(Re)shaping the Tourists’ Imagined Identity of Mosuo towards Sustainable Ethnic Tourism Development in Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Identity and Tourism

2.2. Sustainable Tourism Development

3. Sites and Research Methods

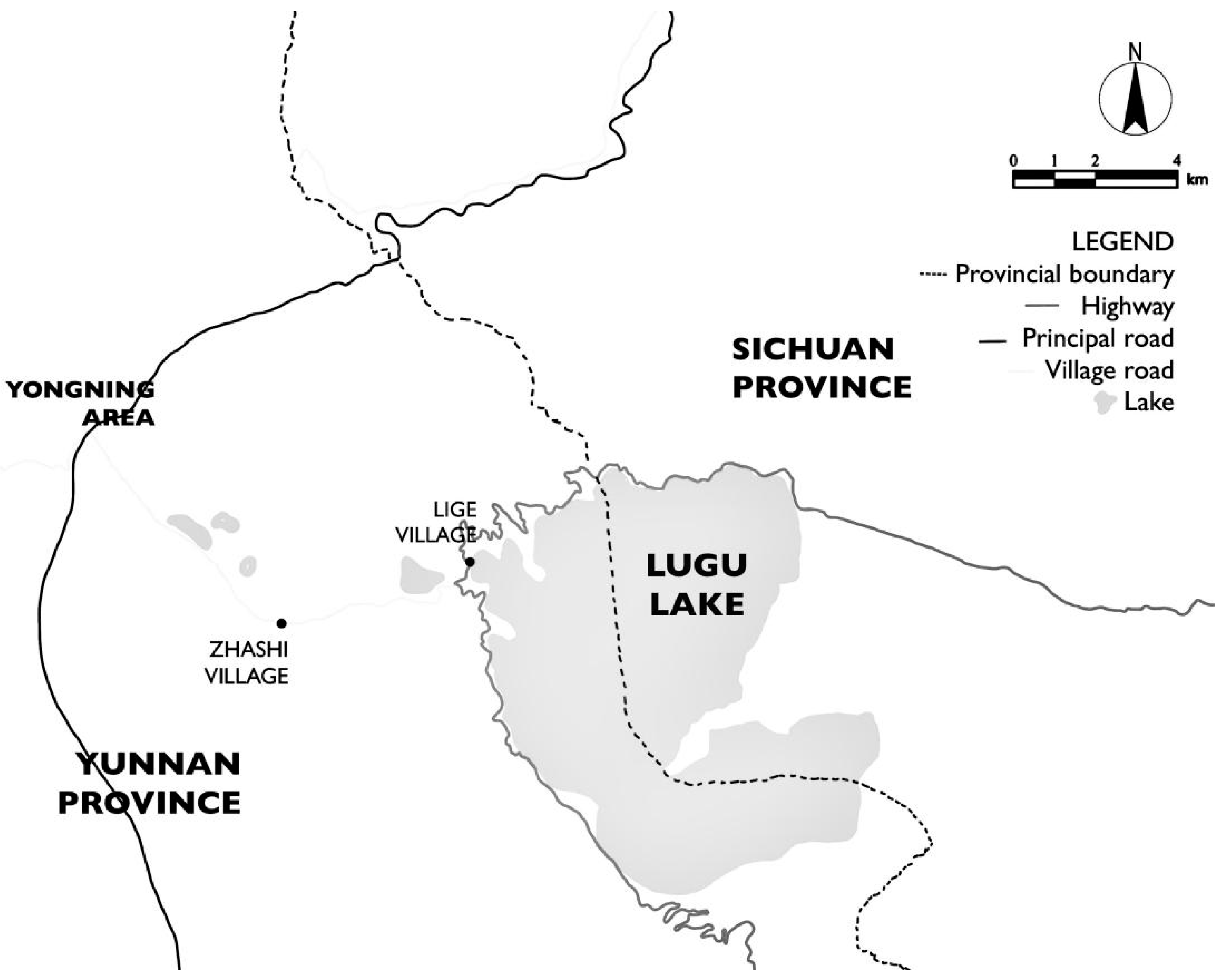

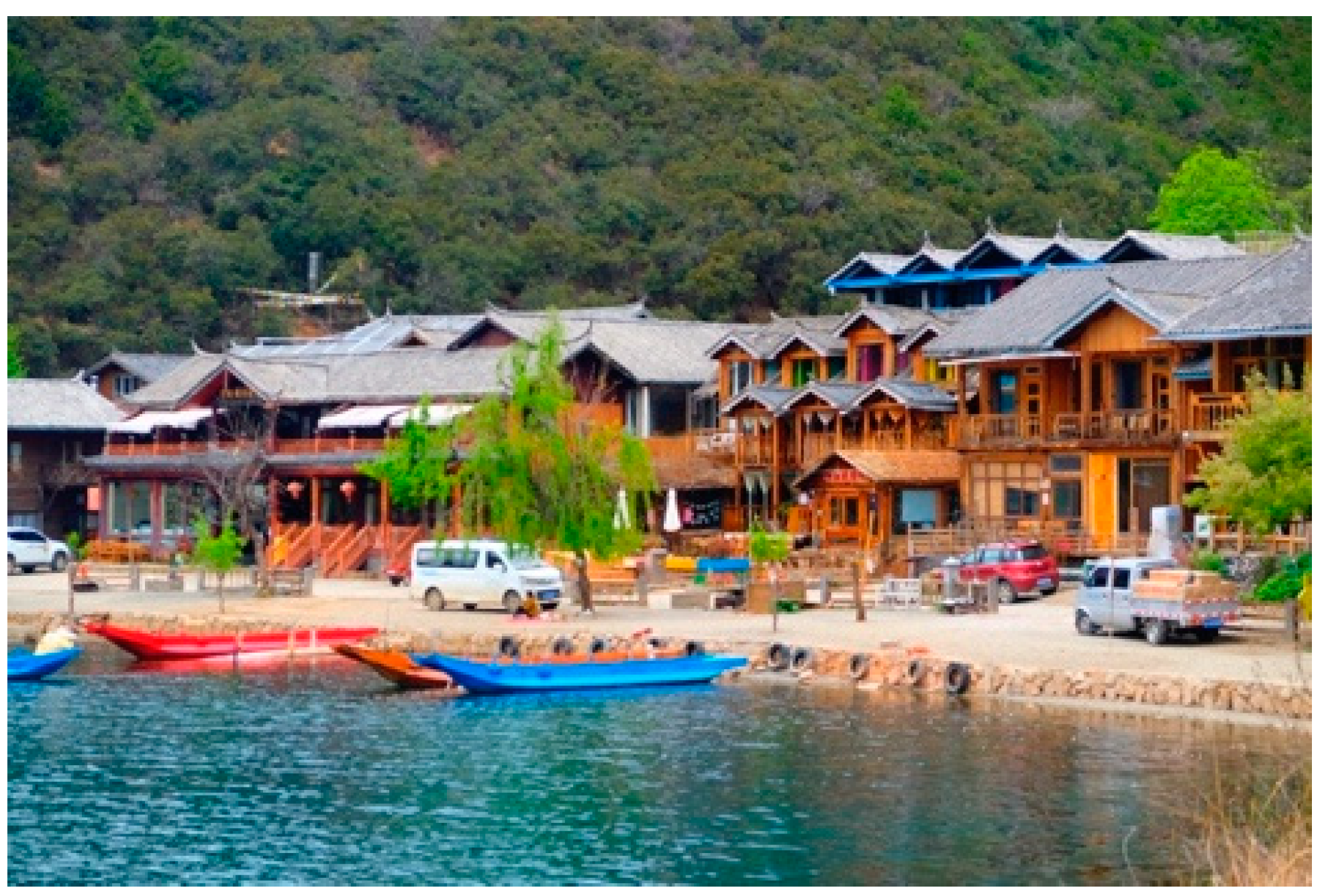

3.1. Sites: Zhashi and Lige Village

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

3.2.2. Questionnaire

3.2.3. Reflection

4. Results

4.1. Questionnaire Survey Results

4.1.1. Tourists’ Motivation and Expectation

4.1.2. Tourists’ Experience and Perception

4.1.3. Satisfaction of Mosuo Villages and Dwellings

4.2. Interview Survey Results

4.2.1. The Commodified Identity

4.2.2. The Renewed Identity

4.2.3. The Undefined Identity

5. Discussion

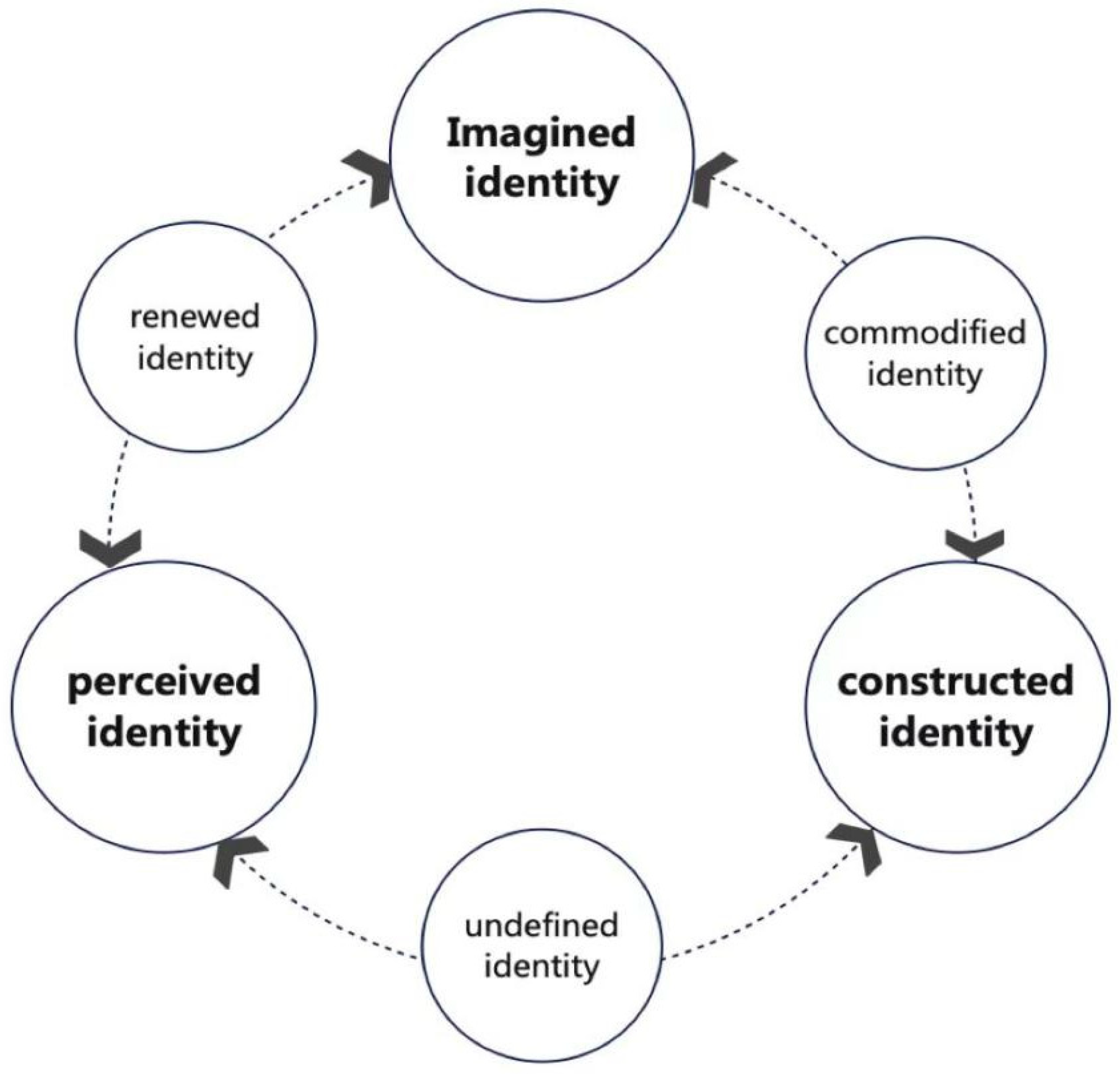

5.1. New Concept: Imagined Identity

5.2. Construction of Various Identities

5.3. The Lived and Renewed Identity—Towards the Sustainability of Ethnic Tourism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cornet, C. Tourism Development and Resistance in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.B.; Ayamba, E.C.; Udimal, T.B.; Agyemang, A.O.; Ruth, A. Tourism and Sustainable Development in China: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 39077–39093. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C. Cultural Diversity and Tourism Development in Yunnan Province, China. Geography 2005, 90, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. Song and Silence: Ethnic Revival on China’s Southwest Borders; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Morais, D.B.; Dowler, L. The Role of Community Involvement and Number/Type of Visitors on Tourism Impacts: A Controlled Comparison of Annapurna, Nepal and Northwest Yunnan, China. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Ethnic Tourism in Southeast Asia. In Tourism, Anthropology and China; Chee-Beng, T., Cheung, S.C.H., Hui, Y., Eds.; White Lotus Press: Bangkok, Thailand, 2001; pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G.; Smith, S. Ethnic Tourism Development: Chinese Government Perspectives. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Ethnic Tourism: A Framework and an Application. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Ethnic tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 318–320. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, X. How and Why Does Place Identity Affect Residents’ Spontaneous Culture Conservation in Ethnic Tourism Community? A Value Co-Creation Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1344–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administrative Council of the Lugu Lake Tourist Region. Development Report of Lugu Lake Tourism Industry; People’s Government of Lijiang City: Lijiang, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lugu Lake (Yunnan). Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/home/ztbd/2021/mlhhyxalzjhd/yxal/202201/t20220127_968337.shtml (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Mattison, S.M. Economic Impacts of Tourism and Erosion of the Visiting System among the Mosuo of Lugu Lake. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2010, 11, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Larkham, P. Building a New Heritage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel, S.H.; Maureira, T.M. Performing Identity and Culture in Indigenous Tourism—A Study of Indigenous Communities in Québec, Canada. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2017, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N. Cultural Sustainability, Tourism and Development: (Re)articulations in Tourism Contexts, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marine-Roig, E. The Image and Identity of the Catalan Coast as a Tourist Destination in Twentieth-century Tourist Guidebooks. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2011, 9, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C. Tourism Development and Changing Rural Identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Stokoe, E. Place and Identity in Tourists’ Accounts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Testing the Dimensionality of Place Attachment and Its Relationships with Place Satisfaction and Pro-Environmental Behaviours: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.M. Identity, Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.Y.; Wu, D.F.; Zhu, G.X.; Li, D.M. A Study on Identity in View of the Tourism Literatures. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 30, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.J.; Mireles, D.C. Identity Theory. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Ritzer, G., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P.J.; Stets, J.E. Identity Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sollberger, D. On Identity: From a Philosophical Point of View. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Xu, H. Tourists’ Construction of Diverse Identities with Natural Disaster Dark Heritage Sites. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 25, 1127–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, R. Cultural Heritage, Ethnic Tourism, and Minority-State Relations amongst the Orochen in North-East China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Ruan, W.Q.; Yang, T.T. National Identity Construction in Cultural and Creative Tourism: The Double Mediators of Implicit Cultural Memory and Explicit Cultural Learning. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211040789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barre, S.D. Wilderness and cultural tour guides, place identity and sustainable tourism in remote areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 825–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Jenkins, J. Destination Place Identity and Regional Tourism Policy. Tour. Geogr. 2003, 5, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Brown, G.; Lindsay, N.J. The Place Identity–Performance Relationship Among Tourism Entrepreneurs: A Structural Equation Modelling Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfant, M.; Allcock, J.B.; Bruner, E.M. (Eds.) International Tourism: Identity and Change; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M. Tourism and Place Identity: A Case-study in rural Ireland. Ir. Geogr. 1998, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, T.S. The Cultural Space of Modernity: Ethnic Tourism and Place Identity in China. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1993, 11, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C. Tourism and the Symbols of Identity. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Chen, J.S. The Influence of Place Identity on Perceived Tourism Impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, L. Commoditizing Culture: Tourism and Maya Identity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S. Which Heritage? Nature, Culture and Identity in French Rural Tourism. Fr. Hist. Stud. 2002, 25, 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G.; McGuirk, P.M. Making Time: Tourism and Heritage Representation at Millers Point, Sydney. Aust. Geogr. 1996, 27, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, D. Tourism and Ethnicity: The Brotherhood of Coconuts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 944–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclean, F. Introduction: Heritage and Identity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L.; Guglielmetti Mugion, R.; Renzi, M.F. Heritage And Identity: Technology, Values and Visitor Experiences. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; Macmillan: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. An Ethnography of Englishness: Experiencing Identity through Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.; Stevenson, D.; Young, T. Tourist Cultures: Identity, Place and the Traveller; SAGE Publications Ltd: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams, R. Tourism and the Reconfiguration of Host Group Identities: A Case Study of Ethnic Tourism in Rural Guangxi, China. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2015, 13, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, T.S. Ethnic Tourism in Guizhou: Sense of Place and the Commerce of Authenticity. In Tourism, Ethnicity, and the State in Asian and Pacific Societies; Picard, M., Wood, R.E., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stronza, A. Through a New Mirror: Reflections on Tourism and Identity in Amazon. Hum. Organ. 2008, 67, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelner, S. Tours That Bind: Diaspora, Pilgrimage, and Israeli Birthright Tourism; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Bernard, S.S. Heritage Tourism and Ethnic Identity: A Deductive Thematic Analysis of Jamaican Maroons. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2021, 7, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tantow, D. Globalization, Identity and Heritage Tourism—A Case Study of Singapore’s Kampong Glam. Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. Ethnic Tourism and Minority Identity: Lugu Lake, Yunnan, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 712–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasmann, R.F.; Milton, J.P.; Freeman, P.H. Ecological Principles for Economic Development; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, M. The World Conference on Sustainable Tourism. Dev. Pract. 1995, 5, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable Tourism: An Evolving Global Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in Sustainable Tourism Development and Their Roles: Applying Stakeholder Theory to Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. ourism, Sustainable Development and the Theoretical Divide: 20 Years On. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable Tourism Development and Competitiveness: The Systematic Literature Review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/8741/-Making%20Tourism%20More%20Sustainable_%20A%20Guide%20for%20Policy%20Makers-2005445.pdf?sequence=3&%3BisAllowed= (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Xie, P.F. Authenticating Ethnic Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2010; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. Tourists’ Perceptions of Ethnic Tourism in Lugu Lake, Yunnan, China. J. Herit. Tour. 2012, 7, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, I. Traditional Identity as a Potential in Sustainable Tourism Development. In Proceedings of the BITCO Thematic Tourism in a Global Environment: Advantages, Challenges and Future Developments, Belgrade, Serbia, 27–29 March 2014; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Compiling Committee of Ninglang Yi Autonomous County. Ninglang Yi Autonomous County Local Records (Ninglang Yizu Zizhixian Zhi); Yunnan Nationalities Publishing House: Kunming, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. The Main Data of the Seventh National Census. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/d7c/202303/P020230301403217959330.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Galletta, A.M. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.C. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; Wholey, J.S., Harty, H.P., Newcomer, K.E., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, B.L. Asking Questions: Techniques for Semistructured Interviews. PS Political Sci. Politics 2002, 35, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, D.M. Ethnography: Step-by-Step; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, G.R. Tourism Research, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Milton, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of Validity and Reliability in Qualitative Research. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, H.E.; Wallace, D.B. The Case Study Method and Evolving Systems Approach for Understanding Unique Creative People at Work. In Handbook of Creativity; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.K.; Drury, V.B. Legitimising the Subjectivity of Human Reality rough Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stokowski, P.A. Languages of Place and Discourses of Power: Constructing New Senses of Place. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Zhao, J.Z. The Native Mosuo People, Matriarchal Culture, and Development Processes in the Lugu Lake Region: Introduction. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C. Ethnic Tourism Advertisements: The Power Dynamic and Its Effect on Cultural Representation in the ‘Kingdom of Daughters’. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, E.R. From Nü Guo to Nü’er Guo: Negotiating Desire in The Land of The Mosuo. Mod. China 2005, 31, 448–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namu, Y.; Mathieu, M. Leaving Mother Lake: A Girlhood at the Edge of the World; Back Bay Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.J. Reconstructed Myth: An Ethnographic Study of Mosuo Cultural Heritage; The Ethnic Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.S. A Society without Fathers or Husbands? Discrimination against neither Female nor Male in the Mosuo Family; Guangming Daily Newspaper Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Awkward Visitors to the Mosuo Culture in Lugu Lake Often Ask for Walking Marriages. 2007. Available online: http://www.tourunion.com/info/htm/12621.htm (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Woychuk-Mlinac, L. Changes in Luoshui: How the Outside World Affects Luoshui Village and the Mosuo Culture. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2015, 2208. Available online: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2208 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Zhang, W. Tourism Development: Protection versus Exploitation—A Case Study of the Change in the Lives of the Mosuo People. J. GMS Dev. Stud. 2006, 3, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J. Tourism in Lugu Hu: Helpful or Harmful? Examining the Impact of Tourism on Lugu Lake’s People and Environment. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2007, 138. Available online: http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/138 (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Anderson, B. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism; Verso: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, T. Tourism and Modernity in China; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, N.B.; Graburn, N.H. (Eds.) Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches, 1st ed.; Berghahn Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, G. La Poétique de l’Espace; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, N. Locating Imaginaries in the Anthropology of Tourism. In Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches; Salazar, N., Graburn, N., Eds.; Berghahn Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 260–278. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, N.B. Tourism Imaginaries: A Conceptual Approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. Tourism and the Geographical Imagination. Leis. Stud. 1992, 11, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Ma, T. Tourism Situation: Between Imaginary and Place. J. Beijing Int. Stud. Univ. 2015, 37, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.Y. Construction of Tourist’s Place Imagination in the Context of Modernity. Master’s Thesis, Xi’ an International Studies University, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Till, K.E. Construction Sites and Showcases: Mapping the New Berlin through Tourism Practices. In Mapping Tourism; Hanna, S.P., Casino, V.J.D., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003; pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Berghe, P.V.; Keyes, C.F. Introduction Tourism and Re-created Ethnicity. Ann. Tour. Res. 1984, 11, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Cheung, S. The Perceived Destination Image of Hong Kong as Revealed in the Travel Blogs of Mainland Chinese Tourists. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2010, 11, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S. A Study on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity in Gala Village, Nyingchi Prefecture. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 18, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N.J. Culture, Identity and Tourism Representation: Marketing Cymru or Wales? Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.K. The Paradox Between Cultural Protection and Tourism Development: Reflections on ‘Construction and Protection of Mosuo Culture’. J. Southwest Front. Ethn. Stud. 2013, 1, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. Rural Revitalization in Ethnic Regions about the Research of “Mosuo Home” Pattern—In the Case of Cultural Ecology Protection and Integration Development of Urban and Rural Areas as the Center. J. Qinghai Natl. Univ. 2019, 45, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.L.; Yu, L.; Lu, Q. A Study on British Rural Buildings and Settlement Conservation as Exemplified in the Case of Cotswolds. Archit. J. 2018, 7, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, N.H.; Peng, Z.R.; Zhao, H.M. Anthropological Comments on Sustainable Development of Tourism in China. Tour. Trib. 2006, 1, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, N.H. Anthropology and the Age of Tourism; Guangxi Normal University Press: Guilin, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.C. Cultural Architectural Assets: A New Framework to Study Changes and Continuity of Dwellings of Mosuo Tribe in Transitions. Ph.D. Thesis, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.C.; Xiao, J.L. Dynamic Authenticity: Understanding and Conserving Mosuo Dwellings in China in Transitions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tourist motivation and expectation | ||

| Mosuo matriarchal culture | 5 | 5.21 |

| Natural scenery | 9 | 9.38 |

| Mosuo matriarchal culture and natural scenery | 54 | 56.3 |

| Rest and relaxation | 23 | 24.0 |

| Other reasons | 4 | 4.17 |

| Not known | 1 | 1.04 |

| Categories | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tourist destination | ||

| Lige village | 29 | 30.2 |

| Daluoshui village | 25 | 26.0 |

| Zhudi village | 37 | 38.5 |

| Sanjia village | 2 | 2.08 |

| Not known | 3 | 3.13 |

| Stay for days | ||

| 2 | 76 | 79.2 |

| 3 | 15 | 15.6 |

| More than 3 days | 4 | 4.17 |

| Not known | 1 | 1.04 |

| Tourist activities | ||

| Cultural activities | 36 | 37.5 |

| Natural outdoor activities | 58 | 60.4 |

| Not known | 2 | 2.08 |

| Categories | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The most representative Mosuo villages | ||

| Zhashi village | 28 | 29.2 |

| Zhudi village | 11 | 11.6 |

| Lige village | 13 | 13.5 |

| Lijiazui village (Sichuan Province) | 2 | 2.08 |

| Yanyuan county (Sichuan Province) | 5 | 5.21 |

| Huxin island | 2 | 2.08 |

| All can represent | 9 | 9.38 |

| None | 6 | 6.25 |

| Not known | 18 | 18.8 |

| The ‘most impression’ part of Mosuo villages and dwellings | ||

| Courtyard house | 9 | 9.38 |

| The Grandmother’s house | 19 | 19.8 |

| Muleng house | 34 | 35.4 |

| The Flower house | 1 | 1.04 |

| Dedicated wood carving | 2 | 2.08 |

| Lake-view guesthouses | 3 | 3.13 |

| No impression | 25 | 26.0 |

| Not known | 3 | 3.13 |

| Categories | Satisfied (%) | Neutral (%) | Dissatisfied (%) | N/K (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Mosuo villages and dwellings | 34.4 | 18.6 | 40.6 | 6.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, H.; Xiao, J. (Re)shaping the Tourists’ Imagined Identity of Mosuo towards Sustainable Ethnic Tourism Development in Southwest China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167042

Feng H, Xiao J. (Re)shaping the Tourists’ Imagined Identity of Mosuo towards Sustainable Ethnic Tourism Development in Southwest China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167042

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Huichao, and Jieling Xiao. 2024. "(Re)shaping the Tourists’ Imagined Identity of Mosuo towards Sustainable Ethnic Tourism Development in Southwest China" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167042

APA StyleFeng, H., & Xiao, J. (2024). (Re)shaping the Tourists’ Imagined Identity of Mosuo towards Sustainable Ethnic Tourism Development in Southwest China. Sustainability, 16(16), 7042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167042