Abstract

Although prior research has highlighted the importance of social media in promotion and communication, a comprehensive framework to clarify how to use social media as a value co-creation platform to promote a green lifestyle has yet to be developed. This research aims to create and test a conceptual model for using social media as a value co-creation platform to encourage and motivate people to adopt a sustainable green lifestyle, besides mapping the process of green lifestyle adoption from the actual social media user behaviors. Two hundred and eighty-nine (289) subjects participated in an online survey in the first half of 2022, and the data collected have been analyzed using regression. The three key findings: (1) social media contact is positively associated with a sustainable green lifestyle (β = 0.234, p < 0.001); (2) value co-creation partially mediates the relationship between social media contact and a sustainable green lifestyle (indirect effect = 0.113, with Sobel test’s t-value = 5.762); and (3) surprisingly, the moderating role of social media influencers and social norms in the social media contact–sustainable green lifestyle relationship is not supported. In addition, this research supplied some reasonable and practical implementations that can help green agents and policymakers promote green behaviors.

1. Introduction

In recent years, dramatic climate change has been an increasingly contested topic; it is easy to see how environmental challenges negatively influence people’s lives. Most countries now agree on the fundamental notions of climate change and collaborate on international initiatives like the Paris Agreement [1]. They also agree that carbon emissions are the primary source of climate change. As the world’s top carbon emitter, China is now facing a significant challenge in reducing this and has promised to peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and attain carbon neutrality by 2060 [2]. Hence, to effectively mitigate environmental issues, aside from the government’s policies, the general public can contribute by changing how they live and consume natural resources and by adopting a sustainable green lifestyle [3].

Remarkably, social media has become an increasingly significant form of entertainment in users’ daily lives, as it aids in disseminating vital information. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to people spending more time at home and, as a result, more time on social media, particularly among younger generations [4,5]. The most powerful influence of social media is through electronic word of mouth (eWOM), in which users create regular shares, likes, comments, and discussions on such platforms [6]. Due to ubiquitous connections and the ability to reach many people via a single post, the significance of using social media for developing a sustainable green lifestyle should not be underestimated.

Prior research has investigated the link between social media and public awareness of climate change. For example, Anderson [7] found some evidence of social media influencing people’s opinions, knowledge, and behavior. She suggested sharing information via social media can promote awareness and inspire individuals to engage in more environmentally friendly activities. Chung et al. [8] also found that young people obtained environmental and green information through social media but seldom shared such information. Meanwhile, See-To and Ho [6] indicated that social media contributes to value co-creation through interactions between users and social media owners, thus influencing the users’ behavior.

Therefore, we conjecture the contribution of social media as a trigger and support tool to spread knowledge and information for advocating green lifestyle adoption under a value co-creation approach. This can provide a valuable channel for promoting a green lifestyle, thus contributing to the environmental challenges of the world’s rapid urbanization.

Despite prior research emphasizing the role of social media in promoting sustainable behaviors, few works have comprehensively and systematically explained what value co-creation behaviors drive individuals to embrace a sustainable green lifestyle. Moreover, unlike most studies, this research takes a finer-grained approach. It distinguishes between two types of value co-creation activities, one focusing on the impact of social media influencers (SMIs) [9] and the other focusing on the influence of social norms (SNs) [10]. We want to find evidence about how these two aspects can influence the public’s value co-creation behaviors that enhance the link between social media engagement and green lifestyle adoption.

In addition, although environmental issues are becoming more widely recognized, most research on environmental behaviors has focused on developed countries. However, research studies based on China are limited despite its severe environmental challenges and large population. Therefore, we designed this study to investigate whether social media is a suitable channel to influence people to adopt a greener lifestyle in mainland China [3].

We intend to create and test a conceptual model for using social media as a value co-creation platform to encourage people to embrace a sustainable green lifestyle. The model also aims to map the process of green lifestyle adoption based on the actual behaviors of social media users. In particular, we are interested in the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1:

- Is social media contact positively associated with a sustainable green lifestyle?

- RQ2:

- Can value co-creation behaviors partially mediate the social media contact–sustainable green lifestyle link?

- RQ3:

- How do social media influencers and social norms moderate the value co-creation behaviors in the green lifestyle adoption process?

To investigate these research questions, this research developed a conceptual model based on Ho et al. [11] by adding social media influencers and norms as the new moderators. Hypotheses were developed from our research model, and we conducted an online survey to collect data from mainland China for regression analyses. As mentioned above, China aims to achieve its carbon neutrality by 2060, and it needs to convert its people’s lifestyle to a sustainable green lifestyle as soon as possible to achieve this goal [3].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Background of Social Media

Social media refers to web tools functioning as social communication channels for community-based input, interaction, content sharing, and collaboration [12]. Specifically, to distinguish from traditional media, this research acknowledges the literature’s definition of social media and identifies the following commonalities among current social media services: (i) Social media services are Web 2.0 Internet-based applications; (ii) User-generated content is social media’s lifeblood; (iii) Individuals and groups construct user-specific profiles for a social media service’s site or app that is developed and managed; and (iv) By connecting a profile with other individuals or groups, social media platforms make it easier to build online social communities [13].

Today, people are more exposed to the world of social media. The total of global social media users is growing at a rate of 13 new users per second, quicker than in the pre-pandemic period. With double-digit annual growth, worldwide social media users have risen to 4.62 billion. Current trends suggest that it will have surpassed 60% of the global population within the next few months. At the same time, social media platforms like YouTube, WeChat, Facebook, TikTok, etc., have become increasingly popular to appeal to the target user through creative content and strategies [14].

Individuals can enjoy social connections through social networks with digital devices to fulfill their individual, professional, and leisure reasons [14]. The forms of social media are expanding for purposes like media sharing (such as Weibo, YouTube, and Instagram), instant messaging (such as WeChat and WhatsApp), social networking (such as Facebook and Redbook), experience and resource-sharing tools (such as Twitter), etc.

Scholars divide social media usage into expressive and consumptive categories [15]. The direction explored in this research is expressive, which is about expressing one’s opinion, sharing or discussing preferences via social media, and engaging in activism [16]. To summarize, one fundamental perspective in the social media literature is that online and offline expression can both increase opinion voicing and action on significant social issues [7].

Since there is an increasingly massive population of social media users, the researcher reviewed studies from different domains conducted to investigate the drives and impact of social media usage (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Drives and impacts of social media usage.

2.2. Value Co-Creation in Social Media

Prahalad and Ramaswamy [22] developed the concept of value co-creation, which states that the service provider and the users jointly create the value of a service. In recent years, academics have applied this concept to various problems in various domains. They discovered that customers are value co-creators, a basic premise that applies to value co-creation [23]. Moreover, an emerging view of value creation is due to users’ capabilities to attribute their meanings, experiences, and contexts and then share them with others [24].

Academics view social media as platforms that allow businesses to innovate and boost their reputation, success, and sustainability [25]. Thus, it constitutes an excellent medium for value co-creation by allowing users and stakeholders to collaborate on brand image and values, leading to desired behaviors. Furthermore, behavioral alignment and empowerment and control are two possible value co-creation constructs with specific links to the construction of value co-creation in social media platforms [6]. Some companies have used social media to develop new business possibilities and strategic management practices while enhancing organizational effectiveness by reorganizing current business resources and procedures [24].

2.3. Sustainable Green Lifestyle and Adoption

The concept of sustainable development originated in the 1960s when people began arguing about the impact of economic growth on the environment [26]. Since then, various definitions of sustainability and sustainable development have been proposed and debated, but the most widely accepted one was published in the report “Our Common Future” (i.e., the Brundtland Report) in 1987, which defined sustainable development as “To meet the demands of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” [27].

The term “green lifestyle” or “ecological lifestyle” refers to a modern way of life that includes services, laws, guidelines, and policies that cause no or minimal harm to ecosystems or the environment [28]. Prior studies had many discussions and developed various definitions for a green lifestyle, such as simplicity being an essential feature of such a lifestyle [29] and sustainability being an essential aspect of it [30]. Therefore, we define the “sustainable green lifestyle” as a “green lifestyle” that corresponds to the “sustainable development requirements” in this research.

After realizing that environmental challenges are growing more significant, many consumers are becoming more attracted to environmentally responsible actions known as the green lifestyle. Rather than focusing on the obstacles or motives for purchasing green products, we focus on encouraging people to embrace a green lifestyle, including various behaviors shown in Table 2, such as purchasing sustainable products and services [31] and non-purchase behaviors [28]. Also, researchers are interested in the causes and effects of adopting an eco-friendly lifestyle as people become increasingly aware of its importance (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Behaviors of a sustainable green lifestyle.

Table 3.

Drives and impacts of sustainable green lifestyle adoption.

2.4. Social Media Influencers

Social media influencers (SMIs) are emerging as a new trend in marketing and communication. They are people with a reputation or significant influence on others and can communicate to an unknown mass audience in the digital world [41]. With the rise of social media, SMIs have become an increasingly broad concept. Ogilvy Consultant [9] classified social media influencers into three types based on fame, engagement, and audience: traditional awareness influencers (such as celebrities, etc.), digital influencers (such as YouTubers, Instagrammers, Bloggers, etc.), and consumer-driven brand advocates (including brand fans, etc.). Through the influencers’ life sharing and recommendations, employing SMIs to attract social media users’ attention and establish their reliability has become a successful marketing strategy [42].

Regarding how SMIs influence audience behavior, Zhu and Chen [43] suggested that self-esteem may influence decision-making, i.e., replicating or copying the SMIs’ styles (e.g., buying the same bags, shoes, and clothes, or similar lifestyles). Regarding the green lifestyle context, Chwialkowska [28] explored how eco-lifestyle SMIs drive green lifestyle adoption using the minority influence model. She proposed four key elements: message consistency, a non-dogmatic approach, involving the majority in systematic thinking, and stimulating identification through normalizing green behaviors. Green lifestyle influencers can exert informational influence and value co-creation behavior by presenting information-rich content that integrates these four characteristics.

2.5. Social Norms and Green Behavior

Concerning the green lifestyle, social norms are defined as common cultural values that express common knowledge through shared integration of social groupings regarding what other people think or should do about environmental issues and challenges. This illustrates social acceptability and unacceptance by emphasizing what must or should not be done to avoid the consequences of defying worldwide standards [10]. Social norms exist in many aspects of human behaviors; they may be descriptive, like a person’s opinions about a prevalent behavior [44]; injunctive, such as what a person thinks they must do to avoid rejection [45]; or subjective, for instance, a person’s perception of the behavior others expect [46].

Ho et al. [11] reported that perceived benefits, social norms, attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors are significant in sustainable living. Furthermore, regarding how normative appeals encourage sustainable consumer behaviors, White and Simpson [47] reported that the effectiveness of the appeal type depends on whether the individual or collective level of the self is activated. Subjective appeals, which emphasize the benefits of the action, are less effective at promoting sustainable behaviors when the collective level of self is activated. Instead, injunctive and descriptive appeals are more effective. Subjective and descriptive appeals are helpful when the individual level of self is engaged. The benefits of knowledge such appeals might offer depend on their beneficial effects on the individual self.

2.6. Research Gap and Model

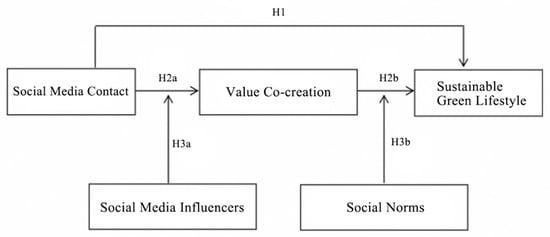

Social media has rarely been investigated as a venue for distributing sustainability and green knowledge to the public. Limited information is available on the green lifestyle’s non-purchase behaviors, such as information sharing, disposal, recycling, and reuse. We developed our research model based on two theoretical frameworks to explore how social media could contribute as a value co-creation platform for promoting a sustainable green lifestyle.

The research’s first framework to guide our research model was developed by Ho et al. [11], which incorporated a conceptual model adapted from the Integrated Waste Reduction Model [48] and how social media could contribute to value co-creation [22]. This framework attempted to compare how traditional media and social media can be used to promote and engage young people in adopting an environment through their interactions. Particularly, this framework proposed that social media contact would influence sustainable green lifestyles directly, and value co-creation would mediate this effect. Therefore, we proposed the following two sets of hypotheses.

H1.

Social media could be an effective tool for motivating individuals to adopt a green lifestyle. As a result, the pertinent information supplied to the public via social media (social media contact, SMC) is positively related to a sustainable green lifestyle.

H2a.

Social media contact is positively related to the extent of value co-creation behaviors in its sustainable green lifestyle adoption.

H2b.

Value co-creation behaviors are positively related to a sustainable green lifestyle.

H2c.

Value co-creation behaviors mediate the relationship between this social media contact and a sustainable green lifestyle.

The second framework focuses on how social agents (in this research, green lifestyle influencers) employ informational influence to motivate early modeling behaviors, which is then reinforced by normative influence through peer communication and community involvement. According to the theoretical paradigm, both informational and normative influences are preserved and increased through peer learning and socialization. As a result, this research investigates how the two concepts work together to explain why people live green lifestyles.

People have viewed social media as beneficial for building social capital and civic engagement in social issues. We anticipate social media can help the community spread sustainable messages and knowledge to people [49]. In addition, SMIs and social norms play a vital role in this process. Because SMIs coincide with the range of Minority Influencer Theory [50], and social norms belong to the social learning process, we assume these two factors also play a role in behavioral change. Therefore, we propose the following set of hypotheses.

H3a.

Social Media Influencers can moderate the association between social media contact and value co-creation behaviors, strengthening the relationship for individuals/agents with more informative influence.

H3b.

Social Norms can moderate the relationship between value co-creation behaviors and sustainable green lifestyle adoption, such that the relations are stronger for agents, enabling the diffusion of behavioral norms.

Figure 1 shows our conceptual model with the proposed hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methodology

We collected data through a survey to find empirical support for our model in the first half of 2022. Our model comprised six constructs adapted from Ho et al. [11], i.e., social media contact (SMC), value co-creation (VC), sustainable green lifestyle (SGL), social media influencers (SMIs), social norms related to social media (SNSM), and social norms (see Appendix A).

The online questionnaire was conducted via Wenjuan.com and comprised three parts. Part A asked about participants’ demographic information, and Part B asked about the experience of living a sustainable green lifestyle and social media usage. Part C consisted of survey items of a 7-point Likert scale of our constructs.

Our participants were mainly Chinese who have experienced receiving information on social media and have used at least one type of social media platform. The questionnaire was first uploaded on Wenjuan.com. Later, this weblink was shared on various social media platforms (such as WeChat, Weibo, and Douban) to reach the maximum number of people. Thus, the non-response rate cannot be reported.

After data collection, SPSS was used for various analyses, including participants’ demographics, factor analyses, and regression, to test the proposed research model.

4. Results

We collected 289 valid responses, of which 168 were female (58.13%) and 121 were male (41.87%) (see Table 4). Age was mainly concentrated in the 18–25 range (80.28%), followed by the 26–30 range (9.34%). Regarding educational level, most had a bachelor’s degree (51.21%), followed by a master’s (41.87%). Therefore, more than 90% of our participants earned at least a bachelor’s degree and can be considered well-educated. Most of their occupations were full-time study (61.59%), followed by employment in the private sector (19.38%). Most of their monthly income was between RMB 7001 and 10,000 (17.13%), and almost half of the participants’ monthly income was over RMB 5000. Aside from 247 participants from China and Hong Kong (85.47%), 42 participants (14.53%) were from overseas (including France, Australia, the UK, and Switzerland) who were Chinese studying or working in these countries.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics (n = 289).

5. Data Analysis

One third of our participants indicated that they had never lived a sustainable green lifestyle or had lived one for less than one year, and another one third lived a green lifestyle between 1 and 4 years. Only 33 (11.42%) had lived a green lifestyle for over ten years. In addition, we asked our participants to report the percentage of living a sustainable green lifestyle. Most of them (30.45% of our participants) reported that 21–40% of the time they followed a green lifestyle, with an average score of 43.86%.

Concerning their social media usage patterns (see Table 5), the most frequently used social media platforms were instant messengers, such as LINE, WhatsApp, and WeChat, followed by video-sharing platforms like YouTube and Bili Bili.

Table 5.

Social media usage frequency (n = 289).

5.1. Validity of Survey Instrument

Table 6 shows the results of the factor analysis. The result of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test is 0.925 (>0.7), which reflects that the factors in our models are reliable. The p-value of the Bartlett test is <0.001, which reflects that all variables under those dimensions are suitable for conducting factor analysis. Harman’s one-factor test (41.62% < 50%) and test of variance inflation factors (VIFs, with results below 5) for all the variables in the regression analysis were conducted before further analysis. Therefore, the analysis does not have multicollinearity problems, and there is also no substantial concern regarding common method variance bias [51].

Table 6.

Factor loading.

The convergent validity is achieved, as all t-values of the factor loadings are significant with p < 0.01 and Cronbach’s α values > 0.70. The discriminant validity is also achieved, as all instrument items have a loading > 0.7 on their associated factors after removing items VC5, VC6, and SGL1 and have a low loading on other factors [52]. Further, the square root of the average variance extracted from each latent construct in Table 7 is greater than the correlation of the construct concerned with other constructs in the model.

Table 7.

Correlation matrix.

5.2. Regression Analyses

Data collected were analyzed using multiple regression. The continuous independent variables of these regression models were mean-centered before constructing interaction terms in moderated regression models to improve the interpretation of the regression coefficients [53]. In these regression analyses, we included our participants’ self-reported experience of living a sustainable green lifestyle (green years) and their percentage of living a sustainable green lifestyle (green percentage) as control variables.

This research first used the four-step approach proposed by Baron and Kenny [54] to test whether VC mediated the relationship between SMC and SGL, as per H1 and H2a to H2c. Our result is shown in Table 8. Equation (1) was developed to test H1. The coefficient of SMC was positive and significant (β = 0.234, p < 0.001) and supported H1, indicating that the SGL performance improved as SMC increased.

Table 8.

The mediating role of value co-creation.

H2a was tested using Equation (2). Results indicated that H2a is supported, as the coefficient of SMC is positive and significant (β = 0.415, p < 0.001), indicating that the higher the SMC, the higher its VC.

To test the effect of VC on SGL (i.e., H2b), we developed Equation (3). Results indicated that H2b is also supported, as the coefficient of VC is positive (β = 0.337, p < 0.001), indicating that the higher the VC, the higher the SGL performance.

Equation (4) was developed to test for the mediating effect of VC. The coefficient of SMC (β1 = 0.121, p < 0.01) and VC (β2 = 0.273, p < 0.001) were both significant, showing that VC partially mediated the relationship between SMC and SGL. The indirect effect was 0.113 (= 0.234–0.121), and the result of the Sobel test was t = 5.762.

The moderating role of SMI was tested in the link between SMI and VC (i.e., H3a) using multiple regression. Table 9 shows the regression results. The baseline model with the main effects only is Equation (2). Equation (5) includes SMC and SMI, and Equation (6) includes SMC, SMI, and their interaction.

Table 9.

Moderating role of SMI in the SMC–VC relationship.

The moderating effect can be analyzed in two ways. The first is to check the change in F-value from Equation (5) to Equation (6); the second is to view the significance of the interaction term in Model 3. We noted that H3a is not supported because (i) the change of F-value was negative, and (ii) the coefficient for SMC×SMI was insignificant (p = 0.651).

Similarly, H3b was tested on the moderating role of social norms, including social norms–social media (SNSM, see Table 10) and social norms–daily life (SND, see Table 11), in the relationship between VC and SGL. The baseline model with the main effects only is Equation (3). Equation (7) includes VC and social norm (i.e., SNSM for Table 10 and SND for Table 11), and Equation (8) includes VC, SN, and their interaction.

Table 10.

Moderating role of social norms (social media) in the VC–SGL relationship.

Table 11.

Moderating role of social norms (daily life) in the VC-SGL relationship.

However, the interaction between value co-creation and social norms was insignificant for social norms–social media (p = 0.123) and social norms–daily life (p = 0.055). Therefore, the moderating roles of social media influencers and social norms in the SMC-SGL link are not supported.

6. Discussion

6.1. General Discussion of RQs

Social media has become a common form of communication and occupies a significant proportion of urbanites’ social lives [12]. RQ1, which H1 tested, proposes that social media contact is positively associated with a sustainable green lifestyle. Participants undoubtedly use social media as their primary information source for finding ideas and news related to sustainability. From the demographic information (see Table 4) and regression analyses in Table 8, participants notably utilize social media to spread environmental consciousness and receive information on a sustainable green lifestyle. This finding means social media contact is conducive to adopting greater sustainable green lifestyle performance, aligning with the findings of some recent studies [8,11]. Social media has gained credibility as a reliable source of information and a venue for frequent user interaction. Meanwhile, information about sustainability can be presented in various ways, such as text, audio, video, and pictures, as well as in VR and AR [55].

This research also offers various insightful perspectives and strategies to alter people’s behavior relevant to green organizations promoting an environmentally sustainable lifestyle. RQ2, which H2a to H2c tested, investigates how value co-creation mediates the relationship between social media contact and a sustainable green lifestyle. Our finding supports this RQ, and this result suggests to green agencies that value co-creation is the fundamental mechanism through which social media interaction affects its performance in promoting a sustainable green lifestyle. Meanwhile, social media facilitates effective collaboration, aligning with Chung et al. [8]. Moreover, social media users are willing to engage in value co-creation activities, aligning with See-To and Ho [6].

Although the participants did not frequently interact with the posts about sustainability and environmentalism, they did care about this kind of discussion. Prior research suggests that “peer pressure” is a passive motivation for people to engage in sustainability behaviors [56] when they regularly see sustainability content. This is the focus of our RQ3, which H3a and H3b tested, to investigate how social media influencers and social norms moderate the value co-creation behaviors in the green lifestyle adoption process. However, contrary to our expectations, the moderating role of social media influencers and social norms in the social media contact–sustainable green lifestyle relationship is not supported. This result shows no evidence that social media influencers’ posts on sustainability knowledge and environmental severity would positively impact the public’s autonomy to adopt a better lifestyle. Moreover, the results show that social norms and social values might not influence a person’s intention to engage in green behaviors.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

Although social media is increasingly adopted for acquiring sustainability information, there is still a limited grasp of how it affects living sustainably. This study adds to the knowledge regarding the real-world use of social media and sustainability. Our findings imply that social media engagement can facilitate the adoption of a sustainable green lifestyle because sustainability is essential to most countries’ profitability and long-term performance.

Another significant contribution is discovering a pathway by which social media contact is connected to sustainable green lifestyles. The findings imply that social media interaction enhances value co-creation in sustainable green lifestyle adoption, and value co-creation acts as a mediating factor in the relationship between them. A significant moderating function belongs to value co-creation for two reasons. First, it adds to the body of research on social media by illuminating a hitherto unknown link between social media contact and value co-creation. Second, previous research has mainly concentrated on the outcomes of value co-creation but has not fully explored the factors that affect it [6]. Our finding expands the body of knowledge by pinpointing the causes of value co-creation in the context of sustainable green lifestyle adoption.

6.3. Practical Implications

Sustainability has received tremendous attention in recent years. Many countries are pressured to respond to and act on societal and environmental needs in their policies [57]. Our findings document a positive association between social media contact and sustainable green lifestyle performance and unveil value co-creation as the mediational pathway through which social media contact contributes to sustainable green lifestyle performance. Based on these results, recommendations and implementation can be provided to help green agents and policymakers to promote green activities.

Even though not everyone would actively post or share information on a green lifestyle on social media, most people believe living sustainability is essential and are prepared to dedicate themselves to doing so [8]. Consequently, considering the public often passively receive messages on sustainability topics, green agencies should dedicate resources to cultivating their social media contact to increase their interactions with people. Practical means include opening different social media channels, putting the promotion team on their priority agenda, and developing mindfully embedded sustainability initiatives within the context of broader strategic requirements.

Given the theoretical support for the modest use of social media tools in sustainability, government and policy encouragement and support are essential. Meanwhile, the usage of social media can benefit internal knowledge sharing and creativity as well [58]. Such activities allow organizations to continuously update their value co-creation behaviors and effectively communicate and realize the potential benefits of social media technologies for adopting sustainable green lifestyles [8].

More specifically, environmentalists, policymakers, and green agencies can make efforts to raise awareness of the value of environmental conservation and education by providing the general public with interesting and helpful tips, instructions, materials, events, or activities on social media [8]. For instance, to attract users, they should fulfill what they lack. Suppose users said they lacked sufficient knowledge to classify their waste appropriately, purchase eco-friendly goods, etc. In that case, we could produce content about these knowledge gaps to help them adopt an eco-friendly habit. Apart from this, individuals should improve their news literacy to become better information receivers, thus being more active in spreading knowledge and customs about sustainability through online social networks with family and friends [8].

7. Conclusions

Research on sustainability has received increasing attention worldwide. While different research areas have been explored, the study on the moderating role of value co-creation behaviors remains limited due to the novelty and lack of theory. On the other hand, social media influence is more prevalent than ever because of its rapid development. After seeing the influence of social media influencers and social norms on users’ behavior in earlier studies, we developed this study to investigate the impact of these factors on regulating value co-creation when adopting a green lifestyle. More specifically, we created and tested a conceptual model using social media as a value co-creation platform to encourage and motivate people to adopt a sustainable green lifestyle. Quantitative methods were used to find empirical support for our model.

Notably, while this research is rigorous in the research procedure, several research limitations should be mentioned. First, this study used a single time point for sample collection. Therefore, the conceptual model is inadequate to explain the continual factors among social media users at a specific period, and it might not be able to track user behaviors over time. We advise further researchers to comprehensively conduct time-series observations of the homogeneous sample to evaluate the change from early usage to long-lasting influence. This is important, as the COVID-19 pandemic has changed how we work, study, and receive information [59]. Thus, future research should address this concern in the dissemination of environmentally friendly information.

Second, the results suggest that social media contact and social media influencers (or social norms) both contribute to a sustainable green lifestyle. Yet, there is no synergistic effect between the two. Thus, future research should go beyond the simple main effect of SMC and explore other contextual situations that may moderate the link between SMC and SGL performance. The qualitative research, perhaps, can be added as semi-structured interviews for a more in-depth exploration of “How it is” and “Why it is”. This approach might provide further insight into its underlying mechanism. Other social media communication methods commonly used for marketing commercial products [60,61] and in education [49,62] may also be useful in disseminating environmentally friendly concepts and should be included in future research. In addition, we should also take into account the online fans’ defending behavior and false information dissemination behavior in future research, as these behaviors will influence people’s perceptions and acceptance (and rejection) of ideas.

Last, this study examines social media contact in an aggregate fashion. With widely varying tools and approaches (e.g., instant messenger, video-sharing platforms, blogs, broadcasts, etc.) [12], there is potentially a need for more clarity and understanding of how agencies can leverage each of these different components for successful sustainability. Further research could compare and contrast the effectiveness of other digital communication technologies in external sourcing information and how these affect a sustainable green lifestyle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., D.K.W.C., K.K.W.H. and S.S.; Methodology, S.S.; Software, J.L. and K.K.W.H.; Validation, D.K.W.C. and K.K.W.H.; Formal analysis, J.L.; Investigation, J.L., D.K.W.C., K.K.W.H. and S.S.; Data curation, J.L.; Writing—original draft, J.L.; Writing—review & editing, D.K.W.C., K.K.W.H. and S.S.; Supervision, D.K.W.C. and S.S.; Project administration, D.K.W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Items (Modified from Ho et al. [11])

- Social Media Contact (SMC)

- SMC1:

- I usually read information and articles about sustainable issues on social media.

- SMC2:

- I usually watch sustainable-related pictures and videos on social media.

- SMC3:

- I usually listen to audio programs on social media related to sustainability topics.

- SMC4:

- I usually read advertisements and pamphlets from the government and know our sustainable policy and strategy on social media.

- SMC5:

- I usually read sustainable-related articles and pamphlets of corporations on social media and know their sustainable policy and strategy.

- SMC6:

- I initially followed the social media accounts of some green lifestyle organizations (e.g., the UN Environment Program, School Environmental Club, etc.).

- Value Co-creation (VC)

- VC1:

- I use social media to share fresh ideas and information resources.

- VC2:

- I use social media to take the time needed to discuss new ideas.

- VC3:

- I use social media to collaborate and implement new ideas.

- VC4:

- I believe I have command over the factors impacting my decision-making.

- VC5:

- When interacting with social media, I believe I can make decisions based on my personal judgment.

- VC6:

- When I participate in social media, I feel I have significant autonomy in that participation.

- Social Media Influencers (SMIs)

- SMI1.

- I think the “content quality and professionalism” shared by green lifestyle advocates are the main reasons that strongly encourage me to adopt green behaviors.

- SMI2.

- I think the “frequency and amount” of content a green lifestyle advocate shares affects whether I follow them.

- SMI3.

- I think green lifestyle advocates need to be “honest” with their audience when sharing their daily sustainable lifestyle.

- SMI4.

- I think the opinion of green lifestyle advocates is “reliable and dependable” when recommending green products.

- SMI5.

- A social green lifestyle advocate’s “background information, education level, personality traits, personal values” affect whether I like and follow them.

- Social Norms—Social Media (SNSM)

- SNSM1.

- My family shows a positive attitude toward a sustainable green lifestyle on social media.

- SNSM2.

- My friends show a positive attitude toward a sustainable green lifestyle on social media.

- SNSM3.

- My school/university often disseminates information on social media about green education effectively to increase my knowledge.

- SNSM4.

- People on social media whom I do not know have a positive attitude toward a sustainable green lifestyle.

- SNSM5.

- My community regularly posts green lifestyle information on social media.

- SNSM6.

- My living city actively promotes sustainable green lifestyles on social media.

- Social Norms—Daily Life (SND)

- SND1.

- My family has a positive attitude toward a sustainable green lifestyle.

- SND2.

- My friends have a positive attitude toward a sustainable green lifestyle.

- SND3.

- My school/university often carries out green education effectively to increase my knowledge.

- SND4.

- My community regularly posts green leaflets on bulletin boards.

- SND5.

- My living city once hosted art or industrial exhibitions on a sustainable green lifestyle.

- Sustainable Green Lifestyle (SGL)

- SGL1.

- I think reducing waste and recycling old stuff is a kind of quality and rational lifestyle.

- SGL2.

- I do not like using disposable products like plastic bags, paper cups, and chopsticks.

- SGL3.

- I like and intend to participate in some environmentally friendly activities.

- SGL4.

- I will bring my own shopping bag when I go to the supermarket and consider the environmental impact of the product when I buy it.

- SGL5.

- I think I have a deep understanding of the concept of a sustainable green lifestyle.

- SGL6.

- I think I have in-depth knowledge of how to have a sustainable green lifestyle.

References

- Urpelainen, J.; van der Graff, T. United States non-cooperation and the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, C.-H.; Chen, X.-J.; Jia, L.-Q.; Guo, X.-N.; Chen, R.-S.; Zhang, M.-S.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Wang, H.-D. Carbon peak and carbon neutrality in China: Goals, implementation path and prospects. China Geol. 2021, 4, 720–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CICC Research, CICC Global Institute. Living green: New chapter of consumption and social governance. In Guidebook to Carbon Neutrality in China; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Ho, K.K. College students’ Twitter usage and psychological well-being from the perspective of generalised trust: Comparing changes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Libr. Hi Tech 2023, 41, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Fang, G.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.; Liu, L. Impact of social media use on critical thinking ability of university students. Libr. Hi Tech 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See-To, E.W.; Ho, K.K. Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic Word-of-Mouth and trust—A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.A. Effects of social media use on climate change opinion, knowledge, and behavior. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Elsevier/Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.-H.; Chiu, D.K.W.; Ho, K.K.W.; Au, C.H. Applying social media to environmental education: Is it more impactful than traditional media? Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2020, 48, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvy Consulting. State of Influencer Marketing—Mid-Year Review. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/socialogilvy/state-of-influencer-marketing-midyear-review (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- Pittman, M.; Oeldorf-Hirsch, A.; Brannan, A. Green advertising on social media: Brand authenticity mediates the effect of different appeals on purchase intent and digital engagement. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2022, 43, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.W.; Takagi, T.; Ye, S.Y.; Au, C.H.; Chiu, D.K.W. The Use of Social Media for Engaging People with Environ-Mentally Friendly Lifestyle: A Conceptual Model. In Proceedings of the SIG Green Pre-ICIS Workshop 2018, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obar, J.; Wildman, S. Editorial: Social media definition and the governance challenge: An introduction to the special issue. Telecommun. Policy 2015, 39, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We Are Social. Digital 2022: Another Year of Bumper Growth. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2022/01/digital-2022-another-year-of-bumper-growth-2/ (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S. Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Loureiro, Y.K.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Chan, A. Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Koo, C. The use of social media in travel information search. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A. Social Media Usage: 2005–2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/ (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Johannessen, M.R.; Sæbø, Ø.; Flak, L.S. Social media as public sphere: A stakeholder perspective. Transform. Gov. People Process. Policy 2016, 10, 212–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, H. Value co-creation through social media: A case study of a start-up company. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, M.; Martinez, M.G. Social media: A tool for open innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable development–historical roots of the concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission On Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chwialkowska, A. How sustainability influencers drive green lifestyle adoption on social media: The process of green lifestyle adoption explained through the lenses of the minority influence model and social learning theory. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Librová, H. The environmentally friendly lifestyle: Simple or complicated? Sociol. Časopis 2008, 44, 1111–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, I.; Cherrier, H. Anti-consumption as part of living a sustainable lifestyle: Daily practices, contextual motivations and subjective values. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiaslis, A.; Krontalis, A.K. Green consumption behavior antecedents: Environmental concern, knowledge, and beliefs. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, A.; Ferguson, D.; Beise-Zee, R. How to go green: Unraveling green preferences of consumers. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 7, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailes, J. The New Green Consumer Guide. Simon & Schuster, Inc.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, G.M.; Kangun, N.; Grove, S.J. An examination of the conserving consumer: Implications for public policy formation in promoting conservation behavior. In Environmental Marketing; Winston, W., Mintu-Wimsatt, A.T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Explaining consumers’ willingness to be environmentally friendly. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Green consumer behavior: Determinants of curtailment and eco-innovation adoption. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.W.; So, S. Towards a smart city through household recycling and waste management: A study on the factors affecting environmental friendliness lifestyle of Guamanian. Int. J. Sustain. Real Estate Constr. Econ. 2017, 1, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilg, A.; Barr, S.; Ford, N. Green consumption or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures 2005, 37, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Kvasova, O. Antecedents and outcomes of consumer environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 1319–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoğlu, E.; Kip, S.M. Brand communication through digital influencers: Leveraging blogger engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.-G. Social media and human need satisfaction: Implications for social media marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.P.; Mortensen, C.R.; Cialdini, R.B. Bodies obliged and unbound: Differentiated response tendencies for injunctive and descriptive social norms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behaviors. Commun. Theory 2003, 13, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B. When do (and don’t) normative appeals influence sustainable consumer behaviors? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, C.; Takeuchi, T. Factors of household recycling waste reduction behavior. In Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer Research; Ha, Y.-U., Yi, Y., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2005; Volume 6, pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zareapoor, M.; Chen, Y.-C.; Shamsolmoali, P.; Xie, J. What influences news learning and sharing on mobile platforms? An analysis of multi-level informational factors. Libr. Hi Tech 2023, 41, 1395–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, C. Minority influence theory. In Handbook of Theories Psychology; Van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., Higgins, E., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 362–378. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.; West, S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Flore, S. VR what we eat: Guidelines for designing and assessing virtual environments as a persuasive technology to promote sustainability and health. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2017, 61, 1519–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, N.; Wilson, J. I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 111, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, K. Contending sustainability agencements and the future world. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society, Tempe, AZ, USA, 18–20 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Yalcinkaya, G.; Bstieler, L. Sustainability, social media driven open innovation, and new product development performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabeigi, M.; Torabi, M.; Jowkar, T. The role of personality traits and the ability to detect fake news in predicting information avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Libr. Hi Tech 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Rubalcaba, L.; Gupta, C.; Pereira, L. Social networking sites adoption among entrepreneurial librarians for globalizing startup business operations. Libr. Hi Tech 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, F.; Alidousti, S.; Naghshineh, N. Designing a branding model for academic libraries affiliated with the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology in Iran. Libr. Hi Tech 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, J. Exploring the factors influencing users’ learning and sharing behavior on social media platforms. Libr. Hi Tech 2023, 41, 1436–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).