4-Years into the Pandemic Impacts: A Holistic Reflection and Educational Lessons Learnt in the Tourism and Agriculture Sectors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Significance of the Study

1.4. Research Questions

- (a)

- What were the major economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and agriculture sectors over the past four years?

- (i)

- This question originates from the desire to assess and understand the economic effect of the pandemic. Tourism and agriculture, as essential components of the world’s economy, necessitate an in-depth grasp of financial disturbances to analyze their long-term repercussions. The four-year timeline provides for a thorough examination of trends, variations, and long-term impacts, providing a solid foundation for the study.

- (b)

- What were the most effective adaptation techniques demonstrated, and how did each industry cope with the challenges posed by the pandemic?

- (ii)

- The unexpected advent of the pandemic spurred companies to creativity and adaptability. This question seeks to recognize and analyze various coping techniques, providing significant insights that can inform best practices for handling future crises, especially among sectors exposed to external challenges.

- (c)

- How successful were the policy initiatives that were set forth to assist in the revival of both industries?

- (iii)

- The basis for this question is the need to carry out a detailed assessment of the successful implementation of strategies while offering evidence-based insights to guide the formulation of future policy frameworks.

- (d)

- To what extent has interdisciplinary research into tourism and agriculture managed to bridge significant knowledge gaps?

- (iv)

- Tourism and agriculture are highly interrelated, with agriculture often providing support to tourism through food supply chains. This question originates from the realization that holistic approaches are indispensable for handling nuanced challenges involving multiple sectors. Examining the scope of these studies offers perspective on advances made in addressing knowledge gaps while recognizing prospects for further investigations.

- (e)

- What valuable long-term lessons concerning crisis management would be acquired to strengthen resiliency in the tourism and agriculture industries in the wake of a future pandemic?

- (v)

- Crises usually highlight inadequacies and the potential for transformation. This question seeks to discover long-term pandemic lessons, particularly focusing on resiliency and preparation techniques. It is associated with the overarching goal of providing valuable guidance for effectively dealing with future global crises.

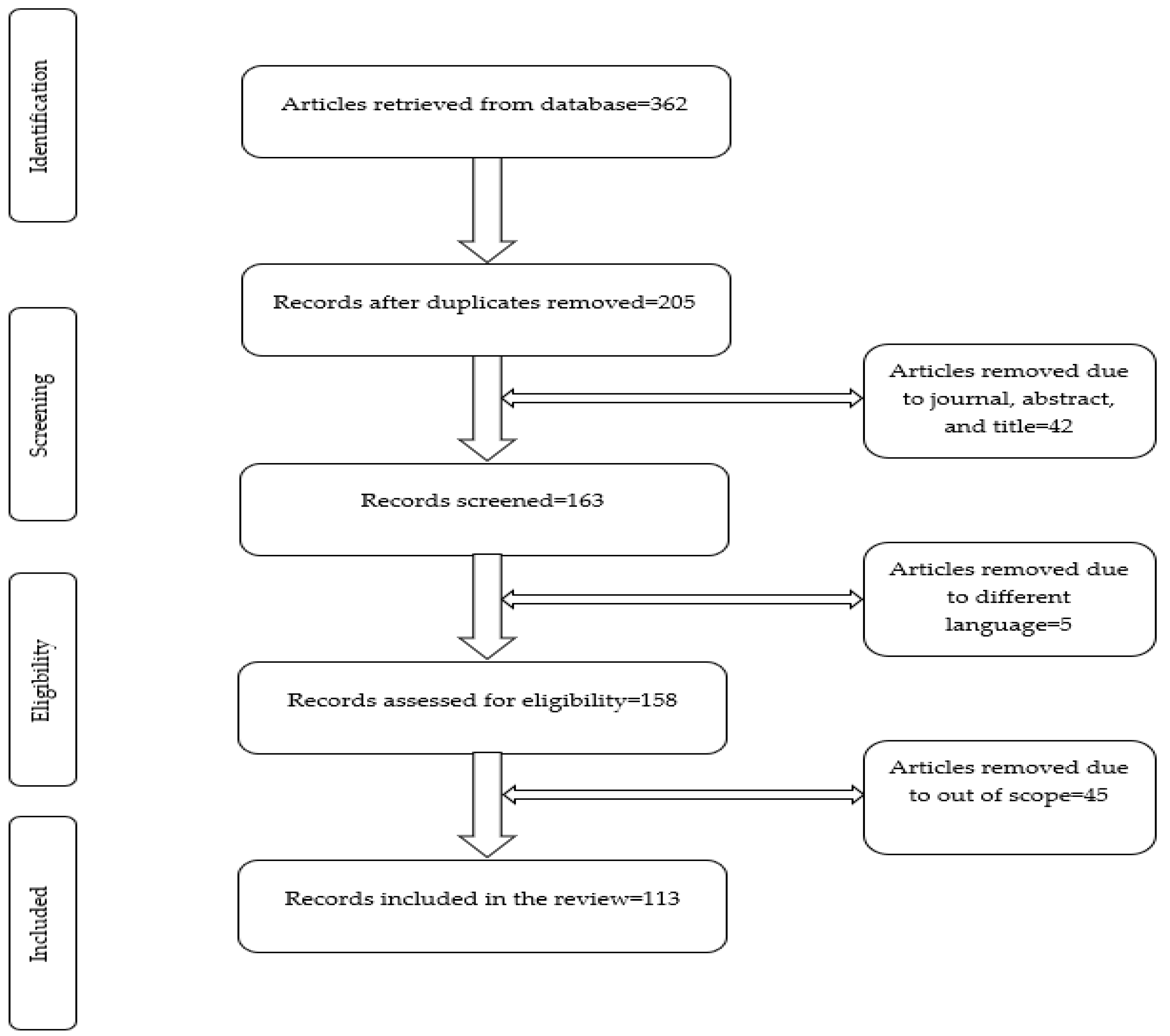

1.5. Methodology

1.5.1. Search Strategy

1.5.2. Selection Process

1.5.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

1.5.4. Models Reviewed

1.6. The Interdependence Between Tourism and Agriculture

2. Thematic Discussion

2.1. Overview of Tourism Industry

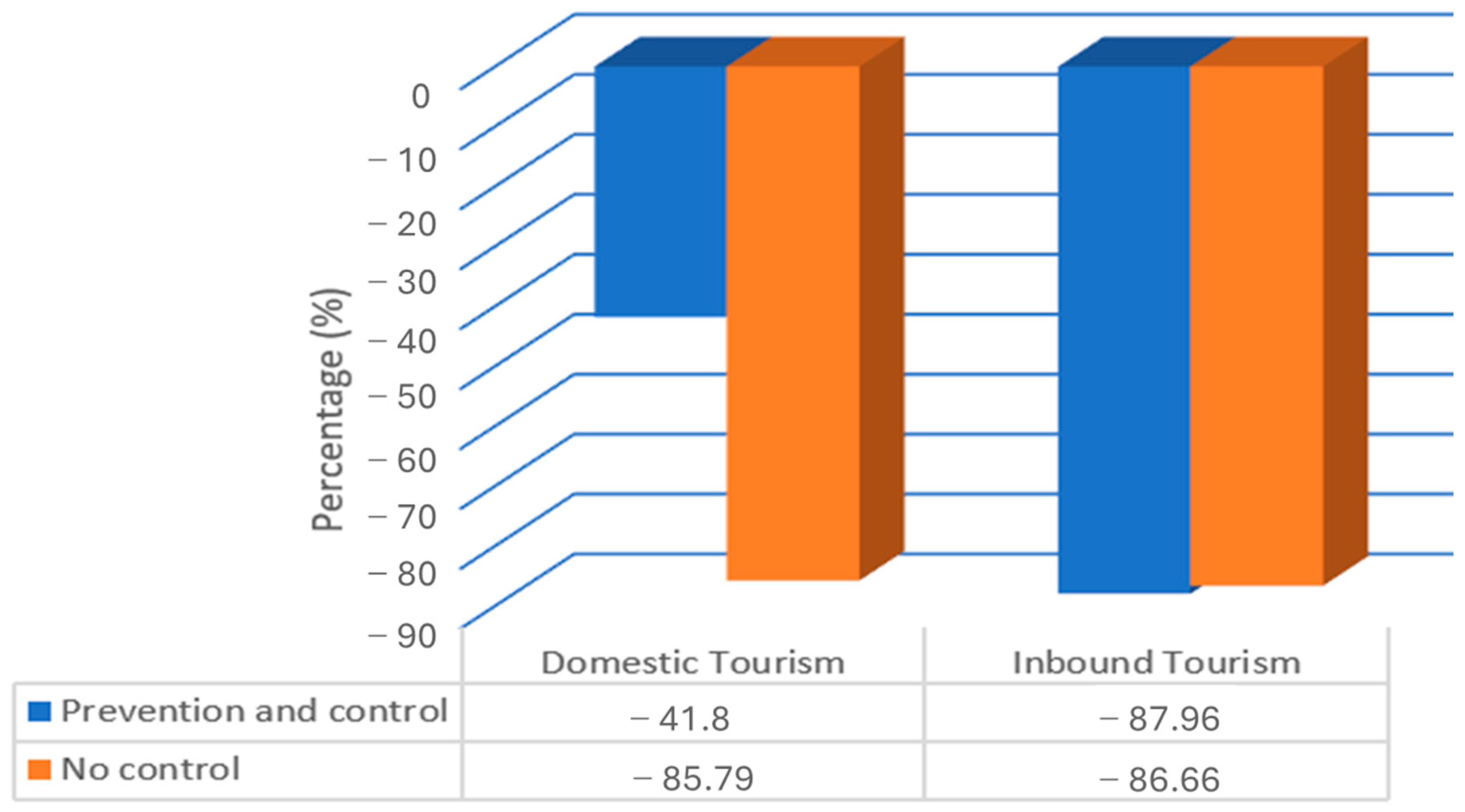

2.1.1. Consequences of the Pandemic on Tourism Industry

2.1.2. Behavioral Attitude of Tourists and Consumption Patterns

2.1.3. Trends in the Tourism Sector

2.1.4. Technological Advancement in the Tourism Industry

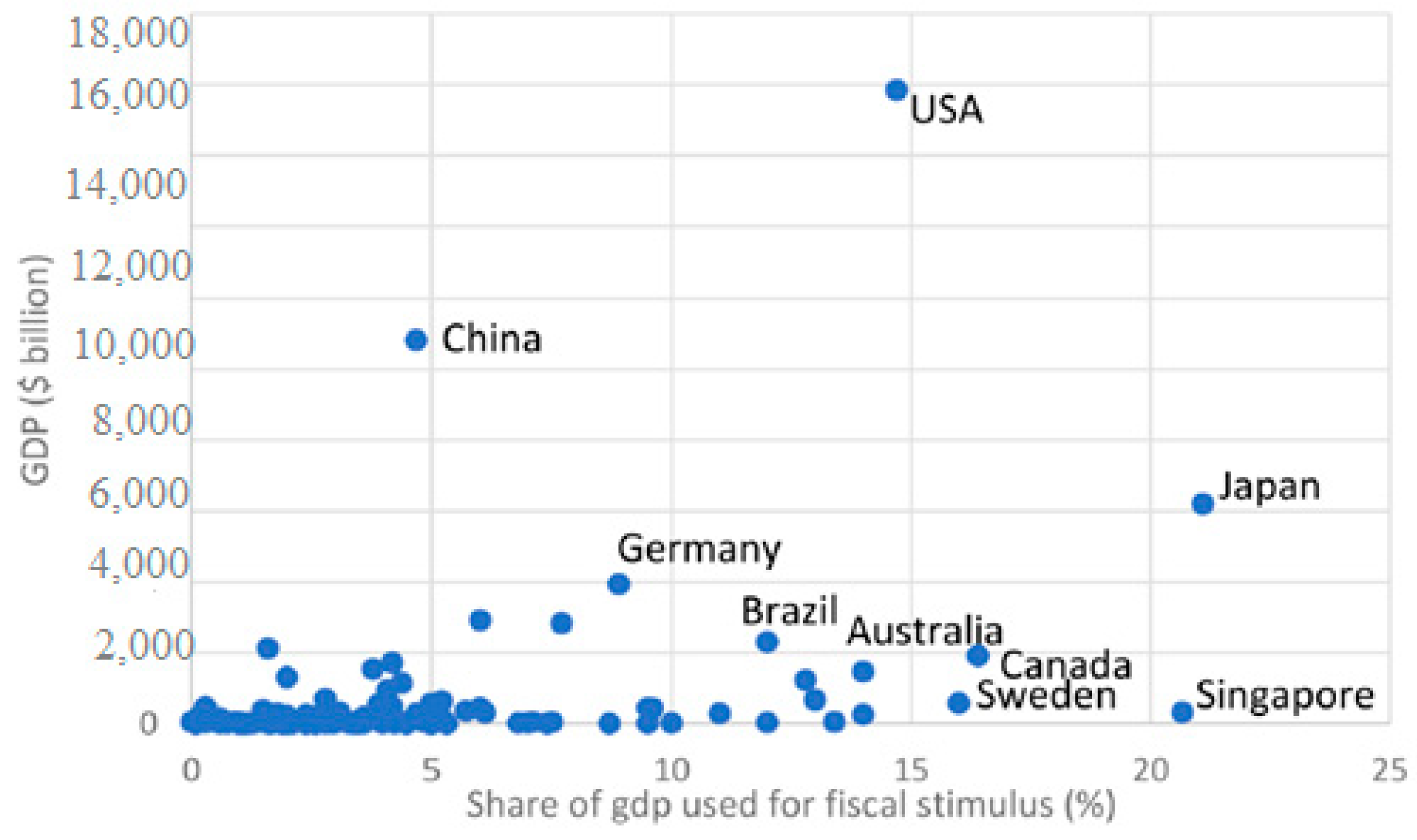

2.1.5. Governments’ Response to COVID-19

2.2. Overview of Agriculture Industry

2.2.1. Main Implications of the Crisis for Food and Livestock Production

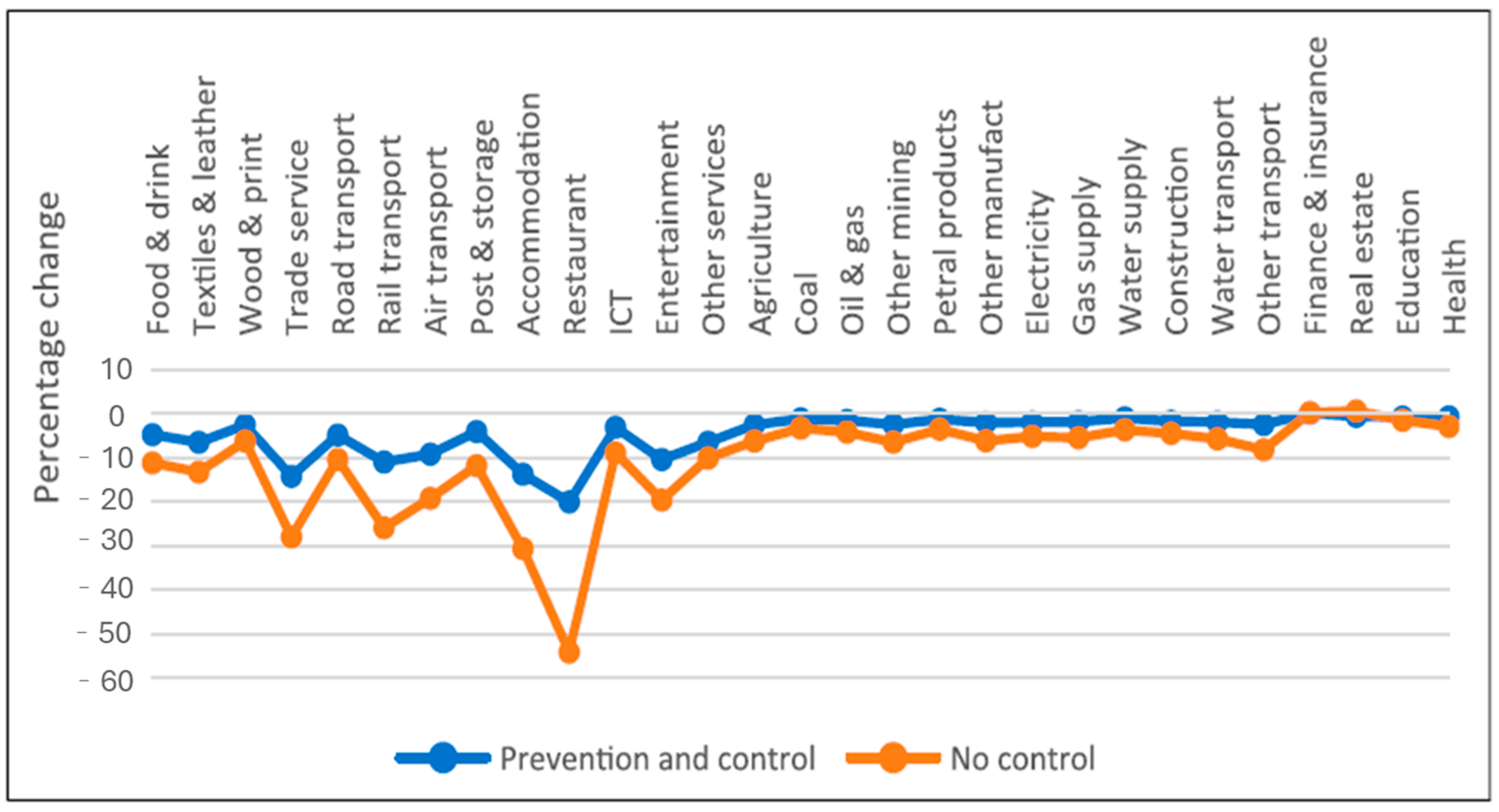

2.2.2. Agricultural Production Disrupted by Prevention and Control Measures

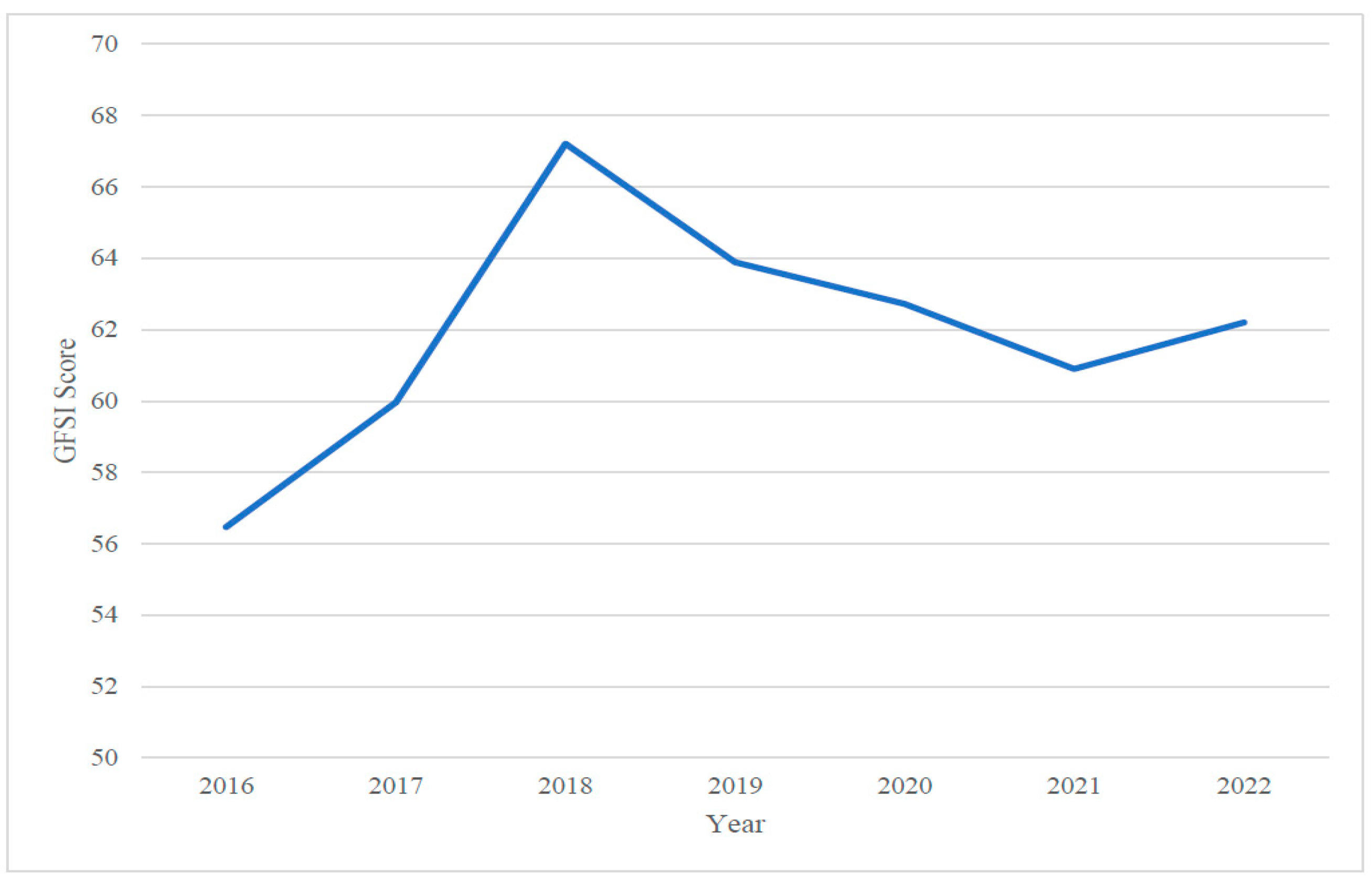

2.2.3. The Future of Agri-Food Systems and Food Security in Post-Pandemic

2.2.4. Opportunities Arising Due to COVID-19 in the Agri-Food Supply Chain

2.2.5. Government Responses to the Agriculture Sector

2.3. “Post-Pandemic Reality” vs. “Resuming Normalcy” vs. “Integrating Both Approaches”

2.4. Key Reflections on Tourism and Agriculture Industries

2.4.1. Tourism Industry

2.4.2. Agriculture Industry

2.5. Implementing Lessons Learnt from COVID-19 in Facing Future Pandemic

2.5.1. Tourism Industry

Hybrid Tourism Models

Blockchain for Health Credentials

Policy Advocacy and Collaboration

Self-Sufficient Tourism Models

Smart Infrastructure

Hyper-Localization

Adaptive Travel Bubbles

Predictive Travel Approach

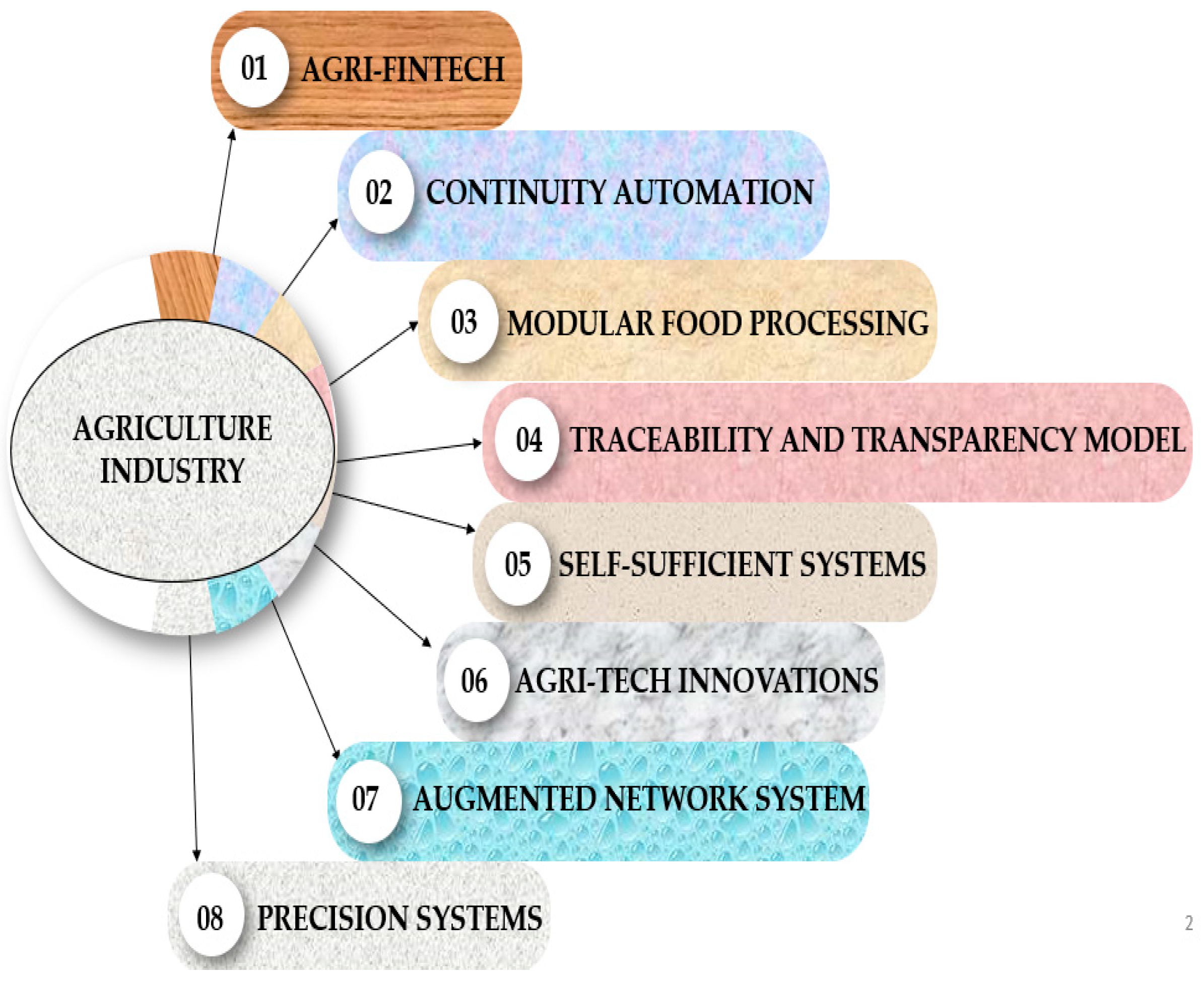

2.5.2. Agriculture Industry

Agri-Fintech

Continuity Automation

Modular Food Processing

Traceability and Transparency Model

Self-Sufficient Systems

Agri-Tech Innovations

Augmented Network System

Precision Systems

3. Implications

3.1. Tourism Industry

3.2. Agriculture Industry

4. Limitations

5. Directions and Propositions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadevall, A. Pandemics past, present, and future: Progress and persistent risks. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e179519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, A.; Kamel, M. Coronaviruses in humans and animals: The role of bats in viral evolution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19589–19600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, V.H.; Isacco, C.G.; Nguyen, K.C.D.; Le, S.H.; Tran, D.K.; Nguyen, Q.V.; Pham, H.T.; Aityan, S.; Pham, S.T.; Cantore, S.; et al. Rapid and sensitive diagnostic procedure for multiple detection of pandemic Coronaviridae family members SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and HCoV: A translational research and cooperation between the Phan Chau Trinh University in Vietnam and University of Bari “Aldo Moro” in Italy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7173–7191. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.Q.; Huang, T.; Wang, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.P.; Liang, Y.; Huang, T.B.; Zhang, H.Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantrais, L.; Allin, P.; Kritikos, M.; Sogomonjan, M.; Anand, P.B.; Livingstone, S.; Williams, M.; Innes, M. COVID-19 and the digital revolution. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2021, 16, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, Z.; Habibi, H.; Mohammadi, M.A. The potential impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese GDP, trade, and economy. Economies 2022, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D. COVID-19 lockdowns throughout the world. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M.; Sousa, N.; Silva, R. Reviewing COVID-19 literature on business management: What it portends for future research? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N.; Jorge, F.; Teixeira, M.S.; Losada, N.; Melo, M.; Bessa, M. An exploratory study about the effect of COVID-19 on the intention to adopt virtual reality in the tourism sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zopiatis, A.; Pericleous, K.; Theofanous, Y. COVID-19 and hospitality and tourism research: An integrative review. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raki, A.; Nayer, D.; Nazifi, A.; Alexander, M.; Seyfi, S. Tourism recovery strategies during major crises: The role of proactivity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, N.K. Epidemiologic surveillance for controlling COVID-19 pandemic: Types, challenges and implications. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lame, G. Systematic literature reviews: An introduction. In Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1633–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Carrión, P.V.; González-González, C.S.; Aciar, S.; Rodríguez-Morales, G. Methodology for systematic literature review applied to engineering and education. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 1364–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W65–W94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L., 2nd; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. Science and technology for sustainable development special feature: A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, C.P.; Turner, S.; Norman, E.; Stillson, K. Promoting resilience strategies: A modified consultation model. Child. Sch. 1996, 18, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Pathirage, C.; Fernando, T. Measuring community disaster resilience at local levels: An adaptable resilience framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.G.; Busemeyer, J.R. Decision making under risk and uncertainty. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 1, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, M.D.; Rickman, D.S. Computable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling for regional economic development analysis. Reg. Stud. 2008, 44, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandizzo, P.L.; Ferrarese, C. Social accounting matrix: A new estimation methodology. J. Policy Model. 2015, 37, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, S.; Mishra, H.G.; Chib, S. Psychological impact of covid-19 crises on students through the lens of Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettman, J.R. Perceived risk and its components: A model and empirical test. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 10, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P.; Teoh, S.; Salazar, N.B.; Mostafanezhad, M.; Pung, J.M.; Lapointe, D.; Desbiolles, F.H.; Haywood, M.; Hall, C.M.; Clausen, H.B. Reflections and discussions: Tourism matters in the new normal post COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R. Linkages between tourism and agriculture in Mexico. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ruan, Q.; Huang, S.S.; Lan, T.; Wang, Y. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on tourists’ real-time on-site emotional experience in reopened tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Meng, X.; Siriwardana, M.; Pham, T. The impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2021, 28, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citaristi, I. World Tourism Organization—UNWTO. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 404–407. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F. Travel anxiety, risk attitude and travel intentions towards “travel bubble” destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Altschuler, B.; Liang, Z.; Li, X.R. Monitoring the global COVID-19 impact on tourism: The COVID-19 tourism index. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 90, 103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzos, S.; Samitas, A.; Spyridou, A.E. Tourism demand and the COVID-19 pandemic: An LSTM approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Polyzos, S.; Huan, T.C.T. The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-18 tourism recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uğur, N.G.; Akbıyık, A. Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škare, M.; Streimikiene, D.; Skare, D. Measuring carbon emission sensitivity to economic shocks: A panel structural vector autoregression 1870–2016. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 44505–44521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaipuria, S.; Parida, R.; Ray, P. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism sector in India. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 46, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Prabhakar, D. COVID-19 Non-Tariff Measures: The Good and the Bad, Through a Sustainable Development Lens; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Y.; Ou, J.; Wang, D.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Guan, D.; Hubacek, K. Impacts of COVID-19 and fiscal stimuli on global emissions and the Paris Agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 11, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, L.P.; Chin, M.Y.; Tan, K.L.; Phuah, K.T. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2735–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.C.; Prayag, G.; Fieger, P.; Dyason, D. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.; Oz-Yalaman, G. Explaining different types of undeclared work: Lessons from a 2019 Eurobarometer survey. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lai, F.T.T.; Yan, V.K.C.; Cheng, F.W.T.; Cheung, C.L.; Chui, C.S.L.; Li, X.; Wan, E.Y.F.; Wong, C.K.H.; Hung, I.F.N.; et al. Comparing hybrid and regular COVID-19 vaccine-induced immunity against the Omicron epidemic. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Hu, Z. Rural China under the COVID-19 pandemic: Differentiated impacts, rural–urban inequality and agro-industrialization. J. Agrar. Chang. 2021, 21, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, M.; Chang, L. Evaluating economic recovery by measuring the COVID-19 spillover impact on business practices: Evidence from Asian markets intermediaries. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2023, 56, 1629–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiripour, A.; Rahimi, E.; Shabanpour, R.; Mohammadian, A.K. How is COVID-19 reshaping activity-travel behavior? Evidence from a comprehensive survey in Chicago. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Ivanov, I.K.; Ivanov, S. Travel behaviour after the pandemic: The case of Bulgaria. Anatolia 2020, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ramos, I.P.; Lazo, M.; Schnake-Mahl, A.; Li, R.; Martinez-Donate, A.P.; Roux, A.V.D.; Bilal, U. COVID-19 outcomes among the Hispanic population of 27 large US cities, 2020–2021. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairo-Castineira, E.; Clohisey, S.; Klaric, L.; Bretherick, A.D.; Rawlik, K.; Pasko, D.; Walker, S.; Parkinson, N.; Fourman, M.H.; Russell, C.D.; et al. Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in COVID-19. Nature 2021, 591, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Measuring risks and vulnerability of tourism to the COVID-19 crisis in the context of extreme uncertainty: The case of the Balearic Islands. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Gong, J.; Gao, B.; Yuan, P. Impacts of COVID-19 on tourists’ destination preferences: Evidence from China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anh, P.; Huy, D.T.N. Internet benefits and digital transformation applying in boosting tourism sector and forecasting tourism management revenue. Webology 2021, 18, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, N.; Mahroof Khan, M.; Ashraf, S.; Hashmi, M.S.; Khan, M.M.; Hishan, S.S. Post-COVID-19 tourism: Will digital tourism replace mass tourism? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.H.H.; Chan, C.P.; Jin, D.Y. Lessons learned from the fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong in early 2022. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, G.; Ullah, I.; Singh, J.; Arumungam, T. Digital Tourism: A Possible Revival Strategy for Malaysian Tourism Industry after COVID-19 Pandemic. Electron. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Seyfi, S. COVID-19 pandemic, tourism and degrowth. In Degrowth and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 220–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Fuchs, M.; Baggio, R.; Hoepken, W.; Law, R.; Neidhardt, J.; Pesonen, J.; Zanker, M.; Xiang, Z. e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudik, A.; Mohaddes, K.; Raissi, M. COVID-19 fiscal support and its effectiveness. Econ. Lett. 2021, 205, 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook Update, June 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/06/24/WEOUpdateJune2020/https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-andcovid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Tsionas, M.G. COVID-19 and gradual adjustment in the tourism, hospitality, and related industries. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1828–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Ung, C.O.L.; Pinto, J.F. Living with COVID-19 and sustaining a tourism recovery—Adopting a front-line collaborative response between the tourism industry and community pharmacists. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W. Disaster collaboration in tourism: Motives, impediments and success factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, B.N. Economic impact of government interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: International evidence from financial markets. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 27, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imtyaz, A.; Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. Analysing governmental response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 10, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balistreri, E.; Baquedano, F.; Beghin, J.C. The impact of COVID-19 and associated policy responses on global food security. Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.; Countryman, A.M. The importance of agriculture in the economy: Impacts from COVID-19. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Han, F.; Li, K.; Wang, Y. Vegetable production under COVID-19 pandemic in China: An analysis based on the data of 526 households. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2854–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.Y.; Wang, C.W. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on vegetable production and countermeasures from an agricultural insurance perspective. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2866–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Shishodia, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Belhadi, A. Agriculture supply chain risks and COVID-19: Mitigation strategies and implications for the practitioners. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 27, 2351–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, M.A.; Ridzwan, C.R.; Oyebamiji, Y.O.; Usaizan, N.; Abioye, A.E.; Biola, I.F.; Bamiro, N.B.; Omowunmi, A.K.; Luqman, H. Disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic on the agri-food sector: A systematic review of its implications in post-pandemic and future of food security. AIMS Agric. Food 2024, 9, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielechowski, M.; Zając, A.; Czech, K. Credit Financing of MICRO-Enterprises and Farmers by Commercial and Cooperative Banks in Poland: Does the use of Investment and Working Capital Loans Change During The COVID-19 pandemic? Optim. Econ. Stud. 2023, 3, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielechowski, M.; Jędruchniewicz, A.; Kotyza, P. Instruments Mitigating the Negative Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Agriculture. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2024, 23, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, M.; Zhong, Y. Rising concerns over agricultural production as COVID-19 spreads: Lessons from China. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, A.; Balakrishnan, A.; Jacob, M.M.; Sillanpää, M.; Dayanandan, N. Global impact of COVID-19 on agriculture: Role of sustainable agriculture and digital farming. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 42509–42525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochtis, D.; Benos, L.; Lampridi, M.; Marinoudi, V.; Pearson, S.; Sørensen, C.G. Agricultural workforce crisis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.X.; Lai, X.D.; Long, W.J.; Gao, L.L. The short-and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family farms in China–Evidence from a survey of 2324 farms. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2877–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.B.; Liu, C.Q.; Zhao, Y.F.; Kitsos, A.; Cannella, M.; Wang, S.K.; Han, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dairy industry: Lessons from China and the United States and policy implications. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2903–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Schwartz, M.; Ghosh, D.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and retail grocery management: Insights from a broad-based consumer survey. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, X.-H. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumers’ food safety knowledge and behavior in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2926–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

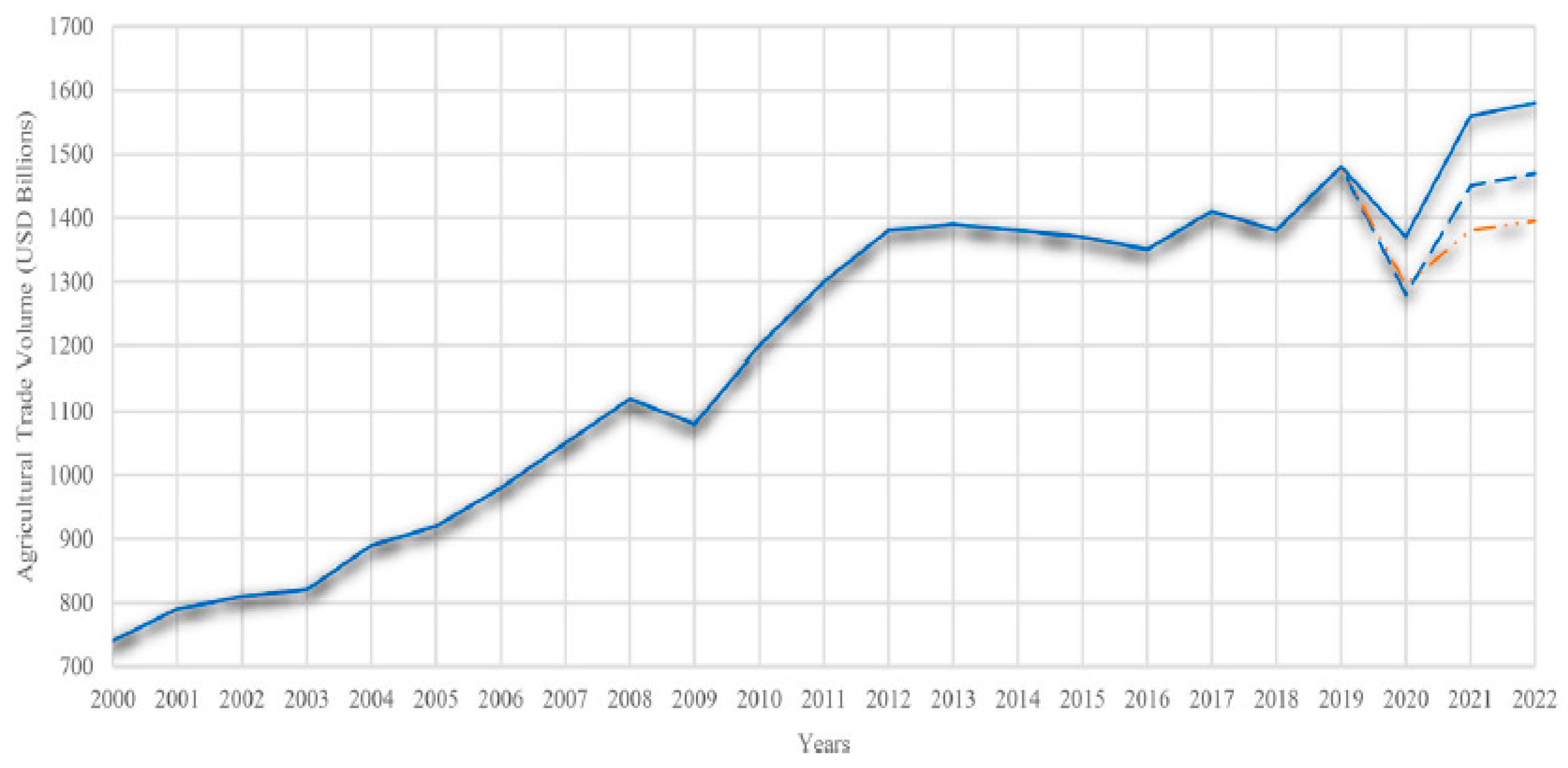

- Lin, B.X.; Zhang, Y.Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural exports. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2937–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO (World Trade Organization). Trade Set to Plunge as COVID-19 Pandemic Upends Global Economy. Geneva. 2020. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Wei, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Y.; Huang, G.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X. Resilience analysis of global agricultural trade. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 51, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Crush, J.; Si, Z.; Scott, S. Emergency food supplies and food security in Wuhan and Nanjing, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a field survey. Dev. Policy Rev. 2022, 40, e12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafar, A.A. Statistics of rice farming activities during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: The case of Niger State, Nigeria. Sarhad J. Agric. 2022, 38, 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Roubík, H.; Lošťák, M.; Ketuama, C.T.; Procházka, P.; Soukupová, J.; Hakl, J.; Karlík, P.; Hejcman, M. Current coronavirus crisis and past pandemics-What can happen in post-COVID-19 agriculture? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, P.; Doherty, B.; Heron, T. Vulnerability of the United Kingdom’s food supply chains exposed by COVID-19. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torero, M. Without food, there can be no exit from the pandemic. Nature 2020, 580, 588–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S. Robotization and Economic Development; Routledge: Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Shao, J.; Liang, S.; Yu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, C. The long-term health outcomes, pathophysiological mechanisms and multidisciplinary management of long COVID. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiet, A.; Dufays, F.; Friedel, S.; Staessens, M. The resilience of the cooperative model: How do cooperatives deal with the COVID-19 crisis? Strateg. Chang. 2021, 30, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, A. Co-operative learning and resilience to COVID-19 in a small-sized South African enterprise. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentsiev, A.U.; Aygumov, T.G.; Amirova, E.F. The Role Of Digital Technologies In The Formation Of The Digital Economy. In European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; Kovalev, I.V., Voroshilova, A.A., Budagov, A.S., Eds.; European Publisher: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1870–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo, L.S.; Fiore, M.; Galati, A. How the COVID-19 pandemic is changing online food shopping human behaviour in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, G.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D. The determinants of panic buying during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P. Antecedents and consequences of panic buying: The case of COVID-19. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jin, Y.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Identifying emergence process of group panic buying behavior under the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Aiyub, A.S.; Greig, T.; Naidu, S.; Sewak, A.; Sharma, S. Exploring panic buying behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: A developing country perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 1587–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.J. Impact of COVID-19 on consumer buying behavior toward online shopping in Iraq. Econ. Stud. J. 2020, 18, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hidrobo, M.; Kumar, N.; Palermo, T.; Peterman, A.; Roy, S. Gender-Sensitive Social Protection: A Critical Component of the COVID-19 Response in Low-And Middle-Income Countries; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner, J.M.; Mindermann, S.; Sharma, M.; Johnston, D.; Salvatier, J.; Gavenčiak, T.; Stephenson, A.B.; Leech, G.; Altman, G.; Mikulik, V.; et al. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science 2021, 371, eabd9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, H. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations—FAO. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Pandemics | Dissemination |

|---|---|---|

| 165–190 | Antonine Plague | Europe, Middle East |

| 550 AD | Plague of Justinian”—bubonic plague | Europe and West Asia |

| 590 AD | “Roman plague” bubonic plague | Italy, France, Spain Byzantine Empire |

| 700 AD | plague (unspecified infection) * | British Isles, West Asia, Middle East |

| 736 AD | smallpox | East Asia |

| 993–996 AD | plague (unspecified infection) * | Continental Europe, British Isles |

| 1031–1033 AD | plague (unspecified infection) * typhus | Europe, Middle East |

| 1193–1196 AD | plague fever (unspecified infection—pulmonary plague?) | Europe |

| 1221–1224 AD | plague (unspecified infection) | Europe |

| 1311–1318 AD | plague (unspecified infection) * “acute fever” (in the British Isles, unspecified infection) | Central Europe, West Europe |

| 1346–1390 AD | “Black Death” pandemic bubonic plague, pulmonary plague (1367 in Germany) several waves | Europe, Asia |

| 1485–1551 AD | Sweating sickness (unspecified infection, possibly hantavirus) | The British Isles and continental Europe |

| 1520–1576 AD | smallpox „ cocoliztli (possibly salmonella?) | Mexico and Central America |

| 1596 AD | Cocoliztli (possibly salmonella?) | East Europe, India, Asia |

| 1629–1631 AD | bubonic plague | Russia, Middle East |

| 1816–1824 AD | cholera | Europe, Asia |

| 1846 AD | cholera | Russia, Europe |

| 1889–1890 AD | influenza | Europe, America |

| 1916–1920 AD | “Spanish flu”—influenza | Worldwide |

| 1918–1922 AD | Typhus | East Europe |

| 1957–1958 AD | “Asian flu”—influenza | Worldwide |

| 1968–1970 AD | “Hong Kong flu”—influenza | Worldwide |

| 2003 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) | Worldwide |

| 2012 | Middle East Respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) | Worldwide |

| Condition | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Literature type | Research articles | Conference papers, book chapter, |

| Country | Worldwide | |

| Language preference | English | Other languages |

| Year | 2019–2024 | 2018 and earlier |

| Review Type | Peer-reviewed | Non-Peer reviewed |

| Relevancy | Tourism, and agriculture industries | Other industries |

| Country | The Response of the Government and Industry to COVID-19 |

|---|---|

| Colombia | A line of communication has been established with the international tourism agencies in Latin America and tourism organizations to exchange information regarding standards of excellence. |

| Belgium | The cancellation of a stimulus package could result in the provision of a credit voucher for the same value rather than a refund that is good for at least a year. |

| Canada | To help alleviate the financial burden on indigenous tourism firms, the Canadian Experiences Fund (CEF) has granted a sum of one million Canadian dollars (CAD). |

| Estonia | An EUR 25 million “aid package” has been put together to help the tourist industry by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications, Enterprise Estonia, the Kredex Foundation (a public financing institution for Estonian firms), and others. |

| United States | The government has unveiled an incentive programme for all enterprises worth USD 2 trillion, with tourism being the highest priority. |

| Spain | The Secretariat of State for Tourism has given loans with the option to postpone the payment of both interest and principal. |

| Poland | In an effort to get tourists to make optimal use of their predetermined assistance, the Polish Tourism Organization launched the “Poland Don’t Cancel, Postpone” campaign. |

| United Kingdom | The United Kingdom government and Visit Britain are currently collaborating on a recovery scheme to promote tourism in the United Kingdom following the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Singapore | The Singapore Tourism Board (STB) has formed a Tourism recuperation Action Task Force (TRAC) that will assist the sector in formulating and carrying out strategies. |

| Japan | In order to promote popular tourist spots, improve the travel atmosphere, and attract more international visitors, the Japanese Tourism Agency has allocated USD 2.2 billion to recover the tourism industry. |

| Republic of Korea | The Korean government has recently implemented measures to boost the tourism industry, including tax cuts, job creation, and monetary support. |

| South Africa | Small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in the hotel and tourist industry have access to an assistance grant worth around $11 million in South Africa. |

| Switzerland | In order to strengthen Switzerland Tourism (ST) in 2020 and 2021, the Swiss Parliament has suggested an additional CHF 40 million in government support. |

| Italy | In an effort to restore Italy’s tourism status, the government has extended a rescue package to the tourism industry worth 4 billion Euros. |

| Germany | An informative webpage regarding the consequences of COVID-19 on the tourism business has been created by the Federal Government Centre of Excellence for Tourism to boost the industry. |

| European union | The European Union (EU) has eased government support regulations, provided financial relief, and bolstered the travel and tourism industry’s liquidity. |

| Greece | A committee to oversee coronavirus crises has been formed by the Tourist Ministry. |

| Costa Rica | For organizations facing financial challenges, the Costa Rican Tourism Institute has provided a three-month tax respite on plane ticket sales and money earned per tourist. |

| Brazil | For small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the tourist sector, the National Development Bank has provided an operational loan. Additionally, a relief package for airlines has been put together. |

| Austria | Tourists in Austria can now take advantage of a new coronavirus package spearheaded by the joint efforts of the country’s agriculture, regions, and tourist ministry and the Austrian Bank for tourist Development. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Adu-Poku, K.A.; Appiah, D. 4-Years into the Pandemic Impacts: A Holistic Reflection and Educational Lessons Learnt in the Tourism and Agriculture Sectors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310617

Yu Y, Zhang F, Adu-Poku KA, Appiah D. 4-Years into the Pandemic Impacts: A Holistic Reflection and Educational Lessons Learnt in the Tourism and Agriculture Sectors. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310617

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yang, Fan Zhang, Kofi Asamoah Adu-Poku, and Desmond Appiah. 2024. "4-Years into the Pandemic Impacts: A Holistic Reflection and Educational Lessons Learnt in the Tourism and Agriculture Sectors" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310617

APA StyleYu, Y., Zhang, F., Adu-Poku, K. A., & Appiah, D. (2024). 4-Years into the Pandemic Impacts: A Holistic Reflection and Educational Lessons Learnt in the Tourism and Agriculture Sectors. Sustainability, 16(23), 10617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310617