Impeding Digital Transformation by Establishing a Continuous Process of Competence Reconfiguration: Developing a New Construct and Measurements for Sustained Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Analysis

2.1. Learning Goal Orientation

2.2. Growth Mindset

2.3. Organisational Learning

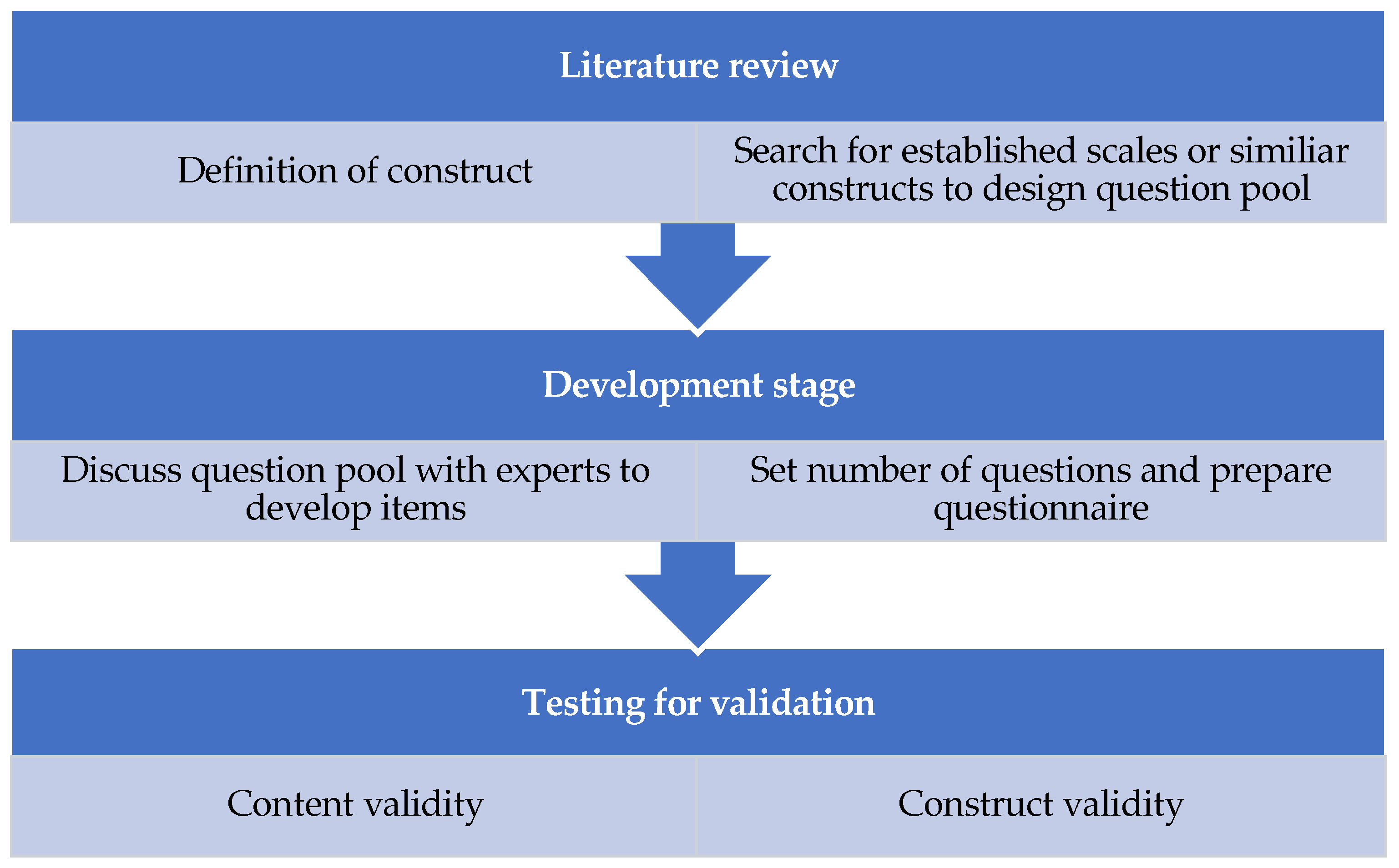

3. Materials and Methods

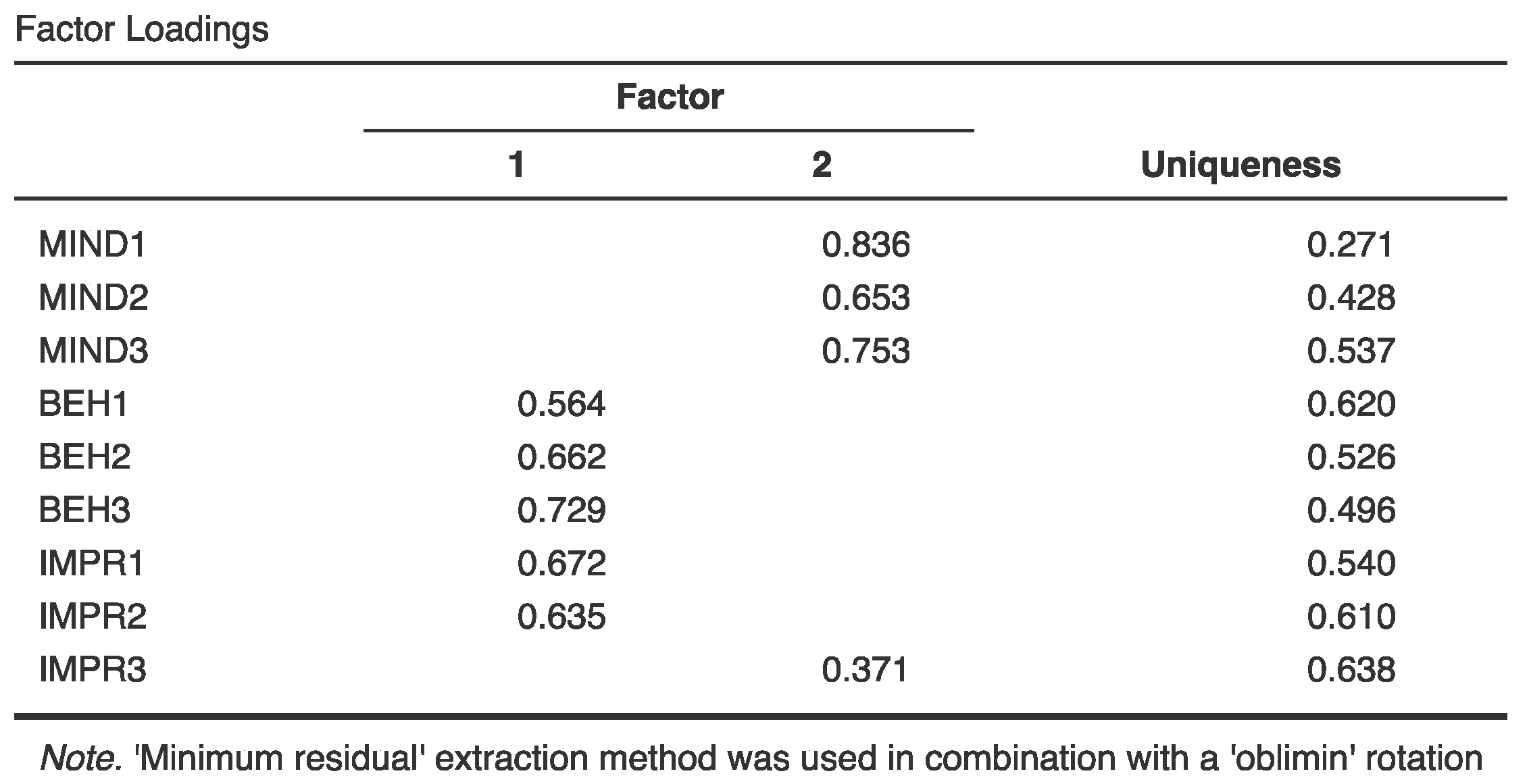

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Open mindset to explore new things.

- Question habits and routines.

- Continuous improvement of own competences.

| Item | Question | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Mindset | I would never stop learning as there is a risk of not keeping up to date and missing out on opportunities. | [62] |

| Mindset | New experiences with digital technologies or tools are learning opportunities for me. | [63] |

| Mindset | I regularly join or listen to conversations and discussions about new technologies. | [64] |

| Mindset | I can derive new ideas from things I have learned. | [65] |

| Mindset | If there are new technologies or tools, which make things easier for me, I want to know more about it. | New |

| Mindset | I incorporate feedback to make changes in my behaviour | [66] |

| Behaviour | I am interested in new topics, try to interact, and informed myself about occurring new technologies. | [65,67,68] |

| Behaviour | I value original ideas and constant innovation. | [69] |

| Behaviour | I am watching explanation videos (e.g., on YouTube or other platforms) and/or read additional instructions to improve my knowledge. | [67] |

| Behaviour | I am not afraid to critically reflect my underlying assumptions. | [64,69] |

| Behaviour | If I learn something new about digital technologies, I think about how I could transfer this into my daily routines. | [67] |

| Behaviour | If I learn something new about digital technologies, I rethink how I did things before and try to make it better based on my new knowledge. | [67] |

| Behaviour | I continuously judge my decisions and activities towards using digital technologies. | [64] |

| Behaviour | One of my basic values is to include learning as a key to improvement. | [69] |

| Improvement | I try to integrate digital technologies, even if I need to think about doing things in a different way I did before. | [63,67] |

| Improvement | I view the ability to learn as the key to improvement. | [62] |

| Improvement | I long for learning to improve myself. | [62] |

| Improvement | I perceive learning as an investment, not an expense. | [62] |

| Improvement | I can transfer the knowledge I already have to adapt other similar technology | [68] |

Appendix B

- Individual attitude: Open mindset to explore new things—Accept.

- Behavioural pattern: Questioning habits and routines—Act and Reflect.

- Outcome: Continuous improvement of competences—Implementation and Learning Loops.

| Item | Question |

|---|---|

| Mindset | If there are conversations and discussions about new technologies in my environment, I am interested in them. |

| Mindset | If someone tells me about new ideas to use technology, I am open to them |

| Mindset | If there are new technologies or tools that make my work easier, I want to know more about it. |

| Behaviour | I watch explanation videos (e.g., on YouTube or other platforms) and/or read additional instructions to improve my knowledge. |

| Behaviour | When I learn something new about digital technologies, I rethink my previous actions and try to develop them further with the new knowledge. |

| Behaviour | If situations are changing, I adapt my decisions and activities regarding the use of digital technologies. |

| Improvement | I acquire new knowledge and skills independently. |

| Improvement | I am willing to invest time and money to integrate new technologies or processes in my daily live. |

| Improvement | The knowledge I already have helps me to use other technologies |

References

- Kraus, S.; Schiavone, F.; Pluzhnikova, A.; Invernizzi, A.C. Digital Transformation in Healthcare: Analysing the Current State-of-Research. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenza, E.; Quintano, M.; Schiavone, F.; Vrontis, D. The Effect of Digital Technologies Adoption in Healthcare Industry: A Case Based Analysis. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.L.; Fogliatto, F.S.; Mac Cawley Vergara, A.; Vassolo, R.; Sawhney, R. Healthcare 4.0: Trends, Challenges and Research Directions. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K. Barriers to Sustainable Digital Transformation in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, S. Der Digitale Wandel Im Gesundheitswesen. HMD Prax. Der Wirtsch. 2022, 59, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.L.; Peter, Z.; Rutter, K.-A.; Somauroo, A. Promoting an Overdue Digital Transformation in Healthcare. Ariel. 2019. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Healthcare%20Systems%20and%20Services/Our%20Insights/Promoting%20an%20overdue%20digital%20transformation%20in%20healthcare/Promoting-an-overdue-digital-transformation-in-healthcare.ashx (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Iyanna, S.; Kaur, P.; Ractham, P.; Talwar, S.; Najmul Islam, A.K.M. Digital Transformation of Healthcare Sector. What Is Impeding Adoption and Continued Usage of Technology-Driven Innovations by End-Users? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaldi, S.; Scaratti, G.; Fregnan, E. Dwelling within the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Organizational Learning for New Competences, Processes and Work Cultures. J. Workplace Learn. 2022, 34, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhem, S.; Jacobsen, A.H. A Global Study on Digital Capabilities; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L.; Fernández-Rodríguez, V.; Ariza-Montes, A. Assessing the Origins, Evolution and Prospects of the Literature on Dynamic Capabilities: A Bibliometric Analysis. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 24, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Prieto, I.M. Dynamic Capabilities and Knowledge Management: An Integrative Role for Learning? Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Araque, B.; Moreno-Garcia, J.; Hernández-Perlines, F. Editorial: Training, Performance, and Dynamic Capabilities: New Insights from Absorptive, Innovative, Adaptative, and Learning Capacities. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1176275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augier, M.; Teece, D.J. Understanding Complex Organization: The Role of Know-How, Internal Structure, and Human Behavior in the Evolution of Capabilities. Ind. Corp. Change 2006, 15, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mahoney, J.T. The Management of Resources and the Resource of Management. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 33, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate Learning and the Evolution of Dynamic Capabilities. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Lane, H.W.; White, R.E. An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, R.; Ferreira, J.J.; Simões, J. Understanding Healthcare Sector Organizations from a Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 588–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, A.L.; Reay, T.; Dewald, J.R.; Casebeer, A.L. Identifying, Enabling and Managing Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliger, A.; Krieger, D.J. The Digital Transformation of Healthcare. In Knowledge Management in Digital Change: New Findings and Practical Cases; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, C.; Katz, L.F. The Race Between Education and Technology; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, F.; Bach, N. Evolutionary and Ecological Conceptualization of Dynamic Capabilities: Identifying Elements of the Teece and Eisenhardt Schools. J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I. Dynamic Capabilities: A Review of Past Research and an Agenda for the Future. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Selen, W. The Incremental and Cumulative Effects of Dynamic Capability Building on Service Innovation in Collaborative Service Organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2013, 19, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation: An Ongoing Process of Strategic Renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellström, D.; Holtström, J.; Berg, E.; Josefsson, C. Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation. J. Strategy Manag. 2022, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, T.; Schallmo, D.; Kraus, S. Strategies for Digital Entrepreneurship Success: The Role of Digital Implementation and Dynamic Capabilities. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, D. Development and Validation of a Work Domain Goal Orientation Instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1997, 57, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Yeager, D.S. Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. Mindset-Updated Edition: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfil Your Potential; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rhew, E.; Piro, J.S.; Goolkasian, P.; Cosentino, P. The Effects of a Growth Mindset on Self-Efficacy and Motivation. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1492337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Lane, H.W.; White, R.E.; Djurfeldt, L. Organisational learning: Dimensions for a theory. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 1995, 3, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Crossan, M.; Nicolini, D. Organizational Learning: Debates Past, Present And Future. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.W. Validating Instruments in MIS Research. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.; Terkawi, A. Guidelines for Developing, Translating, and Validating a Questionnaire in Perioperative and Pain Medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. Expertlnneninterviews—Vielfach Erprobt, Wenig Bedacht: Ein Beitrag Zur Qualitativen Methodendiskussion; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Sabey, T.B.; Rodell, J.B.; Hill, E.T. Content Validation Guidelines: Evaluation Criteria for Definitional Correspondence and Definitional Distinctiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 1243–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.A.; Reynolds, W.W.; Ittenbach, R.F.; Luce, M.F.; Beauchamp, T.L.; Nelson, R.M. Challenges in Measuring a New Construct: Perception of Voluntariness for Research and Treatment Decision Making. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2009, 4, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sireci, S.G.; Faulkner-Bond, M. Validity Evidence Based on Test Content. Psicothema 2014, 26, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an Acceptable Indicator of Content Validity? Appraisal and Recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisant, A.; Skehan, S.; Colombié, M.; David, A.; Aubé, C. Development and Validation of Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Abdominal Radiology. Insights Imaging 2023, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.; Storey, V.C. Empirical Test Guidelines for Content Validity: Wash, Rinse, and Repeat until Clean. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 47, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, E.; Moles, R.; Chen, T.F. Evaluation of Methods Used for Estimating Content Validity. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and Quantification of Content Validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrbnjak, D.; Pahor, D.; Nelson, J.W.; Pajnkihar, M. Content Validity, Face Validity and Internal Consistency of the Slovene Version of Caring Factor Survey for Care Providers, Caring for Co-workers and Caring of Managers. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkin, T.R.; Tracey, J.B. An Analysis of Variance Approach to Content Validation. Organ. Res. Methods 1999, 2, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hail, M.; Zguir, M.F.; Koç, M. Exploring Digital Learning Opportunities and Challenges in Higher Education Institutes: Stakeholder Analysis on the Use of Social Media for Effective Sustainability of Learning–Teaching–Assessment in a University Setting in Qatar. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, K. Future of Undergraduate Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Impact of Perceived Flexibility and Attitudes on Self-Regulated Online Learning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.G. Understanding Dynamic Capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, F. Dynamic Capabilities: A Retrospective, State-of-the-Art, and Future Research Agenda. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D.; Barnard, H.; Dunne, D. Exploring the Everyday Dynamics of Dynamic Capabilities. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual MIT/UCI Knowledge and Organizations Conference, Laguna Beach, CA, USA, 5–7 March 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dörner, O.; Rundel, S. Organizational Learning and Digital Transformation: A Theoretical Framework. In Digital Transformation of Learning Organizations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, M.; Stingl, V.; Waehrens, B.V. Making or Breaking the Business Case of Digital Transformation Initiatives: The Key Role of Learnings. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, N. Digital Transformation and Organizational Learning: Situated Perspectives on Becoming Digital in Architectural Design Practice. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 905455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Bose, I. Strategic Learning for Digital Market Pioneering: Examining the Transformation of Wishberry’s Crowdfunding Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 146, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Braathen, P.; Hannola, L. When and How the Implementation of Green Human Resource Management and Data-driven Culture to Improve the Firm Sustainable Environmental Development? Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 2726–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, A.; Song, H.-D. The Relationships of Family, Perceived Digital Competence and Attitude, and Learning Agility in Sustainable Student Engagement in Higher Education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhao, G.; Su, K. The Fit between Environmental Management Systems and Organisational Learning Orientation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 2901–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, H.-D.; Hong, A. Exploring Factors, and Indicators for Measuring Students’ Sustainable Engagement in e-Learning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjin A Tsoi, S.L.N.M.; de Boer, A.; Croiset, G.; Koster, A.S.; van der Burgt, S.; Kusurkar, R.A. How Basic Psychological Needs and Motivation Affect Vitality and Lifelong Learning Adaptability of Pharmacists: A Structural Equation Model. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2018, 23, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.; Gedera, D.; Hartnett, M.; Datt, A.; Brown, C. Sustainable Strategies for Teaching and Learning Online. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamitri, I.; Kitsios, F.; Talias, M.A. Development and Validation of a Knowledge Management Questionnaire for Hospitals and Other Healthcare Organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. The Synergistic Effect of Market Orientation and Learning Orientation on Organizational Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Expert | Country | Expertise |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | University (Professor): Knowledge management, motivation |

| 2 | Germany | University (Professor): Digital management, innovation management |

| 3 | Latvia | University (PhD, Lecturer): Employee engagement and motivation, H.R. |

| 4 | Germany | University (Assistant Professor): Innovation, digital learning |

| 5 | Germany | Freelancer (PhD): Education, German translation |

| 6 | Germany | Healthcare (Division Management): H.R. development, digital competences |

| 7 | Germany | University (Professor): Social sciences, employability skills |

| 8 | Germany | Healthcare (Department Management): Design thinking, innovation |

| 9 | Germany | University (Researcher): Future skills, education and lifelong learning |

| Question | Expert Rating | Calculated Values | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean * | CVI | |

| 1 | Mindset | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5.00 | 0.67 | ||

| 2 | Mindset | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5.56 | 0.89 | ||||

| 3 | Mindset | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5.89 | 0.89 | |||

| 4 | Mindset | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6.22 | 1.00 | ||||

| 5 | Mindset | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6.56 | 0.89 | ||||

| 6 | Mindset | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5.00 | 0.67 | ||

| 7 | Behaviour | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5.56 | 0.89 | ||||

| 8 | Behaviour | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5.00 | 0.67 | ||

| 9 | Behaviour | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6.22 | 0.89 | ||||

| 10 | Behaviour | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4.89 | 0.67 | ||

| 11 | Behaviour | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 5.67 | 0.89 | |||

| 12 | Behaviour | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6.11 | 1.00 | ||||

| 13 | Behaviour | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5.89 | 0.89 | |||

| 14 | Behaviour | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4.78 | 0.67 | ||

| 15 | Improvement | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5.44 | 0.67 | |||

| 16 | Improvement | 1 | 5 | 3 | 6.00 | 0.89 | ||||

| 17 | Improvement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5.67 | 0.89 | |||

| 18 | Improvement | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 19 | Improvement | 1 | 7 | 1 | 5.78 | 0.89 | ||||

| Dimension | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean * | CVI | HTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindset | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5.89 | 0.89 | 0.84 | |||

| Mindset | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6.22 | 1.00 | 0.89 | ||||

| Mindset | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6.56 | 0.89 | 0.94 | ||||

| Behaviour | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6.22 | 0.89 | 0.89 | ||||

| Behaviour | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6.11 | 1.00 | 0.87 | ||||

| Behaviour | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5.89 | 0.89 | 0.84 | |||

| Improvement | 1 | 5 | 3 | 6.00 | 0.89 | 0.86 | ||||

| Improvement | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 0.86 | ||||

| Improvement | 1 | 7 | 1 | 5.78 | 0.89 | 0.83 | ||||

| Average | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| Dimension | Sustained Learning * | Learning Goal Orientation * | Growth Mindset * | Organisational Learning * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mindset | 5.51 ** | 5.14 | 4.61 | 5.09 |

| 2 | Mindset | 5.47 ** | 5.32 | 4.93 | 5.11 |

| 3 | Mindset | 5.72 ** | 5.57 | 4.91 | 4.98 |

| 4 | Behaviour | 5.48 | 5.77 ** | 4.96 | 4.30 |

| 5 | Behaviour | 5.71 ** | 5.36 | 5.54 | 4.51 |

| 6 | Behaviour | 5.34 | 5.21 | 5.40 ** | 4.71 |

| 7 | Improvement | 5.48 | 5.74 ** | 4.88 | 4.27 |

| 8 | Improvement | 5.13 | 5.31 ** | 4.59 | 4.30 |

| 9 | Improvement | 4.46 | 4.47 ** | 4.42 | 4.05 |

| Fit Measure | Result | Acceptable Fit | Good Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 34.2 | 2df < χ2 ≤ 3df | 0 ≤ χ2 ≤ 2df 0 ≤ 34.2 ≤ 38 |

| p | 0.018 | 0.01 ≤ p ≤ 0.05 0.01 ≤ 0.018 ≤ 0.05 | 0.05 < p ≤ 1.00 |

| df | 19 | ||

| χ2/df | 1.8 | 2 < χ2/df ≤ 3 | 0 ≤ χ2/df ≤ 2 0 ≤ 1.8 ≤ 2 |

| Subdimension | Survey Item |

|---|---|

| Individual attitude: Open mindset to explore new things—Accept. | If there are conversations and discussions about new technologies in my environment, I am interested in them. |

| If someone tells me about new ideas to use technology, I am open to them. | |

| If there are new technologies or tools that make my work easier, I want to know more about them. | |

| Behavioural pattern: Questioning habits and routines—Act and Reflect. | I watch explanation videos (e.g., on YouTube or other platforms) and/or read additional instructions to improve my knowledge. |

| When I learn something new about digital technologies, I rethink my previous actions and try to develop them further with the new knowledge. | |

| If situations are changing, I adapt my decisions and activities regarding the use of digital technologies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Starke, S.; Ludviga, I. Impeding Digital Transformation by Establishing a Continuous Process of Competence Reconfiguration: Developing a New Construct and Measurements for Sustained Learning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310218

Starke S, Ludviga I. Impeding Digital Transformation by Establishing a Continuous Process of Competence Reconfiguration: Developing a New Construct and Measurements for Sustained Learning. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310218

Chicago/Turabian StyleStarke, Sandra, and Iveta Ludviga. 2024. "Impeding Digital Transformation by Establishing a Continuous Process of Competence Reconfiguration: Developing a New Construct and Measurements for Sustained Learning" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310218

APA StyleStarke, S., & Ludviga, I. (2024). Impeding Digital Transformation by Establishing a Continuous Process of Competence Reconfiguration: Developing a New Construct and Measurements for Sustained Learning. Sustainability, 16(23), 10218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310218

_Lu.png)