Sustainability of the Origin Indication of Sugar Cane Spirit from Abaíra Microregion, Bahia, Brazil Under the Aegis of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

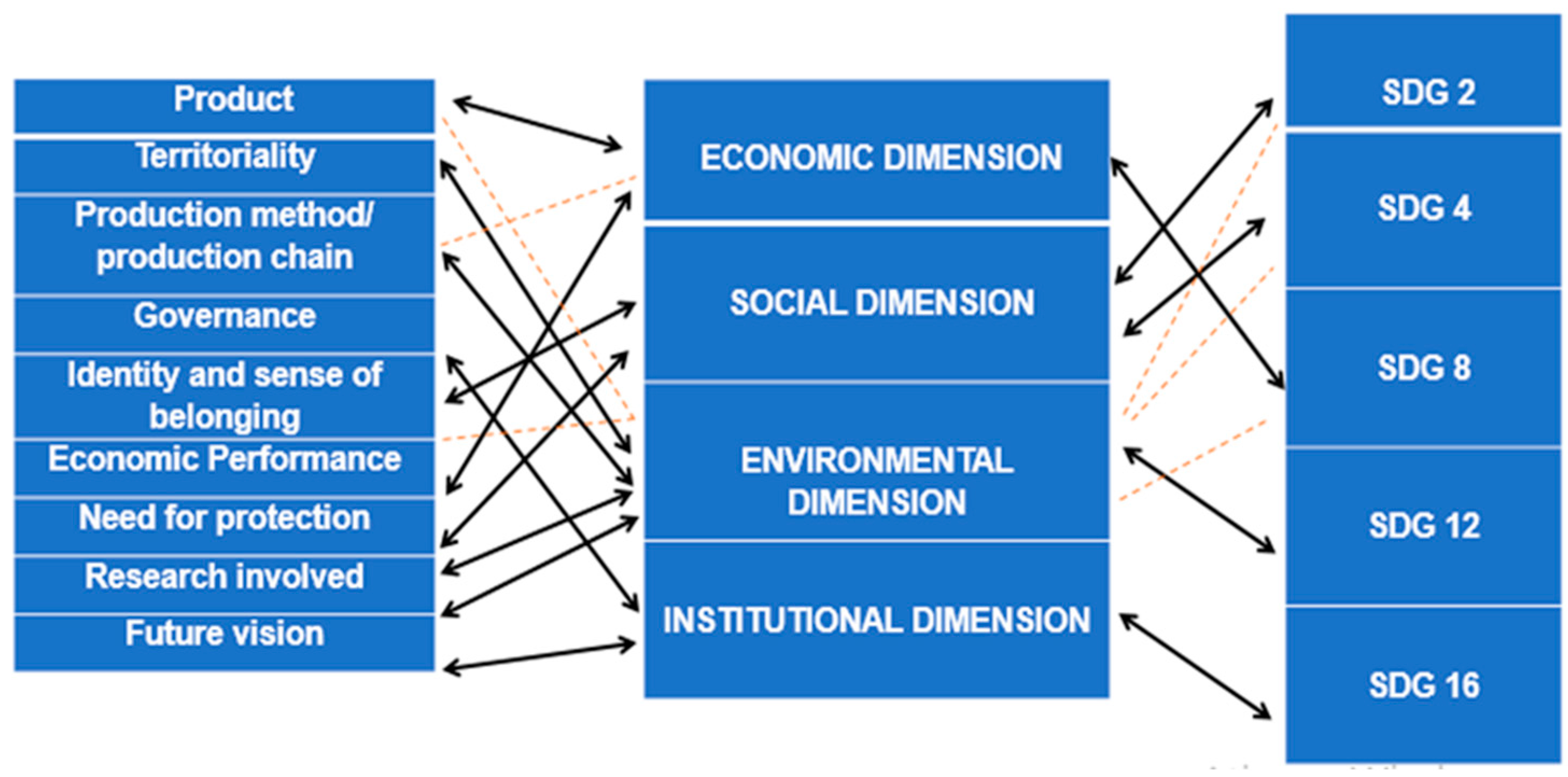

2. Dimensions of Sustainability, SDGs and GI

GI Characterization of Abaíra Microregion, Bahia, Brazil

3. Methodological Procedures

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Assessment of Sustainability Indicators in the Abaíra Microregion/BA Geographical Indication

4.1.1. Economic Dimension

4.1.2. Social Dimension

4.1.3. Environmental Dimension

4.1.4. Institutional Dimension

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Law No. 9,279, of May 14, 1996. Regulates Rights and Obligations Related to Industrial Property. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF, 15 Maio 1996. Seção 1, p. 8353. Recovered on 1 May 2022. 1996. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L8918.htm (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Vieira, A.C.P.; Zilli, J.C.F.; Bruch, K.L. Public Policies as an Instrument for Developing Geographical Indications. Rev. FOCO 2016, 9, 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuta, S.M.; Souza, A.L.; Schwanke, F.H.; Giesbrecht, H.O. Geographical Indications: Answer Guide; Sebrae/RS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, A.R. Geographical Indications as a Territorial Development Strategy: The Case of Goethe Grape Valleys. Master’s Thesis, Passo Fundo University, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração, Passo Fundo, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, K.F.S.; Braga, J.M.; Albino, P.M.B. Impact of Origin Indications on Municipal Development. Rev. Desenvolv. Reg. 2022, 19. Available online: https://seer.faccat.br/index.php/coloquio/article/view/2340 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- UN. The United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Translated by the United Nations Information Center for Brazil (UNIC Rio), Last Edited on 25 September 2015. Recovered on 1 May 2022. 2015. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/91863-agenda-2030-para-o-desenvolvimento-sustentavel (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Paulo Roberto Lisboa, A. Geographical Indication as a Promoter of Sustainable Territorial Development: The Cases of Goethe Grape Valley Region and Banana in the Corupá Region. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Socio-Economic Center, Postgraduate Program in Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer for Innovation, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rangnekar, D. The Socio-Economics of Geographical Indications: A Review of Empirical Evidence from Europe. Intellectual Property Rights and Sustainable Developmen, May 2004. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ictsd2004ipd8_en.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Fronzaglia, T. Challenges in evaluating geographical indications: A literature review. In Propriedade Intelectual, Desenvolvimento e Inovação: Desafios para o Futuro; Vieira, A.C.P., Bruch, K.L., Locatelli, L., Eds.; Aya: Ponta Grossa, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.C.P.; Pellin, V. As Indicações Geográficas como Estratégia para Fortalecer o Território: O caso da indicação de procedência dos vales da uva Goethe. Desenvolv. Questão 2015, 13, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mello, L.M.R.; Zackiewicz, M.; Bezerra, L.M.C.; Tonietto, J.; Beaulieu, C.M.G.; Caetano, S.F. Methodology for Assessing Economic, Social and Environmental Impacts for Geographical Indications: The Case of Vale dos Vinhedos—Bento Gonçalves: Embrapa Uva e Vinho. Recovered on 01 May 2022. 2014. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/1003871/metodologia-de-avaliacao-de-impactos-economicos-sociais-e-ambientais-para-indicacoes-geograficas-o-caso-do-vale-dos-vinhedos (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- INPI. Instituto Nacional de Propriedade Intelectual. ORDINANCE/INPI/PR No.04, of 12 January 2022. Establishes the Conditions for the Registration of Geographical Indications, Provides for the Reception and Processing of Requests and Petitions and the Geographical Indications Manual. Ministério da Economia, INPI. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/inpi/pt-br/servicos/indicacoes-geograficas/arquivos/legislacao-ig/PORT_INPI_PR_04_2022.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Jannuzzi, P.M.; Carlo, S. From the Millennium Development Agenda to Sustainable Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Planning and Public Policies in the 21st Century. Revista Bahia Análise e Dados. Salvador, v. 28, n. 2, pp. 6–27, Jul.-Dez. 2018. Recovered on 7 October 2021. 2018. Available online: http://www.cge.rj.gov.br/interativa/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Texto-complementar-3.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Barbieri, J.C. Sustainable Development: From Origins to the 2030 Agenda; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, P.R. Intangible Capitals and Regional Development. Rev. Econ. 2009, 35, 119–146. Available online: https://revistas.ufpr.br/economia/article/view/16712 (accessed on 24 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- WCED. World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future, 2nd ed.; Editora Fundação Getúlio Vargas—FGV: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 1991; Recovered on 1 October 2021; Available online: https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4245128/mod_resource/content/3/Nosso%20Futuro%20Comum.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Mendonça, D.; Procópio, D.P.; Corrêa, S.R.S. The Contribution of Geographical Indications to Brazilian Rural Development. Res. Soc. Dev. 2019, 8, e41871152. Available online: https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/1152 (accessed on 1 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Future We Want. UN: Rio de Janeiro. Recovered on 10 January 2023. 2012. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/733FutureWeWant.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Gevher, R.; Acet, H. Avrupa Birliğinde Sürdürülebilir Kalkinma Ve Yeşil Ekonominin Gelişimİ. Anadolu Üniversitesi İktisadi İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2023, 24, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DATASEBRAE. Diagnosis of Potential Brazilian Geographical Indications. Recovered on 30 May 2022. 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240619105201/https://datasebrae.com.br/diagnosticos-realizados-pelo-sebrae/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Cerdan, C.; Bruch, K.L.; da Silva, A.L.; Copetti, M.; Favero, K.C.; Locatelli, L. Geographical indication of agricultural products: Historical and current importance. Cerdan, C.; Bruch, K.; Silva, A.L. (Org.). Curso de Propriedade Intelectual & Inovação no Agronegócio: Módulo II, Indicação Geográfica. 2.ed. Brasília: MAPA; Florianópolis: SEaD/UFSC/FAPEU, 2010. Recovered on 1 May 2022. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230421091229/http://nbcgib.uesc.br/nit/ig/app/papers/0253410909155148.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Maués, A.A. Florianópolis Oyster: Advantages and Challenges for Obtaining a Geographical Indication. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Postgraduate Program in Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer for Innovation—PROFNIT, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.A.R. Opportunities and Obstacles to Protection Based on Indication of Origin for Biscuits from Vitória da Conquista. Technical Report. Master’s Thesis, Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, I. Estratégias de Transição para o Século XXI: Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente; Nobel: São Paulo, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Caldas, A.d.S. Designations of Origin as a Unit of Planning, Local Development and Social Inclusion. RDE—Rev. Desenvolv. Econ. 2003, 5, 25–32. Available online: https://revistas.unifacs.br/index.php/rde/article/view/492 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Dutra, D.R.; Machado, R.T.M.; Castro, C.C. Public and Private Actions in the Implementation and Development of the Geographical Indication of Coffee in Minas Gerais. Inf. GEPEC 2009, 13, 90–106. Available online: http://repositorio.ufla.br/jspui/handle/1/183 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Gatto, D.; Clauzet, M.; Lustosa, M.C. Environmental Governance and Geographical Indication: The Case of the Mangrove Origin Designation in Alagoas. Desenvolv. Reg. Debate 2019, 9, 229–247. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=570864650011 (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Valente, M.E.R.; Neves, N.d.A.; Perez, R.; Fernandes, L.R.R.d.M.V.; Lima, J.E.d.; Chaves, J.B.P. Geographical indication and quality of cachaças according to the perception of drink enthusiasts. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e2989108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Sustainable Development Indicators: Brazil 2015. In Coordenação de Recursos Naturais e Estudos Ambientais e Coordenação de Geografia. Estudos e Pesquisas, Informações Geográfica; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 2015; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, A.S.; Bezerra, M.C.L. The Role of Governance in Promoting the Sustainability of Public Policies in Brazil. Rev. Mestr. Profissionais 2014, 3. Available online: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/RMP/article/view/722 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Niederle, P.A. Development, institutions and agri-food markets: The uses of Geographical Indications. DRd Desenvolv. Reg. Debate 2014, 4, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachaça Abaíra. Recovered on 1 May 2022. 2022. Available online: https://cachacaabaira.com.br/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Silva, D.T.; Rezende, A.A.; Silva, M.S. Coopama and the Cachaça Baiana “Abaíra” Production Chain. REVER 2018, 7, 241–265. Available online: https://beta.periodicos.ufv.br/rever/article/view/3378 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Garrido, E.C. Geographical Indications in Bahia: The Legal Security of Know-How and the Challenges and Opportunities After Registration is Granted; Monograph (Undergraduate); Federal University of Bahia, Law School: Salvador, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, A.C. How to Design Research Projects, 5th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bockorni, B.R.S.; Gomes, A.F. Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research in the Administration Field. Rev. Ciências Empres. UNIPAR 2021, 22, 105–117. Available online: https://ojs.revistasunipar.com.br/index.php/empresarial/article/view/8346/4111 (accessed on 4 July 2024). [CrossRef]

| Criteria | GI Main Survey Points |

|---|---|

| Product | Product characteristics/qualities; product byproducts; product temporality; legal regulations. |

| Territoriality | Recognized geographic area; steps carried out in the area; producers based in the area. |

| Production method/Production chain | Existence of common practice or traditional way; production quality control; links of the production chain. |

| Governance | Organization representing local community; representativeness; competing organizations; interaction and relationship. |

| Identity and Sense of belonging | Shared values, beliefs, and principles; positive engagement for the territory development. |

| Need for protection | Evidence of product falsification on the market; requirement for guarantee of origin. |

| Research involved | Natural factors influencing product quality; human factors (know-how); link proof with the geographic environment; ICT studies. |

| Future Vision | Market expansion goals; goals related to the territory development. |

| Dimension | Features |

|---|---|

| Economic | Community involvement with the Abaíra Microregion GI in economic practices related to the sugar cane spirit (cachaça) production chain, aiming to market expansion, as well as to guarantee financial growth for the producer, his family, and the community itself. |

| Social | Guarantee of qualified occupation for the local community involved with the Abaíra Microregion GI, motivating them to value the productive activity and the GI general context. |

| Environmental | Reinforcement of sustainability practices aimed at the rational use of environmental resources. |

| Institutional | Guarantee of positive effects in the territory delimited by the Abaíra Microregion GI, involving public and private institutions and the community in general. |

| Future Vision | Market expansion goals; goals related to the territory development. |

| Dimension/Themes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Social | Environmental | Institutional |

| Economic impact on the producer. | Conditions for improving the life quality of producers. | Use of natural resources. | Institutional articulation and development of local actors. |

| Economic impact on the territory. | Conditions for social development in the production sector and the territory. | Use of agricultural inputs. | Strengthening partnerships for sustainable development. |

| The Average Land Cultivated by Sugarcane Producers: 0.7 Hectare. |

|---|

| Land market value: 2000.00 BRL/ha to 2500.00 BRL/ha (2014/2022—cooperative) 2350.00 BRL/ha in 2014 and 3850.00 BRL/ha (2014/2022—producers) |

| Access to credit: medium intensity level. Production costs: high intensity—aggravating the product flow process (consumer does not understand). |

| Investments: medium/high intensity (infrastructure, technology, quality control, good practices and training, besides expanding production). |

| Post-GI actions to improve raw material quality (more productive sugarcane varieties and pest control without the use of chemicals). |

| Economic Indicators | Cooperative | Producers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2022 | 2014 | 2022 | |

| Access to credit | Low (2) | Medium (3) | Absent (0) | Medium (3) |

| Production costs | Low (2) | High (4) | Very Low (1) | Medium (3) |

| Investments made in production | High (4) | Very High (1) | Low (2) | Medium (3) |

| Subtitle—intensity (i): 0 = none, absent; 1 = very low; 2 = low; 3 = medium; 4 = high; 5 = very high. | ||||

| Cooperative | Producers |

|---|---|

| Distribution among members of more productive sugarcane varieties. | Implementation of more productive sugarcane varieties in the activity. |

| Guidance for members on how to attack pests without using chemicals. | Increase in irrigated area. |

| Motivations to Produce in This Place | Cooperative and Producers |

|---|---|

| Family tradition and heritage preservation | 1º |

| Prestige and reputation | 2º |

| Income and life quality benefits | 3º |

| Enabling other business opportunities | 4º |

| Institutions Supporting the GI | Cooperative | Producers |

|---|---|---|

| SEBRAE | 1º | 1º |

| Universities (Teaching and Research Institutions) | 2º | 2º |

| Agriculture Departments (Municipal and State) | 4º | 3º |

| MAPA/INPI | 3º | 4º |

| Technical Assistance and Rural Extension Companies | 5º | 5º |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saldanha, C.B.; Silva, D.T.; Martins, L.O.S.; Fraga, I.D.; Silva, M.S. Sustainability of the Origin Indication of Sugar Cane Spirit from Abaíra Microregion, Bahia, Brazil Under the Aegis of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2024, 16, 10880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410880

Saldanha CB, Silva DT, Martins LOS, Fraga ID, Silva MS. Sustainability of the Origin Indication of Sugar Cane Spirit from Abaíra Microregion, Bahia, Brazil Under the Aegis of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability. 2024; 16(24):10880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410880

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaldanha, Cleiton Braga, Daliane Teixeira Silva, Luís Oscar Silva Martins, Igor Dantas Fraga, and Marcelo Santana Silva. 2024. "Sustainability of the Origin Indication of Sugar Cane Spirit from Abaíra Microregion, Bahia, Brazil Under the Aegis of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)" Sustainability 16, no. 24: 10880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410880

APA StyleSaldanha, C. B., Silva, D. T., Martins, L. O. S., Fraga, I. D., & Silva, M. S. (2024). Sustainability of the Origin Indication of Sugar Cane Spirit from Abaíra Microregion, Bahia, Brazil Under the Aegis of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability, 16(24), 10880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162410880