1. Introduction

The proliferation of data, coupled with advances in information technologies, has drastically transformed the financial industry [

1]. Within the banking sector, innovative models of financing have emerged as new players—such as financial startups—have increased in numbers [

2]. Open Banking (hereafter OB) refers to the customer-permitted flow of data between financial institutions. Unlike traditional banks’ classic e-banking services, solutions enabled by OB agreements are typically offered by third-party providers (TPPs, hereafter) [

3]. This customer-approved data flow can transform users’ financial experiences and empower them to access, manage, and rearrange their finances more easily [

1]. According to a statistic published by Statista [

4], the value of OB transactions reached about USD 57 billion in 2023, and this figure is expected to increase by nearly 500 percent over the next few years, arriving at USD 330 billion in 2027.

Given the promising opportunities OB presents [

5], several countries have already established regulatory frameworks to encourage more participation [

3]. Saudi Arabia, through the efforts of its central bank Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) (Saudi Central Bank), has published detailed guidelines regulating OB implementation for both banks and TPPs. According to Babina et al. [

6], by October 2021, policies to promote OB adoption had been fully implemented in 49 countries, including, but not limited to, Ireland, Norway, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and all nations within the European Union. To date, SAMA has permitted eleven local FinTech startups to join the OB ecosystem through SAMA’s sandbox initiative [

7]. However, despite the substantial role users play in OB models’ success, our understanding of users’ experience with this innovative technology is still lacking [

8].

As Open Banking (OB) presents promising opportunities for financial innovation, several countries have already established regulatory frameworks to support its development and encourage broader adoption [

9]. For instance, the United Kingdom has been a pioneer in implementing OB, with the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) mandating the largest UK banks to adopt OB through the Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE) [

10]. Similarly, the European Union adopted the Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2), which requires banks to allow licensed third-party providers access to customer data with user consent [

11]. In Australia, the Consumer Data Right (CDR) legislation, which includes OB, empowers consumers to securely share their financial data [

12]. Other examples include Brazil, which launched its OB system through the Central Bank of Brazil, and South Korea, where the government introduced a regulatory framework to facilitate OB services by collaborating with the Korea Financial Telecommunications and Clearings Institute (KFTC).

These countries, alongside Saudi Arabia, are actively shaping the regulatory environment to support OB adoption and provide consumers with greater control over their financial data. By fostering innovation and competition in the financial sector, these frameworks are instrumental in driving the global growth of OB.

If implemented correctly, OB practices can transform the relationship between financial institutions and their customers [

13]. The financial service landscape will become more competitive as customers gain more control over their data [

8]. As a result, customer value will increase through personalization, transparency, and lower costs [

1]. In addition, financial inclusion will improve as access to financing applications becomes more tenable [

14]. Although the aforementioned studies on OB have contributed significantly to the body of literature, they have primarily studied adoption antecedents or customer experience. There is a lack of study regarding the sustained use of OB applications, which indicates a research gap in understanding users’ behavioral patterns.

However, despite the substantial role users play in OB models’ success, our understanding of users’ post-adoption behavior, particularly their long-term engagement with OB solutions, is still lacking. Existing literature primarily focuses on the factors influencing initial adoption, such as ease of use, perceived usefulness, and performance expectancy, leaving a gap in understanding what drives continuous use. Studies on post-adoption behavior, especially in the context of Open Banking, remain scarce. Moreover, the influence of variables such as trust and convenience on sustained user satisfaction and engagement has not been extensively explored, particularly in emerging markets like Saudi Arabia. This work extends the expectation-confirmation model of IS continuance use by exploring how trust and convenience impact the prolonged use of OB-enabled solutions in the Saudi context.

Although security concerns are commonly addressed in adoption studies, trust was selected as a more holistic measure because it encompasses both users’ perceptions of system security and provider credibility. Research has shown that trust plays a vital role in shaping technology adoption and post-adoption behavior, offering a broader lens through which to view user engagement. Additionally, convenience was chosen as a variable due to its direct impact on user satisfaction in digital services. In contrast to security concerns, which are often addressed during the adoption phase, convenience continues to influence user satisfaction and long-term engagement, making it a more relevant variable for investigating sustained use in the OB context.

Considering the paramount role of the financial sector in enabling the realization of Saudi Vision 2030 objectives [

15], understanding FinTech penetration in the Saudi context is increasingly important. Additionally, Saudi investors are expected to exhibit financial behaviors that are influenced by their distinctive circumstances (e.g., they tend to be risk-averse given the kingdom’s social climate [

16,

17]).

Saudi Vision 2030 is a strategic initiative aimed at diversifying Saudi Arabia’s economy and reducing its dependence on oil by enhancing public service sectors, including finance. Central to this vision is the digital transformation of the financial sector, particularly through the adoption of FinTech solutions like Open Banking (OB), which fosters a more inclusive financial ecosystem. Initiatives such as the Saudi Financial Sector Development Program (FSDP) promote financial inclusion, improve banking accessibility, and stimulate innovation through FinTech integration. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) supports OB implementation by creating a regulatory sandbox for FinTech firms to test new technologies. Vision 2030 also aims to enhance the ease of doing business to attract international investors, positioning Saudi Arabia as a regional hub for financial innovation. Ultimately, the alignment of Vision 2030 with the growth of the FinTech sector, including OB, reflects the kingdom’s goal of developing a modern financial system that meets the needs of a digitally savvy population, crucial for achieving economic diversification and sustainability.

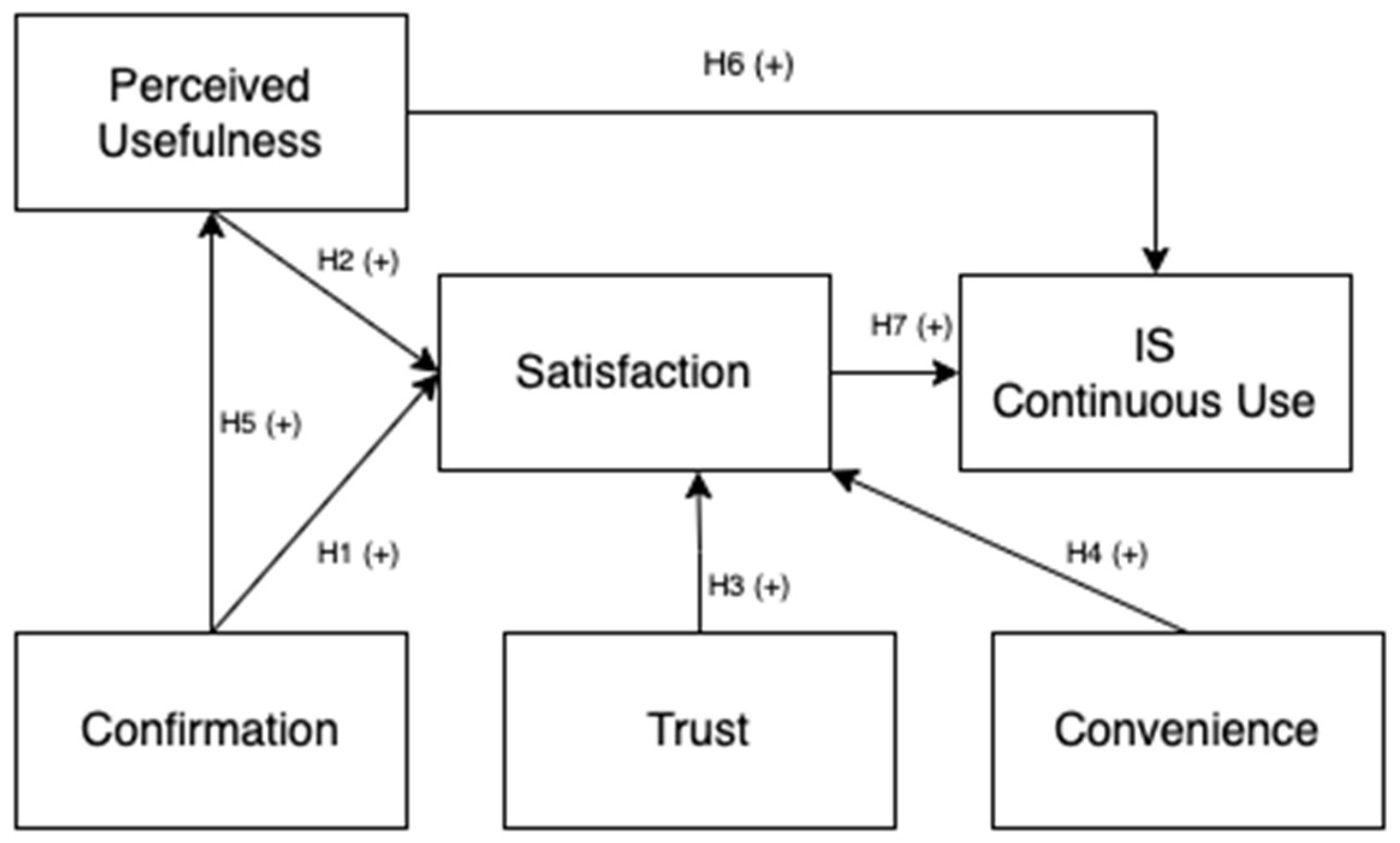

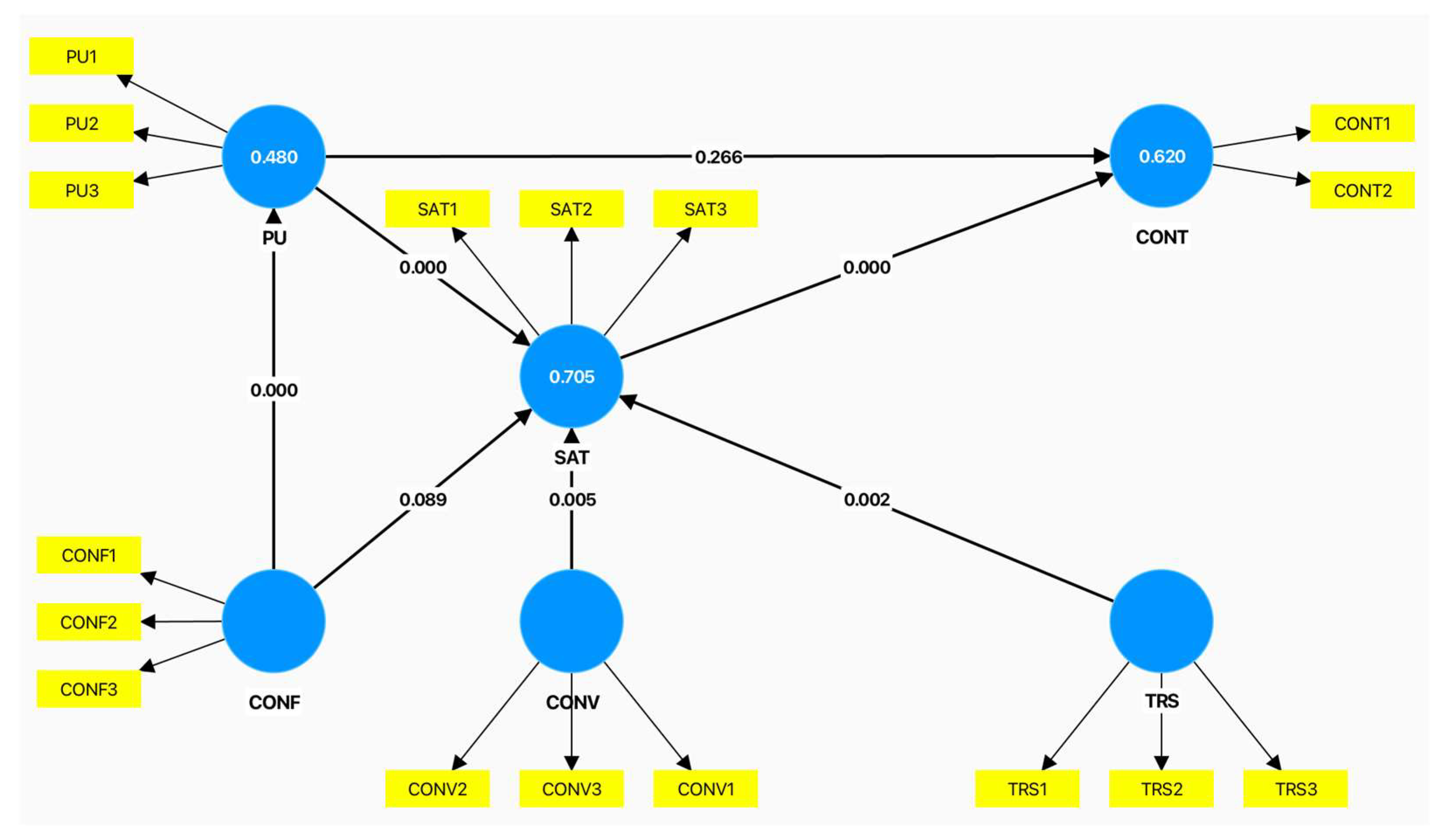

This study aims to address these research questions using the expectation-confirmation model of IS continuance use, extended with the variables of convenience and trust. The primary objectives of this research are to provide a brief overview of the innovative technology of OB, understand the current state of OB’s long-term use, and provide insights into successful long-term user engagement and potential barriers to sustained use practices. The novelty of this research lies in its efforts to examine the sustained use of OB applications. Most studies in this arena have been conceptual in nature, with a specific focus on regulatory frameworks. On the other hand, research analyzing the consumer viewpoint has mainly focused on the initial acceptance of OB technologies. To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the factors driving prolonged use of OB-enabled services. By focusing on the long-time usage of such services, the paper offers a unique perspective on the potential of OB to reshape the financial industry.

Motivated by the lack of research on this domain, our study seeks to investigate the following research questions:

RQ1—What are the determinants of users’ decision to continue using OB-enabled services?

RQ2—How do trust and convenience impact users’ satisfaction and, subsequently, continuance use intention?

The primary aim of this research is to explore the key determinants influencing the continuous use of Open Banking (OB) solutions in Saudi Arabia. As OB gains traction in the global financial ecosystem, understanding the post-adoption behaviors of users becomes crucial for ensuring sustained engagement with these services. This study specifically focuses on examining the roles of trust, convenience, and satisfaction in shaping users’ decisions to continue using OB solutions, with the intention of identifying actionable insights for OB providers and policymakers.

The key objectives of this research are as follows:

To analyze the impact of trust and convenience on user satisfaction with OB solutions;

To investigate the relationship between satisfaction and continuous use intentions in the OB context;

To assess the influence of perceived usefulness on post-adoption behavior, particularly in a cultural setting where risk aversion and trust concerns are prevalent;

To provide recommendations for OB providers on strategies to improve user engagement and retention in Saudi Arabia’s rapidly evolving financial landscape.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 explores the literature on the topic of OB.

Section 3 discusses the relevant theoretical background. In

Section 4, we develop our hypotheses and illustrate the research model.

Section 5 describes the process of collecting and analyzing the data. The results are reported in

Section 6.

Section 7 discusses the study’s findings and their implications.

Section 8 concludes this paper.

8. Conclusions

The aim of this paper is to study the impact of confirmation, perceived usefulness, trust, and convenience on satisfaction and continuous use intention for OB applications. Our results reveal a direct effect between confirmation, perceived usefulness, trust, and convenience on one hand, and satisfaction and continuous use of intention on the other. In contrast, our findings do not support the relationship between confirmation and satisfaction. While this study contributes to our understanding of FinTech’s continuous use, some limitations must be acknowledged. To improve user satisfaction and retention in Open Banking (OB) in Saudi Arabia, providers should focus on building trust through the clear communication of data privacy policies, transparent service agreements, and consistent service delivery. Enhancing convenience by offering intuitive interfaces, streamlined onboarding, and responsive customer support is also crucial. Since perceived usefulness was not a strong predictor of continuous use, providers should demonstrate the practical benefits of OB services through personalized insights, financial tools, and customized offers. These strategies, emphasizing trust, ease of use, and visible benefits, can also be applied to developing economies where Open Banking adoption is in its early stages, with strong regulatory frameworks helping to build user confidence and drive adoption.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The sample size of 98 respondents, while adequate for exploratory research, limits the generalizability of the findings; thus, larger and more diverse samples are needed for future research. While this study focused on trust and convenience, other factors like security concerns and regulatory impacts were not examined, necessitating their inclusion in future research for a more comprehensive understanding of Open Banking (OB) adoption. Lastly, the study’s context within Saudi Arabia may not be applicable to other regions, so comparative studies across different countries would provide valuable insights into global OB adoption trends. Addressing these limitations can enrich the understanding of OB adoption and support the global growth of the FinTech sector.