Recommendations for Implementing Therapeutic Gardens to Enhance Human Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

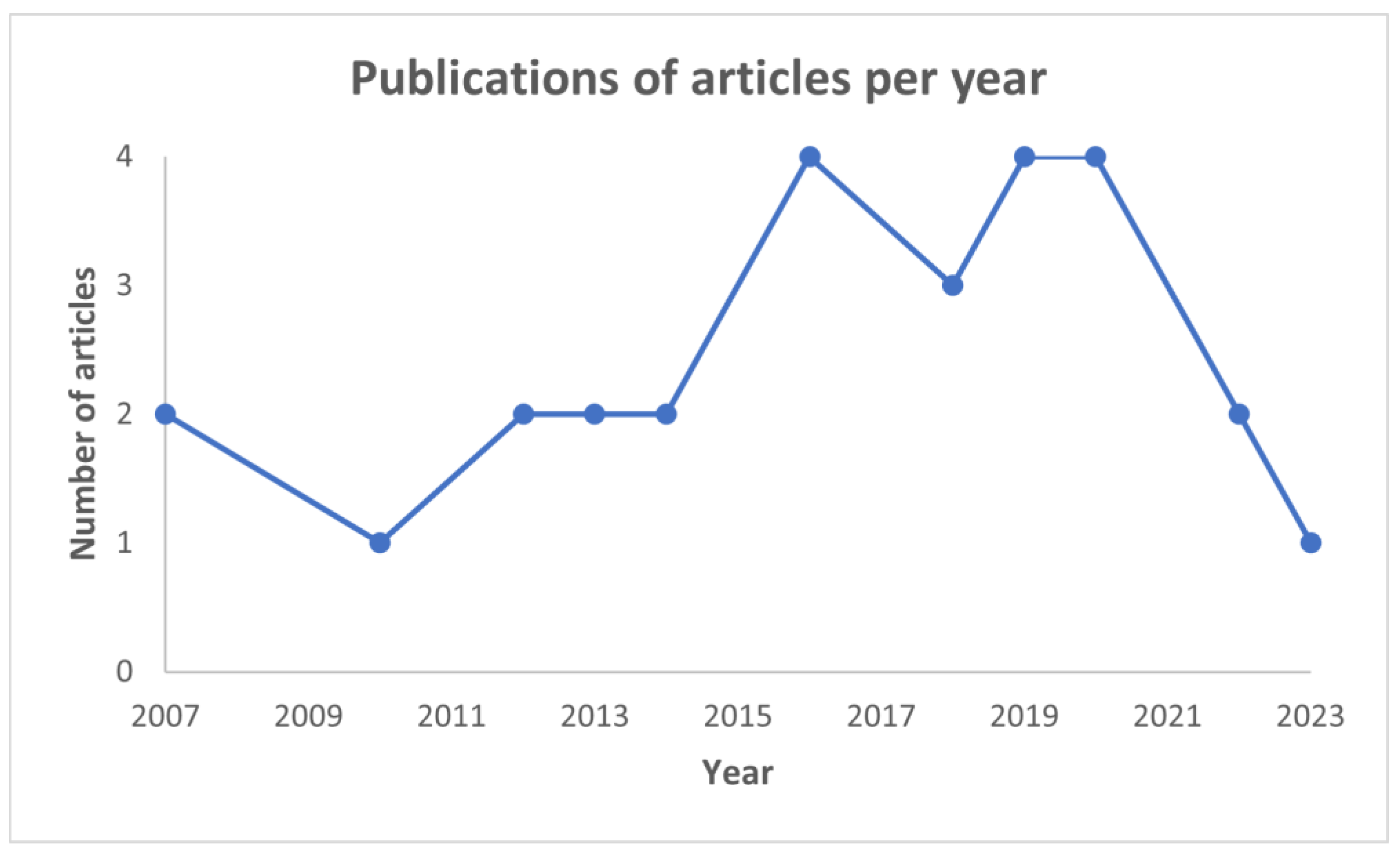

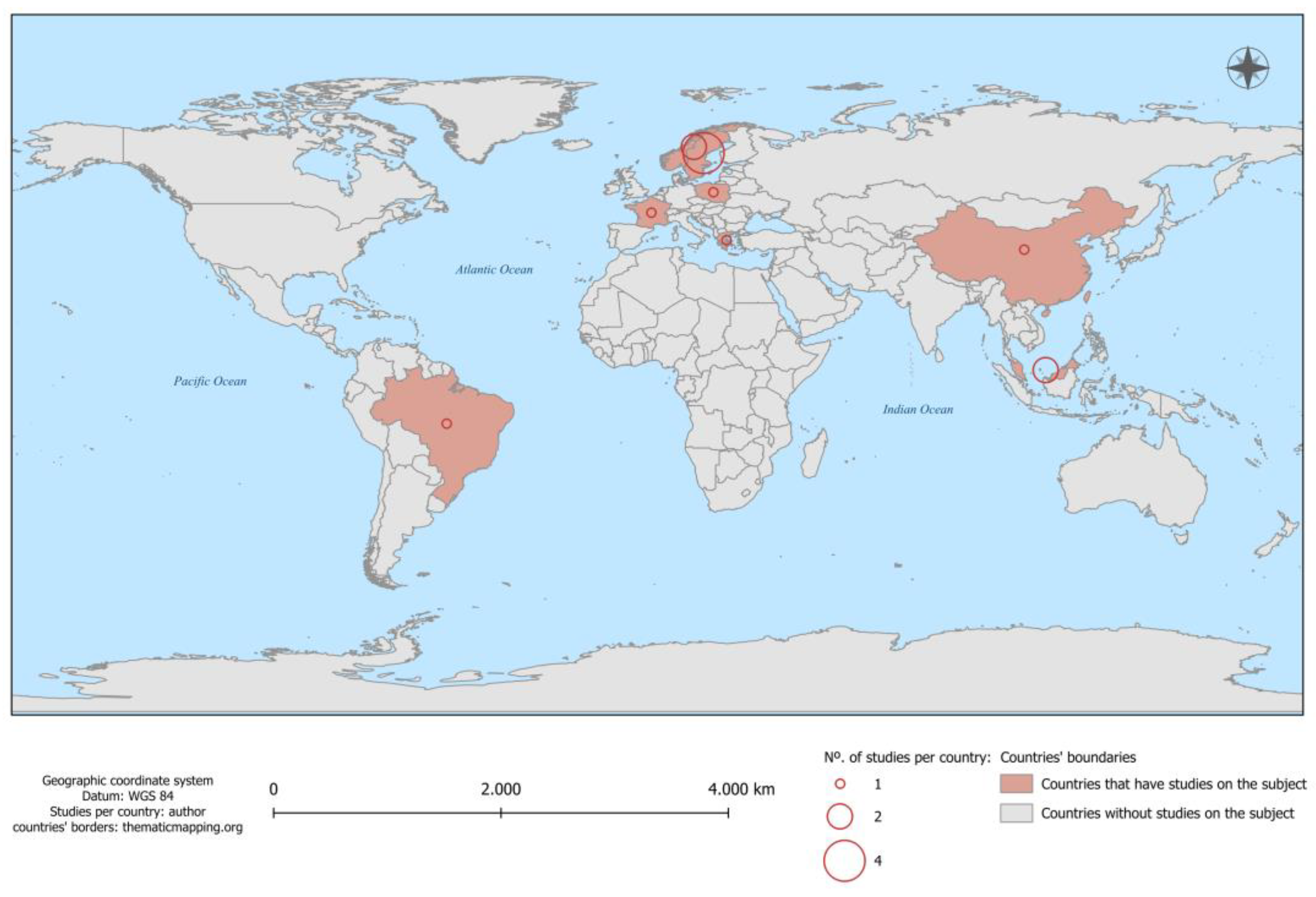

3.1. Characterization of Published Studies on Therapeutic Gardens and Design/Implementation

3.2. Experiences on the Implementation of Therapeutic Gardens in Healthcare Institutions

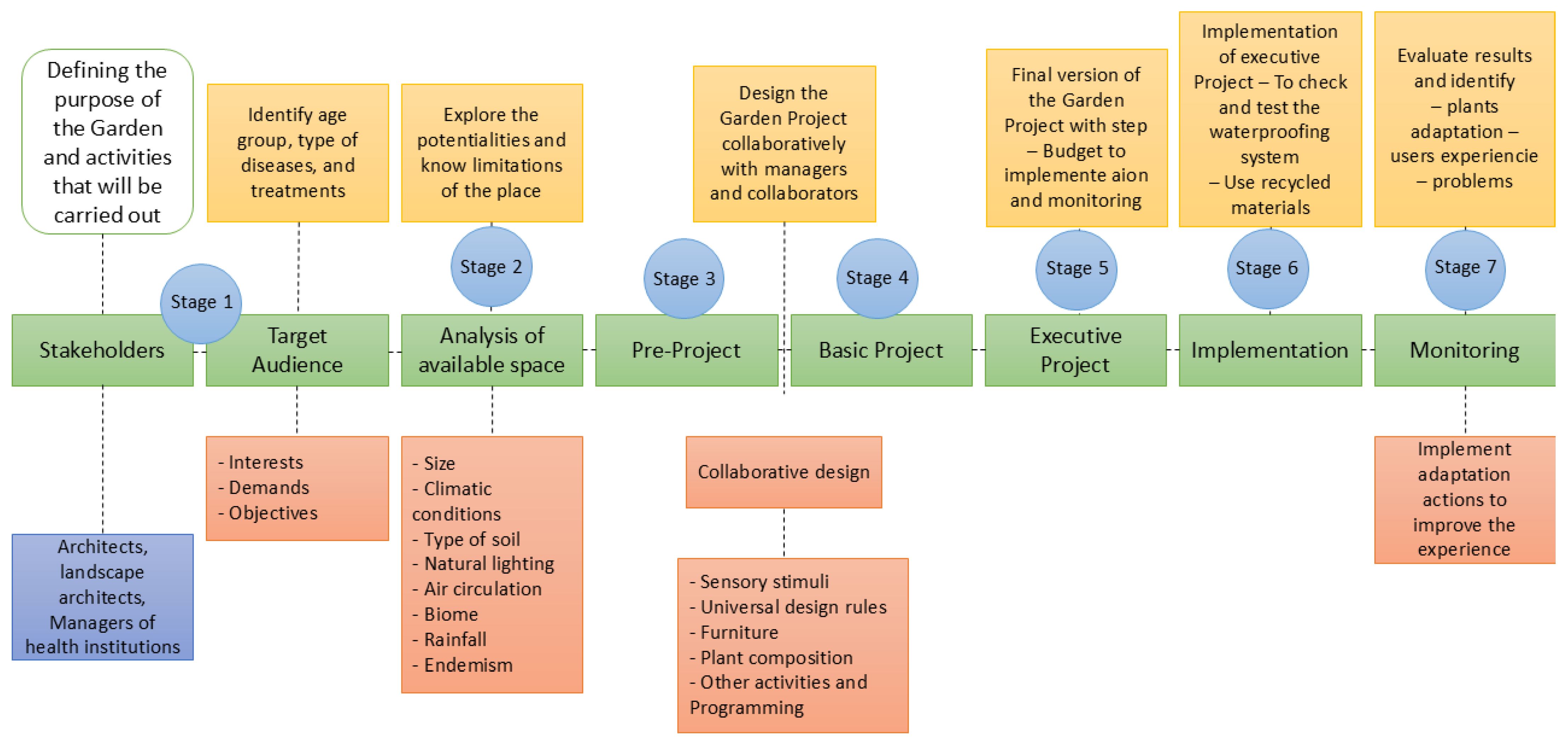

3.3. Development of Recommendations for the Implementation and Design of Therapeutic Gardens

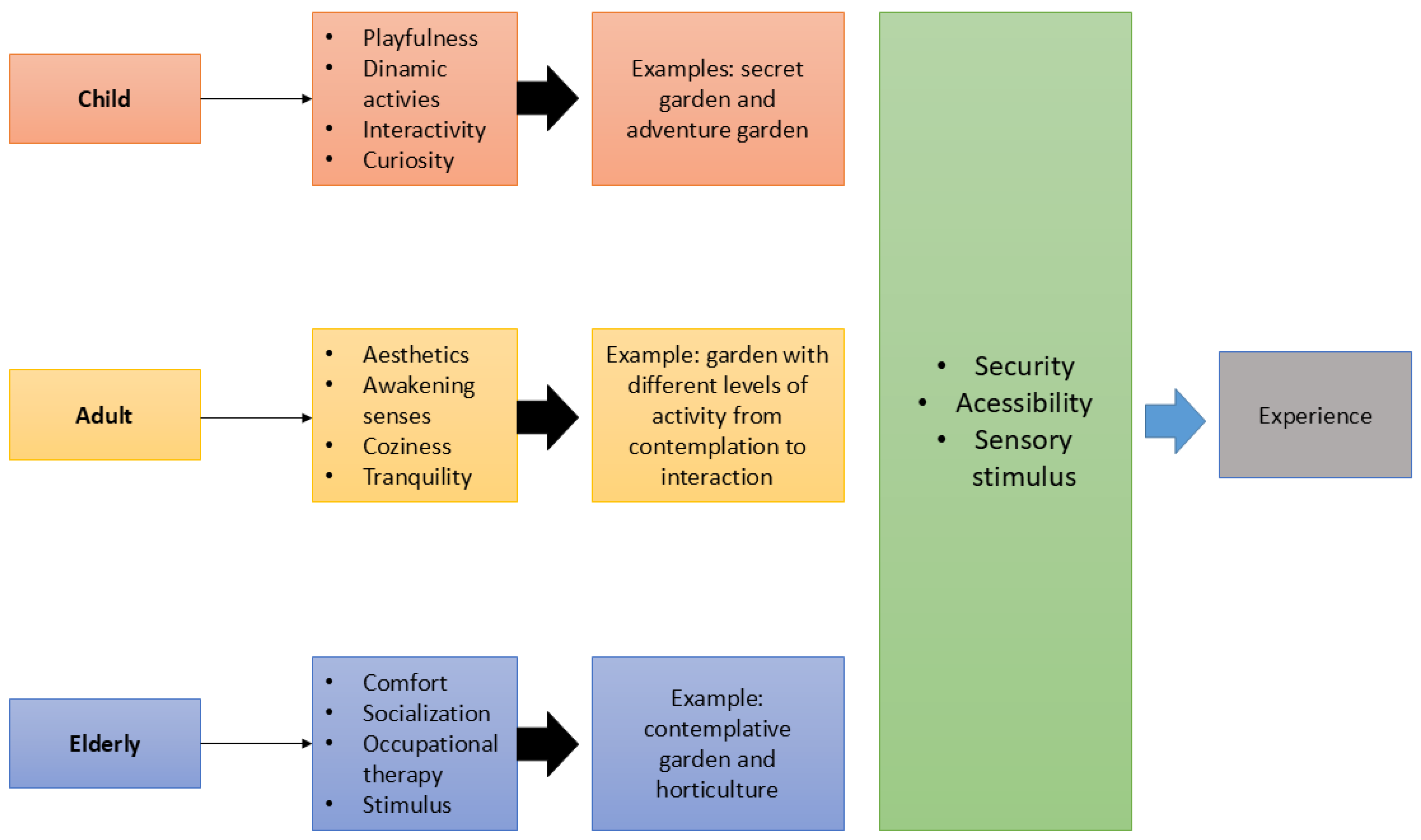

3.3.1. Stage 1: Identification and Analysis of the Target Audience

3.3.2. Stage 2: Analysis of Space and Context

3.3.3. Stages 3, 4, and 5: Elaboration of the Preliminary Design, Basic Project, and Executive Project

3.3.4. Stage 6: Implementation of Therapeutic Gardens

3.3.5. Stage 7: Monitoring of Therapeutic Gardens

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scholes, R.; Montanarella, L.; Brainich, A.; Barger, N.; Brink, B.T.; Cantele, M.; Erasmus, B.; Fisher, J.; Gardner, T.; Holland, T.G.; et al. The Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration; Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Bonn, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, A.P.F.; Padgurschi, M.C.G.; de Castro, P.D.; Scarano, F.R.; Strassburg, B.; Joly, C.A.; Watson, R.T.; de Groot, R. Ecosystem Services or Nature’s Contributions? Reasons behind Different Interpretations in Latin America. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Persson, D.; Persson, B.; Grahn, P. The Journey of Recovery and Empowerment Embraced by Nature—Clients’ Perspectives on Nature-Based Rehabilitation in Relation to the Role of the Natural Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7094–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerwén, G.; Pedersen, E.; Pálsdóttir, A.M. The Role of Soundscape in Nature-Based Rehabilitation: A Patient Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, E.; Ahlborg, G.; Tenenbaum, A.; Grahn, P. Using Nature-Based Rehabilitation to Restart a Stalled Process of Rehabilitation in Individuals with Stress-Related Mental Illness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1928–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balee, W. Footprints of the Forest Ka’apor Ethnobotany: The Historical Ecology of Plant Utilization by an Amazonian People, 1st ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Braga, F. Brazilian Traditional Medicine: Historical Basis, Features and Potentialities for Pharmaceutical Development. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Sci. 2021, 8, S44–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, W.A. “Taking the Waters”—Springs, Wells, and Spas. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1948–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, J.F. Plants in traditional medicine in brazil. J. Ethnofharmacol. 1980, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibholm, A.P.; Christensen, J.R.; Pallesen, H. Occupational Therapists and Physiotherapists Experiences of Using Nature-Based Rehabilitation. Physiother. Theory Pr. 2023, 39, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreucci, M.B.; Russo, A.; Olszewska-Guizzo, A. Designing Urban Green Blue Infrastructure for Mental Health and Elderly Wellbeing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Giannico, V.; Jim, C.Y.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Urban Forests, Ecosystem Services, Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions: Nexus or Evolving Metaphors? Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 37, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-Being of Children: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proffitti, M. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1997. Available online: https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=green+spaces (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Bloomfield, D. What Makes Nature-Based Interventions for Mental Health Successful? BJPsych Int. 2017, 14, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connellan, K.; Gaardboe, M.; Riggs, D.; Due, C.; Reinschmidt, A.; Mustillo, L. Stressed Spaces: Mental Health and Architecture. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2013, 6, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. New Urban Models for More Sustainable, Liveable and Healthier Cities Post Covid19; Reducing Air Pollution, Noise and Heat Island Effects and Increasing Green Space and Physical Activity. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitti, M. Oxford English Dictionary. 2024. Available online: https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=gardens (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- The Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2024. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/therapeutic (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Ferreira, A.B.H. Novo Dicionário Aurélio de Língua Portuguesa, 5th ed.; Positivo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010; ISBN 9788538583110. [Google Scholar]

- Kotera, Y.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effects of Forest Environment (Shinrin-Yoku/Forest Bathing) on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention —The Establishment of “Forest Medicine”. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.E.; van den Maas, J.; Hoven, L.; van den Tanja-Dijkstra, K. Greening a Geriatric Ward Reduces Functional Decline in Elderly Patients and Is Positively Evaluated by Hospital Staff. J. Aging Environ. 2021, 35, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchocka, M.; Kosiacka-Beck, E.; Myszka, I.; Niewiarowska, A. Horticultural Therapy as a Tool of Healing Persons with Disability on an Example of Support Centre in Kownaty. Ecol. Quest. 2019, 30, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwajeh, P.C.; Iyendo, T.O.; Polay, M. Therapeutic Gardens as a Design Approach for Optimising the Healing Environment of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias: A Narrative Review. Explore 2019, 15, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Kalaylioglu, Z.; Ekren, E. Use of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants in Therapeutic Gardens. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2018, 52, S151–S154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.T.; Kirkevold, M. Design Characteristics of Sensory Gardens in Norwegian Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional E-Mail Survey. J. Hous. Elder. 2016, 30, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, J.A. Design of Evidence-Based Gardens and Garden Therapy for Neurodisability in Scandinavia: Data from 14 Sites. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2016, 6, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieberler-Walker, K.; Desha, C.; Bosman, C.; Roiko, A.; Caldera, S. Therapeutic Hospital Gardens: Literature Review and Working Definition. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 260–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.L.; Ou, S.J.; Heng Hsieh, C.; Li, Z.; Ko, C.C. Effects of Garden Visits on People with Dementia: A Pilot Study. Dementia 2020, 19, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, S. Designing for Collaboration and Collaborating for Design. J. Inter. Des. 2014, 39, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.F. Landscape and Urban Design for Health and Well-Being: Using Healing, Sensory and Therapeutic Gardens. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 707–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townshend, T.G. Therapeutic Landscapes An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Re-storative Outdoor Spaces. Landsc. Res. Taylor Fr. J. 2015, 40, 1018–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.P.M.; Rodrigues, A.F.; Latawiec, A.E.; Dib, V.; Gomes, F.D.; Maioli, V.; Pena, I.; Tubenchlak, F.; Rebelo, A.J.; Esler, K.J.; et al. Framework for Planning and Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions for Water in Peri-Urban Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Systems Strengthening; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://www.who.int/home/search-results?indexCatalogue=genericsearchindex1&searchQuery=Health%20Systems%20Strengthening&wordsMode=AnyWord (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Gerlach-Spriggs, N.; Kaufman, R.E.; Warner, S.B. Restorative Gardens the Healing Landscape; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pouya, S.; Demirel, Ö. Hospital Rooftop Garden. J. Art. Des. 2017, 7, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Marcus, C.; Barnes, M. Healing Gardens Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 0471192031. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, S.; Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Cooper-Marcus, C.; Ensberg, M.J.; Jacobs, J.R.; Mehlenbeck, R.S. Evaluating a Children’s Hospital Garden Environment: Utilization and Consumer Satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whear, R.; Coon, J.T.; Bethel, A.; Abbott, R.; Stein, K.; Garside, R. What Is the Impact of Using Outdoor Spaces Such as Gardens on the Physical and Mental Well-Being of Those with Dementia? A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, S. Usability of Outdoor Spaces in Children’s Hospitals. Ph.D. Dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/775af8e6-d928-4795-8571-924f1f6f962d (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- Hussein, H. The Influence of Sensory Gardens on the Behaviour of Children with Special Educational Needs. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Riet, P.; Jitsacorn, C.; Junlapeeya, P.; Thursby, E.; Thursby, P. Family Members’ Experiences of a “Fairy Garden” Healing Haven Garden for Sick Children. Collegian 2017, 24, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. A Ultima Criança Na Natureza- Resgatando Nossas Crianças Do Transtorno de Déficit Da Natureza, 1st ed.; Aquariana: São Paulo, Brasil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, A.; Nieberler-Walker, K.; Desha, C. Healing Gardens in Children’s Hospitals: Reflections on Benefits, Preferences and Design from Visitors’ Books. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 26, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foke, A.; Sia, A.; Min, C.L.; Tang, D.; Lim, I.; Pungkothai, K.; Kwok, L.; Ng, M.; Kheng, N.C.; Biying, S.; et al. Design Guidelines for Therapeutic Gardens in Singapore, 1st ed.; National Parks Board: Singapore, 2017; p. 110. ISBN 978-981-11-3632-0. [Google Scholar]

- Eckerling, M. Guidelines for Designing Healing Gardens. J. Ther. Hortic. 1996, 8, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- El-Barmelgy, H.M. Healing Gardens’ Design Healing Gardens’ Design (Offering a Practical Framework for Designing of Private Healing Gardens). Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, H.C.B. Jardins Terapêuticos Como Uma Tendência Mundial: Seus Benefícios e Formas de Implementação. Master’s Thesis, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, S.F.F. Jardins Terapêuticos Em Unidades de Saúde: Aplicação de Uma Metodologia de Projeto Centrado No Utilizador Para Populações Com Necessidades Especiais—Caso de Estudo Do Centro de Reabilitação e Integração Ouriense. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. Available online: https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/13093 (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemeļniece, A.; Balode, L. The Transformation of the Cultural Landscape of Latvian Rehabilitation Gardens and Parks. Landsc. Archit. Art 2019, 14, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatis, F.; Egerer, M.; Correa-Guimaraes, A.; Navas-Gracia, L.M. Urban Gardening in a Changing Climate: A Review of Effects, Responses and Adaptation Capacities for Cities. Agriculture 2023, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, A.; Grahn, P. Outdoor environments in healthcare settings: A quality evaluation tool for use in designing healthcare gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, P.; Gutberg, J.; Berta, W. The Conceptualization of the Natural Environment in Healthcare Facilities: A Scoping Review. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2020, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detweiler, M.B.; Sharma, T.; Detweiler, J.G.; Murphy, P.F.; Lane, S.; Carman, J.; Chudhary, A.S.; Halling, M.H.; Kim, K.Y. What Is the Evidence to Support the Use of Therapeutic Gardens for the Elderly? Psychiatry Investig. 2012, 9, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, A.T.; Kamperi, E.; Demiris, N.; Economou, M.; Theleritis, C.; Kitsonas, M.; Papageorgiou, C. The impact of seasonal colour change in planting on patients with psychotic disorders using biosensors. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, C.T.; Grahn, P. Differently Designed Parts of a Garden Support Different Types of Recreational Walks: Evaluating a Healing Garden by Participatory Observation. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Bravo, G.M.; Quiñones-Sánchez, R.M.; González-González, M.E.; Mendez-Lázaro, G.A.; la Cruz-Luján, D.; Milton, J. Therapeutic gardens, do they influence the mental health of older adults?: A literature review. In Proceedings of the 21st LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education, and Technology: “Leadership in Education and Innovation in Engineering in the Framework of Global Transformations: Integration and Alliances for Integral Development”, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 17–21 July 2023; Available online: https://laccei.org/LACCEI2023-BuenosAires/papers/Contribution_1078_a.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Ali@Yaacob, W.N.A.W.; Hussain, N.H.M.; Nayan, N.M.; Abdullah, M.; Teh, M.Z. The preferences and requirements of green garden retirement care of the elderly: Case study at risk taiping, perak, Malaysia. Plan. Malays. J. 2022, 20, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Datta, U.; Jones, C. Promoting Health and Behavior Change through Evidence-Based Landscape Interventions in Rural Communities: A Pilot Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonveaux, T.R.; Batt, M.; Fescharek, R.; Benetos, A.; Trognon, A.; Bah Chuzeville, S.; Pop, A.; Jacob, C.; Yzoard, M.; Demarche, L.; et al. Healing Gardens and Cognitive Behavioral Units in the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: The Nancy Experience. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 34, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adevi, A.A.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Grahn, P. Therapeutic interventions in a rehabilitation garden may induce temporary extrovert and/or introvert behavioural changes in patients, suffering from stress-related disorders. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motealleh, P.; Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Dupre, K. Creating a dementia-friendly environment through the use of outdoor natural landscape design intervention in long-term care facilities: A narrative review. Health Place 2019, 58, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.C.; Parab, K.V.; An, R.; Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S. Greenspace exposure and sleep: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 109081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, M.M.Y. Therapeutic effects of an indoor gardening programme for older people living in nursing homes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, N.R.O.S.; Vicente, C.R.; da Silva, F.H. Horta terapêutica e saúde bucal: Desafios na utilização de plantas medicinais na promoção da saúde. Physis. Revista. de Saúde. Coletiva 2020, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.O. Effects of therapeutic gardens in special care units for people with dementia: Two case studies. J. Hous. Elder. 2007, 21, 117–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, J. Creating a Therapeutic Garden That Works for People Living with Alzheimer’s. J. Hous. Elder. 2007, 21, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps of the Project | Description |

|---|---|

| 1st Step: Pre-project | It consists in the presentation of the initial solution of the landscape project containing the necessary drawings for the perfect understanding of the solutions adopted. A study will be carried out by means of schematic drawings in plans, aiming at the best use of the land. |

| 2nd Step: Basic Project | It consists of the presentation of the changes that will be introduced in the preliminary project. In the Basic Design stage up to three studies will be developed to achieve the client’s objectives. |

| 3rd Step: Execution Project | It consists of the presentation of the formulated project proposal on the plants, including any modifications that may be necessary in the Basic Project, with a level of detailing that allows for the perfect execution of the project. Delivery of a botanical plan, containing specification, size, quantity of the plants and materials chosen. |

| Functionalities | Mechanisms/Forms |

|---|---|

| Awakening the senses | Mix native plants, ornamental, aromatic, and medicinal herbs; the sound of running water; birdsong, flowers with pleasant scents that attract birdlife and butterflies; colors that awaken the eye; textures that can be felt with the hands; flavors to be appreciated. |

| Cozy/comfort | Create spaces and sub-spaces with green walls within the garden itself, with different privacy dynamics; create niches that offer opportunities to stay for just one or two people, creating an intimate and cozy atmosphere; rest and meditation areas; parts with protection from the sun ans wind. |

| Interactivity | Create recreation areas; areas for group activities; areas for parties. |

| Accessibility | Implement use of color coding to improve orientation; various degrees of light and shade, access facilitation for users with and without disabilities; well-defined paths with possibilities for different walking levels; wide streets and non-slip floors accessible to wheelchair users and other people with motor limitations; signage. |

| Beauty | Provide color mixing; think about different views into the garden (coming from inside or outside the buildings); plant diversity. |

| Safety | Create well-defined and identified boundaries with plants and fences; handrails along the paths; textured materials as paving in therapeutic gardens, consisting of gravel, mulch, bark, pebbles, or even rubber, textured concrete with a brush, and synthetic grass; safe walking trails; stable surface for walking; night lighting; slip-resistant flooring. |

| Tranquility | Provide quieter, more intimate spaces. |

| Furniture and Decorative Structures | How Can It Be Used? |

|---|---|

| Easy-to-move benches, chairs, or loungers | It serves as a decoration and resting place and can be used in different arrangements (if they are furniture). |

| Bird feeders and nests | Attract birdlife. |

| Fences | Delimitation of spaces. |

| Source of water | Decoration and sensorial stimulation. |

| Sporadic raised beds with flowers to be touched | Sensory stimulation for wheelchair users (flowers would be at an ideal height so they could be touched). |

| Pergolas | For shading and resting, when used with the planting of flowering and fragrant climbers. |

| Gazebo | For resting and an intimate place for reading or being with oneself in moments of reflection. |

| Sculptures | They evoke past or recent memories. They sharpen cultural memories and promote surprise elements in the garden. |

| Walls | Protection, limitation of spaces. Ideal with living fences with plants that form hedges to cover the entire wall. |

| Mosaics | To awaken curiosity, attention, and positive distraction through stimulating formatting, colors, and designs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pimentel, H.C.B.; Lima, A.P.M.d.; Latawiec, A.E. Recommendations for Implementing Therapeutic Gardens to Enhance Human Well-Being. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219502

Pimentel HCB, Lima APMd, Latawiec AE. Recommendations for Implementing Therapeutic Gardens to Enhance Human Well-Being. Sustainability. 2024; 16(21):9502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219502

Chicago/Turabian StylePimentel, Helena Carla B., Ana Paula M. de Lima, and Agnieszka E. Latawiec. 2024. "Recommendations for Implementing Therapeutic Gardens to Enhance Human Well-Being" Sustainability 16, no. 21: 9502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219502

APA StylePimentel, H. C. B., Lima, A. P. M. d., & Latawiec, A. E. (2024). Recommendations for Implementing Therapeutic Gardens to Enhance Human Well-Being. Sustainability, 16(21), 9502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219502