Abstract

In the agricultural sector, where factors like the type of agriculture, management techniques, and access to funding are critical, disadvantaged people face significant barriers to employment. This study investigated the effects of these factors, especially with regard to sustainability and social farming, on the employment of disadvantaged persons in the Czech Republic. We sent questionnaires to 2036 agricultural businesses within the Czech Republic, and the data we received were sorted and analyzed. There was a favorable relationship between farm size and employment chances. Disadvantaged people were more likely to be hired by large farms, especially those larger than 250 hectares. Furthermore, mixed-production farms were more capable of employing disadvantaged persons, unlike conventional farms, which reached their maximum employment levels at one, three, or six workers. Organic farming had a more even distribution, while biodynamic farming showed limited capacity to employ disadvantaged persons. Farms involved in fundraising had fewer farms but employed more disadvantaged persons (number of employees peaked at two, four, and six), while farms that did not engage in fundraising hired more disadvantaged individuals (peaked at one and three employees). The motivations for employing disadvantaged persons were primarily social concerns, as well as labor shortages and economic and innovative factors. These findings show the importance of agricultural enterprises using these factors to improve the social and economic well-being of disadvantaged persons.

1. Introduction

Social agriculture is a progressive method that builds relationships through networking, food cultivation, and supporting local well-being, breathing new life into urban and rural communities [1]. Social agriculture is an innovative approach that integrates agricultural activities with social services to benefit marginalized or disadvantaged individuals [2,3]. This practice merges the productive, therapeutic, and social functions of farming to provide opportunities for vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities, those recovering from mental health issues, the elderly, and individuals facing long-term unemployment. Social agriculture fosters an inclusive environment where disadvantaged people can engage in agricultural work, improve their mental and physical well-being, learn new skills, and feel included in society [4,5,6]. It is a strategy that expands services and agricultural output while providing answers to a range of community needs, including social, economic, and environmental concerns [7,8].

Social farming started in Europe in the 1970s, when small-scale farms began to provide therapeutic and rehabilitative services in countries such as Italy, the Netherlands, and Norway. Since then, the idea has grown to include a variety of models and forms based on local requirements and settings. Social agriculture is based on the idea that participation in agricultural work can provide therapeutic benefits [8,9]. For individuals with physical or mental disabilities, social farming can offer a sense of purpose, routine, and accomplishment. Farming, including animal husbandry, horticulture, or food production, has been shown to promote social interaction, lower anxiety, and increase self-esteem [10,11]. Depending on the program’s goals and, especially, the participants’ needs, social agriculture can take many different shapes; for instance, farms can work as rehabilitation facilities or as a component of mental health services with the help of qualified professionals [12,13]. Others believe that more emphasis should be on the long-term employment of disadvantaged people in agricultural settings by social businesses or cooperatives [14]. Social agriculture is closely related to the goals of sustainable agriculture because it promotes practices that are economically viable, socially responsible, and ecologically sound [15]. Social farming contributes to rural development by encouraging social inclusion and giving disadvantaged people employment opportunities. In order to further integrate sustainability into social farming frameworks, there is a need to focus on local food production, environmentally friendly farming practices, and biodiversity conservation.

In Europe, the development of social agriculture has been supported by public policies and initiatives that recognize the role of farming in delivering social services, particularly in rural areas. Programs like Italy’s “Agriculture for Social Inclusion” and the European Union’s rural development policies reflect a growing institutional commitment to social farming as part of a broader strategy to promote sustainable agriculture and social inclusion.

In the Czech Republic, the term “sociální zemědělství” corresponds to various English terms such as Social Agriculture, Green Care Farming, Farming for Health, Social Farming, and Farming Therapy [16]. This concept offers a way of reintegrating socially disadvantaged people into society [8]. By working in agriculture, these people can deal with their social or health problems [17].

Moreover, this approach provides an opportunity for farmers to diversify their income while creating conditions that facilitate the participation of disadvantaged individuals in typical farm tasks, thereby supporting their development and enhancing their physical and mental well-being [18].

Social agriculture has a wide range of target groups [19], including those experiencing difficulties in the labor market, as defined by Act No. 435/2004 Coll., on employment. However, its main emphasis is on individuals with physical, mental, emotional, sensory, or multiple disabilities, along with those facing the risk of social exclusion, as outlined in Act No. 106/2008 Coll., on social services.

Around 27 farms and therapeutic gardens in the Czech Republic are implementing the principles of social agriculture [16]. One notable example is Biostatek farm, which introduced the concept of social farming to the country through its involvement in the international project M.A.I.E. Other farm owners who are now considered social farmers were previously engaging in similar activities without recognizing them as part of the concept of social agriculture. They are now discovering the potential benefits of being classified under this category.

The employment challenges faced by disadvantaged individuals can be multifaceted and deeply entrenched [20]. Disadvantaged individuals often have limited access to quality education and training programs, which can hinder their ability to acquire the necessary skills for employment in today’s job market [21]. For disadvantaged people, discrimination on the basis of socioeconomic position, disability, gender, age, race, or ethnicity can significantly reduce their employment opportunities [22]. They might encounter discrimination at work or during the hiring process [23]. Many employments are acquired through personal relationships and networks. It is more difficult for disadvantaged people to find job opportunities since they lack these contacts [24]. This issue could be addressed through policy reforms, funding for education and training initiatives, anti-discrimination campaigns, and the development of supportive environments [25].

According to [26], social agriculture acts as a driver for employment and social equity by fostering the creation of new job opportunities in agriculture and related sectors. It provides employment opportunities, and sometimes accommodation, for vulnerable individuals, including those with mental or physical disabilities or those facing challenges in accessing traditional job markets [27,28]. Specifically, social agriculture trains these individuals to participate in the production and distribution processes, with a focus on groups that have lacked prior learning opportunities or have left formal education [26]. Participating in these activities allows individuals with specific needs to demonstrate their abilities, potentially leading to increased understanding and recognition of their capabilities by society [29]. Essentially, engaging in meaningful and valued occupations can bring significance and purpose to people’s lives, enabling them to develop and express their identities [30,31].

In the Czech Republic, individuals with health or social challenges can access protected employment [32]. Employers receive financial aid for these positions from the Labor Office, covering 75% of actual costs, including wages, social security contributions, state employment policy, and public health insurance. However, this assistance is granted solely to employers whose workforce comprises more than 50% of individuals facing health or social disadvantages.

Employment opportunities for disadvantaged individuals in agriculture can vary widely depending on factors such as farm size, type of production, management practices, technological advancements, and community engagement.

Larger farms with extensive land holdings and a higher number of employees may offer more employment opportunities simply due to their scale [33]. They may have openings for various roles such as farmhands, machinery operators, supervisors, and administrative staff. However, larger farms might also have higher competition for positions and potentially more stringent hiring criteria.

Conversely, smaller farms may have fewer job openings, but they could provide more personalized employment opportunities. They may be more likely to employ people with little education or experience, providing them with on-the-job training and opportunities for development within a smaller organizational structure.

The type of agricultural activities has a considerable influence on the job opportunities and skill sets needed [34]. Livestock farms may require individuals who are knowledgeable in animal husbandry, while plant-based farms may need individuals with skills in crop cultivation and harvesting.

Mixed farms could provide wider job opportunities since they require individuals with diverse skills to handle various areas of the farm.

Organic or biodynamic farms may offer employment opportunities for individuals with skills and experience in sustainable agriculture methods [35]. These farms might put more consideration on employing individuals who are knowledgeable in organic farming principles such as crop rotation, natural pest control, and soil health management. Conventional farms may not focus on a certain agricultural ideology but on a more traditional employment structure; however, they might still provide job opportunities for individuals with relevant skills and experience.

Inclusive and supportive workplaces could be achieved by modification of the working environment [36,37]. By eliminating attitudinal, physical, and technological barriers, these modifications encourage disadvantaged people to fully participate in agricultural jobs, adding their skills, abilities, and perspectives to the workforce.

Farms that involve the local community through activities like agritourism, educational programs, farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture (CSA), or fundraising initiatives may provide job opportunities beyond traditional farming roles [38]. These activities could create jobs in marketing, event coordination, customer service, and community outreach, providing opportunities for individuals with diverse skill sets.

Employment inclusion efforts in the agricultural sector should prioritize the unique strengths and abilities of disadvantaged individuals to create diverse and accessible job opportunities that leverage their potential. Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate how agriculture types, management regimes, public policies, and fundraising influence the employment opportunities, roles, and challenges faced by disadvantaged individuals in Czech agriculture.

To achieve this objective, the following research hypotheses were developed:

H1.

Mixed farms hire more disadvantaged individuals than sole farms

Mixed farming is the planting of crops and rearing of animals in the same portion of land. This system creates different tasks that can accommodate a range of skills from disadvantaged individuals.

In line with [39], diverse farms are more adaptable to the fluctuations in the labor market. Because of several workloads across the year, there is a flexible work arrangement in mixed farming. The work ranges from planting, maintenance, harvesting, and rearing of livestock. This flexibility can be a route to benefiting the disadvantaged person as it gives them an opportunity to engage in tasks that match their skills.

People with special needs can be integrated into companies offering different types of labor [40]. This might contribute towards better community relationships, build a socially welcoming environment, and reduce the unemployment of deprived workers [41].

H2.

Organic and biodynamic farms employ more disadvantaged individuals than conventional farms

This hypothesis assumes that organic and biodynamic farms employ more of the disadvantaged compared to traditional conventional farms due to their social and ethical principles. Organic and biodynamic farming exhibit a set of ethical criteria and lead to social inclusion and non-discriminatory policies of hiring for the recruitment of disadvantaged workers [42,43].

H3a.

Farms participating in external fundraising activities employ more disadvantaged workers

This hypothesis argues that farms in the active stages of fundraising are a superior opportunity for hiring poor/disadvantaged individuals due to increased funds to provide wages and training programs. Fundraising allows the farm to capture additional resources, which may be utilized to defray the additional costs of hiring poor/disadvantaged people. Such costs include wages, facilities, and benefits. Farms that enjoy higher financial freedom can invest more in their human resources. This provides a better chance for employment for the disadvantaged [44].

H3b.

Farms that acquire external finances are likely to employ more disadvantaged persons

This hypothesis states that those farms that raise funds externally would employ subsequently more disadvantaged people because of increased financial resources. It is also hypothesized that social inclusion may be successfully practiced by farms using external funding. External funds can be used to provide training and support services that facilitate the employment of disadvantaged people. Farms with additional financial resources are likely to include more employment-inclusive practices [45].

2. Methodology

A questionnaire was sent to the email addresses of 2036 agricultural enterprises in the Czech Republic. The first selection criterion was not being subscribed to the principles of a social enterprise. Other criteria included operating within the regions of the Czech Republic, documented economic activity in the previous year with proven turnover, classification under CZ-NACE, subsection 01 Crop and animal production, hunting, and related service activities. The enterprises had to employ at least one employee or be a self-employed individual (OSVČ) to ensure a minimum size and employment structure. The questionnaire was distributed electronically via email, enabling efficient outreach to many respondents while minimizing costs and logistical issues.

The sample of respondents included a wide range of agricultural enterprises, allowing for diverse and representative data collection on the use of the concept of social farming in the Czech Republic (CR). Under the CZ NACE, more than 110,000 business entities or self-employed individuals are registered in the CR. However, for this research, the decisive criteria were the availability of email contact, the type of agricultural activity (crop production, animal production, and mixed production), the size of the enterprise measured by both area in hectares and the number of employees (paid and unpaid), and the regional location of the enterprise, which were dispersed throughout the Czech Republic, ensuring regional representativeness. The questionnaire included various types of questions that allowed for the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. Closed questions enabled respondents to select answers from predefined options and provided structured information, such as yes/no questions and multiple-choice options. Open questions allowed respondents to write their own answers or comments, facilitating an in-depth analysis of their opinions and experiences. Scaling questions enabled the measurement of the intensity of respondents’ attitudes.

Only those respondents/farms that answered “YES” to the basic question “Does your company employ you/have you set up any jobs for the following people in the past?” were included in the analysis. This ensured the relevance of the analysis solely for enterprises that actually employ or have employed disadvantaged persons in the past. DATAtab: DATAtab Team (2024). DATAtab: Online Statistics Calculator. DATAtab e.U. Graz, Austria. URL https://datatab.net (accessed on 30 July 2024) was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results

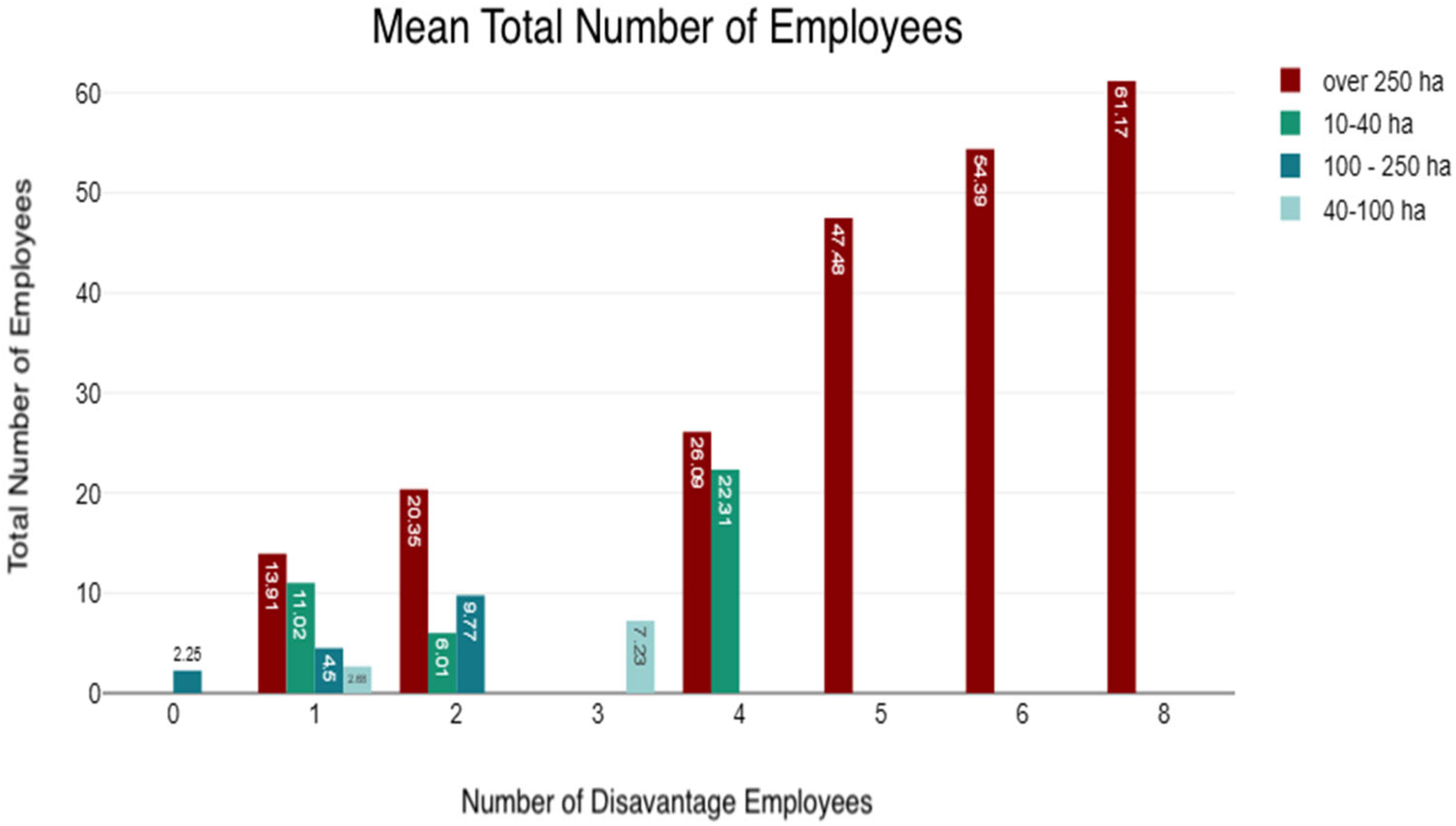

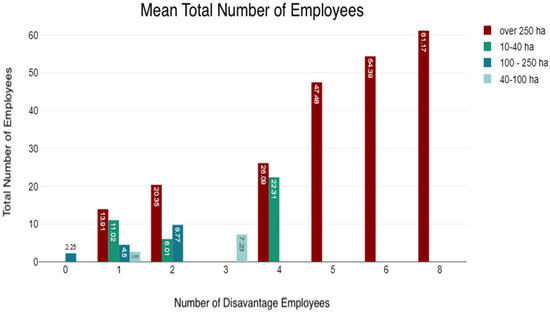

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the total number of employees on farms of different sizes based on the number of disadvantaged employees. The analysis aimed to identify trends and insights that can help explain how the inclusion of disadvantaged employees affects overall employment on farms.

Figure 1.

Mean total number of employees.

The farm sizes are categorized into four groups: 10–40 hectares (small farms), 40–100 hectares (small farms), 100–250 hectares (medium farms), and over 250 hectares (large farms).

The total number of employees in the surveyed enterprises generally increased with the number of disadvantaged employees, especially on farms larger than 250 hectares. Farms over 250 hectares in size employed the largest number of employees in all categories of disadvantaged employees. Farms smaller than 10 hectares are not represented in the data due to their low prevalence.

Small farms (10–40 hectares) employed a low total number of employees, irrespective of the number of disadvantaged employees. This suggests that smaller farms have limited capacity for both general and disadvantaged employment, reflecting their smaller operational scales.

Farms with 40–100 hectares had progressive growth in total employment, with up to four disadvantaged employees. This suggests that the workforce in these farms grows as they employ more disadvantaged individuals. However, this trend did not continue for larger numbers of employees. This might be due to capacity constraints.

Farms with 100–250 hectares followed a similar pattern, but there was a noticeable increase in the number of total employees when there were up to two disadvantaged employees. However, the tendency ceases beyond this threshold, suggesting more distributed operational capacity and employment of disadvantaged people. This could be attributed to poor resources and organizational capacity, which prevents the effective inclusion of disadvantaged persons.

The total number of employees in larger farms increased as the number of disadvantaged employees rose. For example, farms with eight disadvantaged employees had an average of 61.17 employees. This suggests that large farms can integrate disadvantaged individuals without compromising their operational efficiencies. This further indicates that large farms have the capacity to hire disadvantaged individuals and still maintain or increase their total workforce. This result highlights that farm size should be taken into consideration when developing support mechanisms and policies aimed at encouraging the employment of disadvantaged people in the agricultural sector.

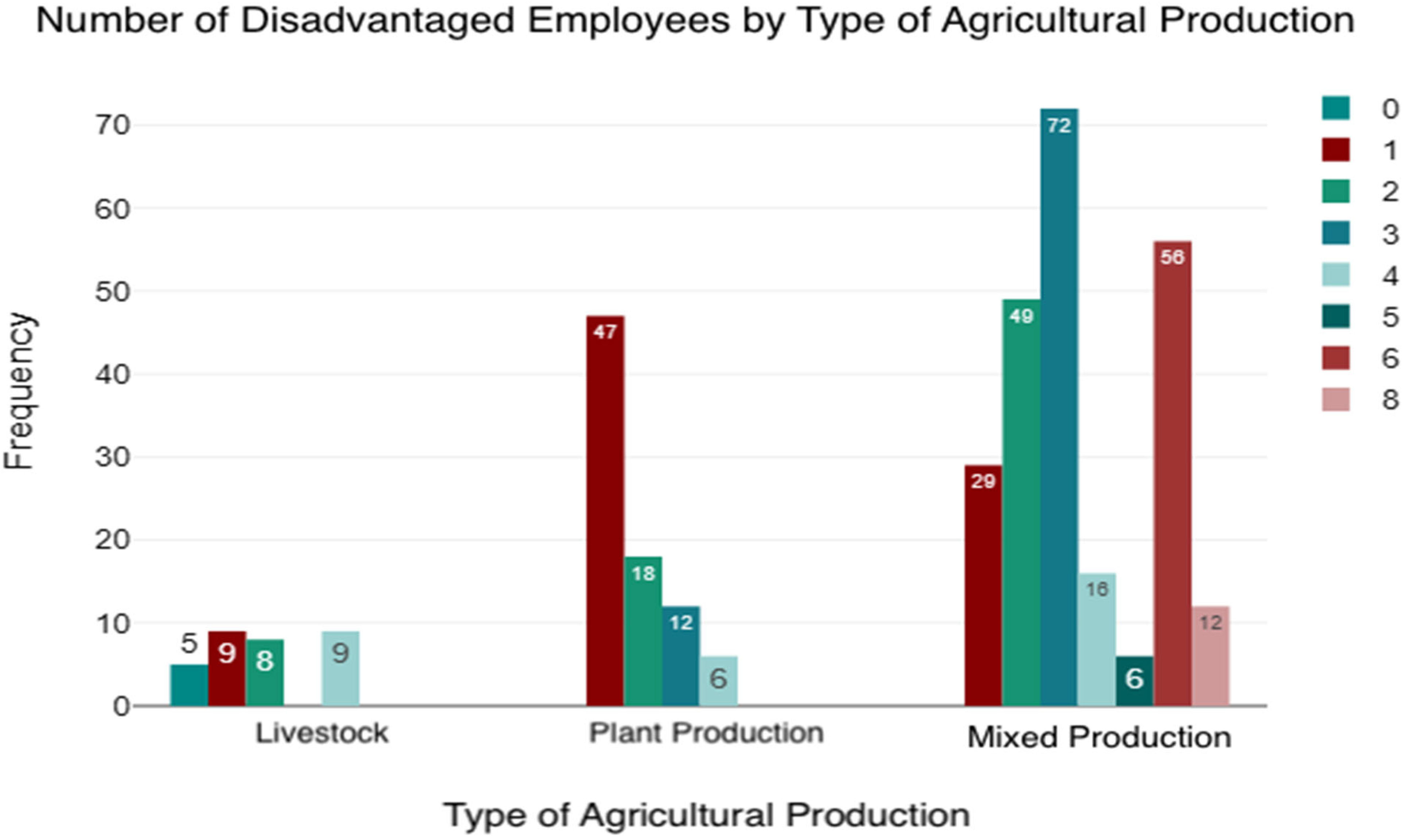

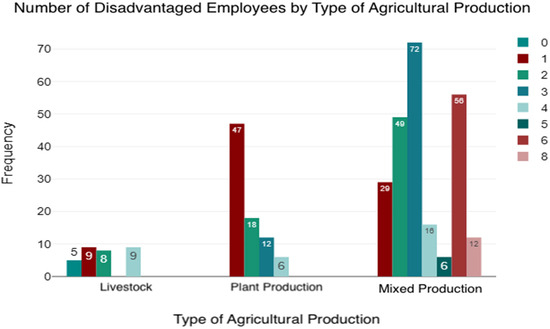

Figure 2 presents the distribution of employees across different types of agricultural production (livestock, plant production, mixed production) based on the number of disadvantaged employees in each type. Each column represents the frequency of disadvantaged employees in each type of agricultural production, with different sections of the column corresponding to the number of disadvantaged employees (1, 2, etc.).

Figure 2.

Number of disadvantaged employees by type of agricultural production.

In livestock production, there are 31 farms that employ disadvantaged individuals. Nine farms employed one disadvantaged employee, which is the second most frequent category. An equal number of farms (nine) also employed four disadvantaged employees. Eight farms employed two disadvantaged employees, representing a slight decrease compared to farms with one or four employees. Livestock groups have the fewest numbers of employees and a more limited range of disadvantaged employees.

The largest group consists of 47 farms that employ one disadvantaged employee, which is the highest frequency in this category. Additionally, 18 farms employ two disadvantaged employees, and 12 farms employ three disadvantaged employees. In total, there are 83 farms in plant production that employ disadvantaged individuals, indicating a higher capacity for employing them than in livestock production, though limitations still exist.

In mixed production, no farm is without disadvantaged employees, meaning that all farms in this category employ at least one disadvantaged employee. A significant portion, 29 farms, employs one disadvantaged employee, but a much larger number, 49 farms, employs two disadvantaged employees. The most frequent number of disadvantaged employees in mixed production is three, seen in 72 farms. Furthermore, 56 farms employ six disadvantaged employees, and 12 farms employ eight disadvantaged employees.

Mixed production has the highest overall number of farms with disadvantaged employees (240), indicating that this type of production employs significantly more disadvantaged individuals compared to livestock production (31) and plant production (83). There is a broader distribution across different categories, with notable peaks at three, six, and two employees per farm. This trend suggests that mixed farms tend to employ larger groups of disadvantaged employees more frequently, possibly due to the higher complexity and diversity of work on these farms.

The category with six disadvantaged employees shows a significant peak exclusively in mixed production, suggesting a unique aspect of mixed production that requires or supports such a group size. This may be due to the need for diverse skills and abilities on mixed farms, which combine elements of both animal and crop production.

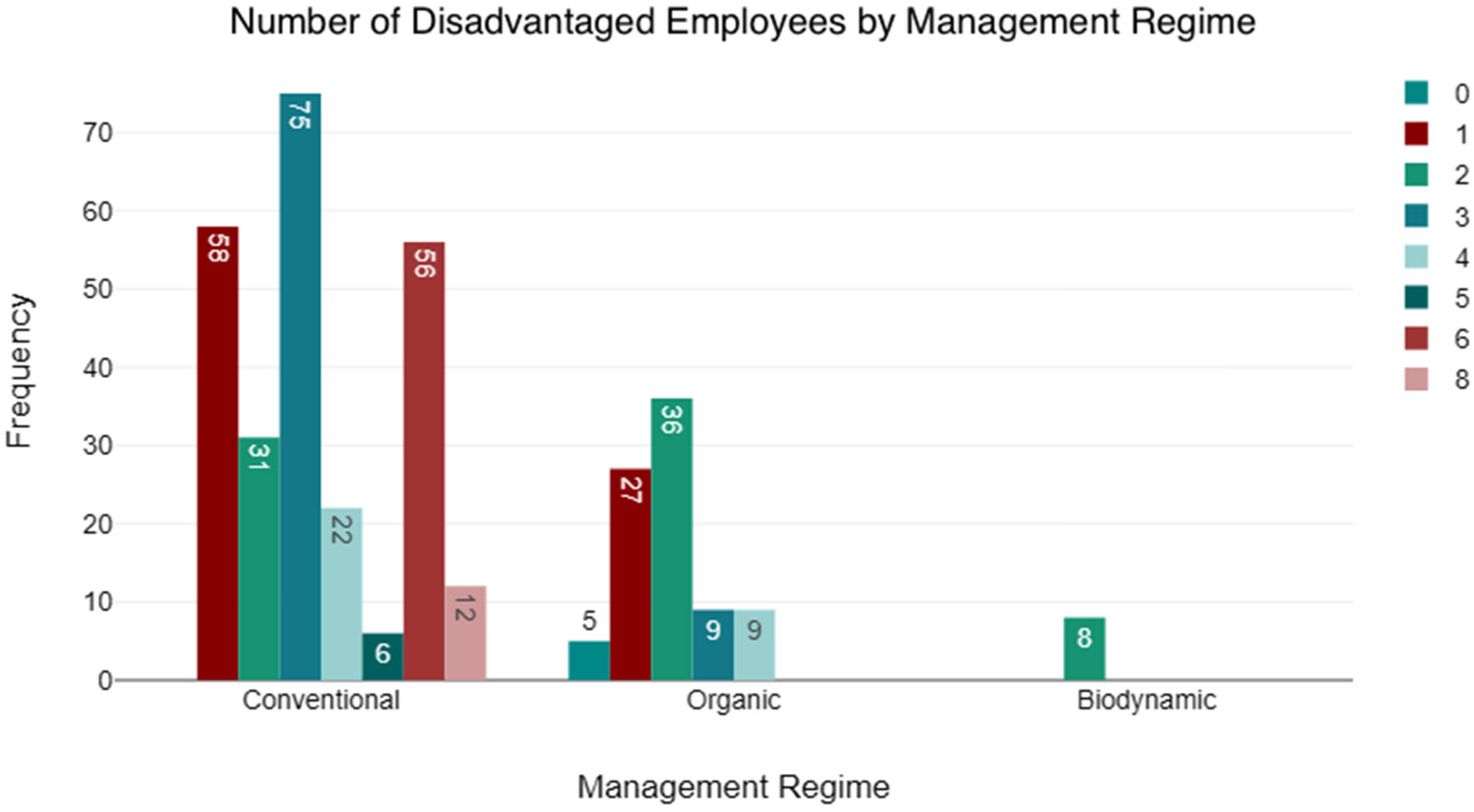

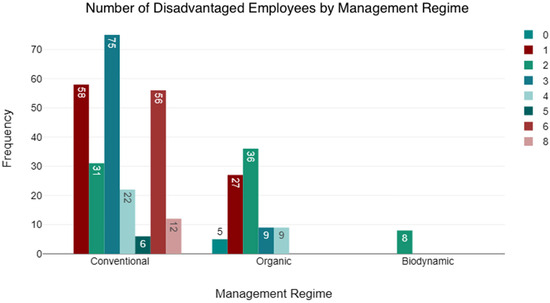

Figure 3 shows the distribution of employees across different management regimes, based on the number of disadvantaged employees in each regime.

Figure 3.

Number of disadvantaged employees by management regime.

The results show that conventional farming has the highest number of farms with all types of disadvantaged employees (260), meaning that this regime employs significantly more disadvantaged people than organic and biodynamic farming regimes combined (86 and 8, respectively).

For conventional farming, 58 farms hired one disadvantaged employee, while 75 farms hired three disadvantaged employees. It can be said that such farms have a big capacity to integrate more disadvantaged people. Fifty-six farms hired six disadvantaged employees. Altogether, 260 farms employed disadvantaged individuals in conventional farms. This points to the very important fact that conventional farming indeed employs the largest number of disadvantaged individuals compared with other agricultural regimes. The category with five disadvantaged employees shows a significant peak only in conventional farming, indicating a specific aspect of conventional farming that allows or enables such a group size.

Analysis of organic farming showed that 27 farms hired one disadvantaged employee, while 36 farms hired two employees, which is the highest frequency in this category. The categories for five, six, and eight employees are zero. In all, 86 farms hired disadvantaged employees in organic farming. This number indicates that organic farming has a limited capacity to employ people who are disadvantaged compared to the conventional farming sector, but provides a more even spread between the different categories with regard to the number of employees.

In biodynamic farms, apart from zero, the only represented category is two disadvantaged employees on eight farms; all other categories were not represented. Figure 3 shows that biodynamic farms have a limited capacity for employing disadvantaged people. On the other hand, all of the biodynamic farms that participated in the survey employed disadvantaged individuals.

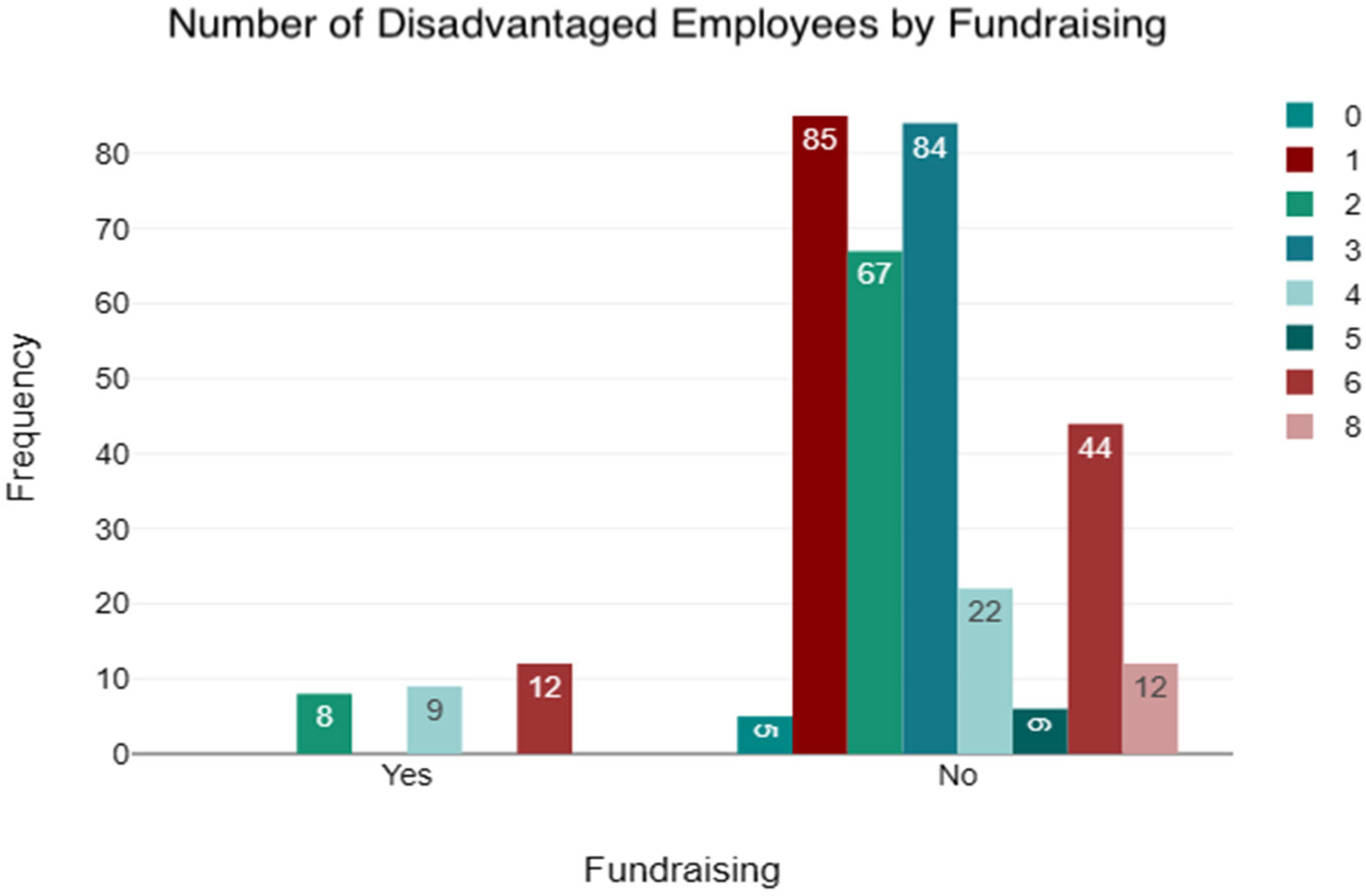

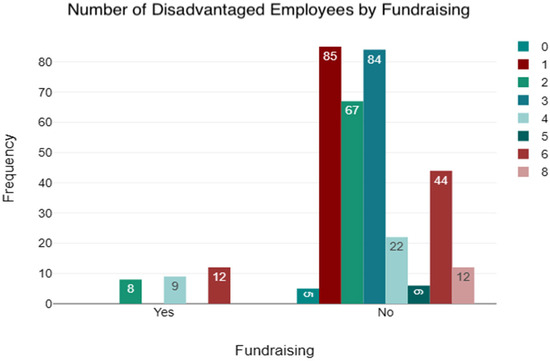

Figure 4 shows the distribution of disadvantaged employees across farms that engage in external fundraising. Fundraising in this scenario means seeking additional financial resources from external sources other than their own; this can be in the form of subsidies, support from the labor office, and applying for support grants or donations from philanthropists. The results show that most farms did not engage in fundraising but employed more disadvantaged individuals (325), while farms that engaged in fundraising employed 29 disadvantaged individuals. The frequency of disadvantaged employees in non-fundraising farms had one, two, or three employees per farm, with notable peaks at one and three employees. This indicates that these farms tend to integrate a smaller number of disadvantaged individuals. The frequency of farms that engaged in external fundraising had two, four, or six employees, with the highest peak at six employees. This indicates that farms that engage in fundraising have the capacity to integrate larger numbers of disadvantaged employees.

Figure 4.

Number of disadvantaged employees by fundraising.

In the category with six disadvantaged employees, there is a peak corresponding to farms that engage in fundraising, suggesting a unique aspect of these farms that supports such a group size. Interestingly, for farms involved in fundraising, there are no farms with zero, one, three, five, or eight disadvantaged employees, indicating specific trends or capacities related to these numbers of employees.

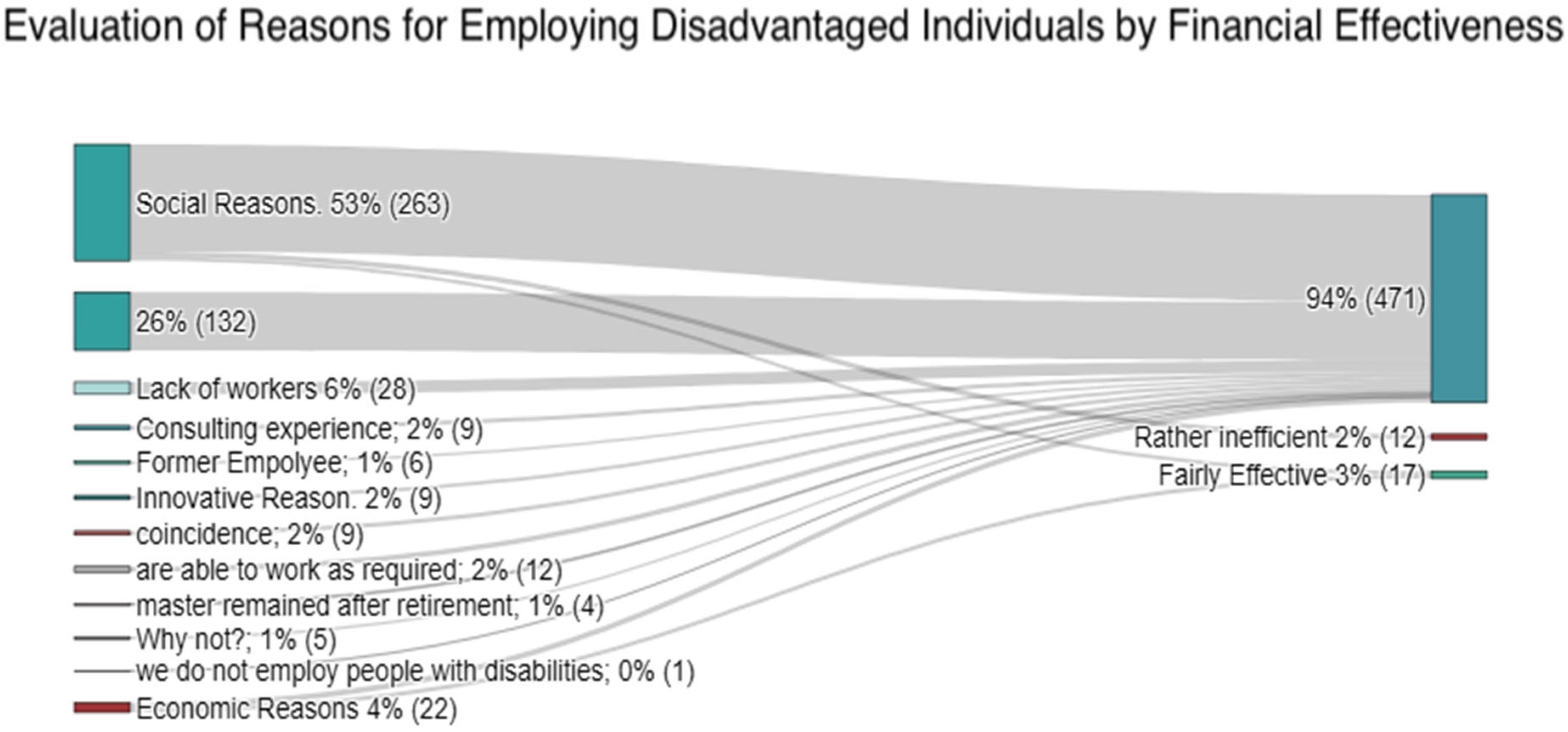

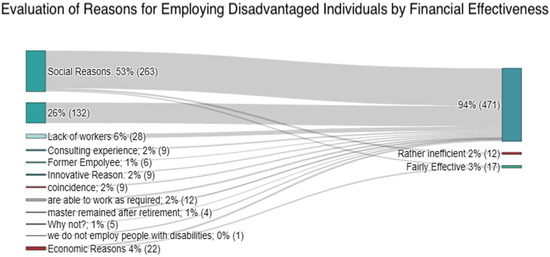

Figure 5 represents the frequencies of various reasons given when assessing the financial effectiveness of supporting the employment of disadvantaged individuals. Respondents answered the question, “What do you consider the main reasons for employing them?” They had several reasons to choose from and could scale their response from “Absolutely, yes” to “Absolutely not”.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of reasons for employing disadvantaged individuals based on financial effectiveness.

Analysis of individual reasons and associated employee numbers:

Social reasons (53%; 263 employees): This category reflects a commitment to social responsibility and inclusion, indicating an effort to provide opportunities for individuals who have faced challenges in their lives. In this category, 12 employees were considered rather ineffective and eight were deemed somewhat effective.

Economic reasons (4%; 22 employees): This category suggests that organizations view the employment of disadvantaged individuals as financially beneficial, potentially leading to higher productivity, reduced turnover costs, or access to government incentives. In this category, nine employees were considered rather ineffective, and nine were deemed somewhat effective.

Former employee (1%; six employees): This reason may stem from positive experiences with previously disadvantaged employees, leading organizations to continue supporting such individuals. In this category, one employee was considered rather ineffective, and five were deemed somewhat effective.

Consulting experience (2%; nine employees): Organizations seeking advice or consulting experience aim to gain insights into the benefits and best practices associated with employing disadvantaged individuals. In this category, six employees were considered rather ineffective, and three were deemed somewhat effective.

Shortage of workers (6%; 28 employees): Organizations facing difficulties attracting qualified workers may employ disadvantaged individuals as a solution to fill open positions. In this category, five employees were considered rather ineffective, and 23 were deemed somewhat effective.

Innovative reasons (2%; nine employees): With nine employees, this category emphasizes the potential of disadvantaged individuals to bring fresh perspectives and innovative ideas to the workplace. In this category, one employee was considered rather ineffective, and eight were deemed somewhat effective.

Coincidence (2%; nine employees): Some instances of employing disadvantaged individuals may occur by chance, without an intentional strategy, yet organizations still benefit. In this category, one employee was considered rather ineffective, and eight were deemed somewhat effective.

Employee remained after retirement (1%; four employees): This reason indicates a willingness to retain experienced individuals even after retirement, recognizing the value they bring to the organization. In this category, all employees were deemed somewhat effective.

Why not? (1%; five employees): This category may represent questioning the reasons for not employing disadvantaged individuals, indicating a proactive approach to overcoming prejudices and barriers. In this category, one employee was considered rather ineffective, and four were deemed somewhat effective.

They can meet job requirements (2%; 12 employees): Organizations believe that disadvantaged individuals can effectively meet job requirements, positively contributing to organizational goals. In this category, one employee was considered rather ineffective, and 11 were deemed somewhat effective.

4. Discussion

Social agriculture, also known as care farming, integrates agricultural production with social services, providing opportunities for disadvantaged individuals to engage in meaningful work [2,4,46,47,48]. This research examines the impact of selected factors on the employment of disadvantaged people in Czech agriculture.

According to the findings, farm size is an essential factor in the employment of disadvantaged individuals in the Czech agricultural sector. Larger farms (more than 250 hectares) have the capacity and resources to employ a greater number of disadvantaged individuals while maintaining or even boosting their entire workforce. Medium-sized farms can also help disadvantaged employees to some level, although their capacity is restricted when compared to larger farms. Small farms, with their limited resources, demonstrate a more limited potential to employ extra workers, including those from disadvantaged groups. This is in line with the research carried out by [49,50]. It should be noted, however, that there are also some social enterprises operating in agriculture. These enterprises are typically small (often employing between 15 and 20 employees), and their proportion of disadvantaged employees is significantly higher, generally at least 30% of the total workforce, and often comprising up to half or more of the employees. This form of enterprise was not included in the research, as this group of social enterprises operating in agriculture merits its own study and survey to separately investigate the phenomena explored in this questionnaire survey. Including them in the research could have significantly distorted the results and outcomes of this analysis.

Small farm owners are often poor and face numerous economic challenges, such as high labor costs, low income, and high crop inputs. Munćan Petar et al. [51] confirmed that as farm size increases, the utilization of available working time for permanent agricultural employees nearly doubles. The incomes of permanently employed workers in agricultural sectors tend to rise with the increase in farm size, suggesting the importance of considering farm size while making policies and support programs that encourage inclusive employment.

Targeted interventions and support mechanisms may be necessary to enable smaller and medium-sized farms to increase their capacity for employing disadvantaged people, thus fostering more inclusive employment practices across the agricultural sector in the Czech Republic.

The tendency for larger farms to employ more disadvantaged individuals than smaller farms can be attributed to a combination of factors. Large farms engage in organized management practices that can support the employment of disadvantaged workers. The disadvantaged workers may be employed in highly supervised sections or areas with less physical demand. Small farms lack this benefit because of the need for multi-skilled workers [52]. The operational arrangement of large farms encourages them to hire from underutilized labor pools, which can be supported by the government through subsidies or incentives to encourage the employment of disadvantaged individuals [53]. These factors suggest that larger farms are more concerned with social responsibility and employ more disadvantaged individuals, contributing to their significant role as employers in this sector. Mixed Production also supported the employment of disadvantaged workers across various categories. This suggests that mixed farming operations may offer more opportunities or be more adaptable in integrating disadvantaged workers. The diversity of tasks and broader operational scope in mixed production could provide a range of employment opportunities that accommodate varying skill levels and abilities. This aligned with [54,55], which stated that mixed production contributes to diversified livelihoods and resilience.

Livestock production has the lowest engagement with disadvantaged employees, with a notable absence of groups employing more than four disadvantaged individuals. This may reflect the specific skill sets and physical demands associated with livestock farming, which could present barriers to employing disadvantaged individuals. Working with livestock was perceived to be the most hazardous task, followed closely by the operation of tractors and machinery [35,56].

Plant production also has a significant number of groups employing disadvantaged individuals, particularly one or two disadvantaged employees. This might indicate that plant production offers roles that are accessible to disadvantaged individuals, possibly due to less physically demanding tasks or more flexible work arrangements.

The absence of groups with higher numbers of disadvantaged employees (five or more) in both livestock and plant production highlights potential barriers in these sectors. These barriers could include the physical nature of the work, specialized skill requirements, or possible economic constraints that limit the ability to support larger numbers of disadvantaged employees.

Given the concentration of disadvantaged employees in mixed production, support programs should consider the unique characteristics and opportunities within this sector. Tailored training and integration programs could enhance employment outcomes.

Identifying and addressing specific barriers in livestock and plant production is crucial. This may involve mechanization to reduce physical labor, targeted skill development programs, and economic incentives for farms to employ more disadvantaged individuals.

Sharing best practices from mixed production farms that successfully integrate disadvantaged employees can provide valuable insights for other sectors. These practices could be adapted and implemented to improve employment opportunities across all types of agricultural production.

The connection between different management regimes in agriculture (conventional, organic, and biodynamic) and the number of disadvantaged employees in each regime indicates that conventional management is the most common regime, accounting for 260 out of 354 farms. This regime has a wide distribution across all categories of disadvantaged employees, indicating its capacity to employ disadvantaged individuals in varying numbers. Although Refs. [43,57] proposed that organic farming may present opportunities for job creation over and above those provided by conventional agriculture, we could not find any studies in the literature specifically comparing the employment of disadvantaged people across management regimes.

Organic management, with 86 groups, shows a preference for employing one to four disadvantaged employees. This suggests that organic farms might be more adaptable or willing to integrate a moderate number of disadvantaged employees.

Biodynamic management is the least prevalent, with only eight groups, all of which have two disadvantaged employees. It follows that this farming regime creates suitable conditions for the employment of people with a handicap. This aspect could be explored in more depth and further investigation could focus only on biodynamic farms and investigate their conditions for the employment of these people.

Groups with higher numbers of disadvantaged employees (five or more) are found exclusively in conventional management. This suggests that conventional farms may have larger operations or more resources, enabling them to support a higher number of disadvantaged employees.

Given the higher concentration of disadvantaged employees in conventional management, targeted support and incentives could encourage organic and biodynamic farms to employ more disadvantaged individuals. This could include financial incentives, training programs, and infrastructure support.

Conventional farms might have more scalability and resources, allowing them to employ more disadvantaged workers. This is in line with the findings in [58], which stated that organic farming is characterized by lower yields and input use as well as higher output prices compared to conventional systems.

Policies could focus on enhancing the capacity of organic and biodynamic farms to reach similar scales, thus providing more employment opportunities.

Developing customized training programs for each management regime could address specific barriers and enhance the integration of disadvantaged employees. Customized training programs are specifically designed learning experiences that cater to the unique needs, goals, and objectives of an organization and its employees. It is necessary to educate employees on new digital, data-based, knowledge-based, and interoperable technologies [59]. For instance, organic farms might benefit from programs focusing on organic farming practices, while biodynamic farms might need support in implementing biodynamic principles efficiently.

The findings on the distribution of disadvantaged employees on farms based on their involvement in fundraising provide insightful contrasts between farms that seek additional financial resources and those that do not. Fundraising, in this context, refers to obtaining financial support from external sources such as labor offices, subsidies, and employment support grants.

Overview of Farm Involvement: The data show a clear distinction between farms that engage in fundraising and those that do not in terms of the total number of farms employing disadvantaged individuals. Most farms do not participate in fundraising, amounting to 325. This indicates that the majority of farms with disadvantaged employees do not rely on external financial support. In contrast, only 29 farms engage in fundraising and have a significantly lower number of disadvantaged employees.

Distribution of Disadvantaged Employees on Non-Fundraising Farms: For farms that do not engage in fundraising, the distribution of disadvantaged employees is primarily concentrated in the lower ranges, specifically one, two, and three employees per farm. Significant peaks are observed for one and three employees, suggesting that these farms tend to integrate a smaller number of disadvantaged workers. This pattern may indicate limitations in resources or capacities to support larger groups of disadvantaged employees without additional financial aid.

Distribution of Disadvantaged Employees on Fundraising Farms: Conversely, farms that do engage in fundraising display a different pattern in the distribution of disadvantaged employees. These farms exhibit frequencies of disadvantaged employees of two, four, and six employees per farm, with a notable peak at six employees. This distribution suggests that farms involved in fundraising possess the capacity to integrate larger groups of disadvantaged individuals. The peak at six employees is particularly significant, highlighting the unique capability of these farms to support a larger group size, likely due to the additional resources obtained through fundraising. Many authors emphasize the importance of fundraising, providing various reasons for its significance. They argue that fundraising fosters the development of social connections within the local community, spanning government, public administration, and commercial sectors. These connections form a foundation for establishing both corporate and individual fundraising efforts. Additionally, fundraising enables organizations to cover essential expenses with the funds they raise [60,61,62]. This is in line with the authors of [63,64,65], who stated in their studies that one emerging financing trend that has the ability to significantly broaden the base of the agriculture sector investment pyramid is fundraising.

Specific Trends and Capacities: An interesting observation is the absence of farms with zero, one, three, five, or eight disadvantaged employees among those engaged in fundraising. This absence points to specific trends or capacities associated with these farms. The lack of farms with only one disadvantaged employee might indicate that farms involved in fundraising prefer to integrate more substantial groups, leveraging the additional resources to create more impactful employment opportunities. This aligns with [66], which mentioned that fundraising efforts enabled small-scale and emerging farmers to increase their crop production and expand their workforce. Similarly, the absence of farms with three, five, or eight employees could reflect strategic decisions in the distribution and management of the workforce, optimized for the resources available through fundraising efforts.

Implications: The findings underscore the importance of fundraising in enhancing the capacity of farms to employ disadvantaged individuals. Farms that do not engage in fundraising show a tendency to hire fewer disadvantaged employees, potentially due to resource constraints. In contrast, farms that obtain external financial support can support larger groups, indicating that fundraising plays a critical role in enabling these farms to provide more extensive employment opportunities for disadvantaged individuals.

The distribution patterns of disadvantaged employees on farms reveal significant differences based on their involvement in fundraising. Non-fundraising farms typically integrate fewer disadvantaged employees, while fundraising farms can support larger groups, peaking at six employees. These patterns suggest that additional financial resources are crucial in enhancing the capacity for employment of disadvantaged individuals on farms. Future research could explore the specific mechanisms through which fundraising influences employment capacities and the long-term impacts on both farms and disadvantaged employees.

The analysis of respondents’ reasons for employing disadvantaged individuals reveals a multifaceted approach to integrating these employees into the workforce. By examining the different categories of reasons and their perceived effectiveness, we can gain insights into the motivations and outcomes of employing disadvantaged workers.

Social Reasons: Employing disadvantaged individuals for social reasons is the most cited category (cited by 263 employees). This aligns with [67,68], which noted that the primary motivations for employing disadvantaged individuals in social agriculture were centered around social inclusion. This reflects a strong commitment to social responsibility and inclusion, highlighting an effort to provide opportunities for individuals who have faced challenges. However, the effectiveness is mixed: 12 employees were considered rather ineffective, while eight were deemed somewhat effective. This suggests that while the social motivation is strong, the practical outcomes may vary, potentially due to the need for better support systems or integration strategies.

Economic Reasons: The second most common reason is economic, with 22 employees. Organizations view employing disadvantaged individuals as financially beneficial, possibly due to higher productivity, reduced turnover costs, or access to government incentives. Similar to social reasons, the effectiveness is split evenly, with nine employees considered rather ineffective and nine somewhat effective. This indicates that while economic incentives are significant, the realization of these benefits may depend on how well the employees are integrated and supported. This aligns with [69], which stated that, beyond moral arguments and legal obligations, economic reasons also support the hiring of disabled employees.

Former Employees: Employing former employees accounts for six individuals. This reason likely stems from positive past experiences, leading to continued support for such workers. The effectiveness here is notably higher, with five employees considered somewhat effective and only one rather ineffective. This suggests that familiarity and past success can be strong predictors of future performance for disadvantaged employees. This aligns with [70], which noted that past performance is a reliable indicator of future potential.

Consulting Experience: Nine employees are hired due to the influence of consulting experience. Organizations seeking advice on best practices for employing disadvantaged individuals may benefit from this approach. However, the results are less favorable, with six employees considered rather ineffective and three somewhat effective. This indicates that while consulting can provide valuable insights, the actual implementation may face challenges.

Shortage of Workers: Addressing the shortage of workers is a reason cited for employing 28 disadvantaged individuals. In this category, five employees were considered rather ineffective, and 23 were deemed somewhat effective, suggesting that employing disadvantaged workers can be an effective solution to meeting immediate labor needs. This supports [71], which stated that employing disabled individuals can help alleviate the worker shortage in the labor market.

Innovative Reasons: Nine employees were hired for their potential to bring innovation. In this category, one employee was considered rather ineffective, and eight were deemed somewhat effective, highlighting the value of diverse perspectives and new ideas that disadvantaged individuals can contribute to the workplace. This supports [72], which noted that individuals with disabilities actively participate in product development, and their contributions positively impact their own lives.

Coincidence: Employing disadvantaged individuals by chance accounts for nine employees. Despite the lack of intentional strategy, the outcomes are generally positive, with eight employees deemed somewhat effective and only one rather ineffective. This suggests that even unplanned hiring can result in beneficial outcomes for the organization.

Employee Remained After Retirement: Four employees were retained after retirement, reflecting a recognition of their value and experience. All employees in this category were considered somewhat effective, indicating that retaining experienced workers can be beneficial for the organization. This supports [73], which mentioned that retaining employees enhances organizational performance and outcomes.

“Why Not?” Approach: This category was incorporated as a proactive approach to overcome biases from the respondents, where five employees were employed under the reason “why not?”. Four employees were considered somewhat effective and only one was rather ineffective.

Meeting Job Requirements: Twelve employees were hired because they met the job requirements of the organization. Eleven employees were somewhat effective and only one was rather ineffective. This suggests that disadvantaged individuals perform well when they are perceived to meet job requirements. This study reveals that the reasons for employing disadvantaged individuals are many, with differing levels of perceived effectiveness. The most frequent drivers are social, shortage of labor, and economic motives. Segments such as ex-employees, shortage of labor, innovative reasons, and fulfillment of job requirements prove to be more effective in certain contexts in order to show contexts where the disadvantaged worker can be of use to the workforce. This proves that, in fact, inclusion strategies count and the staff facing disadvantages are able to bring along added value. Further research will help give a better understanding of exactly which elements make the employment of disadvantaged workers even more effective, resulting in a long-lasting positive impact on the employees and organizations alike.

Opportunities for Further Research

Future research should focus on identifying specific factors that affect smaller farms’ ability to employ disadvantaged individuals. This entails examining the abilities, infrastructural requirements, and training necessary for this set of workers to integrate successfully. Studies have shown that different types of farmers need different adaptation and development options [74,75]. It would also be helpful to investigate how fundraising and other financial assistance may help to improve the employment of disadvantaged individuals in agriculture.

5. Recommendations

Smaller farms (10–100 hectares) have the potential to employ disadvantaged individuals but often lack resources [49,50]. Targeted interventions could be developed in the form of financial assistance, training programs, and infrastructure development that can help them expand their workforce by integrating disadvantaged employees.

Mixed production systems should be strengthened through technical support and professional training. This could increase their ability to hire disadvantaged individuals. Various skills can be accommodated in mixed production because of their diversity of tasks, making it an ideal sector for integrating disadvantaged employees [54].

Strategies that support organic and biodynamic farms in employing disadvantaged individuals should be implemented. This can be in the form of training programs and financial incentives.

Lastly, external fundraising should be encouraged among farms since this can improve their capacity to hire a greater number of disadvantaged individuals [60].

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the factors influencing the employment of disadvantaged individuals in the Czech Agricultural sector with the aim of informing disadvantaged employment inclusion policies. While smaller farms (10–40 and 40–100 hectares) have resource limitations that restrict their capacity to employ disadvantaged individuals, larger farms, those larger than 250 hectares, have a good chance of employing disadvantaged individuals.

The greatest ability to employ disadvantaged individuals is seen for mixed production farms, which exhibit notable peaks of two, three, and six employees per farm, suggesting more flexibility and integration options. Conventional farming employs the most disadvantaged individuals, while organic farming employs fewer disadvantaged individuals but provides a more equitable distribution. The potential of biodynamic farming is extremely limited in this regard.

Farms not engaged in fundraising exhibit higher overall capacity to employ disadvantaged individuals, while those that do engage in fundraising can integrate larger groups, with peaks at two, four, and six employees.

The most prevalent and effective reasons for employing disadvantaged individuals were social reasons, shortage of workers, addressing economic factors, and leveraging innovative potential.

Finally, to enhance the employment of disadvantaged individuals in Czech agriculture, organizations should develop a strategy to support small farms, promote mixed production, and encourage external fundraising.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.O.E. and T.C.; methodology, T.C. and J.M.; software, A.M., F.O.E. and C.E.M.; validation, F.O.E., J.M., P.B. and T.C.; formal analysis, F.O.E. and A.M.; investigation, T.C., F.O.E., A.M., J.M., C.E.M. and P.B.; resources, P.B.; data curation, F.O.E., A.M., O.G.E. and C.E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., F.O.E., A.M. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, T.C., F.O.E. and O.G.E.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, P.B., J.M. and T.C.; project administration, P.B., J.M. and T.C.; funding acquisition, P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Uliano, A.; Stanco, M.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Evaluating citizen-consumers’ attitude toward high social content products: The case of social farming. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 4038–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genova, A.; Maccaroni, M.; Viganò, E. Social Farming: Heterogeneity in Social and Agricultural Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, C.D.; Ravazzoli, E.; Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M.; Polman, N.; Melnykovych, M.; Pisani, E.; Gori, F.; Da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Secco, L. The Role of Agency in the Emergence and Development of Social Innovations in Rural Areas. Analysis of Two Cases of Social Farming in Italy and The Netherlands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moruzzo, R.; Di Iacovo, F.; Funghi, A.; Scarpellini, P.; Diaz, S.E.; Riccioli, F. Social Farming: An Inclusive Environment Conducive to Participant Personal Growth. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Laganà, V.R.; Di Gregorio, D.; Privitera, D. Social Farming in the Virtuous System of the Circular Economy. An Exploratory Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iacovo, F.P.; O’Connor, D. Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe: Progressing Multifunctionality in Respojnsaive Rural Areas. 2009. Available online: https://www.umb.no/statisk/greencare/sofarbookpart1.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Sustainable Collective Innovation in the Agri-Food Value Chain: The Case of the “Aureo” Wheat Supply Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F. Social agriculture is a strategy to prevent the phenomenon of abandonment in mountain areas and areas at risk of desertification. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Llorente, M.; Rubio-Olivar, R.; Gutierrez-Briceño, I. Farming for Life Quality and Sustainability: A Literature Review of Green Care Research Trends in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgi, M.; Collacchi, B.; Correale, C.; Marcolin, M.; Tomasin, P.; Grizzo, A.; Orlich, R.; Cirulli, F. Social farming as an innovative approach to promote mental health, social inclusion and community engagement. Ann. Ist. Super Sanita 2020, 56, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, R.; Barton, J.; Pretty, J. Care Farming in the UK: Contexts, Benefits and Links with Therapeutic Communities. Ther. Communities 2008, 29, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Hlušičková, T.; Gardiánová, I. Farming therapy for therapeutic purposes. Kontakt 2014, 16, e51–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Lamont, K.; Wendelboe-Nelson, C.; Williams, C.; Stark, C.; van Woerden, H.C.; Maxwell, M. Engaging the agricultural community in the development of mental health interventions: A qualitative research study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassink, J.; Hulsink, W.; Grin, J. Care Farms in the Netherlands: An Underexplored Example of Multifunctional Agriculture—Toward an Empirically Grounded, Organization-Theory-Based Typology. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 569–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrette, C.; Du, J.; Diakité, D. Sustainable agricultural practices adoption. Agriculture 2021, 67, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromadova, M.; Hanusova, H.; Stastna, M. Perception Social Farming in Czech Republic and Great Britain. 2017. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Perception-social-farming-in-Czech-Republic-and-Stastn%C3%A1/0f928ddc5c08b38390afb90b57d7bf360ef4dcaf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Horrigan, L.; Lawrence, R.S.; Walker, P. How sustainable agriculture can address the environmental and human health harms of industrial agriculture. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, A.E.; Wittman, H.; Blesh, J. Diversification supports farm income and improved working conditions during agroecological transitions in southern Brazil. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Olio, M.; Hassink, J.; Vaandrager, L. The development of social farming in Italy: A qualitative inquiry across four regions. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 56, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, A.; Johnson, W.D.; Arendt, S.W. Breaking Barriers: Strategies for Fostering Inclusivity in The Workplace. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickafoose, A.; Ilesanmi, O.; Diaz-Manrique, M.; Adeyemi, A.E.; Walumbe, B.; Strong, R.; Wingenbach, G.; Rodriguez, M.T.; Dooley, K. Barriers and Challenges Affecting Quality Education (Sustainable Development Goal #4) in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2030. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-Roncancio, M.; Caicedo, N.R. Legislation on Disability and Employment: To What Extent Are Employment Rights Guaranteed for Persons with Disabilities? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedeler, J.S. How is disability addressed in a job interview? Disabil. Soc. 2022, 39, 1705–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.; Wilson, E.; Howie, L.J.; Joyce, A.; Crosbie, J.; Eversole, R. The Role of Shared Resilience in Building Employment Pathways with People with a Disability. Disabilities 2024, 4, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Fadden, I.; Cocchioni, R.; Delgado-Serrano, M.M. A Co-Created Assessment Framework to Measure Inclusive Health and Wellbeing in a Vulnerable Context in the South of Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulla, A.F.; Vera, A.; Valldeperas, N.; Guirado, C. Social return and economic viability of social farming in catalonia: A case-study analysis. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 398–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, C.; Uliano, A.; Marotta, G. Drivers and Barriers towards Social Farming: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarè, F.; Ricciardi, G.; Borsotto, P. Migrants Workers and Processes of Social Inclusion in Italy: The Possibilities Offered by Social Farming. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agole, D.; Baggett, C.D.; Brennan, M.A.; Ewing, J.C.; Yoder, E.P.; Makoni, S.B.; Beckman, M.D.; Epeju, W.F. Determinants of Participation of Young Farmers with and without Disability in Agricultural Capacity-building Programs Designed for the Public in Uganda. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2021, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, M.A.; Jarus, T. The Effect of Engagement in Everyday Occupations, Role Overload and Social Support on Health and Life Satisfaction among Mothers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6045–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Marty, A. Meaningful Work, Job Resources, and Employee Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldinská, K. Migrants’ Access to Social Protection in the Czech Republic. In Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 1); IMISCOE Research Series; IMISCOE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.A.; Abubakr, S.; Fischer, C. Factors Affecting Farm Succession and Occupational Choices of Nominated Farm Successors in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, L.B.; Germundsson, L.B.; Hansen, S.R.; Rojas, C.; Kristensen, N.H. What Skills Do Agricultural Professionals Need in the Transition towards a Sustainable Agriculture? A Qualitative Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrasek, G.; Horvatinec, J.; Kovačić, M.B.; Reljić, M.; Vinceković, M.; Rathod, S.; Bandumula, N.; Dharavath, R.; Rashid, M.I.; Panfilova, O.; et al. Land Resources in Organic Agriculture: Trends and Challenges in the Twenty-First Century from Global to Croatian Contexts. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinaci, T.; Russo, C.; Savarese, G.; Stornaiuolo, G.; Faiella, F.; Carpinelli, L.; Navarra, M.; Marsico, G.; Mollo, M. An Inclusive Workplace Approach to Disability Through Assistive Technologies: A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis of the Literature. Societies 2023, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekema, L.; ten Brug, A.; Waninge, A.; van der Putten, A. From assistive to inclusive? A systematic review of the uses and effects of technology to support people with pervasive support needs. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2024, 37, e13181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, X.; Bradshaw, M.; Vogel, S.L.; Encalada, A.V.; Eksteen, S.; Schneider, M.; Chunga, K.; Swartz, L. Community Support for Persons with Disabilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, J. Food consumption trends and drivers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2793–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royall, S.; Mccarthy, V.; Miller, G. Creating an Inclusive Workplace: The Effectiveness of Diversity Training. J. Glob. Econ. Trade Int. Bus. 2021, 3, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; You, C.; Pundir, P.; Meijering, L. Migrants’ community participation and social integration in urban areas: A scoping review. Cities 2023, 141, 104447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, S.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, R. Effect of organic food production and consumption on the affective and cognitive well-being of farmers: Analysis using prism of NVivo, etic and emic approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 11027–11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, L.; Chappell, M.J.; Thiers, P.; Moore, J.R. Does organic farming present greater opportunities for employment and community development than conventional farming? A survey-based investigation in California and Washington. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 552–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, I.; Edward, A.; Nkegbe, P.; Osei, R. Financing agriculture for inclusive development. In Contemporary Issues in Development Finance; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 287–317. [Google Scholar]

- Rohne Till, E. The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development. In Agriculture for Economic Development in Africa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hudcová, E. Social work in social farming in the concept of empowerment. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Agricola, H.; Veen, E.J.; Pijpker, R.; de Bruin, S.R.; van der Meulen, H.A.B.; Plug, L.B. The Care Farming Sector in The Netherlands: A Reflection on Its Developments and Promising Innovations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D.; Nassivera, F.; Bugatti, M.; Torquati, B. Consumers Demand for Social Farming Products: An Analysis with Discrete Choice Experiments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowicz, E. Farm Size: Why Should We Care? Taille des exploitations: Quel est le problème? Betriebsgröße: Weshalb ist sie überhaupt wichtig? EuroChoices 2014, 13, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, R.; Moncur, Q. Small-Scale Farming: A Review of Challenges and Potential Opportunities Offered by Technological Advancements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munćan, P.; Božić, D. Farm size as a factor of employment and income of members of family farms. Ekon. Poljopr. 2017, 64, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Korb, P.; Hoppe, R.A. Farm Size and the Organization of U.S. Crop Farming; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 1–73.

- Chandía-Rodríguez, Y.A.; Linfati, R.; Murillo-Vargas, G.; Escobar, J.W. Valuation of Active Chilean Employment Support Policies Seeking Economic Sustainability Through Market Flows. Sustainability 2024, 16, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Kerr, R.B.; Deryng, D.; Farrell, A.; Gurney-Smith, H.; Thornton, P. Mixed farming systems: Potentials and barriers for climate change adaptation in food systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 62, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, M.; Bertini, C.; Egziabher, T.; Haddad, L.; Kumar, M.; Hendriks, S.; de Janvry, A.; Maluf, R.; Aly, M.; Castillo, C.; et al. Climate Change and Food Security. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256534488 (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Ramos, A.K.; Duysen, E.; Yoder, A.M. Identifying Safety Training Resource Needs in the Cattle Feeding Industry in the Midwestern United States. Safety 2019, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, S.; Padel, S.; Lampkin, N. Labour Use on Organic Farms: A Review of Research since 2000. Org. Farming 2018, 4, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, T.C.; Mizik, T. Comparative Economics of Conventional, Organic, and Alternative Agricultural Production Systems. Economies 2021, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, F.; Psarommatis, F.; Alarcón, F.; Joan, J. A Methodological Framework for Designing Personalised Training Programs to Support Personnel Upskilling in Industry 5.0. Computers 2023, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čačija, L.N. The Nonprofit Marketing Process and Fundraising Performance of Humanitarian Organizations: Empirical Analysis. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317772097_The_nonprofit_marketing_process_and_fundraising_performance_of_humanitarian_organizations_Empirical_analysis#full-text (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Hommerová, D.; Severová, L.; Hommerov, D.; Severov, L. Fundraising of Nonprofit Organizations: Specifics and New Possibilities. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2019, 45, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacija, L.N. Fundraising in the Context of Nonprofit Strategic Marketing: Toward a Conceptual Model. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285951465_Fundraising_in_the_context_of_nonprofit_strategic_marketing_Toward_a_conceptual_model#full-text (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Stoknes, P.E.; Soldal, O.B.; Hansen, S.; Kvande, I.; Skjelderup, S.W. Willingness to pay for crowdfunding local agricultural climate solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonova, N.G.; Ozerova, M.G.; Ermakova, I.N.; Miheeva, N.B. Crowdfunding as the way of projects financing in agribusiness. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 315, 022098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugarolas Molla-Bauza, M.M.; Martinez-Carrasco, L.; Xue, Y.; Li, Y. Cohesion of Agricultural Crowdfunding Risk Prevention under Sustainable Development Based on Gray—Rough Set and FAHP-TOPSIS. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronti, A.; Pagliarino, E. Not Just for Money. Crowdfunding a New Tool of Open Innovation to Support the Agro-Food Sector. Evidences on the Italian Market. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2019, 17, 20170016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Nota, L. Colleagues’ Work Attitudes towards Employees with Disability. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Implications of Social Farming for Rural Poverty Reduction Final Report Technical Workshop; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aichner, T. The economic argument for hiring people with disabilities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.V. Is Past Performance a Good Predictor of Future Potential? 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46437632_Is_Past_Performance_a_Good_Predictor_of_Future_Potential (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Borghouts-van de Pas, I.; Freese, C. Offering jobs to persons with disabilities: A Dutch employers’ perspective. Alter 2021, 15, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Noble, C.H. Beyond form and function: Why do consumers value product design? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tej, J.; Vagaš, M.; Taha, V.A.; Škerháková, V.; Harničárová, M. Examining HRM Practices in Relation to the Retention and Commitment of Talented Employees. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, L.C.; Fraser, E.; Harris, D.; Lyon, C.; Pereira, L.; Ward, C.; Simelton, E. Adaptation and development pathways for different types of farmers. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, F.; do Rio, N.B. How to increase rural NEETs professional involvement in agriculture? The roles of youth representations and vocational training packages improvement. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 75, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).