Transformative Social Innovation as a Guideline to Enhance the Sustainable Development Goals’ Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Recommitment of governments to seven years of accelerated, sustained, and transformative action, both nationally and internationally;

- -

- Advances in concrete, as well as integrated and targeted policies and actions to eradicate poverty, reduce inequality and end the war on nature, with a focus on advancing the rights of women and girls and empowering the most vulnerable;

- -

- Strengthening of national and subnational capacity, accountability, and public institutions to deliver accelerated progress towards achieving the SDGs;

- -

- Recommitment of the international community to mobilize the resources and investment needed for developing countries to achieve the SDGs, particularly those in special situations and experiencing acute vulnerability;

- -

- Member States should facilitate the continued strengthening of the UN development system and boost the capacity of the multilateral system to tackle emerging challenges and address SDG-related gaps and weaknesses.

2. Innovation and Transformative Change

3. Development Measures

4. Searching for Improvements in the SDGs’ Implementation

4.1. Methodological Steps

4.2. United Nations’ Propositions on Participation and Partnerships to Foster the SDGs

4.3. SDGs Organized in a Process-Oriented View

4.4. TSI and SDGs: A Systematic Literature Review

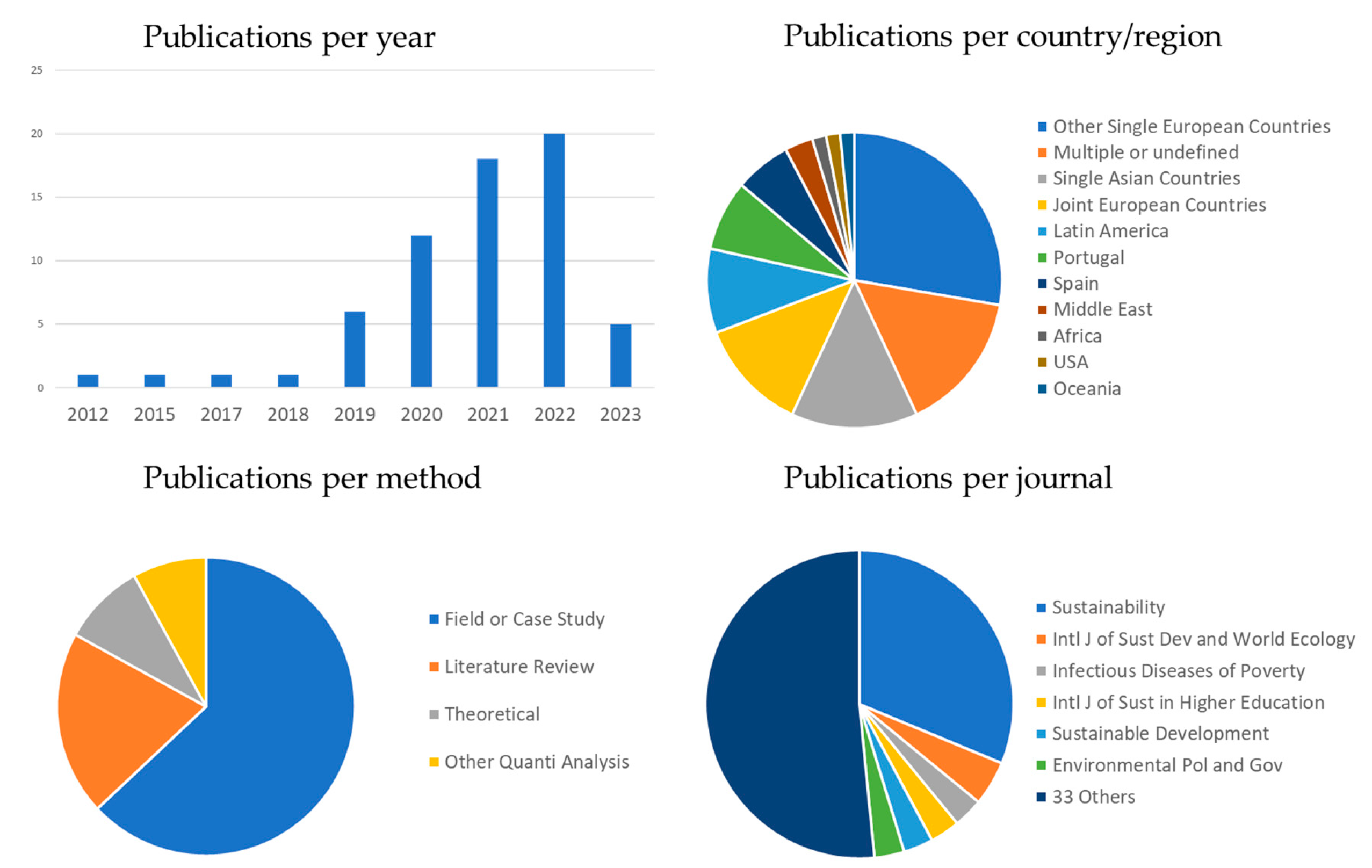

4.5. Results

- Capacity building for sustainable practices is fundamental to create a more sustainable culture and drive adaptation and systemic transformation [110,118,124], which is being developed through learning and transdisciplinary programs, in universities [82,83,84,86,87], and in communities [39,81,88,104,105,107];

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Love, P. (Ed.) Debate the Issues: New Approaches to Economic Challenges; OECD Insights; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus: March 2024 Is the Tenth Month in a Row to Be the Hottest on Record. March Climate Bulletins—Newsflash. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-march-2024-tenth-month-row-be-hottest-record (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Riddel, R.; Ahmed, N.; Maitland, A.; Lawson, M.; Taneja, A. Inequality Inc. How Corporate Power Divides Our World and the Need for a New Era of Public Action; Oxfam International: Oxford, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/inequality-inc (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Wallace-Wells, D. The Uninhabitable Earth; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; UN-Dokument A/42/427; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, I. Equitable Development on a Healthy Planet–Transition Strategies for the 21st Century. Synthesis report for discussion. In Proceedings of the Our Hands: United Nations Earth Summit ’92: Report of the The Hague Symposium on Sustainable Development: From Concept to Action, Hague, The Netherlands, 25–27 November 1991; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/193326?ln=en&v=pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Zen and the Triple Bottom Line. Available online: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/zen-and-triple-bottom-line (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- The Economist. The Fundamental Contradiction of ESG Is Being Laid Bare. Sep 29th 2022. Available online: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/09/29/the-fundamental-contradiction-of-esg-is-being-laid-bare?utm_source=flipboard&utm_content=TheEconomist%2Fmagazine%2FLeaders (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Lönngren, J.; van Poeck, K. Wicked problems: A mapping review of the literature. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition—July 2023; UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L.; Trevisan, L.V.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Brandli, L.L.; Sierra, J.; Salvia, A.L.; Pretorius, R.; Nicolau, M.; et al. When the alarm bells ring: Why the UN sustainable development goals may not be achieved by 2030. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 407, 137108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD and Eurostat. Oslo Manual 2018; OECD: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/science/oslo-manual-2018-9789264304604-en.htm (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Oxford University; New York, NY, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A. Innovation, Sustainability and Democracy: An Analysis of Grassroots Contributions. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2018, 6, 64–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L.; Zawdie, G. The triple helix perspective of innovation systems. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 22, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Etzkowitz, H. Triple Helix Twins: A Framework for Achieving Innovation and UN Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krlev, G.; Anheier, H.; Mindelberger, G. Social Innovation—What is it and who makes it? In Social Innovation: Comparative Perspectives; Anheier, H., Krlev, G., Mildenberger, G., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Social Innovation Research in the European Union. Approaches, Findings and Future Directions: Policy Review; Jenson, J., Harrisson, D., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J. How social innovation underpins sustainable development. In Atlas of Social Innovation: New Practices for a Better Future; Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Schröder Zirngiebl, M., Eds.; Technische Universität Dortmund: Essen, Germany, 2018; pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, E.; Ville, S. Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickiene, S.; Tamasauskiene, Z. Social Innovation for Sustainable Development. In Innovations and Traditions for Sustainable Development; World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Krasnov, E., Gaeva, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeier, S. Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research? Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, G.; Schwarz, G. What Sustainable Development Goals Do Social Innovations Address? A Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Social Innovation Literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEPA 2011—Bureau of European Policy Advisers (BEPA). Empowering People, Driving Change. Social Innovation in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifácio, M. Social innovation: A novel policy stream or a policy compromise? An EU perspective. Eur. Rev. 2014, 22, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unceta, A.; Castro-Spila, J.; Fronti, J. Social innovation indicators. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 29, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. The International Handbook on Social Innovation. Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Santha, S. Critical Transitions in Social Innovation and Future Pathways to Sustainable Development Goals. The Indian Context. IJSW 2019, 80, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Future is Now. Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. 2019, p. 30. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/24797GSDR_report_2019.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxeltine, A.; Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Kunze, I.; Longhurst, N.; Dumitru, A.; O’Riordan, T. Conceptualising the role of social innovation in sustainability transformations. In Social Innovation and Sustainable Consumption. Research and Action for Societal Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Henfrey, T.; Feola, G.; Penha-Lopes, G.; Sekulova, F.; Esteves, A.M. Rethinking the sustainable development goals: Learning with and from community-led initiatives. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krlev, G.; Bund, E.; Mildenberger, G. Measuring What Matters—Indicators of Social Innovativeness on the National Level. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2014, 31, 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Millenium Goals (MGDs). Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Fukuda-Parr, S. From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: Shifts in purpose, concept, and politics of global goal setting for development. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDESA. Partnership Platforms for the SDGs: Learning from Practice. Dave Prescott and Darian Stibbe, The Partnering Initiative, and UNDESA. 2020. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/2699Platforms_for_Partnership_Report_v0.92.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Stiglitz, J.M.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/documents/rapport_anglais.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Martin-Breen, P.; Anderies, J.M. Resilience: A Literature Review; Bellagio Initiative; IDS: Brighton, UK, 2011; Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/3692/Bellagio-Rockefeller%20bp.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/#goal_section (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Global Innovation Index. Available online: https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/Home (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Social Progress Index. Available online: https://www.socialprogress.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- World Happiness Index. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Gross National Happines. Available online: https://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- World Governance Indicators. Available online: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Stuart, E.; Woodroffe, J. Leaving No-one Behind: Can the Sustainable Development Goals Succeed Where the Millennium Development Goals Lacked? Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Rockström, J.; Raskin, P.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C.; Smith, A.; Thompson, J.; Millstone, E.; Ely, A.; Arond, E.; et al. Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Environment Outlook GEO-6: Healthy Planet, Healthy People; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-6 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- UNDESA. Maximising the Impact of Partnerships for the SDGs; Stibbe, D.T., Reid, S., Gilbert, J., Eds.; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2564Maximising_the_impact_of_partnerships_for_the_SDGs.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- UNDESA. The SDG Partnership Guidebook: A Practical Guide to Building Highimpact Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals; Stibbe, D., Prescott, D., Eds.; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, H.J. Introduction to Administrative Business Process Improvement. In Business Process Improvement Workbook: Documentation, Analysis, Design and Management of Business Process Improvement; Harrington, H.J., Esseling, E., Van Nimwegen, H., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluations and Results Based Management. 2010. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/glossaryofkeytermsinevaluationandresultsbasedmanagement.htm (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Willaert, P.; Van den Bergh, J.; Willems, J.; Deschoolmeester, D. The Process-Oriented Organisation: A Holistic View—Developing a Framework for Business Process Orientation Maturity. In Business Process Management: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, BPM, 2007, Brisbane, Australia, 24–28 September 2007; Alonso, G., Dadam, P., Rosemann, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkki, S.; Dalla Torre, C.; Fransala, J.; Živojinović, I.; Ludvig, A.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Melnykovych, M.; Sfeir, P.R.; Arbia, L.; Bengoumi, M.; et al. Reconstructive Social Innovation Cycles in Women-Led Initiatives in Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel, U.; Becker, N.; Trapp, M.; Speck, M. Assessing the Contribution of Innovative Technologies to Sustainable Development for Planning and Decision-Making Processes: A Set of Indicators to Describe the Performance of Sustainable Urban Infrastructures (ISI). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, G.; Erdin, C. Evaluation of smart and sustainable cities through a hybrid MCDM approach based on ANP and TOPSIS technique. Heliyon 2020, 6, e0505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Beeton, R.; Sigler, T.; Halog, A. Enhancing the adaptive capacity for urban sustainability: A bottom-up approach to understanding the urban social system in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 235, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhani, R. Understanding Private-Sector Engagement in Sustainable Urban Development and Delivering the Climate Agenda in Northwestern Europe—A Case Study of London and Copenhagen. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- "Pires, S.; Fidélis, T. A proposal to explore the role of sustainability indicators in local governance contexts: The case of Palmela, Portugal. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 23, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikologianni, A.; Betta, A.; Pianegonda, A.; Favargiotti, S.; Moore, K.; Grayson, N.; Morganti, E.; Berg, M.; Ternell, A.; Ciolli, M.; et al. New Integrated Approaches to Climate Emergency Landscape Strategies: The Case of Pan-European SATURN Project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.; Marques, J.F.; Pinto, H. Intentional sustainable communities and sustainable development goals: From micro-scale implementation to scalability of innovative practices. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 67, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. Social Innovation Governance in Smart Specialisation Policies and Strategies Heading towards Sustainability: A Pathway to RIS4? Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, N.; Nangia, C.; Adhvaryu, B. Achieving Localization of SDG11: A critical review of South Asian region and learnings for India. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. B Plan. Anal. Simul. 2023, 11, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, Y.; Prim, M.; Dandolini, G. Educating City: A Media for Social Innovation. In Proceedings of the IDEAS 2019: The Interdisciplinary Conference on Innovation, Design, Entrepreneurship, and Sustainable Systems; Pereira, L., Carvalho, J.R., Kruss, P., Klofsten, M., De Negri, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, A.; Costa, C. Integrating Communities into Tourism Planning Through Social Innovation. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 12, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini Govigli, V.; Alkhaled, S.; Arnesen, T.; Barlagne, C.; Bjerck, M.; Burlando, C.; Melnykovych, M.; Fernandez-Blanco, C.R.; Sfeir, P.; Górriz-Mifsud, E. Testing a Framework to Co-Construct Social Innovation Actions: Insights from Seven Marginalized Rural Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Smart Rural Communities: Action Research in Colombia and Mozambique. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baena, J.; García-Serrano, J.d.D.; Toro-Peña, O.; Vela-Jiménez, R. The Influence of the Organizational Culture of Andalusian Local Governments on the Localization of Sustainable Development Goals. Land 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G. A sustainable model for small towns and peripheral communities: Converging elements and qualitative analysis. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirambo, D. Can Social Innovation Address Africa’s Twin Development Challenges of Climate ChangeVulnerability and Forced Migrations? J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 7, 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dryjanska, L.; Kostalova, J.; Vidovic, D. Higher Education Practices for Social Innovation and Sustainable Development. In Social Innovation in Higher Education, Innovation, Technology, and Knowledge Management; Păunescu, C., Lepik, K.-L., Spencer, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, C.; Fabra, M.E.; Mason, C.; Puente-Rueda, C.; Sáenz-Nuño, M.A.; Viñuales, R. Role of the Universities as Drivers of Social Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M.; Henriksen, H.; Spengler, J. Universities as the engine of transformational sustainability toward delivering the sustainable development goals: “Living labs” for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, G.; Segalàs, J.; Barrón, A.; Fernández-Morilla, M.; Fuertes, M.T.; Ruiz-Morales, J.; Gutiérrez, I.; García-González, E.; Aramburuzabala, P.; Hernández, A. Didactic Strategies to Promote Competencies in Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, C.; Silva, J.; Calheiros, C.S.C.; Mikusinski, G.; Iwinska, K.; Skaltsa, I.G.; Krakowska, K. Teaching Sustainable Development Goals to University Students: A Cross-Country Case-Based Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Ho, S.-J.; Huang, T.-C. The Development of a Sustainability-Oriented Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship Education Framework: A Perspective Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Castañon, L.; Romero-Ugalde, M. Training of communities of sustainability practice through science and art. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Zubiaur, M.; Torres-Bustos, H.; Arroyo-Vázquez, M.; Ferrer-Gisbert, P. Promotion of Social Innovation through Fab Labs. The Case of ProteinLab UTEM in Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Zermeño, M.G.; Aleman de la Garza, L.Y. Open laboratories for social innovation: A strategy for research and innovation in education for peace and sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez-Figueroa, J.A.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.; García-Peñalvo, F. Social innovation laboratories for the social construction of knowledge: Systematic review of literature. Texto Livre 2021, 14, e33750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruvot, F.; Dupont, L.; Morel, L. Collaborative networks between innovation spaces. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 28th International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) & 31st International Association For Management of Technology (IAMOT) Joint Conference, Nancy, France, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Altieri, B.; Hutchinson, T.; Harris, A.J.; McLean, D. Design for Social Innovation: A Systemic Design Approach in Creative Higher Education toward Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, N.; Graybeal, G. Learning Design Thinking: A Social Innovation Jam. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2022, 5, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, R.; Qaed, F. Service Design Thinking and Social Innovation Sustainability. In Proceedings of the 2020 Second International Sustainability and Resilience Conference: Technology and Innovation in Building Designs, Sakheer, Bahrain, 11–12 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Krittayaruangroj, K.; Iamsawan, N. Sustainable Leadership Practices and Competencies of SMEs for Sustainability and Resilience: A Community-Based Social Enterprise Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echaubard, P.; Thy, C.; Sokha, S.; Srun, S.; Nieto-Sanchez, C.; Grietens, K.; Juban, N.; Mier-Alpano, J.; Deacosta, S.; Sami, M.; et al. Fostering social innovation and building adaptive capacity for dengue control in Cambodia: A case study. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, L.; Manderson, L.; Balabanova, D. The application of social innovation in healthcare: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvo, L.; Pastore, L.; Antonelli, A.; Petruzzella, D. Social impact and sustainability in short food supply chains: An experimental assessment tool. New Medit 2021, 3, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, L.; Belliggiano, A. A Highly Condensed Social Fact: Food Citizenship, Individual Responsibility, and Social Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D.; Blanke, M. Smallholder farmers as a backbone for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 27, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsete, E.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Nijnik, M.; Marini-Govigli, V.; Koundouri, P.; Kafetzis, A. Social innovation for developing sustainable solutions in a fisheries sector. Environ. Pol. Gov. 2022, 32, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, M. Learning urban energy governance for system innovation: An assessment of transformative capacity development in three South Korean cities. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2018, 21, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.V.; Segers, J.P.; Herlaar, R.; Richt Hannema, A. Trends in Sustainable Energy Innovation—Transition Teams for Sustainable Innovation. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 10, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardinger, L.; Andrade, M.; Correa, M.; Turra, A. Crafting a sustainability transition experiment for the brazilian blue economy. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlagne, C.; Melnykovych, M.; Miller, D.; Hewitt, R.J.; Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Nijnik, M. What Are the Impacts of Social Innovation? A Synthetic Review and Case Study of Community Forestry in the Scottish Highlands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, A.S.N.; Alperstedt, G.D.; Andion, C. Social Innovation Ecosystem and Preservation of the Atlantic Forest in Southern Brazil: The Case Araucária+. RGO—Rev. Gestão Organ. 2023, 16, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadabadi, A.; Mirzamani, A. The sustainable development goals and leadership in public sector: A case study of social innovation in the disability sector of Iran. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 36, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.R.A.; Bohensky, E.L.; Suadnya, W.; Yanuartati, Y.; Handayani, T.; Habibi, P.; Puspadi, K.; Skewes, T.D.; Wise, R.M.; Suharto, I.; et al. Scenario planning to leap-frog the Sustainable Development Goals: An adaptation pathways approach. Clim. Risk Manag. 2016, 12, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masselot, C.; Jeyaram, R.; Tackx, R.; Fernandez-Marquez, J.L.; Grey, F.; Santolini, M. Collaboration and Performance of Citizen Science Projects Addressing the Sustainable Development Goals. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2023, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Kivimaa, P.; Ramirez, M.; Schot, J.; Torrens, J. Transformative outcomes: Assessing and reorienting experimentation with transformative innovation policy. Sci. Public Policy 2021, 48, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jütting, M. Exploring Mission-Oriented Innovation Ecosystems for Sustainability: Towards a Literature-Based Typology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, N.; TyreeHageman, J.; Kele, J. Beyond Agenda 2030: Future-Oriented Mechanisms in Localising the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Ferreira, C.; Araújo, M.; Lopes Nunes, M.; Ferreira, P. Social innovation projects link to sustainable development goals: Case of Portugal. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini Govigli, V.; Rois-Díaz, M.; den Herder, M.; Bryce, R.; Tuomasjukka, D.; Gorriz-Mifsud, E. The green side of social innovation: Using sustainable development goals to classify environmental impacts of rural grassroots initiatives. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Fritzen, B.; Ruiz Vargas, V.; Paço, A.; Zhang, Q.; Doni, F.; Azul, A.M.; Vasconcelos, C.R.P.; Nikolaou, I.E.; Skouloudis, A.; et al. Social innovation for sustainable development: Assessing current trends. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, E.S.; Zamzuri, N.H.; Jalil, S.A.; Salleh, S.M.; Mohamad, A.; Rahim, R.A. A Social Innovation Model for Sustainable Development: A Case Study of a Malaysian Entrepreneur Cooperative (KOKULAC). Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Ferreira, C.; Araújo, M.; Nunes, M.L.; Ferreira, P. Understanding the Linkage Between Social Innovation and Sustainable Development Goals: Some Insights of Field Research. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 13–16 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntjens, P. Towards a Natural Social Contract. Transformative Social Ecological Innovation for a Sustainable, Healthy and Just Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, P.; Imas, M. Decision support for social innovation enabling sustainable development. J. Decis. Syst. 2022, 31 (Suppl. 1), 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidet, E.; Richez-Battesti, N. The Trajectories of Institutionalisation of the Social and Solidarity Economy in France and Korea: When Social Innovation Renews Public Action and Contributes to the Objectives of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Razzaque, J.; McElwee, P.; Turnhout, E.; Kelemen, E.; Rusch, G.M.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Chan, I.; Lim, M.; Islar, M.; et al. Transformative governance of biodiversity: Insights for sustainable development. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 53, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapke, N.; Omann, I.; Wittmayer, J.; Van Steenbergen, F.; Mock, M. Linking Transitions to Sustainability: A Study of the Societal Effects of Transition Management. Sustainability 2017, 9, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M. ‘Don’t call me resilient again!’: The New Urban Agenda as immunology… or… what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with ‘smart cities’ and indicators. Environ. Urban. 2017, 29, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, S.; Jones, A.; Ward, J.; Christie, I.; Druckman, A.; Lyon, F. A Critical Review of the Role of Indicators in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, C.; Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. The Promise of Transformative Investment: Mapping the Field of Sustainability Investing. Deep Transitions Working Paper Series (DT2021-11). Available online: https://deeptransitions.net/publication/the-promise-of-transformative-investment-mapping-the-field-of-sustainability-investing/ (accessed on 27 September 2023).

|

|

| Correspondence to Conventional Strategic Map | Development Perspectives of the SDGs’ Strategic Map | SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Financial/ Shareholder value | Development Impacts/ Long Term Results/ Stakeholder value | 3. Well-being |

| 16. Peace and justice | ||

| 13. Global climate | ||

| 10. Reduced inequalities | ||

| 1. No poverty | ||

| Customers | Development Outcomes/ Middle Term Results | 3. Good health |

| 2. Zero hunger | ||

| 8. Sustainable economic growth | ||

| 11. Sustainable cities and communities | ||

| 14. Life below water | ||

| 15. Life on land | ||

| 7. Affordable and clean energy | ||

| 6. Clean water and sanitation | ||

| Internal Processes | Development Outputs/ Process Results | 12. Sustainable consumption |

| 12. Sustainable production | ||

| 2. Sustainable agriculture | ||

| 9. Sustainable industry, innovation and infrasctructure | ||

| 8. Decent work | ||

| Learning and Knowledge | Development Inputs/ Culture, Learning/ Governance | 13. Climate action |

| 16. Strong institutions | ||

| 17. Means of implementation | ||

| 17. Partnerships | ||

| 5. Gender equality | ||

| 4. Quality education |

| Abbreviation | Search String | Returned | Selected by Titles | Selected by Abstract | Selected after Full Reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSI | “transformative social innovation” AND (“sustainable development goals” OR “sdg*”) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| TI | “transformative innovation” AND (“sustainable development goals” OR “sdg*”) | 18 | 13 | 8 | 5 |

| SI | “social innovation” AND (“sustainable development goals” OR “sdg*”) | 167 | 99 | 58 | 40 |

| Generic | (“sustainab*” AND “innovat*” AND “governance” AND (“indicator” OR “assessment” OR “performance” OR “evaluat*”) AND (“territory*” OR “regional” OR “local”) | 87 | 87 | 39 | 18 |

| Total | 274 | 200 | 106 | 64 |

| Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) Smart urban, rural, and regional landscapes; community development; localization of SDGs | [39,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Education (SDG 4) | |

| Role of universities | [82,83,84,85,86,87] |

| Sustainability labs | [88,89,90,91,92] |

| Design thinking methods | [93,94,95] |

| Sustainable leadership competencies | [96] |

| Health (SDG 3) | [97,98] |

| Food production (SDG 12) | |

| Food supply chains | [99,100,101] |

| Smallholder farming | [102,103] |

| Energy (SDG 7) | [104,105] |

| Life below water (SDG 14) | [106] |

| Gender (SDG 5) | [63] |

| Governance, Institutions, Means of Implementation (SDG 16/SDG 17) | [23,79,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114] |

| Development Inputs/Culture, Learning/Governance | 13. Climate action | 17. Partnerships |

| 16. Strong institutions | 5. Gender equality | |

| 17. Means of implementation | 4. Quality education | |

| Governance and Impact on Public Policies | Government leadership for sustainability | |

| Long-term sustainability planning in practice | ||

| Social practices reconfigured | ||

| Systemic view by governments | ||

| Secondary Results Expected—Outcomes | Inclusive governance and decision making | |

| Social capital increased | ||

| Shared view developed | ||

| Primary Results Expected—Outputs | Stakeholder proactive engagement | Participation culture enhanced |

| Empowerment | Broadness of participation | |

| Systemic view | Depth of interactions | |

| Sustainable culture enhanced | ||

| Basic Activities | Capacity building for sustainability | |

| Communication tools and methods for participation | ||

| Stakeholder mapping and inclusiveness of all | ||

| Local leadership, social entrepreneurship | ||

| TARGETS | INDICATORS |

|---|---|

| 4.7—By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development 13.3—Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning | 4.7.1/13.3.1—Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education and (d) student assessment |

| 16.7—Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels | 16.7.1—Proportions of positions in national and local institutions, including (a) the legislatures; (b) the public service; and (c) the judiciary, compared to national distributions, by sex, age, persons with disabilities and population groups |

| 16.7.2—Proportion of population who believe decision-making is inclusive and responsive, by sex, age, disability, and population group | |

| 17.16—Enhance the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology, and financial resources, to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in all countries, in particular developing countries | 17.16.1—Number of countries reporting progress in multi-stakeholder development effectiveness monitoring frameworks that support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals |

| 17.17—Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships | 17.17.1—Amount in United States dollars committed to public-private partnerships for infrastructure |

| Suggested Indicators | Related SDG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and Impact on Public Policies | Degree of acceleration for achieving the SDGs | General | ||

| Money invested in sustainability public policies linked to the SDGs | 17.17 | |||

| Money invested in institutional strengthening and educational programs towards participation | 4.7 | 13.3 | 17.17 | |

| Number of multistakeholder sustainability plans and degree of execution | 17.16 | |||

| Secondary Results Expected—Outcomes | % of public policies directly related to the SDGs | 4.7 | ||

| Number of sustainability public policies created with the support of inclusive governance institutions | 16.7 | 17.16 | ||

| Institutional density, measured by quantity and quality of institutional relations | 16.7 | 17.16 | ||

| Primary Results Expected—Outputs | % of decisions originating from proposals by civil society actors | 16.7 | ||

| Active presence and deliberation of all important stakeholders in the meetings of deliberative instances | 16.7 | 17.7 | ||

| Basic Activities | % of local civil society representation in the composition of deliberative instances | 16.7 | ||

| % of local civil society representation in the constitution of deliberative instances | 16.7 | |||

| Number of people concluding capacitation to participation culture by origin (civil society, private sector, public sector in micro, regional and national scales) | 4.7 | 13.3 | 16.7 | |

| Number of people concluding capacitation to sustainable culture by origin (civil society, private sector, public sector in micro, regional and national scales) | 4.7 | 13.3 | 16.7 | |

| Number of people concluding capacitation to social entrepreneurship by origin (civil society, private sector, public sector in micro, regional and national scales) | 4.7 | 13.3 | 16.7 | |

| Development of efficient communication tools by number of institutional connections and remote deliberations | 16.7 | 17.16 | ||

| Money invested in institutional strengthening and educational programs towards participation and sustainability | 4.7 | 13.3 | 17.17 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pamplona, L.; Estellita Lins, M.; Xavier, A.; Almeida, M. Transformative Social Innovation as a Guideline to Enhance the Sustainable Development Goals’ Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167114

Pamplona L, Estellita Lins M, Xavier A, Almeida M. Transformative Social Innovation as a Guideline to Enhance the Sustainable Development Goals’ Framework. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167114

Chicago/Turabian StylePamplona, Leonardo, Marcos Estellita Lins, Amanda Xavier, and Mariza Almeida. 2024. "Transformative Social Innovation as a Guideline to Enhance the Sustainable Development Goals’ Framework" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167114

APA StylePamplona, L., Estellita Lins, M., Xavier, A., & Almeida, M. (2024). Transformative Social Innovation as a Guideline to Enhance the Sustainable Development Goals’ Framework. Sustainability, 16(16), 7114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167114