Mapping Circular Economy in Portuguese SMEs

Abstract

1. Introduction

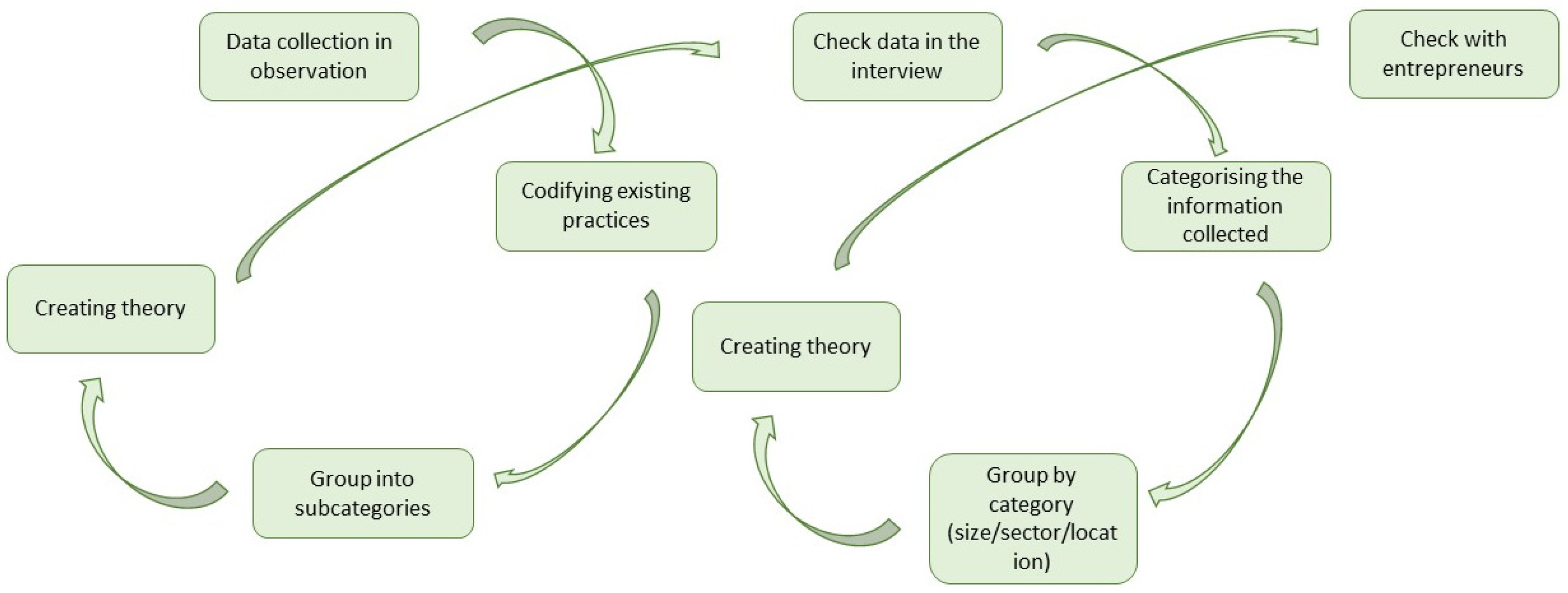

2. Research Methodology

3. Preparing the Interviews

3.1. Refining the Process

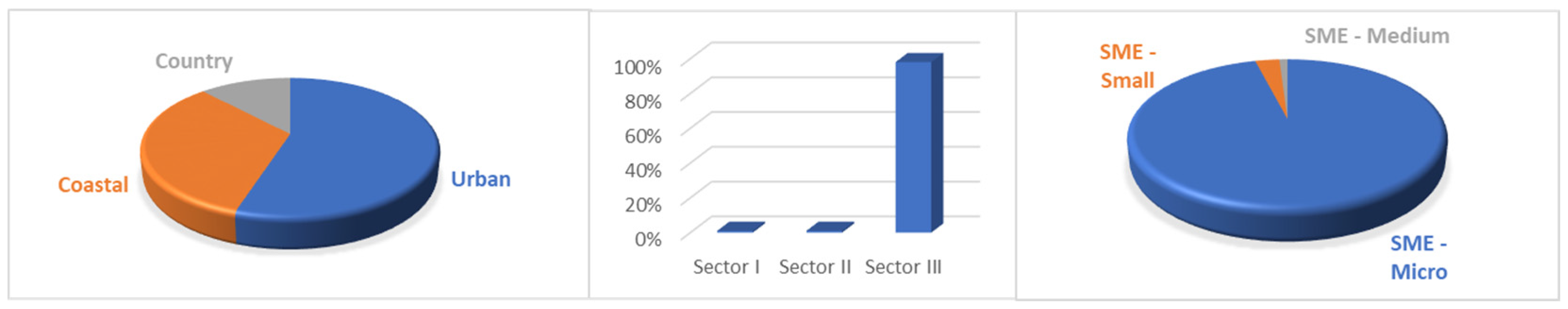

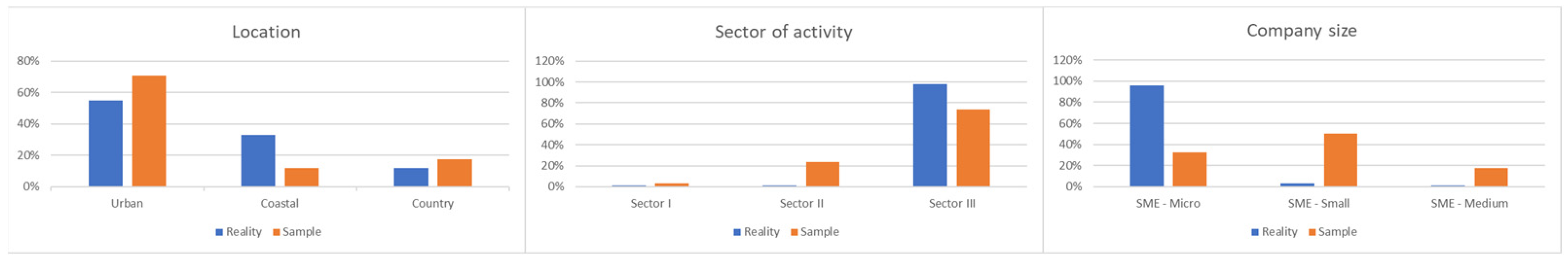

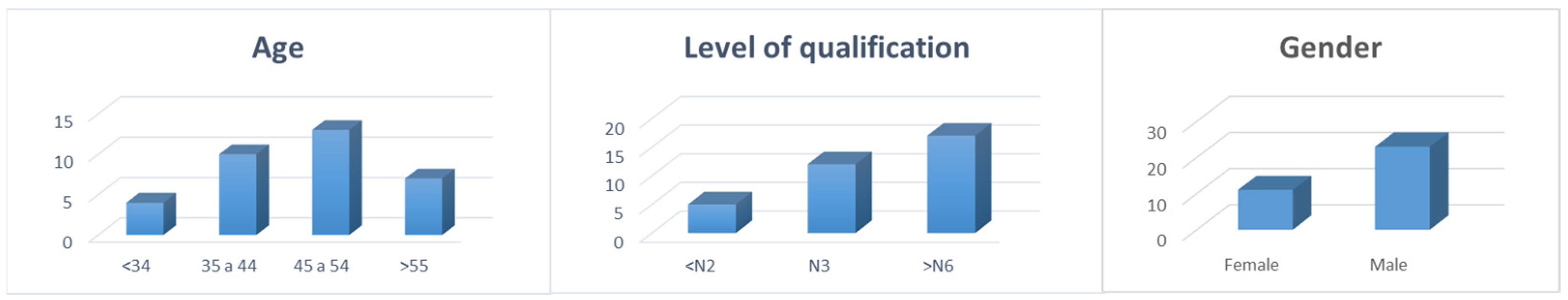

3.2. Sample Constitution and Characterization

4. Interview Results

4.1. Quantitative Analysis

4.2. Qualitative Analysis of the Results

- SME customers

- P 1.1—Customers might not value products and services that offer circularity

- P 1.2—Customers could penalize companies that are careless with CE issues

- P 1.3—Communication and marketing of CE Practices adopted is not efficient

- P 1.4—Measurement of the impact of CE practices is not effective

- SME employees

- P 2—The majority of workers might not value the CE practices implemented in the companies where they work

- SME top managers

- P 3.1—Legislation on CE could be inefficient

- P 3.2—There might be an imbalance between costs and benefits

- P 3.3—It could be difficult to quantify the impact of CE practices

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Companies Interviewed

| Data | Age | Level of Qualification | Gender | No. of Employees | EAC Rev 3 Main | Technical and R&D Staff | Turnover | Dimension | Headquarters Location | Foundation Year | Certifications |

| E1 | 34 | N3 | M | 27 | 08112 | 2 | 1,033,536.74 € | SME—Small | Country | 1987 | None |

| E2 | 52 | N6 | F | 14 | 31091 | 0 | 418,227.00 € | SME—Small | Urban | 2008 | None |

| E3 | 48 | N6 | M | 4 | 47711 | 0 | 195,735.05 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 1964 | None |

| E4 | 23 | N7 | F | 5 | 68200 | 1 | 732,726.45 € | SME—Medium | Urban | 2015 | None |

| E5 | 44 | N3 | M | 15 | 81300 | 1 | 316,770.96 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 2013 | None |

| E6 | 62 | N3 | M | 37 | 46341 | 0 | 7,809,009.71 € | SME—Small | Urban | 1993 | None |

| E7 | 36 | N7 | M | 17 | 91030 | 2 | 415,955.49 € | SME—Small | Urban | 2011 | None |

| E8 | 44 | N4 | F | 16 | 46732 | 0 | 2,017,035.20 € | SME—Small | Coastal | 1985 | ISO 9001 |

| E9 | 41 | N7 | M | 17 | 68322 | 1 | 382,997.77 € | SME—Medium | Urban | 2004 | None |

| E10 | 31 | N6 | F | 61 | 43210 | 2 | 1,395,609.96 € | SME—Medium | Urban | 2006 | None |

| E11 | 57 | N6 | M | 48 | 86220 | 2 | 2,386,940.12 € | SME—Medium | Urban | 1998 | DGERT; ERS |

| E12 | 32 | N3 | F | 7 | 93293 | 0 | 266,019.70 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 2016 | None |

| E13 | 51 | N3 | M | 12 | 47300 | 0 | 2,617,424.69 € | SME—Small | Urban | 1999 | None |

| E14 | 55 | N6 | M | 15 | 46421 | 0 | 2,215,956.73 € | SME—Small | Country | 2005 | ISO 9001 |

| E15 | 50 | N6 | M | 11 | 71120 | 1 | 374,700.04 € | SME—Small | Urban | 1994 | ISO 9001 |

| E16 | 44 | N3 | M | 3 | 45200 | 0 | 206,518.92 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 1989 | None |

| E17 | 47 | N3 | M | 4 | 45200 | 0 | 238,291.06 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 1987 | None |

| E18 | 39 | N1 | M | 5 | 25120 | 0 | 461,362.51 € | SME—Micro | Country | 1980 | None |

| E19 | 60 | N2 | M | 25 | 47112 | 0 | 4,282,819.87 € | SME—Small | Country | 1994 | None |

| E20 | 45 | N2 | M | 8 | 56101 | 0 | 371,746.53 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 2000 | None |

| E21 | 43 | N6 | M | 93 | 31091 | 6 | 13,292,221.08 € | SME—Medium | Urban | 2004 | ISO 9001; ISO 14000 |

| E22 | 46 | N3 | M | 14 | 47410 | 1 | 888,407.03 € | SME—Medium | Urban | 1995 | ISO 9001 |

| E23 | 68 | N2 | M | 6 | 31091 | 1 | 502,570.72 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 1989 | None |

| E24 | 34 | N6 | F | 11 | 81100 | 0 | 176,240.73 € | SME—Small | Urban | 2013 | None |

| E25 | 45 | N6 | F | 46 | 46610 | 2 | 6,078,560.11 € | SME—Small | Country | 1998 | ISO 9001 |

| E26 | 50 | N6 | F | 19 | 47591 | 1 | 1,573,238.17 € | SME—Small | Urban | 1998 | None |

| E27 | 42 | N6 | M | 7 | 62020 | 3 | 361,434.47 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 2016 | None |

| E28 | 46 | N6 | M | 9 | 62020 | 2 | 469,864.81 € | SME—Micro | Urban | 2008 | None |

| E29 | 47 | N7 | F | 18 | 85591 | 2 | 1,157,343.00 € | SME—Small | Urban | 1990 | DGERT |

| E30 | 45 | N6 | F | 10 | 85591 | 2 | 1,797,810.00 € | SME—Small | Urban | 2000 | DGERT |

| E31 | 58 | N3 | F | 3 | 96010 | 0 | 55,887.76 € | SME—Micro | Country | 2003 | None |

| E32 | 44 | N6 | M | 38 | 16293 | 2 | 2,794,753.42 € | SME—Small | Coastal | 1982 | ISO 9001; ISO 14000 |

| E33 | 53 | N3 | M | 14 | 23120 | 1 | 1,041,760.06 € | SME—Small | Coastal | 1994 | ISO 9001 |

| E34 | 55 | N2 | M | 16 | 18120 | 1 | 921,615.02 € | SME—Small | Urban | 2012 | ISO 9001; FSC |

Appendix B. Spearman Correlations

| GI | AI | IQL | EA | HL | YCF | CS | STD | EC | ICEP | DICE | VCE | |||

| Spearman’s rho | GI | Correlation Coefficient | 1000 | 0.212 | −0.250 | −0.242 | 0.089 | 0.112 | −0.158 | 0.007 | 0.030 | 0.011 | −0.061 | −0.116 |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.228 | 0.154 | 0.167 | 0.618 | 0.527 | 0.373 | 0.969 | 0.864 | 0.951 | 0.732 | 0.514 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| AI | Correlation Coefficient | 0.212 | 1000 | −0.295 | 0.195 | 0.128 | 0.120 | −0.103 | −0.157 | 0.186 | −0.135 | 0.004 | −0.065 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.228 | 0.091 | 0.270 | 0.469 | 0.499 | 0.564 | 0.376 | 0.292 | 0.445 | 0.983 | 0.713 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| IQL | Correlation Coefficient | −0.250 | −0.295 | 1000 | 0.283 | −0.378 * | −0.138 | 0.401 * | 0.555 ** | 0.201 | −0.078 | 0.415 * | 0.085 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.154 | 0.091 | 0.105 | 0.027 | 0.435 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.255 | 0.662 | 0.015 | 0.633 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| EA | Correlation Coefficient | −0.242 | 0.195 | 0.283 | 1000 | −0.052 | 0.038 | 0.092 | −0.157 | −0.035 | −0.286 | 0.153 | 0.090 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.167 | 0.270 | 0.105 | 0.770 | 0.832 | 0.604 | 0.376 | 0.843 | 0.101 | 0.388 | 0.614 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| HL | Correlation Coefficient | 0.089 | 0.128 | −0.378 * | −0.052 | 1000 | 0.060 | −0.025 | −0.249 | 0.235 | 0.142 | −0.141 | −0.115 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.618 | 0.469 | 0.027 | 0.770 | 0.737 | 0.887 | 0.156 | 0.181 | 0.423 | 0.427 | 0.518 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| YCF | Correlation Coefficient | 0.112 | 0.120 | −0.138 | 0.038 | 0.060 | 1000 | −0.147 | −0.151 | 0.101 | −0.373 * | −0.285 | −0.063 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.527 | 0.499 | 0.435 | 0.832 | 0.737 | 0.407 | 0.395 | 0.570 | 0.030 | 0.102 | 0.723 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| CS | Correlation Coefficient | −0.158 | −0.103 | 0.401 * | 0.092 | −0.025 | −0.147 | 1000 | 0.379 * | 0.428 * | −0.044 | 0.510 ** | −0.134 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.373 | 0.564 | 0.019 | 0.604 | 0.887 | 0.407 | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.806 | 0.002 | 0.448 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| STD | Correlation Coefficient | 0.007 | −0.157 | 0.555 ** | −0.157 | −0.249 | −0.151 | 0.379 * | 1000 | 0.313 | −0.031 | 0.381 * | −0.063 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.969 | 0.376 | 0.001 | 0.376 | 0.156 | 0.395 | 0.027 | 0.071 | 0.861 | 0.026 | 0.722 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| EC | Correlation Coefficient | 0.030 | 0.186 | 0.201 | −0.035 | 0.235 | 0.101 | 0.428 * | 0.313 | 1000 | −0.014 | 0.377 * | −0.426 * | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.864 | 0.292 | 0.255 | 0.843 | 0.181 | 0.570 | 0.012 | 0.071 | 0.939 | 0.028 | 0.012 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| ICEP | Correlation Coefficient | 0.011 | −0.135 | −0.078 | −0.286 | 0.142 | −0.373 * | −0.044 | −0.031 | −0.014 | 1000 | −0.244 | 0.103 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.951 | 0.445 | 0.662 | 0.101 | 0.423 | 0.030 | 0.806 | 0.861 | 0.939 | 0.165 | 0.561 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| DICE | Correlation Coefficient | −0.061 | 0.004 | 0.415 * | 0.153 | −0.141 | −0.285 | 0.510 ** | 0.381 * | 0.377 * | −0.244 | 1000 | −0.192 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.732 | 0.983 | 0.015 | 0.388 | 0.427 | 0.102 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.028 | 0.165 | 0.277 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| VCE | Correlation Coefficient | −0.116 | −0.065 | 0.085 | 0.090 | −0.115 | −0.063 | −0.134 | −0.063 | −0.426 * | 0.103 | −0.192 | 1000 | |

| Sig, (2-tailed) | 0.514 | 0.713 | 0.633 | 0.614 | 0.518 | 0.723 | 0.448 | 0.722 | 0.012 | 0.561 | 0.277 | |||

| N | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | 34,000 | ||

| *, Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed), **, Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), GI—Gender of the interviewed; AI—Age of the interviewed; IQL—Interviewed’s qualification level; EA—Economic activity; HL—Headquarters location; YCF—Year of company foundation; CS—Company size; STD—Size of the technical department; EC—Existing certifications; ICEP—Implemented CE practices; DICE—Disclosure of implemented CE practices; VCE—Valuation of CE practices by the client. | ||||||||||||||

Appendix C. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

References

- Medaglia, R.; Rukanova, B.; Zhang, Z. Digital government and the circular economy transition: An analytical framework and a research agenda. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramveliotakis, G.; Manioudis, M. History, knowledge, and sustainable economic development: The contribution of john stuart mill’s grand stage theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circular Material Use Rate. Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20231114-2 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Lima, F. Empresas em Portugal–2020. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kannazarova, Z.; Juliev, M.; Muratov, A.; Abuduwaili, J. Groundwater in the commonwealth of independent states: A bibliometric analysis of scopus-based papers from 1972 to 2023, emphasizing the significance of drainage. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Raposo, D.; Neves, J.; Silva, F.; Ribeiro, R.; Fernandes, M.E. Gamification in Communicating the Concept of Circular Economy—A Design Approach. In Advances in Ergonomics in Design; Rebelo, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J.C.; Lopes, J.M.; Farinha, L.; Silva, S.; Luízio, M. Orchestrating entrepreneurial ecosystems in circular economy: The new paradigm of sustainable competitiveness. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Subramanian, N.; Dora, M. Circular economy and digital capabilities of SMEs for providing value to customers: Combined resource-based view and ambidexterity perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, F.; Guidolin, M. Resource efficiency and circular economy in european smes: Investigating the role of green jobs and skills. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, F.; Dias, J.G. The use of circular economy practices in SMEs across the EU. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van Der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despoudi, S.; Sivarajah, U.; Spanaki, K.; Charles, V.; Durai, V.K. Industry 4.0 and circular economy for emerging markets: Evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Indian food sector. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, R. Waste Management in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): Compliance with Duty of Care and implications for the Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Barton, A.; O’Loughlin, A.; Kandra, H.S. Exploratory Survey of Australian SMEs: An Investigation into the Barriers and Opportunities Associated with Circular Economy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 3, 1275–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R.; Dowell, D.; Morris, W. Hospitality SMEs and the circular economy: Strategies and practice post—COVID. Br. Food J. 2023, 126, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Prada, P.; Lenihan, H.; Doran, J.; Rammer, C.; Perez-Alaniz, M. Driving the circular economy through public environmental and energy R&D: Evidence from SMEs in the European Union. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 182, 106884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, S.; Desjeux, D.; Moussaoui, I. Les méthodes Qualitatives. Presses Universitaires de France, «Que sais-je?». 2019. ISBN 9782130817154. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/les-methodes-qualitatives--9782130817154.htm (accessed on 10 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Investigaçao Qualitativa em Educaçao-Uma Introdução à Teoria e Aos Métodos; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 1994; ISBN 972-0-34112-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4129-2346-0. [Google Scholar]

- Maitiniyazi, S.; Canavari, M. Understanding Chinese consumers’ safety perceptions of dairy products: A qualitative study. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1837–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivinos, A. Introdução à Pesquisa Em Ciências Sociais: A Pesquisa Qualitativa em Educação; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas, A.R. ANÁLISE DE CONTEÚDO: UM CASO DE APLICAÇÃO AO ESTUDO DOS VALORES E REPRESENTAÇÕES SOCIAIS. In Metodologias de Investigação Sociológica-Problemas e Soluções a Partir de Estudos Empíricos; Edições Humus: Lisbona, Portugal, 2016; pp. 261–286. ISBN 978-989-755-223-6. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E.J. Entrevista Semiestruturada: Análise de objetivos e de roteiros. Semin. Int. Sobre Pesqui. Estud. Qual. 2004, 2, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, J.R.; Santos, S.C.M.D. Análise de conteúdo em pesquisa qualitativa. Rev. Pesqui. Debate Educ. 2020, 10, 1396–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowen, A.M.D. Pleasure a creative Approach to Life; The Alexander Lowen Foundation. 2013. ISBN 9781938485114. Available online: http://www.summus.com.br (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Kenessey, Z. The primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary sectors of the economy. Rev. Income Wealth 1987, 33, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guia do Utilizador Relativo à Definição de PME. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/756d9260-ee54-11ea-991b-01aa75ed71a1/language-pt (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Pequenas e Médias Empresas: Total e Por Dimensão. PORDATA. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/pt (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccascia, L. The impact of technical and economic disruptions in industrial symbiosis relationships: An enterprise input-output approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 213, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, S.; Ramos, T.R.P.; Leitão, M.M.R.; Barbosa-Povoa, A.P. Effectiveness of extended producer responsibility policies implementation: The case of Portuguese and Spanish packaging waste systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Haugrønning, V.; Throne-Holst, H.; Strandbakken, P. Increasing repair of household appliances, mobile phones and clothing: Experiences from consumers and the repair industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 125349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NoParast, M.; Hematian, M.; Ashrafian, A.; Amiri, M.J.T.; AzariJafari, H. Development of a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm for implementing circular economy strategies in the concrete industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankammer, S.; Brenk, S.; Fabry, H.; Nordemann, A.; Piller, F.T. Towards circular business models: Identifying consumer needs based on the jobs-to-be-done theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švecová, L.; Ostapenko, G.; Veber, J.; Valeeva, Y. The implementation challenges of zero carbon and zero waste approaches. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Kazan, Russia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, R.J.; Ferreira, J.V.; Ramos, A.L. The Consumer’s Role in the Transition to the Circular Economy: A State of the Art Based on a SLR with Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramveliotakis, G.; Manioudis, M. Sustainable development, COVID-19 and small business in Greecep: Small is not beautiful. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE practices mentioned by interviewees | Utilisation of waste such as MP—macdame, crusher | Extend service life—better build quality, used repair | Repairing items | Shared mobility with other companies |

| Industrial integration (manufacturing) | Utilising waste as PM—stuffing cushions | Reduced energy consumption—led lighting | Reducing paper use | |

| Reduced energy consumption—led lighting | Reduced energy consumption—led lighting | Reducing energy consumption—Shop window lighting | Digitisation for remote assistance | |

| Sorting rubbish for recycling | Sorting rubbish for recycling | Sorting rubbish for recycling | Sorting rubbish for recycling | |

| Reduced energy consumption—AC rules | ||||

| Marketing | ||||

| CE practices detected during the visit to the test companies | Waste reduction—diamond wire cutting | Industrial integration (production)—exchange of waste with other companies | Laundry—collection point | Extended product life with guarantees and maintenance |

| Current inverters—reducing consumption | Sustainable products and packaging—recover delivery packaging | Sale of batches of discontinued products | Shared product—through (REC) Renewable Energy Community | |

| Reducing emissions—quarry rights plans | Product remanufacturing—sofa restoration | Product as a service—Renting uniforms | Reduced consumption—panels increase from 350 W to 550 W | |

| Product as a service—equipment hire |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carreira, R.J.; Ferreira, J.V.; Ramos, A.L. Mapping Circular Economy in Portuguese SMEs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167009

Carreira RJ, Ferreira JV, Ramos AL. Mapping Circular Economy in Portuguese SMEs. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167009

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarreira, Rui Jorge, José Vasconcelos Ferreira, and Ana Luísa Ramos. 2024. "Mapping Circular Economy in Portuguese SMEs" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167009

APA StyleCarreira, R. J., Ferreira, J. V., & Ramos, A. L. (2024). Mapping Circular Economy in Portuguese SMEs. Sustainability, 16(16), 7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167009