development Goals of 2015. Based on the visualization analysis of 1095 pertinent papers, we discovered significant findings that shed light on the topic’s state and trends now. The findings also support the fact that relevant publications in this area have been growing gradually, even though there is need for more research in this field, buttressing what the SDG report said in 2022 about the need for greater investment in gender statistics [

45].

As seen in the results, scientific production experienced about a 2.6-fold increase in 2017 from 38 to 100 papers, reflecting a notable evolution in the number of publications, and, thereafter, there has been consistent growth in production. According to [

46], research and studies on and around the Sustainable Development Goals will continue and develop in the next years as scientific interest grows because the assessment of the accomplishment of these objectives is scheduled for the year 2030.

It is also important to note that the growth experienced and observed has both been in the developing and developed nations as shown by the 3-point plot analysis in

Figure 4. This clearly shows that this topic is widely researched in many nations and continents around the world. It has further revealed that both developed and developing countries are concerned about the problem of gender inequality, though this is more prominent in developing nations [

35]. The persistence of gender-stratified economic structures, such as low access to paid work and the over-representation of working women in lower-paid, casual, part-time, and irregular market activities, testifies to the persistence of gender disadvantages worldwide. [

33]. Women from many of the less-developed nations of the world such as India, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Nigeria, etc., are even more at a disadvantage due to cultural, social, patriarchal family system, religious, and psychological factors, which affect the success of women’s empowerment in these nations [

7,

47,

48]—hence the need for many of these nations to seek gender equality and balance.

Regarding the worldwide spread of publications, it is fascinating to highlight that, among the countries with the highest level of scientific production, five of the world continents are represented. The results also show that, as regards scientific journals, a good number of articles are published in high-impact journals such as

Sustainability and

World Development, and some publication has also been made in journals representing less developed nations, such as Africa and India. In summary, this shows that interest in this topic is widespread, both in terms of nations and publications, in line with [

8], who said that the empowerment of women has been widely acknowledged as an important goal in international development and has been recognized as a needed tool in policy and project implementation.

Within the clusters of study themes, we were able to find dominating terms such as autonomy, power, employment, and participation, all of which have a direct relationship to gender equality and are current subjects of discussion in scientific areas. These keywords are part of what forms the research base for the National Demography Health Survey, which is conducted for many countries, examining the empowerment status of women [

49]. Women’s economic autonomy involves the possibility of controlling assets and resources [

50]. Autonomy, which can also be linked to power, refers to women’s ability to make uninfluenced decisions, ranging from decisions about their health, control over their earnings, and general influence over family and social matters. It was revealed that employment and earnings have a great positive boost on the improvement of the empowerment status of women, because employed women are more independent, productive, and innovative [

51]. Similarly, ref. [

52] explained that women who have access to better quality employment, higher levels of education, and, in some contexts, to assets and independent associational life are more likely to decide how to spend their income and make decisions about their own health. In addition, they tend to gain respect within the community, participate in politics, and express support for gender-egalitarian attitudes [

52]. Inasmuch as this study offered valuable insights, we are certain that additional scientific study and literature are required to broaden and augment the current body of knowledge.

Research Limitation

There were few restrictions on the keyword search; the size of the corpus examined in this study was dependent on the keywords chosen at the time of the study. It is possible that adding or removing a less important term would have affected the results we obtained. Our choice of keywords was based on our interests, and it is possible that we may have omitted some other important terms that affected the size of the corpus. For example, after analysis, we found that some keywords, such as gender equality and autonomy, were much more common and could have provided a robust database if they had been included in the search when it was conducted. As authors, we are aware that there may have been more developed and researched areas that were not fully covered but only briefly mentioned as part of women’s empowerment in relation to SDG 5.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes the importance of this research, as it provides in-depth knowledge of publication trends in women’s empowerment studies in light of the Sustainable Development Goals and offers a starting point for researchers wishing to explore this topic from different angles. We must bear in mind that, according to the results of the bibliometric approach, this field is still evolving, with a progressive and continuous expansion in both emerging and developed countries worldwide.

The results from the findings have specifically shown and have revealed the extent to which research has been conducted on the topic of discussion. Our findings established strong connections that have been linked to women’s empowerment studies based on the cluster analysis—namely, gender, women’s empowerment, impact, education, and autonomy. In addition to this, the analysis further reveals that there are many factors that have great impact on empowering women, such as nutritional status, income, fertility, resources, and credit programs, which, if properly considered and incorporated into policies and programs, would positively affect the empowerment status of women on all levels. This topic has also generated great interest at all local, national, and international levels, with the aim of achieving gender equality and balance in many nations of the world. In terms of scientific publications by countries in recent years, India, Ethiopia, the USA, Australia, South Africa, Pakistan, the UK, Germany, Nigeria, and Canada are at the top, whereas most of the relevant scientific journals belong to developed countries.

In conclusion, in relation to Sustainable Development Goal 5, there has been an incredible increase in scientific productivity on women’s empowerment and gender equality in recent years, following the adoption of the goals in 2015, with a high level of acceptance from both developed and developing countries, further confirming that there is a need for all the nations of the world to rise to the occasion of implementing favorable policies that would foster the achievement of this goal. The findings have also offered a significant suggestion regarding the need for more research and data information with literature documentation to showcase the impact of SDG 5 on the targeted gender and to re-establish the impact of many policy recommendations that have been proposed in the past or are currently being implemented.