Systematic Review (2003–2023): Exploring Technology-Supported Cross-Cultural Learning through Review Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the trends and patterns in the selection and usage of keywords, databases, and selection criteria in research on technology-supported cross-cultural learning?

- (2)

- How do different theoretical foundations inform the conceptual frameworks and approaches used in studying technology-supported cross-cultural learning?

- (3)

- What insights and implications can be derived from content analysis of research articles on technology-supported cross-cultural learning, and how do they contribute to our understanding of the field?

- (4)

- What are the prevalent research questions that have been explored in the field of technology-supported cross-cultural learning?

- (5)

- What findings have emerged from existing studies on technology-supported cross-cultural learning?

- (6)

- What are the limitations and gaps in the existing studies on technology-supported cross-cultural learning, and how do they inform future research directions in this field?

2. Methodology

2.1. Scope of the Review of Review Studies

2.2. Strategic Search of the Review of Review Studies

2.3. Timeliness of the Literature

2.4. Included Review Studies

2.5. Choosing and Applying Review Quality Tools

2.6. Synthesis and Reporting

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Keywords, Databases, and Selection Criteria

3.1.1. Keywords, Number of Papers, and Timeframe

3.1.2. Databases

3.1.3. Selection Criteria

3.2. Theoretical Foundation

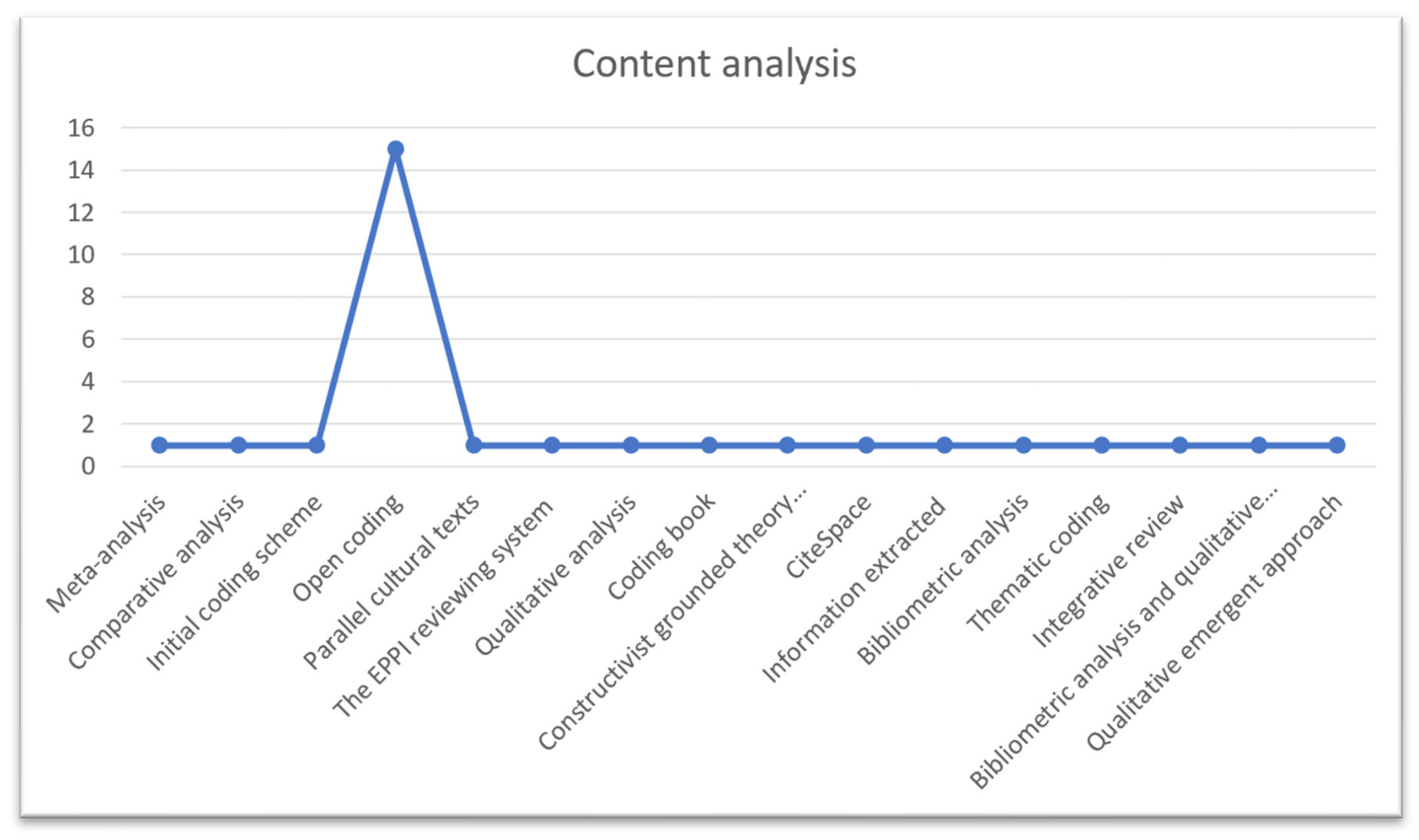

3.3. Content Analysis

3.4. Research Questions

3.5. Findings

3.6. Limitations Reported in Reviewed Studies

4. Conclusions, Recommendation, and Limitations

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Our Recommendations

4.3. Limitations of the Present Study and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s) | Keywords | No. of Keywords | No. of Papers | Timeframe | Duration (in Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akiyama and Cunningham (2018) [35] | Linguistics and language behavior abstracts; MLA international bibliography; communication mass media complete; and Google Scholar | 4 | 55 | 1996 to 2016 | 20 |

| 2 | Avgousti (2018) [43] | Telecollaboration or telecollaborative; intercultural communication; intercultural competence; intercultural communicative competence or (online) intercultural exchange | 6 | 57 | 2004 to 2015 | 11 |

| 3 | Barbosa and Ferreira-Lopes (2021) [14] | Telecollaboration or collaborative online international learning or virtual exchange or online intercultural exchange or global virtual teams or intercultural virtual collaboration or globally networked learning or e-tandem or teletandem | 9 | 57 | 2008 to 2020 | 12 |

| 4 | Barrot (2021) [54] | ABS (facebook OR instagram OR kuaishou OR linkedin OR myspace OR pinterest OR qq OR reedit OR skype OR snapchat OR tiktok OR tumblr OR twitter OR wechat OR weibo OR whatsapp OR youtube) AND PUBYEAR > 1998 AND PUBYEAR < 2020 AND SRCID (21100870382 OR … 21100913591) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; ar) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; re) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; no) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; cp) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; sh) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; ch) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; dp) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE; Undefined)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE; English)) | 44 | 96 | 2008 to 2019 | 12 |

| 5 | Çiftçi and Savas (2018) [8] | Telecollaboration | 1 | 17 | 2010 to 2015 | 15 |

| 6 | Çiftçi (2016) [31] | Intercultural learning; cross-cultural learning; intercultural competence; intercultural understanding; intercultural exchange | 5 | 26 | 2004 to 2014 | 10 |

| 7 | Gallagher and Savage (2013) [36] | Online community; virtual community; social networking; cross-cultural; culture; multicultural | 6 | 36 | 2000 to 2011 | 11 |

| 8 | Hein et al. (2021) [56] | Foreign language; mixed reality; learning; virtual reality; teaching; augmented reality; perspective; immers; learning; teaching; perspective; education; virtual exchange; intercult; attitude; change | 16 | 54 | 2001 to 2020 | 20 |

| 9 | Istifci and Ucar (2021) [37] | Unspecified | NA | 23 | 2016 to 2020 | 5 |

| 10 | Ivenz and Klimova (2022) [10] | Intercultural communicative competence and intercultural communication; activities/activity and development | 5 | 8 | 2019 to 2022 | 3 |

| 11 | Jiang et al. (2021) [11] | Cultural competence; multiculturalism; multicultural education; professional development; international education; intercultural competence; intercultural competency; intercultural learning; intercultural teaching; international relations; innovation and technology | 11 | 5 | 2007 to 2018 | 11 |

| 12 | Kolm et al. (2022) [33] | Competence; online education or distance education; international educational; and international collaborations | 5 | 14 | 2001 to 2017 | 17 |

| 13 | Lewis and O’Dowd (2016) [34] | Telecollaboration and online intercultural exchange; e-tandem and virtual exchange | 4 | 76 | 1990 to 2015 | 25 |

| 14 | Manca and Ranierit (2016) [38] | 1 | 147 | 2012 to 2015 | 4 | |

| 15 | O’Dowd (2016) [55] | Telecollaboration; online intercultural exchange; virtual exchange; collaborative online international learning (COIL); internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education; and e-tandem or teletandem; etwinning and epals | 9 | 96 | 2016 | 1 |

| 16 | Parmaxi and Zaphiris (2016) [53] | CALICO; ReCALL; Language Learning and Technology; CALL | 4 | 163 | 2009 to 2010 | 1 |

| 17 | Parmaxi (2020) [6] | Virtual reality-related keywords: (virtual environment or immersive environment or virtual reality learning environment or virtual reality environment or virtual world VR or VRLE or virtual classroom or virtual class); language learning-related keywords: (language learning or computer-assisted language learning or technology-enhanced language learning or language learning or language courses or language classroom | 15 | 26 | 2015 to 2018 | 4 |

| 18 | Peng et al. (2020) [44] | Intercultural competence; intercultural communication competence; intercultural communicative competence | 3 | 663 | 2000 to 2018 | 18 |

| 19 | Piri and Riyahi (2018) [30] | Cross-culture/al; interculture/al | 2 | 25 | 2007 to 2017 | 10 |

| 20 | Shadiev and Dang (2022) [18] | Intercultural; cross-cultural; technology; virtual; collaborative; global; competence; skill; exchange; sensitivity; understanding; knowledge; online; learning in different combinations; e.g., intercultural online | 15 | 28 | 2010 to 2021 | 11 |

| 21 | Shadiev and Liu (2022) [63] | Speech; voice; recognition; learning; instruction; and education | 6 | 26 | 2014 to 2020 | 7 |

| 22 | Shadiev and Sintawati (2020) [50] | Cross-cultural; intercultural; learning; teaching; instruction; education; knowledge; understanding; attitude; competence; awareness; skills; technology in different combinations | 13 | 25 | 2014 to 2019 | 5 |

| 23 | Shadiev and Wang (2022) [61] | 21st century skills; language learning; technology; creativity and innovation; critical thinking; problem solving; communication; collaboration; digital literacy; information literacy; media literacy; ICT literacy; flexibility and adaptability initiative and self-direction social and cross-cultural interaction; productivity and accountability; leadership and responsibility | 17 | 34 | 2011 to 2022 | 10 |

| 24 | Shadiev and Yu (2022) [64] | Foreign; second; language; cross-cultural; intercultural; multicultural; trans culture; cross-culture; interculture; multiculture; culture; telecollaboration; learning; instruction; technology and computer. | 16 | 53 | 2015 to 2020 | 5 |

| 25 | Shadiev et al. (2021a) [40] | Technology; cross-cultural; intercultural; cultural; culture; teaching; learning; understanding | 8 | 23 | 2014 to 2019 | 5 |

| 26 | Shadiev et al. (2021b) [62] | 360-degree video or 360° video; and education or training or learning or teaching or instruction | 7 | 52 | 2015 to 2020 | 5 |

| 27 | Solmaz (2018) [39] | Social networking sites and language learning; social networking sites and language teaching; social network sites and language learning; social network sites and language teaching | 8 | - | 2011 to 2017 | 7 |

| 28 | Wu (2021) [22] | Telecollaboration; virtual exchange; language teacher education; intercultural learning or intercultural communicative competence; telecollaborative competence; technology-based learning; and technology integration | 8 | 36 | 2009 to 2019 | 10 |

| 29 | Yi et al. (2023) [60] | Cross-cultural, learning, intercultural, culture, teaching, exchange, competence, technology, virtual reality, mobile devices, translation techniques, online, email, Skype, computer, and web 2.0 | 16 | 37 | 2012-2021 | 10 |

| 30 | Zak (2021) [23] | VE learning outcomes: VE models (global learning experience; COIL; xculture; virtual teams; e-tandem; telecollaboration; online intercultural exchange; Soliya; international educational exchange); VE programmatic insights; telecollaboration + learning outcomes | 10 | 27 | 2009 to 2019 | 10 |

| 31 | Zhao (2003) [45] | Computer assisted language learning; second language | 2 | 9 | 1997 to 2001 | 5 |

Appendix B

| Author(s) | Databases | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Theory | Content Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akiyama and Cunningham (2018) [35] | LLBA; MLA International Bibliography; Communication Mass Media Complete; and Google Scholar | The publication date was set between January 1996 and March 2016; peer-reviewed journal articles or book chapters; only studies in English were included; studies reported both project details and substantial research findings on SCMC; studies took place between at least two geographically distant institutional groups; studies were included if the purpose of the exchange was language learning for at least one of the participating groups; the current review targeted university learners; included projects that involved at least two distinct SCMC sessions; studies were included if they used SCMC tool(s) as one of the main tools of communication. | Excluding duplicate study report; studies that solely used ACMC were excluded; review papers and position papers were excluded. | Telecollaboration | Coding book |

| 2 | Avgousti (2018) [43] | ERIC; LLBA; PsycINFO; MLA; Linguistics Abstracts; and Scopus | The article should report data from 2004 onwards; be written in English; be conducted as part of a wider formal educational context; be learners of an L2 or a FL or attending intercultural communication classes; be published as an article in a journal or a book chapter; be assessed for their ICC skills but not necessarily exclusively; be empirical in nature; telecollaborative partnership should entail some form of Web 2.0 tool and application; one of the two participating teams should be interacting. | There is no use of Web 2.0 tools and applications; participants are not students in formal educational settings; there is interaction between teachers and students rather than peer-to-peer interaction; the study is published from 2004 onwards; study is not an article or a book chapter but part of conference proceedings, a dissertation or unpublished study, bibliography of books and articles, a commentary, a review, newsletter, editorial, an interview, book introductions, or any other type; students use several online tools to develop their ICC skills but there is no interaction with other students; students interact with other students through Web 2.0 tools in order to enhance their ICC skills; intercultural tasks are means of promoting cognitive or affective factors, but ICC is not assessed; no empirical intervention; the study is a synthesis, a meta-analysis, or a systematic review. | ICC | Open coding |

| 3 | Barbosa and Ferreira-Lopes (2021) [14] | Web of Science; Scopus | Review the evolution of the telecollaboration and virtual exchange research field over the past12 years (2008–2020); retrieving studies from the Web of Science and Scopus. | Unspecified | Telecollaboration | Bibliometric analysis |

| 4 | Barrot (2021) [54] | Scopus | Scopus-indexed; language and linguistics journal; education and education-related computer science journal; published between 2008 and 2019; articles, reviews, notes, conference papers, short surveys, book chapters, books, and data papers, written in English. | Excluding some key studies from non-Scopus-indexed journals and contextualized in non-English-speaking regions; journals that are inactive (i.e., discontinued from Scopus coverage) were excluded; non-English language was also excluded. | Scientific mapping | Bibliometric analysis and qualitative analysis |

| 5 | Çiftçi and Savas (2018) [8] | Web of Science | The period was set as 2010 and 2015; the review process solely focuses on language and intercultural learning; only empirical studies. | Study excluded studies on tandem language learning; studies concentrated on developing multiliteracy skills were also not included in the review; a theoretical paper on the motivational dynamics of one individual was also rejected. | Telecollaboration | Constructivist grounded theory (GT) coding |

| 6 | Çiftçi (2016) [31] | ERIC; Education Research Complete | Empirical study with both publication in peer-reviewed journal and publication between 2004 to 2014. | Unspecified | Byram’s model | Open coding |

| 7 | Gallagher and Savage (2013) [36] | Web of Science; Science Direct; Scopus; Google Scholar; SpringerLink and ACM digital library | The research is investigating some aspect of online communities, be it using online community data or investigating opinions of some aspect of online communities; the research is investigating data or opinion from two or more differing cultures; the cultures must be compared over some research topic or hypothesis. | Unspecified | Cross-cultural analysis | Comparative cross-cultural analysis |

| 8 | Hein et al. (2021) [56] | IEEE Xplore; EBSCOhost; Web of Science; ACM digital library | Only peer-reviewed academic journals, conference papers, reports; and reviews that have been published since April 2001 to May 2020; articles written in English or German; empirical studies; article must address the learning of a second language; not explicitly search for intercultural learning; studies’ intervention had to include an immersive setting, e.g., AR, MR, VR, or a system described as immersive. | Excluding papers that had unfitting terms or did not fit the journal topic or population; excluding studies without qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods data collection; given the frequent overlap of these excluded target groups with unrelated terms related to “medical” these excluded studies were included in this category; excluding an exchange program and not about immersion through a technical medium; studies were excluded for having no intervention described as immersive or without a focus on second/foreign; another seven papers were excluded due to lack of soundness of the findings and inconsistencies in the results. | Behavior change (BehaveFIT framework) | Open coding |

| 9 | Istifci and Ucar (2021) [37] | CALL journal | CALL journal was chosen; the last five volumes of CALL (i.e., Volumes 29; 30; 31; 32; 33) spanning over a period of 2016–2020 for articles investigating the use of social media by language learners and teachers as a tool for second or foreign language instruction. | Articles were read and the articles focusing on some other issues of language use on social media, the articles on the use of social media and applications designed only for language learning and review articles were excluded. | Integration theory | Open coding |

| 10 | Ivenz and Klimova (2022) [10] | Scopus; Web of Science | The search focused on the experimental and peer-reviewed journal; articles written in English; articles that belonged to the open-access category; the implementation and evaluation of the ICC activities and methods. | Case studies, surveys, theoretical studies, reviews, conference proceedings, abstract papers, posters, presentations, scientific event programs, literature reviews, book reviews, editorials, and grey literature were excluded; articles that were not written in the English language and non-open access articles were excluded as well. | ICC | Open coding |

| 11 | Jiang et al. (2021) [11] | Electronic databases; Google Scholar | Studies pertained to projects with an online element; projects were aimed at fostering teacher’s ICC. | Unspecified | ICC | Open coding |

| 12 | Kolm et al. (2022) [33] | ERIC; Web of Science; PubMed | Written in English or German; reporting original research with a focus on learners in higher education. | Excluding studies that did not describe competencies, instructional designs, and/or evaluation methods for IOC; excluding non-original research; excluding studies without a focus on learners in higher education; excluding languages not German or English; excluding no key questions answered. | International online collaboration (IOC) | Open coding |

| 13 | Lewis and O’Dowd (2016) [34] | ERIC; LLBA | Report on telecollaborative exchange; be based on empirical research; report students’ learning outcomes related to the areas of autonomy; linguistic development; intercultural competence and digital literacies; be peer reviewed. | Discarding various high-quality publications on other forms of telecollaboration; excluding overview and thematic articles; excluding non-empirical findings. | Telecollaboration | The EPPI reviewing system (EPPI-Centre March; 2007) |

| 14 | Manca and Ranierit (2016) [38] | ERIC; ERC; Web of Science; Scopus | Studies that specifically investigated Facebook as a technology-enhanced learning environment; studies that reported empirical findings; articles published in peer-reviewed English language academic journals; only empirical research. | Excluding conference proceedings, unpublished manuscripts, research abstracts, and dissertation and position papers; studies that were more conceptual in nature or those with little evidentiary support were also ignored. | Grounded Theory approach | Qualitative content analysis |

| 15 | O’Dowd (2016) [55] | The Telecollaboration in Higher Education conference which took place in Trinity College Dublin; Ireland from 21 to 23 April 2016 | Studies in telecollaboration in higher education conference in Dublin; the presentations reported using English or Spanish as a lingua franca for exchanges. | Unspecified | Bilingual–bicultural models | Parallel cultural texts |

| 16 | Parmaxi and Zaphiris (2016) [53] | CALL corpus (CALICO; ReCALL; Language Learning and Technology; CALL) | Development of the 2009–2010 CALL corpus; literature overview and initial coding scheme development; refinement of the initial coding scheme with the help of a focus group and construction of the CALL map version 1.0; refinement of the CALL map version 1.0 following a systematic approach of content analysis and development of the CALL map version 2.0; evaluation of the proposed structure and inclusiveness of all categories in the CALL map version 2.0 using a card-sorting technique; development of the CALL map version 3.0. | Unspecified | Culture-centered design (CCD) | Initial coding scheme |

| 17 | Parmaxi (2020) [6] | VR corpus journal | Include empirical study; date from January 2015 to September 2018; belong to an academic venue and include an abstract. | Excluding articles reporting on non-empirical studies, literature reviews, editorials, or book/product reviews; excluding articles that were incorrectly selected in the search process (false positives). | Investigating unexamined questions | Information extracted (IE) |

| 18 | Peng et al. (2020) [44] | Web of Science | Database was selected as the Web of Science Core Collection—SSCI from 2000 to 2018; the document type was refined into article and language was refined into English; author, title, source, abstract, citation, and other information were extracted and saved into plain text. | Unspecified | ICC | CiteSpace |

| 19 | Piri and Riyahi (2018) [30] | CALL (CALICO; ReCALL; LLT; and CALL) | Empirical research; studies between 2007–2017. | Unspecified | ICC | Qualitative emergent approach |

| 20 | Shadiev and Dang (2022) [18] | Web of Science | Published during 2010–2021; published in English; belong to education and educational research; focused on use of technology to promote intercultural learning in different learning contexts. | Excluding publications not published during 2010–2021; excluding publications not published in English; excluding publications not belonging to education and educational research; excluding publications not focused on the use of technology to promote intercultural learning in different learning contexts. | Various learning contexts | Open coding |

| 21 | Shadiev and Liu (2022) [63] | Web of Science | Articles published from 2014 to 2020; published in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) journals; reporting research on applications of SRT to assist language learning; articles published as full texts and in English. | Unspecified | The hidden Markov modeling (HMM) approach | Open coding |

| 22 | Shadiev and Sintawati (2020) [50] | Web of Science | Published during 2014–2019; (2) focused on intercultural learning supported by technology; published in English; indexed by the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). | Unspecified | Byram’s model | Open coding |

| 23 | Shadiev and Wang (2022) [61] | Web of Science; peer-reviewed instructional materials online | Published during 2011–2022; published in English; focused on technology-supported language learning and 21st century skills. | Excluded articles from the study that did not focus on technology-supported language learning and 21st century skills; conference papers, books, and dissertations were excluded. | Second language acquisition theory; sociocultural theory; and constructivism theory. | Open coding |

| 24 | Shadiev and Yu (2022) [64] | Web of Science | Studies published SSCI journals; published between 2015 and 2020; studies on CALL with a focus on intercultural education; studies published in English; empirical studies. | Unspecified | Sociocultural theory | Open coding |

| 25 | Shadiev et al. (2021a) [40] | Web of Science; ERIC; and Scopus | Published between 2014 and 2020; published in English; published as full texts; published in the social science citation index (SSCI); not a review study; focused on technology-supported cross-cultural learning. | Unspecified | Cross-cultural communication | Open coding |

| 26 | Shadiev et al. (2021b) [62] | Web of Science; Superstar Discovery; Baidu Scholar | Articles were published in journals; non-duplicate articles and articles in English; published as full texts; articles that focus on 360-degree video and its applications to education; articles that correspond to peer-reviewed publications were excluded. | Excluding articles were not published in journals; excluding duplicate articles; excluding those not in English; excluding not published as full texts; excluding articles that did not focus on 360-degree video and its applications to education; excluding articles that do not correspond to peer-reviewed publications. | Situated learning theory | Open coding |

| 27 | Solmaz (2018) [39] | ERIC; JSTOR; Web of Science; DOAJ; Science Direct; Google Scholar | The focus of the research had to be on the use of global or local mainstream social networking sites (SNSS) in the context of L2 teaching and learning; research had to be published in indexed and peer-reviewed international journals between 2011 and 2017. | Excluding studies featuring educational SNSS; excluding the SNSS which used other web resources (e.g., blogs, e-mails) as data sources; excluding book reviews and conference proceedings; excluding theoretical papers and attitudinal studies. | Social networking sites | Comprehensive descriptive approach |

| 28 | Wu (2021) [22] | EBSCO; Academic Search Complete; Education Research Complete; ERIC; Professional Development Collection; Teacher Reference Centre | Report on telecollaboration projects involving teachers across geographical locations; based on empirical research; published in English; published in peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, or book chapters; conducted between 2009–2019; focused on teacher learning in telecollaboration | Studies were excluded if they involved language learners as the only participants (other than teachers as learners) or focused on the use of telecollaboration for student-level learning purposes (e.g., language learning). | Telecollaboration | Thematic coding |

| 29 | Yi et al. (2023) [60] | Social Science Citation Index | Articles published in English; articles published between 2012 and 2021; articles published in SSCI journals; articles related to technology-enhanced intercultural learning. | Studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. | ICC | Open coding |

| 30 | Zak (2021) [23] | ERIC; ProQuest; Google Scholar; the library at a U.S. Higher Education Institution | Only English language articles published in U.S. peer-reviewed journals, practitioner-based resources; book chapters; books and articles published between 2009 and 2019; conducted on VE programs; articles pertaining to both undergraduate and graduate students’ experience; articles about practitioner experience, program design/models, and curriculum of the VE program. | Studies were excluded if they did not focus on higher education to stay consistent with the parameters of the study. | Integration theory | An integrative review coding |

| 31 | Zhao (2003) [45] | ERIC | An empirical study or multiple studies; technology was more broadly conceived than just computers; the studies included for the final meta-analysis. | Unspecified | Issues of effectiveness | Meta-analysis |

Appendix C

| Author(s) | Research Question(s) | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akiyama and Cunningham (2018) [35] | What are the typical arrangements of SCMC-based telecollaboration (e.g., participants, project set-ups, and interaction set-ups)? How have SCMC-based telecollaboration projects changed over the last two decades? | Participant characteristics: The most frequently reported configurations involved 2 groups of FL learners and 113 cultural groups from 25 unique countries. The USA participated most often, followed by Germany and Spain; about one-third of the cultural groups spoke English as their L1; projects featuring participants who speak languages other than major European languages started to appear after 2010; only 1 less commonly taught language (LCTL) (i.e., languages other than English, Spanish, German, and French) was featured in the top 5; of the 55 study reports, 30 reported participants’ FL proficiency level using proficiency bands based on established frameworks, such as Common European Framework of Reference, 7 studies reported the course levels, and 11 studies reported both proficiency and course levels. There were two studies without any reference or courses. Project set-ups: Most of the projects were either monolingual or bilingual in contrast to the paucity of multilingual and lingua franca projects; it was found that the average duration of a project was about 10.54 weeks with an SD of 4.19 weeks. The longest project lasted for 26 weeks, and the project with the shortest duration lasted for 4 weeks; many projects were text-based (k = 23) or combined text chat with video interaction (k = 12). There were also projects that did not use any written modality: video chat only (k = 12), audio chat (k = 2), audio-graphic (k = 2), and both audio and video chat (k = 1); concurrent use of ACMC tools: 62% of ACMC was via email, 16% was via blogs, 14% was via wikis or websites, and 11% was via discussion forums. Only one study used the social networking site Facebook alongside SCMC. Interaction set-ups: We identified five types of interaction formation when participants engage in SCMC: (1) 1 vs. 1 (i.e., dyads), (2) 1–2 vs. 1, (3) small group, (4) mid-size group, and (5) class vs. class; many of the projects used information exchange tasks, and language-focused tasks were the least common, while many projects (k = 23) designated when to use which language for how long (e.g., tandem model). Ten studies adopted the bilingual mode, allowing participants to use a language of their choice. |

| 2 | Avgousti (2018) [43] | What empirical research has been undertaken on the impact of Web 2.0 tools and applications on the intercultural communicative competence of learners of a second or foreign language? How do online intercultural exchanges with Web 2.0 tools and applications affect the development of intercultural communicative competence of learners of a second or foreign language? | The intercultural competences which might have been developed throughout the exchanges, and the role that the tools and their modalities might have had in the development of L2 or FL learners’ ICC; some researchers found that the use of critical reflections, explicit comparisons, and questions served as indicators of learning; tools and multimodality, however, affected their ICC skills to a greater extent; the study tends to use the words countries and cultures interchangeably and ignores the multiplicity of several cultures within a nation; challenges encountered included equal participation in tasks, negative attitudes, cultures-of-use’ of the tools used, lack of challenging others’ views, lack of critical reflection and higher-order thinking, absence of and intercultural awareness or competence. |

| 3 | Barbosa and Ferreira-Lopes (2021) [14] | Unspecified | 254 articles were retrieved; many of the studies were published by affiliated authors from USA universities, while other countries with relevant number are Spain, Brazil, China, and the United Kingdom; journal co-citation shows that the top leading journals in terms of co-citations are the USA, Spain, China, the Netherlands, and the UK, etc. In terms of citations, the most prominent authors are Robert O’Dowd from Universidad de León, in Spain; the research streams that comprise a larger number of studies are language development, intercultural communication, and teacher education; the most frequents word is telecollaboration; the analysis of keywords highlighted the use of two main terms: intercultural competence and learner autonomy; the most used technological sources are blogs, Facebook, social media, digital storytelling, wikis, and Skype. |

| 4 | Barrot (2021) [54] | What are the characteristics of the scientific literature in terms of context, research design, target language, social media use, and orientation of results? What is the research productivity and growth trajectory of scientific literature on social media as a language learning environment in the past 12 years? How is the scientific literature distributed in terms of geographical location and publication venues? How did the topical foci develop over the past decade? | The characteristics of the selected studies in terms of the target language, context, research design, and social media use; research productivity and trajectory; the research productivity in this field between 2008 and 2019 totals 396 documents from 160 source titles; geographically, nearly half of all documents were published by Asian-affiliated scholars. For North America, Europe, Australia, and Oceania, etc., the topical foci have expanded to all social media platforms, but the most consistently explored are Facebook, Skype, YouTube, and Twitter. |

| 5 | Çiftçi and Savas (2018) [8] | What are the focal research points of telecollaborative projects in terms of language and intercultural learning? What type of participants and contexts are involved in telecollaborative projects? What types of technologies are used in telecollaborative projects? What are the major observable patterns and emerging issues in terms of language and intercultural learning through telecollaboration? | Videoconferencing, email exchanges, learning management systems, and blogs were the most frequently used tools among the studies. In at least two different country contexts, language and intercultural learning were the focal point; the synthesis revealed a prevalence of positive telecollaborative experiences; telecollaboration yielded a strong positive impact on the language learning processes and enabled people to develop their ICC on different levels; telecollaborative projects overall succeeded in fostering existing intercultural and language skills |

| 6 | Çiftçi (2016) [31] | What kinds of technologies were used in intercultural studies? What type of participants and contexts were involved? How long did the studies take place over? What were the major findings in terms of intercultural learning? How effective were digital technologies to promote intercultural learning? Are there any potential gaps and suggestions for further research directions? | Online discussion boards were the most frequently used ones in the studies, and studies were conducted with participants from at least two different countries or cultures; analyses revealed that most of the participants completed intercultural projects with satisfactory feelings; myriad intercultural opportunities were provided by the studies in terms of learning target culture; intercultural communication through technology triggered learners to develop interculturally; computer-based digital tools enabled people to communicate with people from other cultures without visiting each other; most of the studies in the literature were designed around language learning or teaching; training before the intercultural experience also needs to be designed and implemented carefully; most of the studies took around one semester to be completed. |

| 7 | Gallagher and Savage (2013) [36] | Unspecified | Comparative cross-cultural analysis focus on comparative cultures and comparative communities; there were five common research methodologies used, namely surveying, content analysis, mixed methods, qualitative interviewing, and ethnography. Sampling methods included convenience, maximum variation, snowball, probability, judgment, and random sampling; intra-comparative studies compared different cultures within a single online community |

| 8 | Hein et al. (2021) [56] | How are virtual, fully immersive learning environments used for foreign language learning? Which characteristics of immersive technology support foreign language learning? Can virtual, fully immersive learning environments increase motivation and success in learning a foreign language? Can they change participants’ attitudes through intercultural encounters? How are they used for teacher training? | Investigation forms included blended learning (BL), experiment (between-design), experiment (within-design), and solely qualitative studies, such as semi-structured interviews; the studies used the AR medium (50%). The next largest share is taken by studies with MUVE’s (24%), 13% of the studies showed the 360 contents via an HMD or using Smart Spaces, only 13% of the studies used fully immersive VR applications, and still, none of these studies defined immersion according to the designated definition; most studies compared the findings over time (31%), particularly in blended learning studies or studies with at least two measurement points: learning achievements (examined in 31 studies) and qualitative and subjectively observed measures (examined in 35 studies) accounted for the largest proportions; teachers often found the systems used very motivating and enjoyable. |

| 9 | Istifci and Ucar (2021) [37] | Unspecified | Studies investigating social networking mostly found Facebook, Facebook and Twitter, Twitter, WeChat, and Papa; videoconferencing tools, like Skype or Zoom, can be utilized in language teaching and learning for various purposes; wikis have attracted the attention of researchers, teachers, and learners who would like to find new ways to enhance L2 development; for blogging, researchers have investigated the topic in relation to language teaching and learning, focusing on its potential contributions to the writing and speaking skills of learners; the forum NaverCafe can be used in the vocabulary teaching part of an EFL reading class at a South Korean university. |

| 10 | Ivenz and Klimova (2022) [10] | What kind of activities can enhance the development of intercultural communicative competence? Which of the presented activities are stimulating for students of foreign languages, and why? | Two research studies focus solely only on one activity aimed at the development of the ICC of the students (telecollaboration, scavenger hunt); the number of participants in the samples ranges from twenty students to forty-two students in one study; students who participated in these studies were university students; the classes were either classes for English for specific purposes (ESP) or general English (GE) classes; the outcome knowledge was checked by the researchers by observing the lessons, using questionnaires, surveys, interviews, and teacher notes and journals. |

| 11 | Jiang et al. (2021) [11] | They pertained to projects with an online element; they said projects were aimed at fostering teacher’s ICC. | Teachers are encouraged to construct active collaborative learning, share knowledge and experience, negotiate contradictory views, apply and transfer knowledge, think critically, and solve problems in a shared virtual CoP; compared with traditional modes of face-to-face intercultural training, like workshops, seminars, or conferences, online training has more advantages in terms of flexibility pace, location boundaries, affordability, and anonymity. |

| 12 | Kolm et al. (2022) [33] | What competencies do students in higher education need to develop during their studies to achieve effective IOC? Which instructional designs are used in higher education to promote the development of IOCCs? how can IOCCs and their development be evaluated? | The competence domains emerging from the literature: ICT mostly used Web 2.0 tools, and Byram’s model of intercultural communication is widely used; characteristics, such as openness and perspective-taking, etc., were found to be supportive in communication; self-management and organization, such as planning tasks thoroughly in advance and meeting deadlines, was explored; collaboration, part of collaboration competencies, including intercultural, communication, and self-management competencies, was explored; domain-specific knowledge, including job expertise and technical knowledge, was mandatory for collaboration to achieve shared goals and substantive knowledge in the form of domain-specific competencies to interact in a globally interdependent world. Instructional designs used to promote IOCCs: Telecollaboration, reviewing articles, critically analyzing examples from online exchanges, and collaboratively designing guidelines and assessment tools to organize a telecollaborative project; PBL, collaborative learning using wikis and online projects. Evaluation methods for IOCCs: Evaluating ICT competencies used self-developed questionnaires, which were self-developed and non-standardized, and which measured self-perceived competence using the computer, pre- and postsurvey, on perceived comfort and perceived knowledge for using technology tools, with a questionnaire based on proficiency in technical experimentation; for evaluating intercultural and cultural competencies, they applied content analysis to online forums, interviews, and reports, using Byram model for content analysis, a modified coding scheme for individual and social accountability, cognitive and organizational behaviors, and standardized questionnaires; they self-assessed team processes, communication modes, outcomes, and learning, but did not provide an in-depth description of the questionnaire. |

| 13 | Lewis and O’Dowd (2016) [34] | Unspecified | The most-used technologies were asynchronous; one of the primaries aims of online exchange has been second language learning; cultural misunderstanding, miscommunication, and conflict appear early in the literature; there is some evidence that working together in online environments can help learners to become more autonomous with digital literacy. |

| 14 | Manca and Ranierit (2016) [38] | Unspecified | Demographics of the studies were coded as studies on the formal use of Facebook in formal learning settings, on informal use in formal learning settings, and use in informal learning settings; Facebook was the most used, while the group, pages, or apps (N = 5) were much less frequently used and were adopted to conduct discussion and peer learning or to share resources. Facebook as a learning tool’s popularity was due to the familiarity of Facebook among students and pedagogical reasons (3). Facebook affordances: all three affordances were found to significantly increase along the continuum of formality/informality. |

| 15 | O’Dowd (2016) [55] | Unspecified | There is increasing diversity in the way telecollaboration is being integrated; telecollaborative practice have traditionally involved language learners; critical telecollaboration attempts to refocus online intercultural exchange; cross-disciplinary telecollaborative initiatives which engage students; many educators are integrating online intercultural collaboration with other forms of instruction and study programs; there has been a growing demand among practitioners to establish a framework; more than 15 presentations looked explicitly at the role of videoconferencing in telecollaborative interaction. |

| 16 | Parmaxi and Zaphiris (2016) [53] | Unspecified | Research in this group focused on the effects of SCMC on learners’ cognitive and affective development in a second language (L2); researchers in asynchronous CMC (ACMC) seek to identify and evaluate the affordances of various ACMC modes in L2 development; research in mixed CMC has a comparative aspect in the sense that it sets the affordances of SCMC vis a vis the affordances of ACMC and face-to-face interaction. |

| 17 | Parmaxi (2020) [6] | Map the use of VR technologies, the language learning settings, and the duration of educationalactivities; find potential benefits from using VR as an educational tool in the language classroom; suggest future research directions regarding the educational use of VR based on the reviewedliterature. | The VR technologies majority employed Second Life, OpenSimulator, or customized virtual environments, other studies employed a platform based on the cloud, a hybrid virtual environment, or Google Street View virtual environment for exploring cultural learning; the majority of the studies included university students, primary school students, and vocational training, secondary school students, and early childhood education; languages had English as their target language; the majority of the manuscripts employed VR for approximately 1–10 tasks or sessions; the VR corpus has demonstrated that the majority of studies benefit from using VR, boost students’ learning, and reform the learning and teaching experience; future directions can be suggested, such as real-life task design, alignment of VR features with learners’ strategies, cognitive processes and practices, cross-discipline research, large-scale studies, intercultural enhancement, experimental studies, twenty-first century skills, design principles for accessible and effective virtual worlds, kinesthetics VR, innovation in all levels of education, affordable VR, and fully immersive virtual experiences. |

| 18 | Peng et al. (2020) [44] | (1) What is the temporal distribution of published papers on ICC research? What are the major publication countries (regions) and institutions in the field of ICC research? What are the highly cited journals in the field of ICC research? Who are the highly cited authors in the field of ICC research? What are the highly cited references in the field of ICC research? What are the research hotspots in the field of ICC research? | The number of published articles shows an ostensible upward trend in terms of temporal distribution since 2007; the first five highly cited countries are the USA, China, Australia, Spain, and the UK; The International Journal of Intercultural Relations (IJIR) is found to be the most highly cited journal within the past twenty years; the first five most highly cited authors are Michael Byram, Darla Deardorff, Claire Kramsch, Mitchell Hammer, and Milton Bennett; “Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence” is the most highly cited article; blog entries, medical student, academic expatriate, and global management competencies are found to be the top four ICC research hotspots. |

| 19 | Piri and Riyahi (2018) [30] | Unspecified | Positive attitudes toward using digital tools in intercultural language learning; the development of critical cultural awareness and intercultural communicative competence; opportunities for improving all aspects of language learning; textbooks are still the predominant learning resource; a necessity felt for special technical skills and competencies. |

| 20 | Shadiev and Dang (2022) [18] | What is the research focus in reviewed studies? On what theoretical foundation reviewed studies were built? What technologies were used in reviewed studies? What were the learning contexts in reviewed studies and what was their connection to intercultural learning? What were the countries, languages, and participants in reviewed studies? What learning activities were designed in reviewed studies? What data were collected by researchers in reviewed studies? What findings were reported in reviewed studies? | Most studies focused on intercultural competence which includes multiple subdimensions; the most frequently used theories were Deardorf’s Process Model of ICC and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory; Skype was the most frequently used technology; teacher education was the most studied field; China and the USA were the countries most involved in cross-cultural activities, all studies used English for communication, the academic level of most participants was undergraduate level, the number of participants in most activities was less than 50; cooperation, synchronous communication, and production were the most used activity; all studies used qualitative research methods; meanwhile, there were twelve studies that used mixed research methods; intercultural activities were proved to promote students’ intercultural competence, though not all subdimensions improved. |

| 21 | Shadiev and Liu (2022) [63] | What were the domains and skills in the reviewed articles? What technology did scholars use and what were their applications? Who were the research participants and what was the duration of the interventions in the reviewed articles? What measures did scholars use in the reviewed articles? What results were reported of the reviewed articles? What were the reported advantages and disadvantages of the reviewed studies? | The domain included language learning, cross-cultural learning, and distance learning; scholars used Dragon Naturally Speaking, Google Speech Recognition, Windows Speech Recognition, an automatic speech recognition (ASR)-based CALL system, partial and synchronized captioning (PSC), and Julius; participants were from college, elementary school, junior high school, and preschool. Durations: less than one hour, less than one day, less than one week, less than one month, more than one month, or not specified at all; measures are a questionnaire, pre-/posttest, interviews, content of reflective notes, created texts, and think-aloud protocols, learning logs, EEG recordings, fieldwork methods, eye tracking, task analysis, language learning logs, and usability reviews; the results can be divided into five areas: (1) gains in proficiency—there were changes in certain language skills after the intervention; (2) perceptions—students’ perceptions of the intervention; (3) questions, suggestions, or approaches—some questions were raised after the intervention and suggestions or approaches were proposed; (4) system design—results concerned the system design; (5) learning logs—records of system usage for language learning; there were advantages of using speech recognition technology, such as improving affective factors, enhancing language skills, promoting interaction, creating a self-paced learning environment, and improving autonomy, increasing learning involvement, self-monitoring errors, enhancing intercultural sensitivity, supporting learner differences, reducing task completion time, and developing awareness of intelligibility. Some disadvantages were also reported: the low accuracy rate of the system, its insufficiency (i.e., SRT lacked some useful features to support learning efficiently), the system placing a burden on some students, and it being time-consuming to use. |

| 22 | Shadiev and Sintawati (2020) [50] | What kind of technologies were used in intercultural studies? What methods, cultures, languages, and participants were involved? What kind of learning activities were designed in intercultural studies? What problems associated with intercultural learning implementation were reported in the reviewed studies? | The most frequently used technologies were videoconferencing and email; mixed research methods were prevalent in reviewed studies; the US and China were the most frequently involved countries, English was the most frequently used language, and most participants were undergraduates and secondary school students; the main learning activities were self-introduction, culture introduction, and interaction; the two most important dimensions of intercultural learning were knowledge and critical cultural awareness; there were problems related to methodology, learning process, and technology identified in the reviewed studies. |

| 23 | Shadiev and Wang (2022) [61] | What language skills and 21st century skills did the researchers focus on in the reviewed studies? What theories were used as a foundation in reviewed studies? What technologies were used to promote language skills and 21st century skills? What learning activities were used in the reviewed studies? What were the methodological characteristics of the reviewed studies? What research findings were obtained in the reviewed studies? | Reviewed studies had focused most frequently on such language skills as speaking and writing and on such 21st century skills, such as communication and collaboration; the social constructivism theory was often used; Facebook, Google Docs, and Moodle were popular technologies in reviewed studies to facilitate language and 21st century skills; the following five types of learning activities were used to support learners’ language learning and 21st century skills: (1) collaborative task-based language learning activities; (2) language learning activities based on online communication; (3) creative work-based language learning activities; (4) adaptive language learning activities based on learning platforms; (5) language learning activities based on multimedia learning materials; most of the studies had a sample size of 11–30, the most common study period was 3–6 months, the data collection method often used by researchers was questionnaires, the most common method to collect quantitative data was tests, and the most common method to collect qualitative data was interviews. |

| 24 | Shadiev and Yu (2022) [64] | What was the theoretical foundation of the reviewed studies? What technologies were used by participants in the reviewed studies? What languages and cultures were involved in the reviewed studies? What methodologies were applied by scholars to the reviewed studies? What results were reported in the reviewed studies? | Mixed research methods were prevalent in reviewed studies; the US and China were the most frequently involved countries; English was the most frequently used language; most participants were undergraduates and secondary school students. |

| 25 | Shadiev et al. (2021a) [40] | What theoretical foundation was used in the cross-cultural studies under consideration? What curricula did the cross-cultural studies use? What technologies were applied in the cross-cultural studies? What methodology was used in the cross-cultural studies? What were their main findings? | Reviewed studies built their research frameworks mostly based on Byram’s model and the cultural convergence theory; studies could be categorized in terms of the curricula focus into (a) cross-cultural learning, (b) linguistic skills, and (c) pre-service teacher training; the most frequently used technologies to support cross-cultural learning were Skype, e-mail, and blogs; most of the reviewed studies comprised a combination of both qualitative and quantitative data; most of the reviewed studies reported the role of technology in cross-cultural learning and how technologies can support FL/SL learning and pre-service teacher training; the reviewed studies pointed out several issues encountered during the cross-cultural learning process and suggested corresponding solutions. |

| 26 | Shadiev et al. (2021b) [62] | What 360-degree video tools were used in the field of education? What were the theoretical bases of the reviewed studies? What methodologies were applied to the reviewed studies? What results were reported in the reviewed studies? | The most frequently used tools (i.e., cameras) to create 360-degree videos were GoPro and Samsung, scholars also used Insta 360, LG 360 CA, Ricoh Theta V, and 360fly 4k cameras in the reviewed studies; the theories were grouped into cognitive theory, social learning theory, behavioral theory, situated learning theory, and affective learning theory; the most popular domains were medicine and healthcare, language, culture, science, and teacher education; there were twelve studies with less than thirty participants involved. Participants watched 360-degree videos; 360-degree videos were created by professionals; 360-degree videos were created by participants; 360-degree videos were obtained from other sources and 360-degree videos were obtained from unspecified sources; durations were less than 30 min, between 30 and 60 min, between 1 and 6 h (n = 9), between 1 day and 1 week (n = 2), between 1 week and 1 month, and more than 1 month; scholars used questionnaires, tests, interviews, surveys, student reflection, teacher evaluations, and peer evaluations; scholars reported about improved learning outcomes, positive attitudes toward 360-degree video, user experience, behavioral changes, and motivation. |

| 27 | Solmaz (2018) [39] | What are the emerging themes and issues addressed in the previous scholarship of SNS use in L2TL settings? What are the pedagogical considerations for SNS integration into L2TL? | The value of SNSs as a general resource to create new avenues for practicing a multitude of language areas and literacies is dominantly present in the literature; SNSs were shown to create spaces for learners to be exposed to authentic input in an informal context with opportunities for authentic output; previous studies suggest that SNSs may play a role in assisting L2 learners in developing intercultural competence and socio-pragmatic skills in socio-interactive online environments; a high level of interaction in social networking spaces naturally resulted in the exploration of online communities in the L2TL context; identity performance and self-presentation are often experienced in SNSs, mostly because such virtual worlds enable learners to experiment with multiple identities more safely as they do not occur in a monolithic real world. |

| 28 | Wu (2021) [22] | What are the commonly reported learning outcomes of telecollaboration projects that take place for the purpose of language teachers’ professional development? What are the key themes in terms of the types of new teaching competences for language teachers to develop, new roles of project instructors, teacher perceptions of telecollaborative learning, and their preparedness for transferring the new competences to language classrooms? | Scholars of the examined studies have increasingly applied telecollaboration to prepare teachers for new competences. Researchers have conceptualized telecollaboration as experiential learning when designing tasks to boost teachers’ development; a majority of scholars in the 36 studies intentionally engaged teachers in experiential learning of telecollaboration; a task design mediator takes on multiple roles, including the role of a co-designer needed to connect participating institutions and to co-design telecollaborative tasks and a curriculum in the planning stage; after participating in telecollaboration projects, teachers demonstrated a variety of changes in their attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions; many scholars of the 36 studies stressed that it is as significant to prepare teachers for such issues as to teach them how to design and implement tasks relevant to intercultural learning, technology integration, and telecollaboration integration. |

| 29 | Yi et al. (2023) [60] | What is the relationship between participants and technology? What is the relationship between participants and the reported main findings? What is the relationship between the instruments and main findings? What is the relationship between study types and the main findings? Does technology have an impact on intercultural learning? | (1) Moderate evidence showed a higher frequency of the technology usage in higher education or above; strong evidence revealed that technology was applied more frequently in studies with large samples than in those with small samples; (2) moderate evidence demonstrated that most of the main findings were obtained from studies related to higher education or above; (3) moderate evidence illustrated that the main finding was intercultural learning outcome, and it was frequently obtained using various measuring instruments; (4) there was moderate evidence that mixed research was prevalent in the reviewed studies, and most of the main findings were obtained through mixed research; (5) strong evidence showed that computer vision technologies had the most significant impacts on participants’ intercultural learning. In addition, the following five relationships were identified: participants and technology, participants and main findings, instruments and main findings, types and main findings, and impacts of technology on intercultural learning. |

| 30 | Zak (2021) [23] | What are some of the VE models discussed in the literature? What are the major learning outcomes of VE? What are the programmatic insights (trends, challenges, limitations) addressed in the literature? | VE has been most often used with the intention of language learning and developing international cultural competencies; one of the best known models of VE is COIL. The Center for COIL assists in facilitating online learning and building relationships with international partners; VE programs are noting varying learning outcomes, such as language learning, peacebuilding, and international cultural competency development. The scholarship on VE mostly consists of case studies sharing analysis of programmatic features, including planning, curricular, and pedagogical visions; several scholars offer implementation guidance, including a typology of implementation models and an evaluation process of a pedagogical intervention. |

| 31 | Zhao (2003) [45] | How and in what ways is technology are effective in improving language learning? | Overviews of the literature were published in 1998 and 1999, and contain 10 feature articles; uses and effectiveness of technologies in language education is categorized into four groups: access to materials, communication opportunities, feedback, and learner motivation; assessing the overall effectiveness uses a preliminary meta-analysis. |

Appendix D

| Author(s) | Limitation(s) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akiyama and Cunningham (2018) [35] | First, there is a lack of TC projects that go beyond one semester and that feature participants whose proficiency is higher than intermediate; we need more research on TC projects that involve LCTLs; there is a paucity of multilingual and lingua franca projects; we cannot emphasize enough how important it is for TC researchers to report as many details as possible about their TC projects; finally, it is important to remember that this synthesis does not represent the entirety of SCMC-based TC, because of the 55 projects included in the synthesis. |

| 2 | Avgousti (2018) [43] | With regard to methodological limitations, methodological triangulation is suggested; limited in including a different set of databases and journals; limited in year of publication or omitting any other inclusion and exclusion criteria to extend the scope of the study; limited in focus on a different set of keywords which might uncover a different set of empirical studies; multi focus on two aspects, such as ICC and language skill, which means that the study is not specifically concerned with ICC skills. |

| 3 | Barbosa and Ferreira-Lopes (2021) [14] | Although Europe and Asia also have significant presence, there is much space to improve co-authorship in the near future. From the intercultural perspective, telecollaborative exchanges could also be much more enriched with an increased involvement of other cultural clusters; the different methodologies to identify keyword clusters and trend topics can be used in future studies. |

| 4 | Barrot (2021) [54] | The study did not examine the generalizability of the findings of the selected studies; the analysis was delimited to papers retrieved from the Scopus database within the three subject categories; the bibliometric nature of this study restricted me from differentiating between studies on formal and informal language learning contexts. |

| 5 | Çiftçi and Savas (2018) [8] | The main limitations of this synthesis paper concern potential future meta-syntheses or meta-analyses, and the study at hand had a limited scope and time. |

| 6 | Çiftçi (2016) [31] | Small number of studies; limited criteria of selection only focused on an empirical study. |

| 7 | Gallagher and Savage (2013) [36] | Small number of studies reviewed; limited scope of themes discussed. |

| 8 | Hein et al. (2021) [56] | Small number papers reviewed that should improve in the future. |

| 9 | Istifci and Ucar (2021) [37] | The scope of this study is relatively limited. |

| 10 | Ivenz and Klimova (2022) [10] | The main limitation of this review study is that only open access articles were included. |

| 11 | Jiang et al. (2021) [11] | This article has illustrated the impetus for teachers’ ICC learning and training to occupy a prominent niche in the school agenda; while the availability and quantity of such projects is lacking, this is but one area to be considered. |

| 12 | Kolm et al. (2022) [33] | First, reported results were heterogeneous and synthesis is possible only to a limited degree; second, we limited studies to the English and German language and, therefore, might have missed relevant findings of studies in other languages. |

| 13 | Lewis and O’Dowd (2016) [34] | A small number of authors have produced evidence that telecollaborative exchanges can foster the development of learner autonomy and that immersive environments may offer particularly favorable conditions. |

| 14 | Manca and Ranierit (2016) [38] | The review was performed on several databases and within a few educational-related journals; although the latter would be an optimal integrative method to take stock of this trend of research, the available studies in each of the three domains (formal use in informal learning settings, informal use in formal learning settings, and use in informal learning settings) are too heterogeneous to justify a quantitative meta-analysis. |

| 15 | O’Dowd (2016) [55] | Lack of space has meant it was impossible to look at the many different research methods which were reported at the Dublin conference. |

| 16 | Parmaxi and Zaphiris (2016) [53] | The decision to limit the corpus to four journals meant that some manuscripts that relate to CMC in language learning and teaching were not included; the results are limited to this particular corpus; however, the results may also reflect both present and future trends in the field. |

| 17 | Parmaxi (2020) [6] | Small number of studies reviewed. |

| 18 | Peng et al. (2020) [44] | On the one hand, in the process of data collection, the keywords we chose were limited which could not cover all the other different terms, like cross-cultural competence, global competence, and cross-cultural adaptation, etc. |

| 19 | Piri and Riyahi (2018) [30] | Limited databases; limited number of studies. |

| 20 | Shadiev and Dang (2022) [18] | This study only used the searched papers in the Web of Science database; this study only includes eight fields, which is too few for all disciplines. In the future, scholars may address these issues. |

| 21 | Shadiev and Liu (2022) [63] | Unspecified |

| 22 | Shadiev and Sintawati (2020) [50] | Only twenty-five research articles were reviewed, and some important studies on intercultural learning supported by technology were omitted. |

| 23 | Shadiev and Wang (2022) [61] | Articles reviewed in this study were sourced from PRIMO and Web of Science databases, and some conference papers, books and dissertations were excluded. |

| 24 | Shadiev and Yu (2022) [64] | The search for research articles was limited to SSCI journals only; another limitation is that 18 reviewed studies included no information related to theoretical foundations. |

| 25 | Shadiev et al. (2021a) [40] | Small number of articles, where only the top nineteen SSCI journals excluded conference papers, book reviews, dissertations, etc. |

| 26 | Shadiev et al. (2021b) [62] | Specific databased and inclusion/exclusion criteria used in our study were limited; we only focused on exploring such aspects as tools, theory, methodologies, and results; performing a meta-analysis in order to statistically test the effectiveness of applications of 360-degree videos on learning outcomes is another promising research direction. |

| 27 | Solmaz (2018) [39] | |

| 28 | Wu (2021) [22] | Small number of studies reviewed; limited scope of themes discussed. |

| 29 | Yi et al. (2023) [60] | Conference papers, book reviews, etc., were excluded from this study; there were not quality assessment tools for evaluating educational research articles; the researchers did not use a meta-analysis because there were few intercultural learning studies. |

| 30 | Zak (2021) [23] | Lack of methodological diversity in the published studies—most are qualitative, and many use the case study methodology; insignificant empirical exploration of the faculty/facilitator experience in planning and executing VE programs. |

| 31 | Zhao (2003) [45] | The limited number of available studies. |

References

- Batunan, D.A.; Kweldju, S.; Wulyani, A.N.; Khotimah, K. Telecollaboration to promote intercultural communicative competence: Insights from Indonesian EFL teachers. Issues Educ. Res. 2023, 33, 451–470. [Google Scholar]

- Dooly, M. The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, S.; Janssen, J.; Beach, P.; Perreault, M.; Beelen, J.; van Tartwijk, J. The effectiveness of Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) on intercultural competence development in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.G. Engaging Karen refugee students in science learning through a cross-cultural learning community. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Implementing computer-mediated intercultural communication in English education: A critical reflection on its pedagogical challenges. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmaxi, A. Virtual reality in language learning: A systematic review and implications for research and practice. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 31, 172–184. Available online: https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jcal.12486 (accessed on 22 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Kayes, D.C. An experiential approach to cross-cultural learning: A review and integration of competencies for successful expatriate adaptation. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2004, 3, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçi, E.Y.; Savaş, P. The role of telecollaboration in language and intercultural learning: A synthesis of studies published between 2010 and 2015. ReCALL 2018, 30, 278–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talalakina, E. Fostering cross-cultural understanding through e-learning: Russian-American forum case-study. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2010, 5, 42–46. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/45342/ (accessed on 22 September 2023). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ivenz, P.; Klimova, B. A review study of activities used in the development of intercultural communication competence in foreign language classes. Int. J. Soc. Cult. Lang. 2022, 10, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Soon, S.; Li, Y. Enhancing teachers’ intercultural competence with online technology as cognitive tools: A literature review. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2021, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. Essays on Moral Development: The Psychology of Moral Development; Harper & Row: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zhussupova, R.F.; Kosherova, K.K.; Dauletova, N.M.; Dyachenko, O.V.; Tolegen, A. Implementing the cultural dimensions proposed by Gerard Hofstede for intercultural multilungial communication. Hayчный жypнaл «Becmник HAH PK» 2019, 1, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.W.; Ferreira-Lopes, L. Emerging trends in telecollaboration and virtual exchange: A bibliometric study. Educ. Rev. 2023, 75, 558–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Z.; Fathi, J.; Rahimi, M. Enhancing EFL learners’ intercultural communicative effectiveness through telecollaboration with native and non-native speakers of English. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2023, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, S.; Ji, X. Beyond borders: Exploring the impact of augmented reality on intercultural competence and L2 learning motivation in EFL learners. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1234905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, L. New takes on developing intercultural communicative competence: Using AI tools in telecollaboration task design and task completion. J. Multicult. Educ. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Dang, C. A systematic review study on integrating technology-assisted intercultural learning in various learning context. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6753–6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayakhmetova, L.; Mukharlyamova, L.; Zhussupova, R.; Beisembayeva, Z. Developing Collaborative Academic Writing Skills in English in CALL Classroom. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, M.; Zhao, Y. Using an online collaborative project between American and Chinese students to develop ESL teaching skills, cross-cultural awareness and language skills. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, G.; Pegrum, M.; Lander, B.; Tomei, J.; Sonobe, N.; deBoer, M. ‘Free rein’to learn about language, culture & technology: A multimodal digital text exchange project between school students in Australia and Japan. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2023, 18, 034. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. Unpacking themes of integrating telecollaboration in language teacher education: A systematic review of 36 studies from 2009 to 2019. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2023, 36, 1265–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, A. An integrative review of literature: Virtual exchange models, learning outcomes, and programmatic insights. J. Virtual Exch. 2021, 4, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.E.; Olkin, I. Estimating time to conduct a meta-analysis from number of citations retrieved. JAMA 1999, 282, 634–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, W.Y.; Nurtantyana, R. X-Education: Education of All Things with AI and Edge Computing—One Case Study for EFL Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.W.; Reinders, H. Technology-mediated task-based language teaching: A qualitative research synthesis. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2021, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.Y.; Nurtantyana, R.; Purba SW, D.; Hariyanti, U. Augmented Reality with Authentic GeometryGo App to Help Geometry Learning and Assessments. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2023, 16, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtarkyzy, K.; Abildinova, G.; Sayakov, O. The Use of Augmented Reality for Teaching Kazakhstani Students Physics Lessons. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembayev, T.; Nurbekova, Z.; Abildinova, G. The Applicability of Augmented Reality Technologies for Evaluating Learning Activities. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, S.; Riahi, S. Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Technology-Enhanced Language Learning: A Review of Research; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçi, E.Y. A review of research on intercultural learning through computer-based digital technologies. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 313–327. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.19.2.313 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Hwang, W.Y.; Hariyanti, U. Investigation of students’ and parents’ perceptions of authentic contextual learning at home and their mutual influence on technological and pedagogical aspects of learning under COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolm, A.; de Nooijer, J.; Vanherle, K.; Werkman, A.; Wewerka-Kreimel, D.; Rachman-Elbaum, S.; van Merriënboer, J.J. International online collaboration competencies in higher education students: A systematic review. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2022, 26, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.; O’Dowd, R. Online intercultural exchange and foreign language learning: A systematic review. In Online Intercultural Exchange; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 21–66. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/47044/1/9781138932876_chapter%202.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Akiyama, Y.; Cunningham, D.J. Synthesizing the practice of SCMC-based telecollaboration: A scoping review. CALICO J. 2018, 35, 49–76. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90016521 (accessed on 22 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.E.; Savage, T. Cross-cultural analysis in online community research: A literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istifci, I.; Dogan Ucar, A. A Review of research on the use of social media in language teaching and learning. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2021, 4, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, S.; Ranieri, M. Is Facebook still a suitable technology-enhanced learning environment? An updated critical review of the literature from 2012 to 2015. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2016, 32, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, O. A critical review of research on social networking sites in language teaching and learning. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2018, 9, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.T.; Huang, Y.M. Review of research on technology-supported cross-cultural learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.J.; Yang, L.Z.; Chen, T.L. The effectiveness of ICT-enhanced learning on raising intercultural competencies and class interaction in a hospitality course. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, M. Information and digital technology-assisted interventions to improve intercultural competence: A meta-analytical review. Comput. Educ. 2023, 194, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgousti, M.I. Intercultural communicative competence and online exchanges: A systematic review. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2018, 31, 819–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.Z.; Zhu, C.; Wu, W.P. Visualizing the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 74, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Recent developments in technology and language learning: A literature review and meta-analysis. CALICO J. 2003, 21, 7–27. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24149478 (accessed on 22 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Francke, A.L.; Smit, M.C.; de Veer, A.J.; Mistiaen, P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2008, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matricciani, L.; Paquet, C.; Galland, B.; Short, M.; Olds, T. Children’s sleep and health: A meta-review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 46, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy, E.A.; Johnson, B.T.; Keenan, C. Best practice guidelines and essential methodological steps to conduct rigorous and systematic meta-reviews. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2019, 11, 353–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, A.; Karadeniz, A.; Baneres, D.; Guerrero-Roldán, A.E.; Rodríguez, M.E. Artificial intelligence and reflections from educational landscape: A review of AI Studies in half a century. Sustainability 2021, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Sintawati, W. A review of research on intercultural learning supported by technology. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Inayat, I.; Salim, S.S.; Marczak, S.; Daneva, M.; Shamshirband, S. A systematic literature review on agile requirements engineering practices and challenges. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmaxi, A.; Zaphiris, P. Computer-mediated communication in computer-assisted language learning: Implications for culture-centered design. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2016, 15, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]