Abstract

Drawing upon a survey of teachers in England conducted by the UCL Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Education (CCCSE), this paper reports on teachers of geography’s conceptions of climate change, sustainability, climate change education, and sustainability education. We address how teachers of geography across the primary and secondary phase appear to distinguish the concept (climate change or sustainability) from the concept within education (climate change education or sustainability education) given that research to date has not engaged with both these framings together in empirical research with teachers. Across both climate change education and sustainability education, there was recognition for (i) the importance of these concepts for young people, (ii) the ways in which education can support young people to make informed choices or take action, and (iii) the importance of addressing these concepts across subject curricula. Teachers’ descriptions indicate (i) disconnections between policy rhetoric and teaching, (ii) a lack of attention to social and environmental justice, and (iii) an over-focus on individual action.

1. Introduction

Teachers’ knowledge and perspectives in relation to climate change and sustainability education are of critical importance given the climate emergency, and the youth-led movements that reflect young people’s concern for action and appeal for improved climate change education [1,2].

This paper draws on a subset of the UCL Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Education’s (CCCSE) teacher survey, which sought to engage with teachers’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability education in England [3]. We have chosen specifically to focus on teachers of geography, as they teach across one of the few curriculum areas where sustainability and climate change education have been more formally recognised within the curriculum in England [4,5,6,7,8]. Focussing on teachers of geography allows us to engage in depth with survey responses from both primary and secondary teachers teaching geography from Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) through to Key Stage 5.

Typically, research studies place a focus on climate change or sustainability, and yet these concepts are inextricably bound together within and for students’ education. The main aim of this work is to examine more closely the connections between how these two distinct concepts are described, and if there are any ways in which geography as a subject or area of teacher specialism appears to influence teachers’ descriptions. We do not compare teachers of geography with teachers of other specialisms, and so we cannot claim that teachers of geography hold unique or distinctive conceptions compared to other teachers (though this is a possibility). Nonetheless, we can offer an analysis of the connections between geography, both as an academic discipline and a school subject, and the conceptions of teachers of geography.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Policy Context

Climate change and sustainability education policy in England has varied significantly in response to government ideology, and more broadly in the last 30 years, with less apparent influence from the international policy context. Since the 1990s, devolution of the home nations of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) has meant that each jurisdiction has the authority to develop and govern their own public services; consequently, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales determine their own education policy, including national curricula. Here we focus on England, although it should be noted that in Scotland, Learning for Sustainability is an entitlement for all children and young people and is embedded into the Professional Standards for Teachers [9], and in Wales, the broader field of Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship (ESDGC) has long been recognised as a priority for the Welsh government [10].

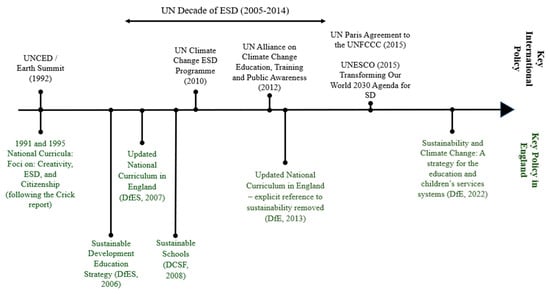

Figure 1 shows key policy in England since 1991, along with major international policy.

Figure 1.

Timeline of key international policy and policy in England [4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Whilst there is no scope in this paper to discuss the sustainability education policy landscape in depth, some points are noteworthy and relevant to the teachers’ conceptions we are exploring in this paper. There are differences between countries in how far climate change and sustainability education are embedded in national education and curriculum policy, with England lagging behind some other countries such as Scotland, Finland, and Sweden [9,20,21,22]. There is a gap between international policy, which foregrounds the sustainable development goals, and England’s government education policy, in which the goals are much less visible. Sustainability and climate change education policy in England has tended to focus on school buildings and individual behaviours, rather than encouraging an exploration of political–economic systems, social justice, and collective action [23]. In the 2007 revisions, sustainability became a prominent feature of England’s geography national curriculum, but it was removed completely in the 2013 revision under the Conservative-led coalition government [17,24]. There is an ongoing tension between the government’s sustainability and climate change education policy and other levers of curricula that pull in different directions [19,25]. These levers include the statutory Teachers’ Standards (for qualified teachers), the content of the national curriculum, the national school inspections body (Ofsted), and a focus on examination performance, encouraged by the publishing of school ‘league tables’, obliging schools to compete with one another to attract students [26]. The national policy context in England tends to have a more direct impact on schools and teachers than the international context, and is likely to influence how teachers think about climate change and sustainability in relation to teaching geography.

2.2. Teachers’ Conceptions in Relation to Climate Change and Sustainability

Researchers have engaged with teachers’ conceptions in relation to climate change, sustainability, sustainable development, and education for sustainability, as these areas of curricula have in some countries become more prominent within national curriculum documents, and there have been imperatives to embed approaches to sustainability and climate education in teacher education. Research in relation to teachers’ conceptions of sustainable development has had varying findings; for example, Summers et al. [27] identified a cohort of student teachers of geography, and science in England conveyed greater awareness around environmental than economic or social dimensions of sustainability, whereas Borg et al. [28] found Swedish teachers differed in their understanding according to subject, with science teachers emphasising environmental dimensions and social science teachers foregrounding social dimensions. More recently, English Language student teachers in Turkey were observed to associate sustainable development mostly with economic growth [29]. Studies that consider teachers in relation to climate change more frequently consider factual knowledge, most specifically around the greenhouse effect, rather than broader conceptualisation. For example, Ratinen [30] explored primary student teachers’ understanding of the greenhouse effect, finding their scientific understanding was incomplete and even misleading. Further, Bhattacharya [31] found that even secondary school science teachers’ knowledge based in relation to the science of climate change lacked depth of understanding, and teachers described being overwhelmed with the complexity of global climate change.

Within UNESCO’s Global Action Plan on Education for Sustainable Development, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is defined as allowing ‘every human being to acquire the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes that empower them to contribute to sustainable development and take informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability, and a just society for present and future generations’ [32] (p. 33). However, in relation to ESD, previous surveys have indicated that teachers have found it difficult to define and identified a need for improved professional development. For example, Sund and Gericke [33], when considering three discipline-based groups of teachers’ perspectives of their contribution to ESD, found science teachers focussed on ecological content knowledge, social science teachers (including geography teachers) regarded ESD as incorporating politically and morally oriented issues, and language teachers saw their role as bridging the sciences and social sciences through debates and discussions, thereby demonstrating that each subject area has the potential to make specific contributions to ESD [33]. Waltner et al. [34] examined what 113 teachers of sciences, social sciences, and humanities subjects in Germany think and know about ESD, identifying that while teachers’ self-reported knowledge about ESD had increased since 2007, 32.7% of teachers had still not heard of the term ESD at all. More specifically in relation to geography, Munro and Reid [35] explored student geography teachers’ perspectives on ESD in Scotland, finding they described ESD as being an important issue which should be embedded across all subjects, but that they had a lack of confidence relating to defining and delivering ESD.

However, there are limitations around this literature base. For example, much literature focusses on student teachers’ conceptions from single initial teacher programmes (e.g., science and geography student teachers from the University of Oxford [27]; craft student teachers from one university course in Finland [36]). Further, studies identify disciplinary differences between teacher (or student teacher) conceptions, and yet there lacks a more detailed understanding of geography teacher conceptions; this is critical when geography teachers are so frequently given responsibility to teach about sustainability and climate change—particularly in the English context. Of final note is that previous research almost unanimously argues the case for professional development; a detailed understanding of geography teachers’ conceptions would allow a more tailored approach to development of professional development. Accordingly, this paper reports on the national teacher survey, with a focus on teachers of geography, to explore teachers’ conceptions of climate change (education) and sustainability (education).

3. Research Design

We draw upon a survey conducted by the UCL Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Education (CCCSE), which aimed to engage with teachers’ perspectives on climate change and sustainability education in England [3]. Ethical approval for the survey was provided by UCL Research Ethics Committee. Between October and December 2022, the survey was open to teachers in England (across all subjects and phases). Teachers were reached via networks, social media accounts, and email distribution lists, including through the Institute of Education (IOE), UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society, subject associations, and the Department for Education (DfE) [3]. We narrow our focus to teachers who reported that they were currently teaching geography in either primary and/or secondary schools. Some teachers who reported teaching geography in the secondary school also stated that they taught other subjects alongside geography; these would be considered non-specialists as they were qualified to teach other subjects and did not have a degree in geography (or a related area), or a teaching qualification in secondary geography. Teachers who reported teaching geography in primary schools typically identified teaching this geography alongside the full range of school subjects taught in primary schools, and these teachers did not necessarily have any geography-related qualifications. The focus on geography allows us to place a subject that includes climate change, and where sustainability education is established within the formal curriculum, under the spotlight [4,5,6,7,8].

In our analysis, we draw upon responses by 210 teachers (104 primary teachers: teaching EYFS, Key Stage 1 and/or Key Stage 2; 99 secondary teachers: teaching Key Stage 3, Key Stage 4 and/or Key Stage 5; 7 teachers: teaching across primary and secondary phases). It is important to acknowledge that this does not provide a representative sample of teachers of geography, as it is more likely that teachers who have an interest in climate change and/or sustainability education chose to complete the survey.

In this paper, we focus on four open-ended questions from the survey. These four questions asked teachers to complete the following four sentences:

- I think of climate change as…

- I think of sustainability as…

- I understand climate change education as…

- I understand sustainability education as…

We acknowledge the importance of recognising the order in which teachers were asked about the descriptions of each concept, as this might have affected what they chose to include or leave out, or place emphasis on. For example, if teachers were only asked about climate change education, this might have incorporated more content about the concept of climate change.

We analysed the responses of teachers of geography across primary and secondary phases together. Inductive coding was carried out by one researcher for each question separately. Each teacher’s response could be coded with multiple themes (and therefore, the counts presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 add up to more than 210). The codes were then refined and subsequently reviewed by a second researcher.

Table 1.

Themes identified in relation to teachers of geography and their completion of the sentence ‘I think of climate change as…’.

Table 2.

Themes identified in relation to teachers of geography and their completion of the sentence ‘I think of sustainability as…’.

Table 3.

Themes identified in relation to teachers of geography and their completion of the sentence ‘I understand climate change education as…’.

Table 4.

Themes identified in relation to teachers of geography and their completion of the sentence ‘I understand sustainability education as…’.

4. Results

Within this section, we report on the themes identified in how teachers of geography across the primary and secondary phase describe climate change, sustainability, climate change education, and sustainability education separately. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 show the key themes identified, the number of occurrences, and two indicative responses from teachers that were coded as fitting within that theme.

Whilst some responses focussed on typical components of a dictionary or textbook definition of climate change (e.g., ‘long-term changes to temperature’), there were several themes that indicated that teachers of geography were going beyond such a definition where climate change was characterised as a ‘threat’, an area where society or individual action is required, and an issue of social justice, as shown in Table 1.

As indicated in Table 2, the United Nations’ (UN) Brundtland Commission definition was reproduced (exactly or in a similar form) by 56 teachers of geography [37]. There was also recognition for economic, environmental, and social dimensions of sustainability. Natural resource use (‘preventing further depletion of the Earth’s resources’) was often mentioned. Where teachers’ descriptions went beyond the Brundtland definition or drawing upon the three pillars of sustainability (with an environmental, social, and economic focus), teachers were often making connections to the future. There were also some responses that indicated that teachers were cynical about the ways in which sustainability has been appropriated by governments and corporations.

Within themes identified within descriptions of climate change education in Table 3, the most common responses were framed around the teaching of the ‘cause, effects and responses of climate change’; this framing is one that resonates within the framing of climate change within examination specifications [6]. Some of the other themes identified in the teachers’ responses emphasise climate change education’s importance specifically for young people, and the ways in which this education should enable students to take actions or make informed choices. There were also several responses that engaged with the need to consider the emotions that are invoked when teaching about climate change. Whilst there were several responses that acknowledged the complexity in teaching about climate change, these were in-depth responses that engaged with an understanding of the knowledge teachers wanted to engage their students with; for example, one teacher said climate change education is as follows:

a moral and ethical requirement, involving the teaching of knowledge about climatic change derived from inquiries stemming from the Scientific method, at the same time as being an opportunity to incorporate other methods, other ways of knowing and traditions of thinking human-environment relations (Indigenous knowledges etc.). (Teacher of geography)

There were also several teachers who indicated that they saw that climate change education was limited due to its limited inclusion in national curriculum and examination specifications.

As outlined in Table 4, most descriptions of sustainability education referenced the role of this in young people’s future decision making and actions. Other descriptions addressed specific knowledge about sustainability that should be included within school education. There was also a smaller number of responses that identified sustainability education as crucial, and requiring an approach where it is taught across subjects. Sustainability was also acknowledged as an underpinning concept for geography by four teachers.

5. Analysis and Discussion

In this section, we draw upon the themes identified in Section 4 to engage with the ways in which teachers of geography appear to distinguish the concept (climate change or sustainability) from the concept within education (climate change education or sustainability education) in Section 5.1 and Section 5.2, and the connections between descriptions of climate change education and sustainability education in Section 5.3.

5.1. Teachers’ Conceptions of Climate Change and Climate Change Education

Teachers of geography conceive climate change and climate change education differently. Climate change was frequently described as a ‘threat’ (Table 1). There is a despairing tone in many respondents’ conceptions of climate change, with language suggesting an emotional response (e.g., ‘a death sentence for most species on the planet’ (teacher of geography), ‘impending doom for life as we know it on planet earth’ (teacher of geography), and ‘terrifying and inescapable’ (teacher of geography)). For many of the teachers, climate change is first and foremost conceived as a tragedy. In contrast, the teachers described climate change education with rather less emotion, the predominant conception being of climate change education as teaching about the ‘causes, effects and responses of climate change’ (Table 2).

Teachers foreground geographical knowledge in their conceptions of climate change education, for example, as part of the geographical concepts that students can develop. Many teachers conceive climate change education as crucial for young people. Some teachers place emphasis on children and young people being able to take direct action, and others portray climate change education as enabling young people to make informed choices, and explicitly acknowledge that teachers should ‘not [be] telling them what they should/shouldn’t do’ (teacher of geography). In some ways this distinction could be seen to be semantic, but the former framing could be seen as placing emphasis on individual action and appears to be more directive around pro-environmental behaviours. Though, there is some ambiguity in teachers’ responses, and where teachers have not provided exemplification, it is only possible to speculate what they mean by ‘action’. However, the latter framing appears to align with some components of ‘action competence’, whereby ‘(i) knowledge of action possibilities, (ii) confidence in one’s own influence, and (iii) the willingness to act’ are considered [38], p. 742.

There is a rather more hopeful tone to teachers’ conceptions of climate change education than to their conceptions of climate change itself, and ‘hope’ is mentioned explicitly in descriptions of climate change education (e.g., ‘teaching them ways people are dealing with this socio-scientific issue-to reduce climate anxiety and increase future hope’ (teacher of geography) and ‘showing children that there are solutions, providing hope’ (teacher of geography)). The word ‘hope’ was not used in conceptions of climate change; however, some teachers might be seen to imply hope by referring to the possibility of action in their conceptions of climate change. However, the portrayal of hope in climate change tends to be in a fearful or desperate way, for example: ‘...we must act...before it is too late’ (teacher of geography). Teaching to avoid increasing young people’s fear or anxiety is mentioned in teachers’ conceptions of climate change education, which could help to explain this difference. This indicates that teachers appear to be aware of concerns around climate anxiety in children and young people [39,40,41]. However, Finnegan [42] found that hope and distress co-existed in his survey of over 512 16–18-year-old students in England. Finnegan found that the best way to foster hope was not to teach hopeful futures directly, but to allow students space to express their fears and anxiety around climate change. Therefore, this indicates the limitation of a framing of teaching with hope to try to reduce or minimise fear and anxiety.

Some teachers conceive both climate change and climate change education as complex, or in some cases super-complex and ‘wicked’ problems (e.g., ‘it is an incredibly complex and multidisciplinary issue’ (teacher of geography)). In both their climate change and climate change education descriptions, teachers only occasionally portray matters of social justice (more frequently in climate change than climate change education). Both climate change and climate change education conceptions emphasise individual action or behaviour change to address the crisis, more than collective action or structural measures—although the latter are mentioned by some teachers. Some teachers do emphasise the role of political structures in their climate change conceptions, but they are a minority (e.g., ‘a disgraceful calamity exacerbated by corporate and government greed’ (teacher of geography), and ‘the failure of governments’ and ‘a crisis that needs urgent action by governments and businesses’ (teacher of geography)). The reference to political structures is less prominent in their descriptions of climate change education. This echoes critiques of school geography that have focussed environmental processes over how societies work [43].

Many teachers’ conceptions of climate change include anger and blame around over-consumption and a failure to act—although it is not always clear toward whom that blame is directed (e.g., ‘the most avoidable, cataclysmic event in human history’ (teacher of geography)). Climate change education conceptions, by contrast, are less angry or apportioning blame and, therefore, it appears that teachers might be mediating their most negative conceptions of climate change.

Climate change education takes on a more factual approach to the Earth–atmosphere system knowledge about climate change, along with how young people’s individual actions and behaviours can help them feel more empowered. Some teachers mention the need for students to learn about climate change education across a range of subjects beyond geography (e.g., ‘a key topic which should be discussed across all subjects’ (teacher of geography), and ‘a fundamental part of lots of subjects and citizenship’ (teacher of geography)); this reflects findings in others’ research with teachers about the value of climate change being incorporated beyond geography and science curricula [7,8]. This is also consistent with the mix of disciplinary understandings alluded to in teachers’ conceptions of climate change, including Earth–atmosphere processes, human and natural systems, social–economic structures, social justice, and moral questions.

5.2. Teachers’ Conceptions of Sustainability and Sustainability Education

The dominance of the Brundtland definition of sustainable development [37] on the description of sustainability by teachers of geography is not unexpected, given that this definition is considered to be the most commonly used definition for school geography in England [44]. This raises questions about the influence of the ORF (Official Recontextualising Field) and PRF (Pedagogical Recontextualising Field), including GCSE specifications and textbooks, respectively.

There also appears to be a notable absence of any references to the UN’s [45] Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); this is surprising given the emphasis placed on education within the SDGs and the resources developed around this internationally and nationally (e.g., [46]). Though, as acknowledged by Healy et al. [47], within England, some geography textbook resources provide quite an uncritical and limited approach to introducing students to the SDGs; that, in part, is perceived as being understandable given the time lag between geographical research being undertaken and influencing knowledge and texts for teachers and teaching.

The teachers’ conceptions of sustainability also emphasised the future, and the responsibility of one human generation to protect the next (e.g., ‘the ability to protect our future generations’ (teacher of geography)). This suggests sustainability was conceived as mainly being about human survival and flourishing into the future. However, the natural environment and stewardship of planet Earth were frequently mentioned, with the implication that sustainability includes the intrinsic value of plants and animals (the more-than-human world). Sustainability as social justice was rarely expressed. The fact there were few responses that engaged with issues of ‘social justice’ appears to be notable given that environmental and social justice are seen as fundamental to understanding sustainability [48]. This indicates there is a disconnect between how the concept of sustainability is defined within the discipline of geography and in other related disciplines.

Many respondents emphasised that everyone needed to play a part (e.g., ‘everyone’s job’ (teacher of geography) and ‘a way for us all to become involved in ensuring that we move forwards and reduce the impact of climate change’ (teacher of geography)). It was not clear how far most teachers saw this as individual responsibility and action or collective responsibility and action. However, only a small number of teachers mentioned the role of social or economic structures in sustainability, suggesting that the other teachers might have seen this action and behaviour as primarily an individual’s responsibility. Some conceptions of sustainability included a critical dimension, such as the need to question the motivations of big corporations claiming to champion ‘sustainability’ (e.g., ‘a concept so vague that anyone can shape wording to make it sound like they are sustainable’ (teacher of geography)). Overall, however, the teachers did not emphasise the nature of sustainability as a wicked problem or a contested, problematic concept. ‘Hope’ emerged either explicitly or implicitly in many teachers’ conceptions of sustainability—a futures dimension (a vision of wellbeing for people and planet) to articulate the meaning of sustainability. However, it is hard to gauge how strongly the teachers believed that these sustainable futures will come to pass (e.g., ‘a shimmer of hope but that we will all need to work towards’ (teacher of geography)). Where teachers spoke more explicitly about hope, it tended to be portrayed as a tentative hope, or a chance we have for sustainable futures. This was not framed as optimism about the future, which is notable when reflecting on the way Dewey [49], p. 294, distinguishes hope from optimism, where optimism can lead to ‘fatalistic contentment’.

The teachers’ conceptions of sustainability education emphasised teaching the ‘three pillars’ or elements of environmental, economic, and social sustainability. These were described both as important knowledge in their own right, and as the areas students needed to consider in decision-making. Decision making and action were foregrounded by over half the respondents, suggesting that many teachers of geography think of sustainability education as including developing knowledge and young people’s capabilities (decision-making with the environmental, economic, and social models). The emphasis on balancing these three elements (pillars) contrasts somewhat with teachers’ conceptions of sustainability, which had a greater emphasis on environment and nature (as providing the resources for human survival) and relatively little emphasis on the social and economic factors. Borg et al. [28] similarly found that Swedish teachers placed different emphasis on the three elements, which included greater uncertainty in relation to economic sustainability. Consistent with their conceptions of climate change education, the teachers tended to see sustainability education as supporting young people towards responsible actions and behaviours as individuals. Conceptions of sustainability education rarely suggested understanding or the capacity to act collectively. Linked to this point, only a small minority of teachers conceived sustainability education as involving critical thinking about systems and structures that have led to a sustainability crisis and the capability to act collectively to regulate these systems, or adapt them to support more sustainable futures. Some teachers were explicit that sustainability education is an essential part of school geography, and this was implied by others. Some teachers pointed out the need for sustainability education to be spread across school subjects, which echoes findings of previous research with teachers [8,35]. However, the majority did not imply a fundamental connection between sustainability education and geography teaching, leaving open the question of how confident or certain teachers of geography feel about their role as sustainability educators within (or perhaps alongside) their role as teachers of geography.

5.3. Connections between Teachers’ Conceptions of Climate Change Eeducation and Sustainability Education

As set out in Section 2, studies typically place a focus on either climate change (education) or sustainability (education). Through our analysis, we have been able to identify possible connections between how these two distinct concepts have been articulated by the teachers of geography.

There appear to be several similarities between how climate change education and sustainability education have been described by the teachers of geography. This includes references to (i) how crucial these concepts are for young people, (ii) the ways in which this education supports young people making informed choices or to take specific actions, and (iii) how these concepts should be addressed across curricula via multiple subjects. Within their descriptions, teachers did not make reference to where climate change education and sustainability education could take place beyond the classroom, which has been recognised in other research with teachers [50].

Within sustainability education, there were references to certain pro-environmental behaviours (e.g., recycling), whereas teaching about and encouraging actions around specific pro-environmental behaviors were not prominent in responses about climate change education. Critical perspectives on climate change education and sustainability education were in the minority. For climate change education, teachers considered the limitations around the lack of curriculum time for climate change education and the complexity of climate change as a problem, and the criticality needed to enable children and young people to understand that climate change does not just require individual action. For sustainability education, the limitations focussed more specifically on the ways in which sustainability education was seen to offer only a limited way of addressing the problem of climate change.

5.4. Limitations of This Research

We recognise there are methodological limitations to our research. As we mentioned in Section 3, the survey respondents are not a representative sample of all teachers of geography, but a self-selecting sample who are likely to be teachers who are more interested in climate change and sustainability education. The order of questions may affect responses, and our inductive coding strategy cannot completely remove researcher subjectivity. Our analysis is, to an extent, an interpretation of these data. We are drawing on teachers’ descriptions of the concepts partly as a way to understand their engagement with debates around climate change and sustainability education, including from within the disciplinary and subject education community of geography. We do not draw on any additional survey data—for example, where the teachers reported how they incorporated climate change and sustainability within their teaching. These additional data may provide different insights into how teachers are engaging with these concepts in practice [51].

6. Conclusions

To conclude, we now address three interconnected points that come from teachers’ descriptions of climate change (education) and sustainability (education): (i) a disconnect between policy and rhetoric, (ii) a lack of attention to social and environmental justice, and (iii) an over-focus on individual action.

Some of the teachers of geography’s conceptions appear to be ‘stuck in time’—the prevalence of the Brundtland definition of sustainable development epitomises this [36]. This, alongside a lack of recognition of some of the ways in which sustainability and climate change as concepts have been developed within academic research and professional practice (including a stronger focus on social and environmental justice), indicates a possible disconnect between the knowledge teachers draw upon within school geography and the ambitions for a Future 3 curriculum for geography [51]. The Future 3 curriculum scenario argues for ‘productive engagement (by teachers and students)’ whilst ‘new knowledge is produced in specialised communities, including ever-changing academic disciplines’ [52], p. 183, and is built upon Young and Muller’s exploration of three scenarios for the future of education and their implications for curricula, knowledge, and school subjects [53]. There were few conceptions that indicated teachers held ‘productive engagement’ with the ways in which knowledge about and for climate change and sustainability education have changed in the last decade. In particular, the lack of attention to social and environmental justice appears especially problematic, given the racio-colonial legacies shaping how climate change is differentially experienced [54]. The apparent lack of productive engagement with the discipline of geography is consistent with the policy disconnect between international imperatives (the Sustainable Development Goals/UNESCO’s ‘Transforming Our World’ educational agenda) and the reality of the enacted curriculum in the English school system, in which teacher performativity for exam results can dominate and squeeze out opportunities for deeper engagement with geography, which is needed for ‘Future 3’ curriculum development [15,26,45]. National curricula and external examination specifications have tended to encourage an atomized approach to knowledge —as a series of topics that can seem disconnected, with small pieces of information to be learned, rather than the development of understanding bigger concepts like ‘environment’, ‘place’ and ‘Earth systems’ [55] and replacing disconnected, ‘mechanistic thinking’ with holistic or ‘ecological thinking’ [56]. We suggest there ought to be more work to explore whether there is an ‘over-focus’ on individual action in climate change and sustainability education.

Whilst there were references to the importance of sustainability and climate change within the subject of geography, and specifically the value of sustainability as an ‘underpinning concept’, there was not any other explicit reference to debates from the disciplinary community of geography. Knowledge and scholarship within geography, and geography education around the political economy and racial capitalism, might enable more critical framings of structural changes that are required within political–economic systems to address climate change and take sustainability forward [57,58,59].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W.; methodology G.H., D.M. and N.W.; formal analysis, G.H., D.M. and N.W.; investigation, G.H., D.M. and N.W.; data curation, G.H., D.M. and N.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H., D.M. and N.W.; writing—review and editing, G.H., D.M. and N.W.; funding acquisition, N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University College London IOE Strategic Investment Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the BERA ethical guidelines and approved by UCL Research Ethics Committee (REC 1627, 35/05/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Thedatasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to n.walshe@ucl.ac.uk.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kate Greer, Richard Sheldrake, and Alison Kitson within the UCL Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability Education for their support with the development, administration, and broader analysis of the teacher survey. We are grateful for the constructive comments that the reviewers provided on earlier versions of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Taylor, M.; Watts, J.; Bartlett, J. Climate Crisis: 6 Million People Join Latest Wave of Global Protests. The Guardian 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/27/climate-crisis-6-million-people-join-latest-wave-of-worldwide-protest (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Teach the Future. Our Research. Available online: https://www.teachthefuture.uk/research (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Greer, K.; Sheldrake, R.; Rushton, E.; Kitson, A.; Hargreaves, E.; Walshe, N. Teaching Climate Change and Sustainability: A Survey of Teachers in England; University College London: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). Geography Programmes of Study; Department for Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). The National Curriculum in England Key Stages 3 and 4 Framework Document; Department for Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). GCSE Subject Content for Geography; Department for Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, V.; Eilam, E.; Tolppanen, S.; Assaraf, O.B.Z.; Gokpinar, T.; Goldman, D.; Putri, G.A.P.E.; Subiantoro, A.W.; White, P.; Widdop Quinton, H. A Cross-Country Comparison of Climate Change in Middle School Science and Geography Curricula. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2022, 44, 1379–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jones, P.; Sands, D.; Dillon, J.; Fenton-Jones, F. The views of teachers in England on an action-oriented climate change curriculum. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Teaching Council for Scotland [GTCS]. Learning for Sustainability. Available online: https://www.gtcs.org.uk (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Welsh Assembly Government. Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship: A Common Understanding for Schools. Available online: https://hwb.gov.wales/api/storage/eaf467e6-30fe-45c9-93ef-cb30f31f1c90/common-understanding-for-school.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- UNESCO. United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: International Implementation Scheme; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992. AGENDA 21. 1992. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- UNESCO/UNEP. Climate Change Starter’s Guidebook: An Issues Guide for Education Planners and Practitioners; UNESCO/UNEP: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Shaping the Education of Tomorrow: 2012 Full-Length Report on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Department for Education and Skills (DfES). National Framework for Sustainable Schools; DfES: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education and Skills (DfES). National Curriculum; DfES: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF). Planning a Sustainable School: Driving School Improvement through Sustainable Development; Department for Children, Schools and Families: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy; Crown: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sustainability-and-climate-change-strategy/sustainability-and-climate-change-a-strategy-for-the-education-and-childrens-services-systems (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Hammond, L.; Healy, G.; Tani, S.; Bladh, G. National Curricula: Reflecting on Powers, Possibilities and Constraints of National Geography Guidelines in England, Finland and Sweden. J. Curric. Stud. 2024; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Board of Education (FNBE). National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014; Finnish National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Agency for Education (FNAfE). National Core Curriculum for General Upper Secondary Schools; Finnish National Agency for Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huckle, J. Critical Education for Sustainability and Chantal Mouffe’s Green Democratic Revolution. Curric. J. 2024, 35, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawding, C. Constructing the Geography Curriculum. In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning; Butt, G., Ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, L.; Rushton, E.A.C. Putting climate change at the heart of education: Is England’s strategy a placebo for policy? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 1083–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. Hyper-Socialised—Enacting the Geography Curriculum in Late Capitalism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, M.; Corney, G.; Childs, A. Student Teachers’ Conceptions of Sustainable Development: The Starting-Points of Geographers and Scientists. Educ. Res. 2004, 46, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Gericke, N.; Höglund, H.-O.; Bergman, E. Subject- and Experience-Bound Differences in Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz Fındık, L.; Bayram, I.; Canaran, Ö. Pre-service English Language Teachers’ Conceptions of Sustainable Development: A Case from Turkish Higher Education Context. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 423–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratinen, I.J. Primary Student-Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of the Greenhouse Effect: A Mixed Method Study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 929–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D. Conceptualizing In-Service Secondary School Science Teachers’ Knowledge Base for Promoting Understanding about the Science of Global Climate Change. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sund, P.; Gericke, N. Teaching Contributions from Secondary School Subject Areas to Education for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Study of Science, Social Science and Language Teachers. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 772–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltner, E.-M.; Scharenberg, K.; Hörsch, C.; Rieß, W. What Teachers Think and Know about Education for Sustainable Development and How They Implement It in Class. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, R.K.; Reid, A. Beginning Scottish Geography Teachers’ Perceptions of Education for Sustainable Development. In Developing Critical Perspectives on Education for Sustainable Development/Global Citizenship in Initial Teacher Education; UK Teacher Education Sustainable Development/Global Citizenship (UK TE ESD/GC): London, UK, 2009; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Väänänen, N.; Vartiainen, L.; Kaipainen, M.; Pitkäniemi, H.; Pöllänen, S. Understanding Finnish Student Craft Teachers’ Conceptions of Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 963–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Sass, W.; Boeve-de Pauw, J. Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability: The Theoretical Grounding and Empirical Validation of a Novel Concept. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 742–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlee, F. A World on the Edge of Climate Disaster. BMJ 2021, 375, n2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Powell, R.A. The Climate Crisis and the Rise of Eco-Anxiety. BMJ Opinion. 6 October 2021. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/10/06/the-climate-crisis-and-the-rise-of-eco-anxiety/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Wu, J.; Snell, G.; Samji, H. Climate Anxiety in Young People: A Call to Action. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e435–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnegan, W. Educating for Hope and Action Competence: A Study of Secondary School Students and Teachers in England. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 1617–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. Teaching Secondary Geography as If the Planet Matters; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, N. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Environmental and Sustainability Education: Developing Geography Students’ Understandings of Sustainable Development Using Poetry. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1130–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Global Dimension. The Global Learning Programme. Available online: https://globaldimension.org.uk/the-global-learning-programme (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Healy, G.; Laurie, N.; Hope, J. Creating Stories of Educational Change in and for Geography: What Can We Learn from Bolivia and Peru? Geography 2023, 108, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J. Just Sustainabilities: Policy, Planning and Practice; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. The Middle Works, 7: 1912–1914: [Essays, Book Reviews, Encyclopedia Articles in the 1912–1914 Period, and Interest and Effort in Education]; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, E.A.; Dunlop, L.; Atkinson, L. Fostering Teacher Agency in School-Based Climate Change Education in England, UK. Curric. J, 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, G.; Walshe, N.; Mitchell, D. Teachers’ perspectives and practices of climate change and sustainability education in primary and secondary school geography in England. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2024; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J.; Lambert, D. Race, Racism and the Geography Curriculum; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.; Muller, J. Three Educational Scenarios for the Future: Lessons from the sociology of knowledge. Eur. J. Educ. 2010, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F. Climate Change, COVID-19, and the Co-Production of Injustices: A Feminist Reading of Overlapping Crises. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 22, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geographical Association. A Framework for the School Geography Curriculum; Geographical Association: Sheffield, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, S. Learning and Sustainability in Dangerous Times: The Stephen Stirling Reader; Agenda Publishing Limited: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, G. Rethinking Racial Capitalism: Questions of Reproduction and Survival; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.; Habib, B.; Harris, S.; Whittall, D.; Winter, C. Racial Capitalism and the School Geography Curriculum. Teach. Geogr. 2022, 47, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. Culture and the Political Economy of Schooling: What’s Left for Education? Routledge: Abingdon, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).