Abstract

The objective of this study was to identify the determinants of personal norm and to measure the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior as well as a possible mediating role of consumer LOHAS orientation in the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior in the hospitality context. A field study was designed to measure the hypothesized effects, and 418 consumers who regularly purchase summer holidays in hotels were included in the survey. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed in order to test the proposed hypotheses. The results confirm that social norm, the ascription of responsibility, and the attitude towards green purchasing behavior are the determinants of personal norm. Personal norm is found to affect both the green purchasing behavior and the LOHAS orientation of consumers. The results of the study also confirmed that LOHAS orientation does not mediate the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior due to the dominance of personal norm’s effect on LOHAS orientation. Academic as well as managerial implications are provided in the Discussion. The Conclusion provides the most important academic and practical contributions of the study, limitations related to the generalizability of the findings, and recommendations for future studies.

1. Introduction

The increasing consumption of products and services in the last couple of decades has resulted in the exhaustion of natural resources, the deterioration of ecosystem services, and the degradation of the environment [1]. Earth Overshoot Day, an indicator calculated by the Global Footprint Network, is the date when the demand of the human population for ecological resources and services exceeds the regeneration capacity of Earth in the same year; the 1st of August was announced as the Earth Overshoot Day for 2024 [2]. According to the Living Planet Report (2010), which was prepared by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), humanity will need a second Earth by the year 2030 in the case of continued excessive demand for and consumption of natural resources [3]. The recent Living Planet Report (2022) clearly indicates that humanity is experiencing a global double emergency crisis of climate and biodiversity [4]. As a reflection of these current issues, there is increasing public concern about environmental problems, and in the last couple of years, we have witnessed a rapidly growing sensitivity of consumers to environmental issues, leading to an increasing tendency towards consuming green products and services [5]. Many consumers make green purchases involving eco-friendly products and services to show their commitment to environmental protection, and they even pay higher amounts for such eco-products [6,7].

Firms in the hospitality sector, especially hotels, contribute to environmental deterioration through their operations [8]. The operations and services of the industry lead to substantial water, energy, and product consumption [9]. Several statistics related to waste production, carbon emission production, and water usage confirm that the hospitality industry substantially contributes to environmental deterioration. The tourism industry is one of the major contributors to food waste production globally; as a standalone industry, it produces around 9% of total global food waste [10], and hotels generate 79,000 tons of food waste each year [11]. However, the food and beverage sector, a part of the hospitality industry, produces 12% of food waste globally [12]. Based on a report by Deloitte (2024), the hospitality sector was also responsible for the generation of 3% of total global carbon emissions for the year 2022 [13]. Based on the Global Hotel Decarbonisation Report (2017) by the Sustainable Hospitality Alliance, the greenhouse gas emissions of the hotel industry should be reduced by 66% from 2010 levels by 2030 and 90% by 2050 in order to keep carbon emission production constant based on industrial growth projections [14]. Water consumption is also an important area in which the hotel industry contributes to environmental deterioration. According to the Water Stewardship for Hotel Companies report (2018) by the Sustainable Hospitality Alliance, an average hotel guest uses eight times more water than a household user [15]. As a response to increasing pressure from the wider community, as a result of their financial motivations and as a part of their responsible behavior towards the environment, increasing numbers of hotels incorporate green management practices into their operations [16,17,18]. These green practices involve minimizing their environmental impact by reducing waste and using sustainable resources and supplies, ultimately leading to a more pro-environmental business model that supports environmental health [19,20]. Such hotels encourage their customers to actively participate in and support environmentally friendly practices [21]. In turn, several studies in the hospitality sector have confirmed that a growing proportion of consumers prefer hotels with green management practices [22,23]. The behavior of such consumers is determined by their sense of moral obligation, namely personal norm, to take environmentally friendly actions [24]. An important segment of consumers, who are sensitive to health and sustainability issues, are called LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability). This segment of consumers has an ecological orientation and focuses on the environmental impact of products and services by taking into consideration the whole life cycle [25]. These consumers show a higher tendency to purchase green products and services compared to ordinary consumers [26]. Thus, it is expected that consumers with high levels of LOHAS characteristics will prefer hotels with green management practices compared to ordinary consumers.

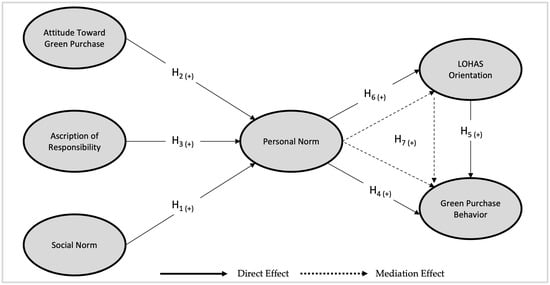

A careful review of the literature in the hospitality context yields a considerable number of studies focused on sustainability issues. However, studies that combine sustainability concepts, including green purchasing behavior, with the lifestyle orientation of consumers constitute the missing part of the body of research in this field [27]. This study utilized the theory of green purchasing behavior proposed by Han (2020) to identify the determinants of personal norm and its effect on green purchasing behavior [24]. Specifically, this study investigated the effects of three important determinants—attitudes toward green purchasing, the ascription of responsibility, and social norm—on personal norm. The study extends the theoretical framework and contributes to the existing literature by investigating the mediating role of the LOHAS orientation level of consumers in the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior. Initial studies conducted in the context of the LOHAS orientation of consumers mainly focused on the definition [28] and conceptualization of the LOHAS consumer segment [29]. Further studies in the literature investigated the effects of LOHAS orientation on green purchasing behavior [30]; these studies mainly focused on several contexts including retail [31], hospitality [32,33,34], and fashion [35]. There is a lack of studies in the LOHAS research stream that include the LOHAS orientation construct in green purchasing behavior models as a factor that shapes the effects of several antecedents on green purchasing behavior. Thus, while personal norm was identified as a determinant of green purchasing behavior in previous related studies, there is a lack of studies investigating the same effect with the inclusion of consumer lifestyle factors such as LOHAS. This study differs from the existing LOHAS orientation studies by integrating the construct into the green purchasing behavior mechanism as a mediating factor. This is expected to contribute to the existing literature and to generate valuable insights for practitioners in the industry by exploring the interactive mechanism between the personal norm, LOHAS orientation, and green purchasing behavior in the context of hospitality. More specifically, the results are expected to enhance the understanding of how the LOHAS orientation of consumers will shape the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior, which, in turn, is expected to help practitioners in the hospitality sector to generate effective strategies to attract consumers by considering the LOHAS orientation level of consumers. Thus, the investigation of the mediation effect of LOHAS orientation fills a gap in the current literature by considering a lifestyle orientation factor in the effect of personal norm on pro-environmental behavior.

In light of the gaps identified in the current literature, this study aimed to answer the following research questions and eventually contribute to the knowledge base:

- Does social norm in the context of environmental issues contribute to the formation of personal norm in the same context?

- Does the attitude towards green purchasing lead to the formation of personal norm in the context of environmental issues?

- Does the ascription of responsibility in the context of environmental issues lead to the formation of personal norm in the same context?

- Does the existence of personal norm in the context of environmental issues lead to green purchasing behavior?

- Does the LOHAS orientation of consumers lead to involvement in green purchasing behavior?

- Does the existence of personal norm in the context of environmental issues lead to the formation of a LOHAS orientation?

- Does the LOHAS orientation of consumers mediate the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior?

The following section provides a literature review including the theoretical framework as well as the proposed hypotheses related to green purchasing behavior, personal norm and its determinants, the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior, and the mediating effect of LOHAS orientation on the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior. In Section 3, the research methodology is presented with special subsections about the research design, the operationalization of variables, and validity and reliability checks of the constructs employed in the study. In Section 4, hypotheses proposed in the main model and post hoc model are tested, and the results of the analysis are presented. In Section 5, labeled the Discussion, the findings of the study are reviewed and evaluated in terms of the academic literature and practical applications. In terms of the academic literature, the findings of this study are compared with the results of previous studies. In terms of practical applications, insights provided by the results are reviewed, and recommendations are made. In the last section of the paper, the Conclusion, the main contributions of the study are provided from theoretical and practical perspectives. The limitations of the study and recommendations on the subjects of further studies are also provided in this section.

2. Literature Review and Proposed Hypothesis

2.1. Green Purchasing Behavior

The increasing awareness of consumers about anthropogenic risks has led many to become involved in green purchasing behavior as a personal response to help prevent such risks from being realized. Green purchasing behavior involves the purchase and consumption of environmentally friendly products and services and the avoidance of harmful ones [36]. As a prosocial behavior, green purchasing behavior derives from the ethical decision-making domain, which involves the fulfillment of consumers’ eco-friendly needs and wants, to prevent anthropogenic risks [6]. From a theoretical standpoint, this prosocial green purchasing behavior of consumers can be explained with the support of three interrelated theories: the norm activation theory, the values–briefs–norms theory, and the theory of green purchasing behavior [24].

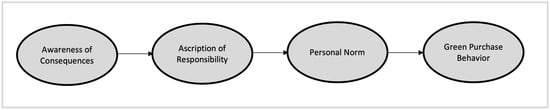

The norm activation theory, which was developed and proposed by Schwartz (1968), explains the motives leading to a prosocial behavior as a function of the awareness of consequences, the acceptance of responsibility, and personal norm [37]. Thus, when there is a high intensity of awareness of consequences and the person feels responsibility for these consequences, personal norms will be generated based on this belief, which eventually leads to a behavior aiming to prevent the negative consequences [38]. The theory suggests that prosocial motives are the main source of behavior rather than self-interested motives. Thus, in the context of green purchasing behavior, norm activation theory provides a good theoretical foundation for investigating and explaining the eco-friendly product and service preferences of consumers [39]. The conceptual model of norm activation theory provided by Han (2015) is reproduced in Figure 1 [40]. As presented in Figure 1, in the context of green purchasing behavior, an awareness of the consequences of an action or situation with regards to environmental issues leads to the generation of responsibility towards the environment, and this feeling of responsibility supports the generation of personal norm regarding the pro-environmental behavior, which in turn is expected to trigger green purchasing behavior.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the norm activation theory.

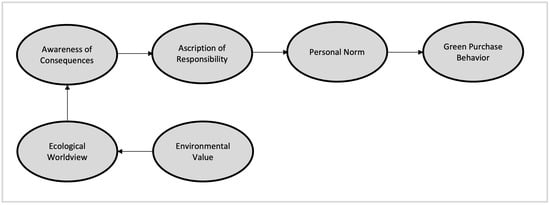

Proposed by Stern et al. (1995), the values–beliefs–norms theory incorporates both values and beliefs to explain prosocial behavior [41]. The theory explains prosocial behavior as resulting from the activation of norms of helping, derived from the personal values of the person, the person’s belief that these values are under threat, and the belief that these values can be restored by taking an action to eliminate the threat [38]. Thus, in the context of green purchasing behavior, the theory of values–beliefs–norms explains eco-friendly behavior as a function of personal values under threat due to anthropogenic risks and the belief that purchasing eco-friendly products and services will restore these values. This theory can be regarded as an extended version of the norm activation theory that is expected to make predictions regarding pro-environmental behavior more accurate [42]. The conceptual model of the values–beliefs–norms theory is reproduced in Figure 2 [40]. As it is presented in Figure 2, in the context of green purchasing behavior, personal environmental values lead to the generation of an ecological worldview, which in turn triggers the chain of reactions described in norm activation theory, ultimately leading to the formation of green purchasing behavior.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the values–beliefs–norms theory.

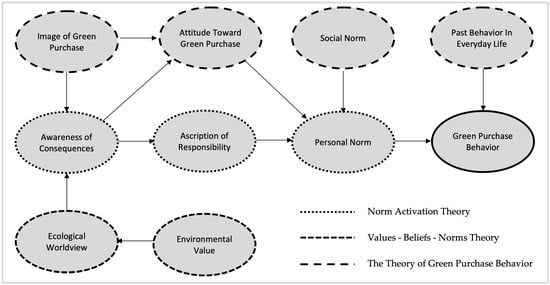

Han (2020) identified a lack of factors for fully explaining eco-friendly behavior and proposed the theory of green purchasing behavior by including other prosocial and pro-environmental factors that are expected to fill this gap [24]. The theory utilizes attitudinal processes [40], social norm [43], image [44], and habitual process [45] as the additional determinants of green purchasing behavior. The theory incorporates the norm activation theory and the values–beliefs–norms theory and explains the formation of personal norm as a function of attitude toward green purchasing, the ascription of responsibility, and social norm. In turn, the theory explains the formation of green purchasing behavior by utilizing personal norm and past behavior in everyday life as the two determinants. The conceptual model of the theory of green purchasing behavior is reproduced in Figure 3 [40]. This graphical representation marks the contribution of each theory in the conceptual model. As presented in Figure 3, three additional factors, namely the image of green purchasing, attitude towards green purchasing, and social norm, interact with the personal norm generation process proposed by the norm activation theory. Based on the proposed theory, the image of green purchasing supports both the generation of awareness of the consequences of an action or situation with regard to environmental issues as well as the attitude towards green purchasing behavior. On the other hand, social norm is presented as one of the determinants of personal norm. The integration of these three factors into the values–beliefs–norms theory provides a comprehensive theoretical framework in the formation of green purchasing behavior as presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of the theory of green purchasing behavior.

For the purpose of this study, the theory of green purchasing behavior was tested partially to identify and confirm the determinants of personal norm—namely attitude toward green purchasing, the ascription of responsibility, and social norm—and the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior. As the main contribution of this study, LOHAS orientation was integrated into the model as the mediating factor that is expected to regulate the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior.

2.2. Determinants of Personal Norm and Its Effect on Green Purchasing Behavior

Personal norms are the feelings of a person related to a moral obligation to perform or refrain from an action [46]. Personal norms are formed through the process of comparison between internal values and self-expectations related to a behavioral situation. When a person is involved in a behavioral decision situation, the value system is activated; this person evaluates different courses of action in terms of their implications in the framework of these relevant values, and at the end of this evaluation process, personal norms specific to that situation are formed [47]. In the context of green purchasing behavior, personal norms involve a feeling of moral obligation to engage in pro-environmental behavior, and these norms, if present at the personal level for this specific context, lead to a shift from a general predisposition to a pro-environmental behavior [48,49].

In this study, one of the proposed determinants of personal norm is social norm. Social norm, as a concept utilized in the field of social psychology, can be explained in terms of normative influence on behavior and defined in two different ways, namely descriptive and injunctive norms, referring to two separate types of motivating factors [50]. The descriptive type of norm represents what a normal and typical situation is, such as the things that most people do [51]. This type of behavior provides evidence of taking effective and adaptive action. On the other hand, injunctive norms involve approval motivation and are related to what most other people approve or disapprove of in a specific behavioral situation [52]. In the green purchasing behavior context, social norms are generally associated with the injunctive norms that link the behavior with the social approval related to the pro-environmental behavior. Previous studies in the literature clearly indicate the effects of social norms on personal norm formation. Previous studies confirmed that a contradiction between the social norms and actual behavior of a person leads to a dissonance, which in turn triggers a change in the personal norm, through the feeling of guilt, in the direction of complying with the social norm [53]. Thus, it is expected that a social norm related to a pro-environmental behavior will promote the generation of a personal norm related to the pro-environmental behavior. In light of the theoretical framework and relevant literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

The stronger the social norm related to the pro-environmental behavior, the stronger the personal norm related to the pro-environmental behavior.

Another important proposed determinant of personal norm is the attitude toward green purchasing behavior. An attitude is a type of psychological tendency to generate a positive or negative approach toward an entity through an evaluation process [54]. The construct is regarded as a behavioral disposition acquired through a learning process [54,55]. In the context of green purchasing behavior, an attitude is formed through the awareness of the consequences derived from anthropogenic risks. This, in turn, leads to the evaluation of the situation and triggers the generation of a moral obligation to take a pro-environmental action, which qualifies as a personal norm [40]. Thus, the attitude toward green purchasing behavior is expected to influence the personal norms of consumers. In light of the theoretical framework and relevant literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

The more positive the attitude toward green purchasing behavior, the stronger will be the personal norm related to environmental protection.

The ascription of responsibility, the third proposed determinant of personal norm, involves the person’s own responsibility in reducing the negative environmental impact generated by humans [43]. The values–beliefs–norms theory involves a sequential process starting with the generation of an ecological worldview based on personal values, which leads to the formation of awareness related to the negative consequences of humans activity for the environment, eventually triggering a feeling of personal responsibility [49,56]. Thus, the values–beliefs–norms theory involves an awareness related to the negative consequences of a specific behavior as the source of feeling a responsibility toward a specific subject, which, in turn, leads to the generation of a personal norm related to that subject [47]. Previous studies in the literature provide empirical support for this positive and significant chain effect leading to the formation of the ascription of responsibility, which, in turn, generates a personal norm related to pro-environmental behavior [41,57,58]. Thus, it is expected that the ascription of responsibility related to environmental protection will promote the generation of a personal norm related to pro-environmental behavior. In light of the theoretical framework and relevant literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

The stronger the ascription of responsibility related to environmental protection, the stronger will be the personal norm related to pro-environmental behavior.

Pro-environmental behavior can be explained through the norm activation theory as a function of an awareness of consequences, an acceptance of responsibility, and personal norm [37]. Thus, when there is a high intensity of awareness of consequences and the person feels responsibility for these consequences, personal norms will be generated based on this belief, which eventually leads to behavior aiming to prevent those negative consequences [38]. Previous studies in the literature confirm the positive effect of personal norms on the pro-environmental behavior of consumers. In a meta-analysis including 572 studies, comparing different norm constructs and their effects on pro-environmental behavior, the authors reported that personal norms are the strongest predictor of pro-environmental behavior [59]. Thus, it is strongly believed that stronger personal environmental norms will promote green purchasing behavior. In light of the theoretical framework and relevant literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Higher levels of personal environmental norm will lead to higher levels of green purchasing intentions among consumers.

2.3. LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability)

LOHAS, which stands for Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability, is a concept proposed by Ray and Anderson (1998) [28] and involves a lifestyle that promotes physical and psychological health and care for sustainable environmental development at the perceptual, attitudinal, and behavioral levels [60]. In other words, consumers with a LOHAS orientation aim to improve the quality of value in the domain of health and sustainability by preferring and consuming locally produced eco-friendly products, contributing to the environmental, social, and economic sustainability of their communities [61]. Thus, this segment of consumers may be regarded as green materialists, as they satisfy their desires by purchasing eco-friendly products [29]. The LOHAS segment is demographically characterized as an affluent, morally responsible and well-educated group of consumers having consumption preferences in line with their personal beliefs [62]. The Natural Marketing Institute identified the typical LOHAS consumer as a middle-aged woman who is married, generally has no children, and has a high education level and income [63]. However, it is not possible to identify LOHAS consumers using demographic criteria alone because other factors, such as the value orientations of consumers, are expected to shape their attitudes [64]. The size of this consumer segment grows around 10% each year, and the total number of consumers with a LOHAS orientation is expected to reach 30% of the total US population, pushing related businesses to consider these consumers an important target segment [65]. In line with the growing size of the consumer population, the total addressable market (TAM) as well as the potential economic value generation of the LOHAS segment is expected to reach USD 500 bn [66].

Choi and Feinberg (2024) reviewed the conceptualization of LOHAS in the related literature and provided four areas of focus related to the characteristics of LOHAS, which collectively form the orientation of this consumer segment [29]. LOHAS consumers are regarded as individuals who show deep interest and care in terms of health and well-being for themselves as well as their families by consuming natural and even organic foods [28]. Consumers with a LOHAS orientation can be regarded as the early adopters of eco-friendly products. Thus, these consumers become aware of such products before the rest of the community, adopt them into their lifestyles, and thus impact their close circles, such as families and friends [35]. They also value holistic health and engage in regular physical exercise combined with the utilization of complementary and alternative medicine [67]. Another important characteristic of these consumers is their ecological orientation, by which they show higher sensitivity in terms of protecting the environment and consuming products and services with pro-environmental lifecycles [25]. They pay attention to the environmental standards applied in the production of products and to eco-labels and the information they provide [68]. The most credited value type for consumers with a LOHAS orientation, which is delivered through the consumption of products, is not based on functional or emotional value; instead, the environmental value is the leading type of value [69]. Thus, consumers with a LOHAS orientation show a propensity to pay higher prices for eco-friendly products that match their identities and values [70]. Environmental value is not the only type of leading value; the social value inherent in the lifecycles of products is also an important determinant factor in the consumption preferences of consumers with a LOHAS orientation. These consumers show higher levels of social sustainability sensitivity, which, in turn, affects their consumption preferences in favor of products meeting their social responsibility standards [71]. Another important characteristic of consumers with a LOHAS orientation is their engagement in personal development activities, especially through spiritual practices including mediation, yoga, and other related applications [72]. This type of consumer possesses inherent values that reflect their relationship orientation, their optimistic view of the future, and an openness to new things [73].

Previous studies in the relevant literature confirm that consumers with a LOHAS orientation tend to show a higher propensity to purchase and consume eco-friendly products in several sectors and contexts. In a study, consumers with a LOHAS orientation were identified as a group with a specific buying behavior, and this study reported that a LOHAS orientation positively impacted purchasing behavior. The authors concluded that the characteristics of the LOHAS consumer segment, which are defined as LOHAS factors, significantly influence the structure of buying behavior by generating a preference for the products of companies with similar social values, and support for domestic and local producers [30]. Another study investigated the determinants of green purchasing behavior among Indian consumers in the retail context. The authors reported that the attitude toward green products and environmental concern of consumers had a positive and significant effect on green purchasing behavior [31]. A study conducted in the textile industry investigated the effect of the LOHAS consumption tendency on the purchasing intentions for upcycled fashion goods in South Korea. The author of the study reported that the LOHAS consumption tendency had a significant and positive effect on brand trust, which, in turn, positively influenced the purchasing intention toward such goods [35]. In the hospitality context, several studies have reported that a LOHAS orientation significantly influences consumers’ purchasing intention and behavior. In a study conducted in the food and nutrition context, the authors investigated the relationship between LOHAS and healthy food choices. The authors conducted the study on a restaurant chain that specialized in healthy dishes and reported that a LOHAS orientation had a significant effect on healthy food choices [32]. Other similar studies investigated the influence of environmental concerns, which are inhibited in a typical LOHAS orientation, on consumer patronage intentions toward green restaurants. The results of this study confirmed that such a LOHAS orientation positively affected consumers’ propensity to patronize green restaurants [17,33]. In a study conducted in the Indian lodging industry, Manaktola and Jauhari (2007) investigated the influence of green practices on consumer attitudes and behavior. The authors reported that green practices had positive and significant effects on the patronage intentions of consumers toward hotels [34]. Thus, it is expected that consumers with a LOHAS orientation will show a propensity to prefer hotels with green practices. In light of the theoretical framework and relevant literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5.

Higher levels of LOHAS orientation will lead to a higher level of green purchasing intention among consumers.

As Blamey (1998) suggests, when a person is involved in a behavioral decision situation, the value system is activated; this person evaluates different courses of action in terms of their implications in the framework of their relevant values, and at the end of this evaluation process, personal norms specific to that situation are formed [47]. Previous studies in the context of environmental protection explain personal norms as feelings of a moral obligation to engage in pro-environmental behavior [48,56]. According to these studies, personal norms may lead to a shift from a general predisposition to pro-environmental behavior. An important characteristic of the LOHAS consumer segment is their ecological orientation, by which they show higher sensitivity in terms of protecting the environment [25]. Thus, it is strongly believed that the behavioral orientation generated by personal environmental norms leads to the generation of stronger LOHAS orientations among consumers. Consumers with a LOHAS orientation exhibit strong social consciousness and can be regarded as the agents of a movement that may lead to cultural change. These consumers are classified into two groups, leaders and followers, where leaders are regarded as more aggressive than followers [70]. This leads us to conclude that consumers with a LOHAS orientation may have differing levels of pro-environmental behavioral intensity, which, in turn, is expected to mediate the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior. In light of the theoretical framework and relevant literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

H6.

Higher levels of personal environmental norm will lead to a higher level of LOHAS orientation among consumers.

H7.

The level of the LOHAS orientation of consumers will have a mediation effect on the effect of personal environmental norm on green purchasing behavior.

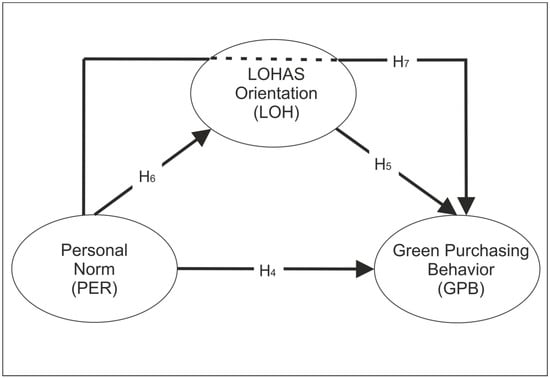

A conceptual model of the study including the proposed hypotheses is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Conceptual model of the study and proposed hypotheses.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

Based on the theory of green purchasing behavior, this study aimed to identify the determinants of personal norm in the context of hospitality and extended the model by measuring the effect of a LOHAS orientation on the effect of personal norm in green purchasing behavior. The study is designed as a quantitative field study conducted through the administration of a survey. The questionnaire employed in the survey was prepared by employing the validated scales of the constructs borrowed from the relevant literature, and before finalizing the questionnaire, its face validity was checked with five academics and five consumers. Following the face validity checks, some scale items in the questionnaire were rephrased to prevent nonresponse problems. The questionnaire was distributed to the participants through the Survey Monkey electronic survey system. The participants were selected from white-collar professionals working in several companies from different industries in the three largest cities of Turkey, namely Istanbul, Ankara, and İzmir, who regularly purchased summer holidays and visited hotels during their summer vacations. This research received no external funding. Before conducting the field study, approval was obtained from the Istanbul Okan University ethics committee, with protocol number 179, on 5 June 2024. A convenience sampling methodology using the close circles and professional networks of the researchers was employed to identify participants for the study. This sampling methodology limits the generalizability of the results because it included a specific type of consumer profile composed of white-collar professionals. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study. A total of 418 valid questionnaires out of 459 distributed questionnaires were collected, and those valid questionnaires were included in the analysis. The demographic distribution of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of participants.

In the next stage of the study, confirmatory factor analysis was employed to confirm the convergent validity of the constructs. To determine the discriminant validity, the square roots of the AVE values of the variables were calculated [74]. To confirm the reliability of the scales, the composite reliability and Cronbach α values were calculated. Structural equation modeling (SEM) using the IBM SPSS V28 and IBM SPSS AMOS V28 software was employed to test the hypotheses of the main model. Because the main model consists of multiple regressions including exogenous and endogenous variables, the structural equation modeling method was selected, which is suitable for testing such a model. This method allows all regressions to be tested simultaneously and minimizes measurement errors [74]. To test the hypotheses of the post hoc model, Baron and Kenny’s method was employed and implemented by testing three regression models [75].

3.2. Operationalization of Variables

The scales of the variables in the research model were adopted from the existing studies in the related literature. The scales of the variables proposed as determinants of personal norm—the attitude toward green purchasing, the ascription of responsibility, and social norm—as well as the scales of other variables in the model, including personal norm and green purchasing behavior, were taken from relevant studies in the literature [24]. A five-item scale for the attitude toward green purchasing was adopted by the author based on several studies in the literature, and the validity and reliability of the five-item scale was confirmed by the author. Similarly, three-item scales for the ascription of responsibility, social norm, personal norm, and green purchasing behavior were adopted based on the relevant literature. The validity and reliability of all of these scales were confirmed. The items of these scales are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main model variables and scale items.

The LOHAS orientation scale was adopted from the study of Choi and Feinberg (2021). The authors developed and validated a twenty-eight-item LOHAS orientation scale composed of six components including physical fitness, mental health, emotional health, spiritual health, environmentalism, and social consciousness [76]. The items of the LOHAS orientation scale are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

LOHAS orientation scale items.

3.3. Validity and Reliability Checks

In this study, the validated scales of the constructs were taken from the extant literature, and before finalizing the questionnaire, its face validity was checked with five academics and five consumers. Following the face validity checks, some scale items in the questionnaire were rephrased to prevent nonresponse problems. It was deemed that, in addition to these procedures, the validity and reliability of the scale should be confirmed again based on the collected data. Therefore, the validity and reliability of the scales in both the main model and the post hoc model were evaluated.

3.3.1. Validity and Reliability of Main Constructs

Before confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to purify the data. After this operation, two components were eliminated, and 16 components remained. CFA is used to determine whether an adapted scale has convergent validity [74]. The CFA’s fit index values were considered adequate (i.e., χ2/DF = 2.323, CFI = 0.982, IFI = 0.982, and RMSEA = 0.056). The loads of the factors in the CFA are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis results for the main constructs.

Table 5 presents the average extracted variance (AVE) values. These values were higher than the threshold level (i.e., 0.5) [74]. The CFA and AVE scores demonstrated that the components of the scales had convergent validity [77]. Additionally, it was deemed that the discriminant validity of the scales should be evaluated. For this, the square roots of the AVE values of the variables were calculated [74]. The values in brackets in Table 5 are the square roots of the AVEs. The correlation values in the same column are smaller than the square roots of the AVEs, again showing discriminant validity. Subsequently, the reliability of the structures was evaluated; the reliability scores were higher than the suggested level of 0.7 [78].

Table 5.

AVE, reliability, and correlation values of the constructs.

The coefficients of the correlations between dimensions, the Cronbach α scores, the composite reliabilities, and the AVE values are shown in Table 5.

3.3.2. Validity and Reliability of LOHAS Orientation Scale

Before confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to purify the data. As a result of this analysis, eight components were eliminated, and 21 components remained. CFA is used to determine whether an adapted scale has convergent validity [74]. The loads of the factors in the CFA are shown in Table 6. The CFA’s fit index values were considered adequate (i.e., χ2/DF = 2.385, CFI = 0.955, IFI = 0.955, and RMSEA = 0.058).

Table 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis results for the LOHAS orientation scale.

Table 7 presents the average extracted variance (AVE) values. These values were greater than the threshold level (i.e., 0.5) [74]. The CFA and AVE findings demonstrate that the components of the scales have convergent validity. The discriminant validity of the scales was also evaluated. The square roots of the AVE values of the variables were calculated to determine the discriminant validity [74]. The values in brackets in Table 7 are the AVE values’ square roots. The correlation values in the same column are all less than the square roots of the AVE values. This indicates that the discriminant validity is also provided. Subsequently, the reliability of the structures was evaluated. The reliability scores were higher than the suggested level of 0.7 [78].

Table 7.

AVE, reliability and correlation values of the constructs.

The coefficients of the correlations between dimensions, the Cronbach α scores, the composite reliabilities, and the AVE values are shown in Table 7.

4. Tests of the Hypotheses

The hypotheses were tested in two stages. First, the main model consisting of basic structures was tested. Subsequently, the post hoc model that was developed to understand the role of the LOHAS orientation in the relationship between personal norm and green purchasing behavior was tested.

4.1. Test of Main Model

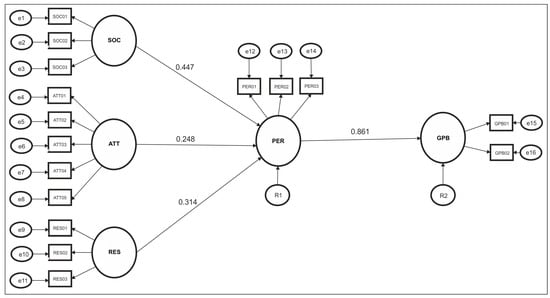

The goodness of fit indices were evaluated to determine how well the model was fit. The main model’s fit indices were considered adequate (χ2/DF = 2.586, CFI = 0.978, IFI = 0.978, and RMSEA = 0.062). The graphical presentation of the SEM analysis of the main model is provided in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

SEM analysis of the main model. Note: χ2/DF = 2.586, CFI = 0.978, IFI = 0.978, and RMSEA = 0.062.

The results of the hypothesis testing confirmed that H1, H2, H3, and H4 were all accepted, implying that SOC, ATT, and RES each have a significant direct effect on PER and PER has a significant direct effect on GPB. The results of the hypothesis testing are provided in Table 8.

Table 8.

Hypothesis test results.

4.2. Test of Post Hoc Model

To test the hypotheses of the post hoc model, Baron and Kenny’s method was employed. This model confirms a mediation effect when the mediator and independent variables are included in the regression equation (Model 3) and the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is reduced or eliminated [75]. The post hoc model is displayed in Figure 6. Three regression models among personal norm (PER), LOHAS orientation (LOH), and green purchasing behavior (GPB) are provided below:

Figure 6.

Post hoc model.

- Model 1: GBP = β0 + β1.PER + ε (H4);

- Model 2: LOH = β0 + β1.PER + ε (H6);

- Model 3: GBP = β0 + β1.PER+ β2.LOH + ε (H5 and H7).

In the first step, the Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated because Baron and Kenny’s method requires a significant relationship among the three variables [74]. As shown in Table 9, the Pearson correlation coefficients were indeed statistically significant. The R and R2 values of the three models are presented in Table 10. In Table 11, the ANOVA results indicate that the models were statistically significant. The hypothesis test results are provided in Table 12.

Table 9.

Correlation coefficients.

Table 10.

Model summaries.

Table 11.

ANOVA table.

Table 12.

Hypothesis results.

As indicated in Table 12, the results demonstrate a positive and significant relationship between PER and LOH (βmodel2 = 0.506, p < 0.01). Thus, H6 (personal norm has a positive effect on LOHAS orientation) was supported. H5 (LOHAS orientation has a positive effect on green purchasing behavior) was also supported (βmodel3 = 0.193, p < 0.01). H4 (personal norm has a positive effect on green purchasing behavior) was supported (βmodel1 = 0.751, p < 0.01), while H7 (LOHAS orientation has a mediator role in the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior) was not supported (βmodel3 = 0.654, p > 0.01). This is because the effect of PER on GBP does not disappear or decrease significantly after the inclusion of the mediator variable in the model. It was therefore concluded that LOH does not play a mediator role between PER and GPB.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to incorporate the LOHAS orientation of consumers in the conceptual models of the norm activation theory [37], the values–beliefs–norms theory [41], and the theory of green purchasing behavior [24]. Specifically, based on the three theoretical frameworks and the incorporation of LOHAS orientation in these frameworks, the determinants of personal norm were identified, the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior was tested, and, finally, the mediating effect of LOHAS on the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior was tested.

Based on the theoretical models employed and findings in the literature, social norm was identified as one of the determinants of personal norm. In order to answer the research question “Does the social norm in the context of environmental issues contribute to the formation of personal norm in the same context?”, the associated hypothesis was tested. This confirmed that social norm had a positive effect on personal norm regarding environmental issues. As suggested in existing studies, social norms and especially injunctive norms are highly effective in the formation of personal norm [51]. Previous findings in the literature confirm the regulatory effect of social norm on personal norm in the case of a contradiction between the social norm and the actual behavior of a person [53]. In a study investigating the role of injunctive social norms and personal norms on pro-environmental behavior in the tourism context, the authors reported that social norms had a significant effect on the formation of personal norms [79]. Another study investigated the roles of social norms, personal costs and personal norms in the formation of pro-environmental behavior in the green product context; the authors reported that personal norms had a significant mediating effect on the effect of social norms on pro-environmental behavior [80]. In a similar study, which meta-analyzed the predictive power of social and personal norms regarding pro-environmental behavior, personal norms were found to have a mediating role in the effect of both injunctive and descriptive norms on pro-environmental behavior [59]. Kim and Seock (2019) investigated the effects of social norm on personal norm in the USA apparel product category. The authors confirmed that social norms had a strong effect on the personal norm of consumers that ultimately led to purchasing behavior [81]. Another study investigated the effects of injunctive social norms on both personal norms and behavioral intentions, and the authors confirmed that injunctive social norms had a strong effect on personal norms [82]. Bertoldo and Castro (2016) investigated the effect of social norms on personal norms in the context of recycling and organic food product purchases in Portugal and Brazil. The authors reported a significant effect of social norms on personal norms, where injunctive norms were found to better predict personal norms when the participants were more identified with the group compared to descriptive norms, which had a more direct effect on personal norms [83]. The finding of this study regarding the positive effect of social norm on personal norm is conclusive because this result is supported by both the theoretical frameworks and the findings of previous studies.

The second important determinant of personal norm was identified as the attitude toward green purchasing behavior. In order to answer the research question “Does the attitude toward green purchasing lead to the formation of personal norm in the context of environmental issues?”, the associated hypothesis was tested. This confirmed that the attitude toward green purchasing behavior had a positive effect on the personal norm regarding environmental issues. An attitude is formed through a learning process [54]; the attitude toward green purchasing behavior is formed through an awareness of the consequences derived from the anthropogenic risk related to the environment. This situation leads to an evaluation of the current situation and triggers the generation of a moral obligation related to environmental protection [40]; eventually, this moral obligation translates into a personal norm for the consumer. Previous studies provide strong evidence for a significant effect of pro-environmental attitudes on the formation of personal norms. In a study conducted in the green hotel context, the determinants of consumer green purchasing behavior were identified by employing a values–beliefs–norm framework. One of the findings of their study was that implicit attitudes had a significant effect on the formation of personal norm [84]. Other studies have also confirmed the effect of the attitude toward green purchasing behavior on personal norm [24]. In light of these findings and theoretical support, it can be concluded that the finding of this study regarding the positive effect of attitude toward green purchasing behavior on personal norm is conclusive, because this result is supported both by the theoretical frameworks and by the findings of the previous studies.

The third important determinant of personal norm was identified as the ascription of responsibility. In order to answer the research question “Does the ascription of responsibility in the context of environmental issues lead to the formation of personal norm in the same context?”, the associated hypothesis was tested. This confirmed that the ascription of responsibility had a positive effect on the personal norm regarding environmental issues. The generation of personal norm through the ascription of responsibility is proposed by both the norm activation theory and the values–beliefs–norms theory. Based on these theories, awareness related to the consequences of an action leads to the ascription of responsibility related to that subject, and this in turn translates into a personal norm. Previous studies also confirmed the significant effect of the ascription of responsibility on the formation of personal norm. In a study investigating the role of injunctive social norms and personal norms in determining pro-environmental behavior in the tourism context, one of the findings was that the ascription of responsibility had a significant effect on the formation of personal norms [79]. In another study, which investigated the role of personal norms and situational expectancies in the generation of sustainable behavior, the results confirmed that the ascription of responsibility had a significant effect on the formation of personal norms [85]. Setiawan and colleagues (2021) investigated the effect of the ascription of responsibility on the formation of personal norm in the consumer household waste management context. The authors reported a significant effect of the ascription of responsibility on the formation of personal norm [86]. In a similar study aiming to predict self-reported water reduction behavior in the USA, the results confirmed the ascription of responsibility and its interaction with personal norms as important predictors of self-reported behavior [87]. The finding of this study regarding the significant effect of the ascription of responsibility on personal norm is conclusive because it is supported by both the theoretical frameworks and the findings of the previous studies.

This study aimed to contribute to the existing literature by incorporating LOHAS as the mediating variable into a green purchasing behavior theoretical model. In order to answer the research question “Does the existence of personal norm in the context of environmental issues lead to green purchasing behavior?”, the associated hypothesis was tested. This confirmed that personal norms have a positive and significant effect on green purchasing behavior. In addition to the theoretical support provided by the values–beliefs–norms theory as well as the theory of green purchasing behavior, several previous studies also confirmed personal norms as one of the strongest predictors of green purchasing behavior. In a meta-analysis of the predictive power of social and personal norms for pro-environmental behavior, personal norms were reported as one of the predictors [59]. Another study investigated the effects of social and personal norms as normative influences on pro-environmental behavior in the context of parks and protected areas; the authors reported that personal norms had a significant effect on pro-environmental behavior [88]. Thus, in light of the theoretical and strong empirical support, the finding of this study regarding the significant effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior is conclusive. In order to answer the research question “Does the existence of personal norm in the context of environmental issues lead to the formation of a LOHAS orientation?”, the associated hypothesis was tested. This confirmed that personal norm had a significant effect on the LOHAS orientation of consumers. As the personal pro-environmental norms are regarded as feelings of moral obligation regarding environmental issues and a LOHAS orientation reflects a high level of environmental sensitivity [25,48,56], the finding of this study makes sense both theoretically and empirically. In a study investigating the determinants of active transport behavior by employing the value–attitude–behavior framework, the authors identified personal norms as a determinant [89]. The results of their study show a link between the healthy living components of personal norm that are also inherent in the LOHAS orientation and the active transport behavior of consumers. In order to answer the research question “Does the LOHAS orientation of consumers lead to involvement in green purchasing behavior?”, the associated hypothesis was tested. The LOHAS orientation of consumers was found to have a statistically significant effect on green purchasing behavior. This result is supported by the findings of many studies in the literature conducted in several different contexts. In a study investigating the effects of individualist and collectivist motives on the behavioral outcomes of LOHAS orientation, the authors reported that LOHAS orientation had a significant effect on status consumption, which involves purchasing natural and organic brands, in the context of green purchasing behavior [29]. In a study investigating the determinants of green purchasing behavior among Indian consumers in the retail context, the authors reported that environmental concern had a significant and positive effect on green purchasing behavior [31]. In the food and nutrition context, a study investigated the effect of LOHAS orientation on healthy food choices and confirmed that LOHAS orientation had a significant and positive effect on healthy food consumption [32]. Similarly, a study investigated the influence of environmental concerns, which are inhibited in a typical LOHAS orientation, on consumer patronage intentions toward green restaurants and reported a significant and positive effect [17,33]. Another study conducted in the Indian lodging industry investigated the influence of green practices on consumer attitudes and behavior and reported a positive and significant effect of LOHAS orientation on consumer patronage intentions [34]. In light of the theoretical as well as empirical support, the finding of this study regarding the significant effect of LOHAS orientation on the intention to become involved in green purchasing behavior is conclusive.

In order to answer the research question “Does the LOHAS orientation of consumers mediate the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior?”, the mediation effect of LOHAS orientation on the effect of personal norms on green purchasing behavior was analyzed. This yielded a statistically insignificant result, which leads us to elaborate the result from a construct-based perspective. In order to accept a mediation effect, the inclusion of the mediator variable should eliminate or significantly reduce the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. In this study, the inclusion of LOHAS in the model did not significantly reduce the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior. This can be explained by comparing the structure of personal norm and LOHAS orientation from a construct-based perspective. The core of a personal norm is the feeling of a person related to a moral obligation to engage or not engage in an action in a specific context [46], guided by internal values, which eventually leads to the formation of personal norms [47]. A personal norm in the context of the environment is the feeling of a moral obligation to engage in pro-environmental behavior [48]. LOHAS, on the other hand, involves a lifestyle that promotes physical and psychological health and care for sustainable environmental development at the perceptual, attitudinal, and behavioral levels [60], and it is a reflection of personal norm in these areas of concern. Thus, personal norm determines the strength of the LOHAS orientation of consumers, as confirmed by the results of the hypothesis testing in this study. From this perspective, it can be concluded that the insignificant result regarding the mediation effect of LOHAS orientation may be explained in terms of the regulatory power of personal norm over the LOHAS orientation of consumers, and it is more powerful in its effect on green purchasing behavior than the effect of LOHAS orientation on green purchasing behavior. Thus, the inclusion of LOHAS orientation in the model as the mediating factor did not totally eliminate or significantly reduce the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior.

The findings of this study provide several insights for marketing and brand professionals in the field. First of all, the dominance of personal norms over the LOHAS orientation of consumers in terms of its effect on green purchasing behavior necessitates a shift in the focus of marketing communications strategy from a micro (lifestyle) perspective to a more holistic and macro (environmental and social) perspective. While the former is more focused on the generation of personal value in the value mix, the latter involves the generation of environmental and social value in the same value mix. Thus, although the value propositions of brands would be the same, the channels, programs, message, and content strategy of the same brands need to be adapted to the dynamics and interactions between personal norms, LOHAS orientation, and green purchasing behavior. In other words, marketing communications channels, programs, messages, and content strategy need to be structured in a way that will convince consumers to become involved in green purchasing behavior through the generation and empowering of pro-environmental personal norms rather than through the synchronization of brand-consumer lifestyles.

Brands need to employ the correct marketing communication channels in their mix to generate the desired effects on their target consumer segment. The primary target should be the employment of channels and tools that will enable the generation of collective wisdom and co-intelligence elements regarding environmental risks as well as the responsibility to develop a strong pro-environmental personal norm. The second important aim of such marketing communication activities and programs is to direct the behavioral outcome of such a pro-environmental personal norm toward the brand through the empowerment of brand image. From this perspective and in line with the abovementioned targets, sponsorships of events, organizing events, and cause-related marketing programs that aim to connect the brand’s purpose with environmental causes will be important and powerful tools for promoting a pro-environmental image of the company. Moreover, such activities and programs will also help to generate collective wisdom and co-intelligence elements that feed the pro-environmental personal norm. In sponsorship projects, the target is the transfer of image elements from the event to the sponsor in order to support a pro-environmental image. From this perspective, sponsorships of events focusing on the generation of awareness related to environmental risks or the targeted funding of environmental projects will be important tools for realizing such positioning targets as well as generating collective wisdom and co-intelligence elements for the target consumer segment of the company, supporting the generation of a personal norm related to pro-environmental behavior. Marketing communication activities and programs, which involve direct contributions from brands, such as the organization of events or the development of cause-related marketing programs with the purpose of generating pro-environmental awareness as well as funding for environmental projects, will also empower the pro-environmental personal norm of the target consumer segment of the company. Any pro-environmental marketing communication activity and marketing program performed by the company will eventually support the generation of a pro-environmental personal norm among the target consumer segment, which, in turn, is expected to become involved in green purchasing behavior. In order to successfully generate or empower pro-environmental personal norms, marketing communications messages and content strategies also need to include collective wisdom or co-intelligence elements, which, ultimately, will convince customers that the correct code of conduct regarding environmental issues is to behave responsibly. Thus, in any type of marketing communication activity or marketing program, the content strategy, which includes what to articulate and how, should include elements of generating awareness of environmental risks and persuading target consumers to behave responsibly in order to feed the personal norm in the intended direction. A second important factor in the generation or empowering of pro-environmental personal norms is the articulation or demonstration of the consequences of not being compliant with the collective wisdom presented in messages. These two content elements need to be used in conjunction and in tandem so that they support each other and generate an overall effect on the formation of targeted personal norms.

6. Conclusions

The objective of this study was to identify the determinants of personal norm and to measure the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior as well as to measure a possible mediating role of consumer LOHAS orientation in the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior in the hospitality context. The findings of this study provide considerable contributions to the academic literature and provide valuable insights for practical applications. The results confirm that social norms, the ascription of responsibility related to environmental issues, and the attitude toward green purchasing behavior were determinants of personal norm related to pro-environmental behavior. In turn, personal norm is found to be affective on green purchasing behavior. These results were supportive and conclusive with respect to the theoretical framework, namely the norm activation theory and values–beliefs–norms theory, presented in the study. Thus, the study makes a contribution to the academic literature by confirming the proposed chain of effects regarding the generation of green purchasing behavior. On the other hand, personal norm is found to be effective in the formation of LOHAS orientation and triggering green purchasing behavior. This result is one of the most important contributions of the study to the academic literature in that it is a novel finding and sheds light on an unexplored area of investigation in the LOHAS literature, leading to the generation of a knowledge base. Another important finding of this study was that the LOHAS orientation of consumers did not play a mediating role in the effect of personal norm on green purchasing behavior. This finding is also an important contribution of this study to the academic literature, as it provides valuable insights into practical applications, and it sheds light on another unexplored area of investigation in the LOHAS literature by confirming the regulatory power of personal norm over the LOHAS orientation of consumers, contributing to the foundation of a knowledge base in the relevant literature. In terms of practical implications, this result confirms personal norm as one of the determinants of the LOHAS orientation level. From this perspective, it is an important and valuable insight for brand and marketing managers because it provides a guide and direction for generating effective marketing communication strategies, selecting marketing communication channels and generating a content strategy to influence the personal norm, which is the determinant of the LOHAS orientation level as well as one of the determinants of green purchasing behavior.

Although the findings of this study are valuable and contribute to the existing literature, some limitations of this study need to be mentioned. First, because the study was conducted in the context of green hotel holiday purchases, the generalizability of the results for the hospitality sector is limited. The testing of the hypothesis in different hospitality contexts may generate contradictory results compared to the findings of this study. A second and important limitation is the sampling methodology. Convenience sampling was employed in this study, and the sample was composed of close circles and professional networks of the researchers. This sampling methodology also limits the generalizability of the results because it included a specific type of consumer profile composed of white-collar professionals. A third important limitation of the study in terms of its generalizability is the cultural context in which the study was conducted. Cultural differences among consumer groups may result in different attitudinal as well as behavioral outcomes regarding green purchasing behavior. Previous research focus on the effect of cultural orientation on the environmental approach confirmed that the national identity of Turkish consumers includes several pro-environmental personal norm attributes, which eventually leads to the formation of cultural value for environmental responsibility [90]. From this perspective, the study has some limitations in terms of the generalizability of the results based on the cultural context.

In the light of the limitations of this study, several recommendations for further studies need to be articulated. First, as the study was conducted to measure the behavioral outcome regarding green hotel purchasing, studies in other hospitality areas such as the food and beverage, travel and transportation, and event and entertainment sectors should be conducted. This will help in testing and confirming the findings of this study in different hospitality contexts and will contribute to the knowledge base. Further studies may be also conducted in different cultural contexts because the participants of this study were of a specific cultural profile; different cultural orientations may lead to different behavioral effects of LOHAS orientation. Moreover, the same study may also be expanded to other sectors to understand the effects of LOHAS orientation in other industrial contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.S.; methodology, M.E.C.; validation, A.V.E.; formal analysis, M.E.C.; investigation, A.V.E.; resources, E.G.S.; data curation, M.Ç.P.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.S.; writing—review and editing, A.V.E.; visualization, M.Ç.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study is approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Okan University, Istanbul, Turkey with protocol number 179 on 5 June 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13979696, reference number 13979696.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Overshoot Day. Available online: https://overshoot.footprintnetwork.org/about-earth-overshoot-day/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- WWF (World Wildlife Fund). Living Planet Report: Biodiversity, Bio Capacity and Development; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WWF (World Wildlife Fund). Living Planet Report: Building a Nature—Positive Society; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wijekoon, R.; Sabri, M.F. Determinants That Influence Green Product Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behavior and future research directions. Int. Str. Man. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chen, C.; Lho, L.H.; Kim, H.; Yu, J. Green Hotels: Exploring the Drivers of Customer Approach Behaviors for Green Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.F. A research on environmental issues applied to the hotel industry. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 430–432, 1159–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, S.I.; Arafat, H.A. Reduction of food waste generation in the hospitality industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhajan, C.; Neetoo, H.; Hardowar, S.; Boodia, N.; Driver, M.F.; Chooneea, M.; Ramasawmy, B.; Goburdhun, D.; Ruggoo, A. Food waste generated by the Mauritian hotel industry. Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2022, 3, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostivint, C.; Östergren, K.; Quested, T.; Soethoudt, J.M.; Stenmarck, A.; Svanes, E.; O’Connor, C. Fusions—Food Waste Quantification Manual to Monitor Food Waste Amounts and Progression; European Commission (FP7), CSA: Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Sustainable Carbon Credits Strategy for the Hospitality Industry. 2024. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/uk/en/Industries/consumer/blogs/sustainable-carbon-credits-strategy-for-the-hospitality-industry.html (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Sustainable Hospitality Alliance. Global Hotel Decarbonisation Report. 2017. Available online: https://sustainablehospitalityalliance.org/resource/global-hotel-decarbonisation-report/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Sustainable Hospitality Alliance. Water Stewardship for Hotel Companies Report. 2018. Available online: https://sustainablehospitalityalliance.org/resource/water-stewardship-for-hotel-companies/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Tzschentke, N.A.; Kirk, D.; Lynch, P.A. Reasons for going green in serviced accommodation establishments. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Man 2004, 16, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.H.; Parsa, H.G.; Self, J. The dynamics of green restaurant patronage. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Hawkins, R. Attitude towards EMSs in an international hotel: An exploratory case study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, E.; McLaren, A.; Li, L. Environmentally related research in scholarly hospitality journals: Current status and future opportunities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D.; Svaren, S. How ‘green’ are North American hotels? An exploration of low-cost adoption practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Cvelbar, L.K.; Crün, B. Do pro-environmental appeals trigger pro-environmental behavior in hotel guests. J. Tra. Res. 2017, 56, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I. Environmental Management Practices in US Hotels. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5663351/ENVIRONMENTAL_MANAGEMENT_PRACTICES_IN_US_HOTELS2 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Butler, J. The compelling “hard case” for “green hotel” development. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2008, 49, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, N.C.; Chen, Y.J. On the everyday life information behavior of LOHAS consumers: A perspective of lifestyle. J. Educ. Media Libr. Sci. 2011, 48, 489–510. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfer, J. Lohas and the indigo dollar: Growing the spiritual economy. New Propos. J. Marx. Inq. 2010, 4, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Osti, L.; Goffi, G. Lifestyle of health & sustainability: The hospitality sector’s response to a new market segment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, P.; Anderson, S. The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World; Harmony Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Feinberg, R. Investigating the role of individualism/collectivism as underlying motives and status consumption as a behavioral outcome of LOHAS: Focusing on the moderating effect of materialism. Innov. Mark. 2024, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pícha, K.; Navrátil, J. The factors of Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability influencing pro-environmental buying behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, J.M. Relationship between lifestyle of health and sustainability and healthy food choices for seniors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 558–576. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.C.; Khan, N.; Lau, T.C. Investigating the determinants of green restaurant patronage intention. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behavior towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.H. The influence of LOHAS consumption tendency and perceived consumer effectiveness on trust and purchase intention regarding upcycling fashion goods. Int. J. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 16, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Awareness of consequences and the influence of moral norms on interpersonal behavior. Sociometry 1968, 31, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R.F.; Pranedas, L.; Parada, V.A. Cross-Cultural Assessment of Three Theories of Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Comparison Between Business Students of Chile and the United States. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 634–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T.A. The land ethic realized: Some social psychological explanations for changing environmental attitudes. J. Soc. Issues 1972, 28, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. The new ecological paradigm in social psychological perspective. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behavior—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, R. Turning green subsidies into sustainability: How green process innovation improves firms’ green image. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 1416–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. A Normative Decision-Making Model of Altruism. In Altruism and Helping Behavior: Social, Personality, and Developmental Perspectives; Rushton, P.J., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1981; pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey, R. Contingent valuation and the activation of environmental norms. Eco. Econ. 1998, 24, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ture, R.S.; Ganesh, M. Understanding pro-environmental behaviours at workplace: Proposal of a model. Asia-Pac. J. Manage. Res. Innov. 2014, 10, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A study of normative and informational social influence upon individual judgment. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: A Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human Behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T. Social Attitudes and Other Acquired Behavioral Dispositions. In Psychology: A Study of a Science. Study II. Empirical Substructure and Relations with Other Sciences. Investigations of Man as Socius: Their Place in Psychology and the Social Sciences; Koch, S., Ed.; McGraw—Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963; Volume 6, pp. 94–172. [Google Scholar]