Abstract

Cities face increasing heat risk due to global and local warming, and the risk is greater in the developing world. South Asia, in particular, faces increasing urban climate risk, but the translation of urban climate knowledge into sustainable climate-sensitive planning is weak. In this paper, we report on our conversations with experts from the Sri Lankan urban planning community on the barriers to and opportunities for urban climate mitigation action. We uncover six themes (insights, integrate, specify, exhort, commitment, and continuity) that best exemplify both the barriers to and opportunities for enhancing heat risk resilience in this primate city. We then map a set of agencies and actors that need to be involved in any holistic risk resilience plan and draw wider lessons to sustainably manage the urgent practical gaps in heat health planning.

1. Introduction

The increasing heat risk in cities is due to the combination of global climate change and the more local microclimate anomaly known as the urban heat island (UHI) [1]. Following the IPCC convention of ‘risk’ as a function of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability [2], the increasing urban heat risk is due to rising temperatures (‘hazard’), especially the wet-bulb temperature [3]; the increasing urban population (‘exposure’), especially in the developing world [4,5]; and poverty and lack of essential services (‘vulnerability’), particularly in the developing world.

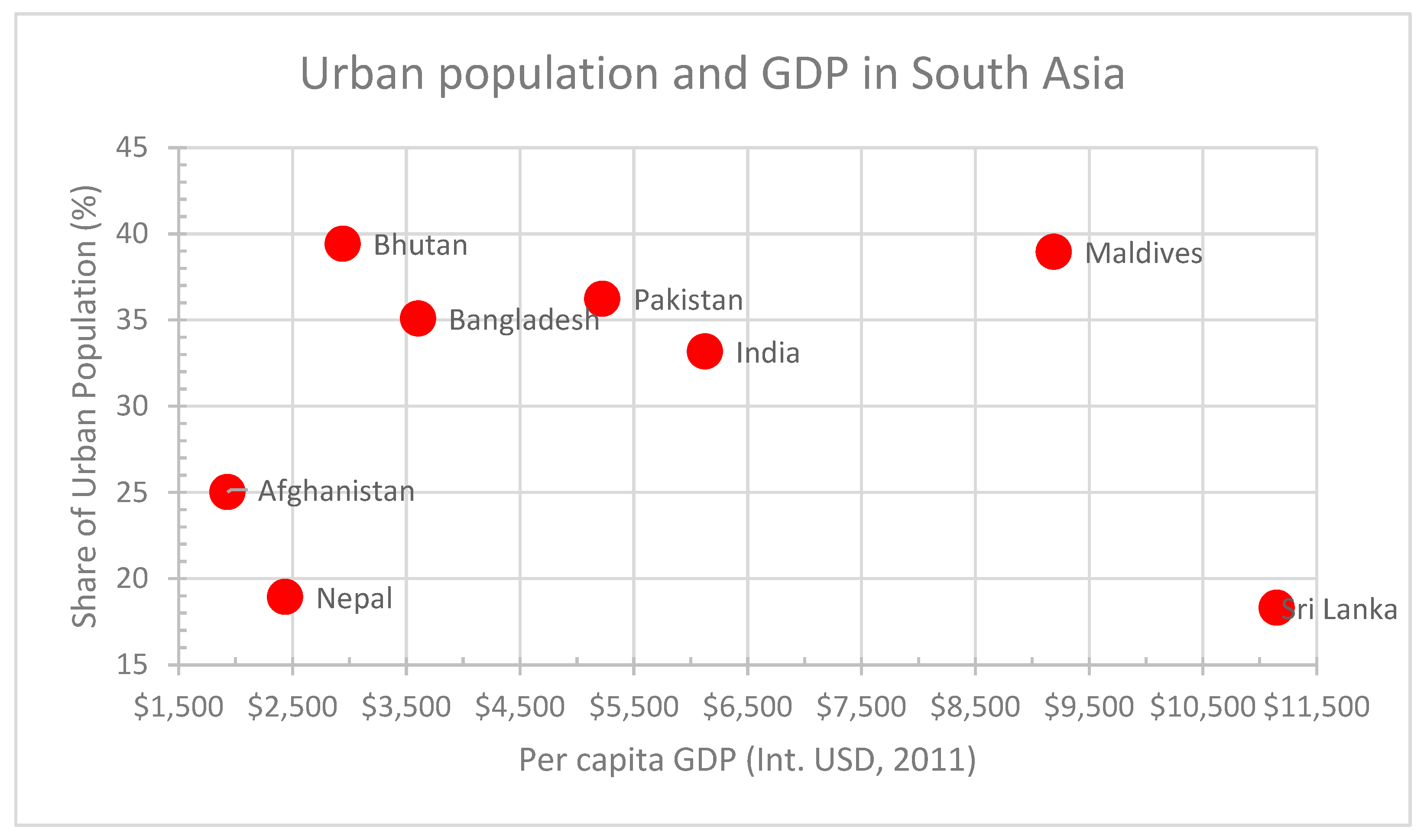

The health and wellbeing consequences of urban warming are particularly problematic in South Asia. On the one hand, the relative share of urban warming, when compared to total warming, is very high in South Asia (reaching up to 76% of the total warming in cities such as Kolkatta, India [6], and averaging approx. 60% across the region [7]). On the other hand, rapid urbanisation, albeit from a low base (see Figure 1), and urban poverty magnify the risk. Approximately half of the urban population in South Asia lives in slums (see Our World in Data—https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization#urban-slum-populations, accessed on 27 October 2024).

Figure 1.

Share of urban population and per capita GDP in South Asia. Source: Plotted from data by ‘Our World in Data’ (https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization#how-urban-is-the-world, accessed on 27 October 2024) and ‘World Bank’ (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD, accessed on 27 October 2024).

The urbanisation and growth situation in Sri Lanka is particularly unique, as can be seen in Figure 1. Starting from a very low base of less than 20% till the end of the 20th Century, the recent growth in the urban share of the population, following the end of civil conflict in 2009, is rapid. Our previous work [8] has shown a particularly striking warming trend in Sri Lanka. Based on a thermal comfort index—the Universal Thermal Climate Index, UTCI—Sri Lanka’s average heat stress in the hottest month (April) is close to ‘extreme heat stress’, while the situation in the coolest month (January) is fast approaching ‘High heat stress’ across the country [8]. This work further showed that well-known urban climate mitigation options, such as shading and green cover, could reduce heat stress, even in the hottest month, but their utility will diminish unless climate change itself is moderated. Despite this and unlike elsewhere in South Asia (such as Ahmedabad, India), where recent heatwaves have led to the development of heat action plans (HAPs) [9], Sri Lanka does not possess a HAP at present. This is despite the warning by the Sixth Assessment Report of the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which stated that humid heat stress in South Asia will be more intense and frequent during the 21st century [7]. Although early efforts to develop heat health warning systems specifically targeted at urban areas are beginning to appear in India and Pakistan [10], these need to be deployed more widely across the region.

Urban planning and design approaches to managing heat risk in warm climates are widely known. Designing buildings to shade interstitial spaces is a possible approach to enhance outdoor comfort, as recognised by concepts such as the ‘Shadow Umbrella’ [11]. Promoting airflow is another approach to thermal comfort enhancement in warm climates by way of managing the form of buildings (e.g., courtyard form [12]), orientation of buildings along major ventilation axes [13], step-up form of building arrangement [14], and a combination of shading and ventilation approaches [15]. A third approach to overheating management in warm climates is green infrastructure (continuous tree cover in streets and [16] appropriate selection of tree species [17] in combination with shading [18]). High-albedo materials could contribute to mitigating the urban heat island effect in warm areas and improve thermal comfort in outdoor spaces [19,20,21], although evidence for their universal efficacy is weak [22,23,24]. Furthermore, land use morphological characteristics play a more important role in urban thermal environments than landscape patterns [25].

Yet, this knowledge remains poorly exploited in urban planning practice, particularly in South Asia. We hypothesise that the lack of exploitation of climate knowledge in planning is due to governance, policy and personnel-related challenges facing the urban planning community. Additionally, there may also be challenges related to the awareness of the magnitude of the heat risk and the rapidity of the changes in heat risk. Given the scale of the problem and the availability of climate-resilience knowledge, the present work aims to understand the existing administrative barriers to knowledge sharing in climate-sensitive urban planning and points of possible interventions to translate the available urban climate knowledge to planning practice.

2. Context

Colombo, the commercial capital of Sri Lanka, has had a long history of formal attempts to regulate its urban growth (see Table 1). Since the establishment of the Colombo Municipal Council over 150 years ago, ‘environmental’ matters (including forestry, disaster mitigation, public health, and, lately, climate) have been considered in the city’s many developmental regulations. While there is general awareness and consideration of Colombo’s tropical climate, the rapidly changing local climate is not well-acknowledged in the planning policy framework in Colombo or Sri Lanka as a whole. Our prior work [8] has shown that the hottest month (April) areas that were previously classed as ‘very strong heat stress’ in the 1990s are moving towards ‘extreme heat stress’ in the 2010s, covering over two-thirds of the landmass of Sri Lanka. Even in the coolest month (January), ‘moderate heat stress’ unknown in the 1990s is now becoming a common trend across the most densely populated regions. This work further showed that high shading and vegetation levels could reduce heat stress, even in the hottest month, but their utility will diminish as the warming continues in the future. As will be seen in Section 4 below, our informants were very clear that this type of local climate considerations is not integral to the planning approach in the city.

Table 1.

Relevant developments in urban governance in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Agencies are highlighted in green.

3. Materials and Methods

We conducted an in-depth inquiry into the lived professional experiences in climate-sensitive planning in Sri Lanka to explore subjective viewpoints. Expert opinions were sought out, and semi-structured interviews were conducted.

Our starting point was the previously published work [8], which clearly showed the warming trends in Sri Lanka and the possibility of arresting them through known urban climate mitigation strategies, such as shading and vegetation. We conducted a pilot study to disseminate this work among a large group of urban planning professionals (forty) and to gather practitioner thoughts on key challenges that needed to be explored more in detail with experts. The pilot work also helped us identify experts with direct experience in the Sri Lankan urban planning system. Given that our purpose was to develop a nuanced understanding of the ground realities in climate-sensitive urban planning practice (or lack thereof), we used the leads arising from the pilot study to reach out to experts with direct experience of the Sri Lankan urban planning system (and in particular, its interactions with climate-sensitive planning sub-domain). Thus, a purposive sample, rather than a random sample, is appropriate for the present purposes. We used a ‘semi-structured’ approach to the interviews, in which a list of key points identified in the pilot study formed the basis of the interviews. We then presented to the shortlisted experts our findings on the country’s urban thermal comfort trends and the likely effect of selected planning strategies to mitigate the trends. This led to four broad categories of questions: Colombo planning context, climate change in Sri Lanka, climate-sensitive design strategies, and the implementation of design interventions in urban planning. These helped to inform the interview questions (around thirty).

The themes and the ‘semi-structured’ approach facilitated the smooth flow of the interviews and helped us work through them in a methodical manner. While we asked similar questions of all interviewees, supplementary questions were asked as appropriate. We aimed to cover all nine types of interview questions specified by [26], although the interviewees were free to respond as they pleased and did not have to ‘tick a box’ with their answers.

Using a snowballing approach from our large pool of pilot study participants, we settled on six experienced professionals who have contributed to shaping the planning landscape in Sri Lanka for interviews—two each from the academic (AC), practitioner (PR), and administrative (AD) communities. A summary of interviewee characteristics is tabulated below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of interviewees.

We conducted one-on-one online interviews during the months of March to June 2021 and each interview lasted around 60–90 min. Open-ended questions were asked mainly to focus on the existing planning context and urban climate in Colombo.

The interviews were then analysed using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a popular method of qualitative analysis that explores insights through patterns of meaning (themes) that occur around a dataset by systematically grouping and organising it [27].

Since the pioneering attempt to outline a pragmatic view of thematic analysis [28], several methods have emerged on how to perform a proper thematic analysis that could be applicable to a wide range of research areas. We followed a six-phase approach to thematic analysis [27], as follows:

- Familiarising yourself with the data;

- Generating initial codes;

- Searching for themes;

- Reviewing potential themes;

- Defining and naming themes;

- Producing the report.

All interviews were recorded and automatically transcribed using Microsoft Office software Ver. 10.0 (Word Web app). The transcribed files were then coded, initially using the themes derived from the pilot study. The search for themes and review of potential themes were facilitated by NVIVO-12 pro software, which enabled the grouping and re-grouping of hundreds of codes to achieve a coherent set of themes. This was performed at the end of each interview. By the end of five interviews, we reached the saturation point, and the sixth interview merely repeated the derived codes. This reinforces our view that all major points addressing urban climate mitigation actions are covered by the interviews. Hence, Section 4 presents only the first five interviews.

4. Results

4.1. Themes—An Approach to Implementation

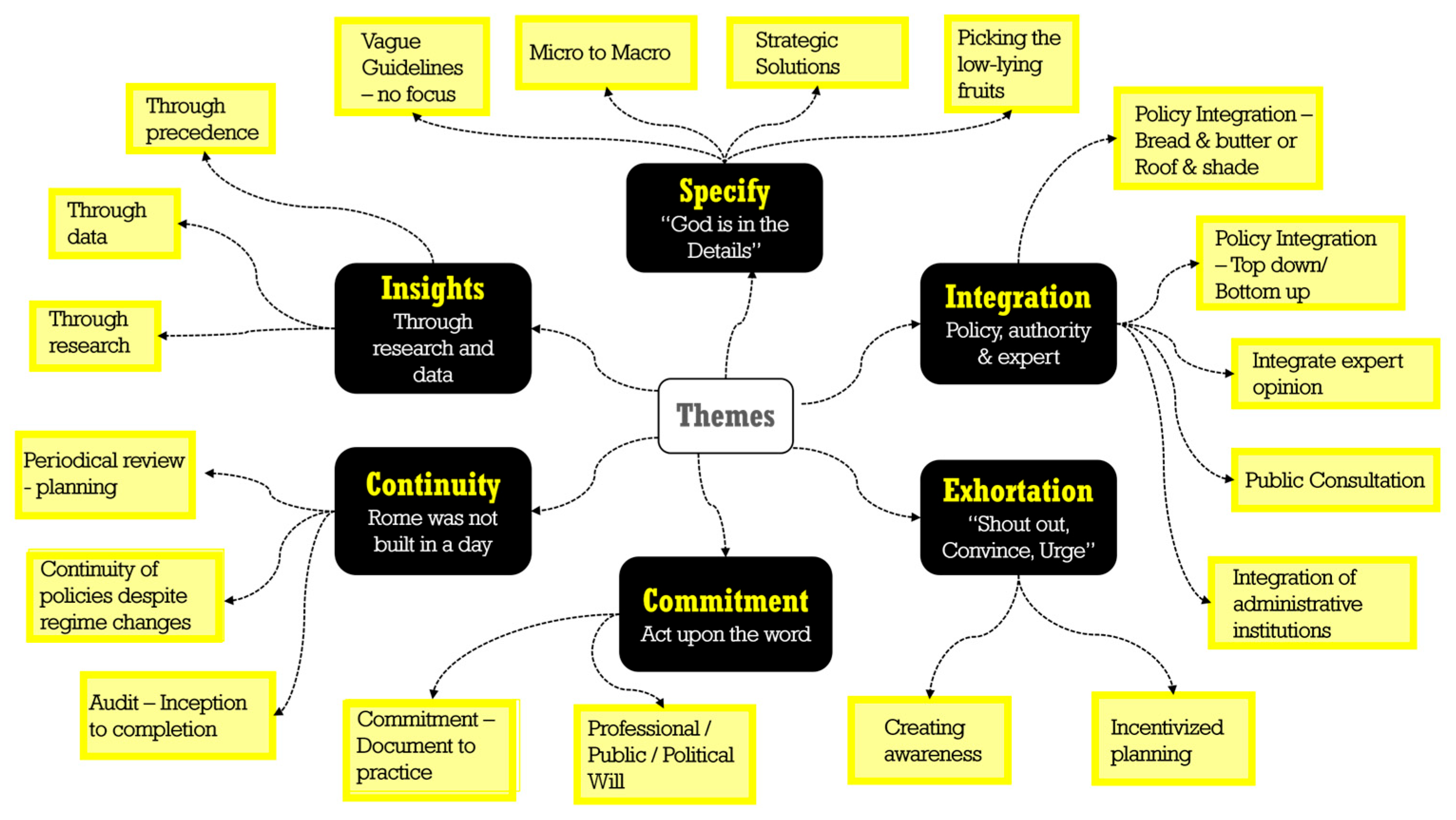

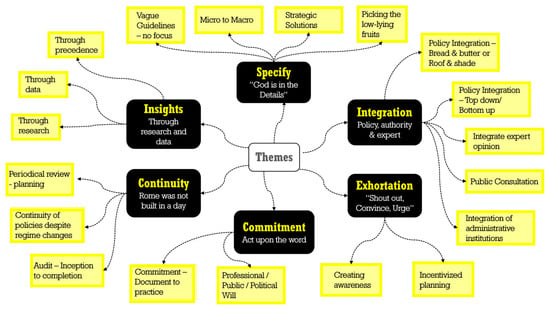

The thematic coding results provide ‘meanings implied’ and insights into the nature of the current planning environment and strategies to integrate climate-sensitive planning into the overall urban planning process. The themes and subthemes generated from the analysis are depicted in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Themes and subthemes from the interviews.

4.1.1. Insights—Through Research and Data

- a.

- Through research

One of the questions aimed to gauge existing climate knowledge in Sri Lanka, for which we obtained mixed answers from the participants. Two participants clearly identified the need for contextualised local research: ‘most of the studies are very general studies, where we can’t make any decisions’. Since the importance of context can never be underestimated in climate studies and strategies [29], it is important that academia encourages more specific studies that contribute to practical applications (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Details of Theme 1.

Similarly, the quality of research is important. One of the practitioners, PR1, identified that there was limited research on the local urban climate, and the quality of research seems to be less focused and ineffective when formulating ground-level solutions and attributes.

The need for quantitative research was stressed by AC2, who claimed that quantitative research can sometimes be isolated, assumption-based, and obtained with erroneous or manipulated data.

- b.

- Through precedence

Throughout the interviews, there were references to the pros and cons of precedence from other countries. Some encouraged ‘learning lessons from other cities without reinventing the wheel’, while others claim that precedence can only be a starting point and not the end results of implementation due to different local perceptions. PR2 stated, ‘We need to have our own system of determining these things—our comfort level is completely different for a person in Europe. Their comfort level may be too cold for us. Thus, we need contextualized modification of urban climate parameters, rather than borrowing from the West’.

One participant further claimed that solutions based on other countries should be critically questioned prior to implementation in our context considering our socio-economic and geographical context. They stated ‘You can’t compare Singapore and Hong Kong with Sri Lanka, their mindset is different, the focus is different… these are high density, well-developed cities. The Megapolis Development Plan (Govt. of Sri Lanka, 2004. Western Megapolis Master Plan, https://www.jll.com.lk/en/trends-and-insights/investor/western-megapolis-master-plan, accessed on 27 October 2024) is a failure as we have tried to imitate Singaporean designs’.

- c.

- Through data

Ref. [30] defines the three components of knowledge as data—the lowest point, an unstructured collection of facts and figures; information—structured data; and knowledge—information about information. Although we can gain a lot of insights through data, organised ways of storing, categorising, and centralising data for future use (i.e., information) are key to knowledge in the current context.

Both practitioners we interviewed asserted the importance of having data recorded and available in a centralised databank for future use. This could be past climate disasters, surveys, reports, modelling exercises, simulations, etc. They also stressed the importance of coordinated data and having previous models/simulations available for use by future designers.

PR2 contended that the data collated by the meteorological department stand in isolation and are not utilised by the Urban Development Authority (UDA). This is similar to what other researchers found previously (e.g., Ref. [31] calls for the integration of meteorological data in the planning system for useful urban climate actions.)

4.1.2. Integration—Policy, Authorities, and Expert Opinion

- a.

- Integration—Bread and butter OR roof and shade?

When we discussed the opportunities for prioritising urban climate-sensitive decisions in the planning process, most participants qualified that ‘we need climate actions, but there are other priorities…’, where the priorities are social and economic challenges. Thus, we coded this theme in the integration of urban climate policies as a ‘second-order planning decision’ (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Details of Theme 2.

‘Unless we integrate social, financial and cultural benefits, implementation of climate mitigation strategies will tend to fail’. –PR1.

The key challenges that govern the planning landscape, as posited by the participants, are social—especially housing, transport and waste management.

AC1 stated that ‘… there is more than 50% of under-served settlement in Colombo. There has been a long-term agenda in addressing this, but still we have failed to find a successful solution…’. Echoing the same idea and adding depth to it, AD1 stated that ‘… Colombo is a wetland-based city—we need to plan based on the ecological strength of the city. These wetlands provide ecosystem services, but encroachment into wetlands and marshes has posed a serious threat’.

Encroachment and urban sprawl are serious problems in Colombo that have not been addressed adequately in the past [32,33]). AD1 stated that ‘Colombo being the primate city has attracted a lot of demand pressure over the years. Infrastructure development, transport, waste management have been unresolved issues for decades, and the high demand for development will only make it more challenging in addressing these’.

However, there was agreement that we need to cater to this demand. Commenting on the existing regulations as ‘restrictive in nature’, AC1 stated that planning regulations must consider market forces and allow optimum built form, thereby encouraging developments.

The discussions also highlighted the crucial necessity to address climate disasters, such as urban flooding, landslides, the degradation of air quality, etc., through planning practices. AC2 acknowledged that urban warming mitigation should be a priority in planning but must be integrated with other policies. There should be a balance, as ‘…ultimately it all boils down to the bread and butter of common man …’ (PR1).

When discussing the key concepts within sustainable development, [34] recognised that social and economic practices are inseparable from sustainable development. Sustainable development needs to be integrated within socio-economic policies. This is also advocated by the New Urban Planning—Vancouver Declaration [35]. However, by prioritising climate mitigation strategies, countries can minimise unnecessary economic burdens associated with post-disaster recovery and establish a healthy workforce. This leads to a debate about whether climate mitigation strategies should be considered second-order strategies or first-order strategies, especially in a developing country like Sri Lanka, due to the fact that neglecting climate risks has led to severe climate disasters in the recent past.

- b.

- Policy integration—top-down/bottom-up

While discussing whether urban climate actions can be governed, PR1, AD1, and AC2 stated that they can easily be governed from a top-down approach due to the structure of urban governance in Sri Lanka. The command-and-control structure makes it relatively easy to impose regulations that will trickle down to ground level.

On the contrary, AC1 and PR2 stated that urban climate actions should be governed using a bottom-up approach. Even though policies are imposed, they could be easily manipulated by the ‘middle management’, i.e., regulatory agencies, which have the power to thwart implementation. Due to corruption and malpractice, this might not be implemented effectively or rather end up only in documents. However, if the public is aware of the adverse climate effects and there is a strong desire to carry out climate action among the people, the middle management will also feel pressure from the bottom.

AD1, AC1, and PR1 insisted on the need for public participation in the planning process. PR1 said that the Indigenous knowledge of traditional architecture was very much based on thermal comfort, and the planning process can and must gain insights from them. Additionally, AC1 indicated the need to involve the public to dissipate climate knowledge and make them aware.

- c.

- Integrate expert opinion

The interviews confirmed that integrating professional inputs at the beginning of the planning process and integrating them throughout the implementation process is a positive reinforcement in urban climate mitigation strategies.

PR1 said that ventilation modelling for downtown Colombo revealed that high-rise buildings could actually improve the wind flow of the city. These sorts of evidence-based revelations can help create a thermally comfortable environment while at the same time encouraging development, thereby creating a conducive environment for attracting urban investments.

PR1 and AD1 suggested that it would be necessary to have a town planner-led assessment that consisted of all necessary checkpoints—climate, environmental, material, urban warming, waste management, etc. We were also told that this has been proposed by the UDA as a measure to integrate professional input in planning but has not yet been implemented.

Apart from policymakers approaching professionals, professionals should also take the initiative to voice their opinions. We categorise these suggestions under Theme 4—‘Exhortation’.

This is similar to other suggestions found in the literature. For example, with the growing importance of sustainable urban planning, policymakers and planners are responsible for identifying thermally vulnerable areas in the city, and they plan accordingly, which requires knowledge and expert input [36].

Based on recent experience in leading a new urban development proposal, one of the participants claimed that the new proposal better integrates expertise from various fields and utilised holistic and contextualised solutions, such as green areas along water bodies to mitigate urban warming. They further stated that ‘although there are claims of many sustainable developments, most of these don’t integrate expert opinion at the very beginning and are often add-ons which is often a makeover/afterthought process’.

- d.

- Public consultation

There was a strong consensus that public consultation should be a key part of climate-sensitive and sustainable planning. AC1 stated that involving the public during the planning process will not only allow Indigenous knowledge to integrate with planning but also allow the public to be informed regarding the benefits of climate-sensitive planning and design. They further pointed out that there is no existing system in the planning process in Sri Lanka that informs the public regarding neighbourhood development and that if the locals are informed and involved in the planning process itself, there could be more control over developments.

AD1 and AC2 both implied the need for regulating public consultation as a mandatory requirement in the planning system for effective climate mitigation strategies. This finding is similar to that of the authors of [37], who researched inclusive approaches to urban climate adaptation planning and implementation in the Global South. They found that participatory approaches lead to higher climate equity and justice outcomes in the short term, whereas integrating multi-sector organisations will lead to long-term programme stability.

- e.

- Integration of administrative institutions

One of the significant barriers we identified in implementing climate-sensitive planning is the fragmentation of administration and thus institutional decision-making. This was brought up by all the participants and thus led to the easy identification of a subtheme.

When we inquired about existing climate awareness amongst stakeholders, PR1 said that while there is a considerable knowledge base, this is not being effectively implemented, mainly due to the existence of several planning agencies with overlapping responsibilities.

PR2 indicated that the implementation of development plans is ‘not even 50% efficient’ and indicated the fragmentation of institutions as a key reason for this. ‘The NPPD (National Physical Planning Department) develops plans at the national level, but these are not backed by financial plans. They only work within their own scopes. Thus, the plans mostly end up in only documents’. PR1 also indicated that the separate Climate Change Secretariat and Environmental Ministry are not synchronised in an effective way to provide solutions. Further, they indicated that this can lead to finding a loophole rather than consciously responding to the situation.

This is consistent with what the authors of [38] found when analysing the structure of policymaking in Australia. They stressed that consistent and coherent development plans are achieved through the coordination of central agencies and identified that these agencies are vital to the task of policy coordination.

4.1.3. Specify—‘God Is in the Details’

This was the most referenced theme, with 68 references throughout the interviews, and it was constructed with ideas revolving around ‘lack of detail’ and ‘the need for conscious specified regulations’ (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Details of Theme 3.

- a.

- Vague guidelines—no focus

All the participants explicitly stated that existing regulations were very vague and not detailed enough. AC1 and PR2 suggested that the development plans were not focused on urban climate issues, and PR2 further elaborated that ‘…the existing development plan is not adequate to address climate issues, let alone other issues such as transport, waste management etc…’ and ‘… the CDP (Colombo Development Plan) is very generic and not specific, I would say that CDP is more a regulatory plan than a development plan…’.

Local authorities and the UDA control most developments in Sri Lanka. The CDP is the ground-level guidance for any development in Colombo, and specifying this in detail will allow for more control over development.

- b.

- Macro to micro

The existing development plans were identified as mere zoning approaches that needed much more detail.

AC1 stated that ‘The current plan is limited to only zoning and building heights, and since there are no specific guidelines, one can easily manipulate the regulations, especially investors and politicians’. PR1 and PR2 also acknowledged that existing zoning-based guidelines could be easily manipulated. AD1 stated that zoning was a good initiative but must be detailed.

AC1, PR1, and PR2 discussed moving to the ‘next level’ of zoning—developing regulations for districts, neighbourhoods, streets, etc. PR1 and AC1 said that we need to consider detailed design guides for clusters or neighbourhoods while developing regulations to address UHI/UW issues. They elaborated on this, stating the following:

‘…our building regulations are single entity focused—the concerns are only the plot. Spaces in between the buildings are not covered. Wind flow within neighbourhoods, shading effect from adjacent buildings etc. are not considered…’–PR1.

PR2 further stressed the need to consider smaller districts in planning while drawing examples of Singapore planning, in which guidelines are based on smaller areas and lead to more sensible plans.

Through the interviews, we understood that classifying building typologies could be an effective method for developing regulations. PR1 indicated that we should change the paradigm of how we look at our building regulations to implement effective detailed guides, as follows:

‘…our regulations are more land oriented—land-use based. If we are concerned about these heat island and urban warming issues, we need to focus more on building typologies rather than land uses. We need to address these issues at a policy level’.

The issues in the existing guidelines were discussed in detail. Our informants felt that they are developed on a broad zonal basis (i.e., the whole city) and/or focus on building scale (in terms of setbacks, energy consumption, etc.), leaving the middle ground (policies focused on the interstitial spaces) largely uncovered.

- c.

- Picking low-hanging fruits

When discussing the urgency of climate-sensitive planning, we understood that the preparation of detailed guidelines will take time. PR2 and PR1 suggested implementing a ‘hassle-free planning process’ for smaller developments. This can be detailed to encourage urban climate mitigation, such as retrofitting existing buildings to encourage shade, greenery, etc., and converting impermeable material to permeable/thermally reflective materials, etc.

Integrating climate checkpoints can also be attributed as immediate measures to tackle the incorporation of urban climate actions and will also create awareness amongst professionals and the general public. AC1 suggested incorporating the town planner’s assessment and accepting it as a requirement by donor agencies as an immediate measure.

- d.

- Design strategies

We constructed this subtheme as a summary of all design strategies discussed during in-depth discussions. Firstly, we solicited interviewee opinions on four well-known urban climate mitigation strategies (Table 6). We then explored local climate mitigation ideas at different scales (regional/local/building-scale) that are specific to Colombo as given in the Colombo Development Plan (Table 7). The former was suggested by us and was based on the literature, as outlined in Section 1 of the present paper, while the latter was jointly developed based on the literature, as well as local development plans.

Table 6.

Interviewee responses to known urban climate ameliorating strategies.

Table 7.

References to design approaches in governance documents (listed in Table 4) at different scales (regional, local or micro level).

Table 7 confirms that most of the design strategies mentioned by the interviewees were similar to those reflected in the urban climate literature. However, these were not captured in the development plans of the city (such as the CDP), which has been deemed a huge gap in the existing planning regime.

4.1.4. Exhortation—Shout Out, Convince, Urge

Exhortation means to strongly encourage/urge someone to do something. Urban climate action is a collective measure, and thus will not be effective unless a strong persuasion is involved, especially in the Global South, where the primary concern of the majority revolves around ‘bread and butter’ issues of livelihoods (See Table 8).

Table 8.

Details of Theme 4.

- a.

- Incentivise

PR1 stressed on several instances during the conversation that climate-sensitive design approaches should be tied to benefits—specifically financial benefits—to encourage uptake. These could be incentives, subsidies, loans, tax concessions, etc. They also addressed the lack of motivation to implement other good practices in the current development plan. This way, a developer can give something to the city while benefitting financially from the development.

- b.

- Creating awareness

All participants implied that awareness is a requirement for successful urban climate action. AC2 stated that ‘making people aware and convincing politicians’ is essential to practically incorporate checkpoints; if not, they might end up as mere checkpoints to gain a tick in the documents.

AC1 reflected on the abovementioned idea, further stressing that communication strategies should be tailored according to the target groups, i.e., the public, professionals, and investors, accordingly, rather than mass communication strategies. The same message can be delivered via different formats to different groups. They also implied that it is the responsibility of the professionals to voice their inputs and opinions to bring change to the system.

When discussing the possibility of a change in the planning system with a focus on urban climate actions, AD1 advocated the integration of climate awareness and heat-related health issues in the education systems as follows:

‘We can’t bring change overnight. But we can educate the future generation. I strongly believe if there is a programme to integrate this to our education system, we can make a big change in 5–10 years’.

4.1.5. Commitment—Act upon the Word

We constructed this theme out of discussions surrounding the lack of commitment towards a climate-oriented goal and profession, which poses a threat to pursuing sustainable urban climate actions (See Table 9).

Table 9.

Details of Theme 5.

- a.

- Commitment—from ‘document to practice’

Sri Lanka is a party to many international commitments to tackle climate change, such as the Kyoto Protocol. However, AC1 indicated that no effort is made to meet these commitments—‘we have nice set of documents, but nothing visible in practice’.

Further, PR2 and AC2 also indicated that checkpoints and assessments tend to exist only in documents and not in practice. PR2 said that ‘… the existing green building council rating focuses only on a rating system which has a minimum requirement, and once achieved, performance is not checked at the end…’.

While it is the responsibility of the relevant authorities to ensure the commitments are met, PR2 advocated global fairness as a consideration for policymakers to consider prior to undertaking such commitments, considering the country’s economic and social conditions.

- b.

- Professional ethics/public commitment/political will

A layman’s first point of contact with expert opinion is the professionals—planners, architects, designers, etc. AC1 stated that ‘if planners and architects consider their job at a more responsible and ethical angle, definitely these strategies be incorporated…, can be seen as an effective bottom up approach’. They also stated that professionals have the ultimate responsibility to advocate for urban climate action to the general public, investors and politicians.

‘Similarly, the public should also act responsibly’, said PR2. ‘When a fine imposed for littering the roads, the public obeyed; and once the implementation was stopped, they went back to their old habits’, providing an insight into the public mentality.

All interviewees strongly suggested political will as an important factor for successful UC action. PR2 stressed that it is again the professionals’ responsibility to convey the benefits in terms of financial benefits and advocate the benefits of urban climate actions.

4.1.6. Continuity—’Rome Was Not Built in a Day’

The theme of ‘continuity’ implies the notion of the continuous improvement and review of planning, policy, audits, and data in urban planning and governance (See Table 10).

Table 10.

Details of Theme 6.

- a.

- Policy continuity despite regime change

We constructed this subordinate theme with explicit notions indicating that political interference has an influence on genuine planning attempts. One participant noted that ‘There are government agencies such as Climate Change Secretariat, Sustainable Development Authority etc. to maintain climate commitments and actions. But these are discontinued with government changes and regime changes’.

Similarly, others also reflected that all genuine efforts of planners and policymakers go astray due to political interference and regime change.

- b.

- Audit: inception to completion and during use

Suggestions regarding the continuous monitoring of events in planning from inception to completion led to the generation of this subordinate theme.

When indicating effective means of regulating the built environment, AC1 said that ‘We can add climate checkpoints to enforce climate sensitive planning, but this again becomes only a permit—it will end up only in documents and not in practice. Hence, there must be an independent assessment, even during construction’. PR1 also resonated with this, saying that ‘There has to be a continuous audit system which monitors the construction from planning to completion’. They further indicated that the planning bodies lack the resources to undertake a successful audit.

Monitoring, evaluation, and reporting (MER) is a process that has been stressed for the fruitful outcomes of policy, plans, or projects [39] and has been proven to be an essential practice to ensure the project objectives while enabling flexibility [40].

- c.

- Periodic review

The subordinate theme, ‘Periodical review—planning’, implies that development plans should be continuously reviewed. There were repeated ideas emerging from the interviews; ‘we have an outdated plan’ and ‘we need a development plan that fits our context’ were heard a few times throughout the interview. As a planner and an administrator, AD1 insisted that the plans must be reviewed every 5–10 years and adopted according to the context; instead, the current development plans and regulations still cater to the ‘last decade’.

Both practitioners had similar concerns about adopting a development plan that caters to the ‘actual trend’. Other participants also implied that the land use method used in the current system must be re-examined; we discussed this under the theme ‘Specify’.

We combined all the interview scripts, ran a query for the 250 most frequently occurring words, and generated word art (Figure 3). The emphasis is clearly on the need for ‘awareness’ and ‘detailed plans’, further reinforcing the idea of social and political influences in urban climate actions.

Figure 3.

Most frequently occurring themes.

Throughout the interviews, we identified several barriers with regard to implementing an effective solution to urban warming. We categorised them as political, social, economic, and other barriers (Table 11).

Table 11.

Summary of barriers to climate action in Colombo.

Similarly, we also identified opportunities for the implementation of urban climate actions and categorised them according to the identified themes (Table 12).

Table 12.

Summary of opportunities for intervention.

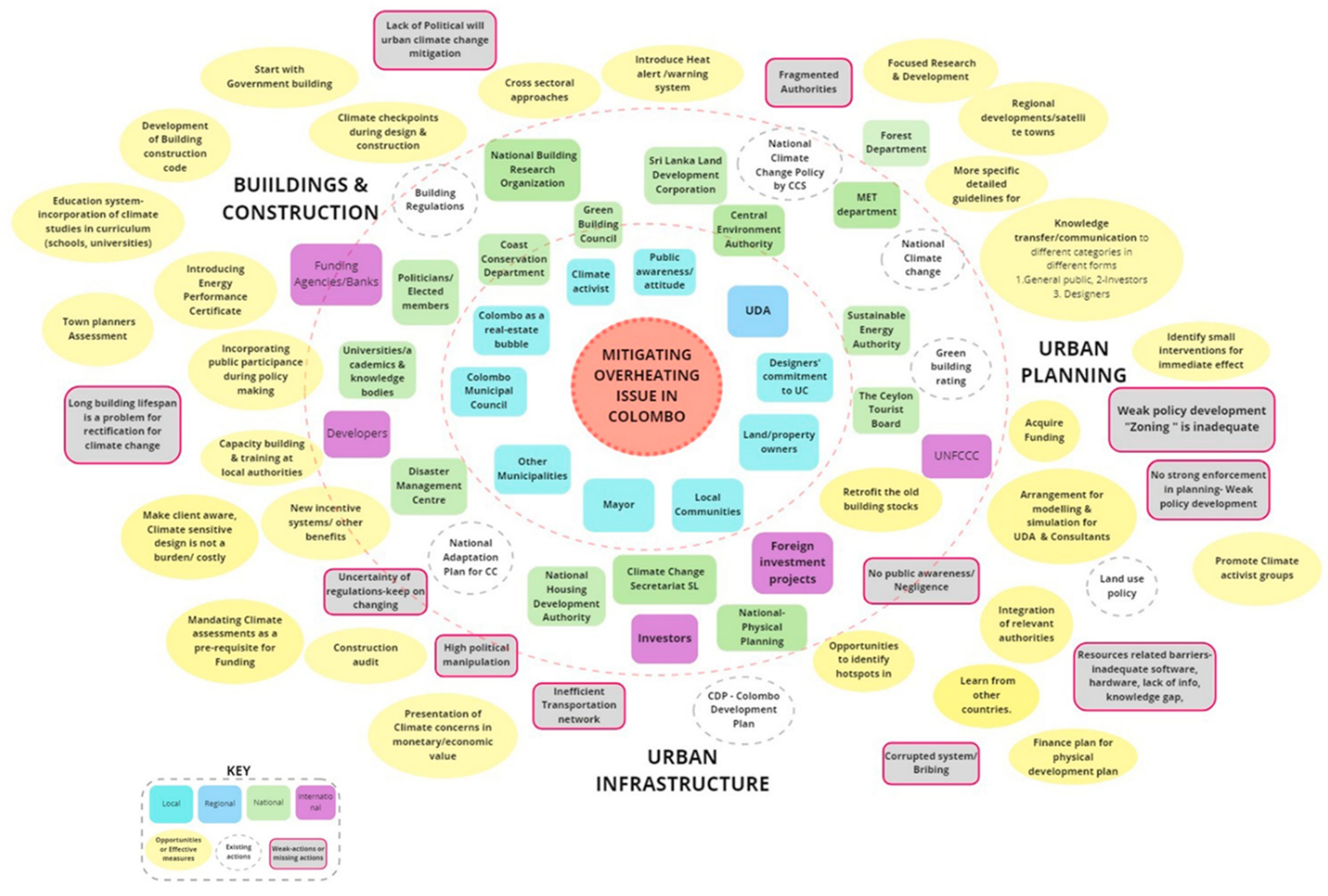

5. Discussion—Who Should Be Involved?

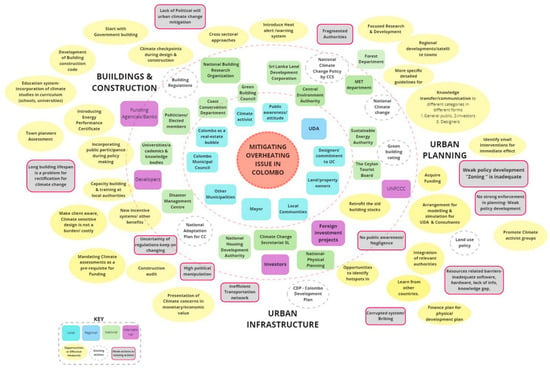

Urban warming is an issue that cannot be viewed in isolation but needs a holistic approach within the development agenda. Apart from the efforts of the epistemic community, a practical approach requires integrating all socio-political actors and institutions. The need for a proper network amongst stakeholders related to planning, infrastructure, and building construction was strongly emphasised during interviews.

While professionals play a guiding role in proactively guiding the public and exhorting the government, the public and politicians should also support their efforts. We could also investigate resolving the fragmentation of institutions as a primary objective while looking into encouraging policy initiatives gradually. Financial institutions and banks can also play an important role in regulating the built environment by stipulating financing conditions.

Figure 4 aims to capture the stakeholders that need to be involved (core—blue boxes and periphery—green boxes), identify agencies and individuals that could effect the necessary changes (purple boxes), and provide a set of exemplary policy prescriptions (yellow ovals). These are clustered around three scales of potential intervention—urban planning, infrastructure, and building scales. These scales are in line with the findings of [37,38]. The grey boxes present the many challenges and bottlenecks identified by our interviewees as major causes for urban climate inaction and by clustering actors and policies around the key challenges; we have attempted to identify specific pathways of implementation, key actions, and policies that are needed to enable these interventions and actors and agencies that should be tasked with the implementation. Further work is needed to flesh out specific implementation plans and feasibility analysis under different socio-political contexts. The examples provided in Figure 4 for the Colombo context, together with previous work by [37,38], could serve as a template for embedding urban climate knowledge in urban planning.

Figure 4.

Mind map of key urban climate stakeholders in Colombo.

6. Wider Implications

As the world continues to warm, cities (in particular developing cities) face twin problems. On the one hand, urban climate science remains under-represented in the assessment and mitigation of global climate change. On the other hand, existing knowledge of the urban climate is not well-integrated into sustainable urban development policy and planning. The case of heat resilience planning (or lack thereof) in Colombo, Sri Lanka, serves as a warning and a learning point for other developing cities. Urban overheating is already at the thresholds of tolerance (i.e., ‘extreme heat stress’) in many parts of the world [3], and this is also true in Sri Lanka [8]. While the need for embedding urban climate knowledge in the wider global climate science is ever more pressing, cities need to act now to enhance their sustainable survival to avoid placing unnecessary economic burdens on already economically stressed societies. Urban climate design strategies can result in improved microclimate, but this should be integrated with the socio-economic enhancement of urban dwellers (through actions to address underserved settlements, poverty alleviation, urban regeneration, etc.) and incorporating socio-political actors (planners, professionals, politicians, the general public, etc.). Specific implementation plans that explicitly address the barriers identified in the present work are needed, and their feasibility will depend on the local context.

‘How’ to achieve this needs more intense scrutiny, but we need to be mindful of context-specific scientific and sociological data. Urgent action is needed to arrest the worsening heat stress in cities. The local monitoring of climate change in the urban context is needed to inform new planning solutions that consider local climate improvement as a performance indicator for a better quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.S. and R.E.; methodology, S.S., E.A. and R.E.; software, S.S.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S.; resources, R.E.; data curation, S.S. and R.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, R.E. and E.A.; visualisation, S.S.; supervision, R.E. and E.A.; project administration, R.E. and E.A.; funding acquisition, R.E. and E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA), grant number 2017-1926 ‘Master of Urban Climate and Sustainability’.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance given by all interviewees who agreed to take part in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acronyms

| CCD | Coast Conservation Department |

| CCS | Climate Change Secretariat |

| CDP | Colombo Development Plan |

| CEA | Central Environmental Authority |

| CMC | Colombo Municipal Council |

| CMRSP | Colombo Metropolitan Regional Structure Plan |

| CTB | Ceylon Tourist Board |

| DMC | Disaster Management Committee |

| EPC | Energy performance certificate |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| IPCC | Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change |

| Megapolis | Western Regional Megapolis Development Agency |

| NBC | National Building Code |

| NBRO | National Building Research Organisation |

| NHDA | National Housing Development Authority |

| NPPD | National Physical Planning Department |

| SLLRDC | Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation |

| SLSEA | Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority |

| UDA | Urban Development Authority |

| UHI | Urban heat island |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UW | Urban warming |

References

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liao, W.; He, G.; Tett, S.F.B.; Yan, Z.; Zhai, P.; Feng, J.; Ma, W.; Huang, C.; et al. Anthropogenic emissions and urbanization increase risk of compound hot extremes in cities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, O.D.; van Aalst, M.K.; Birkmann, J.; Fordham, M.; McGregor, G.; Perez, R.; Pulwarty, R.S.; Schipper, E.L.F.; Sinh, B.T. Determinants of risk: Exposure and vulnerability. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Field, C.B., Barros, V., Stocker, T.F., Dahe, Q., Dokken, D.J., Ebi, K.L., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Plattner, G.-K., Allen, S.K., Eds.; A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Im, E.-S.; Pal, J.S.; Eltahir, E.A.B. Deadly heat waves projected in the densely populated agricultural regions of South Asia. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoli, G.; Fatichi, S.; Schläpfer, M.; Yu, K.; Crowther, T.W.; Meili, N.; Burlando, P.; Katul, G.G.; Bou-Zeid, E. Magnitude of urban heat islands largely explained by climate and population. Nature 2019, 573, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuholske, C.; Caylor, K.; Funk, C.; Verdin, A.; Sweeney, S.; Grace, K.; Peterson, P.; Evans, T. Global urban population exposure to extreme heat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2024792118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, R.; Kusaka, H.; Doan, Q.-V.; Cai, P.; He, H.; Luo, G.; Kuang, W.; Caluwaerts, S.; Duchêne, F.; Van Schaeybroek, B.; et al. The State-of-the-Art of Urban Climate Change Modeling and Observations. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulev, S.K.; Thorne, P.W.; Ahn, J.; Dentener, F.J.; Domingues, C.M.; Gerland, S.; Gong, D.; Kaufman, D.S.; Nnamchi, H.C.; Quaas, J.; et al. Changing state of the climate system. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 287–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simath, S.; Emmanuel, R. Urban thermal comfort trends in Sri Lanka: The increasing overheating problem and its potential mitigation. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 1865–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, K.; Kulkarni, S.P.; Azhar, G.S.; Mavalankar, D.; Jaiswal, A.; Connolly, M.; Nori-Sarma, A.; Rajiva, A.; Dutta, P.; Deol, B.; et al. Development and Implementation of South Asia’s First Heat-Health Action Plan in Ahmedabad (Gujarat, India). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3473–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO 2022. Extreme Heat Is a Silent Emergency, Global Heat Health Information Network. Available online: https://ghhin.org/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Emmanuel, R. A Hypothetical ‘Shadow Umbrella’ for Thermal Comfort Enhancement in the Equatorial Urban Outdoors. Arch. Sci. Rev. 1993, 36, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tablada, A.; De Troyer, F.; Blocken, B.; Carmeliet, J.; Verschure, H. On natural ventilation and thermal comfort in compact urban environments—The Old Havana case. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1943–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaid, A.; Bin Lamit, H.; Ossen, D.R.; Shahminan, R.N.R. Urban heat island and thermal comfort conditions at micro-climate scale in a tropical planned city. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, P.; Lim, K.C.; Jamei, E. Urban heat island and wind flow characteristics of a tropical city. Sol. Energy 2014, 107, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Cheng, V. Urban human thermal comfort in hot and humid Hong Kong. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S.; Tsikaloudaki, A.; Theodosiou, T. Analyzing the ENVI-met microclimate model’s performance and assessing cool materials and urban vegetation applications—A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu-Harbich, L.V.; Labaki, L.C.; Matzarakis, A. Effect of tree planting design and tree species on human thermal comfort in the tropics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, E.; Ossen, D.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Sandanayake, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Horan, B. Urban design parameters for heat mitigation in tropics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erell, E.; Pearlmutter, D.; Boneh, D.; Kutiel, P.B. Effect of high-albedo materials on pedestrian heat stress in urban street canyons. Urban Clim. 2014, 10, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarsini, R.; Hien, W.N.; David, C.K.W. Microclimatic modeling of the urban thermal environment of Singapore to mitigate urban heat island. Sol. Energy 2008, 82, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, R.; Fernando, H.J.S. Urban Heat Islands in Humid and Arid Climates: Role of Urban Form and Thermal Properties in Colombo, Sri Lanka and Phoenix, USA. Clim. Res. 2007, 34, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, A.; Kolokotroni, M. Impact of urban albedo on microclimate and thermal comfort over a heatwave event in London. In Proceedings of the Windsor 2020 11th Winsor Conference: Resilient Comfort, Windsor, UK, 16–19 April 2020; Proceedings. Roaf, S., Nicol, F., Finlayson, W., Eds.; 2020; pp. 566–578. Available online: https://windsorconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WC2020_Proceedings_small.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.-H.; Kaloush, K.E.; Dylla, H. Effect of pavement thermal properties on mitigating urban heat islands: A multi-scale modeling case study in Phoenix. Build. Environ. 2016, 108, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cabeza, V.P.; Alzate-Gaviria, S.; Diz-Mellado, E.; Rivera-Gomez, C.; Galan-Marin, C. Albedo influence on the microclimate and thermal comfort of courtyards under Mediterranean hot summer climate conditions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 81, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wei, K.; Guan, Z. Exploring the connection between morphological characteristic of built-up areas and surface heat islands based on MSPA. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1-4522-7572-7. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Ed.; s.l.:American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, J. A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis. Qual. Rep. 1995, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, P. The Integrated Ideal in Urban Governance-Compact City Strategies and the Case of Integrating Urban Planning, City Design and Transport Policy in London and Berlin. Ph.D. Thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thierauf, R.J. Knowledge Management Systems for Business; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, G.; Cleugh, H.; Emmanuel, R.; Endlicher, W.; Erell, E.; McGranahan, G.; Ng, E.; Nickson, A.; Rosenthal, J.; Steemer, K. Climate Information for Improved Planning and Management of Mega Cities (Needs Perspective). Procedia Environ. Sci. 2010, 1, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilaka, K. An Assessment of Urban Sprawl in Colombo District, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the Colombo, International Conference on the Humanities (ICH), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 21–22 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Antalyn, B.; Weerasinghe, V.P.A. Assessment of Urban Sprawl and Its Impacts on Rural Landmasses of Colombo District: A Study Based on Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Asia-Pac. J. Rural. Dev. 2020, 30, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, J.; Smith, G.; Benson, D.; Saunders, C. Politics and the Environment—From Theory to Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat, 2014. Planning for Climate Change—A Strategic Value Based Approach for Urban Planners, Nairobi: UN. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/planning-for-climate-change-guide-a-strategic-values-based-approach-for-urban-planners (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Agathangelidis, I.; Cartalis, C.; Santamouris, M. Integrating Urban Form, Function, and Energy Fluxes in a Heat Exposure Indicator in View of Intra-Urban Heat Island Assessment and Climate Change Adaptation. Climate 2019, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, E.; Anguelovski, I.; Carmin, J. Inclusive approaches to urban climate adaptation planning and implementation in the Global South. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, S.; Denniss, R. An Introduction to Australian Public policy—Theory and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- de Murieta, E.S.; Galarraga, I.; Olazabal, M. How well do climate adaptation policies align with risk-based approaches? An assessment framework for cities. Cities 2021, 109, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostermann, J.; van de Sandt, K.; Harley, M.; Hildén, M.; Leiter, T.; van Minnen, J.; Pieterse, N.; van Bree, L. Towards a framework to assess, compare and develop monitoring and evaluation of climate change adaptation in Europe. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2018, 23, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).