The Unintended Consequence of Environmental Regulations on Earnings Management: Evidence from Emissions Trading Scheme in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample Selection

3.2. Measurement for Earnings Management

3.3. Measurement for Control Variables

3.4. Sample Statistics

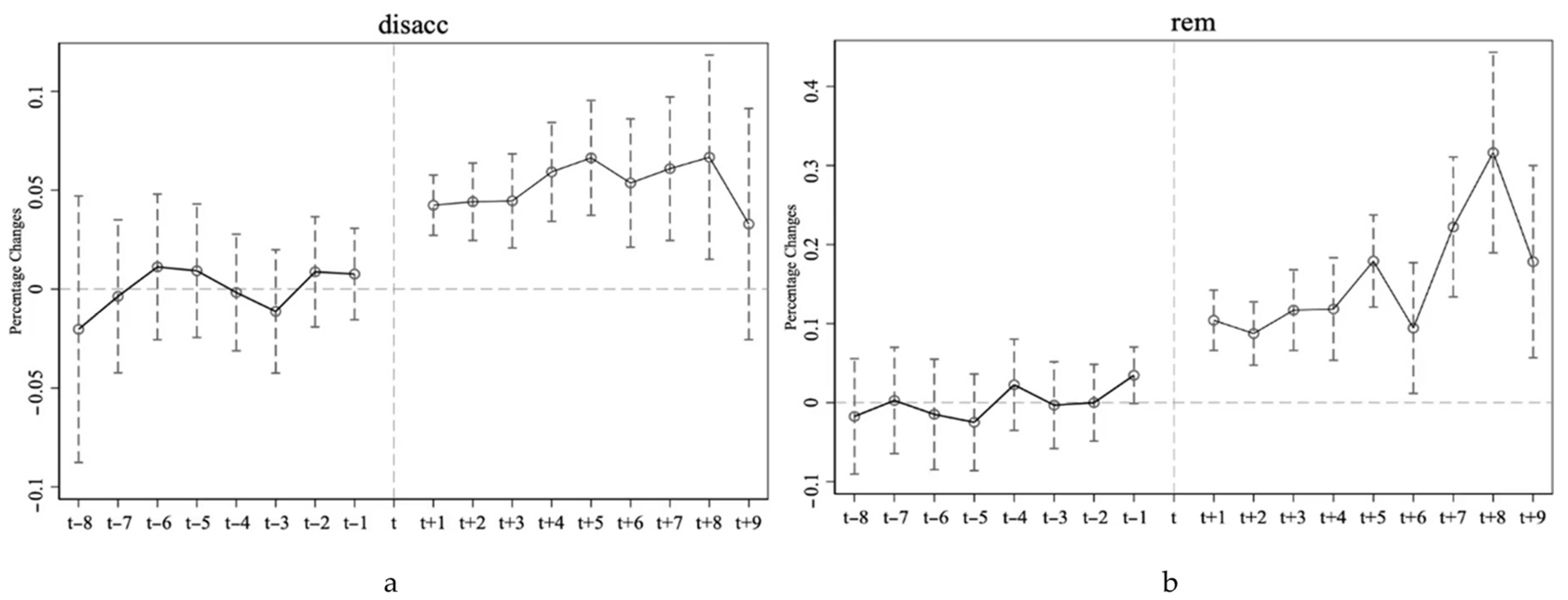

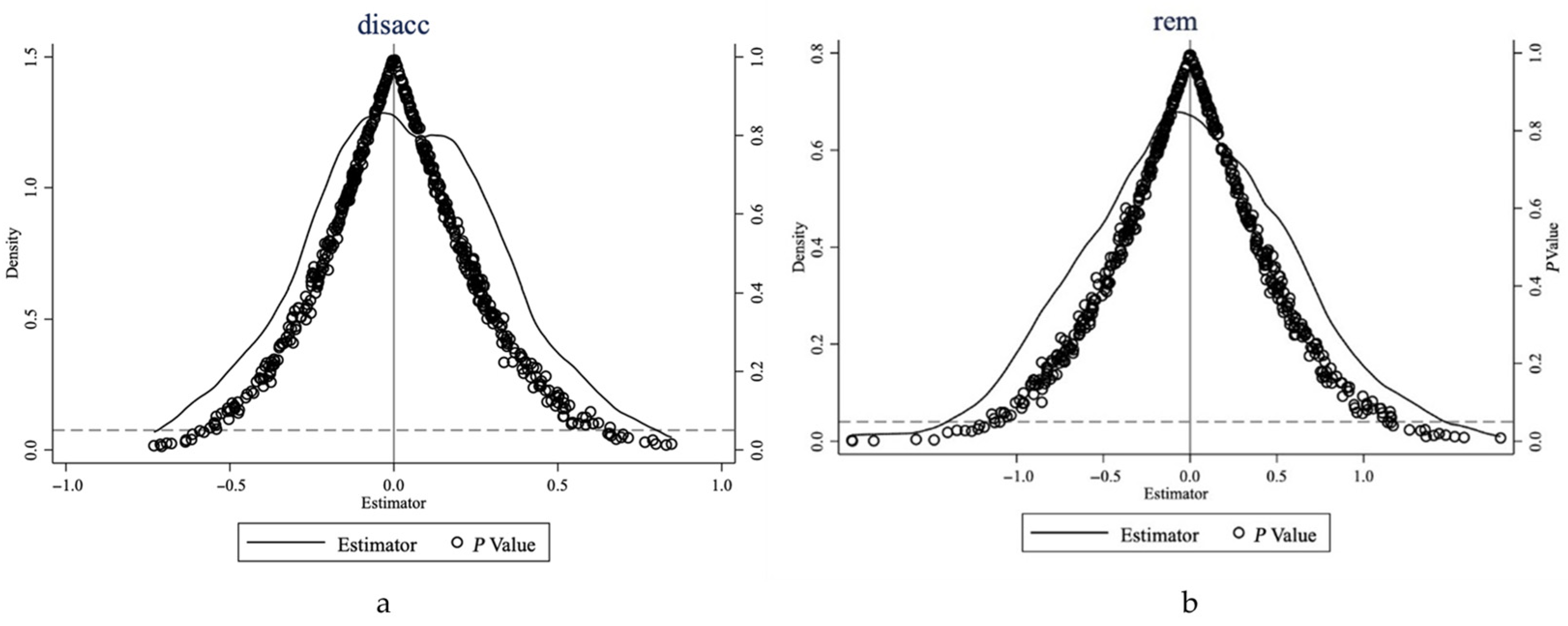

3.5. Difference-in-Difference

3.6. Model Specification

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Main Result

4.2. Mechanism Analysis

4.2.1. Mechanism—Financial Constraints

4.2.2. Mechanism—Firm Opacity

4.2.3. Mechanism—Market Competition

4.2.4. Mechanism—Emission Mitigation Pressure

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, X. Oil Price Uncertainty and Audit Fees: Evidence from the Energy Industry. Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Q.; Zhang, J.S. The Heterogeneous Impact of Different Types of Environmental Regulations on Local Environmental Governance. Commer. Res. 2020, 7, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, L.H.; Schein, A.R. Carbon Taxes Versus Cap and Trade: A Critical Review. Clim. Change Econ. 2013, 4, 1350010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, S.F.; Galdi, G.; Alloisio, I.; Borghesi, S. The EU ETS and Its Companion Policies: Any Insight for China’s ETS? Environ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 26, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.H.; Long, X.; Lu, J.; Morgenstern, R.D. China’s Unconventional Nationwide CO2 Emissions Trading System: Cost-Effectiveness and Distributional Impacts. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2022, 111, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, G.C.; Hilary, G.; Verdi, R.S. How Does Financial Reporting Quality Relate to Investment Efficiency? J. Account. Econ. 2009, 48, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, F.; Francis, J.; Kim, I.; Olsson, P.M.; Schipper, K. A Returns-Based Representation of Earnings Quality. Account. Rev. 2006, 81, 749–780. [Google Scholar]

- Cutillas Gomariz, M.F.; Sánchez Ballesta, J.P. Financial Reporting Quality, Debt Maturity and Investment Efficiency. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 40, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Wahlen, J.M. A Review of the Earnings Management Literature and Its Implications for Standard Setting. Account. Horiz. 1999, 13, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.L.; Zimmerman, J.L. Towards a Positive Theory of the Determination of Accounting Standards. Account. Rev. 1978, 53, 112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, R.M.; Smith, A.J. Financial Accounting Information and Corporate Governance. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 32, 237–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B.; Hasan, I.; Park, J.C.; Wu, Q. Gender Differences in Financial Reporting Decision Making: Evidence from Accounting Conservatism. Contemp. Account. Res. 2015, 32, 1285–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.P.; Liu, N.; Zhang, S.X. The Heterogeneous Environmental Regulation and the Earnings Information Quality. Account. Econ. Res. 2022, 36, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chen, S.; Jiao, Y.; Feng, X. How Does ESG Constrain Corporate Earnings Management? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Gupta, R.D. Environmental, Social and Governance Performance and Earnings Management—The Moderating Role of Law Code and Creditor’s Rights. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borralho, J.M.; Hernández-Linares, R.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Choban De Sousa Paiva, I. Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure’s Impacts on Earnings Management: Family versus Non-Family Firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.Q.; Wu, L.B.; Ren, F.Z. From “Spurring a Willing Horse” to Efficiency Driven: A Study of China’s Regional CO2 Emission Permit Allocation. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 54, 86–102. [Google Scholar]

- Calel, R.; Dechezlepretre, A. Environmental Policy and Directed Technological Change: Evidence from the European Carbon Market. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016, 98, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Cai, H.J.; Liu, M.J. Research on Enterprise Financial Effects of the Carbon Emission Trading—Based on the “Porter Hypothesis” & PSM-DID Test. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2020, 36, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.T.; Huang, N. Will the Carbon Emission Trading Scheme Improve Firm Value? Financ. Trade Econ. 2019, 40, 144–161. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Xiao, Y.Z. Have carbon emissions trading pilots promoted OFDI? ChinaPopul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Shen, J.; Miao, L.; Zhang, W. The Effects of Emission Trading Scheme on Industrial Output and Air Pollution Emissions under City Heterogeneity in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Can Carbon Emission Trading Scheme Achieve Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction? Evidence from the Industrial Sector in China. Energy Econ. 2020, 85, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.J.; Lopez, T.J. The Impact of National Influence on Accounting Estimates: Implications for International Accounting Standard-Setters. Int. J. Account. 2001, 36, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, S.M.; Hou, K.; Kim, S. Real Effects of Climate Policy: Financial Constraints and Spillovers. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 143, 668–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The Price of Sin The Effects of Social Norms on Markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M.; Trompeter, G. Corporate Responses to Political Costs: An Examination of the Relation between Environmental Disclosure and Earnings Management. J. Account. Public Policy 2003, 22, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, H. The Impact of the Revised Environmental Protection Law on Earnings Management of Heavy Polluting Enterprises-An Empirical Test Based on the Political Cost Hypothesis. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 13, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.G.; Liu, M.N. Have Smog Affected Earnings Management of Heavy-polluting Enterprises?—Based on the Political-Cost Hypothesis. Account. Res. 2015, 03, 26–33+94. [Google Scholar]

- Fudenberg, D.; Tirole, J. A Theory of Income and Dividend Smoothing Based on Incumbency Rents. J. Polit. Econ. 1995, 103, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M.L.; Park, C.W. Smoothing Income in Anticipation of Future Earnings. J. Account. Econ. 1997, 23, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.K.; Francis, J.R. Does Size Matter? The Influence of Large Clients on Office-Level Auditor Reporting Decisions. J. Account. Econ. 2000, 30, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew Hong, T.; Ivo, W.; Wong, T.J. Earnings Management and the Underperformance of Seasoned Equity Offerings. J. Financ. Econ. 1998, 50, 63–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; Zhang, L.Y. Study on the Effect of Earnings Management on Credit Financing. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 4, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.S.; Chen, C.; Du, M. Financing Demand, Enterprise Life Cycle and Earnings Management—Empirical Evidence Based on A-listed Non-financial Companies. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2016, 9, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, E.P.; Luu, B.V. International Variations in ESG Disclosure—Do Cross-Listed Companies Care More? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 75, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, L.R.; Milgrom, P.R. Bid, Ask and Transaction Prices in a Specialist Market with Heterogeneously Informed Traders. J. Financ. Econ. 1985, 14, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Lundholm, R. Cross-Sectional Determinants of Analyst Ratings of Corporate Disclosures. J. Account. Res. 1993, 31, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, M. Disclosure Policy, Information Asymmetry, and Liquidity in Equity Markets. Contemp. Account. Res. 1995, 11, 801–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerald, J.L.; Jian, Z. Disclosure Quality and Earnings Management. Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hunton, J.E.; Libby, R.; Mazza, C.L. Financial Reporting Transparency and Earnings Management. Account. Rev. 2006, 81, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Petroni, K.R.; Shen, M. Cherry Picking, Disclosure Quality, and Comprehensive Income Reporting Choices: The Case of Property-Liability Insurers*. Contemp. Account. Res. 2006, 23, 655–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.M.; Strömberg, D. Press Coverage and Political Accountability. J. Polit. Econ. 2010, 118, 355–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.G.; Cheng, C.; Hou, Q.S. Unemployment Governance, Labor Cost and Firm Earnings Management. J. Manag. Sci. 2016, 29, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Gao, H. Nonmonetary Benefits, Quality of Life, and Executive Compensation. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2013, 48, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhang, W.G.; Feng, Z.B. How Does Environmental Regulation Remove Resource Misallocation—An Analysis of the First Obligatory Pollution Control in China. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.M.; Sloan, R.G.; Sweeney, A.P. Causes and Consequences of Earnings Manipulation: An Analysis of Firms Subject to Enforcement Actions by the SEC. Contemp. Account. Res. 1996, 13, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P.; Skinner, D.J. Earnings Management: Reconciling the Views of Accounting Academics, Practitioners, and Regulators. Account. Horiz. 2000, 14, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Pittman, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.T. Stock Market Liberalization and Earnings Management: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. Contemp. Account. Res. 2023, 40, 2547–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-B.; Kim, J.W.; Lim, J.-H. Does XBRL Adoption Constrain Earnings Management_ Early Evidence from Mandated U.S. Filers. Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 2610–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Kothari, S.P.; Robin, A. The Effect of International Institutional Factors on Properties of Accounting Earnings. J. Account. Econ. 2000, 29, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Qu, X.; Yin, S. How Does Carbon Emissions Trading Policy Affect Accrued Earnings Management in Corporations? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.N.; Zingales, L. Do Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivities Provide Useful Measures of Financing Constraints? Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 169–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S. The Relationship between Firm Investment and Financial Status. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.W. Does Financial Development Reduce the Firm’s Financial Constraints. East China Econ. Manag. 2012, 47, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, M.A.; Khalil, R.; Khalil, M.K. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)—Augmented Investments in Innovation and Firms’ Value: A Fixed-Effects Panel Regression of Asian Economies. China Financ. Rev. Int. 2022, 14, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Su, T.; Meng, L. Corporate Earnings Management Strategy under Environmental Regulation: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 90, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, M.; Lagasio, V. Environmental, Social, and Governance and Company Profitability: Are Financial Intermediaries Different? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yan, Y.; Chen, C.; Luo, T.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H. Can Enterprise Green Transformation Inhibit Accrual Earnings Management? Evidence from China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H. Environmental Information Disclosure, Earnings Quality and the Readability and Emotional Tendencies of Management Discussion and Analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peress, J. Product Market Competition, Insider Trading, and Stock Market Efficiency. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, S.J. Competition and Corporate Performance. J. Polit. Econ. 1996, 104, 724–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.M.; Yang, X.Q.; Wei, H. Product Market Competition and Firm’s Stock Idiosyncratic Risk—Based on the Empirical Evidence of Chinese Listed Companies. Econ. Res. J. 2012, 47, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.Q.; Chen, H.W. Product Market Competition, Competitive Position and Audit Fees—Double considerations based on agency costs and business risks. Audit. Res. 2013, 3, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, P.; Kacperczyk, M. Do Investors Care about Carbon Risk? J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 517–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Discretional Accruals (DA) | refers to change in operating income, refers to change in account receivable and PPE t refers to net fixed asset. |

| Real Earnings Management (TREM) | |

| Size | Log(Total Assets) in year t−1 |

| Leverage | Total Debt/Total Asset in year t−1 |

| Free Cash flow | Operating Cash flow/Total Asset in year t−1 |

| Tangibility | Tangible Assets/Total Asset in year t−1 |

| Loss | A dummy variable equal to 1 when the firm has a negative net earnings in year t−1 |

| Growth | Sales growth in year t−1 |

| Duality | A dummy variable equal to 1 if the firm’s chairman and general manager are the same person |

| Independent Director | The number of independent directors/total directors in year t−1 |

| Board | Number of board members in year t−1 |

| Top1 | Shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder in year t−1 |

| Age | Year of listing in year t−1 |

| Panel A | (1) | ||||||

| Treat | |||||||

| Size | 0.335 *** | ||||||

| (0.035) | |||||||

| Lev | −0.469 ** | ||||||

| (0.220) | |||||||

| Free Cash Flow | 0.786 | ||||||

| (0.583) | |||||||

| Tangibility | 2.411 *** | ||||||

| (0.203) | |||||||

| Loss | 0.226 ** | ||||||

| (0.111) | |||||||

| Growth | −0.176 * | ||||||

| (0.105) | |||||||

| Duality | 0.294 *** | ||||||

| (0.079) | |||||||

| Independent Director | 1.710 ** | ||||||

| (0.697) | |||||||

| Board | 0.051 ** | ||||||

| (0.023) | |||||||

| Top1 | 0.831 *** | ||||||

| (0.230) | |||||||

| Age | 0.003 | ||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||

| _cons | −12.069 *** | ||||||

| (0.727) | |||||||

| N | 14,622 | ||||||

| R-Squared | 0.062 | ||||||

| Panel B | UnMatched | Mean | %reduct | t-test | |||

| Variable | Matched | Treated | Control | %bias | |bias| | t | p > |t| |

| Size | U | 22.784 | 22.158 | 50.3 | 15.44 | 0.000 | |

| M | 22.63 | 22.653 | −1.9 | 96.3 | −0.4 | 0.687 | |

| Lev | U | 0.44789 | 0.40711 | 20.8 | 6.2 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.43962 | 0.44092 | −0.7 | 96.8 | −0.14 | 0.887 | |

| Free Cash Flow | U | 0.06088 | 0.04849 | 19.6 | 5.71 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.05888 | 0.06021 | −2.1 | 89.3 | −0.45 | 0.650 | |

| Tangibility | U | 0.28483 | 0.20298 | 52.6 | 16.2 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.26771 | 0.26029 | 4.8 | 90.9 | 1.02 | 0.309 | |

| Loss | U | 0.1241 | 0.11219 | 3.7 | 1.13 | 0.259 | |

| M | 0.12346 | 0.12778 | −1.3 | 63.7 | −0.28 | 0.783 | |

| Growth | U | 0.13736 | 0.17027 | −9.8 | −2.69 | 0.007 | |

| M | 0.14342 | 0.12626 | 5.1 | 47.9 | 1.18 | 0.237 | |

| Duality | U | 0.28956 | 0.28722 | 0.5 | 0.16 | 0.877 | |

| M | 0.28507 | 0.31548 | −6.7 | −1202.4 | −1.4 | 0.162 | |

| Independent Director | U | 0.37972 | 0.37598 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 0.036 | |

| M | 0.37678 | 0.37851 | −3.1 | 53.8 | −0.65 | 0.515 | |

| Board | U | 8.7911 | 8.453 | 19.3 | 6.32 | 0.000 | |

| M | 8.6981 | 8.6665 | 1.8 | 90.7 | 0.38 | 0.703 | |

| Top1 | U | 0.37013 | 0.33222 | 25.8 | 7.91 | 0.000 | |

| M | 0.36689 | 0.36095 | 4 | 84.3 | 0.84 | 0.399 | |

| Age | U | 12.01 | 10.161 | 25.8 | 7.68 | 0.000 | |

| M | 11.557 | 11.691 | −1.9 | 92.7 | −0.39 | 0.696 | |

| Panel A | N | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

| Discretional Accruals | 10,226 | 0.073 | 0.068 | 0.001 | 0.054 | 0.395 |

| Real Earnings Management | 10,226 | −0.001 | 0.178 | −0.594 | 0.008 | 0.482 |

| Size | 10,226 | 22.203 | 1.106 | 20.057 | 22.075 | 26.064 |

| Leverage | 10,226 | 0.405 | 0.195 | 0.054 | 0.395 | 0.852 |

| Free Cash Flow | 10,226 | 0.052 | 0.064 | −0.139 | 0.05 | 0.238 |

| Tangibility | 10,226 | 0.204 | 0.133 | 0.002 | 0.187 | 0.68 |

| Loss | 10,226 | 0.117 | 0.321 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Growth | 10,226 | 0.153 | 0.343 | −0.519 | 0.106 | 2.187 |

| Duality | 10,226 | 0.312 | 0.463 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent Director | 10,226 | 0.376 | 0.053 | 0.333 | 0.364 | 0.571 |

| Board | 10,226 | 8.462 | 1.537 | 5 | 9 | 14 |

| Top1 | 10,226 | 0.336 | 0.141 | 0.088 | 0.317 | 0.729 |

| SOE | 10,226 | 0.318 | 0.466 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 10,226 | 10.197 | 7.172 | 1 | 8 | 30 |

| Panel B | Full sample | |||||

| Benchmark | Treat (CO2 ETS) | Total | ||||

| Year | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| 2012 | 51 | 5.72 | 364 | 3.9 | 415 | 4.06 |

| 2013 | 67 | 7.52 | 568 | 6.08 | 635 | 6.21 |

| 2014 | 71 | 7.97 | 646 | 6.92 | 717 | 7.01 |

| 2015 | 75 | 8.42 | 693 | 7.42 | 768 | 7.51 |

| 2016 | 70 | 7.86 | 721 | 7.72 | 791 | 7.74 |

| 2017 | 74 | 8.31 | 773 | 8.28 | 847 | 8.28 |

| 2018 | 75 | 8.42 | 854 | 9.15 | 929 | 9.08 |

| 2019 | 146 | 16.39 | 1565 | 16.76 | 1711 | 16.73 |

| 2020 | 152 | 17.06 | 1782 | 19.09 | 1934 | 18.91 |

| 2021 | 110 | 12.35 | 1369 | 14.67 | 1479 | 14.46 |

| N | 891 | 100 | 9335 | 100 | 10,226 | 100 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.024 *** | 0.080 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.015) | |

| Size | −0.013 *** | 0.020 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| Leverage | −0.001 | −0.065 *** |

| (0.011) | (0.025) | |

| Free Cash Flow | −0.006 | −0.191 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.037) | |

| Tangibility | 0.000 | −0.049 * |

| (0.014) | (0.029) | |

| Loss | 0.002 | −0.002 |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| Growth | 0.005 ** | −0.005 |

| (0.002) | (0.006) | |

| Duality | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| (0.003) | (0.006) | |

| Independent Director | −0.001 | −0.018 |

| (0.030) | (0.057) | |

| Board | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | |

| Top1 | 0.000 | 0.074 * |

| (0.016) | (0.040) | |

| Age | 0.002 *** | 0.005 *** |

| (0.001) | −(0.001) | |

| _cons | 0.335 *** | −0.420 ** |

| (0.078) | (0.171) | |

| Firm | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,226 | 10,226 |

| R-Squared | 0.030 | 0.044 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discretional Accruals | Discretional Accruals | Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | Real Earnings Management | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.021 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.097 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.016) | |

| KZ | 0.003 *** | −0.006 *** | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||||

| KZ × Treat × Post | 0.007 *** (0.002) | 0.019 *** (0.006) | ||||

| LFC | −0.000 | −0.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| LFC × Treat × Post | 0.110 * (0.065) | 0.219 * (0.119) | ||||

| SA | −0.002 | 0.080 | ||||

| (0.026) | (0.055) | |||||

| SA × Treat × Post | 0.049 ** (0.023) | 0.190 *** (0.051) | ||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 |

| R-Squared | 0.033 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.045 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discretional Accruals | Discretional Accruals | Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | Real Earnings Management | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.022 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.082 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| Transparency Rating | −0.002 | −0.004 | ||||

| (0.002) | (0.003) | |||||

| Transparency Rating × Treat × Post | −0.029 *** (0.005) | −0.044 *** (0.012) | ||||

| Analysts Attention | 0.003 *** | −0.007 *** | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.003) | |||||

| Analysts Attention × Treat × Post | −0.008 ** (0.004) | −0.015 * (0.009) | ||||

| Big4 | −0.005 | 0.005 | ||||

| (0.009) | (0.022) | |||||

| Big4 × Treat × Post | −0.028 * | −0.074 * | ||||

| (0.016) | (0.040) | |||||

| Contorls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 |

| R-squared | 0.035 | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.047 | 0.046 | 0.044 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discretional Accruals | Discretional Accruals | Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | Real Earnings Management | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.031 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.017 ** | 0.091 *** | 0.094 *** | 0.065 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.018) | |

| HHI | 0.006 | 0.023 | ||||

| (0.011) | (0.027) | |||||

| HHI × Treat × Post | 0.189 ** | 0.344 *** | ||||

| (0.076) | (0.130) | |||||

| Listed Firms | 0.003 | 0.006 | ||||

| (0.004) | (0.008) | |||||

| Listed Firms × Treat × Post | −0.014 * (0.008) | −0.033 ** (0.015) | ||||

| Lerner Index | 0.020 ** | 0.054 *** | ||||

| (0.008) | (0.019) | |||||

| Lerner Index × Treat × Post | 0.101 * (0.053) | 0.193 * (0.101) | ||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 | 10,226 |

| R-squared | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.033 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.049 |

| Panel A | CO2 Emissions at Firm Level | |||

| ≥Median | <Median | |||

| Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.025 *** | 0.088 *** | 0.006 | 0.032 |

| (0.009) | (0.023) | (0.006) | (0.022) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4968 | 4968 | 5258 | 5258 |

| R-Squared | 0.032 | 0.046 | 0.041 | 0.060 |

| Panel B | Level of Carbon Market Activity | |||

| High | Low | |||

| Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.018 * | 0.096 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.027 |

| (0.010) | (0.021) | (0.012) | (0.043) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2426 | 2426 | 1762 | 1762 |

| R-Squared | 0.044 | 0.077 | 0.065 | 0.106 |

| Panel C | Status of Carbon Peaking at Province Level | |||

| Peaked | On the way | |||

| Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | Discretional Accruals | Real Earnings Management | |

| Treat × Post | 0.013 | 0.045 | 0.023 *** | 0.090 *** |

| (0.016) | (0.045) | (0.006) | (0.016) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 875 | 875 | 9351 | 9351 |

| R-Squared | 0.075 | 0.172 | 0.032 | 0.040 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Tian, Y. The Unintended Consequence of Environmental Regulations on Earnings Management: Evidence from Emissions Trading Scheme in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167092

Chen W, Tian Y. The Unintended Consequence of Environmental Regulations on Earnings Management: Evidence from Emissions Trading Scheme in China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167092

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wei, and Yuan Tian. 2024. "The Unintended Consequence of Environmental Regulations on Earnings Management: Evidence from Emissions Trading Scheme in China" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167092

APA StyleChen, W., & Tian, Y. (2024). The Unintended Consequence of Environmental Regulations on Earnings Management: Evidence from Emissions Trading Scheme in China. Sustainability, 16(16), 7092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167092