Abstract

With mounting concerns about sustainability, significant attention has been directed toward research within the green industry domain. However, existing literature on initial public offerings (IPOs) has overlooked a crucial distinction: investors do not perceive all firms operating in green industries equally. Firms with green business models (GBMs) are more attractive to investors by providing positive signals of future growth potential and sustainability. To reveal this, the study investigates the relationship between GBMs and IPO success by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis. As the Asia-Pacific IPO market accounts for about 60% of IPO volume and value, with Korea actively participating in this global surge, the study used a sample of 150 firms that underwent IPOs between 2016 and 2019 on the Korea Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (KOSDAQ) market. We find evidence that firms with GBMs are more likely to achieve successful IPO outcomes, and GMC also plays a positive moderating role, enhancing the positive link between GBMs and IPO success. However, GMC alone had no significant effect. These findings imply that green signals positively contribute to a successful IPO and that each green signal can have different signaling effects, ultimately contributing to the field of sustainability through signaling theory.

1. Introduction

The Green industry is increasingly drawing more attention, as the Global Risks Report stated that more than half of the world’s top 10 global risks over the next 10 years belong to the environmental sector [1]. The anticipated expansion of the global green technology and sustainability market is remarkable. It is expected to surge from $16.50 billion in 2023 to nearly $62 billion by 2030, with a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20.8% [2]. Countries that believe in the environmental sector’s potential actively foster green industries as opportunities for growth. The European Commission announced the “European Green Deal” as a new growth strategy in December 2019 and promised to provide at least €1 trillion in sustainable investments over the next decade [3]; thus, many European countries have adopted various environmental policies across their economies and societies. The United States and Japan are making efforts to utilize green technology as a new growth engine by integrating it into major industrial fields [4].

For the growth of the green industry as a promising and sustainable industry, more small and medium enterprises (SMEs) involved in the green sector should grow into mid- and large-sized enterprises through IPOs. Guaranteeing the success of IPO companies in green industries is even more difficult because the environmental issues that may arise in the green industry entail great conflict and divergent institutional pressures on stakeholders such as shareholders, customers, local communities, and the government [5]. Moreover, the broad definition of green industries prevents investors from determining which companies are green and making investment decisions. According to Moore, green industries can be broadly defined as those that reduce resource demand or help improve the output of other industries [6]. Even if a firm’s final product is not green [7], work that is partially related to the firm’s greening process is considered a green job [6]. However, investor attention is a scarce resource, and investors’ cognitive capacity and time to process the available information are limited [8]. Moreover, information asymmetry between existing owners and new investors is higher for IPO firms. Thus, useful indicators or information are needed for investors to determine the growth potential and market value of IPO firms in the green industry.

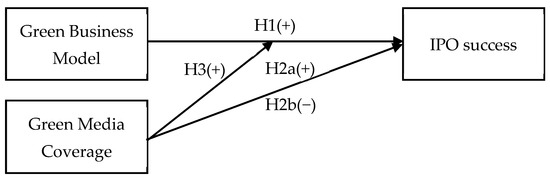

We believe that signals indicating a firm’s growth potential and sustainability significantly impact its IPO success. Therefore, this study examines the effects of two green signals: green business model (GBM) and green media coverage (GMC). First, we suggest that the GBM signals the IPO firm’s growth potential, positively affecting investors and leading to a successful IPO. A GBM is defined as a business approach that prioritizes environmental sustainability as a core value while creating economic and social value [9]. In this study, a GBM refers to a business model designed to capture profits by implementing green practices. Furthermore, we propose that GMC delivers positive or negative signals that can change investors’ perceptions of IPO firms and ultimately affect IPO performance. Green media is known as the media that educates and communicates environmental issues to the public and encourages local communities to participate in them [10]. In this study, GMC refers to the reporting of a firm’s green practices and environmental performance in the media. Figure 1 shows the research model of this study.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

The present study makes several contributions to the research on IPOs based on signaling theory in the context of green industries. First, we focus on two types of green signals: GBM as an internal signal and GMC as an external signal. The findings suggest that certain types of green signals may be beneficial for IPO success. Second, this study presents competing hypotheses on the impact of GMC on IPO success. Third, the empirical results indicate that the interaction effect between the green signals differs from the effect of each signal alone. Fourth, this study enhances our understanding of how firms with GBMs can succeed in IPOs along with GMC.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Green Business Model on IPO Performance

According to Sommer’s [9] taxonomy, a GBM involves adopting environmental strategies that reduce the environmental impact of business operations and integrating environmental sustainability into all aspects of business operations. Thus, the firm can maximize resource efficiency, achieve competitive advantages, respond to stakeholder expectations, and contribute to sustainable development. GBMs can provide environmental improvements along with economic benefits [9].

However, it is not always clear how delivering environmental value translates into profits and competitive advantage for a firm [11]. Moreover, unlike listed firms, little information about non-listed firms is disclosed to the outside world; therefore, information asymmetry is high. In a situation of high information asymmetry, the signal effect of the business model can be observed more clearly. Through IPOs, it is possible to observe how the environmental value provided by green firms is perceived as a positive signal to investors and is eventually reflected in the firm’s value in the market.

Most studies on the performance of green firms deal with the investment performance targeting green firms, and there are two major conflicting views: underperformance and overperformance hypothesis. The underperformance hypothesis [12,13] argues that green funds perform poorly because of reduced portfolio diversification potential and the additional costs incurred by green firms in complying with high-level environmental standards [14]. In contrast, the overperformance hypothesis [15,16,17,18] insists that green investment brings higher returns to investors because green firms have a competitive advantage through more efficient use of resources [17], and they avoid additional costs caused by corporate crises or natural disasters [19]. The reason for such mixed research results on the performance of green investments is that green funds or portfolios were mostly composed of firms with high environmental scores without considering whether they have a GBM.

Meanwhile, many firms in the green sector appeared when IPOs were active, and studies on the IPO performance of green firms were highlighted. Chan and Walter [19] found positive and statistically significant buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHARs) for green IPO firms. Baker et al. [20] reported that a higher environmental, social, and governance (ESG) rating IPO firm is associated with lower information asymmetry, leading to higher valuation. Anderloni and Tanda [21] and Wang et al. [22] found that green firms have lower IPO underpricing. However, existing studies on IPO performance mainly approached it from a green finance perspective and did not reflect the impact of GBMs on IPO performance. Despite the growing interest of academics and professionals, few empirical studies have demonstrated the link between a firm’s GBM and IPO performance. Therefore, we suggest that the firm’s business model should be considered in the literature on IPO performance.

The positive outcome of the overperformance hypothesis can also be applied to firms with GBMs. Firms with superior environmental performance may reduce capital constraints and provide better access to finance [23], and firms that have adopted environmental standards have higher labor productivity owing to organizational changes [24]. According to the overperformance hypothesis, IPO firms with GBMs will raise more capital and receive higher market valuations because of reduced capital constraints and increased labor productivity. The large-scale resources procured through IPOs will be used to grow green firms by expanding their research facilities, hiring new people for R&D projects, and entering overseas markets.

The environmental issues that may arise in green industries tend to be complex therefore, information asymmetry between IPO firms and new investors can intensify. Due to the nature of environmental information that is difficult to measure and monetize, environmental information asymmetry between internal and external firms is critical [25]. “Greenness” is a positive and valuable financial indicator for investors [26]. Improving the flow of sustainability-related information to external stakeholders prior to an IPO reduces information asymmetry, which will improve investment decisions and lower listing costs [27]. For example, firms can obtain more bank loans and reduce debt financing costs by disclosing environmental information [25]. Thus, GBMs can be regarded as positive growth potential signals and useful financial indicators for IPO firms to communicate with investors.

Cost, which has been identified as the main cause of the underperformance hypothesis, can be a problem for firms that are only related to the green sector but do not have a GBM. However, firms with GBMs provide a strong internal signal to investors that they can generate sufficient returns to overcome the costs. This internal signal is stronger and more positive in an environment of information asymmetry and limited public information about IPOs.

We ultimately argue that firms with GBMs will receive higher market valuations at IPOs because investors see the environmental sustainability of GBMs as a sign of high-quality management with long-term growth potential.

Hypothesis 1.

IPO firms’ green business models will positively impact IPO success.

2.2. Green Media Coverage on IPO Performance

This study postulates that the media coverage of an IPO firm is an important signal for investors. The media are information intermediaries in the stock market because they can reach broad audiences and disseminate information [28,29,30,31]. Media reports are the result of opinion leaders’ selection and interpretation of information about a firm, which affects public opinion [32]. Knowledgeable writers, often called opinion leaders, such as financial analysts, and industry experts, write media reports [29] and choose which firms to report on and how to report on them. However, it is challenging for newly listed firms to receive media attention [29]. For entities attracting media focus, the media holds significant influence in developing intangible assets specific to the organization, such as reputation, status, and identity [32,33,34]. This process of legitimization becomes particularly crucial in the context of newly established ventures [35]. Hence, green media coverage of IPO firms is noteworthy, and investors regard it as a critical external signal for IPO firms.

The legitimacy signal sent by GMC increases the likelihood of IPO success by reducing the liability of market newness of IPO firms. Market newness liability refers to the discount investors apply to newly listed firms. IPO firms are not publicly traded; therefore, investors do not know whether they have the resources and abilities to survive in the market. Thus, investors place a discount on IPO firms [36]. Legitimate firms have a high chance of survival because they can easily acquire resources [37,38,39]. Therefore, investors apply less discount to legitimate IPO firms, and the liability of market newness is alleviated. In summary, GMC benefits IPO success by sending legitimacy signals that reduce the market newness liability.

Hypothesis 2-a.

Green media coverage will have a positive impact on IPO success.

Although stakeholders are concerned about environmental matters, they find assessing corporate green practices and environmental performance difficult [40]. It is more challenging to distinguish between firms with good environmental performance that positively communicate their environmental performance and greenwashing firms. Greenwashing refers to any communication or behavior that misleads people to adopt overly positive beliefs about an organization’s environmental performance, practices, or the environmental benefits of a product or service [41]. Greenwashing firms have poor environmental performance, but they positively communicate about environmental performance [42].

Available and accessible information on a firm’s green practices and environmental performance can reveal the differences between green practices and green communication [43]. However, compared to public firms, IPO firms have limited public information other than IPO filings and few analyst forecasts or analyses that can be used as references for market valuation [44]. Thus, the limited public information on IPO firms makes it difficult for investors to discern the difference between actual green practices and mere green communication. Furthermore, investors may hesitate to invest in IPO firms and judge them as greenwashing firms. In the IPO context, where other publicly available information is limited and information asymmetry is high, the risk of greenwashing increases with GMC.

Hypothesis 2-b.

Green media coverage will negatively impact IPO success.

2.3. Moderating Effect of Green Media Coverage on IPO Performance

GMC forms a favorable impression of firms with GBMs by exposing investors to GBMs more frequently. As people are repeatedly exposed to an object, they become more familiar with it [45,46] and reduce their perceived riskiness as investments [47]. Increased media coverage creates favorable impressions of objects [29]. Under the same mechanism, GMC increases investors’ exposure to GBMs; consequently, firms with GBMs can form positive images. Investors tend to invest in firms that signal a positive image [48]; therefore, firms with high GMC are more likely to attract investors and successfully go public.

Media coverage provides a basis for assessing the value of firms with GBMs. Media coverage demonstrates socially proven public evaluations [29,32,49]; thus, investors tend to follow media reports, especially in times of uncertainty [49]. The GBM of IPO firms is relatively new to IPO investors; thus, they are uncertain about the economic efficiency of GBMs. Thus, IPO investors refer to GMC when assessing the value of GBMs. By delivering information on GBMs, GMC encourages investors to identify the economic benefits of firms with GBMs.

Hypothesis 3.

Green media coverage will strengthen the relationship between the IPO firm with a green business model and IPO success.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data

The Asia-Pacific IPO market has maintained its dominant position in IPO volume and value, with an approximately 60% share [50], and Korea is no exception to this global IPO boom. As global asset management firms and large domestic pension funds in Korea set ESG as their primary investment criteria, interest in ESG is increasing in the Korean IPO market [51].

The study uses a sample of firms that went public on the Korea Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (KOSDAQ) between 1 January 2016, and 31 December 2018. Our initial sample comprised 231 IPOs, and we excluded 52 IPOs of special purpose acquisition firms. We eliminated 11 foreign firms and ruled out 18 cases for which financial or media coverage data could not be obtained. The final sample comprised 150 IPOs. Table 1 presents the industrial distribution of the final sample. Following previous studies in the management literature [52,53,54], industries are classified at the two-digit Korean Standard Industry Code (KSIC) (https://kssc.kostat.go.kr:8443/ksscNew_web/index.jsp# accessed on 10 April 2024) level.

Table 1.

Industry Composition of Sample Firms.

We obtained a list of our sample firms, stock codes, and firm nationality from the Korea Investor’s Network for Disclosures (KIND) website (https://kind.krx.co.kr/ accessed on 11 March 2024). The final IPO subscription price, high and low offer prices in the initial filing, number of shares offered in the IPO, number of shares outstanding, list of underwriters, number of employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) shares, number of voluntary lock-up shares of institutional investors, and number of shares allocated to institutional investors were obtained from the IPO prospectuses. The firm establishment date, the total number of shares individual investors subscribed to, and the total number of shares allocated to individual investors were available on the IPOSTOCK website (http://www.ipostock.co.kr/ accessed on 11 March 2024). Share prices, KOSDAQ market returns, KSIC codes, and financial data, such as those for sales, assets, and equity, were extracted from the Dataguide database provided by FnGuide. We obtained media coverage data from the BIGKinds database provided by the Korea Press Foundation.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. IPO Success

We employed the IPO success metric used in previous research in the field of strategic management [55,56,57]. This metric measures the valuations of IPO firms in the financial market. The success of the IPOs was evaluated using four financial indicators. The initial indicator is the net proceeds, which account for the cash the firm receives from the offering minus the IPO expenses. The second indicator is the pre-money market valuation of IPO firms. Pre-money market valuation represents the market value of the sample firm immediately preceding its first trading day [55] and is computed as follows:

where stands for the final subscription price, denotes the total number of shares outstanding, and represents the total number of shares offered in the IPO [55,57].

The third and fourth indicators are each firm’s 90-day market valuation and 180-day market valuation following the IPO. The formula used in the second indicator was adopted here, replacing the final subscription price with the post-IPO price at 90 and 180 days [55]. Following Gulati and Higgins [55], we standardized the four indicators, calculated their mean, added one to all observations, and then took the natural logarithm. The first two indicators, net proceeds and pre-money market valuation, indicate the firm’s market value just prior to the IPO, whereas the latter two indicators, 90-day market valuation and 180-day market valuation, reflect the firm’s early achievements with IPOs [55].

3.2.2. Green Business Model

A GBM is measured by the New Deal Investment Joint Standard created by the Korean government and related institutions. In 2020, the Korean government and president announced the Korean New Deal plans to change the economy from a fast follower to a first-mover economy and from a carbon-dependent to a low-carbon economy [58]. The Korean New Deal comprises two policies: The Digital New Deal and the Green New Deal. The Digital New Deal intends to promote innovation in the Korean economy by enhancing information and communication technology and the Green New Deal aims to achieve a net-zero society by advancing the transition to an environmentally friendly and low-carbon economy [58].

After the Korean government announced the New Deal policy in 2020, the government, related organizations, and experts created the New Deal Investment Joint Standard Practice Manual. The manual consists of two parts, each providing lists of business areas and products covered by the Digital New Deal and Green New Deal policies. The Green New Deal section covers 17 business areas and 85 products, and we used them as criteria for the GBM. Details of the measures are provided in Appendix A.

We checked the IPO prospectus of our sample firm. If the “I. Summary” or “II. Business” section shows that the firm maintains businesses related to Green New Deal products, we judged that the focal firm has a GBM. Our independent variable, the green business model, equals 1 if a focal firm has a GBM and 0 otherwise.

3.2.3. Green Media Coverage

Our second independent variable was the IPO firm’s media coverage of green practices and environmental performance. Following previous research, we measured green media coverage as the number of news articles in the BIGKinds database. Search keywords were “green” and a focal firm’s name. When searching, we put “green” before the focal firm’s name. We examined GMC from three months to the day before the IPO.

3.2.4. Control Variables

We included several variables to control for factors that may affect IPO success. The total media coverage of an IPO firm was controlled and calculated using the number of news articles that mentioned the IPO firm. We searched for the IPO firms’ media coverage from six months to the day before the IPO. We also controlled for firm size and age [55]. Firm size was measured as the natural logarithm of total assets, and firm age was measured as the natural logarithm of the number of months since the firm was founded. A positive correlation exists between past accounting data and a firm’s overall value [59,60]. Hence, we included sales growth and capital ratio. We measured sales growth as the three-year average annual sales growth rate and capital ratio as equity divided by the total amount of assets. If three-year sales data were not available, we used two-year or one-year data.

Price revisions can affect the initial returns of IPO stocks [61]. We calculated our measure of price revision as the ratio of the final offer price to the average of the high and low prices in the initial filing. IPOs managed by esteemed underwriters tend to exhibit diminished initial profits but enhanced long-term gains, as indicated by Michaely and Shaw [62]. A dummy variable for underwriter prestige took a value of 1 if the lead underwriter is ranked as the top five underwriting investment banks in Korea. Therefore, we include the co-managed IPO variable, which takes the value of 1 if the IPO is co-managed and 0 otherwise. If IPO firms allocate ESOP shares to employees, such IPOs are more likely to be underpriced [63]. A dummy variable for ESOP equals 1 if ESOP shares were allocated at the time of the IPO and 0 otherwise. A high commitment ratio of institutional investors implies that they have a positive outlook for IPO returns. The commitment ratio was measured as the number of institutional investors’ voluntary lock-up shares divided by the number of shares allocated to them. Individual investors’ subscription rates reflect their premarket sentiment and are positively related to the initial returns [64]. Our measure of individual subscription rate was calculated as the total number of shares that individual investors subscribed to over the total number of shares allocated to individual investors. To control for market conditions, we included market return, which was calculated as the return on the KOSDAQ index for one month just before the subscription date. In addition, year and industry dummies were included in every regression to capture year- and industry-specific effects. Year denotes the year of the IPO, and industry dummies are based on the two-digit KSIC level classification.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results. The mean value of the GBM was 0.31, indicating that 46 of the IPO firms had GBMs. The average IPO success value was −0.10, with a standard deviation of 0.21. The average GMC was 0.72, with a standard deviation of 2.20. The IPO success measure showed a significant positive association with the GBM but did not show any significant correlation with the GMC. GBM is positively correlated with GMC. About one-third of IPO firms have GBMs and firms go public five years, on average, after their establishment. Firms with GBMs are more likely to receive media attention (β = 0.20, β < 0.01). As firm age increases, GMC (β = 0.17, β < 0.01), total media coverage (β = 0.16, β < 0.1), and firm size (β = 0.26, β < 0.001) increase.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix.

4.2. Regression Analysis

We used Ordinary Least Squares to test our hypotheses. We winsorize all continuous variables at the 1 and 99% levels to mitigate the influence of outliers. Table 3 presents the regression analysis results. Model 1 contained only the control variables. In Models 2 and 3, we added independent variables to test Hypotheses 1, 2-a, and 2-b.

Table 3.

Regression Analysis.

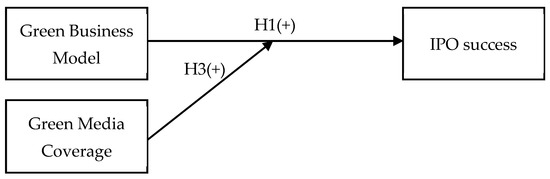

Model 4 includes an interaction term to test Hypothesis 3, which predicts that GMC would positively moderate the relationship between GBM and IPO success. The coefficient of the interaction term in Model 4 was significantly positive (β = 0.026, β < 0.1), supporting Hypothesis 2-a. The main effect of the GBM remains significant and is positively related to IPO success in Models 2 and 4. We also tested the variance inflation factor (VIF), and the VIF values suggested that the estimated statistical results did not have serious multicollinearity issues. The largest VIF value among all models was 2.8. Figure 2 shows the result of our study.

Figure 2.

Updated Research Model.

4.3. Additional Analysis

We conducted an additional analysis to examine whether the results were robust when the media coverage period was shortened to three months. We repeated the regression analyses by substituting the three-month GMC and three-month total media coverage with the six-month GMC and six-month total media coverage. The mean value of the three-month GMC was 0.55, with a standard deviation of 1.73. The average three-month total media coverage was 73.96, with a standard deviation of 59.36.

The results of the regression analyses are presented in Table 4. Model 1 consists of only the control variables. We added our independent variables to Models 2 and 3 to test Hypotheses 1, and 2-a and 2-b, respectively. The GBM is positively significant in Model 2 (β = 0.057, β < 0.1), whereas the GMC in Model 3 has no effect on IPO success. The results support Hypothesis 1 but do not support Hypotheses 2-a and 2-b.

Table 4.

Additional Analysis.

Model 4 contains a positive and significant interaction term (β = 0.037, β < 0.1). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported. The GBM remains significantly positive in Models 2 and 4. The results of the robustness tests demonstrate that the main effect of GBMs on IPO success and the moderating effect of GMC remain significant and positive even when the media coverage period is shortened.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examines how GBMs and GMC affect IPO success. We hypothesized that firms with GBMs and high GMC are more likely to succeed in IPO and that GMC would positively moderate the relationship between GBMs and IPO success. To measure IPO success, we follow the IPO success measure adopted in previous research in the strategic management field. Using a sample of firms listed between 1 January 2016, and 31 December 2019, we found that GBMs are beneficial to IPO success. GMC does not directly affect IPO success but strengthens the relationship between GBMs and IPO success.

This suggests that external signals are significant only when internal signals are provided. Investors regard external signals as secondary signals that supplement internal signals. Specifically, investors believe that GBMs contribute to the high valuations of IPO firms, whereas GMC does not. However, investors use GMC to strengthen GBM signals.

This study makes several contributions to research on IPO success and signaling theory [65]. First, our theoretical arguments and findings reveal that internal and external signals affect IPO success in different ways. The internal signals that GBMs send are critical to IPO success, whereas the external signals delivered by GMC serve only to assist internal signals. Although the media is an important information intermediary [66], the external signals of GMC do not directly affect IPO investors’ investment decisions. In contrast, investors rely on internal signals because they assume that business models can affect corporate value at IPO.

Second, this study advances the literature on signaling theory [67] by examining two different types of signals and how they interact. Previous studies [68,69,70] on signaling theory have focused on the main effect of each signal, and the interaction between two different signals is a relatively unknown mechanism. When investors rely on signals under information asymmetry, they not only interpret each signal independently but also associate the signals. Additionally, even if a signal alone cannot affect investors, its interaction with other signals can have a significant impact.

Third, our theoretical arguments and findings reveal that a GBM is an antecedent of IPO success. Although there has been considerable discussion on the antecedents of IPO success, GBMs have not received much attention as antecedents. As awareness of environmental protection and sustainability is being promoted globally, investors value firms that have GBMs. This study shows that corporate environmental sustainability affects financial markets.

This study had two practical implications. First, start-ups that aim to go public are considered to have GBMs. This study reveals that IPO investors value GBMs. Hence, with GBMs, start-ups can receive significant investor attention and successfully go public. Second, our study suggests that policies supporting GBMs would lead more firms with GBMs to go public and increase their chances of IPO success. Such policies could assist firms with GBMs to survive and generate more profits. Consequently, firms with GBMs can attract more investors and successfully go public.

Our study has some limitations that future research should address. First, the sample is limited to Korean IPO firms. Future studies should conduct comparative research using samples from other countries. Exploring the relationship between GBMs and IPO success or the effect of GMC in various countries is another interesting topic. Second, this study considered the degree of importance of all news articles to be equal. We did not assign weight to articles published by the prestigious press. As prestigious media have a higher readership, articles from them are more likely to be influential. Thus, future studies should consider assigning weights to articles from prestigious publications. Third, this study can be expanded to cover not only the environment but also social responsibility and corporate governance. ESG has received much attention worldwide. The effect of socially responsible activities and corporate governance of IPO firms on IPO success has rich implications for society. Fourth, due to the limited number of IPO samples, we sampled the entire industry so that industry-specific characteristics were not sufficiently controlled. In the future, we would like to extend the sample period to observe the effect of GBMs within an industry.

Author Contributions

These first two authors (J.K. and K.R.K.) contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, J.K., K.R.K. and W.C.; Data curation, J.K. and K.R.K.; Formal analysis, J.K. and K.R.K.; Investigation, J.K. and K.R.K.; Methodology, J.K. and K.R.K.; Project administration, W.C.; Resources, W.C.; Software, K.R.K.; Supervision, W.C.; Writing—original draft, J.K. and K.R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Green New Deal Criteria

| Theme | Area | Product |

| Advanced manufacturing and automation | New manufacturing process | 3D machine vision |

| 3D printing | ||

| Smart factory solution | ||

| Intelligent machine | ||

| 4D printing | ||

| Intelligent 4D scanning | ||

| Robot | Future manufacturing robot | |

| Swarm robotics | ||

| Next generation power unit | High-tech railway | |

| Electric car and hybrid car | ||

| Stirling engine | ||

| Smart car | ||

| Infra structure and services for electric cars and hybrid cars | ||

| High-efficiency and eco-friendly ships | ||

| Smart mobility | ||

| Hydrogen electric vehicle | ||

| Infra structure and services for hydrogen electric vehicle | ||

| Chemistry and new materials | Biomaterials | Bio-derived materials |

| Energy | Renewable energy | Solar cell |

| Solar power | ||

| Biomass energy | ||

| Geothermal power | ||

| Marine energy | ||

| Wind power | ||

| Renewable energy hybrid system | ||

| Large wind power generation system | ||

| Hydro-thermal power | ||

| Hydrogen energy | ||

| Environmentally friendly electricity generation | Fuel cell | |

| Supercritical CO2 power generation system | ||

| Energy harvesting | ||

| Gas turbine power plant | ||

| Energy storage | Constant-pressure compressed air energy storage | |

| Energy storage system | ||

| Energy storage cloud | ||

| Power-to-gas technology | ||

| Lithium ion battery | ||

| Proton exchange membrane fuel cell | ||

| Super capacitor | ||

| Thermal energy storage | ||

| Bio-battery | ||

| Battery energy management system | ||

| Redox flow energy | ||

| Energy efficiency improvement | Home energy management system | |

| Zero-energy building and eco-friendly energy town | ||

| Waste heat recovery | ||

| Off-grid desalination | ||

| Smart HVAC system (HVAC: heating, ventilation, air conditioning) | ||

| Distributed energy system | ||

| Smart grid | ||

| Virtual power plant | ||

| Environment and sustainability | Smart farm | Microorganisms for agriculture |

| Biofertilizer | ||

| Insect breeding | ||

| Smart seed development and breeding | ||

| Environmental improvement | Forward osmosis process | |

| Biofilm water treatment | ||

| Eco-friendly HVAC system (HVAC: heating, ventilation, air conditioning) | ||

| Oil spill clean-up | ||

| Air pollution management | ||

| CO2 capture, storage, and emission source management | ||

| Soil remediation | ||

| Nuclear power plant decommissioning | ||

| Integrated environmental management service | ||

| Resource efficiency management service | ||

| Eco-packaging | ||

| Uni-materialized product | ||

| Environmental protection | Electronic and electric waste upcycling | |

| Plastic upcycling | ||

| Radioactive waste disposal | ||

| Waste-to-energy technology | ||

| Membrane filtration for wastewater treatment | ||

| Noise management | ||

| Indoor air quality management | ||

| Urban mining | ||

| Remanufacturing | ||

| Recycling of renewable energy power system | ||

| Health and diagnosis | Eco-friendly consumer goods | Cosmetics produced by using genetic recombination technology and microbial culture |

| Next-generation treatment | Incrementally modified drug | |

| First-in-class drug | ||

| Information and communication | Realistic content | Smart home |

| Electricity and electron | Next generation semi-conductor | Power semiconductor device |

| Active lighting | OLED lighting | |

| Smart lighting | ||

| Sensor and measurement | Object detection | Non-contact monitoring |

References

- The World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2023; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune Business Insights. Market Research Report; Fortune Business Insights: Pune, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EU). European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Kim, G.; Kang, G.; Choi, W.; Oh, T.; Lee, H.J.; Oh, J.; Lee, J. Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth Strategies EU, U.S, China, and Japan; Korean Institution for International Economic Policy: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kanashiro, P.; Rivera, J. Do chief sustainability officers make companies greener? The moderating role of regulatory pressures. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, M.; Moore, W. Does it pay to be green? An exploratory analysis of wage differentials between green and non-green industries. J. Econ. Dev. 2021, 23, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgetown University Centre on Education and the Workforce. State of Green: The Definition and Measurement of Green Jobs; Georgetown University Centre on Education and the Workforce: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yu, G.; Shen, X. The effect of online environmental news on green industry stocks: The mediating role of investor sentiment. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 573, 125979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, A. Managing Green Business Model Transformations; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemary, R. Green Media. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, F.; Soriano, P. Green and good? The investment performance of US environmental mutual funds. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Cortez, M.C. The performance of US and European green funds in different market conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, N.; Whitehead, B. It’s not easy being green. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1994, 72, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Derwall, J.; Guenster, N.; Bauer, R.; Koedijk, K. The eco-efficiency premium puzzle. Financ. Anal. J. 2005, 61, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; McLaughlin, C.P. The impact of environmental management on firm performance. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Van der Linde, C. Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 33, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, M.; Sen, S.; Roberts, M.C. The rewards for environmental conscientiousness in the US capital markets. J. Financ. Strateg. Decis. 1999, 12, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, P.T.; Walter, T. Investment performance of “environmentally-friendly” firms and their initial public offers and seasoned equity offers. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 44, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.D.; Boulton, T.J.; Braga-Alves, M.V.; Morey, M.R. ESG government risk and international IPO underpricing. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderloni, L.; Tanda, A. Green energy companies: Stock performance and IPO returns. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 39, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Q. Are green IPOs priced differently? Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 61, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Pekovic, S. Environmental standards and labor productivity: Understanding the mechanisms that sustain sustainability. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Mao, X.; Chen, X. Institutional investors’ attention to environmental information, trading strategies, and market impacts: Evidence from China. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.-E.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasheh, M. Freshen up before going public: Do environmental, social, and governance factors affect firms’ appearance during the initial public offering? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 2509–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, E.G.; Lim, J.; Bednar, M.K. The face of the firm: The influence of CEOs on corporate reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1462–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.G.; Rindova, V.P. Media legitimation effects in the market for initial public offerings. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.G.; Rindova, V.P.; Maggitti, P.G. Market watch: Information and availability cascades among the media and investors in the US IPO market. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, P.C. Giving content to investor sentiment: The role of media in the stock market. J. Financ. 2007, 62, 1139–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L. Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolny, J.M. A status-based model of market competition. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 98, 829–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova, A.P.; Rindova, V.P.; Gupta, A.K. No news is bad news: Sensegiving activities, media attention, and venture capital funding of new technology organizations. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 865–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo, S.T. Influencing initial public offering investors with prestige: Signaling with board structures. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.; Oliver, C. Institutional linkages and organizational mortality. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Seppänen, V.; Koivumäki, T. Effects of greenwashing on financial performance: Moderation through local environmental regulation and media coverage. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bc, B.; Liu, B. Non-GAAP measure disclosure and insider trading incentives in high-tech IPO firms. Account. Res. J. 2022, 35, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.A. Mere exposure. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 39–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc, R.B. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, C.; Tversky, A. Preference and belief: Ambiguity and competence in choice under uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 1991, 4, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackert, L.F.; Church, B.K. Firm image and individual investment decisions. J. Behav. Financ. 2006, 7, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Greve, H.R.; Davis, G.F. Fool’s gold: Social proof in the initiation and abandonment of coverage by Wall Street analysts. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 502–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst & Young. EY Global IPO Trends Q2 2023: How Do You Prepare Now for the Moment Your IPO Is Ready to Take Flight? Ernst & Young: Hong Kong, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.H.; Li, M.; Yu, L. Assets in Place, Growth Opportunities, and IPO Returns. Financ. Manag. 2005, 34, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.-C.; Kim, T.-Y. Between legitimacy and efficiency: An institutional theory of corporate giving. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 1583–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, D.D. Managerial political power and the reallocation of resources in the internal capital market. Strateg. Manag. J. 2023, 44, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Siegel, J.I. Paying for legitimacy: Autocracy, nonmarket strategy, and the liability of foreignness. Adm. Sci. Q. 2024, 69, 131–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Higgins, M.C. Which ties matter when? the contingent effects of interorganizational partnerships on IPO success. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limb, S.J.; Sung, S.-Y. The Effect of Pre-IPO Ownership Structure on IPO Success. J. Strateg. Manag. 2005, 8, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, T.E.; Hoang, H.; Hybels, R.C. Interorganizational endorsements and the performance of entrepreneurial ventures. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 315–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Policy Briefing, Korean New Deal. 2020. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148874662 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Krinsky, I.; Rotenberg, W. The valuation of initial public offerings. Contemp. Account. Res. 1989, 5, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J.R. Signaling and the valuation of unseasoned new issues: A comment. J. Financ. 1984, 39, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, K.W. The underpricing of initial public offerings and the partial adjustment phenomenon. J. Financ. Econ. 1993, 34, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaely, R.; Shaw, W.H. The pricing of initial public offerings: Tests of adverse-selection and signaling theories. Rev. Financ. Stud. 1994, 7, 279–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.I.; Choi, W.Y. Effects of ESOP on Underpricing and Aftermarket Performance of IPOs. Korean J. Financ. Manag. 2018, 35, 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.Y.; Kim, J.; Park, J. Individual investor sentiment and IPO stock returns: Evidence from the Korean stock market. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2017, 46, 876–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lim, K.H.; Liang, L. Are all signals equal? Investigating the differential effects of online signals on the sales performance of e-marketplace sellers. Inf. Technol. People 2015, 28, 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, D.P.; Ingram, A.; Tsang, E.W.; Peng, M.W. How do foreign initial public offerings attract investor attention? A study of the impact of language. Strateg. Organ. 2019, 17, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, U.D.; Borah, A.; Kotha, S. Signaling revisited: The use of signals in the market for IPOs. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2362–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.D.; Dean, T.J. Information asymmetry and investor valuation of IPOs: Top management team legitimacy as a capital market signal. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, R. Does presence of foreign directors make a difference? A case of Indian IPOs. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2021, 9, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, D. Are patents signals for the IPO market? An EU–US comparison for the software industry. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).