A Review of Studies on the Mechanisms of Cultural Heritage Influencing Subjective Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Defining Well-Being and Cultural Heritage

2.1.1. Well-Being

2.1.2. Cultural Heritage

2.2. Theories Related to Culture and Subjective Well-Being

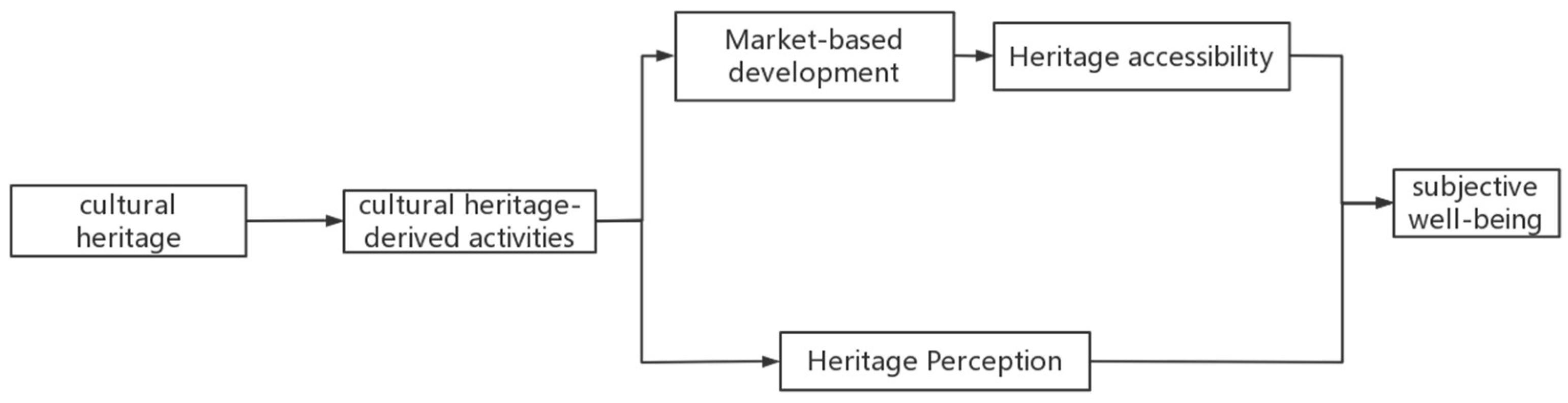

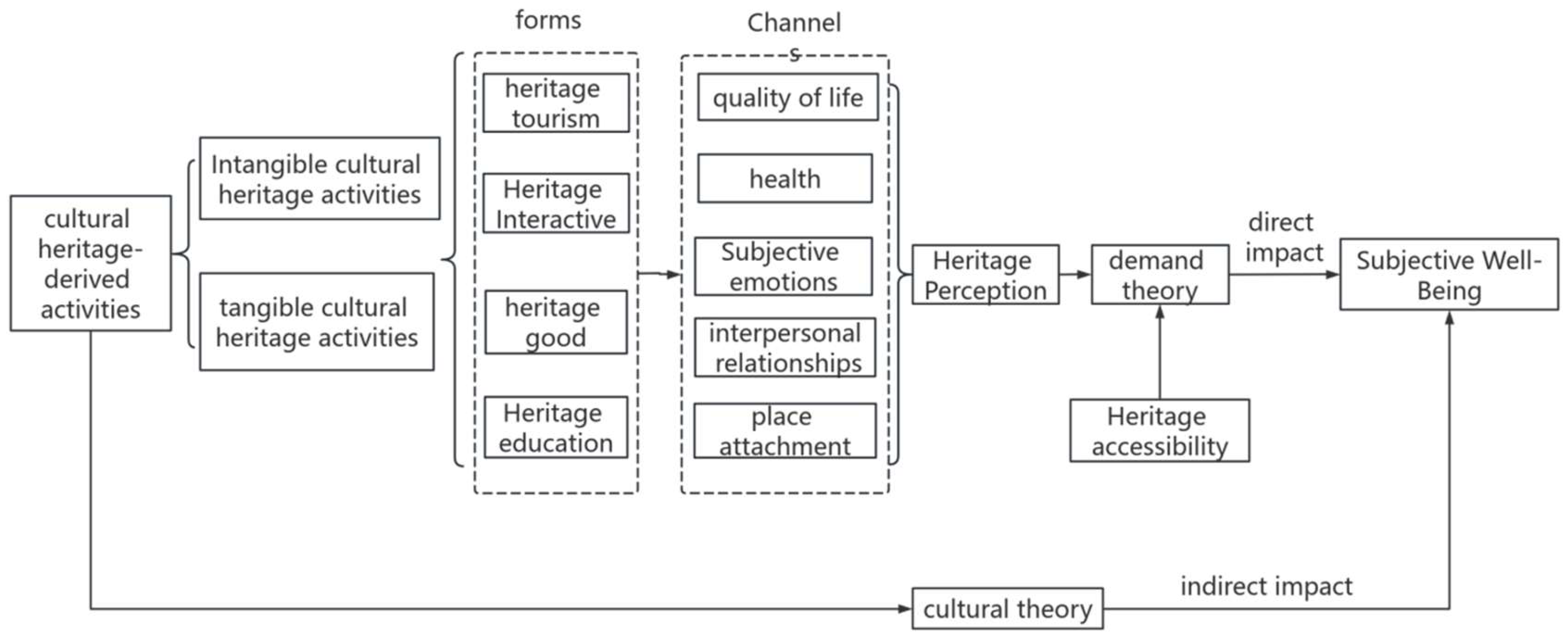

2.3. Study of the Mechanism by Which Cultural Heritage Affects the Subjective Well-Being

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. The Relationship Between Cultural Heritage-Derived Activities and Subjective Well-Being

4.2. The Relationship Between Intangible Cultural Heritage-Derived Activities and Subjective Well-Being

4.3. The Relationship Between Tangible Cultural Heritage-Derived Activities and Subjective Well-Being

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions & Outlook

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Research Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, A. The Theory of Moral Sentiments; Gutenberg: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jevons, W.S. The Theory of Political Economy; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1879. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Alier, J.; Pascual, U.; Vivien, F.-D.; Zaccai, E. Sustainable de-growth: Mapping the context, criticisms and future prospects of an emergent paradigm. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C. Happiness and health: Lessons—And questions—For public policy. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S. The Promise of Happiness Communication Culture & Critique; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010; Volume 4, pp. 419–421. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Soc. Indic. Res. 1994, 31, 103–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Xia, Z.; Lao, Y. Does cultural resource endowment backfire? Evidence from China’s cultural resource curse. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1110379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keitumetse, S. Cultural resources as sustainability enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) model. Sustainability 2014, 6, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Farid, A.M. Conservation of culture heritage tourism: A case study in Langkawi Kubang Badak Remnant Charcoal Kilns. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigo, M. Cultural property v. cultural heritage: A “battle of concepts” in international law? Int. Rev. Red Cross 2004, 86, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dromgoole, S. 2001 UNESCO convention on the protection of the underwater cultural heritage. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2003, 18, 59–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellegen, A.; Lykken, D.T.; Bouchard TJJr Wilcox, K.J.; Segal, N.L.; Rich, S. Personality similarity in twin reared apart and together. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Eunkook, M.S.; Richard, E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, V.S.; Bond, M.H.; Singelis, T.M. Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: Adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 1038–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollamparambil, U. Happiness, happiness inequality and income dynamics in South Africa. J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 21, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, D.; Ye, X. Income comparison and happiness: The role of fair income distribution. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2021, 60, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Campen, C.; Iedema, J. Are persons with physical disabilities who participate in society healthier and happier? Structural equation modelling of objective participation and subjective well-being. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun, B.; Cesur, R. Transforming lives: The impact of compulsory schooling on hope and happiness. J. Popul. Econ. 2016, 29, 911–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrensel, A.Y. Happiness, economic freedom and culture. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2015, 22, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficarra, L.; Rubino, M.J.; Morote, E.-S. Does Organizational Culture Affect Employee Happiness? J. Leadersh. Instr. 2020, 19, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Heo, S. Arts and cultural activities and happiness: Evidence from Korea. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1637–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D.; Bickerton, C. Measuring changes in subjective well-being from engagement in the arts, culture and sport. J. Cult. Econ. 2019, 43, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, I. Cultural heritage rights: From ownership and descent to justice and well-being. Anthropol. Q. 2010, 83, 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y. Impact of green space on residents’ wellbeing: A case study of the Grand Canal (Hangzhou section). Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1146892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calma, T.; Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing and mental health. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateca-Amestoy, V.; Villarroya, A.; Wiesand, A.J. Heritage engagement and subjective well-being in the European Union. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, F. A Mechanism for Measuring the Impact of Heritage Practice on Well-Being. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Heritage Theory and Practice; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2018; p. 387. [Google Scholar]

- Darvill, T.; Heaslip, V.; Barrass, K. Heritage and well-being: Therapeutic places, past and present. In Routledge Handbook of Well-Being; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Koldijk, L. Cultural Heritage Proximity and Its Effect on Subjective Well-Being: A Case Study in Groningen, The Netherlands. Ph.D. Thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Shen, C.; Wang, E.; Hou, Y.; Yang, J. Impact of the perceived authenticity of heritage sites on subjective well-being: A study of the mediating role of place attachment and satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolal, M.; Gursoy, D.; Uysal, M.; Karacaoğlu, S. Impacts of festivals and events on residents’ well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, L.; Frey, B.; Hotz, S. European capitals of culture and life satisfaction. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, J. The impact of music festival attendance on young people’s psychological and social well-being. Psychol. Music. 2011, 39, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, H.; Xiao, H. Are authentic tourists happier? Examining structural relationships amongst perceived cultural distance, existential authenticity, and wellbeing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokić, B.; Purić, D. Does cultural participation make us happier? Favorite leisure activities and happiness in a representative sample of the Serbian population. Kultura 2020, 169, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupp, M.D.; Bignardi, G.; Chana, K.; Specker, E.; Pelowski, M. Can a brief interaction with online, digital art improve wellbeing? A comparative study of the impact of online art and culture presentations on mood, state-anxiety, subjective wellbeing, and loneliness. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 782033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.W.; Coulter, R.; Fancourt, D. Associations between community cultural engagement and life satisfaction, mental distress and mental health functioning using data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS): Are associations moderated by area deprivation? BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapacciuolo, A.; Perrone Filardi, P.; Cuomo, R.; Mauriello, V.; Quarto, M.; Kisslinger, A.; Savarese, G.; Illario, M.; Tramontano, D. The Impact of Social and Cultural Engagement and Dieting on Well-Being and Resilience in a Group of Residents in the Metropolitan Area of Naples. J. Aging Res. 2016, 2016, 4768420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertacchini, E.; Bolognesi, V.; Venturini, A. The Happy Cultural Omnivore? Exploring the Relationship between Cultural Consumption Patterns and Subjective Well-Being. IZA Discuss. Pap. 2021, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.; Sacco, P.L.; Blessi, G.T.; Cerutti, R. The impact of culture on the individual subjective well-being of the Italian population: An exploratory study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2011, 6, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercsey, I.; Józsa, L. The effect of the perceived value of cultural services on the quality of life. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2016, 13, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, A.C. Arts and the quality of life: An exploratory study. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 71, 11–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, I. Great expectations: Education and subjective wellbeing. J. Econ. Psychol. 2018; 66, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Olshavsky, R.W.; King, M.F. Exploring Alternative Antecedents of Customer Delight. J. Consum. Satisf. 2001, 14, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cocozza, S.; Sacco, P.L.; Matarese, G.; Maffulli, G.D.; Maffulli, N.; Tramontano, D. Participation to leisure activities and well-being in a group of residents of Naples-Italy: The role of resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; MacDonald, R.; Mitchell, R. Are people who participate in cultural activities more satisfied with life? Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D.; Bickerton, C. Subjective well-being and engagement in arts, culture and sport. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Olejnik, A.; Schirpke, U.; Tappeiner, U. A systematic review on subjective well-being benefits associated with cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 57, 101467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liang, Z.; Ritchie, B.W. Residents’ social dilemma in sustainable heritage tourism: The role of social emotion, efficacy beliefs and temporal concerns. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1782–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Lin, V.S.; Xiao, H. Integrating authenticity, well-being, and memorability in heritage tourism: A two-site investigation. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanagustín-Fons, M.V.; Tobar-Pesántez, L.B.; Ravina-Ripoll, R. Happiness and cultural tourism: The perspective of civil participation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, S. Disparate Emotions as Expressions of Well-Being: Impact of Festival Participation from the Participants’ Subjective View. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, T.D.T.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: The case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-j.; Kang, E.M.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Zielinski, S. Relationships between community festival participation, social capital, and subjective well-being in a cross-cultural context. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellard, I. Body-reflexive pleasures: Exploring bodily experiences within the context of sport and physical activity. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Humphreys, B.R. Sports participation and happiness: Evidence from US microdata. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillo-Albert, A.; Sáez de Ocáriz, U.; Costes, A.; Lavega-Burgués, P. From conflict to socio-emotional well-being. Application of the GIAM model through traditional sporting games. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K.; Coghlan, A. Exploring the positive psychology domains of well-being activated through charity sport event experiences. Event Manag. 2016, 20, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrecht, J.; Andersson, T.D. The event experience, hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction and subjective well-being among sport event participants. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2019, 4, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavega-Burgués, P.; Bortoleto, M.A.C.; Pic, M. Editorial: Traditional Sporting Games and Play: Enhancing Cultural Diversity, Emotional Well-Being, Interpersonal Relationships and Intelligent Decisions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 766625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downward, P.; Rasciute, S. Does sport make you happy? An analysis of the well-being derived from sports participation. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2011, 25, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gick, M.L. Singing, health and well-being: A health psychologist’s review. Psychomusicology Music Mind Brain 2011, 21, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghetti, C.M. Active music engagement with emotional-approach coping to improve well-being in liver and kidney transplant recipients. J. Music. Ther. 2011, 48, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papinczak, Z.E.; Dingle, G.A.; Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Zelenko, O. Young people’s uses of music for well-being. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.S. Preserving the consciousness of a nation: Promoting “Gross National Happiness” in Bhutan through her rich oral traditions. Storytell. Self Soc. 2006, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanis, E. Participation in socio-cultural activities and subjective well-being of natives and migrants: Evidence from Germany and the UK. Int. Rev. Econ. 2021, 68, 423–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Zheng, T.; Xiang, Z.; Zhang, M. Visiting intangible cultural heritage tourism sites: From value cognition to attitude and intention. Sustainability 2019, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S. Wisdom on the Pursuit of Happiness in Daily Life. Christmas Celebrations in the German Family. Paragrana 2013, 22, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sektani, H.H.J.; Khayat, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Roders, A.P. Factors linking perceptions of built heritage conservation and subjective wellbeing. Herit. Soc. 2023, 16, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, J.; Curtis, A.; Mendham, E.; Toman, E. Cultural landscapes at risk: Exploring the meaning of place in a sacred valley of Nepal. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 52, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Shariff, M.K.B.M. The Concept of Place and Sense of Place in Architectural Studies. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 80, 1100. [Google Scholar]

- Rollero, C.; Piccoli, N.D. Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Sacco, P.L. Magic moments: Determinants of stress relief and subjective wellbeing from visiting a cultural heritage site. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2019, 43, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, H.J.; Camic, P.M. The Health and Well-Being Potential of Museums and Art Galleries; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ander, E.; Thomson, L.; Noble, G. Heritage, health and well-being: Assessing the impact of a heritage focused intervention on health and well-being. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.; Beel, D. Researching Happiness. In How Cultural Heritage Can Contribute to Community Development and Wellbeing; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2021; pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Belver, M.H.; Ullán, A.M.; Avila, N.; Noreno, C.; Hernandez, C. Art museums as a source of well-being for people with dementia: An experience in the Prado Museum. Arts Health 2018, 10, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerholm, N.; Martín-López, B.; Torralba, M.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Lechner, A.M.; Bieling, C.; Olafsson, A.S.; Albert, C.; Raymond, C.M. Perceived contributions of multifunctional landscapes to human well-being: Evidence from 13 European sites. People Nat. 2020, 2, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.-C. Expanding the Concept of Cultural Heritage Utilization and Classifying the Types. Munhwajae Korean J. Cult. Herit. Stud. 2014, 47, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.L.; Estêvão, G. Design and Culture in the Making of Happiness. In Proceedings of the Advances in Design, Music and Arts: 7th Meeting of Research in Music, Arts and Design, EIMAD, Castelo Branco, Portugal, 14–15 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Puig, A.; Lee, S.M.; Goodwin, L.; Sherrard, D. The efficacy of creative arts therapies to enhance emotional expression, spirituality, and psychological well-being of newly diagnosed Stage I and Stage II breast cancer patients: A preliminary study. Arts Psychother. 2006, 33, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | Forms | Channels | Effect | Related Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undifferentiated | heritage tourism | quality of life | +/− | Steiner (2015); Medet Yolal (2016) [32,33] |

| health | nil | |||

| subjective emotions | + | Jan Packer (2011) [34] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Jan Packer (2011); Jibin Yu (2019) [34,35] | ||

| place attachment | + | Jibin Yu (2019) [35] | ||

| channel not mentioned | nil | |||

| Heritage Interactive | quality of life | + | Jokić Biljana (2020) [36] | |

| health | + | Jokić Biljana (2020) [36] | ||

| subjective emotions | + | Hei Wan Mak (2021); MacKenzie D. Trupp (2022) [37,38] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Jokić Biljana (2020); Hei Wan Mak (2021) [36,37] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | + | Antonio Rapacciuolo (2016) [39] | ||

| heritage good | quality of life | + | Bertacchini (2021) [40] | |

| health | + | Enzo Grossi (2011); Bertacchini (2021) [40,41] | ||

| subjective emotions | + | Victoria Ateca-Amestoy(2016) [27] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Ida Ercsey (2016); Victoria Ateca-Amestoy (2016); Bertacchini (2021) [27,40,42] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | + | Enzo Grossi (2011) [41] | ||

| Heritage education | quality of life | + | Alex C. Michalos (2017) [43] | |

| health | +/Ø | Alex C. Michalos (2017); Ingebjorg Kristoffersen (2018) [43,44] | ||

| subjective emotions | + | Kumar (2001) [45] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | nil | |||

| place attachment | ||||

| channel not mentioned | + | Daniel Wheatley(2019) [23] | ||

| Undifferentiated form | quality of life | nil | ||

| health | + | Sergio Cocozza (2020) [46] | ||

| subjective emotions | + | Daniel Wheatley (2019) [23] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Jennifer L. Brown (2015); Daniel Wheatley (2019) [23,47] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | +/−/Ø | Agnieszka Nowak-Olejnik (2005); Jennifer L. Brown (2015); Daniel Wheatley (2017) [47,48,49] | ||

| Intangible Cultural Heritage | heritage tourism | quality of life | +/Ø | Danni Zheng (2020) [50] |

| health | nil | |||

| subjective emotions | + | M. Victoria Sanagustín-Fons (2020); Xiaoli Yi (2021) [51,52] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | M. Victoria Sanagustín-Fons (2020); Xiaoli Yi (2021); Saeid Abbasian (2023) [51,52,53] | ||

| place attachment | + | Thuy D. T. Hoang (2020) [54] | ||

| channel not mentioned | + | Young-joo Ahn (2023) [55] | ||

| Heritage Interactive | quality of life | nil | ||

| health | + | Haifang Huang (2012); Ian Wellard Ian (2012); [56,57] | ||

| subjective emotions | +/− | Ian Wellard Ian (2012); Kevin Filo (2016); John Armbrecht (2020); Pere Lavega-Burgués (2021); Aaron Rillo-Albert (2021) [56,58,59,60,61] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Paul Downward (2011); Kevin Filo (2016) [59,62] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | ||||

| heritage good | quality of life | |||

| health | + | Mary L. (2011) [63] | ||

| subjective emotions | + | Puig (2006); Claire M. Ghetti (2011); Zoe E. Papinczak (2015) [64,65] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | A. Steven Evans (2006) [66] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | + | Mary L. (2011); Eleftherios Giovanis (2021) [63,67] | ||

| Heritage education | quality of life | nil | ||

| health | ||||

| subjective emotions | nil | Qihang Qiu (2020) [68] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Suzuki (2013) [69] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | ||||

| Tangible Cultural Heritage | heritage tourism | quality of life | nil | |

| health | ||||

| subjective emotions | + | Sektani, Hawar Himdad J. (2023) [70] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Najafi (2011); Jennifer Sherry (2018); Sektani, Hawar Himdad J. (2023) [70,71,72] | ||

| place attachment | + | Rollero (2010); Jennifer Sherry (2018); Sektani, Hawar Himdad J. (2023) [70,71,73] | ||

| channel not mentioned | + | Enzo Grossi (2019) [74] | ||

| Heritage Interactive | quality of life | nil | ||

| health | ||||

| subjective emotions | + | Erica E Ander (2013); Helen J. Chatterjee (2015); Beel (2021) [75,76,77] | ||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Helen J. Chatterjee (2015); Manuel H. Belver (2018); Beel (2021); Lee (2021) [22,75,77,78] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | ||||

| Heritage education | quality of life | |||

| health | ||||

| subjective emotions | ||||

| interpersonal relationships | + | Nora Fagerholm (2020) [79] | ||

| place attachment | nil | |||

| channel not mentioned | + | Sektani, Hawar Himdad J. (2023) [70] | ||

| Forms of Derivation of Cultural Heritage Activities | Elements | Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Cultural Heritage | Intangible Cultural Heritage | Undifferentiated | ||

| heritage tourism | quality of life | nil | +/− | +/− |

| health | nil | nil | nil | |

| subjective emotions | + | + | + | |

| interpersonal relationships | + | + | + | |

| place attachment | + | + | + | |

| element not mentioned | + | + | nil | |

| heritage Interactive | quality of life | nil | nil | + |

| health | nil | + | + | |

| subjective emotions | + | +/− | + | |

| interpersonal relationships | + | + | + | |

| place attachment | nil | nil | nil | |

| element not mentioned | nil | nil | + | |

| heritage good | quality of life | nil | nil | + |

| health | nil | + | + | |

| subjective emotions | nil | + | + | |

| interpersonal relationships | nil | + | + | |

| place attachment | nil | nil | nil | |

| element not mentioned | nil | + | + | |

| heritage education | quality of life | nil | nil | + |

| health | nil | nil | +/−/Ø | |

| subjective emotions | nil | nil | + | |

| interpersonal relationships | + | + | nil | |

| place attachment | nil | nil | nil | |

| element not mentioned | + | nil | + | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, S.; Li, H.; Yu, Z. A Review of Studies on the Mechanisms of Cultural Heritage Influencing Subjective Well-Being. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410955

Kong S, Li H, Yu Z. A Review of Studies on the Mechanisms of Cultural Heritage Influencing Subjective Well-Being. Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):10955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410955

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Shaohua, Hanzun Li, and Ziyi Yu. 2024. "A Review of Studies on the Mechanisms of Cultural Heritage Influencing Subjective Well-Being" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 10955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410955

APA StyleKong, S., Li, H., & Yu, Z. (2024). A Review of Studies on the Mechanisms of Cultural Heritage Influencing Subjective Well-Being. Sustainability, 16(24), 10955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410955