1. Introduction

Businesses strive for sustainability to compete in the global market. Sharing green knowledge can enhance employees’ green innovation capabilities [

1,

2] across sectors. Green knowledge sharing to disseminate and exchange environmentally friendly practices, technologies, and insights supports implementing sustainable solutions [

3]. Further, green knowledge sharing can be used to comply with global environmental regulations [

4]. In this regard, staying well informed about sustainability practices can anticipate future changes in environmental policy [

4]. By developing support networks, organizations can foster stakeholder trust and enhance market opportunities [

5]. The researchers and practitioners’ concern for sustainability has made examining the relationship between green knowledge sharing and employee green creativity in organizational settings crucial. An effective leadership style can determine organizational sustainability. Spiritual leadership and environmentally specific empowering leadership influence green knowledge sharing and enhance green creativity [

6]. Creative engagement affects employee creativity through problem identification, information searching, and idea generation [

7] via tacit and explicit knowledge sharing.

Enhancing employee green creativity is important for examining environmental performance and organizational competitiveness. Green creativity positively influences employees’ environmental performance [

8]. Adopting sustainable strategies for a protected environment and green human resource management practices can increase both green and general employee creativity and improve organizational innovation [

9]. Therefore, fostering green creativity among employees significantly drives organizations’ environmental sustainability.

Organizations that focus on environmental protection disseminate knowledge to induce sustainable practices among employees and prefer to adopt eco-friendly technologies [

10]. This knowledge-sharing creates a collaborative environment for creative solutions to environmental challenges [

1]. A positive impact of green knowledge sharing on green performance has been found earlier. However, how the impact of green knowledge sharing is translated into improved ecological performance still needs examination. The current study used a knowledge-based view [KBV] to highlight this missing link. A KBV considers knowledge an asset for organizations that want to gain a competitive advantage. This perspective can be applied to understand how sharing green knowledge leads to developing green creativity. Employees can drive creative and innovative sustainability solutions by sharing knowledge about green practices and technologies.

The human capital that enhances the translation of creative ideas into practical, innovative outcomes potentially benefits the environment. Green human capital has the environmental knowledge, skills, and competencies essential for the effective implementation of sustainable practices for sustainable innovations [

11]. Exploring the role of green human capital provides an understanding of how effectively an organization can actualize creative environmental solutions. Abbas and Khan [

1] argued that organizations with high levels of green human capital better create ideas to produce green products, services, or processes. This capability is critical because, while creativity generates ideas, human capital is required to implement these ideas successfully [

12].

Shahbaz et al. [

6] and Kozera-Kowalska [

13] suggested that human capital, particularly when focused on environmental aspects, can significantly influence the extent to which creative ideas lead to successful innovations. Moreover, green human capital enhances the ability of organizations to navigate the complex regulatory and technical landscapes associated with environmental innovations [

14]. Skilled employees understand not only the technological aspects but also the regulatory, social, and economic contexts in which green innovations must operate. A comprehensive understanding is crucial for adapting creative ideas to real-world applications that are innovative and compliant with environmental standards.

Saudi Arabia is increasingly embracing eco-friendly initiatives in alignment with its Vision 2030 strategy [

15]. This long-term national plan emphasizes the shift from an oil-dependent economy to a more sustainable, knowledge-driven one, which includes environmental and sustainability goals. Saudi Arabia’s eco-friendly organizational culture is evolving, driven by government policies encouraging corporate environmental responsibility and adopting sustainable practices [

16]. Organizations increasingly integrate sustainability into their business models and corporate social responsibility [CSR] frameworks. Many Saudi firms also emphasize green innovation, renewable energy, and efficient resource management to reduce environmental impact [

15,

16].

The knowledge-based view [KBV] of firms emphasizes that knowledge is the most critical resource in organizations, providing a sustainable competitive advantage [

17]. In the context of this study, green knowledge sharing aligns with a KBV by highlighting how the sharing and utilization of environmental knowledge within organizations can foster green creativity, improve environmental performance, and build a competitive edge. Green knowledge sharing is a key organizational process that leverages environmental knowledge to innovate and enhance sustainability performance. Similarly, green human capital is a vital component under a KBV, where employees’ environmental knowledge, skills, and expertise contribute to building organizations’ capabilities in sustainability.

The current investigation has four major aims. First, by using a knowledge-based view [KBV], a comprehensive model of how green knowledge sharing generates superior green performance is presented. Our study presents a holistic model integrating green knowledge sharing, creativity, human capital, and performance in a comprehensive framework. This integration of constructs offers a more nuanced understanding of how environmental performance can be enhanced through organizational and employee-level processes, making our study an important contribution to theoretical development and practical application in green management. Second, this study aims to investigate the role of green creativity as a mediator between green knowledge sharing and green performance. While previous research has separately examined the relationships between knowledge sharing and performance, our study is among the first to specifically explore how fostering green creativity can serve as a mechanism to achieve knowledge sharing. Third, the role of green human capital as a moderator for the green knowledge sharing and green creativity relationship is investigated. By integrating human capital with sustainability practices, we provide a novel perspective on how employees’ skills, knowledge, and environmental awareness can strengthen or weaken the impact of green creativity on environmental outcomes. This moderator role of green human capital has been underexplored in the literature, and our findings fill this gap. Lastly, we have tested the proposed moderated mediation model in an emerging economy, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Vision 2030 focuses on sustainability, bringing a unique context for generalizing knowledge developed and tested in developed countries and developing Asian economies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Knowledge Sharing and Green Performance

Sharing specialized knowledge about sustainable practices significantly enables organizations to innovate effectively by reducing the time and resources spent developing new green technologies or processes [

2]. At the same time, collaborative platforms and cross-sector partnerships significantly facilitate the transfer of knowledge, which is essential for fostering innovation for renewable energy, waste reduction, and so forth [

18]. Moreover, green knowledge sharing across organizations cultivates a culture of sustainability [

19], and by adopting it, organizations can gain competitive advantages [

20]. Song et al. [

3] argued that organizations actively engaged in green knowledge-sharing practices can likely achieve a higher green innovation performance. Such organizations leverage external knowledge sources and integrate them with internal R&D efforts to develop sustainable products [

18]. Employees engaged in sustainability initiatives show their commitment to their organization’s environmental goals. This benefits the organizational processes and publicly enhances the organization’s image and sustainability [

19].

Abbas and Khan [

1] found that green knowledge management, including knowledge sharing, remain a significant positive predictor of organizational green innovation and green performance. This strengthens employees’ green abilities. Shahzad et al. [

21] revealed that knowledge acquisition, dissemination, and application significantly lead to green innovation. Shafait and Huang [

10] examined green knowledge sharing and learning outcomes in 393 Chinese professionals. They found that these constructs had a significant positive relationship.

In light of the above arguments, this study posits that organizations with environmental knowledge exchange as a priority are better equipped to develop innovative solutions for sustainability. With the global emphasis on sustainability, the role of green knowledge sharing in driving innovation is likely to become more significant. The hypothesis developed is as follows:

H1: Green knowledge sharing has a positive relationship with green performance.

2.2. Green Knowledge Sharing and Green Creativity

Green creativity generates novel ideas contributing to environmental sustainability [

21]. It encourages waste reduction approaches, improves energy efficiency, and designs sustainable products [

22]. Access to diverse, eco-centric knowledge pools stimulates innovative thinking and problem-solving [

10]. Employees with access to a broad spectrum of environmental information and practices will likely devise unique solutions for sustainability challenges. Singh et al. [

14] found that environmental knowledge acquisition significantly enhances a firm’s capability to innovate with green solutions [

10].

Green knowledge sharing remains a healthy source of cross-disciplinary collaboration, providing foundations for green creativity [

23]. Professionals with different backgrounds collaborate and share their expertise to create comprehensive and creative environmental solutions [

24]. An organizational culture supporting knowledge sharing is integral in shaping green creativity. Organizations with learning environments and open knowledge exchange can likely encourage creative thinking among employees. Viale, Vacher, and Bessouat [

25] argued that organizations with strong internal communication and a commitment to sustainability initiatives can foster green creativity.

Furthermore, the digital platforms used by organizations at organizational and individual levels facilitate green knowledge sharing. Digital platforms allow the rapid dissemination of green knowledge across geographical and organizational boundaries, enhancing the scope for creativity [

26]. In light of the above arguments, it is assumed that organizations can significantly enhance their ability to generate creative, sustainable solutions by enabling access to diverse knowledge and fostering an environment conducive to collaboration. Therefore, the hypothesis developed is as follows:

H2: Green knowledge sharing has a positive relationship with green creativity.

2.3. Green Creativity and Green Performance

Green creativity is the ability to generate novel and valuable ideas that contribute to environmental sustainability. Exploring this relationship is becoming crucial, given the emphasized need for sustainability from businesses and governments globally. Malik, et al. [

20] examined green creativity as a critical antecedent of green innovation and found a significant relationship. Moreover, this creativity also enhanced the environmental performance of the studied organizations. Eco-friendly ideas are the first step toward developing practical, sustainable innovations that reduce ecological footprints [

27]. Green creativity fuels the invention of new products, services, and processes, fulfilling environmental goals. It further enhances an organization’s green innovation performance [

6].

Companies encouraging their employees to think green can cultivate a fertile environment for sustainable innovations [

24,

28]. Arici and Uysal [

23] argue that firms encouraging green creativity are likely to report enhanced green innovation outputs. This is particularly evident in industries such as automotive and manufacturing industries, where eco-friendly innovations can significantly impact a firm’s sustainability and economic performance. Moreover, developing digital tools and platforms that facilitate collaboration and idea generation [ideation] across boundaries fosters green creativity [

29]. These tools help harness the creative potential of individuals and teams globally, leading to diverse and innovative solutions to environmental problems.

Eco-friendly organizational strategies are crucial in fostering green creativity [

30]. Implementing policies integrating sustainability goals into the corporate mission and providing incentives for green innovation remain effective in enhancing green creativity and innovation performance [

18]. Overall, green creativity is not just about generating ideas that are environmentally sound but also about translating these ideas into viable solutions to enhance green innovation performance. With the dominance of environmental concerns as a global agenda, the synergy between green creativity and green innovation is in demand. The above arguments motivated the researchers to develop the following hypothesis:

H3: Green creativity has a positive relationship with Green Performance.

2.4. Green Creativity as a Mediator

Green knowledge sharing inculcates green creativity among employees across organizations. Knowledge sharing produces actionable, innovative practices that enhance sustainability [

19]. The interaction between these variables underscores a dynamic process in which knowledge dissemination leads to creative solutions, driving green innovation performance. The exchange of information through green knowledge sharing involves information about sustainable practices, technologies, and methodologies. Knowledge sharing about sustainability provides the groundwork for innovative thinking [

1]. This knowledge is utilized for green creativity. Utilizing this shared knowledge to generate novel and applicable ideas promotes environmental stewardship [

3].

Malik et al. [

31] and Bhatti et al. [

32] found that green creativity translates theoretical or shared knowledge into practical, innovative outcomes. An organization with a strong understanding of shared techniques may reduce waste in manufacturing. Employees might use this knowledge through green creativity to devise a new method or technology that minimizes waste more effectively, thus enhancing the organizational green innovation performance [

3,

32].

Ma et al. [

33] indicated that green knowledge sharing within organizations significantly boosts green creativity, positively impacting green innovation performance. Organizations encouraging risk-taking and experimentation enable employees to use their creative skills [

30,

34]. In this regard, leadership is crucial in setting a vision for sustainability and supporting innovative practices. Incorporating green creativity into the strategic processes of organizations can thus serve as a bridge that turns shared knowledge into competitive and sustainable innovations. Therefore, the hypothesis developed is as follows:

H4: Green creativity mediates the relationship between green knowledge sharing and green performance.

2.5. Green Human Capital as a Moderator

Green human capital combines employees’ skills, knowledge, and experiences relevant to environmental management and sustainable practices [

13]. It enhances organizations’ ability to effectively utilize and apply green knowledge and foster an environment that is conducive to generating creative, sustainable solutions [

12,

35]. Organizations with strengthened green human capital can generate and share green knowledge that boosts green creativity [

12]. This depends upon the absorption and application of shared knowledge, which is possible through green human capital. Employees with a higher understanding of environmental problems are better equipped to understand, assimilate, and apply environmental knowledge in innovative ways to solve problems [

1]. This capability strengthens green knowledge to generate viable, creative, eco-friendly solutions.

Jabbour et al. [

36] examined human capital as a moderator in environmental management and found that employees’ skills and competencies significantly influence the effective leverage of shared environmental knowledge for innovation. Organizations with robust green human capital can easily transform shared knowledge into green creativity and translate it into organizational, overall innovation and performance [

14,

37].

Furthermore, studies have examined the green human capital–green knowledge-sharing linkage [

6]. It is evident that various sectors look for employees with skills that help develop innovative products and processes [

3] for environmental protection.

Organizations that prefer to provide employee training to boost green human capital can amplify the benefits of green knowledge sharing [

31,

38]. Organizations that invest in continuous employee learning opportunities likely enhance employees’ environmental competencies to ensure creative green outcomes [

35,

39]. Integrating green human capital into strategic planning thus represents a crucial factor for organizations aiming to capitalize on green knowledge sharing for enhanced green creativity. Therefore, the current study posits that green human capital moderates the relationship between green knowledge sharing and green creativity by empowering employees to utilize shared environmental knowledge more effectively. The hypothesis developed is as follows:

H5: Green human capital moderates the relationship between green knowledge sharing and green creativity.

The proposed research framework is presented in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected using a survey questionnaire (see

Appendix A). The survey questionnaire was presented to the university review board and was approved by the board. The survey had two sections: the first asked for demographic information, and the second contained questions related to the variables present in the proposed model.

The data were collected from managers [lower and middle level] working in the telecommunication sector, the banking industry, restaurants, and government ministries that have offices in Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia. All these sectors play important roles in environmental conservation and contribute towards achieving the sustainability goals set in Saudi Vision 2020. We used snowball sampling, which is a non-probability sampling technique in which existing study participants help recruit further participants from among their acquaintances. This method is particularly useful for accessing hard-to-reach populations. Snowball sampling involves initial respondents who fit the study criteria and are asked to refer additional participants. As new participants refer others, the sample size “snowballs” and expands through social networks and contacts. The technique is iterative, with researchers gaining access to more participants until they reach a sample size that meets the study’s requirements [

40,

41].

The data were collected using Google Forms 2023 from employees working in various organizations with offices in Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, from the first week of August to the last week of November in 2023. Social media apps, including WhatsApp 2, were used as a major method of reaching the respondents. A total of 266 usable responses were received and used for hypothesis testing. The participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were ensured, and informed consent was obtained before gathering other information.

3.2. Survey Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section gathered demographic information about the respondents, while the second focused on the study variables. Scales for measuring these variables were adapted from the established literature. Green knowledge sharing was measured using five items adapted from Wong [

42]. Green creativity was assessed using eight items adapted from Zhou and George [

43]. Five items from Chen [

44] were used to measure green human capital, and six items from Zhu et al. [

45] assessed green performance [see the complete scale in

Appendix A].

3.3. Common Mothod Variance

Common method bias refers to the distortion in research findings that occurs when the data for both the independent and dependent variables are collected using the same method or from the same source, often leading to artificially inflated or deflated relationships among the variables. This bias is particularly relevant in survey-based studies where data are self-reported by the same respondents at the same time. To test that there were no issues of common method bias, we used Harman’s single-factor test [

46]. The result of Harman’s single-factor test revealed that the single factor accounted for 40.7% of the variance within the cutoff value of 50%. Hence, it was concluded that there was no issue of common method bias.

3.4. Demographic Analysis

A total of 266 usable samples were collected and used for data analysis. Ninety percent of the respondents were female, and the majority had 16 years of education. A total of 30% had 6–10 years of work experience, and 33% were from the age group of 31–35 years. The demographic information of the respondents is provided in

Table 1.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

In the first step of the analysis, the reliability and validity of the data set were assessed with the help of SPSS 20 and Amos 23. The Cronbach alpha values of all the latent variables in the proposed model were well above the cutoff value of 0.6 [

47]. Similarly, the composite reliability index supported the Cronbach alpha results and indicated that all the variables were reliable. The convergent validity was established for all the observed variables except GP6, as the rest of all the observed variables were successfully loaded into their respective constructs with factor loadings greater than 0.7. Due to the cross-loading and loading value of less than 0.7 for GP6, this item was not included in the further analysis. Lastly, the discriminant validity was ensured using the Fornell and Larcker criterion [

48], where the shared variance of each variable present in the model should be less than the AVE values of these variables. The results of the reliability and validity tests are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

To test the mediation impact of green creativity in the relationship between green knowledge sharing and green performance, we used Model 4 and the bootstrapping technique available in PROCESS macros for SPSS [

49]. This analytical technique helped in obtaining more robust results as PROCESS Macro uses a bootstrapping approach, which is recommended [

50] for the calculation of direct effects and indirect effects; as well as this, it calculates conditional indirect effects [indirect effects in the presence of moderators] with upper and lower bounds of 95% confidence intervals. We calculated the results of the simple mediation [direct effects and indirect effects] through 5000 subsamples with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. The mediation is confirmed when the indirect effects at a 95% CI do not include zero [

49]. The mediation analysis results in

Table 4 show that the total and direct effects of green knowledge sharing on green performance, [b = 0.8471;

p < 0.001] and [b = 0.4547;

p < 0.001], respectively, are significantly positive. Moreover, the indirect effect of green knowledge sharing via green creativity on green performance is also significant [b = 0.3127;

p < 0.001]. Lastly, the indirect effect’s 95% confidence limits [LLCI = 0.1510; ULCI = 0.523] also do not include a zero. Hence, the partial mediation effect of green creativity in the green knowledge sharing and green performance relationship is confirmed, supporting Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4.

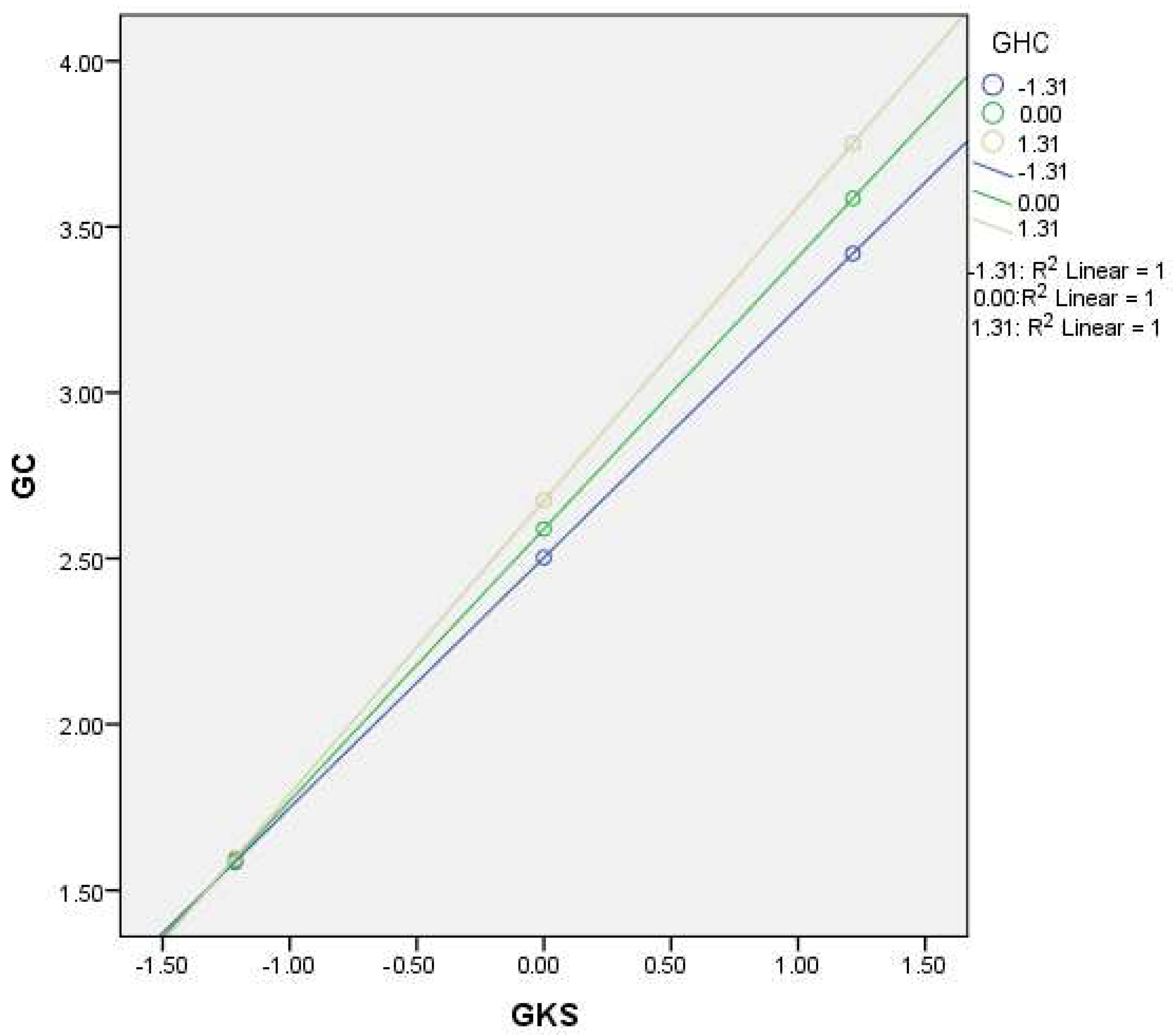

In the next step, we looked into the moderating role of green human capital. To test the hypothesis related to the moderating role of green human capital, we used Model 1 of Hayes’ PROCESS macro. To confirm the moderation, the significance of both the interaction and conditional effects are required [

49]. The interaction effect of green knowledge sharing and green human capital [GKS × GHC] is significant and positive [b = 0.050;

p < 0.05; LLCI = −0.001; ULCI = −0.099]. Additionally, the results of the overall moderation regression model are also significant [R2 = 0.720; ΔR2 = 0.01; F = 255.12;

p < 0.001]. See

Table 5.

To examine whether the indirect effect of green knowledge sharing on green innovation performance through green creativity is moderated by green human capital, we ran Model 7 [a moderated mediation model] from Hayes PROCESS macros [

22]. The results of the conditional indirect effects of green knowledge sharing on green innovative performance via green creativity at various levels of the green human capital [i.e., −1 SD, mean, and +1 SD] are presented in

Table 6 These results identify that the conditional indirect effects are significant at low [b = 0.278; LLCI = 0.126; ULCI = 0.521], medium [b = 0.303; LLCI = 0.147; ULCI = 0.525], and high values [b = 0.327; LLCI = 0.168; ULCI = 0.534], and the 95% CI does not show a zero. However, the indirect relationship between green knowledge sharing and green innovation performance via green creativity is stronger at higher values of green human capital than at lower values of green human capital, thereby confirming the presence of moderated mediation. The results of the conditional effect were also analyzed. However, the conditional effects values show that at high, medium, and low levels of green human capital, the positive relationship between green knowledge sharing and green human capital is enhanced [see

Table 6]. The graph in

Figure 2 also shows a significant positive relationship between green knowledge sharing and green creativity, which increases in the presence of green human capital, thus accepting Hypothesis 5.

5. Discussion

This study encompasses testing several hypotheses. Firstly, this study hypothesized that green knowledge sharing enhances green innovation performance. The results match with existing studies [

5,

19,

33]. Green knowledge sharing leads to developing problem-solving capabilities [

10]. The knowledge acquired enables individuals to look for ways to use the same procedures others use to address their environmental issues. The accumulation of diverse ideas and expertise leads to effective environmental solutions [

23].

Sharing knowledge offers several benefits, including the ability to fast-track innovation through strategic planning and the elimination of redundant efforts [

2]. Furthermore, sharing environmentally friendly solutions can also help optimize research and development expenditures [

12]. Interdepartmental collaboration is significantly enhanced through knowledge sharing, resulting in holistic approaches to sustainability [

18]. This culture of sharing also provides employees interested in green practices with valuable learning opportunities within their organizations [

1,

51]. A green knowledge-sharing culture drives innovation in environmental initiatives by encouraging employees to share their expertise and ideas [

14]. This collaborative environment promotes creativity and cultivates a shared commitment to sustainability.

Secondly, this study found a positive and significant impact of green knowledge sharing on green creativity. Green knowledge sharing facilitates the exchange of diverse perspectives and leads to environmental solutions. The shared knowledge increases employees’ problem-solving abilities and enhances green creativity [

52]. Moreover, it is noted that, by learning from one another’s experiences, people working together can implement sustainable methods that lead to creative ways to minimize waste and optimize resource usage [

20,

31]. Further, knowledge sharing promotes collaboration. Collaboration results in the pooling of ideas and resources that further lead to new green solutions [

6]. At the same time, regularly sharing green knowledge helps continuously improve processes and products [

29].

Thirdly, this study examined the relationship between green creativity and green performance and found a significant relationship. The results are supported by prior findings [

1,

3,

10,

53]. Green creativity leads to the development of innovative and environmentally friendly products for sustainability [

19]. Green creativity supports redesigning manufacturing processes and becoming waste-efficient for decreased energy consumption, which enhances overall innovation performance [

3]. Companies that harness green creativity often develop unique, eco-friendly products and processes that differentiate them from their competitors, which is simply not possible without showing environmental performance in the marketplace [

5,

20,

28,

54].

Fourthly, this study examined the mediation role of green creativity and found green creativity to be a significant mediator in the GKS and GP relationship. Green creativity is found to bridge green knowledge sharing and innovation performance by translating shared knowledge into innovative ideas [

1,

11,

24,

25]. Green creativity allows for the practical applications of the knowledge shared. Creative employees experiment with new things by testing their theoretical knowledge [

2,

5]. They turn theoretical knowledge into actionable, innovative projects and solutions that improve organizations’ environmental performance. Organizations can tackle environmental challenges very effectively by creatively using shared green knowledge [

10,

12,

20]. Moreover, employees engaged in green creativity are found to remain motivated to share knowledge and introduce diversified innovation processes. This further induces a higher commitment to developing innovative green solutions [

39,

52].

Lastly, the role of green human capital was examined as a moderator. The results identified GHC as a significant moderator. Employees’ skills and expertise in sustainability [green human capital] are enhanced through effective green knowledge sharing [

11,

13]. Such employees produce innovative green solutions by better understanding shared green knowledge [

12]. They generally deal with environmental issues and find alternatives to solve them, which means that their higher exposure to environmental issues leads to their higher chances of dealing with them effectively, therefore moderating the relationship between knowledge sharing and creativity [

6].

An organization possessing effective green human capital boosts the organization’s capacity for innovation. The knowledge and skills of employees in green practices better equip them to transform shared knowledge into actions, therefore enhancing the positive impact of green knowledge sharing on creativity [

6]. Further, experienced employees in green practices effectively assimilate new knowledge and adapt it creatively to develop innovative solutions, therefore adding to the green knowledge sharing and creativity link [

38]. The human capital that values sustainability engages in knowledge sharing and uses that knowledge creatively to enhance overall innovation outcomes [

13].

6. Practical and Theoretical Implications

Saudi Vision 2030 is a national strategic framework aimed at transforming Saudi Arabia’s economy by diversifying its income sources and reducing its dependence on oil [

55]. The environmental goals of Vision 2030 align closely with eco-friendly organizational practices. The key elements of Vision 2030 include the following: environmental sustainability, which focuses on specific goals to protect the environment by promoting the sustainable use of resources, reducing pollution, and encouraging environmental conservation; green economy, which focuses on transitioning to a green economy by promoting renewable energy projects and environmentally responsible economic growth; and energy efficiency, which aims to reduce energy consumption across all sectors, leading to organizational innovations that promote eco-friendly practices. Our study is aligned with the strategic goals of Saudi Vision 2030, which prioritizes environmental sustainability and the transition to a green economy. Vision 2030 promotes eco-friendly practices, renewable energy use, and energy efficiency [

56]. By investigating green knowledge sharing, creativity, and performance in Saudi organizations, our study contributes to understanding how organizational culture can support realizing these national goals.

By adopting a knowledge-based view [KBV], we emphasize the role of knowledge resources [green knowledge, expertise, and practices] in driving organizational innovation [green creativity] and enhancing eco-friendly performance. The KBV frames the central role of green knowledge sharing in the current investigation. The KBV posits that organizational knowledge, particularly environmental knowledge, is critical for driving competitive advantage [

17]. By sharing green knowledge, employees develop the necessary capabilities to innovate and enhance environmental performance, further contributing to sustainable organizational growth.

A KBV emphasizes that knowledge sharing within an organization builds core competencies. In the green context, sharing knowledge about sustainability practices and eco-friendly innovations fosters a culture of continuous improvement, which is crucial for maintaining environmental performance. By sharing environmental knowledge, organizations can adapt more quickly to evolving sustainability standards and regulatory requirements, positioning themselves as corporate responsibility leaders. This ability to adapt can provide a sustainable competitive advantage that is difficult for competitors to replicate.

A KBV highlights the importance of human capital [the skills, experience, and knowledge held by employees] as a unique asset. Green human capital development extends this view by focusing on the specialized knowledge and skills needed to drive environmental initiatives within organizations. Investing in green human capital, e.g., through green training and development programs, enriches an organization’s knowledge base, equipping it with the expertise required to innovate sustainably. This unique combination of green knowledge and capability strengthens the KBV framework, showing that organizations can enhance their competitiveness by cultivating environmentally oriented human capital.

Knowledge sharing nurtures creativity, and investments in human capital development ensure organizational, sustainable innovation. This enables organizations to enhance their capacity to innovate in ecologically responsible ways. The findings of this study remain valuable for practitioners and policymakers aiming to integrate green knowledge sharing, creativity, and human capital. The current investigation has several important implications. This study found a positive relationship between green knowledge sharing and innovation performance. This highlights the need to develop a culture of open knowledge exchange. The active exchange of green knowledge enhances organizations’ innovation capabilities, further leading to the development and adoption of sustainable processes. Organizations encouraging their employees to share green knowledge enable them to attain green creativity. This further encourages the dissemination of ecological knowledge within the organization to create a win–win situation for the employees and the organization. Promoting such practices generates a pool of creative and sustainability-focused ideas that remain helpful in developing innovative solutions to address environmental challenges. Therefore, organizations must focus on facilitating regular knowledge exchange through workshops, seminars, and collaborative projects to promote green innovation.

The finding that green creativity leads to green innovation performance is helpful for organizations aiming at cultivating creative employee thinking. Through their creative problem-solving training programs, organizations encourage sustainable green values. This will help organizations to nurture creativity for sustainability and ensure innovation. Creativity is a key mechanism that can connect knowledge sharing to innovation. Focusing on knowledge sharing and solving environmental problems keeps organizations creative for sustainability. Furthermore, having skilled and knowledgeable employees is a blessing for organizations. Investing in and developing green human capital enhances the effectiveness of knowledge sharing and creativity, thereby improving innovation potential.

Our research extends the green human resource management [GHRM] and sustainability management literature by providing empirical evidence on the interactions between green knowledge sharing, creativity, and human capital. Specifically, it contributes to the growing body of work on how organizations can leverage human capital to foster innovation and achieve better environmental performance. Additionally, by focusing on green creativity as a mediating factor, we offer fresh insights into the creativity literature, particularly in the context of sustainability. This opens up new avenues for further research on how creativity can drive sustainable innovation and performance. Finally, we provide actionable insights for practitioners by highlighting the importance of investing in green human capital and fostering an organizational culture that promotes knowledge-sharing and creativity to enhance sustainability outcomes.

7. Limitations and Future Directions

A few limitations are connected to this research study. Firstly, this study examined a single direct relationship between green knowledge sharing and green innovation performance. This can limit the understanding of the factors responsible for contributing to green innovation performance. There is potential to investigate the effects of financial freedom, green transformational leadership, employees’ green self-efficacy, and other factors that could contribute to green innovation performance. Such factors could offer deeper insights and practical recommendations for organizations to enhance their sustainable innovation efforts.

Secondly, this examination used self-reported questionnaires that are prone to biases such as the common method bias. It is recommended that future research studies use multiple sources of data to validate the findings. Further, this study captured data at a single point in time. This may limit our ability to understand the dynamic nature of the relationships. It is recommended to use longitudinal designs that track these variables over time to examine trends.

Thirdly, given that knowledge sharing, creativity, and performance can vary across industries, this study’s findings should be interpreted cautiously. Additionally, as the majority of respondents were female, this may limit the generalizability of the results. Future research should aim to include a more demographically diverse sample. Moreover, while this study focused on the years of work experience, future investigations could also consider the type and context of the work experience to provide more comprehensive insights.

Lastly, this study explored only a few mediators and moderators, specifically green creativity as a mediator and green human capital as a moderator. Other factors, such as green organizational culture, green procurement facilities, environmental dynamism, the role of technology, and so forth, are suggested to enrich the examined framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S., L.P. and M.I.M.; Methodology, F.S.; Software, F.S.; Formal analysis, F.S.; Investigation, F.S. and M.I.M.; Resources, L.P.; Data curation, F.S. and L.P.; Writing—original draft, M.I.M. and F.S.; Writing—review and editing, F.S. and L.P.; Supervision, F.S.; Project administration, M.I.M.; Funding acquisition, L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was received from the Institutional Review Board of Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support and for providing APC for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

Green Knowledge Sharing [

42]

I always share green knowledge obtained from newspapers, magazines, journals, television, and other sources.

I enjoy sharing environment-friendly knowledge with my colleagues

In my organization, people share expertise from work experience with each other.

Sharing my knowledge with colleagues is pleasurable

I believe that knowledge sharing can benefit all parties involved

I suggest new ways to achieve green goals or objectives

I come up with new and practical ideas to improve green performance

I search out new green technologies, processes, techniques, and/or green product ideas

I suggest new ways to increase quality by including green aspects

I consider myself as a good source of creative green ideas.

I promote and champion green ideas to others.

I always try to exhibit creativity on the job when given the opportunity to

I develop adequate plans and schedules for the implementation of new ideas related to environmental issues.

The contribution of environmental protection of employees in our firm is better than our major competitors.

Employee competence with respect to environmental protection in our firm is better than that of our major competitors.

The product and/or service qualities of environmental protection provided by the employees of this firm are better than our major competitors.

The amount of cooperative teamwork with respect to environmental protection in our firm is more than that of our major competitors.

Our managers fully support our employees in achieving their goals with respect to environmental protection.

Environmental performance [

45]

Our firm has reduced the air emission

Our firm has reduced the wastewater

Our firm has reduced the solid wastes

Our firm has decreased the consumption of hazardous/harmful/toxic materials.

Our firm has reduced/decreased the frequency of environmental accidents

Our firm has improved the company’s environmental situation

References

- Abbas, J.; Khan, S.M. Green knowledge management and organizational green culture: An interaction for organizational green innovation and green performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 1852–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L. Do knowledge sharing and big data analytics capabilities matter for green absorptive capacity and green entrepreneurship orientation? Implications for green innovation. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2024, 124, 978–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Yang, M.X.; Zeng, K.J.; Feng, W. Green knowledge sharing, stakeholder pressure, absorptive capacity, and green innovation: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1517–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketiah, E.; Song, H.; Adjei, M.; Obuobi, B.; Adu-Gyamfi, G. Assessing the influence of research and development, environmental policies, and green technology on ecological footprint for achieving environmental sustainability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Chen, Y.S. Determinants of green competitive advantage: The roles of green knowledge sharing, green dynamic capabilities, and green service innovation. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.H.; Ahmad, S.; Malik, S.A. Green intellectual capital heading towards green innovation and environmental performance: Assessing the moderating effect of green creativity in SMEs of Pakistan. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Cho, V.; Qi, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, F. Linking knowledge sharing and employee creativity: Decomposing knowledge mode and improving the measure of tacit knowledge sharing. In PACIS 2013 Proceedings; Association for Information Systems (AIS): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, M.; Il, B.; Park; Peng, M.Y.P. How does an employee’s green creativity influence environmental performance? Evidence from China. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2024, 94, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, J.R.; Singh, P.; Ezzedeen, S. Environmental Sustainability Strategy, Creativity, Innovation and Organizational Performance: The Role of Green Human Resource Management. Am. Bus. Rev. 2023, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafait, Z.; Huang, J. Examining the impact of sustainable leadership on green knowledge sharing and green learning: Understanding the roles of green innovation and green organisational performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 457, 142402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Ababneh, O.M. How can human capital promote innovative behaviour? exploring the attitudinal dynamics of employee engagement and mental involvement. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, S.; Yousaf, H.Q.; Ahmed, M.; Rehman, S. Effects of green human resource management on green innovation through green human capital, environmental knowledge, and managerial environmental concern. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera-Kowalska, M. Human capital for the green economy. Econ. Environ. 2024, 88, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhars, M.; Masoud, M.; AlNasser, A.; Alsubaie, M. Sustainable practices and firm competitiveness: An empirical analysis of the Saudi Arabian energy sector. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Salem, A.E.; Elsaied, M.A.; Elsaed, A.A. Determinants and consequences of green investment in the Saudi Arabian hotel industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A. Collaborative eco-innovation and green knowledge acquisition: The role of specific investments in Chinese new energy vehicle industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2245–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Saqib, A.; Abbasi, M.A.; Mikhaylov, A.; Pinter, G. Green Leadership, environmental knowledge Sharing, and sustainable performance in manufacturing Industry: Application from upper echelon theory. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103540. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.; Ali, M.; Latan, H.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Green project management practices, green knowledge acquisition and sustainable competitive advantage: Empirical evidence. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 2350–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U.; Islam, T. Exploring the influence of knowledge management process on corporate sustainable performance through green innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2079–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phrophayak, J.; Techarungruengsakul, R.; Khotdee, M.; Thuangchon, S.; Ngamsert, R.; Prasanchum, H.; Sivanpheng, O.; Kangrang, A. Enhancing Green University Practices through Effective Waste Management Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E.; Uysal, M. Leadership, green innovation, and green creativity: A systematic review. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 280–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, R.; Trio, O. Think green: The eco-innovative approach of a sustainable small enterprise. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 2792–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viale, L.; Vacher, S.; Bessouat, J. Eco-innovation in the upstream supply chain: Re-thinking the involvement of purchasing managers. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 27, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, M.Z.; Alsabban, A. Knowledge sharing through social media platforms in the silicon age. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qiu, H.; Xiao, H.; He, W.; Mou, J.; Siponen, M. Consumption behavior of eco-friendly products and applications of ICT innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, D.C.; Winston, A. Green to Gold: How Smart Companies Use Environmental Strategy to Innovate, Create Value, and Build Competitive Advantage; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K.P.; Mnisri, K.; Shrivastava, P.; Sroufe, R. Facilitating, envisioning and implementing sustainable development with creative approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejibe, I.; Okoye, C.C.; Nwankwo, E.E.; Nwankwo, T.C.; Scholastica, U.C. Eco-sustainable practices through strategic HRM: A review and framework for SMEs in the creative industries. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 042–049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y.; Cao, Y.; Mughal, Y.H.; Kundi, G.M.; Mughal, M.H.; Ramayah, T. Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Alyahya, M.; Alshiha, A.A.; Aldossary, M.; Juhari, A.S.; Saat, S.A.M. SME’s sustainability and success performance: The role of green management practices, technology innovation, human capital and value proposition. Int. J. Ebusiness Egovernment Stud. 2022, 14, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Ali, A.; Shahzad, M.; Khan, A. Factors of green innovation: The role of dynamic capabilities and knowledge sharing through green creativity. Kybernetes 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, K.; Kundi, Y.M.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Abualigah, A. Linking environmentally-specific empowering leadership to hotel employees’ green creativity: Understanding mechanisms and boundary conditions. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2023, 33, 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Alyahya, M.; Juhari, A.S.; Alshiha, A.A. Green HRM practices and employee satisfaction in the hotel industry of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Oper. Quant. Manag. 2022, 28, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Govindan, K.; Teixeira, A.A.; de Souza Freitas, W.R. Environmental management and operational performance in automotive companies in Brazil: The role of human resource management and lean manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: Methodological triangulation applied to companies in Brazil. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1049–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Abbas, Z.; Yousaf, M.; Zámečník, R.; Ahmed, J.; Saqib, S. The role of GHRM practices towards organizational commitment: A mediation analysis of green human capital. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1870798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafi, E.; Tehseen, S.; Haider, S.A. Impact of green training on environmental performance through mediating role of competencies and motivation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Flint, J. Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Soc. Res. Update 2001, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.S. Environmental requirements, knowledge sharing and green innovation: Empirical evidence from the electronics industry in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Geng, Y. Green supply chain management in China: Pressures, practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory—25 years ago and now. Educ. Res. 1975, 4, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Influence of perceived value on purchasing decisions of green products in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 110, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.S.; Ali, K.; Kausar, N.; Chaudhry, M.A. Enhancing environmental performance through green HRM and green innovation: Examining the mediating role of green creativity and moderating role of green shared vision. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2021, 15, 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. Green transformational leadership and green performance: The mediation effects of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6604–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y. Research on Sustainable Competitive Advantage Strategy of Leading Electric Vehicle Enterprises. Front. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 9, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M. Transformation from an oil-based economy to a knowledge-based economy in Saudi Arabia: The direction of Saudi vision 2030. J. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 8, 536–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Mohammed, I. Sustainability matters in national development visions—Evidence from Saudi Arabia’s Vision for 2030. Sustainability 2017, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).