Act like There Is a Tomorrow—Contact and Affinity with Younger People and Legacy Motivation as Predictors of Climate Protection among Older People

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Contact

2.2. Affinity

2.3. Legacy Motivation

3. Present Studies

Study 1

- Hypotheses

4. Methods

4.1. Data Collection and Participants

4.2. Measures

4.3. Planned Statistical Analyses

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

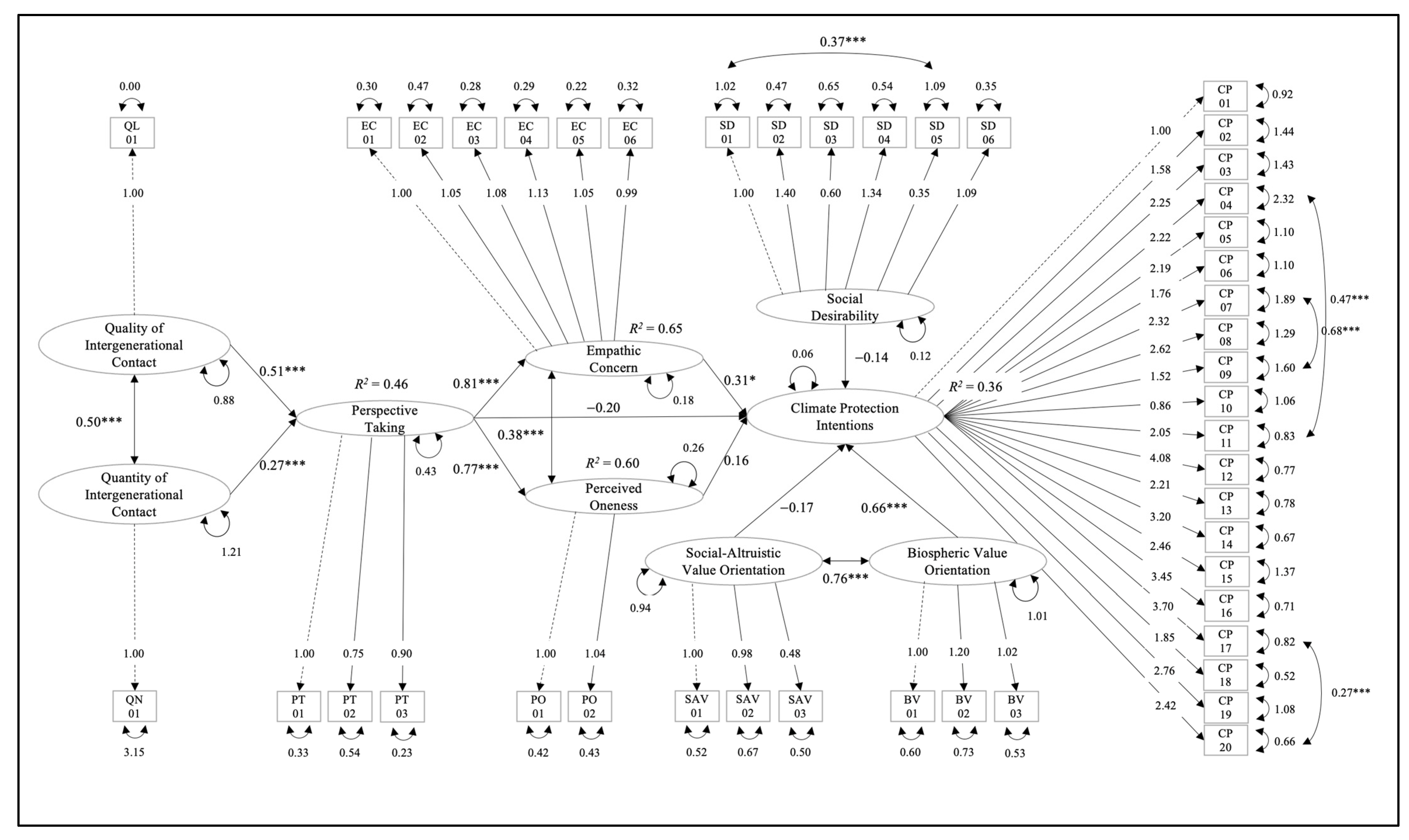

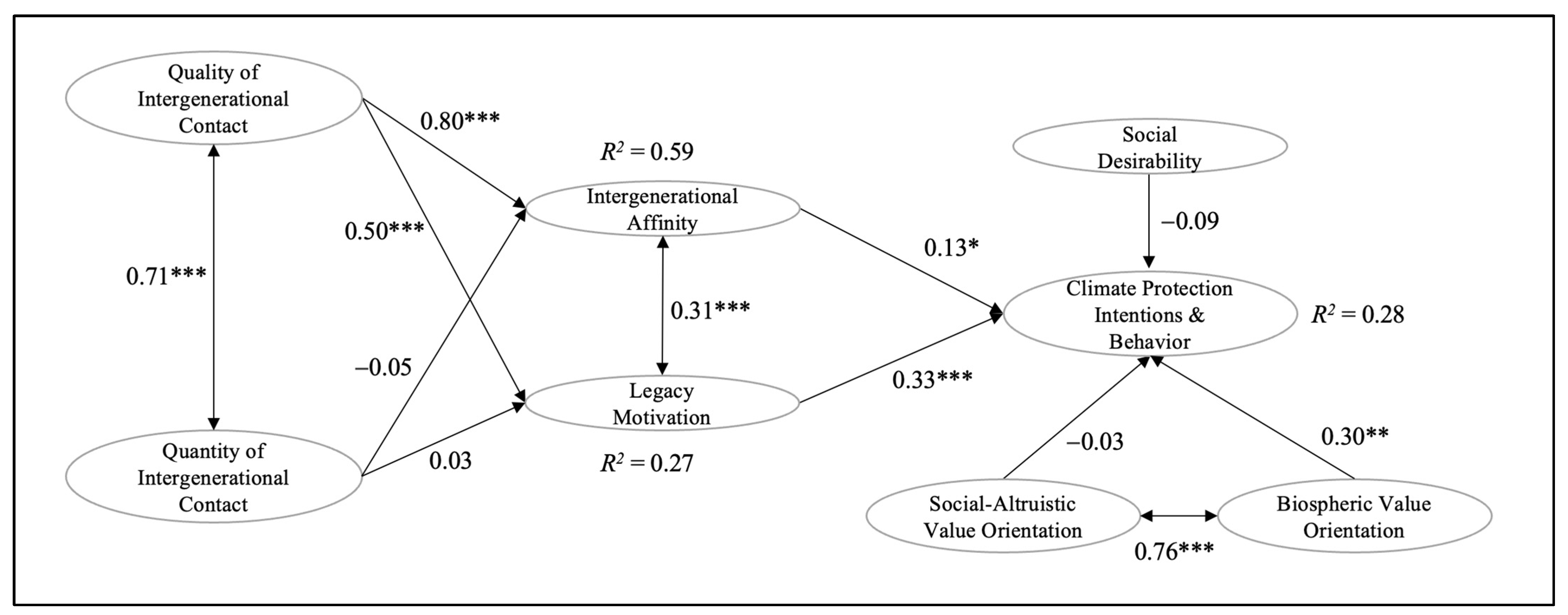

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

Study 2

- Hypotheses

7. Methods

7.1. Data Collection and Participants

7.2. Procedure

7.3. Measures

7.4. Manipulation of Perspective Taking

7.5. Planned Statistical Analyses

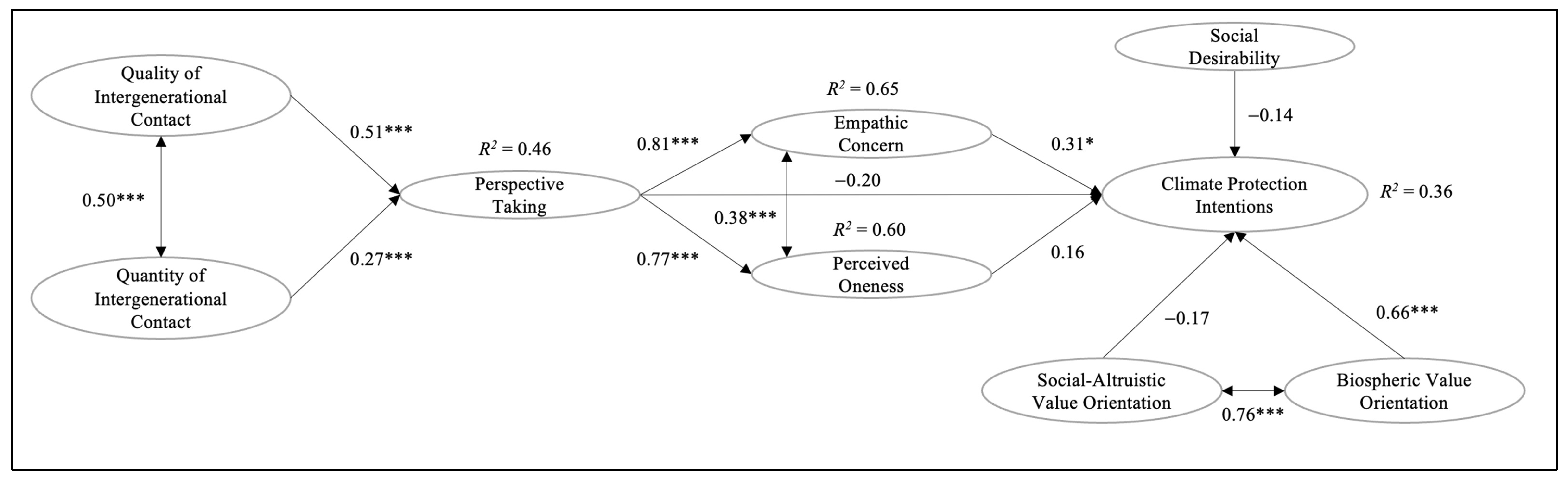

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

8.2. Evaluation of the Intervention

8.3. Structural Model

9. Discussion

10. General Discussion

10.1. Prediction of Climate Protection Intentions and Behavior

10.2. Limitations

10.3. Implications for Future Research and Practice

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| QN01 | How much contact do you have with young people (e.g., as neighbors, as friends and family, at leisure activities)? | 1 = none at all 5 = a great deal |

| Study 1 | ||

| To what extent do you experience the contact with young people as… | ||

| QL01 | …equal? | 1 = not at all 5 = very |

| QL02 | …voluntary? | |

| QL03 | …intimate? | |

| QL04 | …superficial? | |

| QL05 | …pleasant? | |

| QL06 | …competitive? | |

| QL07 | …cooperative? | |

| Study 2 | ||

| QL01 | How would you rate your contact with young people? | 1 = very negative 5 = very positive |

| The following questions relate to your attitude toward and relationship with young people. | ||

| Perspective Taking | ||

| Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements. | ||

| PT01 | It is easy for me to put myself in the shoes of young people. | 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree |

| PT02 | I can imagine how I would think or feel if I were young again. | |

| PT03 | I can imagine the feelings and thoughts of young people. | |

| Perceived Oneness | ||

| PO01 | From the seven graphs, please select the one that best describes your relationship with young people. | 7 pairs of increasingly overlapping circles |

| PO02 | Please indicate the extent to which you would use the term ‘we’ to describe yourself and young people. | 1 = not at all 5 = extremely |

| Empathic Concern | ||

| Please describe how strongly you feel each emotion described toward young people. | ||

| EC01 | Sympathetic | 1 = not at all 5 = a great deal |

| EC02 | Moved | |

| EC03 | Compassionate | |

| EC04 | Tender | |

| EC05 | Warm | |

| EC06 | Soft-hearted | |

| Please indicate to what extent the following statements apply to you. | ||

| LM01 | It is important to me to leave a positive legacy for young generations. | 1 = not at all 5 = a great deal |

| LM02 | It is important to me to avoid leaving a negative legacy for young generations. | |

| LM03 | It is important for me to leave a positive mark on society. | |

| LM04 | It is important to me to leave a good legacy for those who come after us. | |

| The following questions are about different climate protection behaviors and whether you plan to implement them in the near future. If a question does not apply to you, e.g., because you do not have a car that you can replace, please check “not applicable”. Only in Study 1: If you have already been performing a behavior for some time or for example have already replaced your car, please tick “I have already done this/I am already doing this”. | ||

| In the near future, are you planning to … | ||

| CPI01 | …repair broken things whenever possible instead of disposing of them and buying new ones? | Study 1: 1 = no, definitely not 2 = no, probably not 3 = yes, probably 4 = yes, definitely 5 = I have already done that/I am already doing this + not applicable Study 2: 1 = no, definitely not 5 = yes, definitely + not applicable |

| CPI02 | …buy an electric car instead of a car with a combustion engine? | |

| CPI03 | …give food to other people/institutions before it spoils (e.g., via food sharing initiatives)? | |

| CPI04 | …maintain moderate room temperatures of no more than 20 °C in winter? | |

| CPI05 | …avoid private air travel altogether? | |

| CPI06 | …eat a vegetarian diet? | |

| CPI07 | …refrain from using a private car? | |

| CPI08 | …offset your carbon emissions through compensation payments to climate protection projects (e.g., via Atmosfair, myClimate or Primaklima)? | |

| CPI09 | …use public transport or the bicycle instead of the car? | |

| CPI10 | …switch off appliances when you are not using them instead of putting them into stand-by mode? | |

| CPI11 | …save hot water (e.g., by taking shorter showers)? | |

| CPI12 | …take part in climate protection activities (e.g., planting trees)? | |

| CPI13 | …purchase green electricity? | |

| CPI14 | …invest money in a social-ecological bank (e.g., GLS-Bank or UmweltBank)? | |

| CPI15 | …vote for candidates or parties in an election because they are committed to strong climate protection? | |

| CPI16 | …sign petitions in support of climate protection? | |

| CPI17 | …take part in climate protection protests? | |

| CPI18 | …donate to climate protection projects? | |

| CPI19 | …not buy a company’s products because you believe that this company is damaging the climate? | |

| CPI20 | …be a member of a group whose aim is to protect the climate? | |

| Please indicate to what extent the following statements apply to you. | ||

| SD01 | It has happened before that I have taken advantage of someone. | 1 = doesn’t apply at all 5 = applies completely |

| SD02 | Even if I am feeling stressed, I am always friendly and polite to others. | |

| SD03 | Sometimes I only help someone if I can expect something in return. | |

| SD04 | In an argument, I always remain objective and stick to the facts. | |

| SD05 | I’ve thrown garbage in the countryside or on the street before. | |

| SD06 | When talking to someone, I always listen carefully to what the other person says. | |

| Please indicate the extent to which you consider the following values to be guiding principles of your life. | ||

| SAV01 | Social justice, correcting injustice, care for the weak | −1 = opposed to my values 0 = not important 1, 2 (unlabeled) 3 = important 4, 5 (unlabeled) 6 = very important 7 = of supreme importance |

| SAV02 | Equality, equal opportunity for all | |

| SAV03 | A world of peace, free of war and conflict | |

| BV01 | Environmental protection and nature conservation | |

| BV02 | Being one with nature, being part of nature | |

| BV03 | Respect for the earth, living in harmony with other living beings | |

Control Group Text

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Experimental Condition | Quality of Intergenerational Contact | Quantity of Intergenerational Contact | Perspective Taking (Unadjusted) | Perspective Taking (Adjusted) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| EG 1 | 102 | 4.04 | 1.00 | 106 | 3.07 | 1.17 | 106 | 3.73 | 0.91 | 100 | 3.79 | 0.88 |

| EG 2 | 96 | 4.11 | 0.89 | 98 | 3.21 | 1.04 | 99 | 3.70 | 0.88 | 95 | 3.77 | 0.82 |

| CG | 100 | 4.00 | 0.86 | 103 | 3.18 | 1.09 | 103 | 3.68 | 0.84 | 100 | 3.75 | 0.84 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Intergenerational Contact | 30.19 | 1 | 30.19 | 60.49 | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| Quantity of Intergenerational Contact | 7.45 | 1 | 7.45 | 14.92 | <0.001 | 0.049 |

| Experimental Condition | 0.39 | 2 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.00 |

| Error | 144.74 | 290 | 0.50 |

| Experimental Condition | Empathic Concern | Empathic Concern | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Unadjusted) | (Adjusted) | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| EG 1 | 107 | 3.55 | 0.83 | 101 | 3.59 | 0.80 |

| EG 2 | 98 | 3.71 | 0.74 | 94 | 3.76 | 0.70 |

| CG | 103 | 3.55 | 0.80 | 100 | 3.56 | 0.81 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Intergenerational Contact | 42.94 | 1 | 42.94 | 114.72 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Quantity of Intergenerational Contact | 1.45 | 1 | 1.45 | 3.87 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Experimental Condition | 1.07 | 2 | 0.54 | 1.43 | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| Error | 108.55 | 290 | 0.374 |

| Experimental Condition | Perceived Oneness | Perceived Oneness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Unadjusted) | (Adjusted) | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| EG 1 | 105 | 3.08 | 0.94 | 101 | 3.12 | 0.93 |

| EG 2 | 99 | 3.22 | 0.91 | 95 | 3.28 | 0.86 |

| CG | 103 | 3.10 | 1.01 | 100 | 3.17 | 0.95 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Intergenerational Contact | 15.86 | 1 | 15.86 | 26.88 | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| Quantity of Intergenerational Contact | 23.34 | 1 | 23.34 | 39.57 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Experimental Condition | 0.65 | 2 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.00 |

| Error | 171.65 | 291 | 0.59 |

| Experimental Condition | Climate Protection Intention | Climate Protection Intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Unadjusted) | (Adjusted) | |||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| EG 1 | 107 | 2.64 | 0.76 | 101 | 2.67 | 0.74 |

| EG 2 | 99 | 2.88 | 0.74 | 95 | 2.90 | 0.75 |

| CG | 103 | 2.93 | 0.88 | 100 | 2.94 | 0.86 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Intergenerational Contact | 3.15 | 1 | 3.15 | 5.20 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| Quantity of Intergenerational Contact | 0.14 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.64 | 0.00 |

| Experimental Condition | 4.26 | 2 | 2.13 | 3.52 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Error | 176.05 | 291 | 0.61 |

References

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- IPCC. FAQ 3: How Will Climate Change Affect the Lives of Today’s Children Tomorrow, If No Immediate Action Is Taken? IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/about/frequently-asked-questions/keyfaq3/ (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Zagheni, E. The leverage of demographic dynamics on carbon dioxide emissions: Does age structure matter? Demography 2011, 48, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockemer, D.; Sundström, A. Age Inequalities in Political Representation: A Review Article. Gov. Oppos. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Age Structure. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/age-structure (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- IPCC. Longer Report. In Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- John, A.; Pecchenino, R. An Overlapping Generations Model of Growth and the Environment. Econ. J. 1994, 104, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaval, L.; Markowitz, E.M.; Weber, E.U. How will I be remembered? Conserving the environment for the sake of one’s legacy. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlstone, M.J.; Price, A.; Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. Activating the legacy motive mitigates intergenerational discounting in the climate game. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 60, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A.; Plunkett Tost, L. The egoism and altruism of intergenerational behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 13, 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, P.A. The effects of cognitive and affective perspective taking on empathic concern and altruistic helping. J. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 136, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, B.M.; Glasford, D.E. Intergroup contact and helping: How quality contact and empathy shape outgroup helping. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2018, 21, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, A.D.; Moskowitz, G.B. Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A. Maple trees and weeping willows: The role of time, uncertainty, and affinity in intergenerational decisions. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 220–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadieux, J. Intergenerational Contact Predicts Attitudes Toward Older. Adults through Inclusion of the Outgroup in the Self. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 74, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.M. The reduction of intergroup tensions: A survey of research on problems of ethnic, racial, and religious group relations. Soc. Sci. Res. Counc. Bull. 1947, 57, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.; Hewstone, M. Dimensions of contact as predictors of intergroup anxiety, perceived out-group variability, and out-group attitude: An integrative model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 19, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Eller, A.; Leeds, S.; Stace, K. Intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate, M.; Oethinger, S.; Kuchenbrandt, D.; Van Dick, R. Is an outgroup member in need a friend indeed? Personal and task-oriented contact as predictors of intergroup prosocial behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hässler, T.; Ullrich, J.; Bernardino, M.; Shnabel, N.; Laar, C.V.; Valdenegro, D.; Sebben, S.; Tropp, L.R.; Visintin, E.P.; González, R. A large-scale test of the link between intergroup contact and support for social change. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, N.M. Effects of Age and Interpersonal Contact on Stereotyping of the Elderly. Curr. Psychol. 1998, 17, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousfield, C.; Hutchison, P. Contact, anxiety, and young people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions towards the elderly. Educ. Gerontol. 2010, 36, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Schell, R.; Kaufman, D.; Salgado, G.; Jeremic, J. Social Interaction between Older Adults (80+) and Younger People during Intergenerational Digital Gameplay. In Proceedings of the Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population, Applications, Services and Contexts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Lishner, D.A.; Stocks, E.L. The Empathy—Altruism Hypothesis. In The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior; Schroeder, D.A., Graziano, W.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Sager, K.; Garst, E.; Kang, M.; Rubchinsky, K.; Dawson, K. Is Empathy-Induced Helping due to Self–Other Merging? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, L. The Interplay of Empathy, Oneness and Perceived Similarity in Mediating the Effects of Perspective Taking on Prosocial Responses. (Publication No. 146905452). Ph.D. Thesis, Università di Padova, Padua, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D.; Chang, J.; Orr, R.; Rowland, J. Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Polycarpou, M.P.; Harmon-Jones, E.; Imhoff, H.J.; Mitchener, E.C.; Bednar, L.L.; Klein, T.R.; Highberger, L. Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social Comparison and Social Identity: Some Prospects for Intergroup Behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, S.; Moskowitz, G.B. Evidence for Implicit Evaluative In-Group Bias: Affect-Biased Spontaneous Trait Inference in a Minimal Group Paradigm. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 36, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Prosser, A.; Evans, D.; Reicher, S. Identity and Emergency Intervention: How Social Group Membership and Inclusiveness of Group Boundaries Shape Helping Behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H. Perspective-taking of a similarly-situated single victim increases donations for multiple victims. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2022, 27, e1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A. Thinking about the future: An intergenerational perspective on the conflict and compatibility between economic and environmental interests. Am. Behav. Sci. 1999, 42, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A. Intergenerational identification and cooperation in organizations and society. Res. Manag. Groups Teams 2003, 5, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Sieverding, T.; Merten, M.; Kastner, K. Old for young: Cross-national examination of intergenerational political solidarity. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2023, 13684302231201785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickersham, R.H.; Zaval, L.; Pachana, N.A.; Smyer, M.A. The impact of place and legacy framing on climate action: A lifespan approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A.; Tost, L.P.; Hernandez, M.; Larrick, R.P. It’s only a matter of time: Death, legacies, and intergenerational decisions. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, H.M.; Koval, C.Z.; Wade-Benzoni, K.A. It’s the thought that counts over time: The interplay of intent, outcome, stewardship, and legacy motivations in intergenerational reciprocity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 73, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.; Hinner, J.; Kruse, A. Dialogue between generations–basic ideas, implementation and evaluation of a strategy to increase generativity in post-soviet societies. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 12, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A. Social desirability in environmental psychology research: Three meta-analyses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Bevölkerung im Alter von 15 Jahren und Mehr nach Allgemeinen und Beruflichen Bildungsabschlüssen nach Jahren. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Bildungsstand/Tabellen/bildungsabschluss.html#fussnote-1-104098 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Lolliot, S.; Fell, B.; Schmid, K.; Wölfer, R.; Swart, H.; Voci, A.; Christ, O.; New, R.; Hewstone, M. Chapter 23-Measures of Intergroup Contact. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs; Boyle, G.J., Saklofske, D.H., Matthews, G., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 652–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D. Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 20, 65–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Ahmad, N.Y. Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2009, 3, 141–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Brown, S.L.; Lewis, B.P.; Luce, C.; Neuberg, S.L. Reinterpreting the empathy–altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Smollan, D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A.; Sondak, H.; Galinsky, A.D. Leaving a legacy: Intergenerational allocations of benefits and burdens. Bus. Ethics Q. 2010, 20, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, E.; de Paula Sieverding, T.; Engel, L.; Blöbaum, A. Simple and Smart: Investigating Two Heuristics That Guide the Intention to Engage in Different Climate-Change-Mitigation Behaviors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C.J.; Beierlein, C.; Bensch, D.; Kovaleva, A.; Rammstedt, B. Eine Kurzskala zur Erfassung des Gamma-Faktors sozial erwünschten Antwortverhaltens: Die Kurzskala Soziale Erwünschtheit-Gamma (KSE-G); GESIS—Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften: Mannheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. A brief inventory of values. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 58, 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Fried, L.; Moody, R. Aging, climate change, and legacy thinking. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1434–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Riomalo, J.F.; Koessler, A.-K.; Engel, S. Inducing perspective-taking for prosocial behaviour in natural resource management. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 110, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, J.K.; Luce, C.L.; Neuberg, S.L.; Cialdini, R.B.; Brown, S.; Sagarin, B.J. The effects of perspective taking on motivations for helping: Still no evidence for altruism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Early, S.; Salvarani, G. Perspective Taking: Imagining How Another Feels Versus Imaging How You Would Feel. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, R.A.; Mattos, M.K.; Vranceanu, A.M. Older adults can use technology: Why healthcare professionals must overcome ageism in digital health. Transl. Behav. Med. 2022, 12, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior:How to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale Range | M | SD | ω | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Quantity | 1 to 5 | 3.41 | 1.10 | / |

| Contact Quality | 1 to 5 | 3.59 | 0.82 | 0.89 |

| Affinity | 1 to 5 | 3.44 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| Legacy Motivation | 1 to 5 | 3.63 | 1.11 | 0.93 |

| Social Desirability | 1 to 5 | 4.04 | 0.62 | 0.65 |

| Social-Altruistic Values | −1 to 7 | 5.73 | 1.31 | 0.81 |

| Biospheric Values | −1 to 7 | 5.23 | 1.64 | 0.88 |

| Climate Protection | 1 to 5 | 2.65 | 0.72 | 0.97 |

| Age | Gender | Education | Contact Quality | Contact Quantity | Affinity | Legacy Motivation | Social Desirability | Social-Altruistic Values | Biospheric Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.02 | - | ||||||||

| Education | 0.08 | −0.10 * | - | |||||||

| Contact Quality | 0.13 * | 0.16 ** | 0.00 | - | ||||||

| Contact Quantity | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.61 ** | - | |||||

| Affinity | 0.02 | 0.18 ** | −0.06 | 0.65 ** | 0.53 ** | - | ||||

| Legacy Motivation | 0.05 | 0.16 ** | 0.04 | 0.38 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.54 ** | - | |||

| Social Desirability | 0.12 * | 0.10 * | −0.09 | 0.32 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.28 ** | - | ||

| Social-Altruistic Values | 0.02 | 0.10 * | −0.08 | 0.37 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.34 ** | - | |

| Biospheric Values | 0.02 | 0.14 ** | −0.05 | 0.33 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.66 ** | - |

| Climate Protection Intentions and Behavior | 0.07 | 0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.27 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.44 ** |

| Scale Range | M | SD | ω | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Quantity | 1 to 5 | 3.15 | 1.11 | / |

| Contact Quality | 1 to 5 | 4.05 | 0.91 | / |

| Perspective Taking | 1 to 5 | 3.70 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| Perceived Oneness | 1 to 5 | 3.13 | 0.95 | 0.76 + |

| Empathic Concern | 1 to 5 | 3.60 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| Climate Protection Intention | 1 to 5 | 2.81 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| Social Desirability | 1 to 5 | 2.77 | 0.43 | 0.60 |

| Social-Altruistic Values | −1 to 7 | 6.02 | 0.95 | 0.78 |

| Biospheric Values | −1 to 7 | 5.55 | 1.19 | 0.85 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Condition (1) | - | ||||||||||||

| Age (2) | 0.08 | - | |||||||||||

| Gender (3) | 0.05 | −0.03 | - | ||||||||||

| Education (4) | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.02 | - | |||||||||

| Contact Quality (5) | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.15 ** | 0.03 | - | ||||||||

| Contact Quantity (6) | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.12 * | 0.11 | 0.46 ** | - | |||||||

| Affinity (7) | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.21 ** | 0.04 | 0.61 ** | 0.50 ** | - | ||||||

| Perspective Taking (8) | −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.21 ** | 0.00 | 0.51 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.84 ** | - | |||||

| Empathic Concern (9) | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.18 ** | 0.06 | 0.59 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.92 ** | 0.65 ** | - | ||||

| Perceived Oneness (10) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.13 * | 0.00 | 0.44 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.75 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.58 ** | - | |||

| Social Desirability (11) | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.16 ** | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.14 * | 0.10 | 0.13 * | 0.12 * | - | ||

| Social-Altruistic Values (12) | 0.03 | 0.14 * | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.31 ** | 0.09 | 0.41 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.14 * | - | |

| Biospheric Values (13) | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.16 ** | 0.00 | 0.14 * | −0.01 | 0.30 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.04 | 0.65 ** | - |

| Climate Protection I. (14) | 0.15 ** | 0.09 | 0.12 * | 0.11 | 0.15 * | 0.16 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.04 | 0.32 ** | 0.47 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Paula Sieverding, T.; Kulcar, V.; Schmidt, K. Act like There Is a Tomorrow—Contact and Affinity with Younger People and Legacy Motivation as Predictors of Climate Protection among Older People. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041477

de Paula Sieverding T, Kulcar V, Schmidt K. Act like There Is a Tomorrow—Contact and Affinity with Younger People and Legacy Motivation as Predictors of Climate Protection among Older People. Sustainability. 2024; 16(4):1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041477

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Paula Sieverding, Theresa, Vanessa Kulcar, and Karolin Schmidt. 2024. "Act like There Is a Tomorrow—Contact and Affinity with Younger People and Legacy Motivation as Predictors of Climate Protection among Older People" Sustainability 16, no. 4: 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041477

APA Stylede Paula Sieverding, T., Kulcar, V., & Schmidt, K. (2024). Act like There Is a Tomorrow—Contact and Affinity with Younger People and Legacy Motivation as Predictors of Climate Protection among Older People. Sustainability, 16(4), 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041477