1. Introduction

Within the wider topic of urban sustainability, this research proposes a methodology to identify intervention criteria for regenerating urban public space. Within the framework of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Goal no. 11 “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” [

1] strives to foster urban development by employing participatory, integrated and sustainable settlement planning. It also focuses on providing access to safe, inclusive and adaptive public spaces.

The research roots in the concepts of urban proximity, urban regeneration and citizen participation in decision-making processes. The concept of proximity service, i.e., offering services and facilities that are reachable on foot and are suitable to diverse demographic groups, has been extensively investigated in literature [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In particular, the concept of the 15-min city, even if well rooted in urban planning discipline fundamentals [

9,

10,

11,

12], has recently gained significant diffusion, both in research [

13,

14] and practical implementation by major European cities (e.g., Paris and Milan). This city planning model, illustrated by Carlos Moreno in 2016 [

15], assumes that residents should easily reach essential urban functions (living, work, commerce, health, education and entertainment) within a 15-min walking or cycling distance from their place of residence [

15,

16].

Moreover, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of various transportation modes has experienced significant changes, with the encouragement of sharing mobility, Mobility as a Service (MaaS) and infrastructures supporting cycling [

17,

18]. Sustainable transport modes should also be enhanced to reduce air pollution and mitigate climate change effects.

In this framework, urban regeneration processes represent an opportunity to pursue a sustainable city model and redesign public spaces and mobility infrastructures (see, among others, [

19,

20,

21]). Urban regeneration is based on principles of urban redevelopment, liveability of public and built spaces and sustainability. Thus, the dialogue with the local community emerges as a crucial issue within the decision-making process [

22,

23]. Public participation, in this sense, becomes a governance instrument for planning interventions pursuing the public interest. This principle of transparency and involvement of citizenship may be promoted by public administrations, allowing and simplifying the exploration of different solutions, in collaboration with various public and private stakeholders [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

This paper thus adopts a dual parallel approach: spatial analysis, through the construction of a GIS database, and collection of citizens’ perceptions, through a public survey, to implement punctual regeneration interventions at different scales in the public open space. The sustainable parameters adopted to improve the inclusivity, safety, resilience and sustainability of cities were tested in Parma, a city in Northern Italy.

The city of Parma, chosen as a case study among others to test the methodology, is an average city in the Emilia–Romagna region. In fact, medium-sized cities represent a significant reality in the European and Italian context and are configured as places of widespread territorial protection. Compared to the rest of the world, European countries, have, for historical and geographical reasons, a higher percentage of their population in small and medium-sized cities, with lower densities than in Asian cities, but much higher than in US cities [

30]. The Italian situation echoes and further highlights the role and importance of medium-sized cities as nodes of development and territorial protection: 20% of Italian citizens reside in medium-sized urban areas with populations between 200,000 and 500,000 inhabitants, and a further 19% in small urban areas, with populations between 50,000 and 200,000, based on 2014 data [

31]. This is why they are suitable for regeneration and redevelopment. At the same time, they do not have the necessary size to autonomously activate those processes of gathering resources for the huge long-term investments needed for transformations.

Medium-sized cities in the European context have also been the subject of numerous funds in the last decade [among others, [

32,

33]. In this context, the choice fell on Parma because the Emilia Romagna Region adopted Law no. 24 in 2017 [

34], which highlights the need for urban regeneration, and therefore the city is located in an innovative context at the Italian level. In addition, the neighbourhood undergoing the testing of the methodology has already been the subject of study; in fact, the paper is part of a larger framework of research carried out in San Leonardo district [

35,

36].

The selection of Parma as a case study was facilitated by the multidisciplinary initiative “ARCHers FOR PARMA”, which aims for urban and sustainable regeneration in a medium-sized city, striving to pinpoint a local case study. Furthermore, the Urbact project called “Thriving Streets”, led by Parma municipality, aimed to enhance sustainable mobility in urban regions from both economic and social standpoints [

37]. The project aimed at activating local policies and foster shared learning and planning processes across ten European cities.

The main contribution of this research resides in its ability to provide an integrated methodology that combines established theoretical approaches with innovative tools for urban analysis and intervention. The innovation of this study consists in the way it combined established urban planning concepts with more recent methodologies. This integration allowed not only to identify priority sites of intervention and design solutions for urban development, but also to assess the ecological impact of proposed interventions. Given the extensive existing literature, our aim is to fill this gap by devising an implementation approach.

The question of research then is: Which criteria identify priority interventions for the regeneration of public space? The main goal of this research is to define an effective methodological framework to determine the most critical urban areas on a neighbourhood scale that need to be regenerated or enhanced through permanent and tactical urban planning interventions. This methodology was adopted because it combines a GIS database with the citizens’ point of view. The study investigates public space by drawing on traditional urban planning literature [

38,

39,

40,

41] to propose innovative approaches to urban regeneration and propose a specific abacus of design solutions according to the outcomes of both technical studies and citizens’ perceptions at the local level.

The public space transformation should bring back to the community attractive social spaces, previously characterised by a sense of insecurity and discomfort, so that everyone can benefit from them. To this purpose, the methodological approach also leads to the identification of factors that contribute to urban insecurity, starting from an analysis of how the city is planned, designed and built.

The document is structured as follows:

Section 2 illustrates the methodological approach, the conducted analyses and the instruments used, while

Section 3 presents the case study of the San Leonardo district in Parma and includes the results of the study, including the spatial and socio-behavioural analyses of the users and inhabitants of the neighbourhood.

Section 4 discusses the examples that corroborate the results obtained, and

Section 5 offers some final reflections and a synthesis of the research.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework (

Figure 1) outlined in this contribution, subsequently tested in the aforementioned case study, was structured in four stages to conduct the research process: (1) defining the GIS database for the technical urban analysis and public space assessment; (2) conducting a public survey through questionnaires to collect citizens’ perceptions; (3) identifying intervention priorities according to a network of public spaces schematised in nodes and axes; and, finally, (4) defining guiding themes and locational criteria for planning interventions of public space regeneration or enhancement.

References, methodologies and diagrams played a key role in defining a logical and coherent methodology. In the analytical phase, the following references were employed.

The economic activities categorisation occurred with the “ATECO” code (ATtività ECOnomiche/Classification of Economic Activities) [

42], an alphanumeric combination that identifies and diversifies the various activities within the urban context. This approach favoured a comprehensive and systematic understanding of economic activities, offering an in-depth perspective on diversification within the urban landscape.

The Biotope Area Factor (BAF) was applied to deepen the surface permeability. It is an index introduced in urban planning tools in 1994 by the city of Berlin, Germany, to enhance the ecological performance of the built environment and to evaluate the ecosystem functionality by quantifying the surface’s absorptive properties [

43].

Inspired by the questionnaire used in the Oltretorrente district in Parma [

7], the San Leonardo survey inherited its main structure and some key components. The adaptation involved exploiting the successful elements and methodologies applied in the previous one to adapt and refine the questionnaire specifically for the San Leonardo context.

In the interpretation phase, the perspectives of Kevin Lynch and Jane Jacobs [

39,

44], provided fundamental conceptual tools. Lynch’s classification of urban elements and Jacobs’ emphasis on securing the city laid a solid theoretical foundation for urban analysis and intervention.

R. R. Singh’s work “Sketching the city: a GIS-based approach” highlights the significance of integrating GIS with Lynch’s method. This approach necessitates conducting a field survey to identify nodes, thereby restricting the study area based on the availability of skilled human labour dedicated to the effort [

45].

In the planning phase, it was useful to use the references and diagrams below. To plan public spaces that are more inclusive and responsive to citizens’ needs, a methodological approach applied in the San Lorenzo district of Rome was used as a methodological reference [

46].

Equally significant was the adoption of the Sankey diagram as a visual and conceptual connection tool as it allowed for a clear representation of the relationships between intervention themes and potential design solutions within the abacus.

2.1. Definition of a GIS Database

The implementation of a GIS database aims to map and spatially analyse all of the main urban components and systems, e.g., mobility, built-up space and open space, morphological, functional and environmental aspects. A comprehensive data model was designed for the urban area studied, to systematise a large amount of information obtained from diverse sources.

The database was populated by acquiring an initial base map from the Spatial Information System of the Municipality of Parma and the Geoplatform of the Emilia–Romagna Region. This base was integrated, through cross-referencing, with the urban data information from previous analyses conducted by the research team. Finally, the informative layers were updated through the photointerpretation of recent satellite images, supported by in-field surveys and photographic documentation.

The database was developed using abstraction levels through a conceptual, logical and physical data modelling process defining, firstly, quantity and content of multiple informative layers and their specific attributes (see

Table 1). Secondly, a series of correlations between informative layers was established to improve and accelerate the updating of attribute data in the different informative layers.

The mapped data’s level of detail is remarkably high, especially regarding the information layers related to public open space, i.e., road area, parking lots, urban green spaces. These layers are constructed to map in detail the permeable and impermeable surfaces, thus associating a specific quantitative index, i.e., the weighting factor useful for the calculation of the Biotope Area Factor (BAF) [

43].

2.2. Preparation of a Public Survey Form

As already mentioned, the structure of the questionnaire for the participatory analysis was inspired by a previous questionnaire conducted in the Oltretorrente district of Parma [

7].

A customised public survey “Public spaces and mobility in the San Leonardo district of Parma” was prepared to collect citizens’ perceptions and opinions on the quality of public spaces, mobility and accessibility. The questions were not compulsory to answer and could be completed by anyone in terms of gender, age and employment status.

The survey includes 21 questions specifically addressed to the resident population and 20 specifically addressed to non-residents and is structured in 8 thematic sections:

Section 1 requests generalities: age, profession and place of residence;

Sections 2 and 3 investigate the most frequented areas in the neighbourhood (both for residents and non-residents);

Sections 4 and 5 analyse mobility issues: most frequently used means of transport, frequency of use of public transport and sustainable means such as cycling (both for residents and non-residents);

Sections 6 and 7 evaluate public spaces, economic activities and public facilities and services: perception of road infrastructure, parking, lighting, green areas and children’s spaces, noise and air pollution, cleaning, stores and activities, schools, offices, health facilities, cultural facilities, facilities for the elderly, sports centres and preferences for redevelopment of public spaces and activities;

Section 8 gathers suggestions for possible future interventions with the aim of improving citizens’ well-being in the interest of the community through an open question.

Thanks to the collaboration with Manifesto San Leonardo, an active local group dedicated to preserving and enhancing the neighbourhood, which had previously submitted surveys to citizens, the questionnaire was distributed within the local community.

2.3. Setting Criteria to Identify Priority Nodes and Axes for Intervention

The determination of intervention priority sites is developed based on a conceptual scheme that conceives public space as a city’s connective element, which is organised according to a networked pattern consisting of nodes and axes [

39,

46]. Nodes are defined as relevant urban centralities where different services or activities coexist attracting people and where different social relations intersect. These nodes exhibit relatively high accessibility that may assume the following main functional characters: business, trade fair and exhibition centres; shopping centres with large-scale distribution facilities; main transport nodes, such as railway stations of the national and regional railway system; hospitals; technological poles, universities and scientific research centres; theme or recreational urban parks; facilities for cultural and sporting events with a high public participation; and relevant neighbourhood cores with a mixture of public facilities and attractive economic/leisure activities, well connected to housing.

Axes are identified as spaces of circulation for the daily mobility practices of citizens, and represent primary connections between nodes. Besides fulfilling this role, they also occasionally act as commercial attractors due to the presence of economic activities, fostering social interaction opportunities.

Priority intervention sites, i.e., priority nodes and axes, are identified by assessing relevant criteria, as defined in

Table 2. These criteria consider both the key issues emerging from the technical spatial analysis through GIS and the results of the public survey.

Spatial analysis helps to determine nodes and axes that share similar characteristics in terms of mobility, functional and environmental aspects. Furthermore, the database can support the downscaling of the Lynch methodology [

39] for assessing nodes, landmarks and paths, defining the urban landscape perception at the neighbourhood scale. The public survey form collects information that helps to locate the most frequented spaces both by the resident and non-resident population.

2.4. Definition of Key Topics to Frame Potential Planning Solutions

To plan appropriate solutions, some key themes have been identified that could lead the redevelopment of spaces. Each theme might include several intervention strategies, as reported in existing literature and experiences (see

Section 1). These strategies are assigned to each intervention site (node or axis) based on a site-specific analysis aimed at assessing criticalities, vocations and potential of transformation and enhancement for each node or axis. Every intervention refers to the urban regeneration and the tactical urban planning sphere.

The themes include functional aspects, accessibility, implementation of sociality, transformation and use of public space, transformation and use of built space and environmental aspects (

Table 3).

The ‘accessibility’ and the ‘implementation of sociality’ recur particularly in several nodes and axes. The improvement of both accessibility and the creation of multicultural spaces concerns public open spaces but also to street areas, which are often used as a social areas rather than simply as moving spaces.

Urban regeneration and tactical urbanism offer effective solutions to the challenges identified. Therefore, the aim is to incorporate some intervention strategies from tactical urbanism to implement them as an integral part of urban regeneration interventions.

However, a radical intervention that envisages a permanent physical transformation of public space may not be the preferred solution of public administrations, firstly, because of the costs implicated, and secondly, because this kind of radical practice has been demonstrated to often cause a first-impact negative response from citizens.

Among urban transformations, ‘tactical urbanism’ is therefore a possible solution to carry out an initial test phase of planning solutions to make local communities gradually adapt to change, and administrations monitor the effects [

47]. Tactical urbanism is a good type of intervention due to its temporariness and flexibility, cost-effectiveness, practicability and scalability. Moreover, it allows community involvement [

48]. Tactical urban planning initiatives (e.g., street re-markings, alternative uses of parking spaces, reconversion of sections of streets and the opening of entire streets to uses other than motorised traffic) aimed at reclaiming street space for public social use, pursuing the vision of “streets for people” instead of “streets for traffic” [

49], are acquiring growing importance precisely for their temporary nature and also promote bottom-up citizen activation. There are numerous interventions in the literature that fall under the concept of tactical urbanism, among which can be highlighted:

The pedestrianisation or semi-pedestrianisation of squares and streets: this involves the closure of private vehicular traffic in certain areas, allowing the passage only to pedestrians, cyclists and, sometimes, public transport or authorised vehicles. It has many benefits for the community because it creates safer, sustainable and more pleasant spaces for citizens, promoting sociality, active mobility and reducing air pollution [

38,

50];

School streets and playstreets: like the previous case, they are obtained through the restriction of motorised traffic at certain periods of time, creating a safer, more pleasant and learning-friendly space for students and can be customised to the specific needs of the school and the surrounding community [

51];

Pocket parks: small green spaces that play a vital role in improving the quality of life of residents and contribute to a more sustainable and lively urban landscape [

52];

Parklets: spaces reclaimed from street parking, either temporary or permanent. Their design and implementation often involve the participation of the local community to ensure that they meet the needs and preferences of residents. Their installation may require authorisation from local authorities, as they involve the conversion of one or more public parking spaces [

49].

Moreover, experiences such as those presented above can also be depaving occasions, i.e., the removal of impermeable surfaces, such as asphalt and concrete, to restore permeability and vegetation cover, promoting biodiversity, urban drainage and reducing the heat island effect [

53]. This has characteristics of co-design and participation, but it is not a temporary intervention.

Tactical urbanism projects have received much interest in the literature in recent years, especially in the way they relate to planning techniques [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59] highlighting its positive aspects, such as public participation, dedicated use of space for people and improvement of slow mobility [

60,

61], but also sometimes failing [

62,

63].

In this context, the question is whether it is possible to regenerate a neighbourhood starting with temporary interventions involving public spaces. To do this, the goal is the identification of mechanisms and criteria that define prioritisation of intervention.

3. Results of the Analysis

3.1. Case Study: San Leonardo District in Parma (Italy)

The municipality of Parma covers an area of 260.6 km

2 and is inhabited by 197,293 citizens, according to 2023 data. It is localised in the Emilia–Romagna Region of northern Italy (

Figure 2a) and stands as an example of a medium-sized city that has experienced rapid urbanisation from the post World War II period onwards. The San Leonardo district covers approximately 4 km

2 and is populated by 20,349 inhabitants (data as of 2020). The foreign resident population represents 25% of residents in the neighbourhood, and 15.5% of all foreign residents in the municipality [

64,

65]. The district is predominantly inhabited by adults aged 45 to 74 (almost 50%), and most people of working age are employed. It is situated in the consolidated suburbs next to the city centre.

The study area does not coincide with the administrative district boundary but consists of an urban portion bounded by the railway line to the south and to the east, by the ring road to the north and the Parma stream to the west (

Figure 2b) and is most prone to socially and physically critical issues.

This area is characterised by a largely residential fabric, but with well-defined productive character due to its origin. In fact, it arose soon after the development of the train station and the first railway line (mid-19th century), indicating its favourability for the establishment of new industrial activities. However, the completion of the railway lines also created a kind of barrier separating it from the city centre, resulting in discontinuity.

During the last ten years, a considerable morphological and identity transformation has occurred. The dismantling or demolition of old production sites produced few large brownfields and numerous small vacant lots scattered throughout. These voids left in the continuous residential fabric have produced a progressive degradation of the built environment, affecting the connected public space and disfiguring the image of the neighbourhood. The lack of control over urban space, caused by the widespread divestment of businesses and abandonment of urban areas, has also led to an increase in micro-crime phenomena over time. At the same time, the progressive obsolescence of the residential building stock, mostly built between the 1940s and 1970s (or earlier), has caused a process of filtering down, favouring the settlement of a share of the less affluent and immigrant population. This scenario has generated a climate of uncertainty and an increase in the perception of social insecurity, which is reflected in the degree of dissatisfaction of the still settled historical local community that nevertheless demonstrates considerable rootedness and attachment to the neighbourhood’s public spaces.

3.2. Results of the Spatial Analysis with GIS

Numerous analyses, conducted within a GIS environment, enabled the development of the subsequent research phases. These include the study of the road and mobility system, land use and the associated property and accessibility.

Some analytical processing carried out using the QGIS 3.28.4 software is shown below.

The land use in the district is mainly residential (

Figure 3), with some large urban green areas, although the presence of extensive industrial areas and disused sites is also conspicuous. This has repercussions on the accessibility of urban spaces that are predominantly inaccessible to the citizens, except for residential land made accessible by the presence of ground floor commercial activities.

Considering mobility issues, the San Leonardo district enjoys good connectivity to the historic centre and the ring road (

Figure 4) through its access roads. These cut through a very extensive 30 km/h zone. The railway station and an urban and suburban public transport hub are concentrated in the southern portion of the district. Various cycling lanes located along the main roads encourage slow mobility but are not constantly protected or in reserved lanes. Although pedestrian mobility is typically ensured, pavements may not always be easily practicable and accessible.

In addition, this software also provided an in-depth study of issues such as access, types and opening hours of economic activities and facilities, soil permeability, urban greenery and heat islands.

Mapping of the concentration activities and facilities (

Figure 5) was achieved through the numerical counting of accesses to economic activities. The ATECO code [

42] allowed us to catalogue the different types of the activities, most of which are related to retail trade, travel agencies, leisure and recreation activities and services. Public facilities are varied and evenly distributed throughout the district, although sports facilities are lacking and facilities in the south-western portion are scarcer.

It can also be observed that there is a good concentration of economic activities and facilities, particularly along four main roads across the neighbourhood.

The deterioration analysis of the built environment shows that the school facilities and the green areas (

Figure 6) in their surroundings are in an obvious state of degradation, exacerbated by the numerous scattered disused lots and the condition of the buildings and of the road surface, both of which are in a mediocre and extremely low state of maintenance.

Following Jane Jacobs’ concept of “eyes on the street” [

44],

Figure 7 also provides a critical overview on the concentration of economic activities and facilities of public interest and the safe presidium they collectively provide during evening and night hours, compared to the real geolocation of micro-crime events. The concept of ‘presidium’ in this context refers to the constant and active presence of economic activities and facilities that act as a point of reference and passage. It is noted that this safe presidium does not necessarily discourage the establishment of micro-criminal activities, but it can have an impact on citizens’ perception because it makes the passers-by feel safer.

Lynch’s study [

39] of the city elements, applied to this neighbourhood (

Figure 8), shows elements such as paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks, both primary and secondary. This approach permitted us to identify that the district is enclosed by edges, which makes it isolated from the rest of Parma. Moreover, there are numerous nodes and landmarks that facilitate the mental schematisation of the space for the residents and neighbourhood users.

3.3. Public Survey Results

A total of 192 citizens participated in the public survey, delivered from 18 May 2023 to 24 July 2023. The varying number of responses for each question was due to their non-mandatory nature. The questionnaire enriched the vision of the neighbourhood with new insights and considerations from the residents first hand, making it possible to clearly identify areas with the highest potential of transformation for regeneration interventions.

Most of the participants (75.9%) are residents in San Leonardo neighbourhood (which means a total of 0.7% of the neighbourhood residents), while the remaining part frequents the neighbourhood for work or other activities. The questionnaire did not make any distinction in terms of age or employment field, and therefore a wide variety of responses were received from students, employees, freelancers and retirees.

The public survey highlighted aspects such as the most interesting sites for the citizens. Furthermore, the most congested times for work, sports or leisure activities are from 16:00 h to 19:00 h.

The crucial issues that emerged from the questionnaire include poor surveillance, resulting in micro-crime, the presence of architectural barriers, neglected public places, poor hygiene and insufficient children’s playgrounds. This increases the sense of insecurity.

Most people visit public spaces six or seven days a week for work or because they live nearby, but few visit the area for other reasons.

Most people move around the neighbourhood on foot or by bicycle daily (62.0%), but a greater extension of bicycle lanes and their regular maintenance could improve travel and encourage more people to cycle because almost all destinations can be reached within 15 minutes. Public transportation is underutilised due to inefficient routes.

The participants highlighted the main former industrial site as an area requiring regeneration and requalification, suggesting the implementation of services such as libraries, parks and a sports centre. They would also appreciate a cultural centre, a theatre and a cinema. This suggests a need for cultural aggregation activities. Other suggestions include measures to improve safety and hygiene, an increase in green spaces equipped for children, elderly and people with disabilities, and a better connection between the neighbourhood and the city centre.

As depicted in

Figure 9, the questionnaire participants were asked to express which sites they frequent or visit the most, and the north-western sector is the most voted.

Figure 10 summarises the participants’ considerations on various aspects (condition of roads and pavements, quality of bus stops, parks and children’s spaces, accessibility, parking and public lighting). Good and excellent marks are very scarce, which demonstrates a degree of dissatisfaction due to the low quality of public space and urban organisation in the neighbourhood.

3.4. Selection of Priority Nodes and Axes

As explained in the identification of potential intervention sites, ten nodes and ten axes were identified (

Figure 11) using selective criteria and feedback obtained through the public survey. The results therefore identify the attractive nodes, highlighting their potential and their criticalities.

Table 4 identifies each node with the district location and the description of the economic activities and facilities in the public spaces.

The public spaces selected as preferred by the questionnaire results are located in nodes N1, N4 and N7.

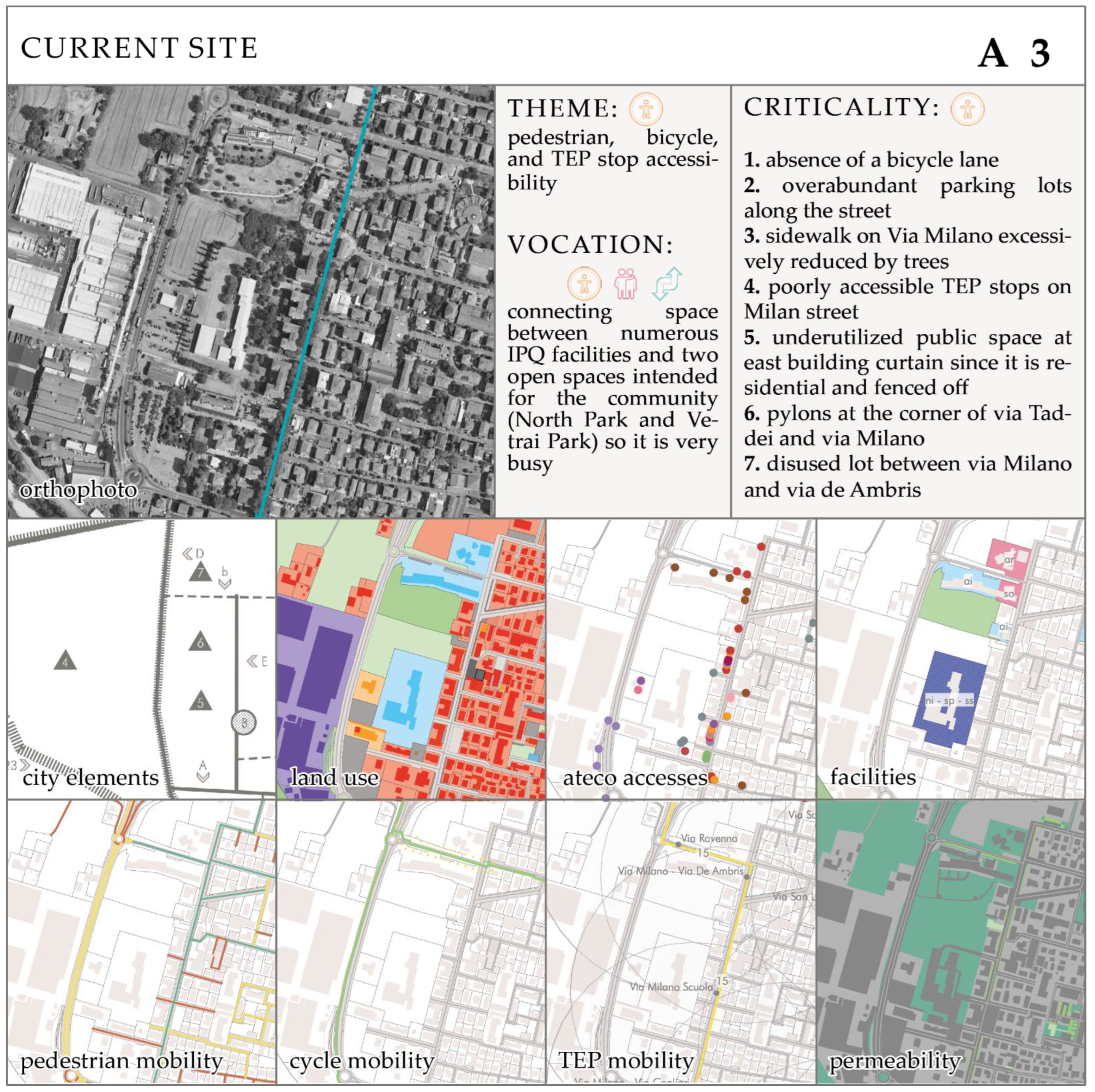

To connect the ten nodes, ten axes were evaluated, classifying them by type according to their intrinsic characteristics. Regarding the choice of axes, citizens expressed a preference for axes A3 (Via Milano), A5 (Via San Leonardo), A6 (Via Trento) and A8 (Via Venezia) through the questionnaire. This facilitated the selection process.

Four of the ten selected axes were chosen according to criterion 1, i.e., the presence of commercial activities. Commercial axes were defined counting the multiple economic activities linked to section G of the national ATECO [

42] classification, i.e., commercial sector. The selection includes axes A5 (Via San Leonardo), A6 (Via Trento), A8 (Via Venezia) and A10 (Via Trieste). These axes are characterised by the presence of commercial activities related to retail trade.

The selection of the other axes, i.e., the connecting axes, is linked to the mainly private road mobility system, the permitted speed limits (almost always above 30 km/h) and the amount of traffic they support. The connecting axes found include A1 (Viale Europa); A2, i.e., the connecting axis formed by Via Ravenna and its continuation Via Camillo Prampolini; A3 (Via Milano); A4 (Via Cagliari); A7, identified with Via Paradigna; and finally A9 (Via Palermo). The presence of businesses is not the fundamental prerogative of these routes, which, rather, have only sparse economic activities.

3.5. Identification of Planning Strategies and Solutions

In the next phase, the analysis on priority sites was deepened. Regarding the axes, the key themes of accessibility and environment (as identified in

Section 3.4) were further assessed.

To evaluate accessibility, travel time from one node to another was calculated for each axis, considering various modes of transport (

Figure 12), i.e., on foot and by bike, car or public transport. In addition, an assessment was made to determine if the axis formed part of a green corridor, contributing to ecological continuity. This aspect also contributes to the pleasantness of travel, especially for pedestrians and cyclists. The green infrastructure includes part of A1 from the junction with A4 to the southern end of the road, part of A2 along Via Ravenna and Via Camillo Prampolini and axes A3 and A6 in their entire extension.

As a result, it emerged that green connections are scarce, affecting the psychophysical well-being of road users, so that vegetation could be implemented along all axes. Additionally, accessibility to public transport should be increased on longer streets, where the walking distance exceed ten minutes.

Concerning the nodes, a specific study on criticalities and vocations was conducted to formulate a planning strategy for the redevelopment and enhancement of public space. The critical issues identify the potential for regeneration and tactical urbanism interventions to be improved, while vocations were determined using each node’s distinctive features such as economic and social elements.

Figure 13 shows the outcome of this in-depth analysis and the identification of the key themes associated with the planning strategy for each node.

The planning strategy shows that the range of themes from N1 to N10 is remarkably diverse. However, the essential challenges are mostly related to the transformation and use of public space, as it is considered underused or degraded, and the vocations are very often socially oriented. In N1 and N8, issues and vocations are interconnected as both related to sociality.

In general, transformation and use of public space and the implementation of sociality are the most frequently occurring themes, while intervention involving new functions and the transformation and use of the built environment are localised.

Through the support of a Sankey diagram (

Figure 14), the intervention themes (functional aspects, accessibility, implementation of sociality, transformation and use of public space, transformation and use of built space and environmental aspects) are addressed in an abacus of design solutions. Each of them may also respond to more than one theme, demonstrating a variety of potential solutions through urban regeneration and tactical urbanism intervention.

The variety of potential solutions highlights the difficulty of the process but positively contributes to the richness and feasibility of the planning strategy.

Two possibilities were considered: a permanent type of intervention, e.g., the drastic reduction of roadside parking, which is difficult and problematic, and a tactical urbanism type of intervention. The latter is preferable, temporary, lower-cost, removable and aligns with the majority of selected planning solutions for nodes and axes.

Urban regeneration and tactical urban planning interventions contribute to the growth of the multicultural identity of the neighbourhood. This occurs through participatory planning and design, improving public and built space.

The issue of accessibility can be solved through the inclusion of bus stops, the reduction of parking lots, the pedestrianisation of streets and squares, shared mobility services and environmental aspects through paving and greening.

Subsequently, the suitability of the site-specific methodology was verified by determining to which nodes and axes the abacus design solutions were applicable.

The study revealed that nodes N1, N2, N4, N7, N10 and axes A3, A4, A8, A9 show a plurality of feasible design solutions for each theme. Particularly, those related to accessibility and sociality are by far predominant.

4. Discussion of the Results

The section discusses the results by interpreting which of the ten nodes and ten axes were most urgent based on findings investigated through the academic study and the questionnaire.

Neighbourhood residents and users expressed their opinions through the questionnaire, showing that the area where they spend the most time is the North-western sector (

Figure 9). In this sector, nodes N1 and N2 and axes A1–A5 are localised. This is particularly important because the will of the citizens must be respected since they are the ones who experience spaces. Therefore, it is of some urgency to begin regenerating the places they frequent most.

Analytical studies, on the other hand, showed that node N1 is the most representative of the neighbourhood because it offers a multitude of diverse economic activities, facilities and public spaces.

In addition, a strong relationship between node N1 and axis A3 should be noted. In fact, axis A3 of Via Milano is directly connected to node N1 as it is the tangent route that provide access to the public facilities and urban park of the node. Moreover, it allows connection of squares, economic activities and facilities of public interest arranged along its length.

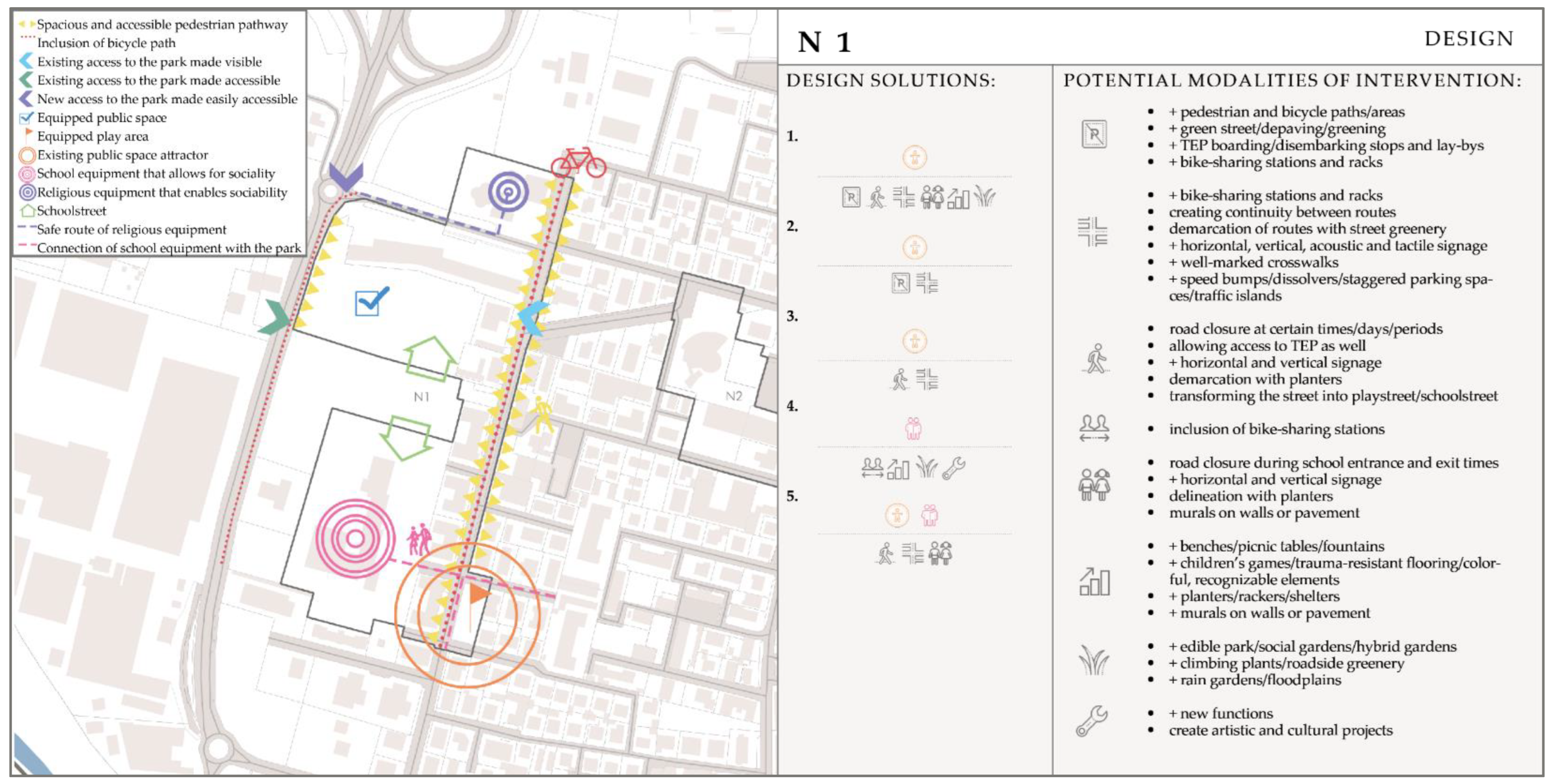

Therefore, among the identified nodes and axes, the selected cases include node N1 and axis A3, which provide an example of intervention form.

The form is articulated in two parts: 1) summary of the analyses and assessment of the site’s current state and potential transformation, 2) scheme of the planned interventions.

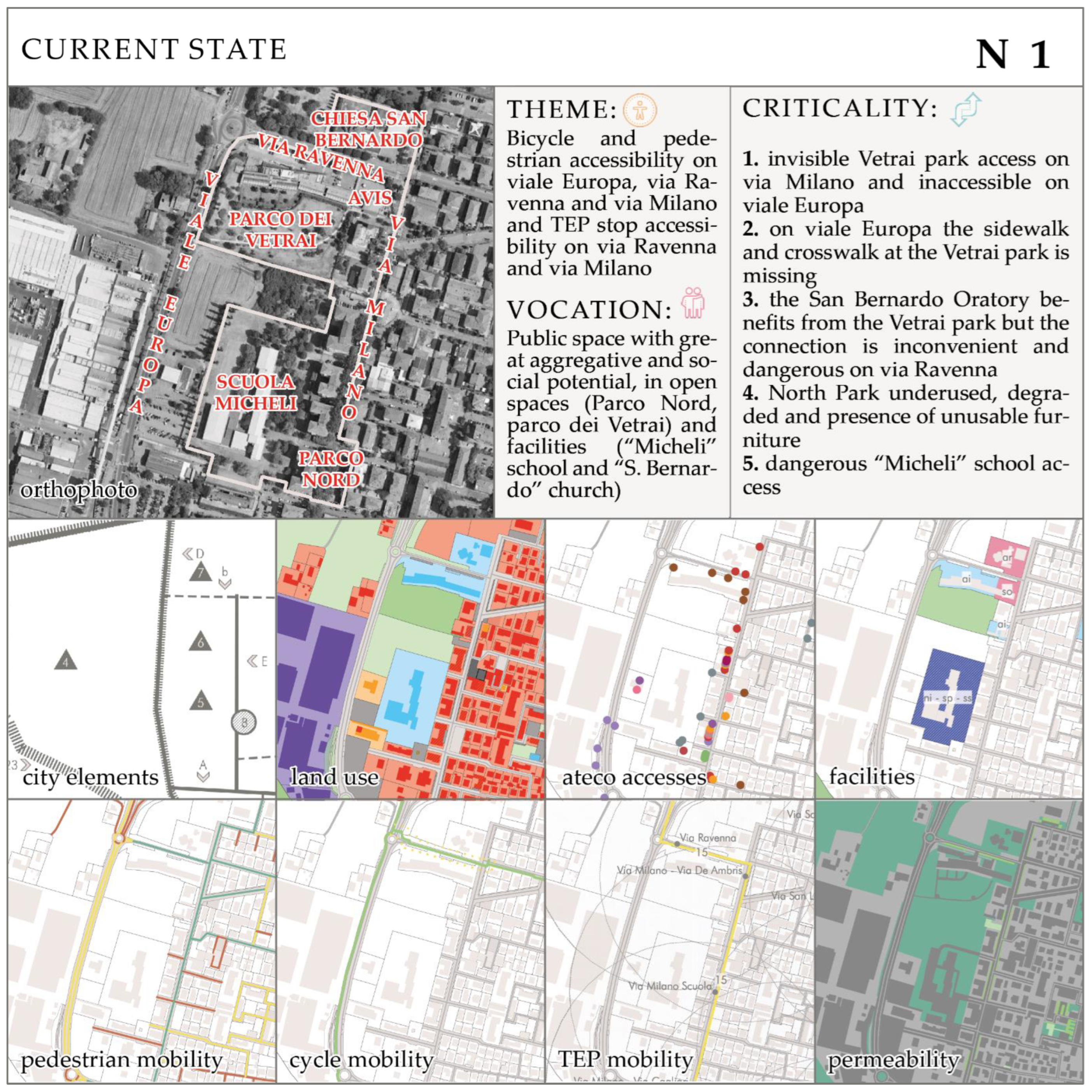

4.1. Node N1 Intervention Form

Node N1 is located in the West of the study area. It emerges as an urban space with significant aggregative and social potential. In fact, it includes open spaces (Parco Nord and Parco dei Vetrai), school and religious facilities (Micheli school and Chiesa San Bernardo), health and sports facilities (AVIS centre), as well as commercial activities facing the road to the east of the district (

Figure 15). Accessibility to public transportation stops is optimal because they are within a maximum walking distance of 300 m.

The primary actions to regenerate and redevelop the public space of the node mainly refer to its walkability and aggregation potential (

Figure 16).

Possible actions and design solutions of the abacus include:

Increase the accessibility to the Parco dei Vetrai enhancing the existing access to the east (on Via Milano), e.g., enlarging the pedestrian path, marking it with vertical signage, highlighting the paving, introducing elements of street furniture and considering the path as an integral part of the park itself through the addition of hybrid gardens, hedges or rain gardens. Moreover, creating suitable conditions to add new access points, e.g., by providing a new cycle and pedestrian path along the high-traffic road to the west (Viale Europa) achievable by converting the roadside verge and rightsizing car lanes that are currently too large; trees and shrubs would also be appropriate to provide shade and reducing environmental and noise pollution.

Improve and make safer the connection between the church (Chiesa San Bernardo) and an urban park (Parco dei Vetrai) by reducing the speed on Via Ravenna through the introduction of chicanes, appropriate signage and by adding green traffic islands.

Qualify the other urban park of the node (Parco Nord) as an intermodal hub, through the inclusion of recharging stations for electric vehicles and a bike-sharing station. To transform it into an attractive node for leisure and recreation, it is necessary to integrate elements of street furniture such as benches and tables, with power sockets, trees, drinking fountains, children’s playgrounds and bicycle racks.

Facilitate the access to the comprehensive institute Micheli which is not safe enough.

4.2. Axis A3 Intervention Form

The axis considered for the project proposal is axis A3 (

Figure 17), tangent to the South-east with node N1 and parallel to the district’s main street (Via San Leonardo). The most important issues concern the clusters of accessibility, sociality and transformation of public space. The most evident critical issues concern accessibility, particularly regarding infrastructures supporting pedestrian mobility.

Potential actions and planning solutions include tactical urbanism interventions, which are characterised by their temporary nature and could test the actions for a limited period. Among them (

Figure 18):

Expand the footpath which is sometimes absent or not wide enough (for example by reducing roadside parking spaces);

Add a bicycle lane by removing parking spaces on one side of the road. Perhaps the solution of semi-pedestrianisation of the street is preferable. This potential includes the establishment of a playstreet/school street (also given the proximity to the Micheli school) in which only bicycles and public transport means are allowed. The temporary pedestrianisation could also have a social purpose by providing a safe environment for children to play and adults to interact and socialise;

Include services to support slow mobility such as bike racks and bike-sharing stations; furthermore, intramodality could be improved in the proximity of public transport stops, e.g., near Parco Nord, including bike-sharing stations or electric charging stations;

Reduce car speed through speed humps and other traffic-calming devices to increase safety for pedestrians;

Make public transport stops more accessible through wheelchair ramps/pedestrian walkways, horizontal, vertical, acoustic and tactile signage, shelters with seating and rest areas, and boarding/landing areas.

This detailed study of a node and an axis is useful to validate the procedure for selecting priority sites, key themes and possible strategic planning solutions for public space redevelopment or enhancement. The definition of detailed design solutions in the abacus necessarily descends from site-specific characters and relations with the urban environment. However, the methodology endeavours, through technical and interpretative analysis developed on a neighbourhood scale, to recognise the public space backbone with specific vocations and criticalities for its nodes and axes, and to prefigure intervention key themes for enhancing accessibility and a rich urban system of social and environmental relations.

This “a priori” recognition simplifies the intervention planning phase in two manners: on the one hand, by allowing the definition of priority sites within the public space network; on the other hand, by helping to select design solutions from the options presented in the abacus, based on delimited key themes.

Moreover, it is validated and better specified through the detailed intervention form. In particular, the form section on the current state verifies criticalities and transformation potentialities of the node/axis; it also checks the node/axis perimeter and the possibility to include or exclude conterminous urban spaces. Meanwhile, the form section with the proposal identifies a series of interventions useful for planning/programming future public works, starting from the previously selected key themes.

The foreseen public interventions may have either a durable nature or even temporary nature to allow a testing phase of the citizens’ response. In this second case, intervention forms could also be useful material for public administrations to support a participatory or co-design process together with local communities.

The methodology could be effectively employed within the city plan in the context of Emilian medium-sized cities, given the strategic nature of the local urban planning tool envisaged by the new urban planning law of the Emilia–Romagna Region (Urban General Plan, i.e., PUG) [

34]. Indeed, the Urban General Plan envisages a general planning framework made of objectives, strategies and actions. The methodology outlined in this work could be easily included within this framework.

5. Conclusions

The paper presented a methodology applied to the case study of the San Leonardo neighbourhood in Parma, identifying priority nodes and axes to be upgraded for improving the accessibility and inclusivity of public space. The proposed approach provides the integration of different levels of investigation aimed at identifying priority areas for intervention within the public space network. The methodological framework consists of four steps and leads to the definition of vocation and criticalities of priority nodes and axes, selecting key themes that guide the planning strategy through the identification of suitable actions for the social and environmental regeneration of places. The suitability of the resulting intervention strategy is then verified by investigating two sites, a node and an axis, and planning possible site-specific design solutions.

The study methodology investigates public space through the innovation of traditional analytical approaches (expert and technical knowledge) with public engagement techniques to collect the instances of local communities. This collaboration between the two competences is a positive thing because it facilitates dialogue between two very distant worlds, such as GIS and social life.

The technical interpretation of the questionnaire permits a sociological analysis of the neighbourhood that provides a better understanding of the meaning of productive and multicultural identity. Indeed, the perceptual sphere of users allows urban planners to better identify priority areas for intervention. This encourages the search for nodes and axes that provide quality space for citizens to gather and socialise, enabling them to determine, through the technique of urban expertise, how to intervene in these sites.

Selection criteria guide the choice towards the identification of several potential intervention sites (crucial places for neighbourhood life, aggregation nodes and most critical/vulnerable places), themes and abacus of design solutions. The intervention strategy highlighted in the paper aims primarily at improving accessibility for all by reducing the impact of cars within the public space and enhancing the neighbourhood’s economic activities and public facilities which could provide a natural control over the urban space, especially if characterised by disuse, degradation and consequently by a perception of low security. One suggested way of implementating experimental design solutions is with a temporary approach, e.g., using tactical urbanism. This approach allows public administrations to involve local communities in a participatory transformative and regenerative process and to have an interpretative tool to select the initial sites in need of urban regeneration or tactical urbanism interventions.

The methodology of Lynch (1960) [

39] was chosen because it can help us understand the relationships between the elements and mechanisms that govern public space. This is why it is still very relevant even after 60+ years.

The methodology was only applied to the San Leonardo case study to verify the methodology potentialities and limits, and it was found to be useful and adaptable (site-specific) for this case. To assess the positivity of the research, therefore, a follow-up with other districts should be carried out. This first application approach permits identifying future work perspectives and other case studies. In fact, it can be adopted by urban plans or public policies of medium-sized cities for the construction of strategies to improve urban accessibility and inclusivity.

The research makes it possible to choose on which areas to concentrate efforts, both economically and regeneratively, to achieve a strategic intervention not only for an individual neighbourhood, but for an entire city.

The paper can be considered innovative in its integrated approach to urban planning, in paying specific attention to local needs and in adopting more flexible and participatory solutions.

The methodology approach is discerning and inherently upscaling-oriented; indeed, it can be easily replicated in contexts of suburbs adjacent to historic centres in both medium and large cities. Conversely, it presents some limitations: in fact, it is challenging to adapt in Italian contexts such as historic centres, rural areas and small cities due to their frequent inaccessibility and unsuitability for urban transformations.

Another limitation of the methodology may relate to the scale used. Although it seems appropriate to develop the methodological framework at the neighbourhood scale, its possible use in urban planning instruments may require an upscaling to the entire urban area. This extension could complicate some steps, such as the construction of the GIS database, but also the public consultation phase by means of a questionnaire.

In this sense, the question could also be raised as to whether the methodology designed for a medium-sized city can be transferred to larger cities or metropolitan areas. There would be many issues to consider in this upscale phase, including revising the criteria for selecting nodes, imagining considering only polarities with higher-level facilities, but also techniques for public engagement and bottom-up involvement.

The possible integration with plans at the local level in the Emilian context was stated in

Section 5, and an application in the strategic planning tools of other medium-sized cities seem possible. In fact, European medium-sized cities share some common urban issues, as well as being a rather characteristic case for Italy due to their abundance. Nevertheless, the abacus of proposed design solutions cannot be applied blindly but must consider the specificity of the different urban contexts and sites. The case of possible applicability in large or metropolitan cities is different, and the methodology in this case would need revision and refinement. This is certainly a topic to be explored in future work to make the methodology easily scalable.