Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being in Embassy Architecture: Educational Approaches and Design Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context and Framework

- What are the challenges and opportunities in enhancing cultural sensitivity and social well-being in embassy architecture?

- What are the main insights for educational approaches in design studios, and which design strategies can be applied?

1.2. Paper Outline

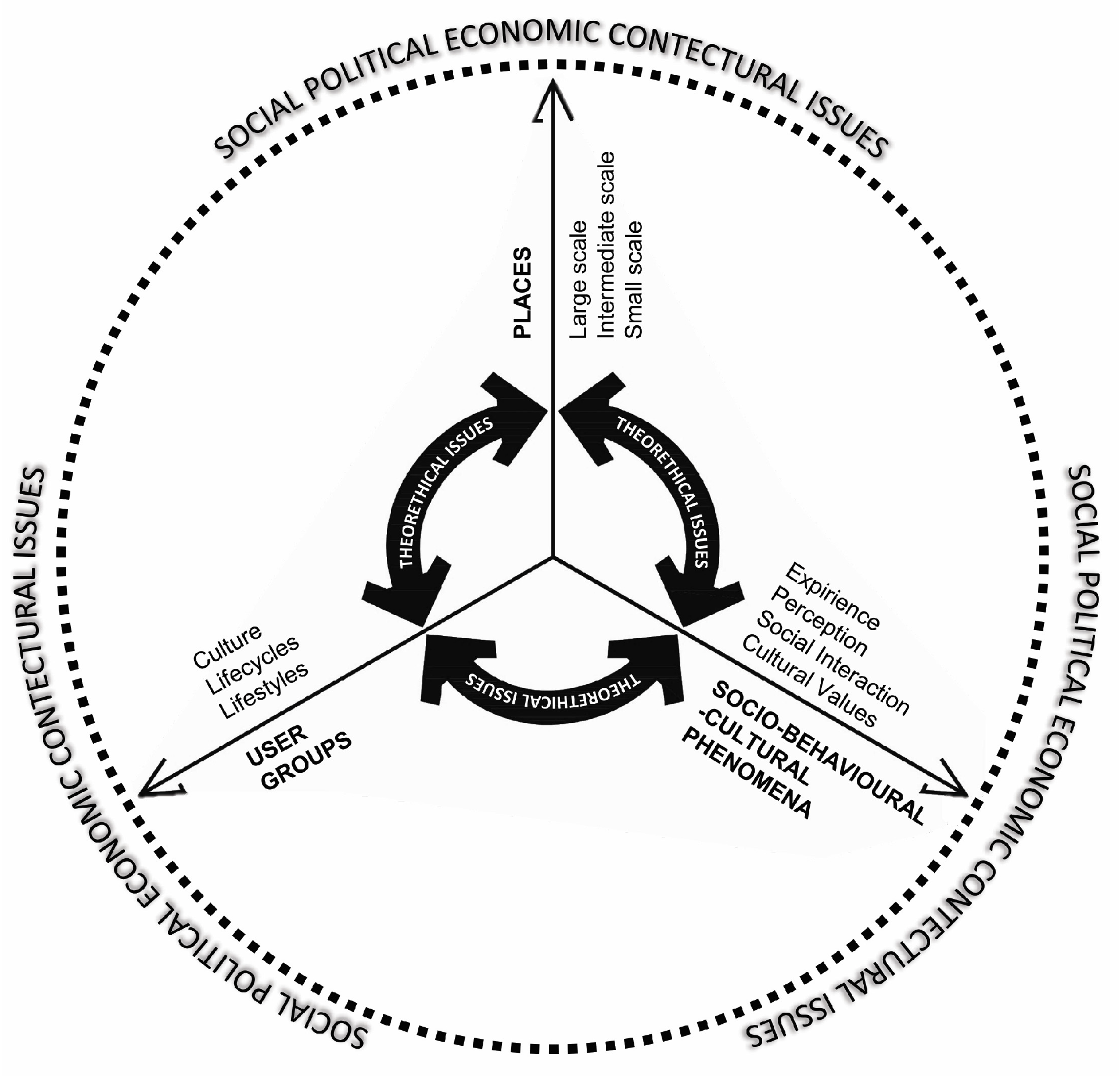

- Theoretical Background: This section broadly discusses cultural sustainability, emphasizing cultural sensitivity and social well-being. It discusses implications for the built environment from a framework of environment–behavior studies, conceptualizing relationships between users, architecture, and the surrounding environment.

- Methodological Framework: This section consists of an explanation of the research methodology.

- Findings and Discussion: This section examines the key research insights derived from the research. It explores challenges and notable points of interest identified in the results of the particular assignment given to master’s students of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Belgrade. Limitations and future challenges are discussed, offering insight into researchable scenarios for other related theoretical and practical investigations.

- Conclusion: The concluding remarks emphasize the importance of enhancing cultural sensitivity and social well-being within architectural education and embassy design practice. The opportunities and threats are highlighted.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Cultural Sustainability: Current Perspectives and Challenges

2.1.1. Environment–Behavior Studies as a Framework for Culturally Sustainable Architecture

2.1.2. Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being as Design Drivers

2.2. Diplomatic Architecture: From Introversion to Integration

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Research Design

3.1.1. First Phase—Research by Design of Embassy Architecture

- (1)

- In the Investigation Phase, outputs include contextual analysis and understanding of national identity representation. This involves examining examples of diplomatic architecture to identify patterns and understand how architectural elements express cultural, historical, and social identities to understand its operational dynamics within various socio-political contexts.

- (2)

- The Problem Definition Phase produces strategic research plans and actionable design briefs. These outline research directions, objectives, and methodologies, serving as a roadmap for achieving goals related to cultural sustainability. Design briefs translate research findings into specific design challenges. Following the investigative phase, students define specific problems and set partial assignments and goals within an overall program [12]. This phase is crucial as it translates theoretical insights into actionable design briefs, setting the stage for innovative architectural interventions [56]. By emphasizing strategic planning, students learn to conceptualize and spatially interpret imported cultural, social, and spatial identities in sustainable environments.

- (3)

- The Proposals Phase generates design proposals and conceptual spatial layouts. Initial solutions are presented as sketches, drawings, or models, refined iteratively through feedback. Conceptual layouts visualize designs in context, aiding in understanding their spatial implications. The concrete spatial solutions respond to the defined program [12]. This experimental phase allows students to explore innovative design solutions reflecting the sending country’s cultural identities. Through iterative design processes, students create proposals that challenge traditional notions of diplomatic architecture, often characterized by insularity and fortification. Instead, they design spaces that emphasize transparency, openness, and integration within the urban fabric. This phase underscores the critical role of creative experimentation in architectural design, allowing students to push the boundaries of conventional practice.

- (4)

- The Rationalization Phase, as the final phase, involves the rationalization of design proposals, where students articulate the theoretical underpinnings of their designs and argue for their validity [12]. They align theoretical concepts with practical design solutions incorporating principles of cultural sustainability. This phase ensures that the designs are aesthetically and functionally sound and backed up by comprehensive theoretical analysis. The iterative nature of this phase allows for continuous improvement, reflecting the dynamic interplay between architecture, socio-political contexts, and students’ spatial proclivities.

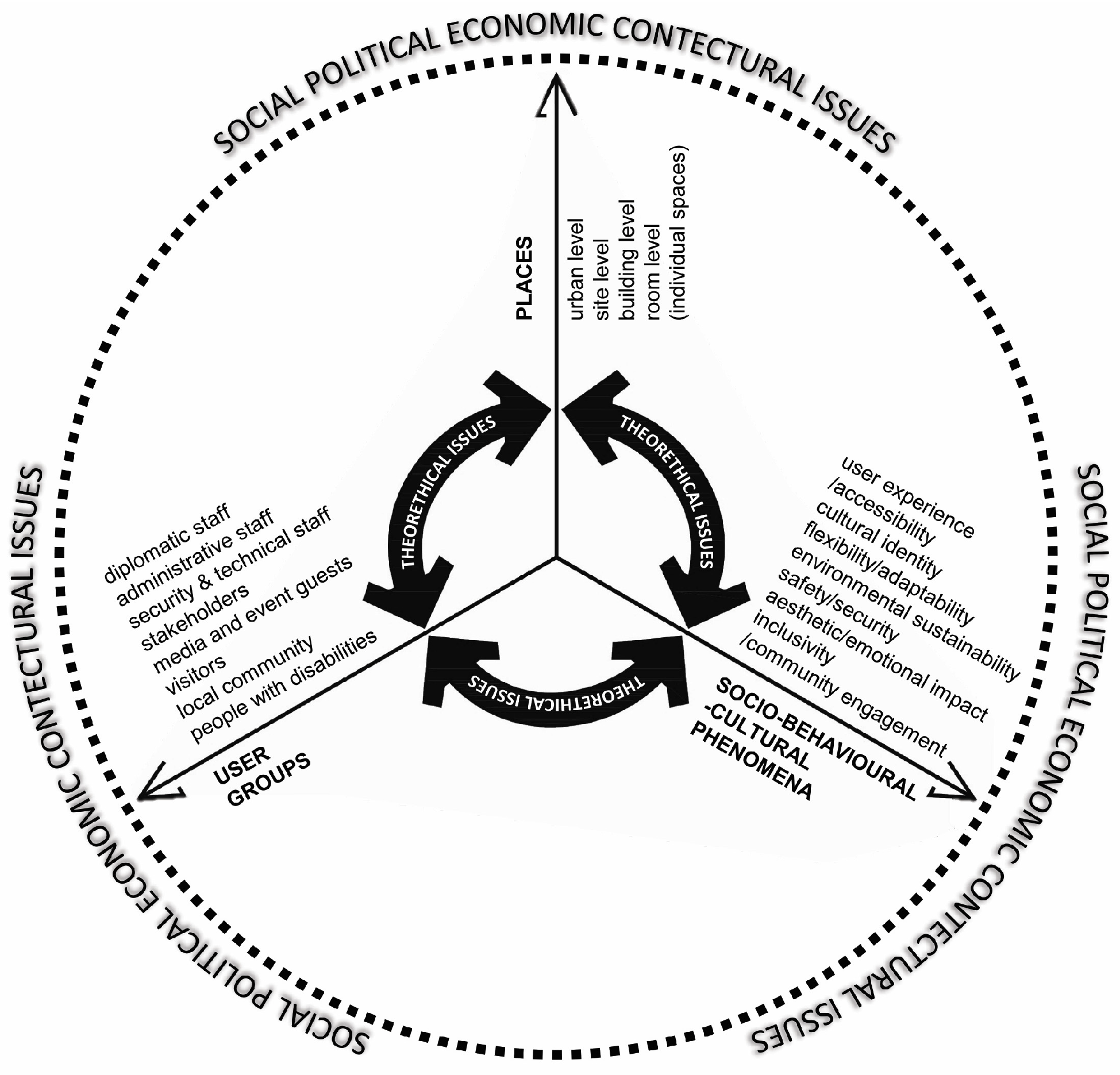

3.1.2. Second Phase—Qualitative Data Analysis of Design Proposals and Strategies

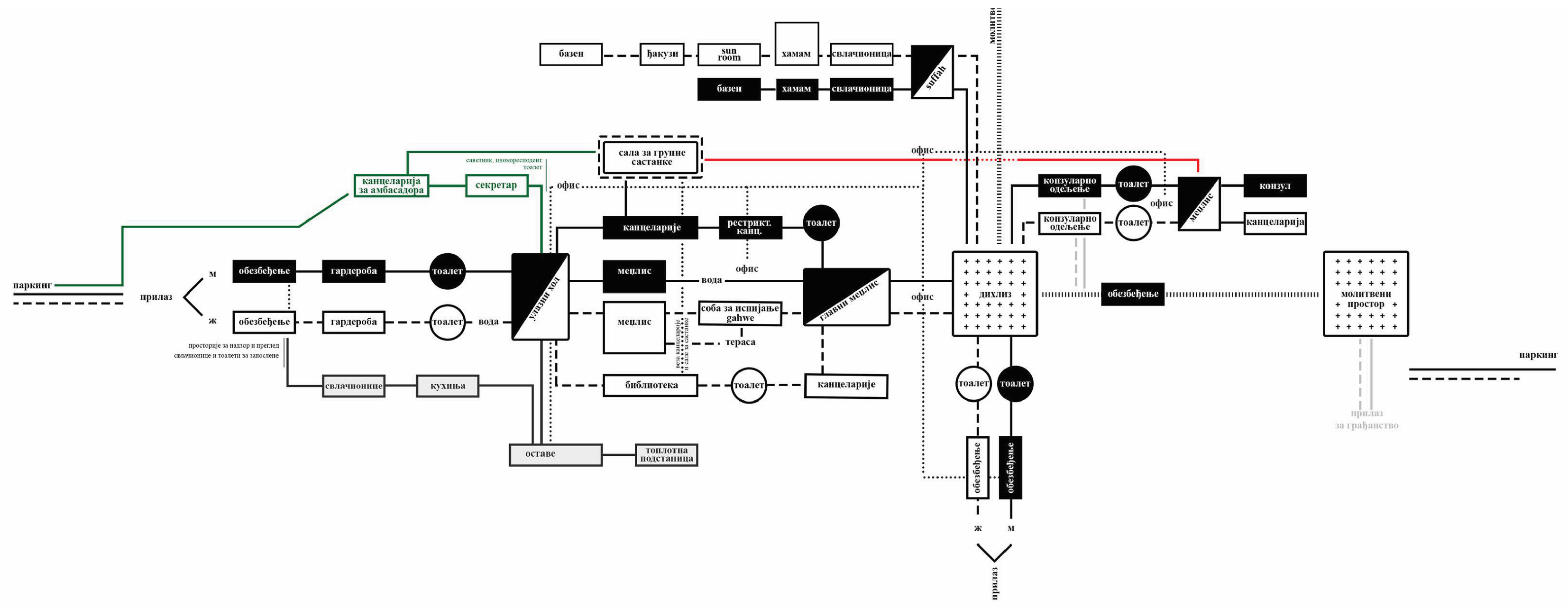

- The users’ group perspective: The specific user groups were defined to ensure the design solution is inclusive and responsive to the diverse needs of a broader range of stakeholders (diplomatic staff, administrative staff, security and technical staff, stakeholders, media and event guests, visitors, local community, people with disabilities).

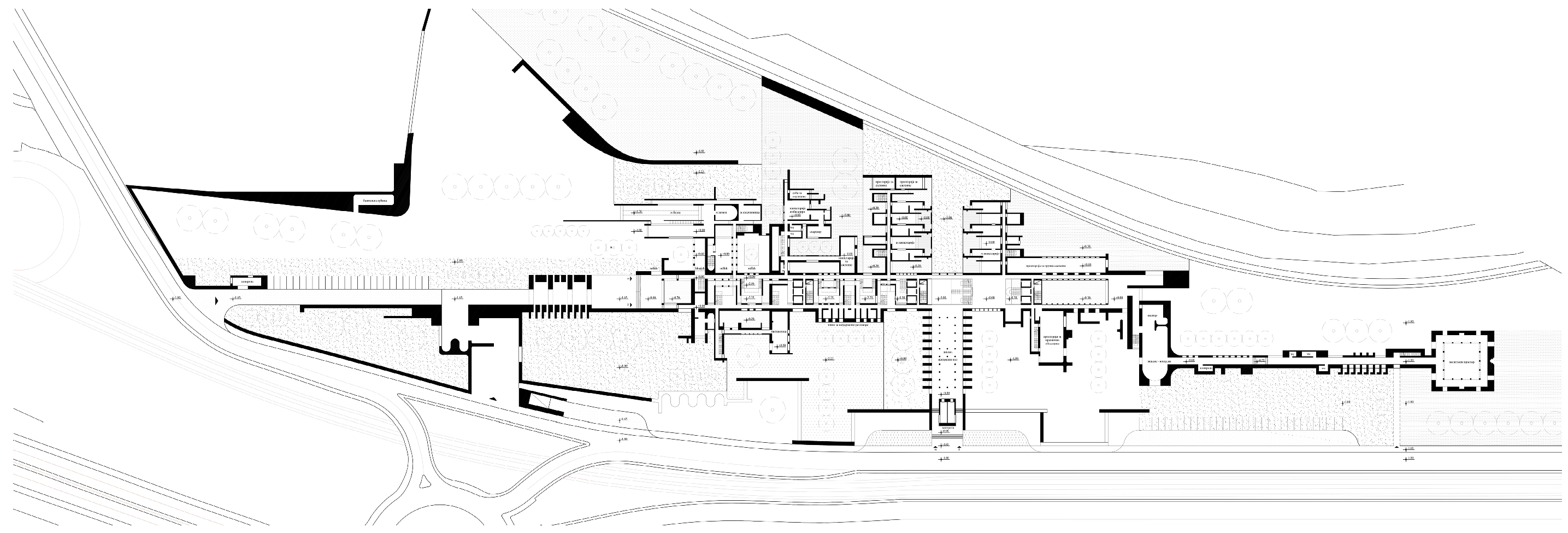

- The spatial-level perspective: The investigation examined the design intervention at multiple scales, from the room scale to the neighborhood scale, to ensure the cultural and social impacts were considered holistically (urban level, site level, building level, room level (individual spaces)).

- The socio-behavioral–cultural perspective: The research explored how cultural practices, traditions, and values could be incorporated into the design to enhance the space’s overall cultural significance and meaning (user experience and accessibility, cultural identity, flexibility and adaptability, environmental sustainability, safety and security, aesthetic and emotional impact, inclusivity, and community engagement).

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of Design Proposals within the Framework of EBS

4.1.1. The Users’ Group Perspective

4.1.2. The Spatial-Level Perspective

4.1.3. The Socio-Behavioral–Cultural Perspective

4.2. Identification of Design Strategies for Enhancing Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being

4.2.1. Protected Cultural Integration Design Strategy

4.2.2. Open Cultural Connectivity Design Strategy

- Geyser: Emphasizes the power of water, using sounds and the contrast between activation and silence, with ample light;

- Minerals: Represents science, using underground ambiences, solitude, and tactile focus, with darker spaces;

- Ice: Continues solitude and silence, focusing on the expanse and clarity, with fresh air and simplicity;

- Energy: Introduces darkness and noise, with pulsating, vibrating ambiences;

- Volcano: Presents solid, dry, heavy spaces with occasional strong light bursts;

- Glacier: Combines heaviness and cold with bright illumination, creating a pressurized, illuminated ice cave.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings Linked to Research Questions

- What are the challenges and opportunities in enhancing cultural sensitivity and social well-being in embassy architecture?

- What are the main insights for educational approaches in the design studio, and which design strategies can be applied?

5.2. Research Limitations and Obstacles

5.3. Moving Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schiano-Phan, R.; Soares Gonçalves, J.C. Sustainability in Architectural Education—Editorial. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić Trajković, J.; Milovanović, A.; Nikezić, A. Reprogramming Modernist Heritage: Enhancing Social Wellbeing by Value-Based Programming Approach in Architectural Design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Directorate-General for Education Youth Sport Culture. Stormy Times. Nature and Humans: Cultural Courage for Change: 11 Messages for and from Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Final Declaration of the UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Policies and Sustainable Development—MONDIACULT 2022; Mexico City, Mexico. 2022. Catalog Number 0000382887. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000382887.locale=en (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- European Commission Directorate-General for Communication. Towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030: Reflection Paper; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2019-02/rp_sustainable_europe_30-01_en_web.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Nikezic, A. Enhancing Biocultural Diversity of Wild Urban Woodland through Research-Based Architectural Design: Case Study-War Island in Belgrade, Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, A.; Milovanović, A.; Milojević, M.P.; Zorić, A.; Pešić, M.; Ristić Trajković, J.; Nikezić, A.; Djokić, V. Developing Methodological Framework for Addressing Sustainability and Heritage in Architectural Higher Education—Insights from HERSUS Project. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learning for Sustainability in Europe. Building Competences and Supporting Teachers and Schools: Eurydice Report; 2024. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/81397 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Asojo, A.O. A model for integrating culture–based issues in creative thinking and problem solving in design studios. J. Inter. Des. 2001, 27, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, I. Soft Power Architecture: Mechanisms, Manifestations and Spatial Consequences of Embassy Buildings and Exported Ideologies. Ph.D. Thesis, Keio University, Minato, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic, I. The Architecture of Post Diplomacy: Construction Process of the Japanese Embassy in Belgrade [Serbia]. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference and Exhibition: On Architecture: Facing the Future, Belgrade, Serbia, 7–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hauberg, J. Research by design: A research strategy. Rev. Lusófona Archit. E Educ. 2011, 5, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T.S. Definitions and frameworks for environmental sustainability in higher education. High. Educ. Policy 2002, 15, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djokić, V.; Ristić Trajković, J.; Krstić, V. An Environmental Critique: Impact of Socialist Ideology on the Ecological and Cultural Sensitivity of Belgrade’s Large-Scale Residential Settlements. Sustainability 2016, 8, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić Trajković, J.; Krstić, V.; Milovanović, A.; Calheiros, C.S.C.; Ćujić, M.; Karanac, M.; Kazak, J.K.; Di Lonardo, S.; Pineda-Martos, R.; Garcia Mateo, M.C.; et al. Moving Towards a Holistic Approach to Circular Cities: Obstacles and Perspectives for Implementation of Nature-Based Solutions in Europe. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED, S.W.S. World commission on environment and development. Our Common Future 1987, 17, 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, S.; Turner, M. Understanding Environmental Issues; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, S. Mapping sustainable development as a contested concept. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A. Pillars, Bottom Lines, Capitals and Sustainability: A Critical Review of the Discourses; Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, R.L. Socio-cultural sustainability of housing: A conceptual exploration. Hous. Theory Soc. 2004, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland, I. Cultural sustainability: Industrialism, placelessness and the re-animation of place. Ethics Place Environ. (Ethics Place Environ. (Merged Philos. Geogr.) 2008, 11, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, D. What is intercultural sustainability? A first exploration of linkages between culture and sustainability in intercultural research. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 9, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van den Bosch, A. Professional artists in Vietnam: Intellectual property rights, economic and cultural sustainability. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2009, 39, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-García, M.J.; Kubus, R.; Argüelles-Bustillo, R.; García-García, M.J. A new European Bauhaus for a culture of transversality and sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirror, H. Lessons Learned from the Past: Tracing Sustainable Strategies in the Architecture of Al-Ula Heritage Village. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic Trajkovic, J. The Application of Environment-Behavior Theories in Architectural Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Architecture, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B. A Tale of Three Cities: Or The Glocalization of City Management; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I. Privacy regulation: Culturally universal or culturally specific? J. Soc. Issues 1977, 33, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.T. Toward Environment-Behavior Theories of the Middle Range. In Toward the Integration of Theory, Methods, Research, and Utilization; Moore, G.T., Marans, R.W., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: Architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Volume 5019. [Google Scholar]

- Iriye, A. Cultural Internationalism and World Order; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Poutignat, P.; Streiff-Fénart, J. L’ancrage social des différences culturelles. L’apport des théories de l’ethnicité. Diogène, 2017; 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, T.H. Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Golubović, Z. Ja i Drugi: Antropološka Istraživanja Individualnog i Kolektivnog Identiteta; Republika: Beograd, Serbia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Korez-Vide, R. Enforcement of Soft Power and Cultural Diplomacy in Contemporary International Relations: The Case of Slovenia and Estonia (Presadzovanie Mäkkej Sily A Kultúrnej Diplomacie V Súčasných Medzinárodných Vzťahoch: Prípad Slovinska A Estónska). Medzinar. Vzt. (J. Int. Relat.) 2014, 12, 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- Anholt, S. Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; pp. XIII, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, J.S. Public Diplomacy and Soft Power. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2008, 616, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. Research and Application of the Sustainable Architectural Design Theory. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2021), Moscow, Russia, 9–10 March 2021; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott, P.; Keys, C. Redefining architecture to accommodate cultural difference: Designing for cultural sustainability. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2015, 58, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey Lee, M.K. Social Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, I.; Tomić, D.V. Soft power architecture: (Un)intentional and incidental in culture relations policies. Arhit. I Urban. 2019, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.C. The Architecture of Diplomacy: Heyday of the United States Embassy-Building Program, 1954–1960. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 1990, 49, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.C. The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies; Princeton Architectural Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Coaffee, J. Rings of steel, rings of concrete and rings of confidence: Designing out terrorism in central London pre and post September 11th. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, N.J. Public Diplomacy: Lessons from the Past; Figueroa Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The American Institute of Architects. Design for Diplomacy. New Embassies for the 21st Century; The American Institute of Architects: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, K. Does Architectural “Excellence” Put Embassies at Risk? Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/527363/does-architectural-excellence-put-embassies-at-risk (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Pombo, F.; Heynen, H. Jules Wabbes and the Modern Design of American Embassies. Interiors 2014, 5, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeyer, B.; Floré, F.; Morel, A.-F. Architecture as Diplomatic Instrument? The Multi-Layered Meaning of the Belgian Embassy in New Delhi (1947–83). Archit. Hist. 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezabitowska, E.D. Research Methods and Techniques in Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, M.R.; Tamke, M. Narratives of Making: Thinking practice led research in architecture. In Proceedings of the Communicating (by) Design 2009, Belgium, Bruxelles, 15–17 April 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mugerauer, R. Interpreting Environments: Tradition, Deconstruction, Hermeneutics; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Gazzeh, T. Privacy as the Basis of Architectural Planning in the Islamic Culture of Saudi Arabia. Archit. Behav. J. 1995, 11, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, H.C. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study; Federal Research Division Library of Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Alnaim, M.M. Understanding the traditional Saudi built environment: The phenomenon of dynamic core concept and forms. World J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 292–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ban, A.Z. Architecture and Cultural Identity in the Traditional Homes of Jeddah; University of Colorado at Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ban, A.Z. Hijazi house: Gendered space and cultural relations. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2020, 197, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bahammam, A.S. Architectural Patterns of Privacy in Saudi Arabian Housing. Master’s Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Radwan, A. The Mosque as a public space in the Islamic City-An Analytical study of Architectural & Urban design of contemporary examples. J. Archit. Arts Humanist. Sci. 2020, 6, 18. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Mohannadi, A.; Furlan, R.; Grosvald, M. Women’s spaces in the vernacular Qatari courtyard house: How privacy and gendered spatial segregation shape architectural identity. Open House Int. 2023, 48, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslund, K. Iceland Imagined: Nature, Culture, and Storytelling in the North Atlantic; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, E. A Fusion of Nature and Technology?: Icelandic Identity, Activism, and the Art of Björk. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kropf, K. The Handbook of Urban Morphology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Input | Activities | Output | Transition Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investigation | Existing examples of diplomatic architecture | Analysis, criticism, problem formulation | Contextual analysis, understanding of national identity representation | Guided Research by Design methodologies |

| Problem Definition | Research insights, contextual analysis | Defining specific problems, setting assignments and goals | Strategic research plans, actionable design briefs | Strategic planning, conceptualization |

| Proposals | Strategic plans, theoretical insights | Developing spatial solutions, iterative design processes | Design proposals, conceptual spatial layouts | Creative experimentation, iterative design |

| Rationalization | Design proposals, feedback | Articulation of theoretical underpinnings, testing, and refining designs | Refined design proposals, comprehensive theoretical analysis | Continuous improvement, theoretical-practical alignment |

| Criteria | Excellent (+++) | Satisfactory (++) | Needs Improvement (+) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Framework | Comprehensive, well-argued, integrates diverse sources | Adequate, but lacks depth in some areas | Incomplete or poorly argued |

| Contextual Analysis | Insightful, nuanced understanding of socio-political contexts | Adequate understanding with minor gaps | Superficial or incorrect analysis |

| Design Innovation | Highly creative, challenges traditional notions | Creative but somewhat conventional | Lacks innovation, follows traditional paths |

| Practical Relevance | Highly applicable, well-integrated into real-world scenarios | Mostly applicable with some gaps | Lacks practical relevance |

| Design Solution | Theoretical Framework | Contextual Analysis | Design Innovation | Practical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

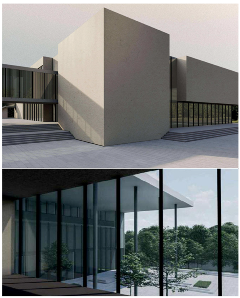

Design Solution 1—Embassy of Spain  | ++ | +++ | + | ++ |

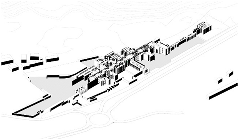

Design Solution 2—Embassy and Cultural Center of Mexico  | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

Design Solution 3—Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany  | + | ++ | + | ++ |

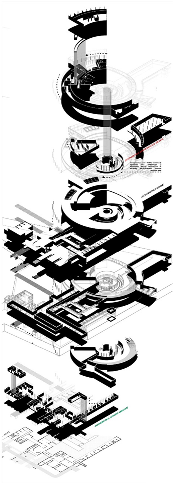

Design Solution 4—Embassy of Japan  | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

Design Solution 5—Embassy and Cultural Center Ireland  | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

Design Solution 6—Embassy of the United States of America  | + | ++ | +++ | ++ |

Design Solution 7—Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt  | + | + | + | + |

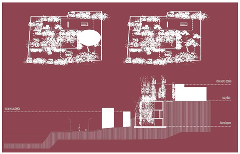

Design Solution 8—Embassy of Saudi Arabia  | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Design Solution | The Users’ Group Perspective Involved in Project Design | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diplomatic Staff | Administrative Staff | Security & Technical Staff | Stakeholders | Media and Event Guests | Visitors | Local Community | People with Disabilities | |

| Design Solution 1 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ◊ | ♦ |

| Design Solution 2 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ |

| Design Solution 3 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ◊ | ◊ | ♦ |

| Design Solution 4 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ |

| Design Solution 5 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ |

| Design Solution 6 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ |

| Design Solution 7 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ◊ | ◊ | ◊ | ◊ |

| Design Solution 8 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ |

| Student Name | The Spatial-Level Perspective | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Level | Site Level | Building Level | Room Level (Individual Spaces) | |

| Design Solution 1 | Open, green, and public spaces are well integrated. However, an intense analysis of how the design integrates into the city landscape and consideration of public transportation access is also needed. | Though parking solutions are weak, the site analysis is thorough, carefully focusing on topography and existing structure. The site features, such as elevation and view corridors, are well utilized. | The building design is innovative and functional, but it doesn’t adequately consider energy use. It incorporates green spaces well, creating a strong connection between indoors and outdoors. | Excellent room design offers flexibility and comfort for various user needs. Individual spaces are well-connected to the outdoors, with plenty of access to natural light and views of green spaces. |

| Design Solution 2 | Excellent urban integration, with well-connected open areas that blend seamlessly with the city’s public, and a clear vision of the building’s role within the urban fabric. | The natural landscape is well-used, but the green spaces are not fully integrated with the building’s functions. | The building design is innovative but doesn’t adequately consider energy use and sustainability features. The building structure is well-considered, with a strong balance of form and function. | A functional room layout could benefit from a more thoughtful interior design that enhances user experience. There is a good balance between private and communal spaces, but some individual spaces remain underdeveloped. |

| Design Solution 3 | The design does not adequately address open spaces and lacks opportunities for urban greening. It successfully aligns with the city’s character, but more thought is needed on the urban environment. | Satisfactory consideration of site conditions, but the building layout doesn’t fully utilize the natural landscape. The site plan is well-structured. | Functional layout, but misses opportunities to optimize natural light. It has a good building composition but lacks thought for how users will navigate complex spaces. | Room design is basic and utilitarian, failing to inspire or promote user engagement. |

| Design Solution 4 | Excellent attention to the city’s cultural and historical context, but some oversights in mobility infrastructure planning. A clear vision of the building’s role within the urban fabric. | Good utilization of site features such as elevation and view corridors. Green spaces are well-incorporated into the site, offering natural buffers and areas for public use. | The building’s innovative design and functional layout promote aesthetics and functionality. Green spaces thoughtfully woven into the design promote aesthetics and functionality. | The room design offers flexibility and comfort for a variety of user needs. It strikes a good balance between private and public spaces. |

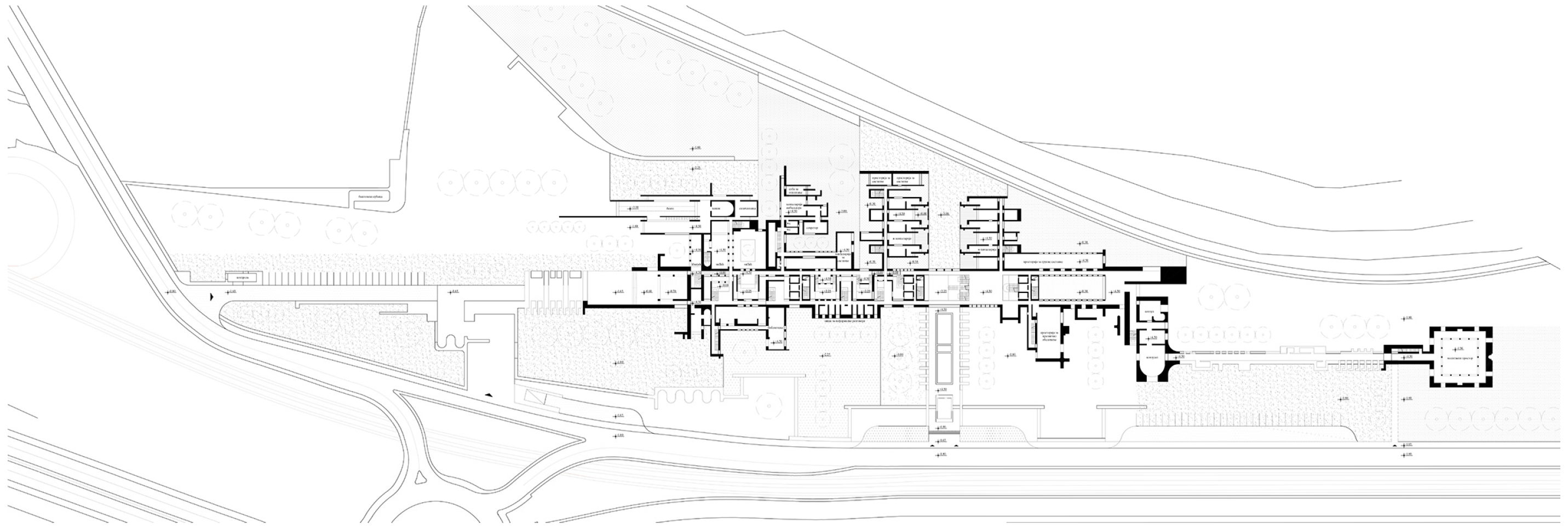

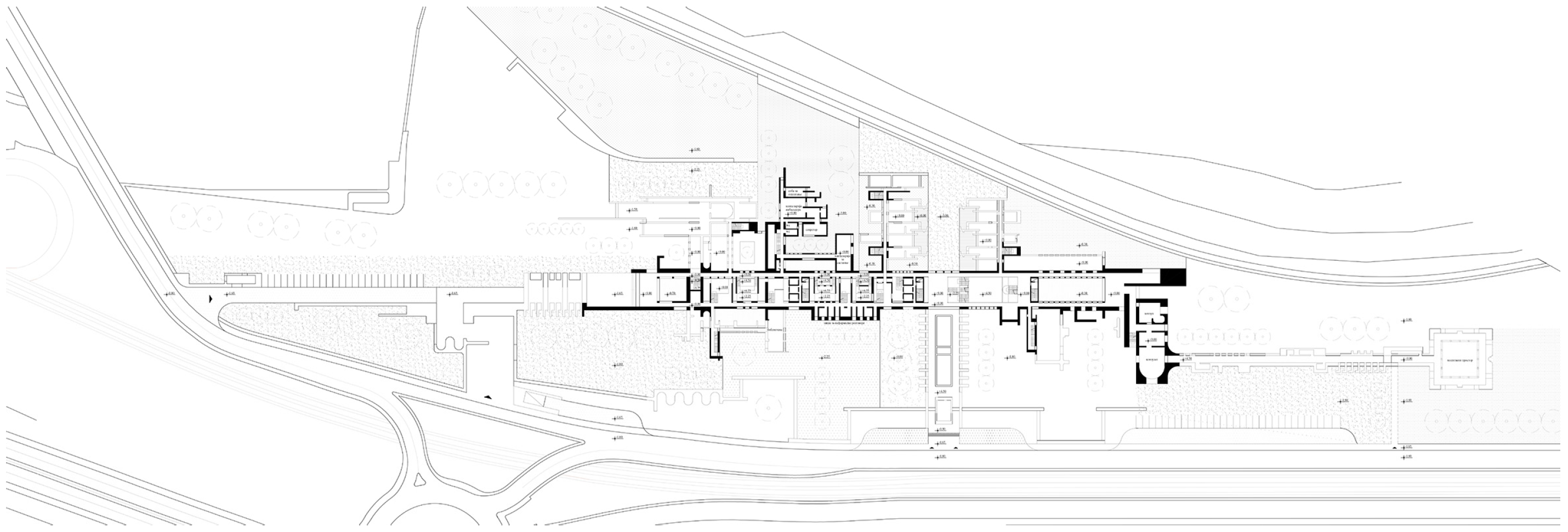

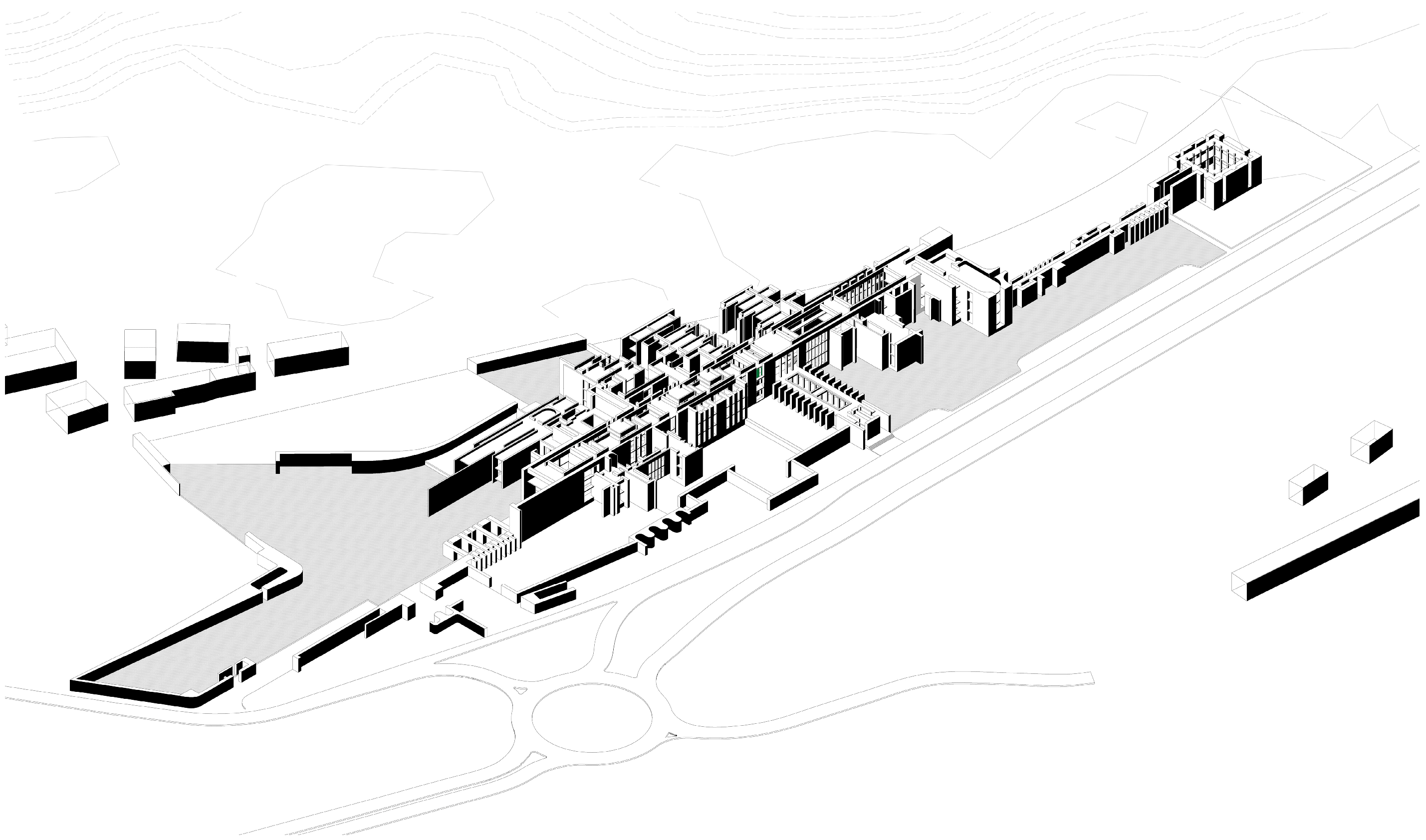

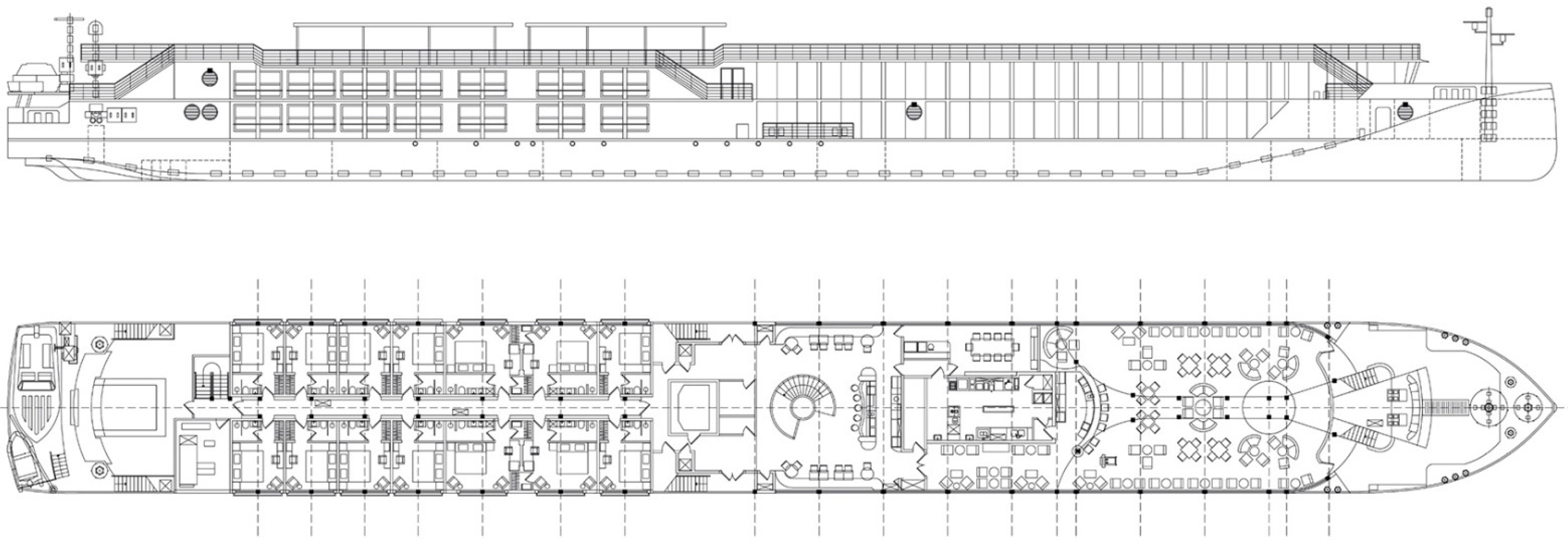

| Design Solution 5 | Innovative design that enhances ephemeral aspects of the project. Outstanding attention to the city’s cultural and historical context. | The site design integrates well with existing buildings and infrastructure. It successfully maximizes site potential through public access and makes good use of the natural landscape by the riverside. | Separating the building into two artifacts, one solid restoration of an old industrial building and another ephemeral floating structure project, makes an outstanding basis for research. | A good balance between indoor spaces and outdoor access creates a harmonious flow between rooms and green/blue areas. |

| Design Solution 6 | A centrally located urban site was selected. It is well-connected to the city’s life, offering excellent accessibility and integration with the surrounding urban fabric. | The site was designed so that its boundaries seamlessly blend with the surrounding environment, and public spaces are well-integrated and easily accessible. | The design’s functional organization is excellent and fully aligned with the security requirements, ensuring that the space operates efficiently while maintaining high safety standards. | Each room has been given adequate attention within the overall plan, with all functional standards being met, ensuring that the spaces are practical and well-integrated into the design. |

| Design Solution 7 | A central urban location was chosen, offering excellent connections to the city’s heritage and green/blue zones. However, the design has not adequately utilized the site’s full potential. | The site’s topography has not been adequately utilized, and mobility within and around it has not been sufficiently analyzed. | The design predominantly emphasized aesthetic form, while the functional connections between spaces were primarily overlooked. | Individual spaces are too isolated from the outdoors, lacking views or access to green areas. |

| Design Solution 8 | The site is connected to its surroundings through open and green spaces, where boundaries exist but are not rigid or emphasized. Instead, they are appropriately adjusted to blend with the environment. | The plot’s organization is exceptional, with well-thought-out access points and mobility pathways that make the design solution easy to understand and navigate. | The organization of the building is highly complex, yet it has been functionally resolved excellently, allowing for smooth movement throughout and ensuring that all spaces receive adequate sunlight. | Well-considered room designs that offer comfort and practicality. The individual rooms have been specifically designed to cater to the defined user groups, ensuring that each space meets its intended occupants’ unique needs and requirements. |

| Design Solution | The Cultural Phenomenon Perspective | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience/Accessibility | Flexibility/Adaptability | Environmental Sustainability | Safety/Security | Aesthetic/Emotional Impact | Inclusivity | Community Engagement | |

| Design Solution 1 | The design offers good accessibility with clearly defined pathways and entrances. | The spaces are flexible enough to be reconfigured based on different functions. Adaptability in long-term use is limited. | Sustainability measures are present but not fully integrated into the building’s core functions. | Security features are well-planned, with controlled access points. | The aesthetic choices create a serene and calming atmosphere. | The design is inclusive, considering a wide range of user needs. | The design encourages community engagement through open public spaces. |

| Design Solution 2 | The design excels in creating an immersive experience, but some accessibility features are underdeveloped. | Flexibility is a strong point, with adaptable interior layouts. | The project lacks innovative approaches to environmental design. | Safety is a concern, as some escape routes are unclear. | The design is visually captivating and fosters a strong emotional response. | Inclusivity is a highlight, with spaces that cater to various physical abilities. | Multifunctional areas support community engagement. |

| Design Solution 3 | The design is highly accessible, with intuitive paths and clear signage. However, better use of space could enrich the overall experience. | The design includes flexible areas that can be used for multiple purposes, but the exterior lacks adaptability. | Sustainability is minimally addressed, with only basic energy-saving measures. | The design prioritizes security without compromising aesthetics. | More cohesion between spaces would strengthen aesthetic impact. | The project promotes inclusivity with well-designed spaces for different user groups. | Community engagement is minimal, with few spaces designed for public use. |

| Design Solution 4 | Experience is engaging, with attention to detail in how users interact with different spaces. | The design’s adaptability is minimal, with little room for changes or reconfiguration. It is rigid in its current form. | Sustainability is well-considered, with efficient energy use and green spaces. | Security is robust, with well-placed surveillance and clear escape routes. | The design is visually appealing but lacks emotional warmth. | The project promotes inclusivity with well-designed spaces for different user groups. | Community interaction is considered but not fully realized. The spaces feel isolated from the broader social environment. |

| Design Solution 5 | The design is highly accessible, with intuitive paths and clear signage. | The design is fluid and temporary. This approach allows for flexibility and adaptability. | Environmental concerns are well-integrated into the design, with good use of passive heating and cooling. | Safety protocols are well integrated into the design. | The aesthetic choices are both beautiful and functional, creating an emotional connection with the users. | Inclusivity is well-integrated into the design, though more attention could be given to sensory disabilities and accessibility. | The project actively encourages community involvement, with spaces designed for events and gatherings. |

| Design Solution 6 | Accessibility is a strength in this design, with thoughtful consideration for disabled users. | While the indoor spaces are adaptable, the design does not easily support future changes. | Sustainability is well-considered, with efficient energy use and green spaces. | The project strongly focuses on safety, with clear emergency exits and well-placed security systems. | The space’s aesthetic impact is strong, creating an inviting atmosphere. However, the emotional connection to it feels distant. | Inclusivity is addressed, but certain user groups feel overlooked. | The design fosters community interaction through shared spaces. |

| Design Solution 7 | Access points are well-positioned, but the overall user experience feels disconnected from the environment. | Adaptability is minimal, with little room for changes or reconfiguration. | Environmental sustainability is a weak point in this project. | Safety and security have been overlooked in favor of aesthetics. | Aesthetic appeal is minimal, with a utilitarian focus. | Some areas need better accessibility features. | Community interaction is considered but not fully realized. |

| Design Solution 8 | The design balances accessibility and user experience well. | Highly adaptable design that allows for easy modifications over time. | Strong focus on sustainability, using renewable energy and green spaces effectively. | The project strongly focuses on safety, but some entry points need better control. | This harmony between the design and natural elements enhances the overall experience for users. | The design is highly inclusive and assessable, accommodating various user needs. | There is little attention to community engagement in this design. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krstić, V.; Filipović, I.; Ristić Trajković, J. Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being in Embassy Architecture: Educational Approaches and Design Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208880

Krstić V, Filipović I, Ristić Trajković J. Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being in Embassy Architecture: Educational Approaches and Design Strategies. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208880

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrstić, Verica, Ivan Filipović, and Jelena Ristić Trajković. 2024. "Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being in Embassy Architecture: Educational Approaches and Design Strategies" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208880

APA StyleKrstić, V., Filipović, I., & Ristić Trajković, J. (2024). Cultural Sensitivity and Social Well-Being in Embassy Architecture: Educational Approaches and Design Strategies. Sustainability, 16(20), 8880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208880