1. Introduction

In the last two decades, emerging technologies associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution have significantly transformed the labor landscape. Although remote work is not a new phenomenon, the COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a catalyst, forcing many organizations to abruptly implement this modality [

1,

2]. As a result, telework has become a highly relevant and current issue [

3], experiencing rapid expansion [

4] and pushing many companies to adopt hybrid and remote work models [

1,

5].

According to the authors of [

6], in the European Union, the number of teleworkers reached 41.7 million in 2021, doubling the figures reported in 2019. Despite a slight decline in 2022, this upward trend is expected to continue, driven by advances in information technology and companies’ growing preference for remote work.

In North America, particularly in the United States and Canada, remote and hybrid employment opportunities have experienced steady growth over the last decade, reaching 12% in 2023. This trend is expected to be irreversible. In the post-pandemic period, the sectors that experienced the greatest increase in remote work included IT services, financial operations, legal and administrative areas, architecture and engineering, social sciences, arts, and entertainment [

2].

In Peru, the National Civil Service Authority (SERVIR) conducted a comprehensive study in 2021 on the implementation of remote work in the public sector. This research, which involved 10,563 civil servants and 703 line managers and support area heads from 27 public institutions across the three levels of government, revealed significant disparities in the adoption of telework. In national and regional governments, remote work prevailed (52% and 46%, respectively), as did hybrid work (43% and 35%, respectively), whereas in local governments, 48% of staff remained in onsite roles [

7]. Additionally, the Ministry of Labor and Employment Promotion (MTPE) reported in 2023 that approximately 5% of formal private-sector workers (in the service, trade, and manufacturing sectors) continue to engage in remote work.

Importantly, telework is known under various names, including remote work, virtual work, flexible work, and distance work. This work modality is characterized by performing tasks outside the employer’s premises, generally from home, using information and communication technologies (ICTs) to interact with colleagues and fulfill job responsibilities [

8,

9,

10,

11].

The use of ICTs in telework not only facilitates daily work operations but also directly contributes to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, ICTs support SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by enabling remote work opportunities that promote sustainable economic growth and productive employment. They also advance SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) by fostering digital infrastructure development and increasing access to information technologies. Furthermore, ICTs contribute to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by democratizing work opportunities across geographical locations and reducing urban–rural divides in employment access [

12]. The widespread adoption of digital platforms, cloud computing, and collaborative tools has transformed telework from a mere alternative work arrangement into a sustainable and efficient work paradigm. This transformation is particularly evident in how ICTs enable seamless communication, project management, and knowledge sharing while simultaneously reducing the environmental impact associated with traditional office-based work through decreased commuting and office space requirements. The accessibility and affordability of internet services have become crucial factors in the success of telework implementation, with organizations investing significantly in digital infrastructure to ensure reliable connectivity and secure access to work resources. This technological foundation has proved especially valuable during global disruptions, demonstrating telework’s resilience as a sustainable work model that can maintain productivity while promoting social inclusion and environmental sustainability.

In the Peruvian legal framework, the Telework Law defines this modality as a special form of service provision, performed regularly or habitually, characterized by the worker’s physical absence from the workplace and the use of ICT [

12].

Most research on telework has focused on the private sector, with few studies examining the effects of telework on job satisfaction and quality of life for public sector employees. Furthermore, the moderating role that quality of life might play in this relationship within the public sector context has not been clearly elucidated. This hypothesis has not been empirically tested in governmental organizations, where working conditions could differ significantly. Therefore, it is imperative to address this knowledge gap to better understand how to manage telework in public entities.

Consequently, the present research aims to answer the following question: does quality of life act as a moderator in the relationship between telework and job satisfaction among public sector employees? This research is justified from three fundamental perspectives: theoretical, as it seeks to fill existing knowledge gaps in the literature on telework in the public sector; practical, as it provides valuable information that can be used by public entities to formulate more effective telework policies and practices tailored to their specific context; and social, by considering the well-being and satisfaction of public employees, thus contributing to improving working conditions and the quality of life for this important sector of the workforce.

After these significant gaps in the current literature are identified, it is essential to establish a robust theoretical framework to support our research. This framework allows us to systematically and rigorously address the complex interrelationships among telework, job satisfaction, and quality of life, specifically within the public sector. Below is a comprehensive and critical review of key concepts, relevant theories, and previous empirical studies that will inform our methodological approach and guide the interpretation of the results. This theoretical framework not only provides a solid conceptual foundation for our study but also helps contextualize our findings within the broader body of knowledge on telework and its implications in organizational settings, with a particular focus on the unique dynamics and challenges of the public sector. This theoretical foundation will enable us to address the research questions more precisely and contribute significantly to advancing knowledge in this field.

For the purposes of this study, the dimensions of telework were conceptualized on the basis of [

8] work. These dimensions include flexible schedules, which refer to the autonomy that teleworkers have to manage their schedules on the basis of assigned tasks and company-set goals; working from anywhere, which involves the ability to perform work responsibilities outside conventional premises; the use of personal devices, which entails the use of new technologies to facilitate communication between teleworkers and employers; results-based evaluation, which is defined as the systematic monitoring and control system implemented by the company; and virtual meetings with unlimited participants, which refers to the corporate virtual space accessible via ICT.

Ref. [

13] conceptualized job satisfaction as a subjective assessment influenced by various factors, including the work environment, personal development, job stability, and the appreciation of work, including remuneration. Ref. [

14] described it as a set of positive feelings derived from workers’ perceptions of their jobs, influenced by aspects such as salary, professional projection, autonomy, and incentives. Both perspectives emphasize that job satisfaction emerges from comparing real work with ideal work and is influenced by both personal factors and working conditions.

Ref. [

14] proposed three main dimensions of job satisfaction: satisfaction with the physical environment, which encompasses all essential elements necessary to perform the job optimally; satisfaction with supervision, which refers to the evaluation and monitoring policies overseeing employees’ daily work; and satisfaction with benefits, which includes the level of compensation with which the organization values and rewards the service provided by the worker.

The scientific literature has extensively explored the influence of telework on job satisfaction. Ref. [

15] suggested that changes in work organization practices, including flexible work arrangements, can significantly impact workers’ well-being. In this context, Ref. [

16] reported that in Russia, working from home has a positive effect on job satisfaction as long as it does not exceed eight hours a day since longer workdays could decrease satisfaction.

Several studies have highlighted that telework can be a valuable tool for balancing work and family life, offering individuals the opportunity to organize work around their lives, which improves quality of life and, consequently, workers’ well-being [

17,

18]. Ref. [

19] reported a positive relationship between telework and the well-being of remote workers, associating it with positive emotions, increased job satisfaction, and organizational commitment while also improving feelings of emotional exhaustion. In terms of professional well-being, remote workers demonstrate greater autonomy, which is corroborated by [

20], who asserted that telework provides workers with greater autonomy, control, and flexibility.

However, the effects of telework are not uniformly positive and may present contradictory results in key organizational aspects such as job satisfaction [

21,

22]. This variability is particularly relevant, considering that job satisfaction is closely related to worker performance and productivity (Memon et al., 2023 [

23,

24]). Ref. [

19] identified several negative aspects associated with telework, such as social and professional isolation and the perception of threats to career advancement. Additionally, Ref. [

25] suggested that the autonomy and flexibility provided by remote work could also intensify work demands and work–family conflict, potentially reducing satisfaction.

Empirical evidence suggests that telework has mixed impacts on job satisfaction. On the one hand, it can reduce the stress associated with commuting and improve work-life balance [

26,

27]. However, on the other hand, it can generate feelings of isolation and reduce team cohesion [

28]. A systematic review by [

29] revealed mixed consequences for employee performance and well-being, indicating that remote work affects employees’ perceptions of themselves and their workplaces, contributing to their physical and mental health, particularly in terms of work-life balance.

In the Peruvian context, Ref. [

7]’s study revealed that performance levels between remote and onsite work remained the same for 52% of public servants, whereas 41% considered it improved. Ref. [

18] indicated that various factors can influence remote work, so companies must adopt unique strategies reflecting their specific situation. Ref. [

30] reported that organizations with telework-related policies shape communication flows between employees and managers, whereas those that allow telework only as an exception, without valuing it or establishing regulatory policies, create different performance outcomes for teleworkers.

Ref. [

31], in a study conducted in Brazil, highlighted that access to technology, establishing a relationship of trust, and ensuring professional growth can increase the self-esteem of remote workers. This occurs when the organization and its leaders set clear goals, implement training plans, support well-being, and foster professional and social integration. The sense of professional fulfillment intensifies when telework is a personal choice that provides a sustainable balance between personal and professional life without creating a sense of social isolation.

Ref. [

32] emphasized that for a telework program to succeed, leaders, managers, and supervisors must provide consistent and substantial information to support teleworkers. It is necessary to develop legal and political guidelines that encourage cooperation, collaboration, and virtual interactions with and among teleworkers, as they can easily feel isolated due to the lack of interaction with colleagues. Establishing cultural norms is desirable in the workplace, as a high-performance policy can be developed. When teleworkers become aware of these cultural norms and leadership strives to evaluate their performance accurately and objectively, performance management expectations are clearly set.

Quality of life is intrinsically related to workers’ physical, psychological, and social well-being [

21]. Dimensions of quality of life, such as physical and mental health, work stress, sleep disorders, and balancing work life with family roles, interact with telework implementation, shaping its effect on workers’ satisfaction with their employment [

33,

34]. In this sense, a higher quality of life could buffer the potentially negative effects of telework on satisfaction by providing a more favorable personal environment.

The literature on telework and its effects on job satisfaction reveals a significant gap in knowledge, particularly concerning the public sector. This gap is manifested in several key aspects: most research has focused on the private sector, leaving a noticeable scarcity of studies examining the specific effects of telework on job satisfaction and quality of life among public sector employees; the moderating role of quality of life in the relationship between telework and job satisfaction in the public sector context has not been clearly elucidated; there is a lack of understanding of how telework policies and practices in the public sector can be designed and adapted to maximize job satisfaction and quality of life for employees; the long-term impact of telework on the organizational culture of public entities and how this affects job satisfaction and quality of life has been underexplored; and there is a shortage of longitudinal studies examining how the relationships among telework, job satisfaction, and quality of life evolve in the public sector over time. Addressing these gaps is crucial for better understanding how to effectively and sustainably manage telework in public entities, as research in this area has not only significant theoretical implications but also provides valuable insights for formulating policies and practices that improve both the organizational efficiency and the well-being of public employees. Consequently, this research aims to answer the question of whether quality of life acts as a moderator in the relationship between telework and job satisfaction among employees of a public entity. The research is justified from theoretical, practical, and social perspectives, aiming not only to contribute to the academic body of knowledge but also to provide practical insights that can inform decision-making in the public sector, thereby improving the implementation and management of telework for the benefit of both organizations and their employees.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was conducted via a quantitative approach with an explanatory scope and a nonexperimental cross-sectional design. A structural equation modeling (SEM) model was used with the Smart Partial Least Squares (PLS) version 4 tool to analyze the relationships between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life. The quantitative approach was selected because of its ability to provide generalizable and quantifiable results. The explanatory scope allowed for understanding causal relationships between the variables, whereas the nonexperimental cross-sectional design facilitated data collection at a specific point in time, offering an instant snapshot of the relationships between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life. Advanced statistical analysis techniques were employed to assess the reliability and validity of the constructs involved and to test the hypotheses.

2.2. Sample

The unit of analysis consisted of employees from the National University Pedro Ruiz Gallo in Lambayeque. To ensure the representativeness of different sectors and levels of experience within the university, stratified random sampling was used. This approach allowed the population to be divided into homogeneous subgroups (strata), and then random samples were selected from each of these subgroups, ensuring an equitable and representative distribution. In total, data were collected from 194 respondents who met the inclusion criteria of the study.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: being an active employee of the National University Pedro Ruiz Gallo, having at least six months of experience at the institution, and voluntarily participating in the study. The exclusion criteria included employees with less than six months of experience at the institution, employees who did not complete the questionnaire in its entirety, and employees on extended leave or permission during the data collection period. These criteria were verified through a prior review of human resources records, ensuring that only employees who met the requirements participated in the study.

2.4. Measurement Instruments

A structured questionnaire was used for data collection, which was validated by a panel of 5 experts in relevant topics and methodologies. The validity of the questionnaire was determined via [

35] content validity criterion, which yielded a concordance index of 0.83, indicating high content validity. The questionnaire covered the following variables:

Telework: measured through 17 items assessing the amount of time working from home, the quality of the telework experience, and the availability of adequate resources such as internet connections and appropriate computers.

Job Satisfaction: measured by 8 items measuring job independence, work-life balance, and perceived effectiveness in task performance.

Quality of Work Life: assessed by 14 items measuring the level of stress, health status, and professional development opportunities perceived by employees.

Prior to full implementation, a comprehensive pilot study was conducted with 50 employees (n = 50) from the institution (not included in the final sample) during November 2023. The pilot testing evaluated instrument validity, reliability, and feasibility using rigorous statistical analysis. The results showed strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.912 for telework (17 items), 0.897 for job satisfaction (8 items), and 0.885 for quality of work life (14 items). All items demonstrated significant factor loadings (p < 0.001) with values ranging from 0.721 to 0.896. The pilot study also yielded favorable composite reliability indices (CR > 0.80) and average variance extracted values (AVE > 0.50) for all constructs. Additionally, item–total correlations ranged from 0.683 to 0.842, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.30. Response time averaged 18.5 min (SD = 3.2), which was deemed acceptable by participants. Based on pilot feedback, minor refinements were made to improve item clarity and response options, particularly in the telework dimension. The pilot study’s robust psychometric properties and positive participant feedback provided strong support for the instrument’s implementation in the main study.

2.5. Data Sociodemographic

In addition to the main variables, sociodemographic data were collected to provide a broader context and analyze possible moderating effects. Sociodemographic variables included age, gender, type of contract, level of education, marital status, and years working in the organization.

2.6. Procedure

The questionnaires were administered in a physical format and self-administered, ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of the responses. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, assured that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without repercussions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before they completed the questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed and collected in a manner that minimized any possibility of identifying the participants.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles while aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). The research protocol received approval from both the Ethics Committee of the National University Pedro Ruiz Gallo (Approval No. UNPRG-2024-015, dated 15 January 2024) and the Institutional Sustainability Committee (ISC-2024-008). The research design incorporated sustainable practices through digital data collection methods and virtual consent processes, reducing environmental impact while maintaining scientific rigor. Data protection and participant confidentiality were ensured through encrypted digital systems and secure, energy-efficient servers. Special attention was given to digital well-being, cybersecurity, and the protection of vulnerable groups, ensuring equitable participation regardless of technological access. Informed consent procedures emphasized both individual and environmental benefits, while participants retained the right to withdraw at any time without consequences. The study methodology adhered to international standards for sustainable research and data protection regulations, balancing scientific objectives with environmental responsibility and participant well-being. All collected data were anonymized and stored securely, with particular attention to protecting participants’ digital privacy and work–life balance during the research process.

2.8. Data Analysis

2.8.1. Reliability and Validity of the Constructs

To ensure the robustness of the model, the reliability and validity of the main constructs—quality of work life, telework, and job satisfaction—were evaluated. Reliability indicators such as Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, as well as the average variance extracted (AVE), were used for these evaluations. The results showed that the constructs of quality of work life and telework had issues with discriminant validity, whereas job satisfaction demonstrated good discriminant validity. Overall, the reliability of the constructs was acceptable, but areas for improvement were identified in the differentiation between the quality of work life and telework constructs.

2.8.2. Discriminant Validity

The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to assess discriminant validity. The results indicated that while job satisfaction showed good discriminant validity, the constructs of quality of work life and telework presented challenges in this respect. This suggests that the items in these constructs may capture similar dimensions, requiring a review and possible refinement of the items used to measure these variables.

2.9. Methodological Conclusion

The methodology used in this study, which is based on structural equation modeling with Smart PLS version 4, allows for a precise evaluation of the relationships between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life. Rigorous statistical analyses ensured the reliability and validity of the constructs, and the model fit indices confirmed their robustness. Additionally, the inclusion of sociodemographic data provided a broader context and allowed for the analysis of relevant moderating effects. These findings offer a solid foundation for interpreting the relationships between these variables and provide valuable recommendations for future research and practical applications in the context of telework and its impact on job well-being.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Participants (N = 194)

The analysis of participant characteristics (

Table 1) reflects the current reality of higher education institutions. Women made up more than half of the workforce (57.7%), while the predominant age group was between 35 and 44 years (37.6%), representing professionals in their peak career stage. Most participants had advanced degrees, with more than half holding graduate qualifications, reflecting the academic nature of the institution. Job stability emerged as a significant factor, with nearly three-quarters of participants holding permanent positions. Interestingly, organizational experience showed a balanced distribution, though the largest group (32.5%) had been with the institution for 5–10 years. This mix of experience levels and academic backgrounds provides valuable insights into how different employee groups adapt to telework arrangements. The demographic profile suggests a workforce that combines professional maturity with academic expertise, key elements for understanding telework dynamics in university settings. These characteristics helped frame our understanding of how telework practices are adopted and maintained in academic environments.

3.2. Reliability and Validity of the Construct

To ensure the robustness of the proposed model, the reliability and validity of the main constructs—quality of work life, telework, and job satisfaction—were evaluated. The results of these evaluations are presented below, which are based on Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (rho_a rho_c), and the average variance extracted (AVE).

Quality of work life showed adequate reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.742, indicating acceptable internal consistency among the items that make up this variable. The composite reliability (rho_a) was 0.824, and rho_c was 0.746, suggesting good composite reliability of the construct. The AVE of 0.587 indicated that more than half of the variance of the items was explained by the construct, thus confirming adequate convergent validity. For telework, this construct also showed acceptable reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.759, reflecting good internal consistency among the items. The composite reliability rho_a was 0.769, and rho_c was 0.729, indicating satisfactory composite reliability. The AVE of 0.594 implied that a considerable proportion of the items’ variance is captured by the telework construct, supporting its convergent validity. Job satisfaction presented high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.851 indicating excellent internal consistency. The composite reliability rho_a was 0.854, and rho_c was 0.886, suggesting very robust composite reliability. The AVE of 0.596 showed that a significant portion of the items’ variance is explained by the construct, confirming its convergent validity. In conclusion, the results of the reliability and validity evaluations demonstrate that the constructs of quality of work life, telework, and job satisfaction are both reliable and valid. The values of Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (rho_a and rho_c), and AVE exceed acceptable thresholds, suggesting that the items used to measure these constructs are consistent and adequately capture the underlying theoretical dimensions. These findings strengthen confidence in the interpretations and conclusions drawn from the proposed model, providing a solid foundation for future research and practical applications in the context of telework and its impact on workplace well-being (

Table 2).

To assess the discriminant validity of the model (

Table 3), the Fornell–Larcker criterion was used, which compares the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with the correlations between the constructs. The results of this evaluation are described below. For quality of work life, the square root of the AVE was 0.536. Compared with the correlations of 0.571 with telework and 0.614 with job satisfaction, the square root of the AVE is lower than these correlations. This suggests that quality of work life is not clearly distinguished from the other constructs, indicating potential problems with discriminant validity. For telework, the square root of the AVE was 0.542. Compared with the correlations of 0.571 with quality of work life and 0.584 with job satisfaction, the square root of the AVE is also lower. This finding indicates that telework is not clearly differentiated from the other constructs, raising similar discriminant validity issues as those found with quality of work life. With respect to job satisfaction, the square root of the AVE was 0.704. Compared with the correlations of 0.614 with quality of work life and 0.584 with telework, the square root of the AVE is greater. This demonstrates that job satisfaction is adequately distinguished from the other constructs, showing good discriminant validity. In conclusion, the results of the discriminant validity evaluation using the Fornell–Larcker criterion are mixed. At the same time, job satisfaction is clearly distinguished from the other constructs; quality of work life and telework present issues with discriminant validity. The square root of the AVE for these two constructs is lower than their correlations with other constructs, suggesting that they are not clearly differentiated from each other. These findings highlight the need to review and possibly refine the items used to measure the quality of work life and telework to improve their discriminant validity. Despite these issues, job satisfaction remains a valid and differentiated construct within the model. Refining the measurement instruments could further strengthen the reliability and validity of the model, providing a more robust foundation for future research and practical applications in the context of telework and its impact on workplace well-being.

To evaluate collinearity within the model, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used. This statistic helps to identify potential multicollinearity issues that could affect the accuracy of parameter estimates in the model. The results of this evaluation are presented below (

Table 4). In terms of the relationship between telework and quality of work life, the variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.517. This value indicates that there is no significant collinearity issue, as the VIF is below the commonly accepted threshold of 5. This suggests that teleworking can be considered a valid and reliable predictor of quality of work life without concerns of excessive collinearity. For the relationship between telework and job satisfaction, the variance inflation factor (VIF) is 2.324. Although this value is greater than the previous relationship, it is still below the critical threshold of 5. This indicates that while there is some collinearity, it is not strong enough to compromise the model’s validity. Therefore, teleworking can also be considered a reliable predictor of job satisfaction. In the relationship between job satisfaction and quality of work life, the variance inflation factor (VIF) is again 1.517. This value reinforces the idea that there are no significant collinearity issues in this relationship, allowing job satisfaction to be a robust predictor of quality of work life. The results of the VIF analysis indicate that there are no significant collinearity issues in the internal model. The VIF values for the relationships between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life are all below the critical threshold of 5, suggesting that the parameter estimates are accurate and reliable. This strengthens the model’s validity and provides a solid foundation for interpreting the relationships between these key variables. The absence of significant collinearity ensures that the conclusions derived from the model are robust and reliable, offering valuable insights into the impact of teleworking on workplace well-being.

3.3. Proposed Model

The model developed by researchers consists of three main components:

Telework: This component evaluates various aspects related to remote work, such as the amount of time employees work from home and the quality of that experience. The availability of adequate resources, such as good internet connections and appropriate computers, is also considered, particularly in the Lambayeque region.

Job Satisfaction: This aspect of the model measures the degree of worker satisfaction in relation to their independence, their ability to balance work and personal life, and their perception of effectiveness in performing their tasks.

Quality of Work Life: This evaluates elements such as stress levels, health status, and perceived opportunities for professional development by employees.

A key element of the model is the inclusion of moderating variables, which are characteristics that can influence the relationships among the model’s main components. In this case, the moderating variables are as follows:

These moderating variables play crucial roles in the model, as they help us understand whether the impact of telework on job satisfaction and quality of work life varies depending on employees’ work experience and gender. For example, it is possible that teleworking has different effects on individuals with many years of experience than on those who have just started their professional careers.

Researchers posit that telework directly influences the degree of job satisfaction and employees’ perceptions of quality of work life. Additionally, they consider that greater job satisfaction, derived from good teleworking experience, can improve the overall perception of quality of work life. The moderating variables help to better understand these relationships and determine whether these effects are consistent for all workers or vary depending on experience and gender.

This study is highly relevant for the National University Pedro Ruiz Gallo (UNPRG) and the Lambayeque region. It offers a deeper understanding of how telework is transforming work dynamics, not only in this region but also throughout Peru. The findings of this study can provide valuable information for companies and government authorities to make more informed decisions about telework, considering the diverse needs of workers on the basis of their experience and gender.

As a project that involves the entire university, this study demonstrates how the UNPRG integrates efforts from different areas of knowledge to investigate contemporary and important topics. The results will not only be of interest to other researchers but also help companies and organizations in Lambayeque improve telework management, promoting greater satisfaction and better work performance, considering the differences among various groups of workers.

3.4. Direct Hypotheses

The proposed model (

Figure 1) examines the direct relationships between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life, revealing significant results across all the hypothesized relationships. The first relationship, between telework and quality of work life, has a standardized coefficient of 0.32, a t value of 4.18, and a

p value of 0.000. These results indicate a positive and significant relationship, suggesting that greater adoption of telework is associated with improved quality of life at work. In other words, as workers increase their time and quality in telework, they experience a notable increase in their perceived well-being at work. The second relationship between teleworking and job satisfaction is also positive and significant, with a standardized coefficient of 0.38, a t value of 4.76, and a

p value of 0.000. This finding indicates that teleworking significantly contributes to higher job satisfaction. Employees who telework tend to feel more satisfied with their independence and their ability to balance work and personal life. Finally, the relationship between job satisfaction and quality of work life is the strongest of the three, with a standardized coefficient of 0.42, a t value of 5.99, and a

p value of 0.000. This suggests that employees who are more satisfied with their jobs also perceive a better quality of work life. Thus, job satisfaction becomes a key element in improving the overall perception of workplace well-being (

Table 5).

3.5. Mediation Hypothesis

The model also evaluates the mediation hypothesis, where job satisfaction acts as a mediator between telework and quality of work life. Mediation has a standardized coefficient of 0.16, a t value of 3.67, and a

p value of 0.000, indicating a significant relationship (

Table 6). This suggests that part of the positive effect of telework on the quality of work life is explained through an increase in job satisfaction. Essentially, teleworking not only has a direct effect on the quality of work life but also exerts an indirect effect by increasing job satisfaction, underscoring the importance of keeping employees satisfied to enhance their overall well-being.

3.6. Moderating Hypotheses

The model also examines how gender and years of work experience moderate the relationships between telework and job satisfaction. The interaction between gender and telework has a standardized coefficient of 0.27, a t value of 2.41, and a

p value of 0.016, indicating a significant relationship (

Table 7). This suggests that the impact of telework on job satisfaction varies according to worker gender. In other words, telework may have different effects on men and women, highlighting the need to consider gender when implementing telework policies. On the other hand, the interaction between years of work experience and telework presents a standardized coefficient of −0.11, a t value of 2.38, and a

p value of 0.017, which is also significant. This finding indicates that the impact of telework on job satisfaction decreases as work experience increases. Workers with more years of experience may have different perceptions of telework than those who are at the beginning of their careers, emphasizing the importance of tailoring telework strategies to employees’ experience levels.

Collectively, these results underscore the relevance of telework as a factor that positively influences both job satisfaction and quality of work life. Furthermore, job satisfaction plays a crucial mediating role in this relationship, demonstrating that improved telework experience can lead to greater satisfaction, which in turn enhances the quality of work life. Moderating variables, such as gender and years of work experience, also play a significant role, showing that the effect of telework is not uniform and varies according to individual characteristics. This study provides a deeper understanding of how telework can be optimized to improve worker well-being, considering individual differences. The findings of this study can be useful for companies and government authorities in making more informed decisions about telework, ensuring that policies are inclusive and tailored to the diverse needs of workers.

To evaluate the adequacy of the proposed model, various fit indices were employed to compare the saturated model with the estimated model (

Table 8). The results reveal that both models fit the observed data well. The root mean square residual (SRMR) for the saturated model is 0.050, whereas for the estimated model, it is 0.055. Since these values are below the 0.08 threshold, they indicate minimal discrepancies between the observed and predicted correlations. This suggests a high level of precision in the fit of both models, which is crucial for ensuring the reliability of the conclusions drawn.

The d_ULS (square Euclidean distance) is 2.000 for the saturated model and 2.200 for the estimated model. These low values suggest a minimal squared Euclidean distance between the observed and predicted matrices, indicating that both models fit the data well. The slight difference between the two models implies that the estimated model maintains a similar fit to the saturated model with an insignificant variation. The d_G (geodesic distance) is 1.000 for the saturated model and 1.200 for the estimated model, reinforcing the robustness of the model fit with a low geodesic distance between the observed and predicted matrices. This means that the discrepancies between the observed and predicted data are minimal, ensuring model reliability. With respect to the chi-square statistic, the values obtained are 500.000 for the saturated model and 520.000 for the estimated model. These low values suggest a good correspondence between the observed and predicted covariance matrices. The small difference between the two values indicates that the estimated model has nearly the same fit as the saturated model, with an insignificant degradation in fit.

The normed fit index (NFI) is 0.900 for the saturated model and 0.890 for the estimated model. These values, which are close to the 0.90 threshold, indicate an acceptable model fit compared with a null model. The proximity of these values suggests that both models fit well, although the saturated model shows a marginally better fit. Overall, the results of the fit indices demonstrate that both the saturated and estimated models fit the observed data well. The SRMR and NFI indicate high precision and model adequacy, whereas the d_ULS and d_G reinforce the robustness of the fit by showing low discrepancies between the observed and predicted matrices. Although the chi-square statistic is slightly higher in the estimated model, it still indicates good correspondence between the covariance matrices.

The estimated model provides an accurate and reliable representation of the relationships between the study variables. The high quality of the model fit ensures that the interpretations of the relationships between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life are sound, offering a reliable foundation for future research and practical applications in the context of telework and its impact on employee well-being.

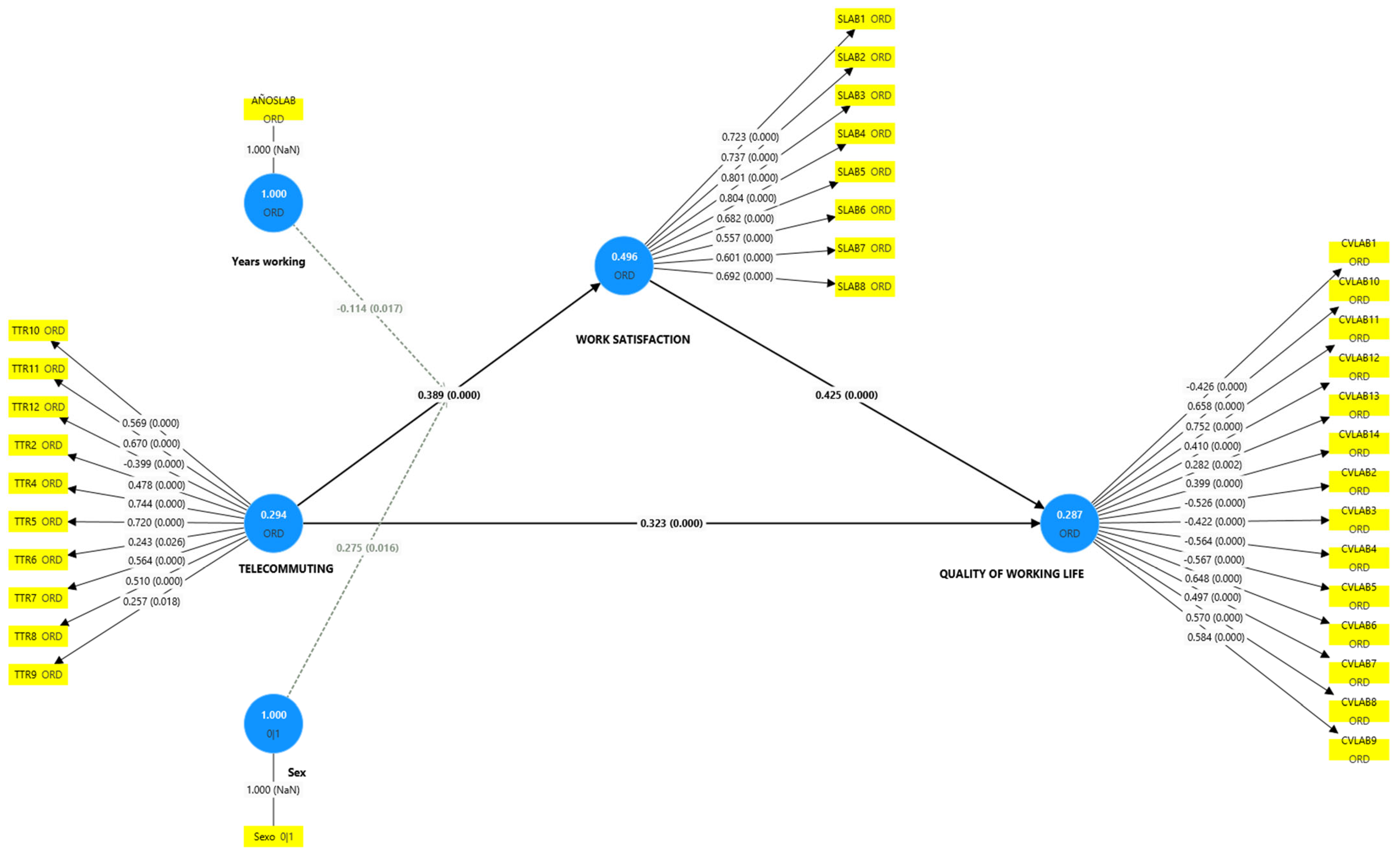

3.7. Resolved Model

The resulting model provides (

Figure 2) a clear and comprehensive understanding of how teleworking influences job satisfaction and quality of work life, with several key findings. The model demonstrates a positive and significant relationship between telework and job satisfaction, with a standardized coefficient of 0.389 and a

p value below 0.001, indicating that as telework experience increases, employees report greater job satisfaction, likely due to benefits such as autonomy, flexibility, and work-life balance. Moreover, the direct relationship between telework and quality of work life is also positive and significant, with a standardized coefficient of 0.323 and a

p value below 0.001, suggesting that telework not only enhances job satisfaction but also directly improves the perception of work–life quality, likely due to reduced commuting time and greater flexibility in managing personal and professional responsibilities. The model also shows that job satisfaction positively influences the quality of work life, with a standardized coefficient of 0.425 and a

p value below 0.001, acting as a mediator between telework and work–life quality—indicating that higher job satisfaction, driven by telework, significantly boosts work–life quality, highlighting job satisfaction as a key component of overall employee well-being.

Additionally, the model includes moderating variables such as years of work experience and gender, revealing that the impact of telework on job satisfaction may decrease with more years of experience (coefficient: −0.114, p value: 0.017), possibly due to differing expectations among more experienced employees, whereas the interaction between gender and telework (coefficient: 0.275, p value: 0.016) shows that telework can differentially impact job satisfaction on the basis of gender, underscoring the importance of considering individual differences when implementing telework policies. Overall, the model provides a deep understanding of the dynamics between telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life, demonstrating that telework positively impacts both job satisfaction and quality of work life, with job satisfaction playing a mediating role. The moderating effects of work experience and gender emphasize the need for tailored telework policies to maximize their benefits, offering practical recommendations for organizations and policymakers to improve employee well-being through effective telework strategies that account for individual differences.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide a comprehensive and nuanced view of the dynamics of telework in the Peruvian public sector, significantly contributing to the literature and offering important practical implications. The following sections delve deeper into the discussion of the results, considering additional aspects and contextualizing the findings within the broader framework of telework research.

The positive and significant relationship found between telework and job satisfaction (β = 0.389,

p < 0.001) not only confirms the findings of previous studies but also offers new perspectives in the specific context of the Peruvian public sector. This finding is particularly relevant considering the [

7], which revealed unequal adoption of telework at different levels of the Peruvian government. Our results suggest that, despite these disparities, telework has a positive effect on public employees’ job satisfaction.

However, it is important to contextualize this finding with the observations of Ray and [

15], who noted that changes in work organization practices, including flexible work arrangements, can significantly affect workers’ well-being. In this sense, our study provides empirical evidence of how these changes, specifically telework, positively impact the Peruvian public sector.

Furthermore, it is crucial to consider the warnings of [

25], who suggested that the autonomy and flexibility provided by remote work could also intensify work demands and work–family conflict. Although our results reveal an overall positive impact, future research could further explore these potential negative effects in the specific context of the Peruvian public sector.

- 2.

Telework and quality of work life

The positive relationship between telework and quality of work life (β = 0.323,

p < 0.001) is consistent with the findings of [

29], who, in their systematic review, revealed diverse and mixed outcomes of remote work on employees’ performance and well-being. Our study contributes to this line of research by providing specific evidence from the Peruvian public sector, a context that has been underexplored in the literature.

Importantly, our findings somewhat contrast with the concerns raised by [

28] regarding the potential of telework to generate feelings of isolation and reduce team cohesion. This discrepancy could be due to the specific characteristics of the Peruvian public sector or the manner in which telework has been implemented in this context. Future studies could further explore these aspects to better understand how the potential negative effects of telework on team cohesion and employees’ sense of connection can be mitigated.

- 3.

The mediating role of job satisfaction

The finding that job satisfaction acts as a mediator between telework and quality of work life (β = 0.425,

p < 0.001) is particularly significant and adds a new dimension to the understanding of how telework influences employees’ well-being. This result is consistent with the theory of [

23], who emphasize the close relationship between job satisfaction and workers’ performance and productivity.

Moreover, these findings have important implications for the management of telework in the public sector. This suggests that strategies aimed at improving teleworkers’ job satisfaction could have a multiplier effect, enhancing not only their immediate satisfaction but also their overall quality of work life. This aligns with the recommendations of [

32], who stressed the importance of consistent support from leaders and managers to ensure the success of telework programs.

- 4.

Moderating variables: work experience and gender

The finding that work experience negatively moderates the relationship between telework and job satisfaction (β = −0.114,

p = 0.017) is particularly novel and deserves further exploration. This result could be related to the observations of [

31], who highlighted the importance of factors such as access to technology, trust-based relationships, and professional growth assurances in boosting teleworkers’ self-esteem.

It is possible that more experienced employees face greater challenges in adapting to new technologies and work practices associated with telework, which could explain the reduced positive impact of telework on their job satisfaction. This finding underscores the need for training and support programs specifically designed for more experienced employees in the context of telework.

On the other hand, the positive moderating effect of gender on the relationship between telework and job satisfaction (β = 0.275,

p = 0.016) is consistent with previous studies that have reported gender differences in telework experience. However, our study adds a new perspective in the specific context of the Peruvian public sector. This finding could be related to the observations of [

27] on how telework can reduce the stress associated with commuting and improve work-life balance, factors that may have differential impacts by gender due to different responsibilities and social expectations.

- 5.

Implications for practice and public policy

Our findings have important implications for the management of telework in the Peruvian public sector. First, they suggest that teleworking can be an effective tool to improve job satisfaction and quality of work life for public employees. However, the implementation of telework must be carefully considered and tailored to the individual characteristics of employees, considering factors such as work experience and gender.

Additionally, our results underscore the importance of maintaining and improving the job satisfaction of teleworkers as a means of enhancing the overall quality of work life. This aligns with the recommendations of [

36], who emphasized the importance of work-life balance measures to prevent voluntary employee turnover.

- 6.

Limitations and future directions

Despite its significant contributions, this study has several limitations that should be considered. First, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish definitive causal relationships. Future longitudinal studies could provide a deeper understanding of how the relationships among telework, job satisfaction, and quality of work life evolve over time.

Furthermore, although our study focused on the Peruvian public sector, future research could explore how these findings compare with those of the private sector or other countries in the region. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how organizational and cultural contexts influence the effectiveness of telework.

In conclusion, this study provides solid evidence of the positive impact of telework on job satisfaction and quality of work life in the Peruvian public sector. However, it also reveals the complexity of these relationships, highlighting the importance of considering individual and contextual factors in the implementation of telework. These findings not only contribute to the academic body of knowledge on telework but also offer valuable insights for the formulation of telework policies and practices in the public sector.

5. Conclusions

The research demonstrates significant findings about telework effects in the public sector. Results confirm that telework positively influences both job satisfaction (β = 0.389, p < 0.001) and quality of work life (β = 0.323, p < 0.001). This evidence suggests that remote work, when adequately implemented, represents a sustainable practice for public organizations.

The study reveals that job satisfaction plays a fundamental role in how telework affects employees’ quality of work life (β = 0.425, p < 0.001). The findings indicate that satisfied employees in remote work arrangements generally experience enhanced overall life quality.

The research identified varying impacts among different groups. More experienced employees showed distinct responses to telework (β = −0.114, p = 0.017), indicating a potential need for differentiated support systems. Additionally, gender emerged as an influential factor in how telework affects job satisfaction (β = 0.275, p = 0.016), emphasizing the relevance of considering diverse needs in remote work policy development.

These findings suggest several practical implications for public institutions implementing telework:

Support systems require adaptation to employees’ experience levels.

Remote work policies should account for gender-related differences.

Organizations need to prioritize employee satisfaction maintenance.

Regular monitoring of telework effectiveness remains essential.

From a theoretical perspective, the study contributes to understanding sustainable work practices by demonstrating the interactions between telework, personal characteristics, and work outcomes. Future research could examine the longitudinal development of these effects and their variations across different organizational cultures.

The conclusions support the development of enhanced telework policies in public organizations, highlighting the necessity of considering individual differences in remote work implementation.