My Human Rights Smart City: Improving Human Rights Transparency Identification System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Summary of the Methodological Approach and Choice of Target Audience for the Research Work

- Literature review with the identification of articles using the descriptors “smart city”, “smart and sustainable cities”, “human rights”, “violation of human rights”, and “freedom and justice” in Portuguese and English. The terms were searched in combination, and the abstract analysis considered articles between 2018 and 2024 in the databases Portal de Periódicos da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Ensino Superior (CAPES Brazil) and Scientific Electronic Library Online (Scielo).

- Definition of the target audience for the research through intentional research, namely, managers specializing in management, sustainability, and human rights from the research partner company.

- Definition of the workshop application method, including action research with an exploratory bias through design thinking (DT) to generate insights using storytelling and business model canvas (BMC) techniques.

- Creation of a functional software prototype for demonstration to workshop participants, where collective concepts could be applied and experimented through a responsive website for iOS and Android operating systems.

- Identification of points for improvement and future studies in order to use the first developed version of the software as this governance tool can potentially serve more than 30 countries and 70 million citizens worldwide.

2.2. Design Thinking (DT) and Its Application

- Desire and ability: Does the solution meet a real customer need?

- Technicality: Is it possible to develop a technically viable solution that is better than what is currently available?

- Feasibility: Is there a viable and sustainable business model for this solution?

2.3. About the Research Participants—Design Thinking

2.4. About the Workshop—Design Thinking Session

2.4.1. Design Thinking—Day 1

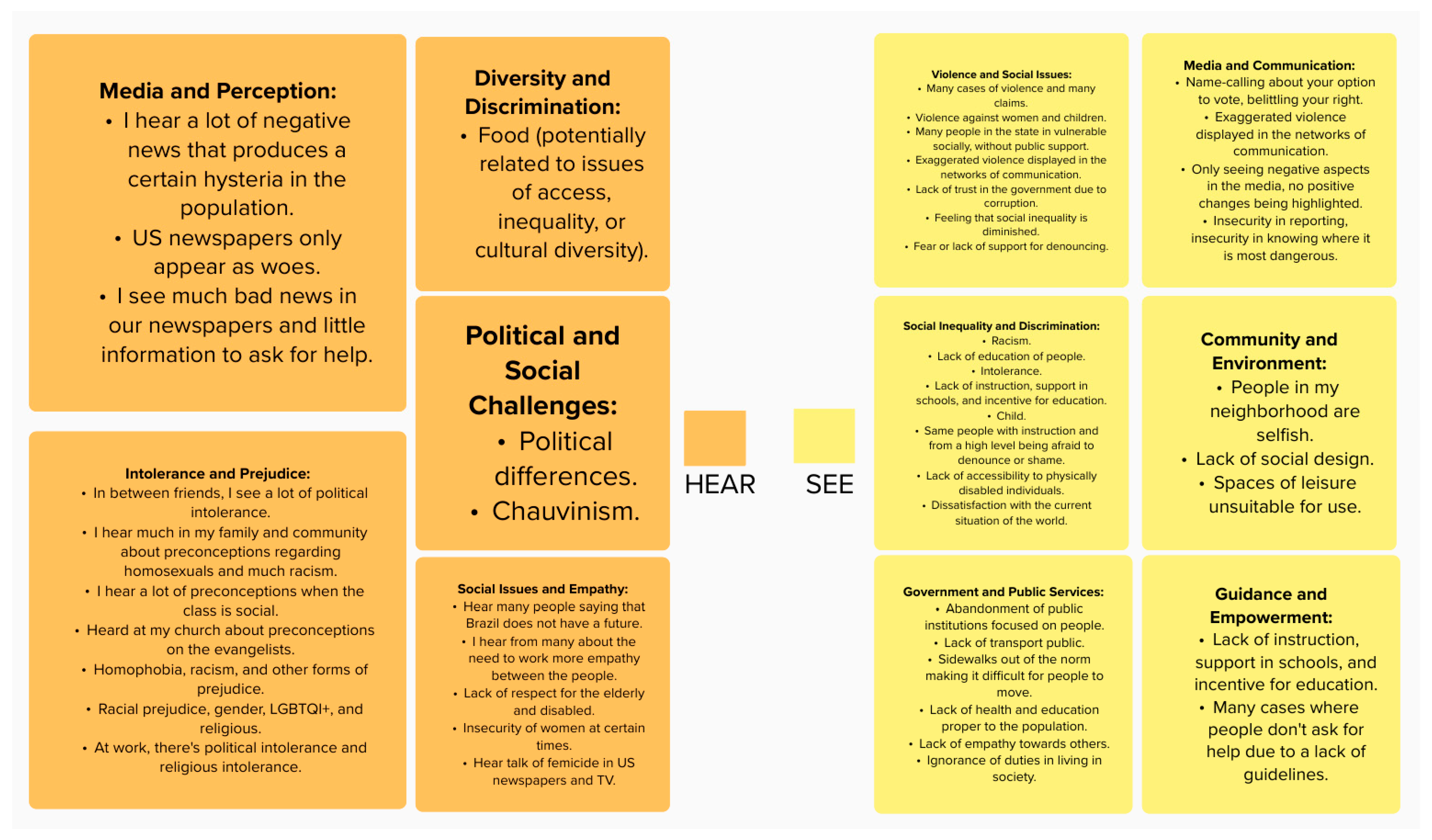

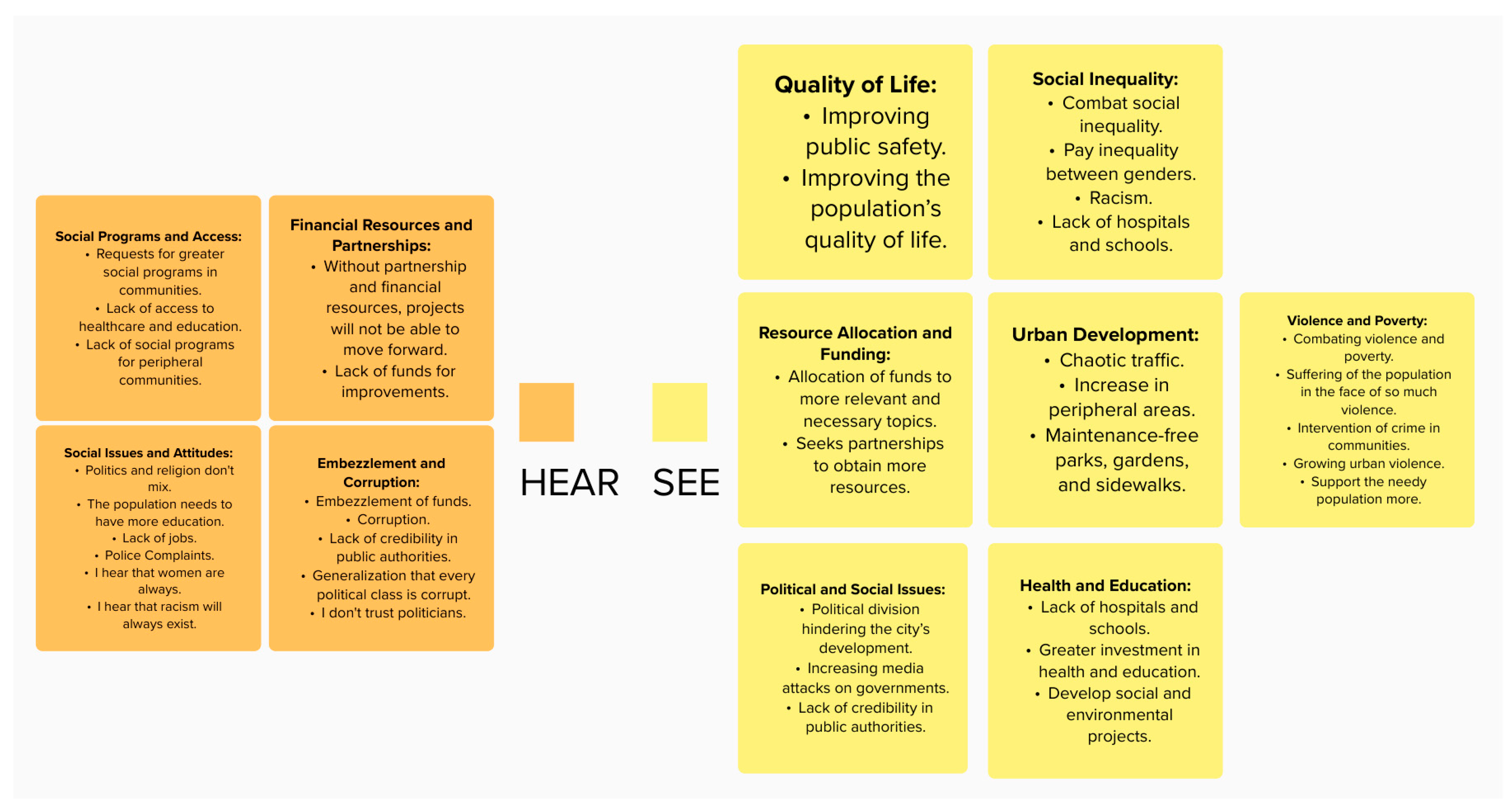

- Context (SEE—what the user sees, observes, and encounters daily; HEAR—what the user hears and impacts their experience). The result is presented in Figure 5.

- Participants express anxiety about violence, inequality, and media negativity. They see widespread violence, exaggerated online content, and distrust in government due to corruption. Social concerns include racism, intolerance, lack of education, and feelings of discrimination on grounds such as class, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. Fear, a lack of support for reporting, and negativity from the media exacerbate these issues. Brazilians also see public spaces as neglected, lacking essential services such as transportation and healthcare. They yearn for better social design, empathy, and guidance to address these challenges.

- 2.

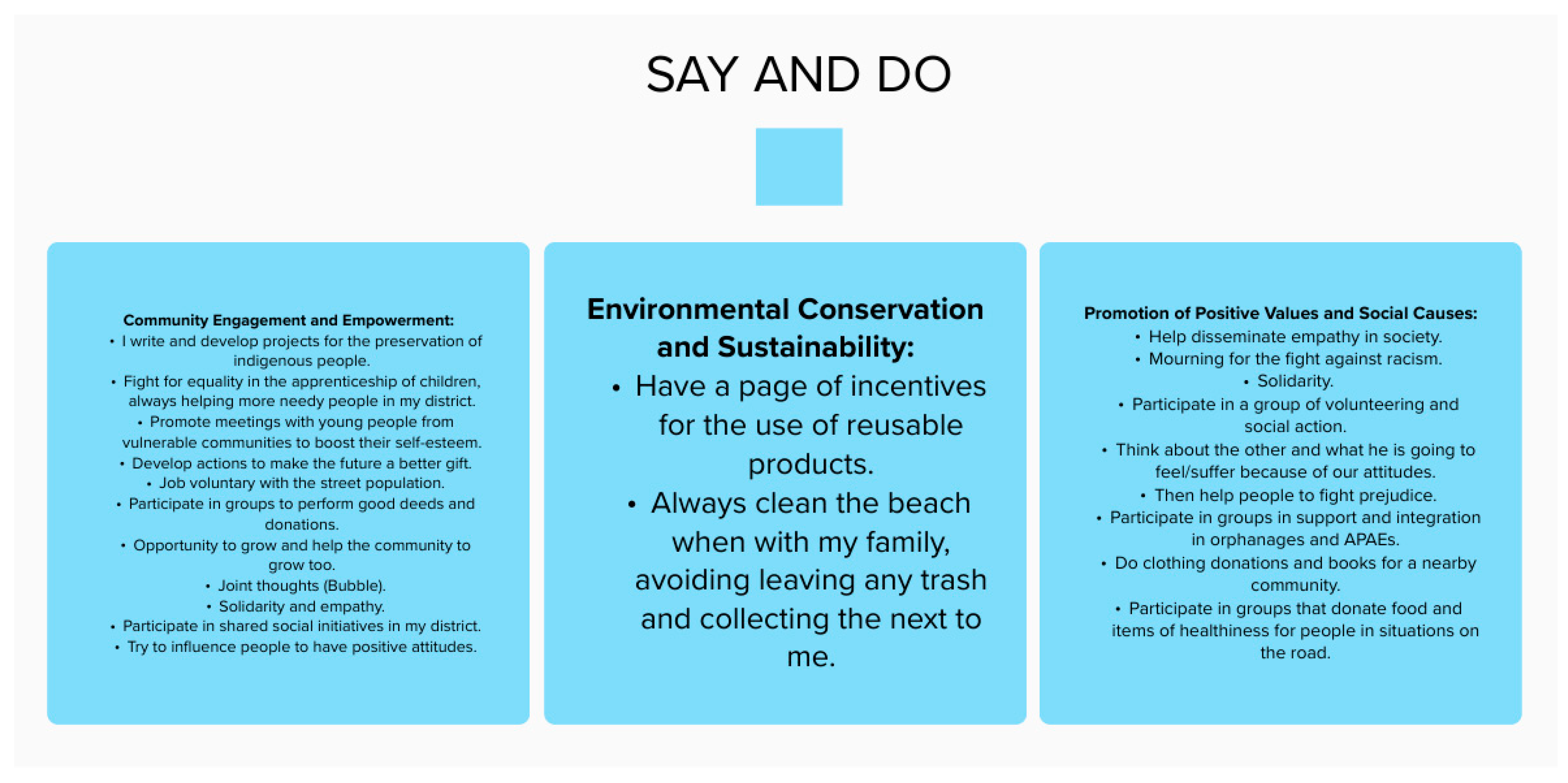

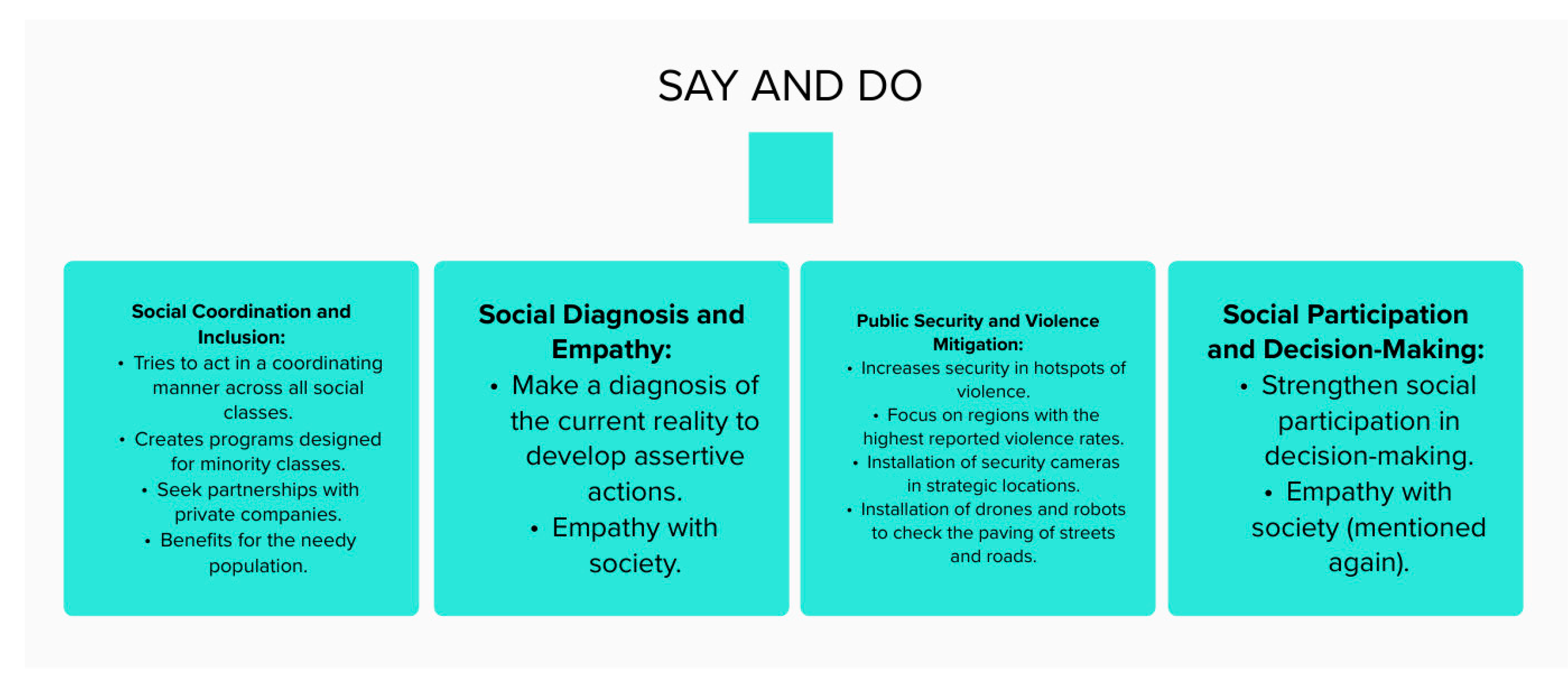

- Actions and expressions (DO—describe what the user does and specific actions and behaviors related to the objective; SAY—write down what the user says, thinks, complains, and comments). The result is presented in Figure 6.

- Participants combine personal action with community support, addressing issues ranging from inequality and youth empowerment to environmental conservation and social compassion. Through texts, projects, beach cleaning, and volunteering, they defend indigenous preservation, fight for fairer childhoods, empower the vulnerable, and defend sustainability. Empathy fuels every step, encouraging others to build a better future through shared initiative, positive influence, and a deep belief in helping individuals and communities grow.

- 3.

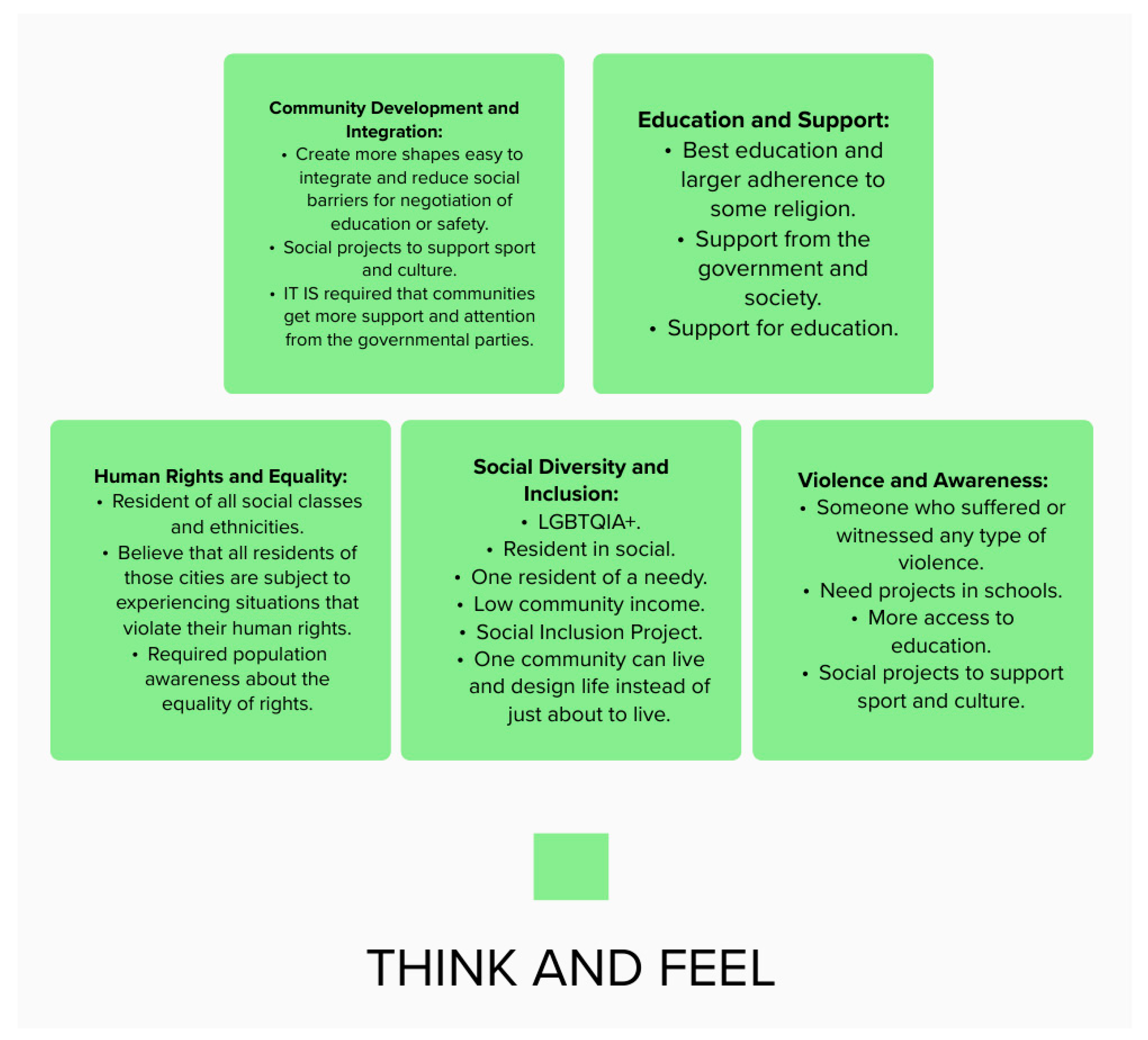

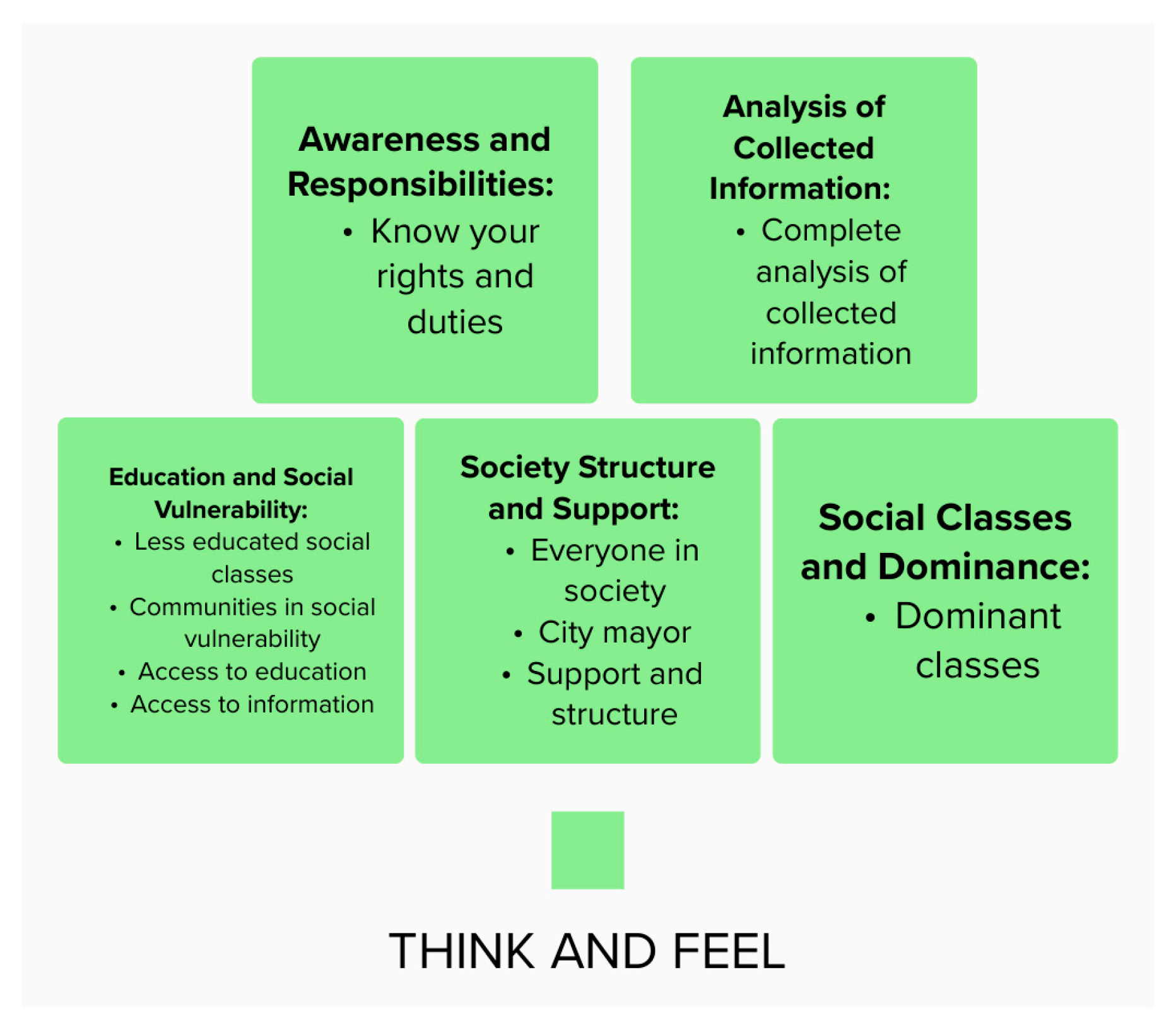

- Motivations and emotions (THINK—explore thoughts and beliefs; FEEL—focus on the user’s emotions and feelings). The result is presented in Figure 7.

- Diverse, woven, tight communities yearn for seamless integration, open education, and safe havens. Sports and culture ignite unity by acknowledging vulnerability and championing equal rights. From government halls to houses of faith, support flourishes for education’s torch. LGBTQIA+ and low-income families all find embrace—empowered to design their lives, not just endure. Education, awareness, and social upliftment combat violence, paving a path to thrive with compassion.

- 4.

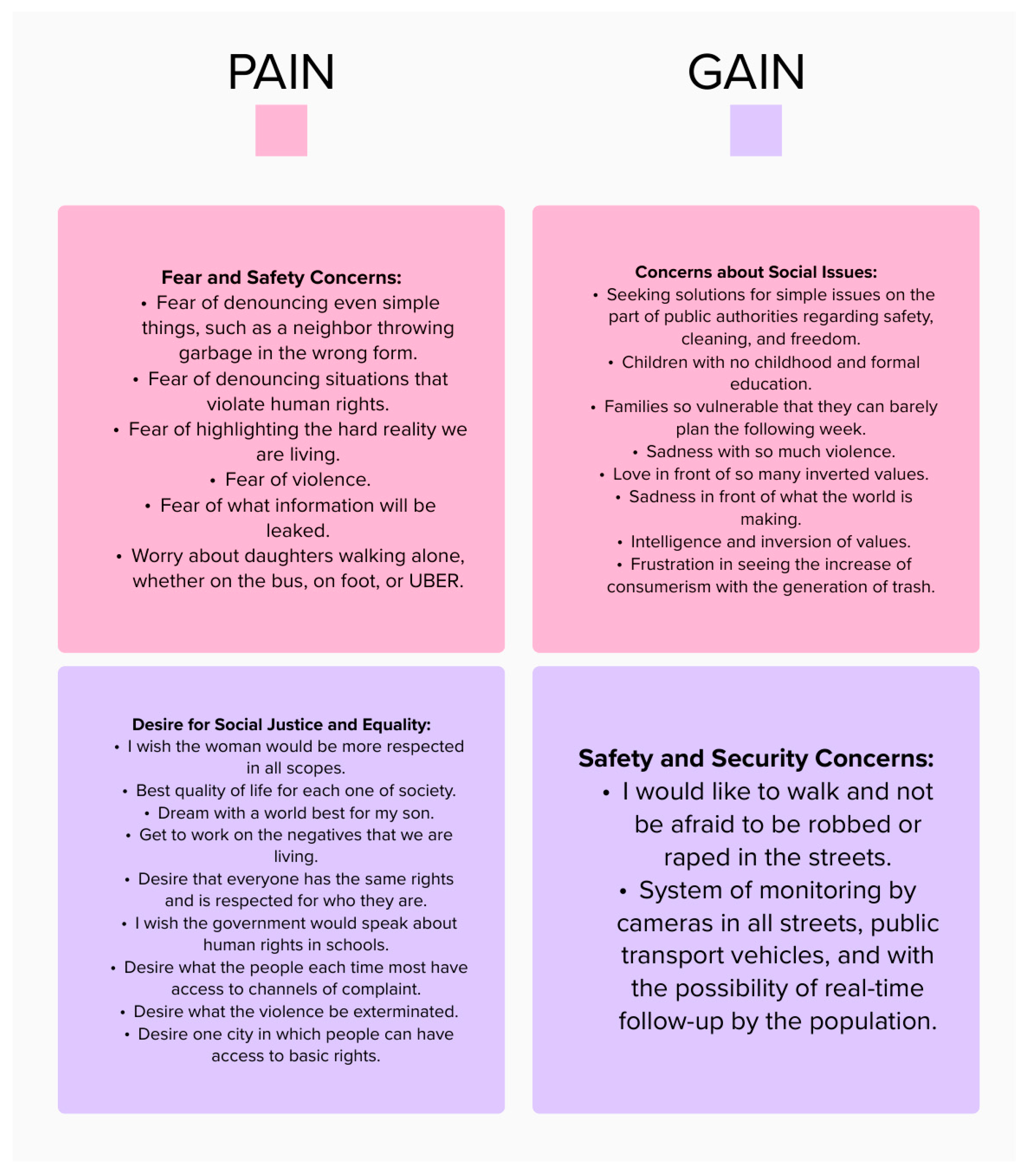

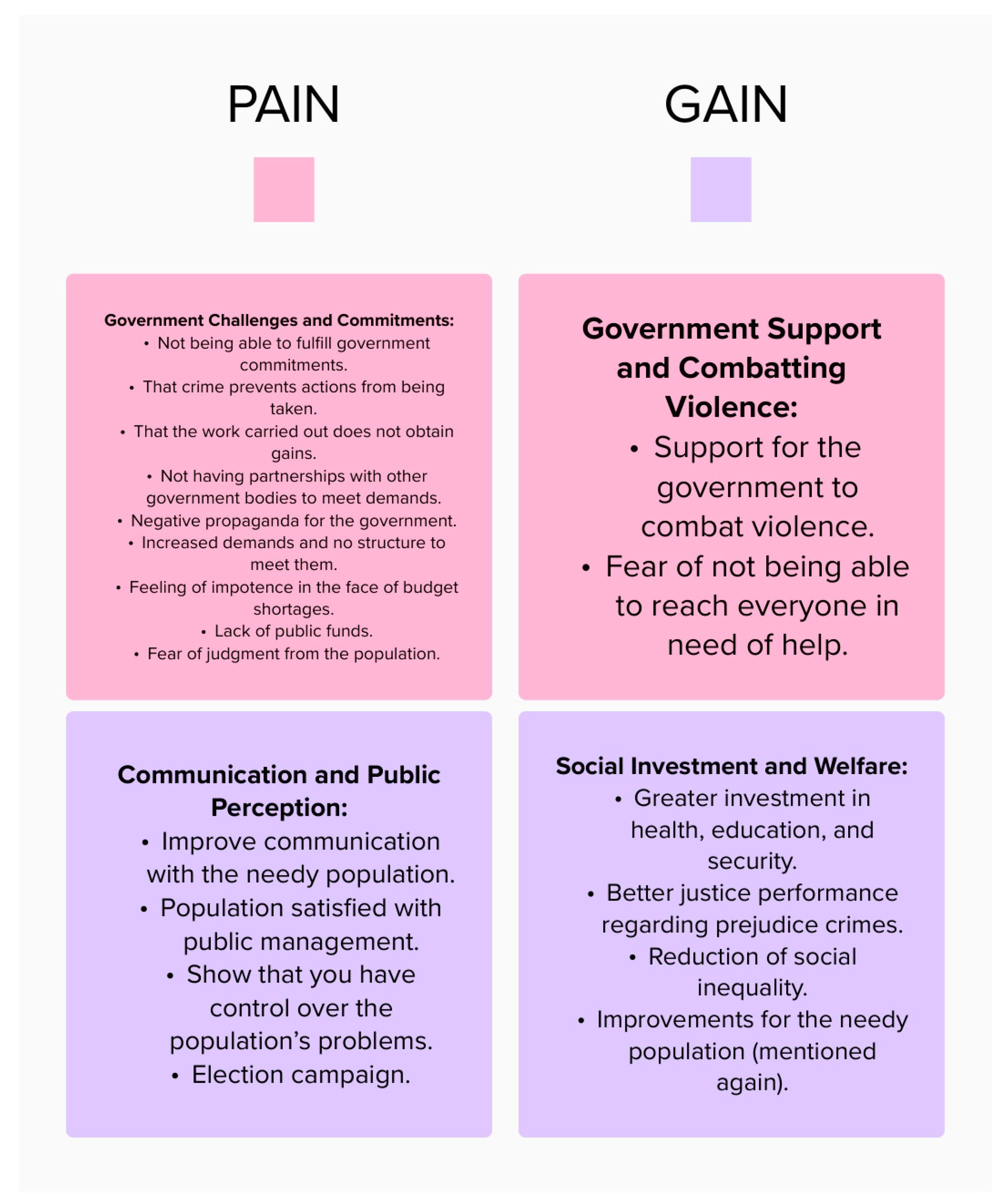

- Pains and Gains (PAIN—represents pain points; GAIN—fulfillment of gains and desires). The result is presented in Figure 8.

- Participants paint a stark picture of societal fears and frustrations, yearning for a fairer and safer world. They fear reprisals for speaking out and witnessing violence and worry about their daughter’s well-being. They see children lacking education, families struggling, and rampant consumerism. Yet, amidst the sadness, glimmers of hope shine through. They aspire for gender equality, a better life for all, and access to fundamental rights. They dream of a world where people are respected, violence is gone, and complaints are heard. Ultimately, the author’s plea is for a city where walking the streets does not evoke fear but a sense of security and belonging.

- What the user sees. The result is presented in Figure 10.

- Users yearn for a city free from violence and poverty, with resources prioritized for areas of need. Political division hinders progress, while crime plagues communities. Media scrutiny intensifies as social inequality widens and chaos engulfs traffic. Violence against women rises, while parks and schools crumble. Public trust wanes amidst infrastructure woes and peripheral expansion. Users crave interventions such as social–environmental projects, robust healthcare and education, and improved public safety, ultimately seeking a better quality of life for all. These diverse anxieties paint a stark picture, demanding solutions across the social spectrum.

- What the user hears. The result is presented in Figure 10.

- The user’s map paints a picture of a community yearning for progress but hindered by a lack of resources and distrust. They see projects stalling due to funding problems, suspect misappropriation of funds, and long for expanded social programs. Access to healthcare and education is limited, particularly in the outlying areas. The mix of politics and religion raises concerns, while a belief in the need for better education resonates. Job scarcity and a perceived lack of improvement funds add to the frustration. Woven throughout is a deep skepticism: corruption is assumed, racism is seen as entrenched, and public authorities lack credibility. This widespread distrust in politicians, often seen as universally corrupt, and reports of police misconduct paint a bleak picture of societal trust. Ultimately, the map reveals a community burdened by negative perceptions and yearning for a more just and equitable world.

- 3.

- What the user thinks and feels. The result is presented in Figure 11.

- The user seems concerned about societal inequalities, particularly regarding access to education and the vulnerability of certain groups. They value inclusivity, recognition of various classes and communities, and access to information and rights. They hope for leadership solutions, individual courage, and thorough analysis to address these issues.

- 4.

- What the user says and does. The result is presented in Figure 12.

- Aiming for action beyond security cameras, this initiative seeks holistic solutions to violence. It fosters social cohesion through empathy, minority-focused programs, and cross-class collaboration. Partnerships with private companies bring resources, while data-driven approaches like street-scanning robots and violence hotspot analysis guide effective solutions. Ultimately, this plan prioritizes the underprivileged and empowers community participation for a safer, more equitable future.

- 5.

- Pains. The result is presented in Figure 13.

- The government wrestles with fulfilling promises, crime-hindering action, and work yielding scant results. Partnerships are scarce; hostile public relations and the fear of neglecting those in need gnaw. Demands surge without resources to match, leaving a feeling of impotence. Support for tackling violence is sought, as is public funding. Judgment by the people haunts them. These anxieties reveal the government’s struggles—execution hurdles, resource deficiencies, external pressures, and fear of public disapproval. These are crucial to understanding public administration’s obstacles and service delivery challenges.

- 6.

- Gains. The result is presented in Figure 13.

2.4.2. Design Thinking—Day 2

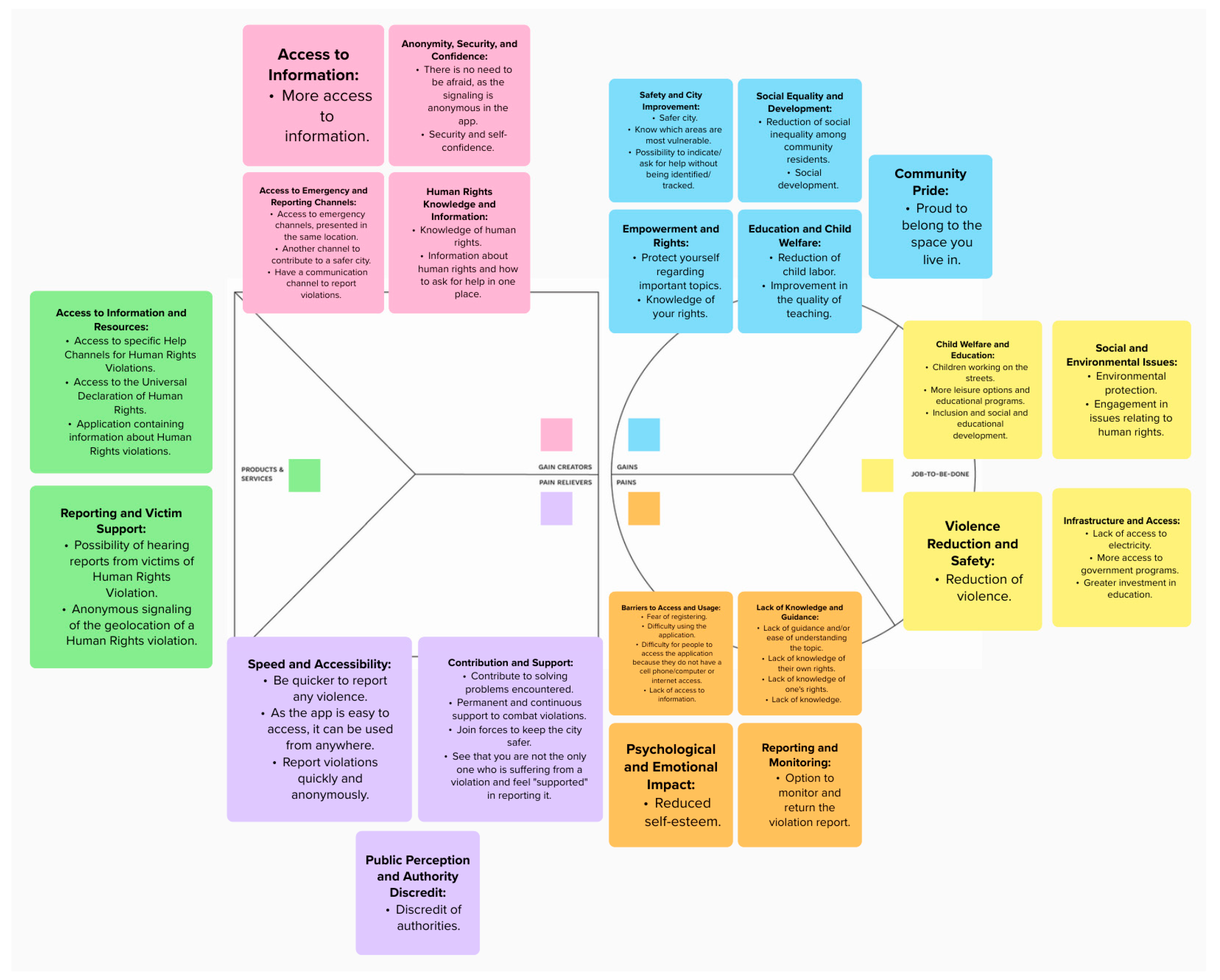

- Customer jobs. The result is presented in Figure 15.

- Families striving for a better life face varied challenges: contributing to income while raising children, finding enriching activities, ensuring safety, and accessing energy and government aid. Each need demands targeted support: alternative child support, educational programs, violence reduction strategies, sustainable energy solutions, and streamlined access to crucial government programs. We can empower families to build brighter futures by addressing these diverse challenges.

- 2.

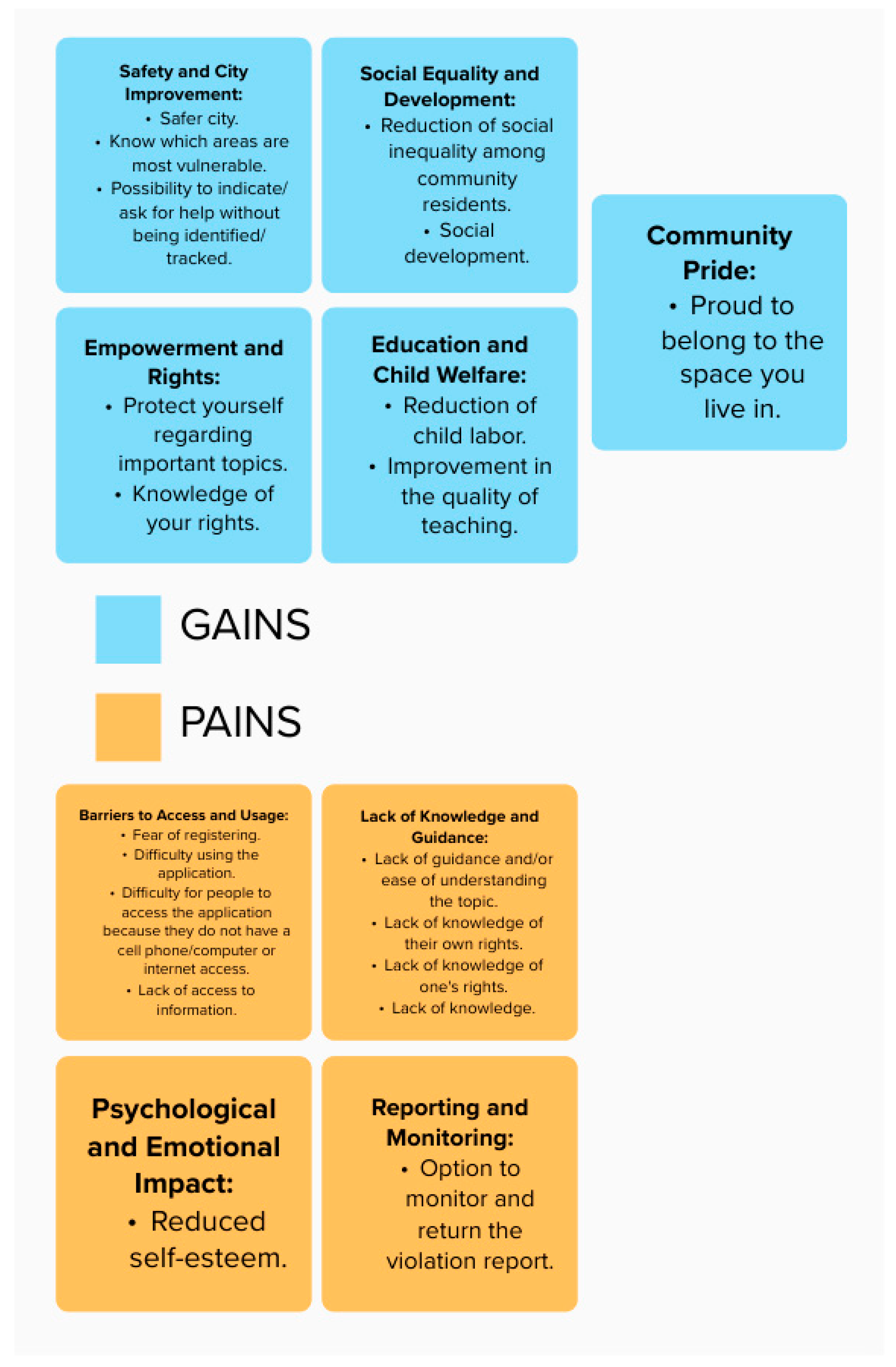

- Pains. The result is presented in Figure 16.

- Potential users face obstacles like fear during registration, requiring empathetic communication and safety assurances. The app’s difficulty requires an intuitive interface, tutorials, and easy navigation support. A lack of understanding points to the need for simple educational resources. Users unaware of their rights suggest the need to incorporate rights education into the app’s value proposition. Finally, accessibility challenges due to device or internet limitations necessitate equitable access strategies, including offline options and public internet partnerships.

- 3.

- Gains. The result is presented in Figure 16.

- This list advocates for protecting children through reduced labor, fostering alternative development paths, and nurturing a safe learning environment through quality education and relevant resources. It emphasizes empowering individuals with knowledge of their rights and tools for self-protection, along with tackling social inequalities for a more equitable and inclusive community.

- 4.

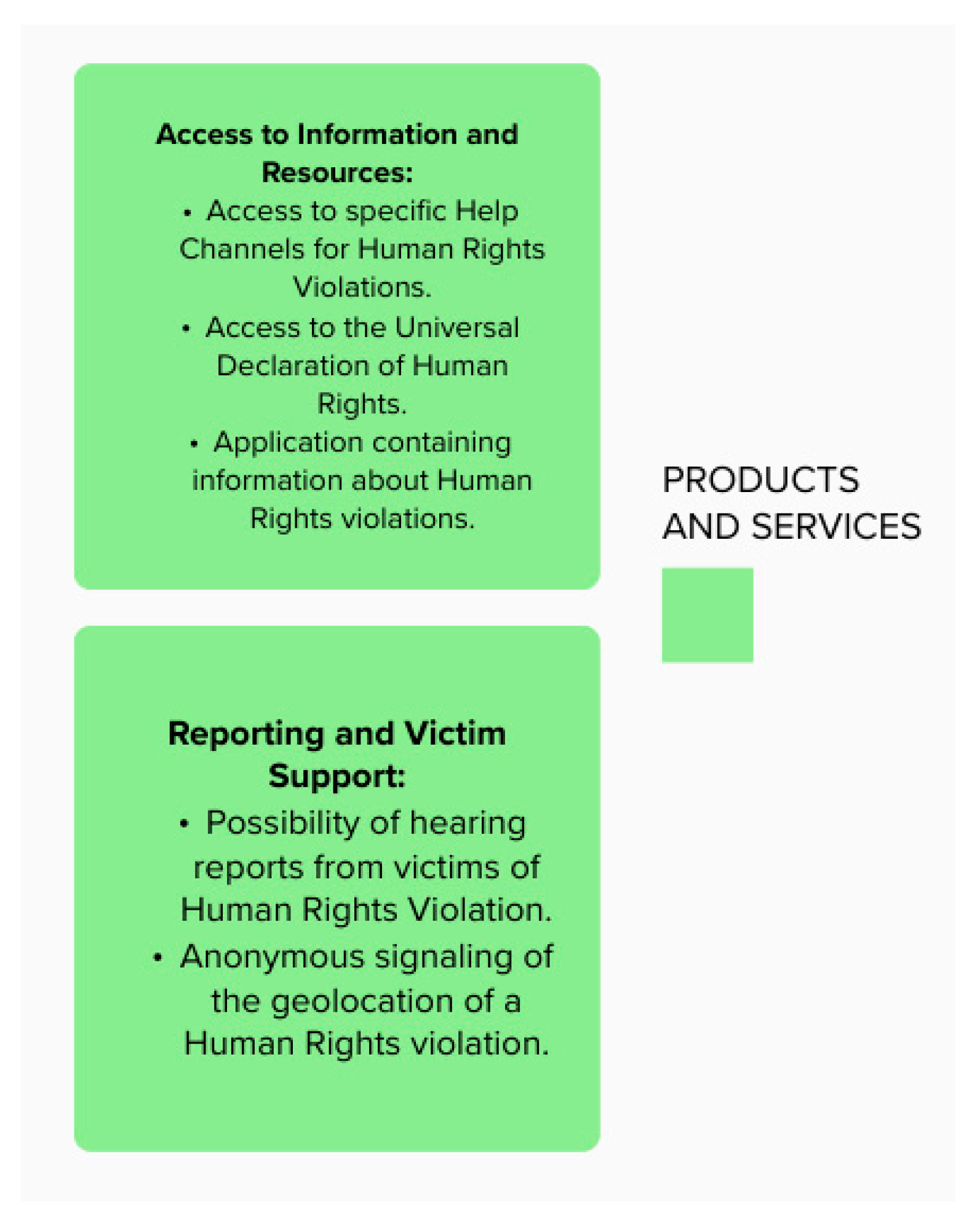

- Products and services. The result is presented in Figure 17.

- This proposed app combats human rights violations by offering specialized support channels, access to the Universal Declaration, and a centralized database of reports. Victims can anonymously share their stories, fostering empathy and community action, while anonymous location flagging prioritizes security and encourages widespread participation.

- 5.

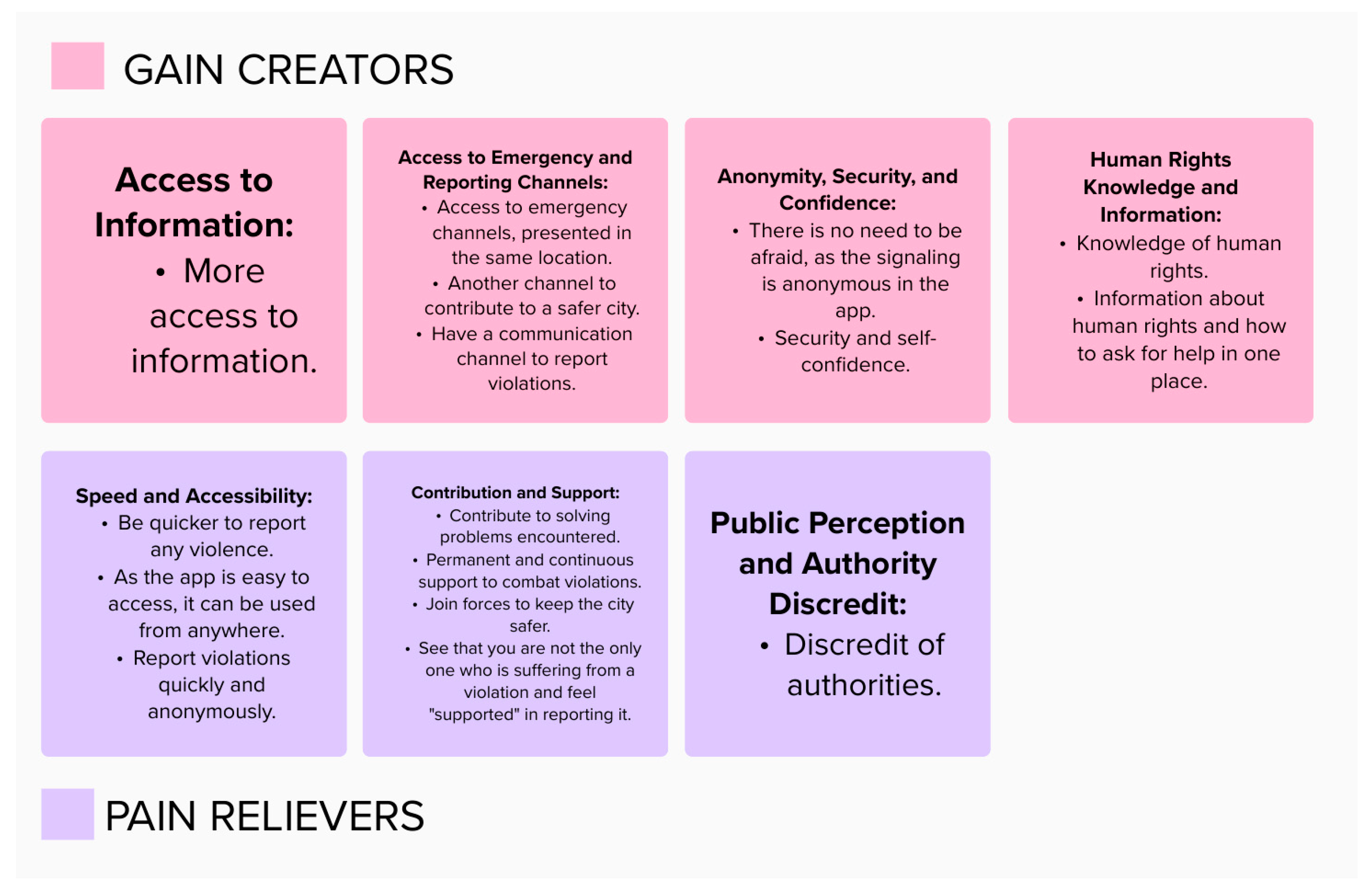

- Gain creators. The result is presented in Figure 18.

- Empowering you with a safer city: Our app lets you report emergencies, find human rights information, and contribute to community safety, all anonymously. It is your one-stop platform for knowledge, security, and a voice against injustice.

- 6.

- Pain relievers. The result is presented in Figure 18:

- This app tackles violence head-on by streamlining reporting, offering immediate support, and fostering community involvement. Easy access, anonymity, and ongoing assistance empower users to address issues directly, building a safer city with trust and collaboration, not fear and isolation.

2.4.3. Design Thinking—Day 3

- What was your understanding as you navigated through the solution?

- How did you feel while trying out the solution?

- How would using My Human Rights—Smart City impact your daily life?

3. Discussions and Learnings with the Software Tool, Developed with the Possibility of Geolocating Violations of Fundamental Human Rights

- Summary of what is fundamental human rights;

- Summary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights;

- List of human rights violations, including environmental rights;

- Channel to report human rights violations, with geolocations of human rights violations by type of violation, city, and neighborhood;

- Video content with reports of violations suffered by other people, serving as an inspiration.

- It raises awareness among the population about the importance of human rights and the risk of violation.

- It adheres to the method used in studies, including the design thinking (DT) sessions with the participation of users specializing in project management for smart cities.

- It uses storytelling to prevent human rights violations in a smart city.

- It notes that the content included in the “My Human Rights—Smart City” application can be considered a sufficient first version but requires improvements with use by the general population.

- It finds that, in smart cities, the use of technology has two biases: the first privileges those who have access to the internet, and the second further excludes people who do not have access to this type of technology.

- It shows the process of continuous application improvement needs to be constant, with users sponsoring its use in the regions where the projects are implemented.

- Include video content with testimonies from people who have suffered human rights violations. These testimonials can be even more effective in raising awareness about the topic.

- Include video content with tips on how to prevent human rights violations. This content can help people take action to protect their rights and the rights of other people. (The first and second improvements can be contributed as SDG 4 (quality education) for the most vulnerable citizens [49] and sustainable development [50].)

- Carry out satisfaction surveys with application users. This research can help identify the most relevant and practical content for users.

- Include user interaction through the design thinking method. This can contribute to developing a more practical application for preventing human rights violations.

4. Conclusions

- Use additional studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the “My Human Rights—Smart City” application. Studies need to be carried out with a larger number of people, that is, populations in localities in Brazil already identified as possibly suffering from violations. Researchers from the project’s partner company work in 30 countries and serve 70 million citizens; therefore, they have the power to invest more in the product.

- In addition to the first point addressed, this research also recommends massive dissemination of the application to the general population, especially the most vulnerable population. The company in question can use the application as a social tool to implement smart and sustainable city projects.

- The creation of educational campaigns, partnerships with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other means of evaluating the tool’s effectiveness are also suggested as each country and each location has its own characteristic to be identified as well as its own customs and culture.

- After testing and analyzing a larger audience, the insights obtained can be used to propose public policies in localities to promote fundamental human rights inherent to smart cities. Policies must contribute to creating and continuously promoting safer and fairer environments for all citizens.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, S.; Rahmat, H.; Marshall, N.; Steinmetz-Weiss, C.; Bishop, K.; Corkery, L.; Park, M.; Tietz, C. Merging Smart and Healthy Cities to Support Community Wellbeing and Social Connection. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 1067–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, P.D.C.L.; Da Costa, M.S.; Cataldi, M.; Soares, C.A.P. Management of non-structural measures in the prevention of flash floods: A case study in the city of Duque de Caxias, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Nat. Hazards 2017, 89, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, L. Preventing Long-Term Risks to Human Rights in Smart Cities: A Critical Review of Responsibilities for Private AI Developers. Internet Policy Rev. 2023, 12, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Department of State, United States of America. 1949, Volume 3381. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Portugal, P.H.F.; Moreira, J.F.; Póvoas, M.D.S.; Silva, C.A.F.D.; Guedes, A.L.A. The Favela as a Place for the Development of Smart Cities in Brazil: Local Needs and New Business Strategies. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranrattanasuit, N.; Sumarlan, Y. Failed Mimicry: The Thai Government’s Attempts to Combat Labor Trafficking Using Perpetrators’ Means. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penmetsa, M.K.; Bruque Camara, S.J. Building a Super Smart Nation: Scenario Analysis and Framework of Essential Stakeholders, Characteristics, Pillars, and Challenges. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghayedi, A.; Awuzie, B.; Omotayo, T.; Le Jeune, K.; Massyn, M.; Ekpo, C.O.; Braune, M.; Byron, P. A Critical Success Factor Framework for Implementing Sustainable Innovative and Affordable Housing: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings 2021, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Atobishi, T.; Hegedűs, S. Social Sustainability of Digital Transformation: Empirical Evidence from EU-27 Countries. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo Guedes, A.L.; Carvalho Alvarenga, J.; Dos Santos Sgarbi Goulart, M.; Rodriguez y Rodriguez, M.V.; Soares, C.A.P. Smart Cities: The Main Drivers for Increasing the Intelligence of Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarez RP, F.; Vargas, R.V.; Alvarenga, J.F.; Chinelli, J.K.; Costa, M.A.; de Oliveira, B.N.; Haddad, A.N.; Soares, C.A.P. Sustainability Indicators to Assess Infrastructure Projects: Sector Disclosure to Interlock with the Global Reporting Initiative. Eng. J. 2020, 24, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Assembly. Sustainable Development Goals. SDGs Transform. Our World 2015, 2030, 6–28. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, K.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; Ferguson, F.J.; Brindley, P. A Smartphone App for Improving Mental Health through Connecting with Urban Nature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellmann, S.; Maryschok, M.; Schöffski, O.; Emmert, M. The German COVID-19 Digital Contact Tracing App: A Socioeconomic Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, T.H. Enforcement of the Use of Digital Contact-Tracing Apps in a Common Law Jurisdiction. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, G.; Carnevali, D. Smart Justice in Italy: Cases of Apps Created by Lawyers for Lawyers and Beyond. Laws 2022, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faza, A.; Rinawan, F.R.; Mutyara, K.; Purnama, W.G.; Ferdian, D.; Susanti, A.I.; Didah, D.; Indraswari, N.; Fatimah, S.N. Posyandu Application in Indonesia: From Health Informatics Data Quality Bridging Bottom-Up and Top-Down Policy Implementation. Informatics 2022, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista Silva, A.; Malta, M.; da Silva, C.M.F.P.; Kalume, C.C.; Filha, I.G.A.; LeGrand, S.; Whetten, K. The Dandarah App: An mHealth Platform to Tackle Violence and Discrimination of Sexual and Gender Minority Persons Living in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. UN-E-Government Survey 2022. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2022 (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General. Global Sustainable Development Report 2023: Times of Crisis, Times of Change: Science for Accelerating Transformations to Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2024; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; 196p, Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/world-economic-situation-and-prospects-2024 (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- UN-HABITAT. World Cities Report 2022. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Ramírez-Moreno, M.A.; Keshtkar, S.; Padilla-Reyes, D.A.; Ramos-López, E.; García-Martínez, M.; Hernández-Luna, M.C.; Mogro, A.E.; Mahlknecht, J.; Huertas, J.I.; Peimbert-García, R.E.; et al. Sensors for Sustainable Smart Cities: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, H.d.C.I.; Xavier, G.S. Uma análise crítica acerca dos direitos humanos frente ao seu relativismo sistêmico: Uma realidade além da hermenêutica. Rev. Quaestio Iuris [S.L.] 2021, 14, 1104–1125. Available online: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/quaestioiuris/article/view/50453 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Conference of the Parties (COP)|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process/bodies/supreme-bodies/conference-of-the-parties-cop (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Hassani, H.; Huang, X.; MacFeely, S.; Entezarian, M.R. Big Data and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) at a Glance. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.; Tairov, I. Solutions to Manage Smart Cities’ Risks in Times of Pandemic Crisis. Risks 2022, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Desenvolvimento como Liberdade; Companhia de Bolso: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. The idea of justice. J. Hum. Dev. 1999, 9, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Ortega, O.; Dehbi, F.; Nelson, V.; Pillay, R. Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, C. From a Vicious to a Virtuous Circle: Addressing Climate Change, Environmental Destruction and Contemporary Slavery (Anti-Slavery, 2021). Available online: https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ASI_ViciousCycle_Report_web2.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Torres, D.H.A.; da Costa Dias, F.; Bahiana, B.R.; Haddad, A.N.; Chinelli, C.K.; Soares, C.A.P. Oil Spill Simulation and Analysis of Its Behavior Under the Effect of Weathering and Chemical Dispersant: A Case Study of the Bacia de Campos—Brazil. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cima, E. The right to a healthy environment: Reconceptualizing human rights in the face of climate change. Reciel 2022, 31, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organisations and Inspires Innovation; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Design Thinking: Uma Metodologia Poderosa para Decretar o Fim das Velhas Ideias/Tim Brown com Barry Katz: Tradução Cristina Yamagami—Rio de Janeiro; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; 249p. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, G.A.; Kenny, R.F. Using Design Thinking and Formative Assessment to Create an Experience Economy in Online Classrooms. J. Form. Des. Learn. 2021, 5, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgorn, E.; Hendriks, M.; Geurts, L.; Bakker, C. A Storytelling Methodology to Facilitate User-Centered Co-Ideation between Scientists and Designers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, N.; Rosli, H.; Juhan, M.S. The Creative Process: Developing Visual Storytelling through Design Thinking. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Z. Book Review: Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2014, 15, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, W.D.; De Meyst, K.; Eaton, T.V. The Impact of Human Rights Reporting and Presentation Formats on Non-Professional Investors’ Perceptions and Intentions to Invest. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amila, K.; Umemuro, H. The Impact of Affect and Leadership on Group Creative Design Thinking; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 892–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constituição do Brasil. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF: Presidente da República. 2016. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Enel de SP Teve Lucro Bilionário: Qual o Tamanho Dela no Brasil e no Mundo? Available online: https://economia.uol.com.br/noticias/redacao/2023/11/10/enel-distribuidora-de-energia-municipios-sp.htm (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- ENEL. Enel Brasil: Apresentação Institucional, São Paulo, 07 de Março de 2023. Apresentação. 2023. Available online: https://ri.enel.com/Documento/DownloadPublicFile?fileNameKey=40d812f0-cc1e-404d-a2b5-96e1190dd416.pdf&tipoPath=1 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Martin, R. The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R. Wicked problems in design thinking. Des. Issues 1992, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorino, G.; Bandeira, R.; Painho, M.; Henriques, R.; Coelho, P.S. Rethinking the Campus Experience in a Post-COVID World: A Multi-Stakeholder Design Thinking Experiment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.-N.-M.; Hoang, L.-K.; Le, C.-M.; Tran, T. A Human Rights-Based Approach in Implementing Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) for Ethnic Minorities in Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Os Limites à Efetivação da Dimensão Social do Direito Humano ao Desenvolvimento Sustentável|Revista Direitos Fundamentais & Democracia. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.25192/issn.1982-0496.rdfd.v26i31705 (accessed on 21 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souza, R.M.; Cezario, B.S.; Affonso, E.O.T.; Machado, A.D.B.; Vieira, D.P.; Chinelli, C.K.; Haddad, A.N.; Dusek, P.M.; Miranda, M.G.d.; Soares, C.A.P.; et al. My Human Rights Smart City: Improving Human Rights Transparency Identification System. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031274

Souza RM, Cezario BS, Affonso EOT, Machado ADB, Vieira DP, Chinelli CK, Haddad AN, Dusek PM, Miranda MGd, Soares CAP, et al. My Human Rights Smart City: Improving Human Rights Transparency Identification System. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031274

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouza, Roberto M., Bruno S. Cezario, Estefany O. T. Affonso, Andreia D. B. Machado, Danielle P. Vieira, Christine K. Chinelli, Assed N. Haddad, Patricia M. Dusek, Maria G. de Miranda, Carlos A. P. Soares, and et al. 2024. "My Human Rights Smart City: Improving Human Rights Transparency Identification System" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031274

APA StyleSouza, R. M., Cezario, B. S., Affonso, E. O. T., Machado, A. D. B., Vieira, D. P., Chinelli, C. K., Haddad, A. N., Dusek, P. M., Miranda, M. G. d., Soares, C. A. P., & Guedes, A. L. A. (2024). My Human Rights Smart City: Improving Human Rights Transparency Identification System. Sustainability, 16(3), 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031274