Abstract

Risk communication plays a vital role in transmitting information about hazards and protective actions before and after disasters. While many studies have examined how risk communication and warnings influence household responses to hurricanes, fewer studies examine this from the perspective of the emergency manager. Given the rapid advancements in technology and the adoption of social media platforms, as well as the increasing prevalence of misinformation during disasters, a fresh investigation into risk communication challenges and optional strategies is needed. Therefore, this study addresses three research questions: (1) What channels do emergency managers rely upon to communicate with the public before, during, and after a disaster? (2) How do emergency managers assess and ensure the effectiveness of their messaging strategies? (3) How do emergency managers manage misinformation? The challenges experienced by emergency managers related to each of these issues are also explored. Data were gathered in July–October 2024 through interviews conducted with eleven local emergency managers located in communities along the Texas Gulf Coast. Based on the findings of a qualitative data analysis, this paper presents seven distinct risk communication challenges faced by emergency managers throughout the evacuation and return-entry processes that span the communication aspects of channels, messaging, and misinformation.

1. Introduction

The contours of today’s risk landscape look very different than twenty years ago. Climate change has amplified natural hazard risks [1]. Global mean temperatures and sea level rise have risen [2,3], contributing to extreme heat and cold events [4]. Droughts and pluvial extremes are becoming more severe and longer lasting [5], making the co-occurrence of natural hazards more common [6]. These threats collide with interdependent social, built, and natural systems, which have been increasingly shaped by recent human developments and technological advancements that often result in degraded ecosystem services and, consequently, disaster events [6,7,8,9,10]. Major disasters in the USA caused by natural hazards have risen in frequency and cost—over 150% and 250%, respectively—when comparing the 20 years from 2003 to 2022 to the previous 20-year period of 1983 to 2022 [11]. At the same time, the information environment surrounding the communication of hazard and disaster information has been significantly altered by digital technologies and public preferences for the use of social media for news [12]. The “infodemic” that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic created pathways for the overabundance of information and the spread of misinformation [13,14,15,16]. Flooded with contradictory information, confidence in authorities was eroded for many. Today, in addition to misinformation and a heavy reliance on social media, there is a widespread loss of trust in information authorities [14,15,16,17,18].

Years of disaster research have established that risk communication is a key component in understanding the immediate protective action decisions (e.g., evacuation and shelter in place) people make when facing various hazards, e.g., [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Despite the importance of communication in impacting evacuation and sheltering decisions, few empirical studies examine people’s reliance, perceptions, and preferences of information throughout both the evacuation and return-entry processes. Additionally, less is known about the preferences and perceptions emergency managers have related to the use of various information channels, as well as the challenges they experience in communicating risks and warnings during these critical points in time. Modern technological advancements in warning channels, social media, and communication technology, coupled with evolving information channel preferences and declining trust in information sources, necessitate a fresh investigation into optional risk communication strategies.

In addition to evolving technology and warning channel preferences, the prevalence of misinformation also poses significant challenges for both emergency managers and the public. The abundance of shared information, both official and unofficial, through social media channels, often results in individuals being increasingly exposed to misinformation. Recent studies suggest that misinformation related to health and natural hazard emergencies is interpreted by some of the public as a reason not to comply with safety recommendations [27,28]. Countering misinformation poses a challenge for emergency management officials, because there may not be resources after a disaster to devote to monitoring and responding to misinformation [29]. Additionally, it may be difficult to combat misinformation, especially as risks and protective action recommendations may evolve over time as the event progresses and new information, risks, and hazards arise.

Given the rapid advancement and evolving reliance on various communication technologies and channels, as well as the emergency management challenges that arise due to the circulation of misinformation, there is a need to revisit existing risk communication frameworks. In particular, an examination of these issues from the perspective of the emergency manager is warranted. To address the problem posed to risk communication by a rapid increase in channels and the prevalence of misinformation, this study addresses three primary research questions: (1) What channels do emergency managers rely upon to communicate with the public before, during, and after a disaster? (2) How do emergency managers assess and ensure the effectiveness of their messaging strategies? (3) How do emergency managers manage misinformation? We are also interested in understanding the challenges experienced by emergency managers related to each of these issues. This study uses qualitative methods of analysis to answer these questions using data collected through interviews with emergency managers in coastal Texas. We find seven distinct challenges for risk communication in today’s digital era that span the communication components of channels, messaging, and misinformation.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of risk communication, as a function of emergency management, aimed at keeping people safe from hazard risks [30]. It is a global priority, articulated in the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, to ensure cities are safe and resilient to disasters [31]. This study supports sustainability by highlighting the importance of refreshing risk communication in today’s information era, so that vulnerable populations are protected from the impacts of disasters.

2. Background

2.1. Risk Communication and Protective Action Decision Frameworks

For over 60 years, the communication of hazards and risks to the public has been a significant theme in the disaster science literature. The Warning Process Framework (WPF) was first introduced by McLuckie [32], who conceptualized the process undertaken by emergency management and local officials. McLuckie suggests that a warning should be viewed as a process and is the product of a risk assessment system. Thus, the WPF for emergency management comprises three stages: (1) the collection, collation, and evaluation of risk information data; (2) the decision to issue a warning and the creation and dissemination of warning messages; and (3) monitoring the public’s responses to warnings [32]. He notes that this process resets itself as the nature of the risk changes, or if there is a need to update the messages, based on the public’s response to the risk and warning message. Quarantelli [33] later expanded on the WPF, proposing that the first phase of assessment, involving the detection of hazard risks and the evaluation of the likelihood of hazard agents occurring, is the most robust aspect of the warning system, while the dissemination phase was perhaps the least effective part of the process (at the time of the report). The response phase, then, refers to the adjustment behaviors people take after receiving hazard warning messages and the subsequent actions undertaken by emergency managers to update warnings as the hazards evolve.

The Model for the Determinants and Consequences of Public Warning Response (hereafter referred to as the Warning Response Model (WRM)) and the Protective Action Decision Model (PADM) also emphasize dissemination issues [34,35,36]. Both WRM and PADM consider the receivers’ internal processes, since they mediate the relationship between warning dissemination and responses. These models highlight the process of understanding, believing, and personalizing risk information [34,36].

The dissemination stage’s focus is slightly different in the WRM and the PADM. In the WRM, it is defined as the sender factors. It focuses on constructing warning messages, including specificity about the impact location, protective actions, the time of impact, and the characteristics or risks. It also emphasizes the consistency of risk information. Research shows that warnings are more effective when they emphasize specific protective actions over simply conveying risk [37,38]. The WRM has also been used in studies focused on the composition of warning messages and how different types of messages can effectively encourage appropriate response actions [37,39,40,41].

On the other hand, the PADM focuses more on how risk information is disseminated. It includes environmental cues, social cues, information sources, information channels, and warning messages; the dissemination process can also be affected by the receivers’ characteristics and the social/environmental context [34]. Studies have suggested that different types of disaster events rely on different cues, sources, and channels. For example, earthquake studies generally find that people tend to rely more on environmental and social cues when deciding on protective actions, especially in a place where an earthquake early warning is not available [21,35,42]. Therefore, emergency managers’ risk communication should focus on helping people understand the situation and suggesting protective actions that reduce the risks following the main earthquake, such as aftershocks or fire hazards [43,44]. On the other hand, dissemination strategies for meteorological disasters such as hurricanes are generally quite different from those for earthquakes, as they typically come with some forewarning time, ranging from hours to days, depending on the type of hazard. For example, emergency managers usually have days to disseminate and update warning information in the case of hurricanes. Information shared with the public often includes maps of the storm surge risk zones and the expected path of the storm, the expected impacts of the storm, and information on how to prepare to evacuate or shelter. Studies have shown that the source and channel of hurricane risk information people seek varies by individual and social/environmental context [34].

Studies on hurricane evacuations have found notable differences in how various demographic groups seek risk information. Older adults are less likely to seek hurricane risk information from their peers or observe environmental cues; women are more likely to seek information from local authorities, peers, official warning messages, and both social and environmental cues; white individuals are less likely to rely on local authorities, peers, official warnings, or social cues for risk information; married couples tend to seek information less from social cues; individuals with higher socioeconomic status (education and/or income) are less likely to rely on peers or social/environmental cues; and, homeowners are less likely to seek official warnings and social cues [45,46,47]. Regarding hurricane evacuation decisions before hurricanes, studies have found that most sources of risk information positively contribute to the decision to evacuate. Social cues and official watch messages, including evacuation recommendations, contribute most to evacuation decisions [20,22].

Previous research demonstrates that as a hurricane disaster progresses from the pre- to the post-event phase, the information needs of emergency managers and the public change. Whereas information in the pre-event phases focuses on variables such as forecasts, expected impacts, and communicating protective action recommendations, information in the post-event phase often centers on the impacts of the disaster and emergence of secondary hazards, the status of lifelines and community services, and the communication of the all-clear message or other return strategies such as full-scale returns, look-and-leave plans, and phased returns [48]. A lot of these information needs are also sought by evacuees awaiting issues of the all-clear message or return plan [24]. From the perspective of the emergency manager, gathering information and maintaining effective communication with evacuees and residents within a disaster-impacted area is challenging. In the aftermath of a hurricane, communicating risks and return strategies to an evacuated population can be difficult, as residents are often widely dispersed throughout the region.

Evacuees may not have access to the same information sources utilized when making their evacuation decision, and challenges can arise when emergency management organizations lack contact information that would allow them to transmit information directly to the evacuee [49]. This often leads to individuals not receiving communication about return strategies. For example, following Hurricane Ike in 2018, only about 1 in 3 (36%) evacuees surveyed after the storm indicated that they were aware of their community’s return plan [50]. Prolonged power outages and significant damage to communication infrastructure can also limit the emergency management office’s ability to gather information about damage in their community and the status, timing, and expected restoration of utilities as well as other updates from regional and state entities that are necessary to prepare for the return movement. Additionally, studies have found that a lack of adequate staffing to monitor social media and control rumors related to community damage, the prevalence of looting, and return plans (e.g., saying it is okay to return when it is not) can defer time, effort, and resources away from more pressing needs that arise during the response and early recovery phases [29,49].

Regarding evacuees’ behavior related to hurricane re-entry risk information, studies show that individuals with children are more likely to seek re-entry information from local news in their hometown and national news. In contrast, those with higher levels of education are less likely to obtain re-entry information from national news or local news in their evacuation destination [47,50]. Thus, in general, people rely on various channels for information before, during, and after disasters [22,50,51,52]. The channels that households rely upon during the evacuation phase may not be as accessible while evacuated, therefore forcing evacuated households to seek out alternative channels and sources for information as they transition through the pre-event warning and return-entry processes [47]. Over the past two decades, these channels increasingly include information disseminated via official emergency management websites and social media outlets, along with local and national news outlets, television stations, and radios as well as information shared by relatives, neighbors, and peers, including on social media. Lindell [34] observes that preferences in warning channels have evolved over time, with a greater reliance on the internet and social media for gathering and seeking information than in the previous two decades.

Emergency managers and local officials utilize numerous channels and information strategies to formulate and disseminate protective action recommendations [29,53,54]. While these studies offer important insights into the channels utilized by emergency management and local officials during hurricanes, less is understood about the preferences of information sources and channels utilized by households and, more specifically, the extent to which the preferred information channels of households align with those utilized by local emergency managers. Furthermore, with the evolution of existing communication technologies and the emergence of new communication platforms, new challenges arise. An improved understanding of the contemporary emergency manager’s perspective and their experience managing information and communicating risks is needed to fully promote sustainability by safeguarding communities and protecting vulnerable populations.

2.2. Misinformation Challenges for Risk Communication in the Digital Age

Misinformation refers to false or inaccurate information created without the intention of causing harm; however, when people believe it to be true, it can mislead them and cause harm to individuals or society as a whole [55,56,57,58]. Disinformation and malinformation are often considered related concepts to misinformation, but they have distinct characteristics. Unlike misinformation, disinformation is intentionally created to mislead or harm individuals, organizations, or society [56,59]. On the other hand, malinformation involves real, factual information that is used in ways that cause harm. While misinformation involves false information and disinformation involves deliberate falsehoods, malinformation takes accurate information and manipulates it for harmful purposes [57,58,60].

Misinformation has often been the most widespread form of false information during disasters, especially when compared to disinformation or malinformation, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic [61,62]. However, combating misinformation is not easy, particularly during disasters like hurricanes, which have a relatively long forewarning time (2–5 days). Emergency managers frequently face the challenge of differentiating between real information and misinformation during such events.

Misinformation is a fixture in today’s digital age. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok have emerged as major sources of news and information for many people [12,16]. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey reports that half of all U.S. adults at least sometimes get news from social media [12]. Due to methods of engagement (e.g., retweets and likes) [63], the use of artificial intelligence to maximize views [64], and the use of generative artificial intelligence to create and modify text and images [65], misinformation is amplified on social media [63]. A study of TikTok—the social media site with the most recent growth in users and where one-third of social media users get news—found that 1 in 5 news-related clips contain misinformation [66].

Furthermore, algorithms used by social media platforms and search engines often personalize content based on users’ preferences and behaviors, creating filter bubbles and echo chambers [67]. A recent study found that about 25% of American adults consistently stay in an information ‘bubble’ that aligns with their existing beliefs and attitudes [16]. Following tendencies known as “confirmation bias” and “motivated reasoning”, people are prone to seek out information that supports their existing beliefs while ignoring and criticizing information that does not [68,69]. This can lead to the reinforcement of existing beliefs and the polarization of viewpoints [70]. Sorting through conflicting information sources has become a challenge, impacting how individuals perceive and respond to various risks [71] and how emergency management agencies effectively communicate risks [71,72,73,74,75].

These trends present considerable challenges for risk communication, as misinformation and reliance on social media for news are not without consequences. Among those who rely on social media for news, concern about inaccurate information is lower than among other adults; knowledge of current events is worse; and, within the context of COVID-19, compliance with health guidance has been poorer [16]. Similarly, siloed information-seeking among conservatives has been linked to non-compliance with COVID-19 recommendations and mandates [27]. Behaviors in reaction to natural hazards are affected as well.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in Houston in 2017, misinformation spread on Twitter that officials were checking identifications in public shelters, which led undocumented individuals to remain indoors, posing severe risks to their safety [76]. Studies have also found that the exposure time to a disaster, source of information, information-seeking behavior, social media use, and risk or previous experience or exposure to disasters are critical factors in determining how the public processes misinformation during disasters [76,77]. The longer people are exposed to a disaster without adequate information, the more likely they are to believe whatever is circulated on social media. While these studies demonstrate the challenges posed by misinformation for risk communication, current disaster response models and theories have not accounted for this. To fill this gap, we focus on misinformation and related issues in risk communication posed by today’s information environment. The next section discusses our methodology, followed by an analysis of the findings from interviews with emergency managers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

To explore the risk communication of evacuation and return-entry messages in today’s information environment, we focus on the hazard–threat of hurricanes in coastal Texas. We selected hurricanes as a point of focus because these events usually offer sufficient forewarning time for risk information to circulate before the event as well as a period after the hurricane for re-entry information to be communicated. We selected the Texas coast because its geography, sociodemographic diversity, and vulnerability to hurricanes make it an ideal location to perform this study. On average, the Texas coast is hit by a hurricane every six years [78]. Since the year 2000, ten tropical storm events have impacted the Texas Gulf Coast, resulting in beach erosion, flooding, wind damage, storm surge, fatalities, and the destruction of property and infrastructure, totaling over USD 100 billion in damages [78,79,80,81]. The last major hurricane to hit Texas was Hurricane Harvey in 2017. As a Category 4 storm, Harvey caused an estimated USD 125 billion in damages, ranking it the second costliest hurricane (behind Hurricane Katrina) [79,82,83,84]. Harvey also set records as one of the wettest Atlantic hurricanes on record, dumping 27 trillion gallons of water over Texas (TDEM, n.d.). Harvey is regarded as a beacon for future storms, as warmer oceans and sea-level rises will contribute to conditions ripe for wetter and more intense tropical storms [85].

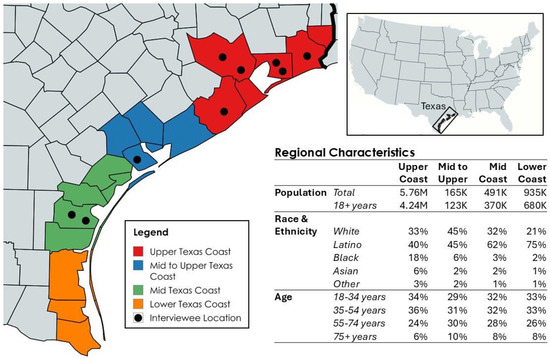

Along the Texas coast, 18 counties were targeted for this study, forming four regions: the Upper Texas Coast (Orange, Jefferson, Chambers, Harris, Galveston, and Brazoria Counties); the Mid to Upper Texas Coast (Matagorda, Jackson, Victoria, and Calhoun Counties); the Mid Texas Coast (Aransas, Refugio, San Patricio, Nueces, and Kleberg Counties); and the Lower Texas Coast (Kenedy, Willacy, and Cameron Counties) (see Figure 1). The Upper Coast region is the largest of the four regions, with a population size of 5.76 million residents, whereas the Mid to Upper Coast region is the smallest, with only 165,000 residents [86]. Within the four regions, there is a range of local jurisdictions from the City of Houston, the fourth most populous city in the USA, with a population of 2.3 million people, to Kenedy County, which has a population of 358 persons. In terms of the racial and ethnic composition of the study area, minority groups are the majority of the population in all four regions. Notably, Latinos comprise 62% and 75% of the Mid Coast and Lower Coast regions, respectively. There is also variation in terms of adult age groups. The Mid to Upper Coast region has the largest proportion of older adults, with 40% being 55 years or older, while the Upper Coast region has the largest proportion of young adults, with 70% between the ages of 18 to 54 years. This diversity of the study area should enhance the generalizability of the findings, as emergency managers from these different regions must tailor their risk communication to different audiences.

Figure 1.

Study area map and sociodemographic characteristics [86].

3.2. Data Collection

In the United States, emergency managers assume a range of responsibilities aimed to ensure communities are able to mitigate, prepare, respond, and recover from disasters. Individuals with this job title may work for local, state, or federal agencies; the private sector; or the nonprofit sector. Critical to this profession is the ability to identify, assess, and effectively manage hazards, as well as communicate risks and protective action recommendations to the public and to key stakeholders [87]. In hurricane-prone areas in particular, emergency managers often assume responsibilities to identify areas at risk to the hazard, creating and disseminating evacuation warnings and communicating the protective actions citizens need to undertake when evacuating or sheltering. After an event, they often oversee damage assessments, coordinate the deployment of resources to disaster-impacted areas, gather and share information with the public, and assist with the creation and execution of return-entry strategies [48,49].

Because we are interested in a fresh investigation into risk communication in today’s misinformation age, semi-structured interviews were carried out with emergency management professionals responsible for communicating hurricane messaging pre- and post-event. This is an appropriate methodology for unexplored areas of research [88]. Emergency management professionals at the city and county levels across the study area were contacted through publicly available information and invited to participate. The interviews aimed to capture participants’ best practices and preferences in risk communication. Interview questions focused on communication channels, message content, past experiences with disasters, and the management of misinformation. The questions addressed both pre-event (hurricane warnings and evacuation orders) and post-event (return-entry phase) scenarios, examining how communication strategies and challenges evolved across these stages.

The interview protocol and questions were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Texas A&M University and the University of North Texas. The interviews, which lasted approximately 20–45 min, took place between July and October 2024. In total, eleven emergency managers from nine jurisdictions were interviewed (see Figure 1), yielding approximately 261 min of commentary. All regions except for the Lower Texas Coast are represented in the interviews. Participation may have been negatively affected by the timing of interviews during an active hurricane season, with the landfall of Hurricane Beryl on the Mid to Upper Texas Coast on 8 July 2024. While the initial interest in project participation was high, communications from potential interviewees waned after the event, likely due to the prioritization of response and recovery from the storm.

3.3. Method of Analysis

We analyzed the interview transcripts for emergent themes following qualitative analysis standards [89,90]. This involved dividing the interview transcripts into pieces, largely based on the questions asked but also on the flow of the discussion. In line with guidance from qualitative researchers, we made sure these pieces were large “chunks” to retain their context and to avoid the risk of pulling out sound bites that misconstrue the interviewee’s meaning [90]. Then, we reviewed each chunk, abstracting themes based on our knowledge of today’s information environment and prevailing theories of risk communication and protective action. The findings in the next section are organized by the predominant themes identified in the interview data.

4. Results

We posed three research questions that touch upon channels of communication, the effectiveness of messaging, and managing misinformation. We are interested in understanding emergency managers’ preferences and experiences with these aspects of risk communication and, critically, the related challenges that they have encountered. In all, we identified seven core challenges of risk communication in today’s digital era across the communication aspects of channels, messaging, and misinformation (Table 1). We will discuss each in turn as we consider the research questions posed.

Table 1.

Themes identifying challenges for risk communication.

4.1. Communication Channels

We begin by exploring Research Question 1: What channels do emergency managers rely upon to communicate with the public before, during, and after a disaster, and what challenges have they experienced related to this? The emergency managers we interviewed were keenly aware of the myriad of communication channels, particularly those available via digital technologies and social media, available in today’s information environment. In addition to traditional channels, including official mass alert systems, televisions, and radios, social media was routinely cited as a platform used by emergency managers to distribute emergency warnings and receive feedback from citizens. Interviewees mentioned the use of Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly known as Twitter). Smaller jurisdictions typically cited using fewer social media platforms due to the limited manpower to manage accounts, while larger jurisdictions rely on their public information officers [91] to manage and push out warnings on multiple social media accounts. Facebook, in particular, is in widespread use by those we interviewed.

Most interviewees indicated that they use the same channels before, during, and after an emergency or disaster event. One interviewee [92] commented that there is no preference by the emergency management office for one channel over another during specific phases of the event, rather:

…We do everything we can to make sure that we’re utilizing all the channels, that we are—when we’re putting together our messaging, that we’re taking all of the recipients into consideration, whether it’s English as a second language, some of our functional needs communities that may have communication, things that are in front of us. If it’s the elderly, if it’s businesses, whoever it may be, we try to make sure that we do everything that we can, cover the spectrum as much as possible.

However, another interviewee [93] noted it is critical to be nimble following an emergency or disaster in terms of communication channels. Reflecting on a recent major disaster, this emergency manager noted that digital channels lost connectivity after 24 h. This required a considerable shift in the way information was distributed, from webpages, social media, and cellular phone applications to paper. The situation was described as, “First responders, sheriffs, constables, fire guys, literally handing out flyers to pass out some information. It’s about as inefficient as it gets. But at the end of the day, you’ve got a…big chief tablet and a purple crayon, and you do what you can”.

4.1.1. Challenge 1: Channel Preferences of Risk Information Receivers Are Not Well Known

Interviewees noted that given the wide array of communication channels available today, it is difficult to know which ones to target. The use of social media, in general, was seen by interviewees as an effective platform. One interviewee [94] noted that it is “probably our quickest and fastest way to get that information to our residents”. Despite this, the diversity and quantity of communication channels are challenging for risk communicators. While it is recognized that people have preferred channels, it is not clear what those channels are, because, as one interviewee [91] put it, “not everybody uses the same thing”. Another emergency manager [95] commented on differences across age groups, saying the following:

I know that the older people and myself, we’re on the Facebooks. But I do know that the younger generation—I have a 23-year-old. They tell me, “That’s not how we get our information. We do it differently”. Most of them don’t even watch the news anymore. So it’s like, “How do I get to you”?

Additionally, interviewees [96] noted that knowing which channels are best to reach people post-disaster is challenging. One emergency manager [92] said they adjust following an event to communicate more via television news channels in the places where people have evacuated to and, importantly, leverage that news coverage to educate the public on where (e.g., which channels) to find information about returning home.

4.1.2. Challenge 2: Selecting the “Right” Channels for Communication in Emergencies (Versus More Severe Disasters) Is Difficult

The choice of channel can also be difficult, because emergency managers must communicate risks about incidents that vary on a spectrum of severity, from minor emergencies to life-threatening hazards. The use of some channels, including official warning and alert systems, signal to recipients that the information is critical, and the situation is of higher risk, regardless of the content of the message. Yet, overuse of such channels may desensitize people to risks. Without broader variations in methods to inform the public about daily emergencies (e.g., major highway incidents) and imminent threats (e.g., hurricanes), relying on a single type of channel to disseminate all risk information could reduce the public’s attentiveness to major disaster events due to information fatigue. On this, one interviewee [96] described the following:

Unless it’s a declared disaster like a hurricane, in that situation, we’re going to be using our warning and alert systems. But smaller incidents, I think, have been a little bit more of a challenge. And how do you switch between what you’re using on a normal day-to-day basis to your warning and alert system?

4.1.3. Challenge 3: Avoid Too Many Messages or People May “Tune Out” of Emergency Management Channels of Communication

The emergency managers we interviewed were very aware that people select what channels of communication they engage in and can simply “tune out” when it no longer suits them. One interviewee [96] described it this way:

We live in an information age, and people can click on and click off something or uninstall your app or whatever it might be. So, we try to balance the need of when we actually need to use this in a real emergency. So, when we do use it, people are paying attention to it as opposed to bombarding them on a daily basis with this platform.

Another interviewee [93] asserted that people are already tuning out, stating the following:

I think we’ve overcommunicated risks for the last several years…I think we’re too willing to call something a disaster as opposed to just an incident. I think we’ve made what should be sometimes localized incidents bigger deals than they should be. So I think in that sense, I think that may be part of the reason why people are tuning out some of the preparedness messaging.

4.2. Effectiveness of Messaging

Next, we evaluate Research Question 2: How do emergency managers assess and ensure the effectiveness of their messaging strategies, and what challenges have they experienced related to this? Participants in this study described effectiveness in two different ways: (1) how many people received the official message and (2) if the receivers of the message understood the content and acted upon it (e.g., took the recommended protective action). Interviewees [97,98] indicated that they use the metrics available on the communication platform to gauge the uptake of information. On mass warning systems, this includes the number of people who received the message. On social media, this involves reactions such as likes and shares. Reflecting on recent events, one emergency manager [94] we interviewed said the following:

[W]e know that Facebook did really well during our disaster situations. And so we were able to pull those analytics and see that that post got almost a million hits or whatever. So yeah, we were able to see that and to know what platform was doing the best as far as getting disaster information or crisis communication out.

But another interviewee [99] pointed out the downside of relying on social media metrics, saying, “…unless you get a lot of likes or comments, you really don’t know how many people are receiving that. And a lot of the times, people, unless they’re angry about something, they don’t tend to engage”.

Challenge 4: There Are Limited Resources and Methods for Assessing the Effectiveness of Messaging

Interviewees of larger jurisdictions cited relying on their public information officer and/or department for an assessment of messaging. However, smaller and more resource-constrained jurisdictions indicated that they struggle to gauge the effectiveness of messages. One emergency manager [99] commented that social media metrics are not useful, because they do not have much engagement by the public on their posts. Another said [95], “We just don’t have the funds for a lot of stuff to do, which if I had a communications department, that’s what I would be doing, is having them do surveys for me and finding out how people want to hear information, what’s the best way to get it to them”. Further, many interviewees noted that it is difficult to know by commonly used metrics (e.g., number of likes) if the message affected behaviors. One interviewee [99] posed the dilemma in two parts, asking, “On the one hand, [do] they understand what they’re supposed to do, and then did they actually do it”? Another emergency manager [92] put it this way, “[W]hat exactly is it you need to hear from us to make you react in the way that we need you to react? Because I’m out of ideas on that”.

4.3. Misinformation and Related Risk Communication Challenges

Finally, we explore Research Question 3: How do emergency managers manage misinformation, and what challenges have they experienced related to this? Misinformation spread on social media is now something risk communicators must actively manage. As one interviewee [95] put it, “There’s always a risk of misinformation. And as fast as things travel now, sometimes it gets away from you”. The control of messaging is simply more difficult, given the high accessibility of digital technologies and artificial intelligence. On this, an interviewee [93] commented, “It’s not enough that we put something as a credible source on a social media site. Somebody who is clever with AI can do something that totally changes that message”. When misinformation is spread, it can have serious consequences during disasters, such as causing “limited resources and response apparatus to be deployed to things when there actually aren’t emergencies there” [96]. Many times, the limited resource expended is manpower in responding to misinformation, even hoaxes. For example, one emergency manager [97] shared the following:

One of the funniest ones was back during Hurricane Harvey. Most of the city here was underwater. Somebody had Photoshopped some sand sharks swimming down the road or something. It’s like, ‘No, people. There’s not any sharks swimming down the boulevards…That’s not true’. ‘Well, I saw the pictures. It has to be true. I saw the picture’.

Beyond hoaxes, much of the misinformation that emerges during an emergency or disaster involves unintentional inaccuracies. One interviewee [96] gave an example of concerned family members from out of state posting third-hand inaccurate information on social media (e.g., “I heard someone was flooding on your street”). However, this inaccurate information quickly spreads, because it is shared on social media.

Similarly, people may tune into the wrong information and then spread it among their social networks. Another interviewee [99] described that many residents of their community, which is a small municipality adjacent to a larger metroplex, pay attention to information that pertains to the nearby city—“it’s not really misinformation, but it may be information that’s not specific to us”. This becomes a challenge, because the information may not guide appropriate action for the residents of the smaller community.

4.3.1. Challenge 5: It Is Unclear How to Help People Cut Through the “Noise” in Today’s Information Environment

The number, diversity, and open access of communication channels or platforms create noise that people have to sort through to get accurate information. As one interviewee [96] put it, “I would say, over the last probably four to eight years, it’s been a little bit more challenging in controlling messaging because there’s just so much—there’s so many other sources that people are paying attention to…I think that’s always the biggest challenge, is how you break through this noise that’s already out there”.

The noise in today’s information environment is largely due to the fact that digital technology has enabled anyone to have a voice on any issue—including emergencies and disasters. This increase in the number of channels used to create and share information (or misinformation) results in a significantly high volume of information that end-users have to navigate. On this, one interviewee [96] noted, “Everyone becomes a meteorologist during the storm” and they purport themselves as “experts on what’s happening in your community”. The challenge for risk communicators [96] becomes how to “steer people back to the Weather Service or…even your local meteorologists as opposed to some guy that lives in Canada that’s on YouTube telling you what their interpretation of the latest models are”. Another interviewee [100] elaborated on this, stating the following:

…as good as social media can be, if it’s used in a positive way, there’s also the whole negative effect of there’s someone out there that thinks they’re the expert. And so they’re trying to provide guidance, and it may just be wrong guidance. And is it due to them not being educated in emergency management, understanding the whole picture.

It is not only residents who need help sorting through the noise created in today’s information age. Interviewees pointed out that decision makers, too, need guidance in “getting the information they need to make good, sound decisions” [96].

4.3.2. Challenge 6: You Need Multiple Strategies to Manage Misinformation

To manage misinformation, the emergency managers we interviewed cited multiple strategies for managing misinformation. The most fundamental is to clarify inaccuracies and point people to credible authorities and information. Summed up, the approach is simple, you say the following: “This is wrong. This is really what’s going on. This is the place you go to get the most accurate information” [95]. This approach, however, may have to be repeated. One interviewee [97] lamented, “Once the rumor mill starts, there’s almost nothing you can do about it except stick to that same consistent message and…keep putting out the right information”.

Another interviewee [96] warned that it is important to not engage inaccurate information on social media when correcting it, stating the following:

[W]hat we’ve learned from that is if you want to counter a message, you just make sure that you reissue a statement with your accurate information entirely separate from the other statement that might have been the cause of the problem. So that way, your information gets shared separate and apart from the false information because it’s just kind of propagating itself based on our information. So, in other words, don’t just reply or share something. Completely have a separate official authoritative-source statement to recant or rebuttal whatever the false story is.

Other interviewees [95,101] pointed to consistent messaging, internally—within local government—and externally—with other organizations and regional industries—as important for managing misinformation. This requires collaboration to, as the interviewee [95] put it, “make sure we’re all speaking the same battle rhythm, the same…singular message”. It also requires, as another interviewee [96] put it, “building relationships with the community and making sure you have key partners that can then go and amplify your message”. This interviewee continued with the following:

[T]he municipality, the jurisdiction as a whole, can’t do it alone, and you need those other sounding boards to share your messaging and to be the amplifier for you. And I think that’s key—is knowing your community, building those inroads of who your ambassadors are, really, that are going to share your messaging.

Still, another emergency manager [93] pointed to transparency as being key to combating misinformation, because “disasters are not scripted” and “things are going to change from one day to the next”. This interviewee continued, saying the following:

[Y]ou have to be extra clear in explaining what the change is, why the change is, and what the impacts are. So really, I think for us, it’s kind of just driving us back to some basics of making sure, (A) we’re as authoritative as we can be, and (B) that when there is a change, we explain it in a way that’s understandable. It doesn’t sound like we’re just kicking it under the rug. I think you have to be open about it and transparent”.

4.3.3. Challenge 7: There Is a Need to Refresh Risk Communication in Today’s Information Environment

Beyond correcting inaccuracies and being transparent, one interviewee [93] asserted that to truly combat the spread of misinformation today, there is a need to refresh risk communication, stating the following:

[W]e’ve been saying the same thing since 2001, “Get a kit. Make a plan. Stay informed. Be involved”. Well, that’s great. It actually is good advice. It tells you exactly what we need you to do, but I don’t think people are hearing it anymore. I think it’s become stale. As I said, it’s like the preacher’s in the pulpit. The sermon’s now been the same for 20 years, and everyone’s tuned out.

Part of refreshing risk messaging may entail changing the way we talk about hazards, particularly co-occurring hazards such as wind, storm surge, and flooding. Commenting on the misnomer of hurricane storm categories, which are based on wind speed, one interviewee [96] noted the following:

[W]e need to be more focused on what the actual risks are of that hurricane and not just focused on one aspect of it. And I think that’s our greatest challenge. And so we try to put the information out there and we focus on what actually is the threat. Is it tidal surge? Is it coastal storm surge? Is it the rainfall that we’re worried about on this?…The category size is not really a good indicator of what the risks that are brought with this storm.

Another aspect of refreshing risk messaging entails the consideration of social anxiety and stress, as these have become more acute since the COVID-19 pandemic. On this, one emergency manager [92] emphasized that risk communicators should not rely on fear to motivate action. Rather, in crafting risk warnings, they should ask, “[I]s there anything we can be doing or adjusting that might help minimize the stress that communities might be having”?

Refreshing risk messaging today was brought up by interviewees as needed to accurately communicate risk, reduce stress, and stymie misinformation. Relatedly, this may encourage renewed credibility of government risk messages. Some interviewees commented on this, with one emergency manager [92] stating, “the openness and the acceptance of government messaging doesn’t seem to be what it was when I first started here [15 years ago]”. This individual elaborated, saying the following:

So people are less likely to take our word for something. And I said that was something that kind of—it’s always kind of been there. COVID made it worse because the warnings were constant. And it was almost—having participated in this and also been a victim of it in some ways, it didn’t matter what you did; you were going to get COVID. And that’s one of the warnings. We were warning people not to do anything. “You don’t want to get COVID, so don’t do this. Don’t do that”. It was, “You can play golf, but not tennis”. It got into the minutiae of what was safe or not safe. I think that kind of hurt us in a credibility way as government, not necessarily our office, but I think across the board.

5. Discussion

This study offers an updated perspective on the challenges local emergency managers experience when communicating risks before, during, and after hurricanes. The findings highlight the challenges emergency managers and message recipients encounter related to the significant volume of information created and shared from both official and unofficial sources. The traditional channels for warnings, such as official mass alert systems transmitted via televisions, radios, and door-to-door notifications, now include a growing number of internet channels and social media platforms—and channel preferences of subgroups of the public are not fully known, as illustrated by Challenge 1. This aligns with Lindell’s [34] observation that preferences among households in warning channels have evolved over time and that studies indicate there is an increased reliance on the internet and social media for gathering and seeking out information among households [20,102]. It is reasonable to expect that this trend will continue as social media platforms evolve, and different groups gravitate toward different venues for posting, seeking, and sharing information. This poses a challenge for emergency management agencies, as they will need to ensure that their offices are utilizing social media platforms in ways that reach intended audiences.

Relatedly, emergency management and public information offices must juggle how to select communication channels that resonate with recipients so that they do not tune out. This is especially important, as suggested by Sutton and colleagues [103], where residents turn to their “backchannel” (i.e., peer to peer and informal channels) for risk information. As Challenge 2 highlighted, this involves the selection of the “right” channels for more minor emergencies and reserving official warning systems for higher-risk events. By avoiding over- or poor messaging, the expectation, as discussed in Challenge 3, is that people will be less inclined to “unsubscribe” or opt out of the channel. This requires thoughtful communication protocols, particularly for minor emergencies and preparedness campaigns. Because people engage in social media not only for information seeking but also for connection, emergency management communication protocols during “blue skies” should consider multidirectional communication that intentionally interacts with residents [104]. This may boost the channels preferred by emergency management and, by engaging with people, discourage tuning out.

Beyond tuning out, the expanding options of information channels also create the difficulties described by emergency managers in Challenge 5, which includes an abundance of information that must be verified by the recipients of risk communication and warnings. Previous studies have found that individuals often find it difficult to identify misinformation in Tweets, and as a result, they may share rumors without realizing the information they are sharing is not accurate [105]. More than ever before, households have a high volume of information to entertain as they progress through the protective action decision process [106]. Additionally, not all the information created and shared by unofficial sources and channels is accurate, and misinformation—whether introduced intentionally or unintentionally—can result in confusion and, ultimately, the selection of sub-optimal protective actions during disasters.

Even if emergency managers are utilizing information channels that effectively disseminate warning messages, the availability of those channels may be limited after a disaster. This provides a unique challenge for emergency managers in the aftermath of an event in terms of determining how to ensure that the information they provide reaches evacuated groups and individuals who remain in the disaster-impacted area. As Manandhar and Siebeneck [49] found, when communication infrastructure and technologies fail during a disaster, emergency managers need to adapt and provide alternative forms of communication. After Superstorm Sandy in 2012, one participant described going back to a pencil and paper and posting on community bulletin boards in order to share information with the public. Identifying a variety of potential channels that can be used to communicate with residents after a disaster may improve public awareness of the various ways information can be transmitted while also helping receivers to “cut through the noise”. People may be less likely to seek out information as a means of filling the void of a lack of available official information if they know where the information can be accessed.

Another theme that emerged from the interviews was the recognition of the need to manage misinformation. Previous studies highlight the negative consequences that can stem from the spread of misinformation, such as physical harm, a decrease in well-being, an increase in stress and anxiety, and undertaking sub-optimal protective actions that fail to effectively minimize exposure and risk to the hazard [107]. In the aftermath of an event, the spread of misinformation about damage and accessibility to the disaster-impacted area can result in residents returning too early, thus creating additional challenges for emergency managers [49]. While all of the interviewees recognized the need to address misinformation while managing hurricane events, there were different perspectives on how to best address this challenge.

Challenge 6 offers some insights into the strategies that emergency managers undertake to address misinformation. Ensuring that they are putting out accurate information that corrects the misinformation is a priority, as is leveraging their relationships with other local officials and media to ensure that accurate information is repeated and consistent across multiple sources and channels. The need to provide consistent information across different sources is a strategy that has been identified in previous studies as being one essential element to increasing the likelihood that residents receive the correct information needed to make appropriate protective action decisions [74,107]. Additionally, as noted by one interviewee [93], ensuring that the message and information are clear, understandable, and available is a return “to the basics” and is essential in optimizing risk communication.

Challenge 7 calls for a refreshing of risk communication strategies undertaken in emergency management. Given the escalation of natural hazards due to climate change and the greater frequency of co-occurring or compounding hazard events [1,6], communication about risks, as the interviewees noted, needs to evolve beyond preparedness kits and storm categories. To do so requires that we know more about risk communication preferences among subgroups of the public and explore the effectiveness of varying messages, a need iterated by interviewees in Challenge 4. For example, a recent study found that using visuals and specific types of framing can boost risk messaging on social media [104]. Future research should further explore the issue of message effectiveness, connecting it to existing theoretical frameworks of risk communication.

5.1. Implications for Risk Communication and Protective Action Decision Frameworks

The theoretical frameworks of risk communication and protective action decision making, namely, the WPF by McLuckie [32], the WRM by Quarantelli [33], and the PDM by Lindell [34], remain relevant today. These frameworks conceptualize the stages of risk communication from sender and receiver perspectives, involving the creation, dissemination, flow, and monitoring of information as well as the receipt of that information and its influence on behavioral responses. While these processes remain the same, this study indicates that channels and content have significantly evolved. The findings of this study make plain that the plethora of channels available in today’s information environment muddy the flow of risk communication. The emergency managers we interviewed do not know which channels are most preferred by the public (Challenge 1) nor those that are most effective in reaching and engaging different groups of the public (Challenges 2 and 3). This information, which we believe can be gained through future research, could help dial in the circuits that run from external risk information receipt and gathering to appropriate protective action. However, even with these pathways illuminated, misinformation may obstruct the flow of risk information.

The findings of this study have pointed out the difficulty in identifying credible, reliable information on the receiver side (Challenge 5) and managing the presence and prevalence of misinformation and disinformation on the sender side (Challenge 6). The presence of inaccurate information can affect information search behavior and protective action decision making. When encountering misinformation, they may spend time confirming that message from different sources, which may delay the protective action decision. Misinformation may also lead the individual to believe that they are responding in line with what they believe to be credible information, which in turn could result in a sub-optimal protective action decision. Moreover, inaccurate risk information may influence one’s perception of the hazard, protective action, and trustworthiness of official sources.

In all, misinformation can lead to misguided actions during disasters [58], which has important implications for the application of prevailing theories of risk communication and protective action decisions. Combating misinformation with effective messages, ones that motivate receivers to take the recommended protective action, remains an important area of future research. Because technologies are rapidly changing, research needs to address how emergency managers may assess message effectiveness while channels evolve (Challenge 4).

5.2. Implications for Risk Communication Practices

Beyond theoretical implications, this study has significant take-away messages for risk communicators. The findings point to the need for communication strategies that improve risk information awareness. This includes awareness of where/how to access official channels and what to expect in terms of the content, source, and timing of risk information. This will require active collaboration between emergency management agencies, local officials, media and news firms, and groups of the public. Greater awareness of official risk information channels and an understanding of risk messaging will help cut through the noise (Challenge 5) of the multitude of channels available as well as help people to tune in (by knowing where and how) instead of tuning out (Challenge 3).

Given that the use of communication channels by the public has shifted in the past twenty years, local emergency managers need to identify effective channels that can be used to reach different populations (Challenges 1 and 2). In particular, understanding the social media platforms utilized by the public is key, as people continue to rely on channels such as Facebook, X, and Instagram for information. This will require robust knowledge production between researchers who study the preferences of various groups for different risk communication channels and the practitioners who use these channels and see their impact on the ground. An exploration of not only the channels but also the messages that most resonate with different groups of the public (Challenge 4) will help to develop strategies that will improve risk communication in today’s information environment.

Critically, the findings of this study underscore that reliable risk information is needed. This involves further development of strategies to combat misinformation (Challenge 6) but also experimentation into how risk communication messaging may be refreshed, reframed, and re-established with the public (Challenge 7). The emergency managers we interviewed noted that public confidence in official sources of risk communication has been damaged by COVID-19. This calls into question how and what is communicated through risk messaging.

The findings also underscore the importance of relationship building for risk communication. In order for risk communication to be effective during a disaster, building trust with the public before an event occurs is essential. Strategies to improve relationships include engaging with groups of the public and community partners during non-disaster phases of hazard management (e.g., hazard assessments and mitigation planning) and in other settings outside of traditional emergency management venues (e.g., schools, churches, and assisted-living facilities). Emergency managers can also work with other local and state stakeholders when conducting disaster drills and exercises to simulate how information will be gathered, assessed, and shared with local, state, nonprofit, and private entities, as well as with the public. Understanding the roles different entities play in communicating risks, as well as being knowledgeable of the different channels and resources utilized by other stakeholders, can help increase the breadth and reach of warning messages during an event. Establishing relationships and a strong rapport with the public and key stakeholders before an event can help emergency managers address challenges stemming from misinformation (Challenge 6), quiet the abundance of “noise” (Challenge 5), and restore trust in official sources during a disaster (Challenge 7).

Overall, the challenges identified in this study call for disaster science researchers and emergency managers to revisit the mechanisms of external information receiving and gathering and to consider how these influence internal perception-formation processes and behavioral responses. Further research is needed to explore what a re-envisioned approach to hurricane messaging might look like. Studies should focus on channel preferences, message effectiveness, and the mediating roles of misinformation and trust.

6. Conclusions

Risk communication is a foundational component of disaster and emergency management research and practice. It is central to the protection of people and their assets as well as to building community capacity for resilience to disasters [31]. This study has explored how risk communication has changed, given the shifts in natural hazard profiles due to climate change and the dynamics of the digital era of communication. Our research questions have examined three aspects of communication—the selection of channels, message effectiveness, and the management of misinformation—using data gathered in interviews with Texas coastal emergency managers about these issues during hurricane events. We found that most emergency management offices use a multiple-channel approach, including the use of various types of social media. Additionally, we found that message effectiveness is typically assessed using available metrics on information uptake (but not behavior). Finally, it was evident from the interview data that misinformation is a fixture of today’s information environment, with some of it having benign roots, while other inaccuracies are intentional, and all divert limited resources.

Based on these findings, we identify seven key challenges facing risk communication today. These include (1) a limited understanding of channel preferences among various subgroups of the public, (2) a selection of the “right” channels of communication for events of varying severity, (3) avoiding people “tuning out” of emergency management channels, (4) limited resources and methods for assessing message effectiveness, (5) cutting through the “noise” of misinformation, (6) managing misinformation with multiple strategies, and (7) avoiding stale risk messages that may encourage misinformation. These findings have important implications for the application of prevailing risk communication and protective action decision frameworks in today’s information age. They also point to the need for researchers and risk communicators to co-produce strategies to combat misinformation, engage different groups of the public, and identify the channels that will most effectively disseminate risk information.

Despite these contributions, this study has multiple limitations. Chief among these is that it explores only the Texas Gulf Coast. Additionally, the interview questions focus on the experiences of emergency managers and risk communication in the context of hurricane scenarios. While the findings are transferable to similar events in similar geographic contexts (i.e., coastal communities), caution should be used when considering the broader applicability of the findings presented in this paper, as different locations and hazards may present different challenges and require different strategies for more effective risk and warning communication. Additionally, the interviews were conducted following Hurricane Beryl; therefore, though the reporting of challenges may be current, it is possible that participants were sharing experiences and information more closely tied to that particular event rather than discussing a range of events over the past several years.

This study lays the foundation for future research to address the limitations discussed, expand upon the findings, and potentially call for modifications to risk communication theories and models such as the WRM or PADM. Given that the digital age amplifies the impact of misinformation, the theoretical contribution of this paper suggests a closer examination of how misinformation can affect the selection of risk information sources, communication channels, and responses. Polling the public and conducting experimental studies may be helpful in elucidating how people seek out information, tune in, interpret, and act on risk messages in today’s digital era. These quantitative investigations would complement the qualitative analysis of this study. This study approached risk communication from the sender perspective of emergency managers; future work is needed to investigate the receiver perspective. Such investigations should pay attention not only to communication channels and messages but also, as guided by existing risk communication theories, to receiver sociodemographic characteristics, disaster experience, social and environmental cues, and culture. The findings of this study also point to trust in information sources and awareness of misinformation as important factors to evaluate for receivers of risk communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.R., L.S. and H.-C.W.; data curation, S.K. and M.S.; formal analysis, A.D.R.; funding acquisition, A.D.R., L.S. and H.-C.W.; methodology, A.D.R., L.S. and H.-C.W.; project administration, A.D.R., L.S. and H.-C.W.; supervision, A.D.R.; visualization, A.D.R.; writing—original draft, A.D.R., L.S., H.-C.W., S.K., S.N. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.D.R., L.S., H.-C.W., S.K. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was paid for in part with federal funding from the Department of the Treasury through the State of Texas under the Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act of 2012 (RESTORE Act). The content, statements, findings, opinions, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the State of Texas or the Treasury.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Texas A&M University (MOD00000590, approved: 3 June 2024) and the University of North Texas (IRB-24-296, approved: 5 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available through GRIIDC Gulf Science Data Repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Meterological Association. The Global Climate 2011–2020: A Decade of Accelerating Change; World Meterological Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, R. Climate Change: Global Sea Level Rise. Cliamte.gov. 22 April 2023. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Lindsey, R.; Dahlman, L. Climate Change: Global Temperature. Climate.gov. 18 January 2024. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Committee on Extreme Weather Events and Climate Change Attribution, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, Division on Earth and Life Studies, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 21852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Bohrer, G.; Stagge, J.H. Centennial-Scale Intensification of Wet and Dry Extremes in North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment; Crimmins, A.R., Avery, C.W., Easterling, D.R., Kunkel, K.E., Stewart, B.C., Maycock, T.K., Eds.; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I. Disaster by Choice: How Our Actions Turn Natural Hazards into Catastrophes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, S.D.; Gunn, J.; Peacock, W.; Highfield, W.E. Examining the Influence of Development Patterns on Flood Damages along the Gulf of Mexico. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debortoli, N.S.; Camarinha, P.I.M.; Marengo, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R. An index of Brazil’s vulnerability to expected increases in natural flash flooding and landslide disasters in the context of climate change. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogger, M.; Agnoletti, M.; Alaoui, A.; Bathurst, J.C.; Bodner, G.; Borga, M.; Chaplot, V.; Gallart, F.; Glatzel, G.; Hall, J.; et al. Land use change impacts on floods at the catchment scale: Challenges and opportunities for future research. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 5209–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M. What’s Driving the Boom in Billion-Dollar Disasters? A Lot. Pew Trusts. 12 October 2023. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/10/12/whats-driving-the-boom-in-billion-dollar-disasters-a-lot (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Liedke, J.; Wang, L. Social Media and News Fact Sheet. Pew Res. Cent. November 2023. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Pian, W.; Chi, J.; Ma, F. The causes, impacts and countermeasures of COVID-19 “Infodemic”: A systematic review using narrative synthesis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Y.M.; de Moura, G.A.; Desidério, G.A.; de Oliveira, C.H.; Lourenço, F.D.; De Figueiredo Nicolete, L.D. The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.-C.; Pierri, F.; Hui, P.-M.; Axelrod, D.; Torres-Lugo, C.; Bryden, J.; Menczer, F. The COVID-19 Infodemic: Twitter versus Facebook. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 20539517211013861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Jurkowitz, M.; Oliphant, B.; Shearer, E. How Americans Navigated the News in 2020: A Tumultuous Year in Review. Pew Research Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/02/22/how-americans-navigated-the-news-in-2020-a-tumultuous-year-in-review/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Kennedy, B.; Tyson, A.; Funk, C. Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines. Pew Research Center. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2022/02/PS_2022.02.15_trust-declines_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Latkin, C.A.; Dayton, L.; Strickland, J.C.; Colon, B.; Rimal, R.; Boodram, B. An assessment of the rapid decline of trust in US sources of public information about COVID-19. In Vaccine Communication in a Pandemic; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Archer, P.; Kruger, E.; Mallonee, S. Tornado-Related Deaths and Injuries in Oklahoma due to the 3 May 1999 Tornadoes. Weather. Forecast. 2002, 17, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.; Huntsman, D.; Wu, H.-C.; Murphy, H.; Clay, L. Household hurricane evacuation during a dual-threat event: Hurricane Laura and COVID-19. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jon, I.; Lindell, M.K.; Prater, C.S.; Huang, S.-K.; Wu, H.-C.; Johnston, D.M.; Becker, J.S.; Shiroshita, H.; Doyle, E.E.; Potter, S.H.; et al. Behavioral Response in the Immediate Aftermath of Shaking: Earthquakes in Christchurch and Wellington, New Zealand, and Hitachi, Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Lu, J.-C.; Prater, C.S. Household Decision Making and Evacuation in Response to Hurricane Lili. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2005, 6, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagele, D.E.; Trainor, J.E. Geographic Specificity, Tornadoes, and Protective Action. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2012, 4, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebeneck, L.; Schumann, R.; Kuenanz, B.-J.; Lee, S.; Benedict, B.C.; Jarvis, C.M.; Ukkusuri, S.V. Returning home after Superstorm Sandy: Phases in the return-entry process. Nat. Hazards 2020, 101, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-L.; Lindell, M.K.; Prater, C.S. “Certain Death” from Storm Surge: A Comparative Study of Household Responses to Warnings about Hurricanes Rita and Ike. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2014, 6, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Murphy, H.; Greer, A.; Clay, L. Evacuate or social distance? Modeling the influence of threat perceptions on hurricane evacuation in a dual-threat environment. Risk Anal. 2023, 44, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borah, P.; Lorenzano, K.; Vishnevskaya, A.; Austin, E. Conservative Media Use and COVID-19 Related Behavior: The Moderating Role of Media Literacy Variables. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, E.F.; Chen, M.K.; Rohla, R. Political storms: Emergent partisan skepticism of hurricane risks. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manandhar, R.; Siebeneck, L.K. Information management and the return-entry process: Examining information needs, sources, and strategies after Superstorm Sandy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, K.E.; Botan, C.H.; Kreps, G.L.; Samoilenko, S.; Farnsworth, K. Risk communication education for local emergency managers: Using the CAUSE model for research, education, and outreach. In Handbook of Risk and Crisis Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 168–191. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n15/291/89/pdf/n1529189.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- McLuckie, B. The Warning System in Disaster Situations: A Selective Analysis; University of Delaware: Newark, Delaware, 1970; Available online: https://udspace.udel.edu/items/75c5eeb7-5f69-47f5-bb55-370ea88b989e (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Quarantelli, E.L. The Warning Process and Evacuation Behavior: The Research Evidence; University of Delaware: Newark, Delaware, 1990; Available online: https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/b3929a5d-d544-4027-8b32-287a5a6514e4/content (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Lindell, M.K. Communicating Imminent Risk. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 449–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Perry, R.W. The Protective Action Decision Model: Theoretical Modifications and Additional Evidence. Risk Anal. 2011, 32, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileti, D.S.; Sorensen, J.H. Communication of Emergency Public Warnings: A Social Science Perspective and State-of-the-Art Assessment; ORNL-6609, 6137387; Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, J.; Fischer, L.M. Understanding Visual Risk Communication Messages: An Analysis of Visual Attention Allocation and Think-Aloud Responses to Tornado Graphics. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2021, 13, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.M.; Mileti, D.S.; Kano, M.; Kelley, M.M.; Regan, R.; Bourque, L.B. Communicating Actionable Risk for Terrorism and Other Hazards⋆. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.; Huntsman, D.; Orton, G.; Sutton, J. You Have to Send the Right Message: Examining the Influence of Protective Action Guidance on Message Perception Outcomes across Prior Hazard Warning Experience to Three Hazards. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2023, 15, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, J.; Renshaw, S.L.; Vos, S.C.; Olson, M.K.; Prestley, R.; Ben Gibson, C.; Butts, C.T. Getting the Word Out, Rain or Shine: The Impact of Message Features and Hazard Context on Message Passing Online. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2019, 11, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]