Abstract

Green concrete is a concept of concrete that uses waste materials to reduce its environmental impact and has various benefits for the environment, economy, and society, such as lower construction cost, less landfill waste, new waste markets, and better quality of life. This study aims to investigate and analyze the barriers and enablers for green concrete development and implementation, based on a mixed-method approach that combines a scientometric analysis and a literature review. The Scopus database was explored first and then these data were used to investigate and capture six categories of barriers and enablers: awareness, technical, economic and market, implementation, support/promotion, and social. Results reveal that the technical and operational aspects are the main challenges for green concrete, while the awareness and social acceptance are not major issues. The current study surpasses the mere popularization of green concrete. Instead, it delves into its multifaceted dimensions, that is, technical, economic, social, and institutional. By meticulously analyzing a diverse group of research articles, key challenges and opportunities associated with green concrete are pinpointed. The findings not only deepen our understanding of the barriers impeding the widespread adoption of green concrete, but also shed light on potential solutions. In summary, this work bridges theory and practice, providing invaluable insights for future researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in the sustainable construction domain.

1. Introduction

Concrete is one of the most widely used construction materials globally [1,2,3], but it also has a significant environmental impact due to its high consumption of natural resources, energy-intensive production process, and large carbon footprint [4,5,6,7,8]. To address these issues, a new concept of concrete has emerged, called green concrete, which aims to minimize the environmental impact of concrete by using waste materials as partial replacements for cement or aggregates [9,10,11], enhancing the durability and performance of concrete and improving the sustainability of the concrete life cycle [12,13,14]. In the pursuit of a sustainable future, the construction industry has turned its focus toward green concrete, a material that not only promises environmental benefits, but also encompasses a complex paradigm involving many parameters. Green concrete is defined not just by its composition, which substitutes traditional cement with ecofriendly industrial waste materials like fly ash, blast slag, and silica fume, but also by its application and the broader implications for sustainability [15,16,17,18].

The discussion on green concrete is comprehensive, considering its global relevance and the various parameters that lead to its classification as ‘green’. These parameters include, but are not limited to, the use of recycled materials, reduction of carbon footprint, and energy efficiency in production. The field of application for green concrete is diverse, extending to roadworks, pavements, buildings, and more, each with its unique requirements and challenges [19,20,21].

By establishing this framework, this paper aims to provide a thorough understanding of green concrete, reflecting on its multifaceted nature and the collective efforts required to integrate it into mainstream construction practices worldwide. It is a concept of concrete that aims to meet a holistic approach of sustainability, balancing economic, social, and environmental benefits. It is not only beneficial for the environment, but also for the economy and society, as it can reduce the cost of construction, save landfill space, create new markets for waste materials, and greatly improve the quality of life for the users of concrete structures [22,23,24,25,26].

However, green concrete also faces many challenges and barriers that prevent its widespread adoption and application in the construction industry [18,19]. These include technical, economic, social, and institutional factors, such as the lack of standards and specifications, the uncertainty of material properties and performance, the higher initial cost and risk, the low awareness and acceptance, and the inadequate policies, guidelines, and incentives [27,28,29,30]. The context of green concrete development and implementation is not well-studied, limiting its potential and acceptance. Therefore, the main question here is why the construction industry has not fully embraced the concept of green concrete. To capture the state of the art of green concrete, it is essential to analyze the latest developments, difficulties, and prospects in this area. A comprehensive and systematic analysis of the factors that militate against green concrete development and implementation is strongly needed, considering the views and insights of the key practitioners and specialists in the concrete industry. The discovery of such factors will allow for policy decision makers to be better informed as to how they can develop strategies and guidelines that will increase the use of green concrete to meet the massive demand of urbanization.

2. Methodology

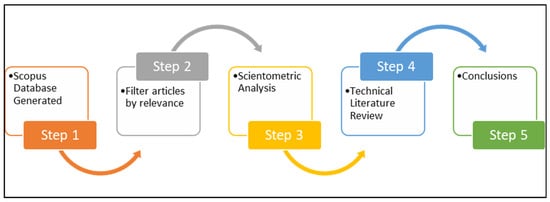

There are many barriers and enablers that contribute significantly to the implementation of green concrete. For example, some recent studies have highlighted the potential of green concrete and the challenges its implementation faces. Innovations like using polluted sediment for ultra-lightweight concrete show promise in recycling and performance, but face adoption barriers such as the need for industry standards [18]. Research into quaternary blended cement points to significant CO2 reductions, yet further differentiation of green concrete approaches is needed to fully harness their advantages. These insights highlight the importance of targeted research to navigate the complexities of green concrete implementation [17]. Therefore, this study aims to conduct a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the barriers and enablers for green concrete adoption and implementation, based on the perspectives and experiences of the relevant researchers, stakeholders, and experts in the concrete industry. To develop a consistent foundation for addressing green concrete implementation, the current study adopts a mixed-method approach: a scientometric analysis followed by a comprehensive technical literature review. A systematic investigation of existing publications can assist researchers in capturing the current body of knowledge and stimulate inspiration for upcoming research work. The current research used the Scopus database as the main source of data for both methods. It applied the following steps to conduct the research as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Research methodology scheme.

Step 1: Search and filter the documents related to the research topic on the Scopus database using a specific query.

Step 2: Perform the scientometric analysis on the selected documents using the R package to generate various statistics and visualizations, such as the main information, annual scientific production, and most relevant sources.

Step 3: Perform the literature review on the selected documents using a thematic analysis approach to identify and classify the barriers and enablers for green concrete into six categories: awareness, technical, economic and market, implementation, support/promotion, and social.

2.1. Scientometric Analysis

To conduct the scientometric analysis, an intense search was done on the Scopus database using the following query: “(ABSTRACT (barrier) OR (enabler)) AND ((ABSTRACT (green AND concrete)))”. This query returned 91 documents, which were then filtered by relevance to the topic of green concrete. With these documents, the biblioshiny under the bibliometrix library of the R package [31] was used to perform the scientometric analysis, which is as follows.

Main Information

Table 1 shows the main information about the data used for the analysis. Spanning from 1977 to 2024, the green concrete research dataset comprised 91 documents from 80 distinct sources, reflecting a steady growth in the field with an annual publication rate of 3.48%. The average citation count of 18.24 per document, alongside a total of 3467 references, underscores the significant academic impact of these works. The collaboration is evident with 292 authors, 26.37% of whom have engaged in international co-authorships, highlighting the global commitment to sustainable construction practices. The diversity of document types, including articles, conference papers, and reviews, reveals a dynamic discourse and peer-reviewed insights that are shaping the evolution of green concrete research. This dataset not only charts the historical and current landscape, but also projects a future of continued scholarly exchange and innovation in the pursuit of environmental sustainability in the construction industry. This shows the different formats and venues of the documents, as well as the different stages and purposes of the research.

Table 1.

Main information.

2.2. Annual Scientific Production

Table 2 shows the annual scientific production of the documents which reflects the scholarly output on green concrete research from 1977 to 2024. It begins with a solitary article in 1977, followed by a period of minimal activity. A significant increase in publications is observed from 2013, culminating in a peak of 13 articles in 2023, indicative of heightened research interest and activity in recent years. In 2024, the count stands at five articles thus far. This trend suggests an increasing recognition of the importance of green concrete technology in sustainable construction, likely driven by growing environmental concerns and the industry’s push toward ecofriendly materials. The data indicate an emerging field that is rapidly gaining traction, as it tackles critical challenges within the construction industry context. Moreover, there is a discernible trend toward increased academic and practical contributions.

Table 2.

Annual scientific production.

2.3. Most Frequent Words

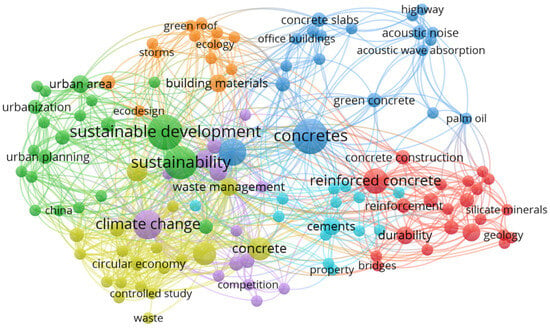

Figure 2 provides an overview of the frequency of keywords related to sustainable construction and environmental impact of green concrete. The most frequently mentioned term was “concretes”, appearing the most, underscoring the focus on construction materials. The phrase “sustainable development” followed closely after “concretes”, highlighting the importance of sustainability in the construction industry. Other significant terms included “climate change”, “environmental impact”, and “recycling”, indicating a strong emphasis on ecological considerations. Additionally, terms like “reinforced concrete”, “waste management”, and “urban area” appeared multiple times, reflecting the diverse aspects of sustainability and environmental management within the context of urban development and construction practices. This suggests a detailed exploration of how building materials like concrete can be optimized to achieve the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) of sustainability and how the construction industry can adapt to reduce its environmental footprint while developing their economy.

Figure 2.

Keyword frequency distribution in green concrete research literature.

3. Results and Discussions

This study revealed the main barriers and enablers for the adoption of green technologies in concrete production, a major construction material with a high environmental impact. By identifying, investigating, and reviewing the relevant articles from different sources, the study classified the barriers and enablers into six categories: awareness, technical, economic and market, implementation, support/promotion, and social. The frequency analysis showed that the most frequent barriers were technical and implementational, while the most frequent enablers were technical and support/promotion. The study concluded that a comprehensive understanding of the barriers and enablers is essential for the success of the adoption of green technologies in concrete production and suggested some directions for future research.

3.1. Barriers and Their Analysis

Table 3 categorizes the barriers mapped against their description along with key references. The barriers were clustered under categories namely: awareness, technical, economic, implementation, support/promotion, and social respectively.

Table 3.

Green concrete barriers along with their description.

3.1.1. Barrier’s Explanation

Awareness:

The awareness category refers to the lack of knowledge, education, awareness, or benefits of various green solutions among different stakeholders and decision-makers. One of the barriers in this category is the lack of knowledge and education about the benefits and potential of recycled materials for building construction which may lead to misconceptions or negative perceptions by various stakeholders such as road agencies, contractors, subcontractors, and the public [32,33]. Another barrier is the lack of awareness, knowledge, and benefits of nature-based solutions, which are often overlooked or underestimated compared to grey solutions by stakeholders and decision-makers. They may also have doubts about their efficiency, effectiveness, and reliability [34]. Similarly, many companies are unaware of the benefits of the green competitive advantage or lack the necessary knowledge and practical skills to fully adopt green innovation and environmental management practices [35,36,37]. Moreover, many managers and employees are not fully aware of the potential benefits that green and digital factors can bring to their firms, such as improved efficiency, innovation, and competitiveness [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. A final barrier in this category is the resistance to change that some stakeholders may have toward standardization and design for disassembly which they may perceive as a threat to their project uniqueness and architectural freedom. They may also lack the required knowledge and skills to implement these principles [47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

Technical:

The technical category includes barriers related to the availability, efficiency, quality, and performance of green technologies and materials. For example, the cement industry faces challenges in finding and using alternative energy sources and improving fuel efficiency in the existing plants [54,55,56,57]. The use of recycled materials in building construction and the monitoring of nature-based solutions lack specifications and standards which can help in promoting best practices [32,33]. The precast concrete industry suffers from physical damage and waste due to inappropriate battens, unclear identification marks, large inventory, and lack of sufficient care [2,59,60,61,62,63]. The existing buildings have limitations in installing and operating new green technologies due to the building age, condition, space, automation systems, and metering systems [64,65,66,67]. The lightweight concrete structures have reduced mechanical properties compared to normal weight concrete [68,69,70]. The reuse of components and design for disassembly require skills, facilities, and technology that are not widely available or feasible [47,50,52,71,72].

Economic and Market:

This section discusses various economic and market barriers that hinder the adoption and implementation of green solutions in different sectors. Some of these barriers are: (i) the British Columbia carbon tax, which increases the compliance costs and reduces the competitiveness of the British Columbia cement industry [54,57,74], (ii) the cost and availability of materials which may make recycled materials less attractive than conventional materials [32], (iii) the cost of renewable energy which is much higher than that of coal, the dominant fossil fuel used in cement manufacturing, (iv) the high costs and uncertain returns of investing in green and digital factors, such as technological innovation and environmental management [64,75], (v) the lack of funding and incentives for nature-based solution implementation and monitoring which may limit the financial feasibility and attractiveness of these projects [34], (vi) the lack of government grants and incentives which may discourage building owners from investing in green measures [64,75], (vii) the lack of government support, which may create policy uncertainty and inconsistency for firms pursuing the green competitive advantage [64], (viii) the lack of support and incentives which may generate resistance or opposition from internal or external stakeholders who do not share the same vision or values of the green competitive advantage, and (ix) the perceived split benefits, which create an imbalance between the costs accepted by the building owners and the benefits appreciated by the tenants [38,47,68,69,70,72,73].

Implementation:

This section discusses various barriers that hinder the adoption or implementation of different green solutions in various sectors, such as cement, road, building construction, and nature-based solutions. The implementation category includes the barriers that affect the execution and operation of the green solutions. Some examples of these barriers are: (i) cement standards that limit the potential contribution from limestone substitution [54,74], (ii) equipment and operational issues that arise from the use of recycled materials in construction projects [32], (iii) inappropriate staffing arrangements and unclear working instructions for the lifting and handling of precast concrete products [59,60], (iv) lack of periodic stock checks that affect the delivery and production planning [59,63], (v) tenant and staff education, behaviors, and priorities that largely influence the energy consumption and conservation in buildings [64,66], (vi) leasing agreements that restrict or conflict with the green operation goals [64], (vii) lack of coordination and integration of nature-based solutions across sectors and scales [34], (viii) clients and end-users resistance and uncertainties due to the durability and ductility issues of lightweight concrete [68,70], (ix) lack of a legal framework that prevents the safe and responsible reuse of components [47,51,53], (x) lack of strategic alignment, integration, and collaboration among the various practitioners and stakeholders in the green supply chain, and (xi) lack of a clear and coherent strategy and coordination for pursuing twin transitions [35,37].

Support/promotion:

The support/promotion category includes various barriers that affect the adoption and implementation of green solutions in different sectors. For example, the British Columbia cement industry lacks specific measures from the provincial government to support its greenhouse gas reduction strategy [54,74]. The use of recycled materials in various construction activities faces insufficient financial, regulatory, or institutional incentives or policies to encourage its adoption and implementation [32]. The property owners need to be informed and persuaded about the long-term advantages of green operation, such as lower operating costs, higher market value, and improved corporate image which will contribute to brand recognitions [64,66,67]. Nature-based solutions projects may not have an effective communication and dissemination strategies to share their results and best practices with relevant audiences, such as policymakers, practitioners, researchers, or the general public [34]. Some companies may not receive sufficient support or guidance from the government to implement the green competitive advantage or twin transitions, such as clear and consistent policies, regulations, standards and guidelines, or law enforcement [35,36,38,78].

Social:

The social category includes various barriers that affect the adoption and implementation of green solutions in different sectors. One of the barriers is consumer preferences, which determine the demand for cement and cement products. The industry needs to communicate the sustainability benefits of using green concrete products to the consumers and other stakeholders [54,55]. Another barrier is the environmental and social impacts of using recycled materials, which may have positive or negative effects on the environment and society, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, saving landfill space, or affecting road safety and aesthetics [32]. A third barrier is the lack of top management commitment to implement environmental management practices, something which can hinder the adoption of green stock management [59,61]. A related barrier is the lack of employee involvement and training in green stock management, a phenomenon which can reduce the awareness and motivation of the workers [59]. A fifth barrier is the occupational health and safety risks associated with the installation or operation of new green measures which may affect the safety and well-being of the building users [64,66,67]. A sixth barrier is the building compliance issue which requires the adherence to the existing building codes and standards which may not always be compatible with some green measures [64]. A seventh barrier is the architectural and aesthetic implications of new green measures which may greatly impact the appearance and ambience of the building, affecting the satisfaction and preference of the building users [64,67]. An eighth barrier is the lack of proactive stakeholder engagement and participation in nature-based solutions design and monitoring which may affect their acceptance, ownership, and sustainability. Stakeholders will always have different preferences, values, and expectations of nature-based solutions which may need to be addressed and balanced in a proactive and iterative process [34]. A ninth barrier is the lack of social responsibility, trust, and awareness among some companies, which may prioritize short-term profits over long-term sustainability and ignore the needs and expectations of their stakeholders and society at large [79,80]. They may also lack the trust and legitimacy to engage in the green competitive advantage [35,36]. A tenth barrier is the social barriers in adopting and implementing green and digital factors, such as negative perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of customers, employees, and society. They also face ethical and legal issues, such as privacy, security, and accountability [38,73,78].

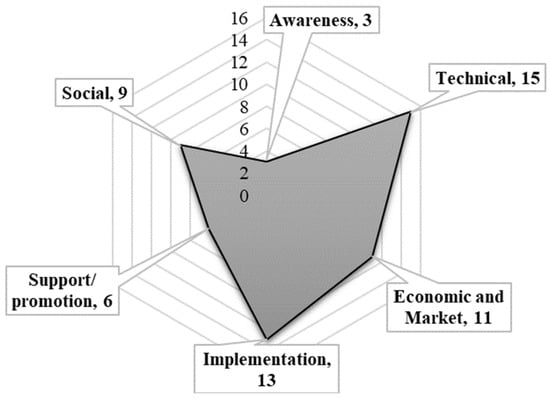

3.1.2. Barrier Frequency Analysis

Table 4 shows the frequency of different categories of barriers relative to the adoption of green technologies in concrete production, based on a review of 57 research papers. The categories were awareness, technical, economic and market, implementation, support/promotion, and social. Figure 3 displays a radar diagram to visualize the data. The most frequent category of barriers was found to be technical, with 15 indicators, followed by implementation, with 13 barriers. The least frequent category was awareness, with only three factors. The other categories have moderate frequencies, ranging from six to 11 indicators. Table 5 and Figure 3 suggest that the main challenges for green technologies in concrete production are related to the technical and operational aspects of the technologies, rather than the awareness or social acceptance of them.

Table 4.

Frequencies of different categories of barriers.

Figure 3.

Category representation of barriers frequency.

Table 5.

Green concrete enablers along with their description.

3.2. Enablers and Their Analysis

3.2.1. Enabler’s Explanation

Awareness:

One of the categories of enablers is awareness, which refers to the level of environmental awareness and knowledge among the practitioners involved in the construction sector. Some examples of enablers in this category are: (i) key practitioners, advocates, and champions who initiate, mainstream, and sustain momentum for climate adaptation by raising awareness and mobilizing resources [54,57,74,81], (ii) science-based engineering methods that use advanced mechanistic laboratory tests and structural asset management techniques to quantify the benefits of recycled material systems and validate their end-product performance [32,33], (iii) environmental awareness among precasters and their stakeholders of the environmental issues and benefits of green supply chain management [59,61], (iv) circular economy, a concept that aims to reduce the environmental impact of production and consumption by minimizing resource extraction, waste generation and emissions, and maximizing the value retention of products and materials through reuse, recycling, and recovery [47,49,51,53], (v) green human resource management, a set of practices that aim to promote and support employees’ green behavior and environmental awareness [38,40,42,43], and (vi) green innovation, the development of products, services, or processes that reduce environmental impacts and create value for customers and society [35,37].

Technical:

This section identifies technology development as one of the enablers of green construction. It involves research and development activities to explore less CO2-intensive cementing materials and manufacturing processes and adopt proven CO2 control technologies and practices [54,55]. Some examples of technology development include the impact crusher [32], site layout design [59,61,63], substantial decrease in density and in building element self-weight [68,82,83], internet of things [38], technological innovation [38,40], design for disassembly, standardization and specific guidelines and strategies [47,72,84,85,86,87], and environmental management and effective waste management protocol [35]. For instance, the impact crusher is a device that can process rubble materials into high-quality structural base course and substructure drainage aggregates with minimal waste and improved mechanical properties. Similarly, design for disassembly is an approach to the design of a product or constructed asset that facilitates disassembly at the end of its useful life in such a way that it enables components and parts to be reused, recycled, recovered for energy or, in some other way, diverted from the waste stream.

Economic and Market:

The economic and market category of enablers covers the aspects that influence the financial performance and market position of the construction sector, as well as the demand and supply of green products and services. Some examples of enablers in this category include (i) market demand, which drives the cement industry to maintain and increase its market share by investing in low-carbon solutions [54,57], (ii) reduced aggregate haul, which lowers the transportation costs and energy consumption by using local and recycled materials [32], (iii) incentive schemes, which reward precasters for adopting green supply chain management practices [59,63], (iv) cost savings of concrete elements which are achieved by using local waste scoria as a cheaper and greener alternative to limestone aggregate [68,85], (v) investment in environmental management which involves allocating resources and efforts toward environmentally friendly behaviors and strategies [38], and (vi) green intangible assets, which are the non-physical resources of a firm that give it a green competitive advantage, such as green reputation, green knowledge, green culture, and green capabilities [35,36].

Implementation:

The implementation category of enablers of green construction consists of several factors that facilitate the execution and delivery of green construction projects. One of these factors is multilevel institutional coordination, which entails the coordination between different political and administrative levels in society to ensure effective and coherent implementation of climate adaptation measures [54]. Another factor is the use of conventional road construction equipment to place and compact recycled materials in road structures, without requiring special modifications or adaptations [32]. A third factor is the stock control system that helps precasters monitor and manage their inventory levels and reduce waste [59,63]. A fourth factor is the structural flexibility that allows the engineers to design smaller structural elements and greater span to depth ratio using lightweight concrete [68,81,83]. A fifth factor is the green work climate perception, which is the employees’ perception of the extent to which the company supports and encourages green behavior and sustainability [38]. A sixth factor is the green organizational identity, which is the extent to which a firm perceives itself as being environmentally responsible and committed to green values and goals [35,36].

Support/promotion:

The support/promotion category in the table includes various enablers that can facilitate or encourage the adoption of green and sustainable practices in the construction sector. Some of the enablers are (i) policy support from the government which can help the industry cope with the carbon tax and access alternative and renewable energy sources, supplementary cementing materials, and new technologies [54], (ii) green street program, which is a collaborative initiative between the City of Saskatoon and the University of Saskatchewan to investigate and demonstrate the use of recycled materials in urban road rehabilitation projects [32], (iii) green labelling scheme, which is the scheme that certifies and promotes the products with low environmental impact [59,63], (iv) investment in environmental management, consisting of the allocation of resources and efforts toward environmentally friendly behaviors and strategies [38], and (v) stakeholder cooperation, which is the collaboration and communication among different practitioners in the construction sector, such as designers, contractors, manufacturers, clients, governments, knowledge institutions and federations, to create and support the necessary construction standards for component reuse [47,72].

Social:

The social category of enablers of green construction includes factors that relate to the human and social aspects of the industry and the society. Some of the enablers in this category are industry collaboration [54,56], environmental stewardship [32], employee involvement [59,63], improved thermal insulation and sound absorption [68,83], green work climate perception [38], and green human capital [35,37]. Industry collaboration involves the collaboration with the global counterparts and other stakeholders of the cement industry to advance its climate action strategy and share best practices. Environmental stewardship refers to the use of recycled materials, reducing the landfilling of waste materials, conserving natural resources, and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions associated with various construction activities. Employee involvement means the involvement of employees in the decision-making and implementation of GSCM practices. Improved thermal insulation and sound absorption enhances the comfort and quality of the buildings using lightweight concrete, as they can reduce heat loss and noise pollution. Green work climate perception can help companies enhance their green culture, increase their employees’ satisfaction and commitment, and strengthen their green reputation and image, achieving intangible values. Green human capital is the knowledge, skills, and abilities of employees that enable them to perform green tasks and activities effectively and efficiently.

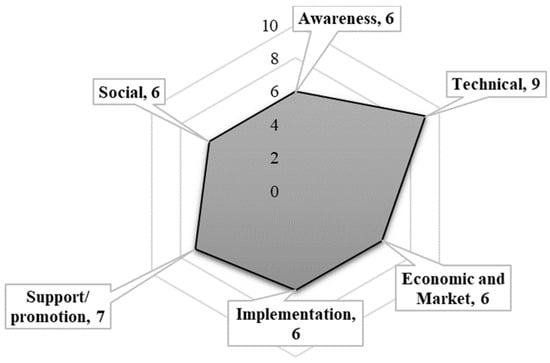

3.2.2. Enabler Frequency Analysis

This section analyses the enablers for the adoption of green technologies in concrete production, including factors that facilitate or hinder the implementation of such initiatives. The enablers are classified into six categories: awareness, technical, economic and market, implementation, support/promotion, and social. Table 6 and the radar diagram shown in Figure 4 illustrate the frequency of each category of enablers, based on a review. The results show that technical enablers were the most common, with nine occurrences, followed by support/promotion enablers, with seven occurrences. The other four categories had the same frequency, with six occurrences each, indicating that they are equally important for green technologies in concrete production. It concludes that a comprehensive understanding of the enablers is essential for the success of the adoption of green technologies in concrete.

Table 6.

Frequencies of different categories of enablers.

Figure 4.

Category representation of enablers frequency.

4. Conclusions

The current research paper adopted a holistic methodology to identify and analyze barriers and enablers for green concrete implementation. This research developed its own model to capture relevant factors which may be helpful for upcoming research as a theoretical foundation. This research could support all stakeholders, including practitioners, policymakers, and researchers in the field of “architecture, engineering, construction and operations” (AECO) who may benefit from the findings of this research by gaining an in-depth understanding of the barriers and enablers of green concrete implementation buildings and construction industry. The limitations and the possible research directions may serve as guidelines for streamlining the practical adoption and implementation of green concrete for buildings by the construction industry. The conclusions that were drawn from this study are:

- As a theoretical contribution to the body of knowledge, this study summarizes the main barriers and enablers related to green concrete implementation in the extant literature, providing insights into the nexus of green concrete and the building sector for subsequent empirical development.

- Six categories of factors are identified that affect green concrete implementation: awareness, technical, economic and market, implementation, support/promotion, and social as:

- ○

- Technical challenges: the study identifies technical issues as the primary obstacles to the development and implementation of green concrete. These include the availability of alternative energy sources, the efficiency of existing plants, and the lack of clear standards for recycled materials.

- ○

- Economic and market barriers: economic factors, such as the British Columbia carbon tax, affect the competitiveness of the cement industry. The cost of renewable energy and recycled materials also presents a challenge, alongside the lack of government grants and incentives.

- ○

- Implementation hurdles: the adoption of green concrete is hindered by implementation barriers such as restrictive cement standards, equipment and operational issues, and the need for appropriate staffing arrangements.

- ○

- Support and promotion: the study highlights a lack of policy support and incentives for the use of recycled materials in construction, something which is crucial for the promotion of green concrete.

- ○

- Social acceptance: consumer preferences and the environmental and social impacts of using recycled materials are social factors that influence the adoption of green concrete.

- It reveals that technical and operational aspects are the main barriers, while awareness and social acceptance are not major issues.

- Highlights the need for more research and innovation to overcome the technical and operational barriers and promote the adoption of green concrete.

- The study concludes that overcoming these barriers requires a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and a collaborative effort from all stakeholders involved in the construction industry. Future research directions include developing clear guidelines, improving technical standards, and fostering greater awareness and education about the benefits of green concrete.

- The study also concludes that green concrete is a promising solution for the sustainable development of the construction industry, but it requires more collaboration and coordination among the stakeholders and experts.

Based on the analysis, future research may focus on identifying and modelling significant barriers to green concrete adoption within the context of the construction sector worldwide by using the interpretive structural modelling technique. This technique is a multi-criteria decision-making methodology which is always applied to identify interrelationships among various barriers and highlight the main barriers that hamper effective implementation and adoption of green concrete.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some potential limitations and future directions are as follows:

- Geographical limitations: the research findings may be influenced by regional factors, and, thus, may not be universally applicable. The study is primarily relevant to the regions and countries represented in the dataset.

- Methodological constraints: the mixed-method approach, combining a scientometric analysis and a literature review, may have inherent limitations in capturing the nuanced perspectives of practitioners and experts in the field.

- Subjectivity in classification: the classification of barriers and enablers into six categories may introduce subjectivity, as certain factors could overlap or fit into multiple categories.

- Quantitative analysis: the current study focuses on quantitative analysis and might overlook the qualitative aspects of green concrete adoption, such as stakeholder perceptions and experiences.

- Economic and market dynamics: the current research may not fully capture the complex economic and market dynamics that influence the adoption of green concrete, such as policy changes or shifts in industry practices.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Naik, T.R. Sustainability of Concrete Construction. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2008, 13, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. The Greening of the Concrete Industry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïtcin, P.-C. Cements of Yesterday and Today. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebani, B.; Said, A.; Memari, A. Less Carbon Producing Sustainable Concrete from Environmental and Performance Perspectives: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A. Recent Advances in the Concrete Industry to Reduce Its Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Environ. Chall. 2020, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulčić, H.; Cabezas, H.; Vujanović, M.; Duić, N. Environmental Assessment of Different Cement Manufacturing Processes Based on Emergy and Ecological Footprint Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 130, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Sarker, P.K.; Biswas, W.K. Effect of Fly Ash on the Service Life, Carbon Footprint and Embodied Energy of High Strength Concrete in the Marine Environment. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.S.; Shariq, M.; Mohammad, Z.; Akhtar, S.; Masood, A. Effect of Elevated Temperature on the Structural Performance of Reinforced High Volume Fly Ash Concrete. Structures 2023, 57, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. The Role of Inorganic Polymer Technology in the Development of ‘Green Concrete’. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.H.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Yap, S.P.; Lee, S.C. Green Concrete Partially Comprised of Farming Waste Residues: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 117, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbabi, M.S.; Carrigan, C.; McKenna, S. Trends and Developments in Green Cement and Concrete Technology. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaidi, S.M.A.; Dinkha, Y.Z.; Haido, J.H.; Ali, M.H.; Tayeh, B.A. Engineering Properties of Sustainable Green Concrete Incorporating Eco-Friendly Aggregate of Crumb Rubber: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, M.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Minocha, A.K.; Deoliya, R.; Maiti, S. Recycled Aggregate from C&D Waste & Its Use in Concrete—A Breakthrough towards Sustainability in Construction Sector: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.M.; Ansari, S.S.; Hasan, S.D. Towards White Box Modeling of Compressive Strength of Sustainable Ternary Cement Concrete Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 149, 110997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Murali, G.; Khalid, N.H.A.; Fediuk, R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Lee, Y.H.; Haruna, S.; Lee, Y.Y. Slag Uses in Making an Ecofriendly and Sustainable Concrete: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osial, M.; Pregowska, A.; Wilczewski, S.; Urbańska, W.; Giersig, M. Waste Management for Green Concrete Solutions: A Concise Critical Review. Recycling 2022, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseldeen Fakhri, R.; Thanon Dawood, E. Limestone Powder, Calcined Clay and Slag as Quaternary Blended Cement Used for Green Concrete Production. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, B.; He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Xiong, T.; Shi, J. A Green Ultra-Lightweight Chemically Foamed Concrete for Building Exterior: A Feasibility Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Tahir, M.F.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Abd Rahim, S.Z.; Mohd Hasan, M.R.; Saafi, M.; Putra Jaya, R.; Mohamed, R. Potential of Industrial By-Products Based Geopolymer for Rigid Concrete Pavement Application. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 344, 128190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, F.M.-W.; Oyeyi, A.G.; Tighe, S. The Potential Use of Lightweight Cellular Concrete in Pavement Application: A Review. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, G.O.; Bassey, D.E.; Olukanni, D.O.; Ngene, B.U.; Adegoke, D.; Odetoyan, A.O.; Kareem, M.A.; Enabulele, D.O.; Nworgu, A.T. Waste Materials in Highway Applications: An Overview on Generation and Utilization Implications on Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, V.; Ramachandran, D. Green Concrete Mix Using Solid Waste and Nanoparticles as Alternatives—A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 162, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Heede, P.; De Belie, N. Environmental Impact and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Traditional and ‘Green’ Concretes: Literature Review and Theoretical Calculations. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Singh, G.; Singh, M. Recycle Option for Metallurgical By-Product (Spent Foundry Sand) in Green Concrete for Sustainable Construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaber, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Barriers and Enablers to the Adoption of Circular Economy Concept in the Building Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Tan, J.S. Green Building Project Management: Obstacles and Solutions for Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Ji, X.; Liu, G.; Ulgiati, S. Evaluating the Transition towards Cleaner Production in the Construction and Demolition Sector of China: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.T.P.; MacGregor, C.; Wilkinson, S.; Domingo, N. Towards Zero Carbon Buildings: Issues and Challenges in the New Zealand Construction Sector. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhelal, E.; Shamsaei, E.; Rashid, M.I. Challenges against CO2 Abatement Strategies in Cement Industry: A Review. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 104, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golizadeh, H.; Hosseini, M.R.; Edwards, D.J.; Abrishami, S.; Taghavi, N.; Banihashemi, S. Barriers to Adoption of RPAs on Construction Projects: A Task–Technology Fit Perspective. Constr. Innov. 2019, 19, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, C.; Haichert, R.; Podborochynski, D.; Wandzura, C.; Taylor, B.; Guenther, D.; Cherry, D. Integrated Mechanistic-Based Framework for Sustainable “Green Street” Rehabilitation of Urban Low-Volume Roads. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2205, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foth, M.; Guenther, D.; Haichert, R.; Berthelot, C. City of Saskatoon’s Green Streets Program—A Case Study for the Implementation of Sustainable Roadway Rehabilitation with the Reuse of Concrete and Asphalt Rubble Materials. In Proceedings of the Green Streets and Highways 2010, Denver, CO, USA, 14–17 November 2010; pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Debele, S.E.; Sahani, J.; Rawat, N.; Marti-Cardona, B.; Alfieri, S.M.; Basu, B.; Basu, A.S.; Bowyer, P.; Charizopoulos, N.; et al. An Overview of Monitoring Methods for Assessing the Performance of Nature-Based Solutions against Natural Hazards. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 217, 103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintara, R.; Yadiati, W.; Zarkasyi, M.; Tanzil, N. Management of Green Competitive Advantage: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Economies 2023, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Enhance Environmental Commitments and Green Intangible Assets toward Green Competitive Advantages: An Analysis of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.M.S.; Islam, K.M.Z. Examining the Role of Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility in Building Green Corporate Image and Green Competitive Advantage. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2021, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Giordino, D.; Zhang, Q.; Alam, G.M. Twin Transitions & Industry 4.0: Unpacking the Relationship between Digital and Green Factors to Determine Green Competitive Advantage. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.-Y.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The Influence of Greening the Suppliers and Green Innovation on Environmental Performance and Competitive Advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polas, M.R.H.; Kabir, A.I.; Sohel-Uz-Zaman, A.S.M.; Karim, R.; Tabash, M.I. Blockchain Technology as a Game Changer for Green Innovation: Green Entrepreneurship as a Roadmap to Green Economic Sustainability in Peru. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Ramsey, T.S.; Hewings, G.J.D. Will Researching Digital Technology Really Empower Green Development? Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Environmental Strategy and Green Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, A.; Yazdani, M.; Mohammed, A.; Wong, K.Y. Green Sourcing in the Era of Industry 4.0: Towards Green and Digitalized Competitive Advantages. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 1997–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; An, Y. The Relationship between Technological Innovation and Green Transformation Efficiency in China: An Empirical Analysis Using Spatial Panel Data. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Ahmad, A.; Sroufe, R.; Muhammad, Z. The Nexus between Green Intellectual Capital, Blockchain Technology, Green Manufacturing, and Sustainable Performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 15026–15038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangmin, W.; Yuyao, Y.; Xiangyu, W.; Zhengqian, L.; Hong’ou, Z. New Infrastructure-Lead Development and Green-Technologies: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiades, K.; Dockx, J.; van den Berg, M.; Rinke, M.; Blom, J.; Audenaert, A. Stakeholder Perceptions on Implementing Design for Disassembly and Standardisation for Heterogeneous Construction Components. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2023, 41, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewickrama, M.K.C.S.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Information Sharing in Reverse Logistics Supply Chain of Demolition Waste: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Ding, T.; Xiao, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Concrete Structures with Reuse and Recycling Strategies: A Novel Framework and Case Study. Waste Manag. 2020, 105, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purchase, C.K.; Al Zulayq, D.M.; O’Brien, B.T.; Kowalewski, M.J.; Berenjian, A.; Tarighaleslami, A.H.; Seifan, M. Circular Economy of Construction and Demolition Waste: A Literature Review on Lessons, Challenges, and Benefits. Materials 2021, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, M.; Voordijk, H.; Adriaanse, A. Recovering Building Elements for Reuse (or Not)—Ethnographic Insights into Selective Demolition Practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameezdeen, R.; Chileshe, N.; Hosseini, M.R.; Lehmann, S. A Qualitative Examination of Major Barriers in Implementation of Reverse Logistics within the South Australian Construction Sector. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2016, 16, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, A.; Zanni, S.; Serrano-Bernardo, F. Sustainability in Building and Construction within the Framework of Circular Cities and European New Green Deal. The Contribution of Concrete Recycling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradhassel, A.; Masterson, B. Advancing the Cement Industry’s Climate Change Plan in British Columbia: Addressing Economic and Policy Barriers. In Proceedings of the Economic Implications of Climate Change Session of the 2009 Annual Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–21 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zębek, E.M.; Zięty, J.J. Effect of Landfill Arson to a “Lax” System in a Circular Economy under the Current EU Energy Policy: Perspective Review in Waste Management Law. Energies 2022, 15, 8690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zotto, L.; Tallini, A.; Di Simone, G.; Molinari, G.; Cedola, L. Energy Enhancement of Solid Recovered Fuel within Systems of Conventional Thermal Power Generation. Energy Procedia 2015, 81, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, R.T.; Hiremath, R.B.; Rajesh, P.; Kumar, B.; Renukappa, S. Sustainable Transition towards Biomass-Based Cement Industry: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 163, 112503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessinger, G. Lower CO2 Emissions through Better Technology. Energy Convers. Manag. 1997, 38, S25–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Low, S.P. Barriers to Achieving Green Precast Concrete Stock Management—A Survey of Current Stock Management Practices in Singapore. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2014, 14, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Relationships between Operational Practices and Performance among Early Adopters of Green Supply Chain Management Practices in Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green Supply-chain Management: A State-of-the-art Literature Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H.; Gertsakis, J.; Grant, T.; Morelli, N.; Sweatman, A. Design + Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781351282208. [Google Scholar]

- Hervani, A.A.; Helms, M.M.; Sarkis, J. Performance Measurement for Green Supply Chain Management. Benchmarking 2005, 12, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, S.; Hosseini, M.R.; Nikmehr, B.; Martek, I.; Abrishami, S.; Durdyev, S. Barriers to “Green Operation” of Commercial Office Buildings. Facilities 2019, 37, 1048–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, R.; Bilec, M.M.; Gokhan, N.M.; Needy, K.L. The Economic Benefits of Green Buildings: A Comprehensive Case Study. Eng. Econ. 2006, 51, 259–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Xia, B.; Chen, Q.; Pullen, S.; Skitmore, M. Green building rating for office buildings—Lessons learned. J. Green. Build. 2016, 11, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Pullen, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Bennetts, H.; Wang, Y.; Mao, G.; Zhou, Z.; Du, H.; Duan, H. Green Building Evaluation from a Life-Cycle Perspective in Australia: A Critical Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.B.M.S.; Kutti, W.A.; Nasir, M.; Kazmi, Z.A.; Sodangi, M. Potential Use of Local Waste Scoria as an Aggregate and SWOT Analysis for Constructing Structural Lightweight Concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 2022, 11, 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinzadeh, N.; Ghiasian, M.; Andiroglu, E.; Lamere, J.; Rhode-Barbarigos, L.; Sobczak, J.; Sealey, K.S.; Suraneni, P. Concrete Seawalls: A Review of Load Considerations, Ecological Performance, Durability, and Recent Innovations. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 178, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdal, S.; Mansour, W.; Agwa, I.; Nasr, M.; Abadel, A.; Onuralp Özkılıç, Y.; Akeed, M.H. Application of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete in Bridge Engineering: Current Status, Limitations, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Buildings 2023, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, L.A.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Ajayi, A.O.; Davila Delgado, M.; Bilal, M.; Bello, S.A. Salvaging Building Materials in a Circular Economy: A BIM-Based Whole-Life Performance Estimator. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H.A.; Alaka, H.A.; Kadiri, K.O. Reducing Waste to Landfill: A Need for Cultural Change in the UK Construction Industry. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 5, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, Y.I.; Mishra, A. Green Blockchain—A Move towards Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, L. Biomass-Coal Co-Combustion: Opportunity for Affordable Renewable Energy. Fuel 2005, 84, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Noh, J.; Oh, Y.; Park, K.-S. Structural Relationships of a Firm’s Green Strategies for Environmental Performance: The Roles of Green Supply Chain Management and Green Marketing Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Foliente, G.; Song, X.; Xue, J.; Fang, D. Implications and Future Direction of Greenhouse Gas Emission Mitigation Policies in the Building Sector of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How Does Green Innovation Improve Enterprises’ Competitive Advantage? The Role of Organizational Learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin van Langen, S.; Vassillo, C.; Ghisellini, P.; Restaino, D.; Passaro, R.; Ulgiati, S. Promoting Circular Economy Transition: A Study about Perceptions and Awareness by Different Stakeholders Groups. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.; Edum-Fotwe, F.; Price, A.D. Critical barriers to social responsibility implementation within mega-construction projects: The case of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, A.; Bowan, P.A.; Daiem, M.M.A.; Said, N.; Ebohon, J.O.; Alabdullatief, A.; Al-Enazi, E.; Watts, G. Identifying the Barriers to Sustainable Management of Construction and Demolition Waste in Developed and Developing Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ahn, S.W. Youth Mobilization to Stop Global Climate Change: Narratives and Impact. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Sojobi, A.O.; Zhang, L.W. Green Concrete: Prospects and Challenges. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 1063–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Y.; Gupta, T.; Sharma, R.; Panwar, N.L.; Siddique, S. A Comprehensive Review on the Performance of Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete for Sustainable Construction. Constr. Mater. 2021, 1, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, Á.; López, F.; Framiñan, J.M.; Flores, F.; Gallego, J.M. XPDRL Project: Improving the Project Documentation Quality in the Spanish Architectural, Engineering and Construction Sector. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Gaetani, C.I.; Mert, M.; Migliaccio, F. Interoperability Analyses of BIM Platforms for Construction Management. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbino, S.; Cieri, L.; Rainieri, C.; Fabbrocino, G. On BIM Interoperability via the IFC Standard: An Assessment from the Structural Engineering and Design Viewpoint. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Wong, R.W.M. Towards a Conceptual Framework of Using Technology to Support Smart Construction: The Case of Modular Integrated Construction (MiC). Buildings 2023, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).