Smell the Perfume: Can Blockchain Guarantee the Provenance of Key Product Ingredients in the Fragrance Industry?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Analysis of Traceability-Related Claims Made by Brands and Manufacturers of Fragrance Products

3.2. Expert Interviews

3.2.1. Selection of Interview Respondents

3.2.2. Design of Semi-Structured Interviews

- The importance of traceability and transparency in the fragrance supply chain, particularly related to product provenance or origin, ethical or responsible sourcing and sustainability.

- The major complexities or issues that arise in the context of traceability and transparency related to product provenance or origin, sustainability and ethical or responsible sourcing.

- The potential usefulness of blockchain technology in the fragrance industry supply chain for traceability and transparency on provenance or origin, sustainability and ethical or responsible sourcing.

- Whether the implementation of blockchain technology can improve on existing weaknesses and strengthen current fragrance industry supply chain processes.

- The type of blockchain (i.e., private, consortium or public) that may be most suitable for the fragrance industry.

- Whether final customers will trust or value blockchain-enabled transparency and traceability assurances more than certificates issued by fragrance companies, RM suppliers or certifying agencies.

- Whether blockchain technology should be viewed as an addition to existing information systems or a complete disruption.

- The challenges and obstacles that may be experienced by a fragrance company seeking to implement blockchain technology.

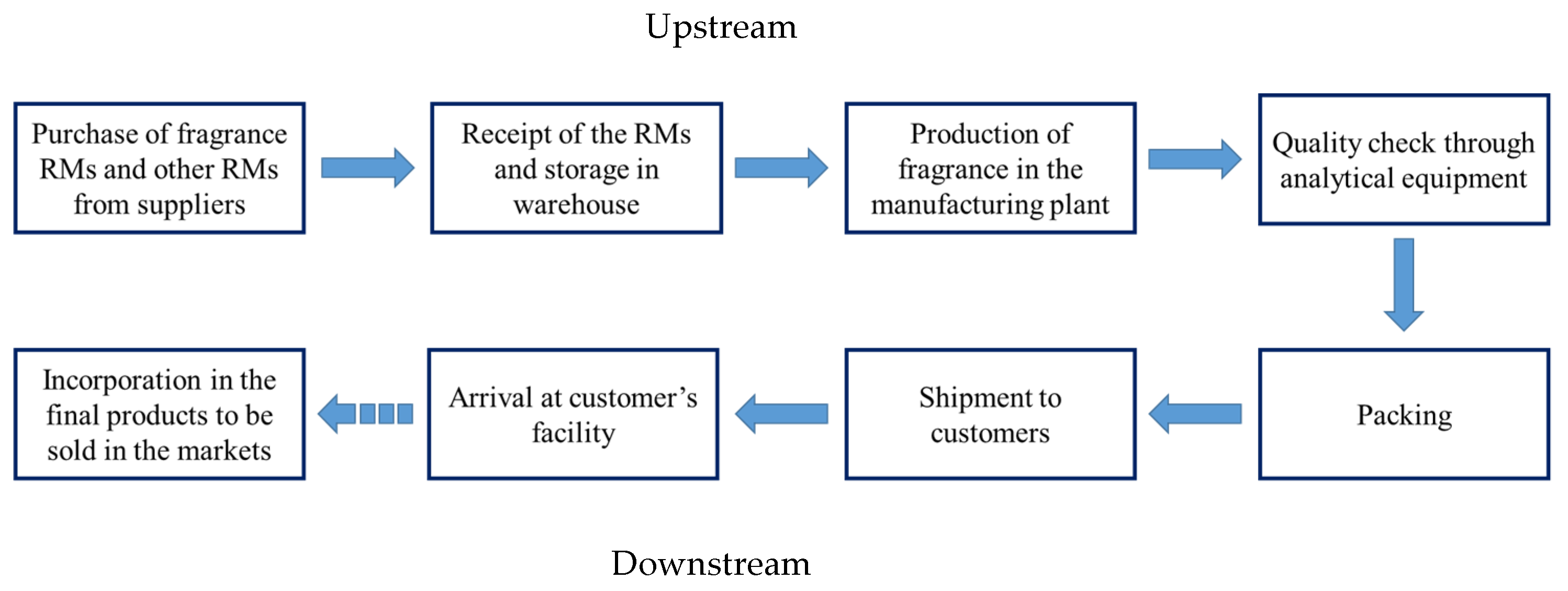

4. Analysis of Traceability-Related Claims on Fragrance Products and Raw Materials

5. Analysis of Interview Responses

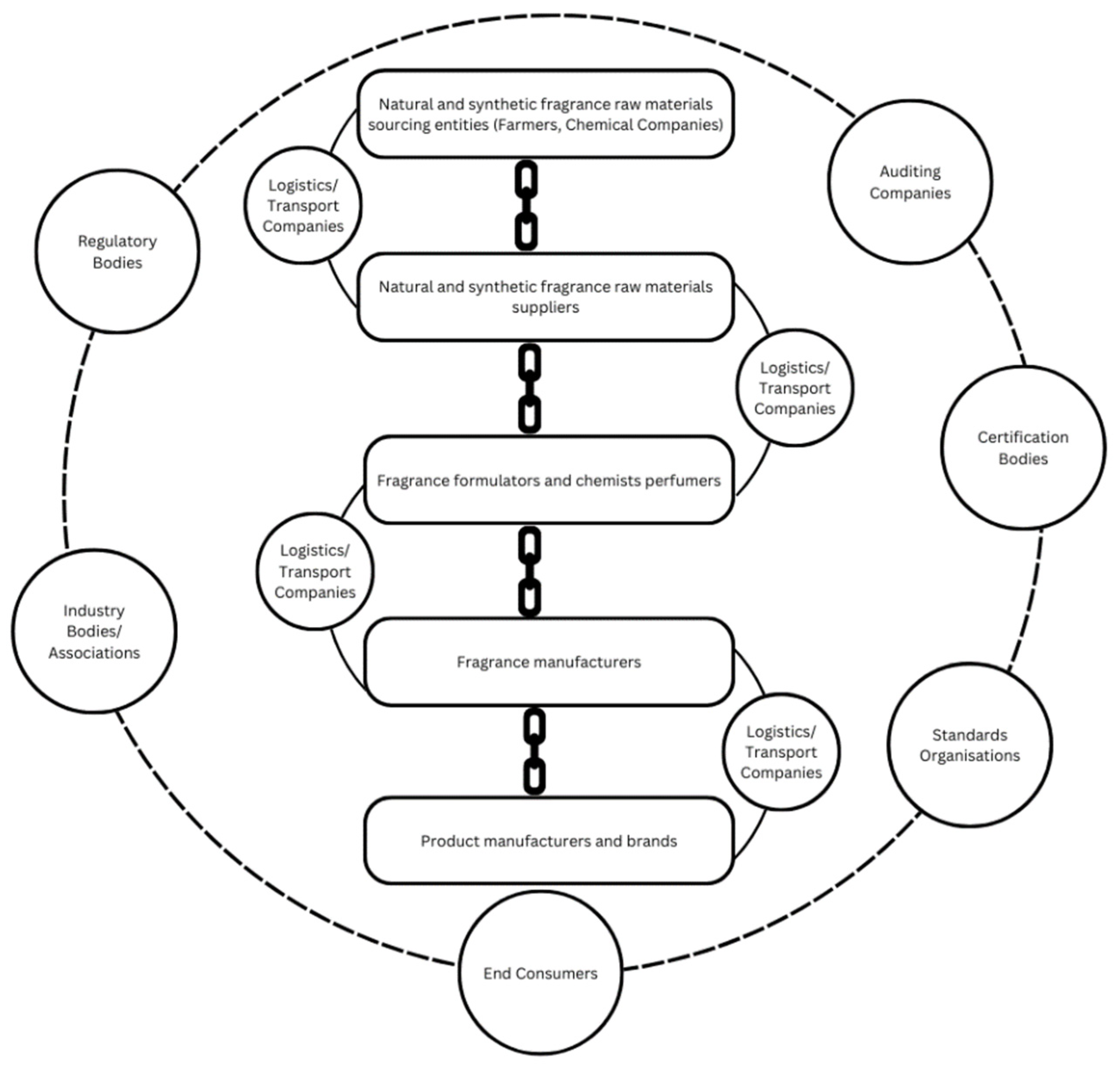

5.1. Importance of Supply Chain Traceability, Transparency, Provenance, Ethical Sourcing, Authenticity and Sustainability in the Fragrance Industry

5.2. Major Traceability and Transparency Challenges in the Fragrance Sector and the Potential Usefulness and Application of Blockchain Technology Solutions to Address Them

5.3. Industry and End-Consumer Trust in Blockchain-Enabled Traceability and Transparency

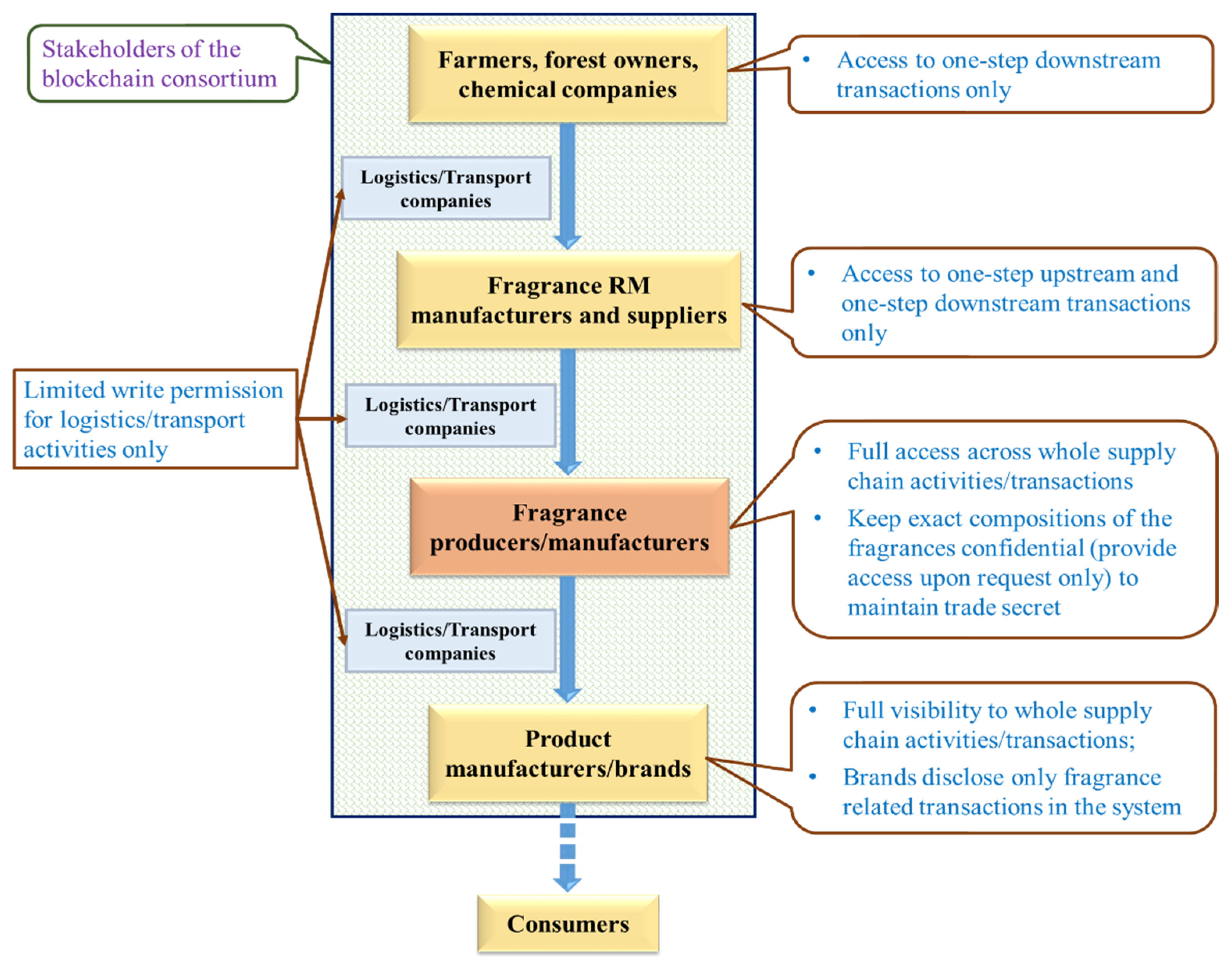

5.4. The Type of Blockchain Solution Suitable for the Fragrance Industry and Relationship with Existing Systems

5.5. Challenges in Implementing Blockchain Technology in the Fragrance Industry

6. How Blockchain Can Support the Assurances Made on Fragrance Ingredients and Supply Chains

6.1. Practical Implications for Blockchain-Enabled Traceability in the Fragrance Industry

6.2. Challenges to Realize Blockchain Traceability Solutions in the Fragrance Industry

7. Summary of Findings

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Product | Claims | Classification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eau de Parfum Naturelle by Chloé |

|

| [108,109] |

| Nomade Eau de Parfum Naturelle by Chloé |

|

| [110] |

| Atelier des Fleurs Ylang Cananga by Chloé |

|

| [111] |

| My Way Intense by Giorgio Armani |

|

| [19,20] |

| To Be Green by Police |

|

| [112] |

| Phantom by Paco Rabanne |

|

| [93,113] |

| God Is A Woman by Ariana Grande |

|

| [114] |

| Downy Premium Parfum Adorable Bouquet Concentrate Fabric Conditioner by Procter & Gamble |

|

| [115] |

| Hygiene Expert Care Life Nature Concentrate Fabric Softener Sunrise Kiss by IP One |

|

| [116] |

| Skip Essence de la Nature Ecological Liquid Laundry Detergent by Unilever |

|

| [117] |

| Seventh Generation Clementine Zest & Lemongrass Dishwashing Liquid by Unilever |

|

| [21] |

| Shower Gels by Original Source |

|

| [118] |

| SoKlin Liquid Detergent Nature series by Wings |

|

| Claims on the pack of the products |

| Downy Nature Fabric Softener Pomegranate and Vanilla by P&G |

|

| [119,120] |

| Les Fleurs Du Dechet—I Am Trash By Etat Libre D’orange Paris |

|

| [121] |

| Vigilante by St. Rose |

|

| [122] |

| Eau de Parfums by Floratropia Paris |

|

| [123] |

| Eau de Parfums by Henry Rose |

|

| [92] |

| Girl by Rochas |

|

| [124] |

| L’interdit Eau de Parfum Rouge by Givenchy |

|

| [90,91] |

| Polo Earth by Ralph Lauren |

|

| [125] |

| Love Home and Planet products (fabric care, dishwashing, surface cleaner) by Unilever |

|

| [126] |

| Love Beauty and Planet products (hand lotion, body mist, body cream, body scrub, hand wash, shampoo, hair conditioner, deodorant stick, hand sanitizer, bath/shower gel, bath bomb) by Unilever |

|

| [127] |

References

- Treiblmaier, H.; Rejeb, A.; Ahmed, W.A.H. Blockchain Technologies in the Digital Supply Chain. In The Digital Supply Chain; MacCarthy, B.L., Ivanov, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 127–144. ISBN 978-0-323-91614-1. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, G.; Enea, M.; Muriana, C. The Expected Value of the Traceability Information. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 244, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Traceability in a Food Supply Chain: Safety and Quality Perspectives. Food Control 2014, 39, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K. Supply Chain Traceability Systems—Robust Approaches for the Digital Age. In The Digital Supply Chain; MacCarthy, B.L., Ivanov, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 163–179. ISBN 978-0-323-91614-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hastig, G.M.; Sodhi, M.S. Blockchain for Supply Chain Traceability: Business Requirements and Critical Success Factors. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blockchain-Based Agri-Food Supply Chain Management: Case Study in China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.A.H.; MacCarthy, B.L.; Treiblmaier, H. Why, Where and How Are Organizations Using Blockchain in Their Supply Chains? Motivations, Application Areas and Contingency Factors. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 1995–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Choi, T.-M.; Somani, S.; Butala, R. Blockchain Technology in Supply Chain Operations: Applications, Challenges and Research Opportunities. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 142, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquette, I.; Blockchain Fails to Gain Traction in the Enterprise. Wall Str. J. 2022. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/blockchain-fails-to-gain-traction-in-the-enterprise-11671057528 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Anderson, E.; Li, J. Fragrances—Overview. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/fragrances-overview (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Herz, R.S.; Larsson, M.; Trujillo, R.; Casola, M.C.; Ahmed, F.K.; Lipe, S.; Brashear, M.E. A Three-Factor Benefits Framework for Understanding Consumer Preference for Scented Household Products: Psychological Interactions and Implications for Future Development. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2022, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Market Analysis Report Perfume Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report, 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/perfume-market (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Petruzzi, D. Global Market Value for Natural/Organic Cosmetics and Personal Care in 2020–2031. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/673641/global-market-value-for-natural-cosmetics/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Roberts, R. 2022 Beauty Industry Trends & Cosmetics Marketing: Statistics and Strategies for Your Ecommerce Growth. Available online: https://commonthreadco.com/blogs/coachs-corner/beauty-industry-cosmetics-marketing-ecommerce (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Marchessou, S.; Spagnuolo, E. Taking a Good Look at the Beauty Industry|McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/taking-a-good-look-at-the-beauty-industry (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Culliney, K. Clean Beauty 2020: Two-Thirds of Women Worldwide Want Greater Label Transparency, Finds Survey. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsdesign-europe.com/Article/2020/06/10/Clean-beauty-labels-lack-transparency-say-consumers-in-Bazaarvoice-Influenster-survey (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Cosmetics Business Thousands of Students around the World Will Benefit from Iberchem’s Roots Programme. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsbusiness.com/news/article_page/Thousands_of_students_around_the_world_will_benefit_from_Iberchems_Roots_programme/204948 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Parkhouse, A. A Look at LVMH’s Blockchain Consortium. Available online: https://hypebeast.com/2022/8/lvmh-aura-blockchain-luxury-fashion (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Armani Beauty My Way Eau de Parfum Intense Women’s Perfume—Armani Beauty. Available online: https://www.giorgioarmanibeauty-usa.com/fragrances/womens-perfume/my-way/my-way-intense/A22599.html (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Wilkins, B. Want to Do Your Part for the Planet? Find Your Own Way, Helped with a Spritz of This “sustainably Conscious” Scent. Available online: https://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/bc/article/armani-my-way (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- SeventhGeneration Dish Soap—Clementine Zest & Lemongrass|Seventh Generation. Available online: https://www.seventhgeneration.com/dish-liquid-lemongrass-clementine-zest?bvstate=pg:2/ct:q (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- GovUK Unilever’s ‘Green’ Claims Come under CMA Microscope. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/unilevers-green-claims-come-under-cma-microscope (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- GovInfo, H.R. 3622 (IH)—Cosmetic Supply Chain Transparency Act of 2023—Content Details. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BILLS-118hr3622ih (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- BCPP Cosmetic Supply Chain Transparency Act. Breast Cancer Prevention Partners (BCPP). 2023. Available online: https://www.bcpp.org/resource/cosmetic-supply-chain-transparency-act/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Martínez-Guido, S.I.; González-Campos, J.B.; del Río, R.E.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M.; Nápoles-Rivera, F.; Serna-González, M.; El-Halwagi, M.M. A Multiobjective Optimization Approach for the Development of a Sustainable Supply Chain of a New Fixative in the Perfume Industry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2380–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palefsky, I. Flagrance Application In Consumer Products. Flagrance Appl. Consum. Prod. 1980, 4, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pybus, D.H.; Sell, C.S. The Chemistry of Fragrances; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-0-85404-528-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alpha Aromatics How Perfume Is Made—A Master Perfumers’ Industry Guide. Available online: https://www.alphaaromatics.com/blog/how-perfume-is-made-the-perfumers-industry-guide/ (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- PwC The Value of Fragrance: A Socio-Economic Contribution Study for the Global Fragrance Industry. Available online: https://ifrafragrance.org/docs/default-source/policy-documents/pwc-value-of-fragrance-report-2019.pdf?sfvrsn=b3d049c8_0 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Hänke, H.; Barkmann, J.; Blum, L.; Franke, Y.; Martin, D.A.; Niens, J.; Osen, K.; Uruena, V.; Witherspoon, S.A.; Wurz, A. Socio-Economic, Land Use and Value Chain Perspectives on Vanilla Farming in the SAVA Region (North-Eastern Madagascar): The Diversity Turn Baseline Study (DTBS); Diskussionsbeitrag: Göttingen, Germany,, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B.M. Regulatory and Quality Issues with the Essential Oils Supply Chain. In Medicinal and Aromatic Crops: Production, Phytochemistry, and Utilization; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 1218, pp. 27–48. ISBN 978-0-8412-3127-6. [Google Scholar]

- González-Aguirre, J.-A.; Solarte-Toro, J.C.; Cardona Alzate, C.A. Supply Chain and Environmental Assessment of the Essential Oil Production Using Calendula (Calendula officinalis) as Raw Material. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccardelli, M.; Roscigno, G.; Pane, C.; Celano, G.; Di Matteo, M.; Mainente, M.; Vuotto, A.; Mencherini, T.; Esposito, T.; Vitti, A.; et al. Essential Oils and Quality Composts Sourced by Recycling Vegetable Residues from the Aromatic Plant Supply Chain. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarthy, B.L.; Ivanov, D. The Digital Supply Chain—Emergence, Concepts, Definitions, and Technologies. In The Digital Supply Chain; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Proposal for a Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and Annex. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/proposal-directive-corporate-sustainability-due-diligence-and-annex_en (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG Reporting Quantity, Quality and Performance: Where to Now for Environmental Policy and Practice? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boissieu, E.; Kondrateva, G.; Baudier, P.; Ammi, C. The Use of Blockchain in the Luxury Industry: Supply Chains and the Traceability of Goods. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 34, 1318–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanolli, L. Why Smelling Good Could Come with a Cost to Health. The Guardian. 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/23/fragrance-perfume-personal-cleaning-products-health-issues (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Nast, C. Perfume makers are fighting back against an illegal fake scent boom. Wired UK. 2020. Available online: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/fake-perfume (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Deloitte Is Your Supply Chain Trustworthy? Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/xe/en/insights/focus/supply-chain/issues-in-global-supply-chain.html (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Brown, S. Supply Chain 2020 Special Report—Supply Chain Visbility Boosts Consumer Trust and Even Sales; MIT Management Sloan School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 17–20. Available online: https://mitsloan.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2020-02/Supply%20Chain%20-%20ROUNDUP-DESIGN-5.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRA Fragrance Introduction—Our Roles and Priorities. Available online: https://ifrafragrance.org/priorities/introduction (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Lambert, D.M.; Schwieterman, M.A. Supplier Relationship Management as a Macro Business Process. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasago TaSuKI Update|Takasago International Corporation. Available online: https://www.takasago.com/en/sustainability/visitor/project.html (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Sustainable Vanilla Initiative Sustainable Vanilla Initiative (SVI). Available online: https://www.idhsustainabletrade.com/sustainable-vanilla-initiative-svi/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Brintrup, A.; Kosasih, E.E.; MacCarthy, B.L.; Demirel, G. Chapter 22—Digital Supply Chain Surveillance: Concepts, Challenges, and Frameworks. In The Digital Supply Chain; MacCarthy, B.L., Ivanov, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 379–396. ISBN 978-0-323-91614-1. [Google Scholar]

- Herich, D. Validating Believable Beauty Claims. Available online: https://www.gcimagazine.com/consumers-markets/article/22366404/validating-believable-beauty-claims (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Gapper, J. Investigators Sniff out the Hidden Fragrance Industry. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/96dd63ed-f5b9-4d96-9566-5dda30bca163 (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Wowak, K.D.; Craighead, C.W.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. JTracing Bad Products in Supply Chains: The Roles of Temporality, Supply Chain Permeation, and Product Information Ambiguity. J. Bus. Logist. 2016, 37, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifferlin, A. That Makeup Ad Is Probably Lying to You. Available online: https://time.com/3973031/cosmetic-ads/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Hooker, N.; Simons, C.T.; Parasidis, E. “Natural” Food Claims: Industry Practices, Consumer Expectations, and Class Action Lawsuits; Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijswijk, W.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer Needs and Requirements for Food and Ingredient Traceability Information. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.-H. Effects of Ingredients, Names and Stories about Food Origins on Perceived Authenticity and Purchase Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasakthy, A.; Norcross, L.; (DeMuro) Romano, C.; Carson, R.T. A Review of Patient-Reported Outcome Labeling of FDA-Approved New Drugs (2016–2020): Counts, Categories, and Comprehensibility. Value Health 2022, 25, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acreman, S. Show Us Your Traces: Traceability as a Measure for the Political Acceptability of Truth-Claims. Contemp. Polit. Theory 2015, 14, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.A.H.; MacCarthy, B.L. Blockchain-Enabled Supply Chain Traceability—How Wide? How Deep? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 263, 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, B.; Musilek, P. A Comprehensive Review of Blockchain Consensus Mechanisms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43620–43652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hoang, D.T.; Hu, P.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Wang, P.; Wen, Y.; Kim, D.I. A Survey on Consensus Mechanisms and Mining Strategy Management in Blockchain Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 22328–22370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buterin, V. On Public and Private Blockchains. On Public and Private Blockchains, Ethereum Foundation Blog. 2015. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2015/08/07/on-public-and-private-blockchains (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.H.; Beynon-Davies, P. Understanding Blockchain Technology for Future Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Gera, S.; Saxena, M. Mitigating Security Risks on Privacy of Sensitive Data Used in Cloud-Based ERP Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 17–19 March 2021; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W.M.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; He, J.; Huang, G.Q. Toward Open Manufacturing: A Cross-Enterprises Knowledge and Services Exchange Framework Based on Blockchain and Edge Computing. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. 1 Blockchain’s Roles in Meeting Key Supply Chain Management Objectives. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.C.A.; Gala, C. Cloud ERP: A New Dilemma to Modern Organisations? J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2014, 54, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehle, D.; Henze, D.; Seitz, A.; Luckow, A.; Bruegge, B. PartChain: A Decentralized Traceability Application for Multi-Tier Supply Chain Networks in the Automotive Industry. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Decentralized Applications and Infrastructures (DAPPCON), Newark, CA, USA, 5–9 April 2019; pp. 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Tatge, L.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Blockchain Applications in the Supply Chain Management in German Automotive Industry. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.T.S.; Tang, Y.M.; Tsang, K.Y.; Tang, V.; Chau, K.Y. A Blockchain-Based System to Enhance Aircraft Parts Traceability and Trackability for Inventory Management. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 179, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. Blockchain Medledger: Hyperledger Fabric Enabled Drug Traceability System for Counterfeit Drugs in Pharmaceutical Industry. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 597, 120235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino, F.; Kanakaris, V.; Dasaklis, T.K.; Moschuris, S.; Stachtiaris, S.; Pagoni, M.; Rachaniotis, N.P. Blockchain-Based Food Supply Chain Traceability: A Case Study in the Dairy Sector. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 5758–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, Y.; Subramanian, N.; Dora, M.; Bhatia, M.S. Food Supply Chain in the Era of Industry 4.0: Blockchain Technology Implementation Opportunities and Impediments from the Perspective of People, Process, Performance, and Technology. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 33, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, E. Carrefour Says Blockchain Tracking Boosting Sales of Some Products. Reuters. 2019. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/business/carrefour-says-blockchain-tracking-boosting-sales-of-some-products-idUSKCN1T42C1/#:~:text=BERLIN%20(Reuters)%20%2D%20French%20retailer,an%20executive%20said%20on%20Monday (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Agrawal, T.K.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, V. Blockchain-Based Secured Traceability System for Textile and Clothing Supply Chain. In Artificial Intelligence for Fashion Industry in the Big Data Era; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; MacCarthy, B. Blockchain-Enabled Supply Chain Traceability in the Textile and Apparel Supply Chain: A Case Study of the Fiber Producer, Lenzing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstead, A.V.; Mwesiumo, D.; Moradlou, H.; Boffelli, A. Entering the World behind the Clothes That We Wear: Practical Applications of Blockchain Technology. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 35, 947–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralla, G.; Pinna, A.; Tonelli, R.; Marchesi, M.; Ibba, S. Ensuring Transparency and Traceability of Food Local Products: A Blockchain Application to a Smart Tourism Region. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenance From Shore to Plate: Tracking Tuna on the Blockchain. Available online: https://www.provenance.org/news-insights/tracking-tuna-catch-customer (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Dionysis, S.; Chesney, T.; McAuley, D. Examining the Influential Factors of Consumer Purchase Intentions for Blockchain Traceable Coffee Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 4304–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H.; Garaus, M. Using Blockchain to Signal Quality in the Food Supply Chain: The Impact on Consumer Purchase Intentions and the Moderating Effect of Brand Familiarity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shew, A.M.; Snell, H.A.; Nayga Jr, R.M.; Lacity, M.C. Consumer Valuation of Blockchain Traceability for Beef in the United States. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 44, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniyar, K.; Wu, X.; Gupta, S.; Modgil, S.; Kumar, A. Digitizing Global Supply Chains through Blockchain. Prod. Plan. Control 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jia, F.; Chen, L. Blockchain Adoption in Supply Chains: Implications for Sustainability. Prod. Plan. Control 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maersk, A.P. Moller–Maersk and IBM to Discontinue TradeLens, a Blockchain-Enabled Global Trade Platform. Available online: https://www.maersk.com/news/articles/2022/11/29/maersk-and-ibm-to-discontinue-tradelens (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Sun, Z.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J. Is Blockchain Technology Desirable? When Considering Power Structures and Consumer Preference for Blockchain. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2024, 62, 53–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, M.; Zubairi, A.; Nasser, N.; Ali, A.; Ayache, M. Ensuring Authenticity and Sustainability in Perfume Production: A Blockchain Solution for the Fragrance Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Communications (WINCOM), Istanbul, Turkey, 26–28 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Milet, K. Le Jardin Retrouvé Uses the Blockchain to Guarantee Perfume Authenticity. Available online: https://www.premiumbeautynews.com/en/le-jardin-retrouve-uses-the,20267 (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Isil, O.; Hernke, M.T. The Triple Bottom Line: A Critical Review from a Transdisciplinary Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, F. The Scent of Change: Sustainable Fragrances Through Industrial Biotechnology. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, e202300309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, K.B.M. Case Study: A Strategic Research Methodology. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2008, 5, 1602–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givenchy L’Interdit Givenchy Eau de Parfum Rouge for Woman|Givenchy Beauty. Available online: https://www.givenchybeauty.com/on/demandware.store/Sites-givenchy-beauty-us-Site/en_US/Product-Show?pid=F10100152&dwvar_F10100152_size=50ml (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Dunes Givenchy L’Interdit Givenchy Eau de Parfum Rouge. Available online: https://www.dunesmagazine.com/post/givenchy-l-interdit-eau-de-parfum-rouge (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Henry Rose Henry Rose: 100% Transparent Fine Fragrances. Available online: https://henryrose.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Paco Rabanne Phantom|Eau de Toilette|For Him|Paco Rabanne. Available online: https://www.pacorabanne.com/us/en_US/fragrance/p/phantom--000000000065158923 (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green Claims and Message Frames: How Green New Products Change Brand Attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.A.H.; MacCarthy, B.L. Blockchain Technology in the Supply Chain: Learning from Emerging Ecosystems and Industry Consortia. In Handbook on Digital Business Ecosystems; Bauman, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 367–386. ISBN 978-1-83910-719-1. [Google Scholar]

- da Cruz, A.M.R.; Cruz, E.F. Blockchain-Based Traceability Platforms as a Tool for Sustainability. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Virtual, 5–7 May 2020; pp. 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Takyar, A. Blockchain Reducing Carbon Footprints—Environmental Impact. Available online: https://www.leewayhertz.com/blockchain-reducing-carbon-footprints/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Kraft, T.; Valdés, L.; Zheng, Y. Supply Chain Visibility and Social Responsibility: Investigating Consumers’ Behaviors and Motives. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2018, 20, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef, S.; Wagner, S.M.; Saur, C. Blockchain and Network Governance: Learning from Applications in the Supply Chain Sector. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF, World Economic Forum Blockchain Toolkit. Available online: https://widgets.weforum.org/blockchain-toolkit/introduction/index.html (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Caldarelli, G.; Zardini, A.; Rossignoli, C. Blockchain Adoption in the Fashion Sustainable Supply Chain: Pragmatically Addressing Barriers. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2021, 34, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Weerakkody, V.; Ismagilova, E.; Sivarajah, U.; Irani, Z. A Framework for Analysing Blockchain Technology Adoption: Integrating Institutional, Market and Technical Factors. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, E.T.; Harman, M.; McMinn, P.; Shahbaz, M.; Yoo, S. The Oracle Problem in Software Testing: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2015, 41, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, G.; Rossignoli, C.; Zardini, A. Overcoming the Blockchain Oracle Problem in the Traceability of Non-Fungible Products. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M.D. Auditing the Blockchain Oracle Problem. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 35, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.D. ISO 9000 Quality Systems Auditing; Gower Publishing, Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-566-07900-9. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Recommendation No. 46: Enhancing Traceability and Transparency of Sustainable Value Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-64-29057-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chloé. Chloé Eau De Parfum Naturelle [Online]. Chloé. Available online: https://www.chloe.com/pt/fragrance_cod46774448gq.html (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Sephora. Chloé Signature Naturelle Eau De Parfum [Online]. Sephora. Available online: https://www.sephora.sg/products/chloe-signature-naturelle-eau-de-parfum/v/100ml (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Chloé. Nomade Eau De Parfum Naturelle [Online]. Chloé. Available online: https://www.chloe.com/pt/fragrance_cod46808891an.html (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Chloé. Atelier Des Fleurs Ylang Cananga [Online]. Chloé. Available online: https://www.chloe.com/pt/fragrance_cod46774451lk.html (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Police. Police To Be Green EDT VAPO [Online]. Police. Available online: https://policelifestyle.com/ww-en/police-to-be-green-edt-vapo-tobegreen-p?variant=1451242 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Stylemate, T. Phantom the new fragrance by Paco Rabanne [Online]. THE Stylemate. 2021. Available online: https://www.thestylemate.com/phantom-the-new-fragrance-by-paco-rabanne/?lang=en (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Ulta. Ariana Grande God Is A Woman Eau de Parfum [Online]. Ulta Beauty. Available online: https://www.ulta.com/p/god-a-woman-eau-de-parfum-pimprod2026595 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Amazon. Downy Premium Parfum Adorable Bouquet Concentrate Fabric Conditioner, 1.4L [Online]. Amazon. Available online: https://www.amazon.sg/Downy-Premium-Adorable-Concentrate-Conditioner/dp/B08CP7D9KP/ref=pd_sim_sccl_3_4/358-6844246-8714606?pd_rd_w=LDyob&content-id=amzn1.sym.bab7a3b2-fe0e-4730-a8fb-98e53a0356f3&pf_rd_p=bab7a3b2-fe0e-4730-a8fb-98e53a0356f3&pf_rd_r=QTZC39ERXD1TZ09X6EN2&pd_rd_wg=vcgrs&pd_rd_r=ec5175c4-52ae-44b5-a2b2-d8b0c418a1fb&pd_rd_i=B08CP7D9KP&psc=1 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Market, G. Hygiene Expert Care Life Nature Concentrate Fabric Softener Sunrise Kiss 1150ML [Online]. Gourmet Market. 2022. Available online: https://gourmetmarketthailand.com/en/hygiene_expert_care_life_nature_concentrate_fabric_softener_sunrise_kiss_1300ml_88161341083937 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Amazon. Skip Essence de la Nature Ecological Liquid Laundry Detergent (2 x 36 Washes) [Online]. Amazon. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Skip-Essence-Ecological-Laundry-Detergent/dp/B082VVGVT3 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Original Source. Our Products [Online]. Original Source. Available online: https://www.originalsource.co.uk/products/originals/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Goisco. Downy Nature Fabric Softener, Pomegranate & Vanilla Scent, 2.65 L [Online]. Goisco. Available online: https://goisco.com/en-bq/products/downy-nature-fabric-softener-pomegranate-vanilla-scent-2-65-l (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- HSDS. Downy Nature Pomegranate Flower and Vanille Fabric Softener [Online]. HSDS Online. Available online: https://www.hsdsonline.com/nl/product/downy-nature-pomegranate-flower-and-vanille-fabric-softener-variety/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- D’Orange, E.L. Les Fleurs du Déchet – I am Trash [Online]. Etat Libre d’Orange. Available online: https://www.etatlibredorange.com/products/les-fleurs-du-dechet-i-am-trash (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Rose, S. Vigilante [Online]. ST. Rose. 2022. Available online: https://www.st-rose.com/products/vigilante-eau-de-parfum (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Floratropia. Our Engagements [Online]. Floratropia Paris. Available online: https://floratropia.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Rochas. Girl [Online]. Rochas. Available online: https://www.rochas.com/en/new/girl-the-new-fragrance (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Ulta. Polo Earth Eau de Toilette [Online]. Ulta Beauty. Available online: https://www.ulta.com/p/polo-earth-eau-de-toilette-pimprod2032537 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Love Beauty and Planet. Collections [Online]. Love beauty and planet. Available online: https://www.lovebeautyandplanet.com/us/en/collections.html (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Love Beauty and Planet. Our fragrances [Online]. LOVE home and planet. Available online: https://www.lovehomeandplanet.com/us/en/fragrances.html (accessed on 15 July 2024).

| Claim Category | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Origin/Provenance (O) | Guaranteeing a specific geographical origin, country, city/urban area, region or location for the product’s source or any constituent element’s source, e.g., vanilla from Madagascar. |

| Authenticity (A) 1 | Assurance that the product has been produced (and distributed) by the labelled brand/manufacturer/vendor/retailer, e.g., a genuine branded product from Brand X. |

| Material (M) | The product contains a specific ingredient or a proportion of a specific ingredient within it, e.g., contains natural vanilla. |

| Quality (Q) | The properties or the ingredient(s) in the product or the properties of the product meet specific quality standards or have specific quality attributes, e.g., 100% natural perfume. |

| Upcycling (U) | Use of another industry’s waste to generate valuable fragrance ingredients used in the product, e.g., upcycled cedarwood atlas. |

| Processing (P) | The product or its ingredient(s) have been produced or manufactured in a specific way, e.g., alcohol distilled from natural beets. |

| Classified or Certified (C) | The product falls into a defined category of product or is certified, accredited, verified by another agency, e.g., certified vegan product. |

| Traceable (T) | Assurance that the origin of the product can be identified and checked, e.g., a specific natural ingredient is traceable. |

| Environmental Sustainability (SE) | A specific claim that the product or its ingredient(s) or manufacturing and production methods are sustainable environmentally, e.g., minimal impact on the environment. |

| Social/Ethical Sustainability (SS) | A specific claim that the product or its ingredient(s) or manufacturing and production methods generate social benefits or meet ethical standards, e.g., ensuring good working conditions. |

| Economic Sustainability (SM) | A specific claim that the product or its ingredient(s) or manufacturing and production methods generate economic benefits for those involved in the supply chain or the region from which it comes, e.g., creating local employment. |

| Interviewee | Current Role | Previous Industries | Total Years of Work Experience | Knowledge on RM Fragrance Sourcing and Traceability Challenges | Mode of 1st Interview and Length | Mode of Follow-Up Interview(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee 1 | Head of R&D. Role: The development of raw materials and RM/ingredient sourcing for the FMCG and cosmetics industries. | Fragrance and FMCG | 32 years | Currently working in the raw materials industry, supporting customers with provenance, sustainability and ethical claims. | Face to face for 1 h | Face to face + online |

| Interviewee 2 | Head of quality assurance. Role: Quality assurance of fragrances, raw materials and suppliers. | Fragrance and beverages | 33 years | Actively involved in sourcing, quality control and quality assurance of fragrance Raw Materials. | Face to face for 1 h | Face to face + online |

| Interviewee 3 | Regional marketing manager. Role: Marketing fragrance solutions to customers in the region. | FMCG and Fragrance | 11 years | Promoting the importance of sustainability, ethical sourcing, and provenance assurance to customers. | Online for 45 min | Online |

| Interviewee 4 | Regional R&D director Role: Fragrance R&D and raw material sourcing. | Fragrance and FMCG | 26 years | Strong knowledge on fragrance RMs and associated sourcing, as well as traceability and sustainability. Set up raw materials crisis team to ensure sustained supply when faced with crisis situations. | Online for 1 h | Online |

| Interviewee 5 | Senior manager Role: Consumer and product research. | Skin care and cosmetics | 11 years | Actively involved in ensuring sustainability, ethical and provenance claims of FMCG and cosmetics products. | Face to face for 1 h | Face to face |

| CLAIM | O | M | Q | U | P | C | T | SE | SS | SM | STOT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfumes and fine fragrances 14 | 19 | 45 | 13 | 11 | 16 | 14 | 4 | 14 | 12 | 3 | 40 | Total ingredient claims | 58 |

| Average claims per product 4.2 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2.9 | Average claims per ingredient | 2.6 |

| Household products and consumer goods 9 | 23 | 34 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | Total ingredient claims | 36 |

| Average claims per product 4.0 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.9 | Average claims per ingredient | 2.2 |

| Overall 23 | 42 | 79 | 19 | 11 | 21 | 16 | 4 | 19 | 15 | 3 | 48 | Total ingredient claims | 94 |

| Average claims per product 4.1 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 2.1 | Average claims per ingredient | 2.4 |

| Topic | Summary of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Importance of traceability, transparency, provenance, ethical sourcing, authenticity and sustainability |

|

| Topic | Summary of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Major traceability and transparency challenges in the fragrance industry |

|

| Potential usefulness of blockchain technology in the industry’s supply chain |

|

| Weaknesses of the fragrance supply chain that can be improved by blockchain technology |

|

| Greatest potential strengths of blockchain technology |

|

| Topic | Summary of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Customer and end-consumers’ trust in blockchain-enabled transparency and traceability |

|

| Topic | Summary of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Type of blockchain suitable for the fragrance industry |

|

| Blockchain as an addition to existing systems or a major disruption |

|

| Topic | Summary of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Challenges and obstacles to implement blockchain technology |

|

| Negative effects of blockchain technology |

|

| Collaboration opportunity or conflict with regulatory and legal authorities or systems |

|

| Awareness of specific initiatives in this area |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

MacCarthy, B.L.; Das, S.; Ahmed, W.A.H. Smell the Perfume: Can Blockchain Guarantee the Provenance of Key Product Ingredients in the Fragrance Industry? Sustainability 2024, 16, 6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146217

MacCarthy BL, Das S, Ahmed WAH. Smell the Perfume: Can Blockchain Guarantee the Provenance of Key Product Ingredients in the Fragrance Industry? Sustainability. 2024; 16(14):6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146217

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacCarthy, Bart L., Surajit Das, and Wafaa A. H. Ahmed. 2024. "Smell the Perfume: Can Blockchain Guarantee the Provenance of Key Product Ingredients in the Fragrance Industry?" Sustainability 16, no. 14: 6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146217

APA StyleMacCarthy, B. L., Das, S., & Ahmed, W. A. H. (2024). Smell the Perfume: Can Blockchain Guarantee the Provenance of Key Product Ingredients in the Fragrance Industry? Sustainability, 16(14), 6217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146217

_Lu.png)