Exploring Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Healthy-Labeled Foods at a Premium Price

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

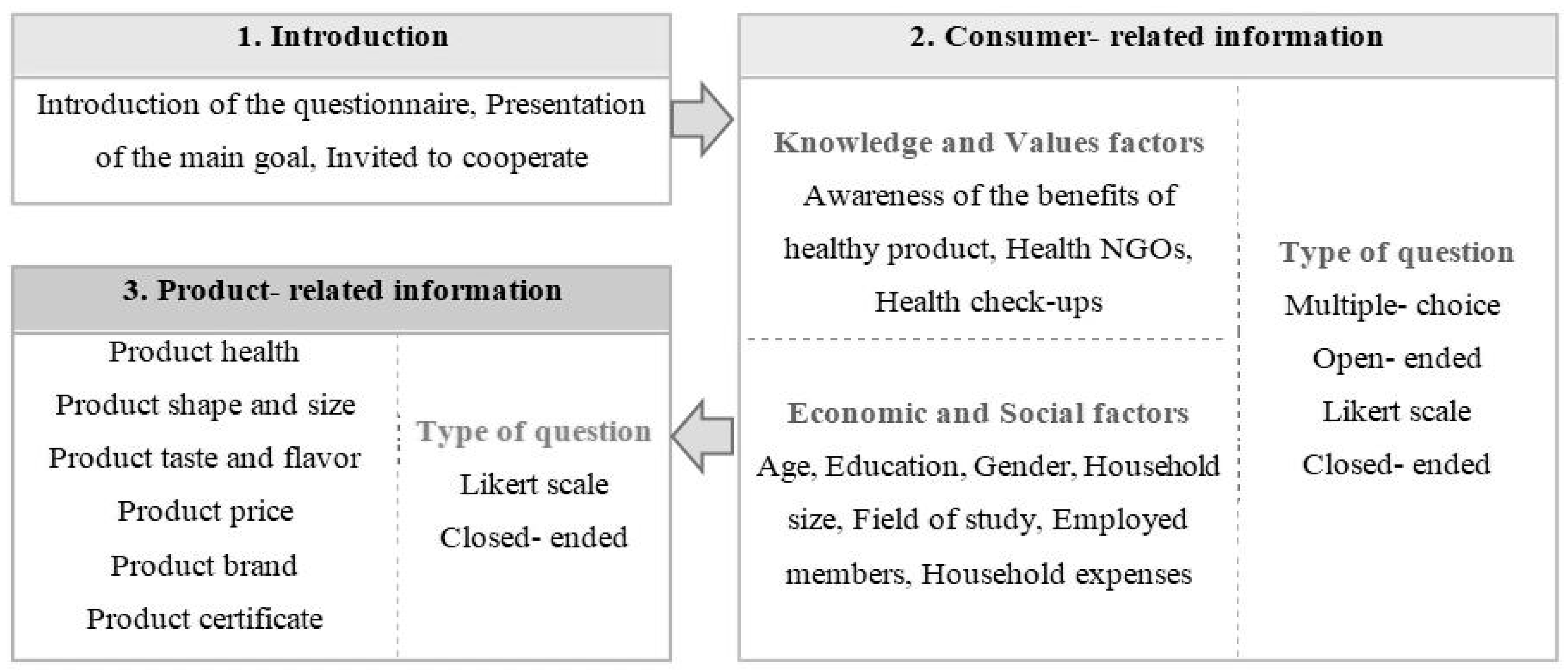

2.2. Data Collection

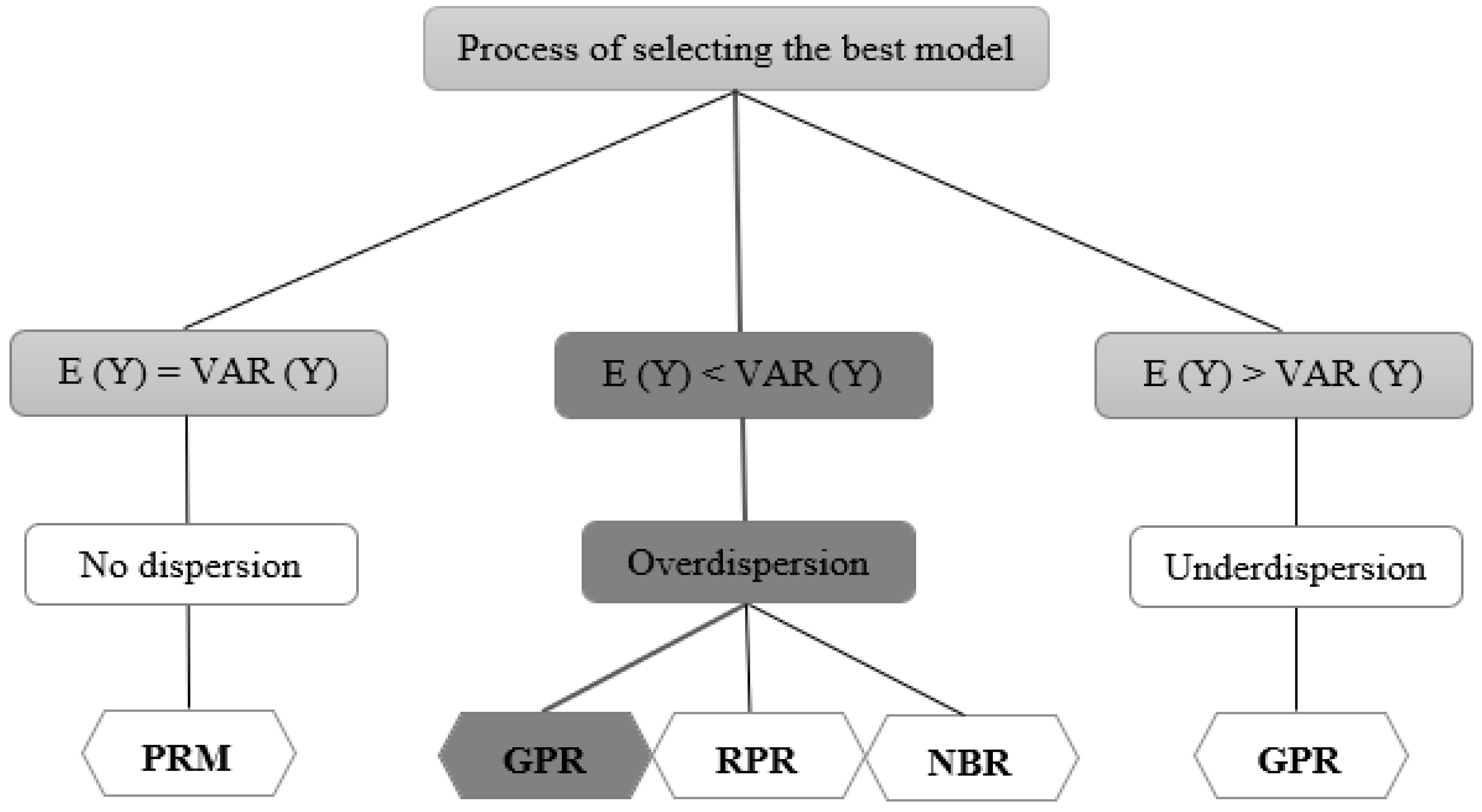

2.3. Count Models

2.3.1. Poisson Regression Model (PRM)

2.3.2. Negative Binomial Regression (NBR)

2.3.3. Generalized Poisson Regression (GPR)

2.3.4. Robust Poisson Regression (RPR)

2.4. Introduction of Count Model Variables (Dependent/Independent)

3. Results

3.1. Investigating the Effective Factors to Purchase Healthy-Labeled Agricultural Foods at a Premium by Consumers

3.2. Statistical Characteristics of Healthy Foods Consumers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Issues with label validation and certification: Some labels may not be properly validated or certified, which can lead to the dissemination of incorrect information about food products and undermine trust in labels [109].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teng, C.C.; Wang, Y.M. Decisional factors driving organic food consumption: Generation of consumer purchase intentions. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1066–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Ali, J. Factors affecting the consumers’ willingness to pay for health and wellness food products. J. Agric. Food Res. 2020, 2, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Kushwaha, A. Consumer’s perception and knowledge concerning safety of street food services in Pantnagar India. J. Food Saf. Hyg. 2017, 3, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Guertin, C.; Pelletier, L.; Pope, P. The validation of the Healthy and Unhealthy Eating Behavior Scale (HUEBS): Examining the interplay between stages of change and motivation and their association with healthy and unhealthy eating behaviors and physical health. Appetite 2019, 144, 104487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, D.Q.; Dung, D.V.; Dung, N.T.T. Factors Affecting the Consumers’ Purchase Decision Safe Food: Case Study in Vietnam. J. Manag. Econ. Stud. 2019, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Cavallo, C. Increasing healthy food choices through nudges: A systematic review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, R.; Bilali, H.E.; Debs, P.; Cardone, G.; Driouech, N. Food system sustainability and food security: Connecting the Dots. J. Food Secur. 2014, 2, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Sarkar, A.K. Impact of Health Consciousness and Food Safety Concern on Consumer Buying Behaviour–A Review on Organic Food Products. Asian J. Org. Med. Chem. 2022, 7, 676–686. [Google Scholar]

- Faal Amand, M.; Falsafian, A. Factors Influencing Willingness to Consume Safe Products in Tabriz County, case study: Cucumber and Tomato. Sustain. Agric. Sci. Res. 2022, 2, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Humaira, A.; Hudrasyah, H. Factors influencing the intention to purchase and actual purchase behavior of organic food. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 5, 581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Willer, H.; Lernoud, J. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL IFOAM—Organics International: Huntsville, AL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khodaverdizadeh, M. Investigating the influencing factors on the willingness to pay extra for cucumber consumers Organic in Urmia. J. Agric. Econ. Res. 2016, 9, 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, V.; Nikooy, M.; Khaledi, M. Strategies for the development of healthy food products market in Hamadan city. J. Agric. Econ. Dev. 2014, 27, 328–337. [Google Scholar]

- Yadavar, H.; Pakrooh, P. Determination of Effective Components on Consumer Behavior of Healthy and Organic Products Based on BASNEF Model (study Case: Agriculture students of Tabriz University). Agric. Ext. Educ. Res. 2021, 14, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kucher, A.; Heldak, M.; Kucher, L.; Fedorchenko, O.; Yurchenko, Y. Consumer willingness to pay a price premium for ecological goods: A case study from Ukraine. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2019, 7, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochaki, A.R.; Mansouri, H.; Ghorbani, M.; Rajabzadeh, M. Investigating factors affecting the desire to consume organic products in Mashhad city. Econ. Agric. Dev. 2013, 27, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Anjos, O. The link between the consumer and the innovations in food product development. Foods 2020, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, A.; Qureyshi, E. Organic farming and healthy eating. In Proceedings of the 4th National Congress of Organic Agriculture and Traditional, Mohaghegh Ardabili University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.S.; Legrand, W.; Sloan, P. Factors influencing healthy meal choice in Germany. Tourism Int. Interdiscip. J. 2006, 54, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto de Morais Watanabe, E.; Alfinito, S.; Castelo Branco, T.V.; Felix Raposo, C.; Athayde Barros, M. The Consumption of Fresh Organic Food: Premium Pricing and the Predictors of Willingness to Pay. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2023, 29, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Stricht, H.; Profeta, A.; Hung, Y.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ willingness to buy pasta with microalgae proteins–Which label can promote sales? Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 110, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britwum, K.; Bernard, J.C.; Albrecht, S.E. Does importance influence confidence in organic food attributes? J. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Meullenet, J.F.; Ricke, S.C. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic chicken breast: Evidence from choice experiment. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubhi, M.; Blake, M.; Nguyen, T.; Majmudar, I.; Moodie, M.; Ananthapavan, J. Consumer willingness to pay for healthier food products: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 24, e13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, R.; Singh, D. An analysis of factors affecting growth of organic food: Perception of consumers in Delhi-NCR (India). Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2308–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Meero, A.; Rahman, A.A.A.; Islam, K.A.; Zayed, N.M.; Hasan, K.R. An empirical study on the factors affecting organic food purchasing behavior in Bangladesh: Analyzing a few factors. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Huo, X. Consumer’s willingness to pay a premium for organic fruits in China: A double-hurdle analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystallis, A.; Chryssohoidis, G. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food: Factors that affect it and variation per organic product type. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Rani, N.; Devi, C.; Gupta, S. Factors affecting consumer purchase intentions of organic food through fuzzy AHP. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2022, 39, 1085–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Bokelmann, W.; Gowdru, N.V.; Dias, G. Factors influencing consumers’ willingness to pay for organic fruits and vegetables: Empirical evidence from a consumer survey in India. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Sarno, V. Consumer perception and corporate social responsibility: An explorative survey on food Italian market. Qual.-Access Success 2013, 14, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, B.T.H.; Truong, D.D. Factors influencing urban consumers’ premium payment for safe vegetables in Haiphong City, Vietnam. NeuroQuantology 2023, 21, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapa-Tankosić, J.; Ignjatijević, S.; Kranjac, M.; Lekić, S.; Prodanović, R. Willingness to pay for organic products on the Serbian market. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic food consumption in Poland: Motives and barriers. Appetite 2016, 105, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel Vidal, M.; Castellano-Tejedor, C. Identification of Marketing Strategies Influencing Consumers’ Perception of Healthy Food Products and Triggering Purchasing Decisions. Businesses 2022, 2, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hobbs, J.E.; Natcher, D.C. Assessing consumer willingness to pay for Arctic food products. Food Policy 2020, 92, 101846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velčovská, Š.; Del Chiappa, G. The food quality labels: Awareness and willingness to pay in the context of the Czech Republic. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2015, 63, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, M.A.; Javan, J.; Tavangar, M. Genealogy as a Method for Analyzing “City Role” Developments (Case Study: Mashhad). J. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 53, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Centre of Iran. 2021. Available online: https://www.amar.org.ir (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Ibeji, J.U.; Zewotir, T.; North, D.; Amusa, L. Modelling fertility levels in Nigeria using Generalized Poisson regression-based approach. Sci. Afr. 2020, 9, e00494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, D.; Kumawat, P.; Gómez–Déniz, E. A new count model generated from mixed Poisson transmuted exponential family with an application to health care data. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2017, 46, 11060–11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.C.; Wei, B.C.; Lin, J.G. Score tests for zero-inflated generalized Poisson mixed regression models. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 3478–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Famoye, F.; Wulu, J.T.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Singh, K.P. A rich family of generalized Poisson regression models with applications. Math. Comput. Simul. 2005, 69, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, O.A.; Shultz, S.D. Poisson Count Models to Adoption of Agricultural Explain and Natural Resource Management Technologies by Small Farmers in Central American Countries. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2000, 32, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Alvino, L.; Covino, D. This is not my jam: An Italian choice experiment on the influence of typical product attributes on consumers’ willingness to pay. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 54, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahzadeh, H.; Jahanaraei, Z.; Askarishahi, M.; Lotfi, M. Comparison of Efficiency in Generalized Poisson Regression Model and the Standard Poisson Regression Model in analyzing Fertility Behavior among Women, Kashan. Tolooebehdasht 2017, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Isgin, T.; Bilgic, A.; Forster, D.L.; Batte, M.T. Using count data models to determine the factors affecting farmers’ quantity decisions of precision farming technology adoption. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 62, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, C.M. Application of the Poisson and negative binomial models to thunderstorm and hail days probabilities in Nevada. Mon. Weather Rev. 1973, 101, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohamba, S.O.; Musara, J.P.; Bahta, Y.T.; Ogundeji, A.A. Drivers of Postharvest Loss among Citrus Farmers in Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: A Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) Regression Model Analysis. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeileis, A.; Kleiber, C.; Jackman, S. Regression models for count data in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.C.; Fu, C. Modeling crash frequency and severity using multinomial-generalized Poisson model with error components. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 50, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Berdine, G. Poisson regression. Southwest Respir. Crit. Care Chron. 2015, 3, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hardin, J.W.; Addy, C.L.; Vuong, Q.H. Testing approaches for overdispersion in Poisson regression versus the generalized Poisson model. Biom. J. 2007, 49, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.; Famoye, F. Generalized Poisson regression model. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 1992, 21, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.P.; Denuit, M.; Guillen, M. Models of insurance claim counts with time dependence based on generalization of Poisson and negative binomial distributions. Variance 2008, 2, 135–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstein, D.M. Using count data models in travel cost analysis with aggregate data. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1991, 73, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, E.; Ronchetti, E. Robust inference for generalized linear models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2001, 96, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klikocka, H.; Jarosz-angowska, A.; Nowak, A.; Skwarylo-Bednarz, B. Assessment of Poland food security in the context of agricultural production in 2010–2020. Agron. Sci. 2022, 3, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Sarić, M.M.; Klarin, I.; Rumbak, I.; Barić, I.C.; Ranilović, J.; Guiné, R. Motivation for health behaviour: A predictor of adherence to balanced and healthy food across different coastal Mediterranean countries. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 91, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.P.; Costa, S.A.; Brandão, T.R.; Rocha, A. Food consumption determinants and barriers for healthy eating at the workplace—A university setting. Foods 2021, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, R.M.; Balasubramanian, P. Understanding the decisional factors affecting consumers’ buying behaviour towards organic food products in Kerala. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 234, 00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Tariq, S. Association of perceived stress with healthy and unhealthy food consumption among teenagers. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1817–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munt, A.E.; Partridge, S.R.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The barriers and enablers of healthy eating among young adults: A missing piece of the obesity puzzle: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2016, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, D.; Boccia, F.; Sarno, V. Global warming and environmental agreements. Qual.-Access Success 2013, 14 (Suppl. S1), 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy-Pénzes, G.; Vincze, F.; Sándor, J.; Bíró, É. Does better health-related knowledge predict favorable health behavior in adolescents? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccia, F.; Sarnacchiaro, P. The Italian consumer and genetically modified food. Qual.-Access Success 2013, 14, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni, J.M.; Iorgulescu, R.I.; Mihnea, A. Understanding consumer motivations for buying sustainable agricultural products at Romanian farmers markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Verma, P. Factors influencing Indian consumers’ actual buying behaviour towards organic food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, P.; McCarthy, S.N.; McCarthy, M.B. The creation of a healthy eating motivation score and its association with food choice and physical activity in a cross sectional sample of Irish adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Fu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L. Consumers’ perceptions, purchase intention, and willingness to pay a premium price for safe vegetables: A case study of Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, E.; Coveney, J.; Meyer, S.B.; Wilson, A.M.; Webb, T. Managing uncertainty about food risks–Consumer use of food labeling. Appetite 2016, 107, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondelaers, K.; Verbeke, W.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Importance of health and environment as quality traits in the buying decision of organic products. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1120–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozoglu, M.; Bilgic, A.; Huang, C.L.; Florkowski, W.J.; Topuz, B.K. Urban households’ willingness to pay for milk safety in Samsun and Trabzon provinces of Turkey. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2379–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zeng, Y. Willingness to pay for the “Green Food” in China. Food Policy 2014, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sckokai, P.; Veneziani, M.; Moro, D.; Castellari, E. Consumer willingness to pay for food safety: The case of mycotoxins in milk. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2014, 3, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.T.; Huang, Y.S.; Lin, C.T.; Hsieh, Y. Measuring consumer’ willingness to pay for food safety certification labels of packaged rice. AIMS Agric. Food 2021, 6, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghjou, M.; Hayati, B.A.; Mohammadrezaei, R.; Pishbahar, A.; Dashti, G. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Potential Willingness to Pay a Premium for Safe Food Products (Case Study: Agricultural Administration of East Azerbaijan). J. Agric. Knowl. Sustain. Prod. 2011, 2, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, L.E.; Higuchi, A. Is fish worth more than meat? How consumers’ beliefs about health and nutrition affect their willingness to pay more for fish than meat. Food Qual. Prefer. J. 2018, 65, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Gholami, Z.A. Analysis of the determinants of consumers’ willingness to pay extra for organic products in Ghaemshahr city of Mazandaran province. In Proceedings of the 1st National Conference on Stable Agriculture and Natural Resources, Mazandaran; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Firoozzare, A.; Boccia, F.; Yousefian, N.; Ghazanfari, S.; Pakook, S. Understanding the role of awareness and trust in consumer purchase decisions for healthy food and products. J. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 121, 105275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.W.; Akter, N.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M. Organic foods purchase behavior among generation Y of Bangladesh: The moderation effect of trust and price consciousness. Foods 2021, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacârea, A.; Bacârea, V.C.; Cînpeanu, C.; Teodorescu, C.; Seni, A.G.; Guiné, R.P.; Tarcea, M. Demographic, anthropometric and food behavior data towards healthy eating in Romania. Foods 2021, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonneau, E.; Pelletier, L.; Begin, C.; Lamarche, B.; Bélanger, M.; Provencher, V.; Desroches, S.; Robitaille, J.; Vohl, M.C.; Couillard, C.; et al. Individuals with self-determined motivation for eating have better overall diet quality: Results from the PREDISE study. Appetite 2021, 165, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphonce, R.; Alfnes, F. Consumer willingness to pay for food safety in Tanzania: An incentive-aligned conjoint analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiciudean, D.; Funar, S.; Arion, F.; Chirla, G.; Man, A. The factors of influence over the consumer buying behaviour for organic food. Bull. UASVM Cluj-Napoca Hortic. 2012, 69, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yiridoe, E.K.; Bonti-Ankomah, S.; Martin, R.C. Comparison of consumer perceptions and preference toward organic versus conventionally produced foods: A review and update of the literature. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.M.; Soler, F. Knowledge and willingness to pay for organic food in Spain: Evidence from experimental auctions. Acta Agric. Scand Sect. C 2006, 3, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, R.; García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Millones-Liza, D.Y.; Villar-Guevara, M.; Toyohama-Pocco, G. Using the Theory of Perceived Value to Determine the Willingness to Consume Foods from a Healthy Brand: The Role of Health Consciousness. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firoozzare, A.; Ghazanfari, S.; Yousefian, N. Designing and analyzing the motivational risk profile of healthy food and agricultural product purchases. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 432, 139693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. The Effects of Organic Certification on Shoppers’ Purchase Intention Formation in Taiwan: A Multi-Group Analysis of Structural Invariance. Sustainability 2021, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, M.B.; Lal, D. Indian consumers’ attitudes towards purchasing organically produced foods: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 215, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangaro, D.; Chiranjeevi, K.; Rao, D.S. Factors Affecting Consumers to Buy Organic Food Products in Hyderabad and Secunderabad. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2017, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen, I. Procurement and consumption of local and organic food in the catering of a rural town. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.; Portilho, F.; Wilkinson, J.; Dubeux, V. Trust, participation and political consumerism among Brazilian youth. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakseresht, A.; Kaliji, S.A.; Canavari, M. Review of factors affecting consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Appetite 2022, 170, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Yu, D.; Zubair, M.; Rasheed, M.I.; Khizar, H.M.U.; Imran, M. Health consciousness, food safety concern, and consumer purchase intentions toward organic food: The role of consumer involvement and ecological motives. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Alam, A.; Ali, J. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Purchase Behaviour for Health and Wellness Food Products in an Emerging Market. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021, 22, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing organic food consumption: An integrating model of drivers and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F. Genetically Modified Organisms: What Issues in the Italian Market? Qual.-Access Success 2015, 16, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kusdiyanto, K.; Saputro, E.P.; Sholahuddin, M.; Mabruroh, M.; Irawati, Z.; Murwanti, S.; Setyaningrum, D.P. Identification of intention to buy healthy food. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 5, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Nogueira, S. Willingness to pay more for green products: A critical challenge for Gen Z. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pham, T.L.; Dang, V.T. Environmental consciousness and organic food purchase intention: A moderated mediation model of perceived food quality and price sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royne, M.B.; Levy, M.; Martinez, J. The public health implications of consumers’ environmental concern and their willingness to pay for an eco-friendly product. J. Consum. Aff. 2011, 45, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesse, M.B.; Van Den Berg, M. Consumer Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Behavior in Urban Ethiopia: A Comprehensive Study. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messer, K.D.; Costanigro, M.; Kaiser, H.M. Labeling food processes: The good, the bad and the ugly. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2017, 39, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri Cornish, L.; Moraes, C. The impact of consumer confusion on nutrition literacy and subsequent dietary behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.; Quinlan, J.J. Consumer knowledge and behaviors regarding food date labels and food waste. Food Control J. 2020, 115, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, T.A. Consumers find food labels confusing and too small to read. Pract. Diabetes Int. 2011, 28, 261–264c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, G.; Schramm, M.; Spiller, A. The reliability of certification: Quality labels as a consumer policy tool. J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.V.; Fernandes, A.C.; Chaddad, M.C.C.; Uggioni, P.L.; Bernardo, G.L.; Proença, R.P. Is the List of Ingredients a Source of Nutrition and Health Information in Food Labeling? A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, D.; Boccia, F. Potentialities of new agri-biotechnology for sustainable nutrition. Riv. Di Studi Sulla Sostenibilità 2016, 2, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Code | Variable Type |

|---|---|---|

| Economic and Social | ||

| Age (Years) | AGE | Quantitative (Continuous) |

| Gender | GENDER | Dummy (Female = 0, Male = 1) |

| Education (Years) | EDUCATION | Quantitative (Continuous) |

| Field of study 1 | FIELD OF STUDY | Dummy (Fields related to medicine, paramedicine, and agriculture = 1, Otherwise = 0) |

| Household size (Person) | HSIZE | Quantitative (Continuous) |

| Employed household members | EMPLOYED MEMBERS | Quantitative (Continuous) |

| The presence of individuals over 60 years old in the household | ELDERLY | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| The presence of children under 5 years old in the household | CHILDREN | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Household expenses (dollars per month) | EXPENSES | Quantitative (Continuous) |

| Property position 2 | PROPERTY | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Food-related | ||

| Importance of food shape and size | SHAPE & SIZE | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Importance of food taste and flavor | TASTE & FLAVOR | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Importance of food price | PRICE | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Importance of food healthiness | HEALTH | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Trust in a brand of healthy food | BRAND | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Governance function | ||

| The level of government supervision on the health of foods | GOVERNMENT SUPERVISION | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Health behavior and awareness | ||

| Implement annual health check-ups | CHECK-UPS | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Membership in health NGOs | HEALTH NGOs | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Environmental behavior and awareness | ||

| The level of knowledge about the harmful effects of chemical fertilizers and toxins on human health | KNOWLEDGE | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Practicing the 5Rs 3 | 5Rs | Dummy (Yes = 1, No = 0) |

| Worry about remaining toxins and fertilizers in foods | TOXINS & FERTILIZERS | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Awareness of the harmful effects of fast food on health | FAST FOOD | Ordered (Never = 0, Low = 1, Middle = 2, High = 3) |

| Number of Healthy Foods | Frequently Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (People) | Percentage (%) | Cumulative (%) | |

| 0 | 46 | 12.81 | 12.81 |

| 1 | 12 | 3.34 | 16.16 |

| 2 | 14 | 3.90 | 20.06 |

| 3 | 15 | 4.18 | 24.23 |

| 4 | 11 | 3.06 | 27.30 |

| 5 | 13 | 3.62 | 30.92 |

| 6 | 9 | 2.51 | 33.43 |

| 7 | 11 | 3.06 | 36.49 |

| 8 | 17 | 4.74 | 41.23 |

| 9 | 11 | 3.06 | 44.29 |

| 10 | 37 | 10.31 | 54.60 |

| 11 | 163 | 45.40 | 100 |

| Total | 359 | 100 | - |

| Food 1 Name | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato | 0.45 | 77 (21.44) | 0.53 | 0.56 | 81 (22.56) | 0.08 | 17.78 |

| Melon | 0.41 | 95 (26.46) | 0.48 | 0.45 | 53 (14.76) | 0.07 | 17.07 |

| Cucumber | 0.37 | 96 (26.74) | 0.44 | 0.45 | 63 (17.54) | 0.07 | 18.92 |

| Onion | 0.37 | 92 (25.62) | 0.44 | 0.45 | 58 (16.15) | 0.07 | 18.92 |

| Apple | 0.56 | 99 (27.57) | 0.64 | 0.64 | 49 (13.64) | 0.08 | 14.29 |

| Potato | 0.56 | 113 (31.47) | 0.62 | 0.60 | 55 (15.32) | 0.06 | 10.71 |

| Pepper | 1.32 | 131 (36.49) | 1.47 | 1.50 | 92 (25.62) | 0.15 | 11.36 |

| Rice | 5.66 | 124 (34.54) | 6.12 | 6.03 | 70 (19.49) | 0.46 | 8.13 |

| Strawberry | 4.15 | 155 (43.17) | 4.45 | 4.33 | 59 (16.43) | 0.30 | 7.23 |

| Walnut | 6.41 | 126 (35.09) | 6.9 | 6.79 | 58 (16.15) | 0.49 | 7.64 |

| Saffron | 6.79 | 118 (32.86) | 7.26 | 7.16 | 79 (22) | 0.47 | 6.92 |

| Column A: The current price of the regular food on the market (USD 2). | |||||||

| Column B: The frequency and percentage of individuals who are willing to purchase the food with a healthy label and no premium. | |||||||

| Column C: The average maximum price declared by individuals in purchasing a healthy-labeled food (USD). | |||||||

| Column D: The mode of the maximum price declared by individuals in purchasing a healthy-labeled food (USD). | |||||||

| Column E: The frequency and percentage of individuals interested in purchasing a healthy-labeled food at the mode price. | |||||||

| Column F: The difference between the average of the maximum price and the current price (C − A) (USD). | |||||||

| Column G: The percentage of price increase people are willing to pay for a healthy-labeled food compared to its current price [((C − A)/A) × 100]. | |||||||

| Variables | Group Frequency (%) | Mean | Std. Dev | Max | Min | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Age | 30.63 | 9.07 | 63 | 18 | ||||

| Gender | 219 (61) | 140 (39) | ||||||

| Education | 14.88 | 3.07 | 22 | 2 | ||||

| Field of study | 304 (84.68) | 55 (15.32) | ||||||

| Hsize | 4.41 | 2.07 | 15 | 1 | ||||

| Employed members | 2.14 | 1.13 | 8 | 1 | ||||

| Elderly | 244 (67.97) | 115 (32.03) | ||||||

| Children | 258 (71.87) | 101 (28.13) | ||||||

| Expenses | 282.39 | 173.45 | 1132.07 | 18.86 | ||||

| Property | 116 (32.31) | 243 (67.69) | ||||||

| Shape and Size | 340 (94.71) | 19 (5.29) | ||||||

| Taste and Flavor | 0 | 4 (1.11) | 91 (25.35) | 264 (73.54) | ||||

| Price | 9 (2.51) | 20 (5.57) | 175 (48.75) | 155 (43.17) | ||||

| Health | 0 | 6 (1.67) | 56 (15.60) | 297 (82.73) | ||||

| Brand | 2 (0.56) | 86 (23.96) | 226 (62.95) | 45 (12.53) | ||||

| Government supervision | 72 (20.06) | 191 (53.20) | 89 (24.79) | 7 (1.95) | ||||

| Check-ups | 125 (34.82) | 234 (65.18) | ||||||

| Health NGOs | 340 (94.71) | 19 (5.29) | ||||||

| Knowledge | 47 (13.09) | 93 (25.91) | 142 (39.55) | 77 (21.45) | ||||

| 5Rs | 120 (33.43) | 239 (66.57) | ||||||

| Toxins and Fertilizers | 3 (0.84) | 49 (13.64) | 84 (23.40) | 223 (62.12) | ||||

| Fast food | 2 (0.56) | 40 (11.14) | 136 (37.88) | 181 (50.42) | ||||

| Estimated Coefficient | T | Prob | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted value | 0.099 | 5.68 | 0.000 |

| Model | Robust Poisson | Generalized Poisson | Negative Binomial Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | IRR | Z | Coefficient | IRR | Z | Coefficient | IRR | Z | |

| Age | 0.0051 | 1.0051 | 1.58 | 0.0064 | 1.0064 | 1.55 | 0.0058 | 1.0058 | 1.33 | |

| Gender | −0.0906 | 0.9133 | −1.34 | −0.0465 | 0.9544 | −0.55 | −0.1519 * | 0.0859 | −1.68 | |

| Education | 0.0036 | 1.0036 | 0.45 | 0.0023 | 1.0023 | 0.25 | 0.0009 | 1.0009 | 0.09 | |

| Field of study | 0.2085 *** | 1.2319 | 3.05 | 0.2803 *** | 1.3236 | 3.14 | 0.2292 ** | 1.2576 | 2.21 | |

| Hsize | −0.0517 ** | 0.9495 | −2.14 | −0.0592 ** | 0.9424 | −2.35 | −0.0619 ** | 0.9399 | −2.35 | |

| Employed members | 0.0711 ** | 1.0737 | 2.08 | 0.0706 | 1.0732 | 1.60 | 0.0753 * | 1.0782 | 1.72 | |

| Elderly | −0.1308 ** | 0.8773 | −1.98 | −0.1623 ** | 0.8501 | −2.17 | −0.1501 * | 0.8605 | −1.88 | |

| Children | 0.0644 | 1.0665 | 0.92 | 0.0565 | 1.0581 | 0.69 | 0.0694 | 1.0718 | 0.78 | |

| Expenses | −0.0107 ** | 0.9892 | −2.01 | −0.0157 ** | 0.9843 | −2.52 | −0.0111 | 0.9888 | −1.63 | |

| Property | 0.0283 | 1.0287 | 0.43 | 0.0166 | 1.0168 | 0.21 | 0.0180 | 1.0182 | 0.22 | |

| Shape and Size | 0.3799 *** | 1.4621 | 4.49 | 0.4425 *** | 1.5566 | 3.29 | 0.4235 *** | 1.5274 | 2.67 | |

| Taste and Flavor | −0.1523 ** | 0.8587 | −2.34 | −0.1932 ** | 0.8242 | −2.43 | −0.1763 * | 0.8383 | −1.89 | |

| Price | −0.1188 *** | 0.8879 | −2.62 | −0.1516 *** | 0.8592 | −2.87 | −0.1404 ** | 0.8690 | −2.47 | |

| Health | Middle | 2.7715 *** | 15.9841 | 3.91 | 2.8471 *** | 17.2382 | 3.98 | 2.6624 *** | 14.3311 | 4.74 |

| High | 2.6785 *** | 14.5635 | 3.77 | 2.7426 *** | 15.5281 | 3.83 | 2.5463 *** | 12.7603 | 4.54 | |

| Brand | 0.1151 ** | 1.1219 | 2.32 | 0.1108 * | 1.1172 | 1.83 | 0.1070 * | 1.1129 | 1.76 | |

| Government supervision | 0.0991 *** | 1.1042 | 2.54 | 0.1212 *** | 1.1289 | 2.63 | 0.1081 ** | 1.1141 | 2.15 | |

| Check−ups | 0.0042 | 1.0042 | 0.06 | 0.0145 | 1.0146 | 0.18 | 0.0183 | 1.0185 | 0.23 | |

| Health NGOs | 0.0873 | 1.0912 | 1.00 | 0.1631 | 1.1771 | 1.23 | 0.0933 | 1.0977 | 0.60 | |

| Knowledge | 0.0536 | 1.0551 | 1.59 | 0.0740 * | 1.0768 | 1.92 | 0.0493 | 1.0506 | 1.24 | |

| 5Rs | 0.1651 ** | 1.1796 | 2.48 | 0.2135 *** | 1.2381 | 2.82 | 0.1642 ** | 1.1784 | 2.10 | |

| Toxins and Fertilizers | 0.0220 | 1.0223 | 0.49 | 0.0311 | 1.0316 | 0.61 | 0.0575 | 1.0592 | 1.02 | |

| Fast food | 0.1286 *** | 1.1372 | 2.73 | 0.1640 *** | 1.1782 | 3.07 | 0.1405 *** | 1.1509 | 2.65 | |

| Property | 0.0283 | 1.0287 | 0.43 | 0.0166 | 1.0168 | 0.21 | 0.0180 | 1.0182 | 0.22 | |

| Constant | −0.9487 | 0.3872 | −1.17 | −0.9858 | 0.3731 | −1.16 | −0.7245 | 0.4845 | −1.00 | |

| α (Scattering coefficient) | 0.4030 | 0.2576 | ||||||||

| Prob (Scattering coefficient) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Criterion | Robust Poisson | Generalized Poisson | Negative Binomial |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | 2264.38 | 2105.47 | 2126.03 |

| BIC | 2357.57 | 2202.56 | 2223.12 |

| Log Likelihood | −1108.19 | −1027.73 | −1038.02 |

| Number of significant variables | 16 | 13 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghazanfari, S.; Firoozzare, A.; Covino, D.; Boccia, F.; Palmieri, N. Exploring Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Healthy-Labeled Foods at a Premium Price. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166895

Ghazanfari S, Firoozzare A, Covino D, Boccia F, Palmieri N. Exploring Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Healthy-Labeled Foods at a Premium Price. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166895

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhazanfari, Sima, Ali Firoozzare, Daniela Covino, Flavio Boccia, and Nadia Palmieri. 2024. "Exploring Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Healthy-Labeled Foods at a Premium Price" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166895

APA StyleGhazanfari, S., Firoozzare, A., Covino, D., Boccia, F., & Palmieri, N. (2024). Exploring Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Healthy-Labeled Foods at a Premium Price. Sustainability, 16(16), 6895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166895