1. Introduction

Balancing global biodiversity conservation and economic development poses serious challenges [

1,

2]. This is particularly relevant in developing countries where large biodiversity hotspots and poverty-stricken areas overlap, resulting in a constant conflict between conservation and development [

3]. China is the world’s largest developing country, and it has made significant contributions to global biodiversity conservation by implementing large-scale biodiversity conservation measures.

Evaluating the impact of biodiversity conservation policies is a topic of research interest, and some studies have suggested that the conservation policies currently practiced in certain areas may exacerbate biodiversity loss [

4]. Numerous studies have examined the effects of biodiversity conservation policies on income growth, employment, and poverty reduction, particularly in relation to the impact of these policies on income, livelihood, poverty, and well-being from a community development perspective [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In terms of impact mechanisms, studies have shown that financial subsidies [

9,

10], rural labor transfers [

11,

12], transforming the production modes of farmers and industrial structures [

13], and other methods have been used to improve the income levels of farmers and adjust their income structure. However, assessments of the economic effects of these policies have mainly focused on the protection of nature reserves, forests, grasslands, and wetlands, whereas little attention has been paid to fishery resource protection policies.

Fishery resources are associated with aquatic ecosystem restoration and protection [

14]. A report released by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) in 2020 stated that globally, fish stocks were being overfished at a biologically unsustainable level of approximately 34.2%, which would eventually negatively impact important aquatic ecosystems and fishery resources [

15]. To cope with the issue of fishery resource depletion, scholars have proposed implementing licensing systems, fishery management measures, catch quotas, and other restrictive policies [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, some studies have shown that such reduction-centered policies have not resulted in natural control and that vessel reduction policies have not had the desired effect on the overfishing of natural fish resources [

20,

21,

22].

The Yangtze River Basin in China provides a valuable gene pool for freshwater organisms. According to available statistics, the Yangtze River Basin is home to the white dolphin (

Lipotes vexillifer), Yangtze finless porpoise (

Neophocaena asiaeorientalis), Chinese sturgeon (

Acipenser sinensis), Yangtze sturgeon (

Acipenser dabryanus), white sturgeon (

Psephurus gladius), and the Yangtze alligator (

Alligator sinensis), as well as more than 1000 aquatic plant species, all of which are important for national wildlife conservation. However, the rapid economic development in the Yangtze River Basin since the 1980s has led to a dramatic increase in the intensity of anthropogenic activities, such as wastewater discharge, overfishing, sand digging, and quarrying. Consequently, the aquatic ecological environment of the Yangtze River has deteriorated, biodiversity has declined, and the number of endangered wild animals and plants has increased. The biological integrity index of the main stream as well as that of some tributaries of the Yangtze River have reached the “no fish” level, which has caused a decline in the ecological quality of lakes and rivers, as well as fish resources and the income of fishermen [

23]. However, without external support, fishermen may lack the ability to initiate a collective course of action aimed at implementing self-imposed fishing bans [

24,

25]. Therefore, in 2018, the Chinese government established a compensation system for those affected by fishing prohibition in key waters of the Yangtze River Basin. Relevant authorities then successively issued corresponding policy documents that proposed the permanent prohibition of fishing in key water areas of the Yangtze River Basin by 2020. This involved the following: from 1 January 2020, a comprehensive prohibition of fishing was implemented in 332 nature reserves and aquatic germplasm resource reserves in the Yangtze River Basin; from 1 January 2021, a 10-year fishing ban was implemented in key waters of the Yangtze River Basin [

26]. The 10-Year Yangtze River Fishing Ban, which covers the Yangtze River Basin of China, was an unprecedented biodiversity conservation measure and one of the strictest conservation plans worldwide. However, implementing the fishing ban in key water areas of the Yangtze River Basin has significantly improved the protection of the ecological environment of water bodies and the conservation of aquatic biological resources. To properly resettle returning fishermen affected by the fishing ban, the central and local governments have provided special compensation, which is mainly used for boat and net gear, transitional living allowances, and social security for fishermen.

Only a few empirical studies have specifically focused on the income of fishermen [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]; therefore, whether the compensation policy relating to the Yangtze River fishing ban has exerted a positive socioeconomic effect remains unclear. External environmental pressures as well as the internal production structures faced by fishermen in the Yangtze River Basin have undergone profound changes. Exploring the impact of these policies on the income status of farmers is urgent. The livelihood level of fishermen is not only related to the degree of external disturbance pressure but also to their individual ability to withstand such pressure and recover from the resulting damage [

32]. The ability to cope with the economic pressure caused by the regulation of natural resources depends on the socioeconomic status of the people involved, and individuals may respond differently to pressures that affect their livelihoods [

33]. A relatively mature analytical framework and comprehensive index have been formed based on research on the vulnerability of fishermen’s livelihoods [

34,

35,

36]. The ban on fishing in the Yangtze River Basin is currently the most important policy directed at the restoration of biological resources as well as the intergenerational balance between withdrawing from fishing and restoring aquatic biological resources [

37]. As a policy-based compensation system, the fishing ban compensation policy can be classified under the category of ecological compensation [

14]. The implementation of ecological compensation policies is often accompanied by poverty reduction efforts, and the effects of these different policies are variable [

38,

39]. Policies may narrow the social wealth gap [

40], with their impact being reflected via ecological and economic benefits [

41,

42,

43]. Changes in the livelihoods of fishermen, who are affected by these policies, may be attributed to the economic benefits generated by fishing ban compensation policies [

44,

45].

Research has shown that the species diversity index of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River was higher in 2021 than in 2020, which preliminarily indicated that the fishing ban promoted community restoration [

46]. The fishing ban policy on the Yangtze River affected numerous fishermen in numerous areas. This was one of the most unprecedented projects in the history of China’s resource and ecological protection policy and it involved over 270,000 fishermen living along the Yangtze River [

47]. Fishermen are the backbone of fishery production activities and are direct stakeholders of the “compensation for no fishing” policy. They faced issues such as insufficient and unbalanced development when confronted with the short-term and rapid ban on fishing. To ensure the livelihood of returning fishermen, the Yangtze River fishing ban compensation policy recycled fishermen’s nets, boats, and permits in the form of cash compensation. Currently, all fishing ban measures are in place, and all fishing boats are onshore. The implementation of the fishing ban compensation policy has had a positive impact on the livelihoods of returning fishermen [

48]. However, returning fishermen still face the threat of multiple disturbances relating to natural resources and earning income, and the implementation of public policies may alleviate the associated negative effects [

49].

Focusing on the fishing ban compensation policy in the Poyang Lake area, a typical Yangtze river-connected lake in the Yangtze River Basin, we analyzed the impact of “capture prohibition” on farmers’ income and explored their incentives to accept such a change to household income, as well as the transformation in their income creation and non-agricultural livelihoods, from the perspective of relative deprivation of their means of production. This study aimed to explore the effects of the fishing ban compensation policy in the Yangtze River on fishermen’s income. We explored the mechanisms underlying the policy’s effect on income by investigating the possible factors associated with overlapping policies. This helped to clarify the processes by which farmers gradually adopt alternative sources of income following policy implementation, maximize the heterogeneity of sample observations, and evaluate the effect of fishing ban compensation on farmer income in the Yangtze River. Our findings provide new evidence that may strengthen our understanding of the effects of the fishing ban compensation policy in the Yangtze River, assist in recognizing the rights of indigenous residents and local communities, enable the correct handling of conflicts of interest resulting from the prohibition of fishing in the Yangtze River, and promote the optimization of compensation for the fishing ban.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Poyang Lake is located on the southern bank of the Yangtze River, north of Jiangxi Province (115°49′–116°46′ E, 28°24′–29°46′ N). It is the largest permanent freshwater lake connected to the Yangtze River in China. Poyang Lake obtains its water from the Xiuhe, Fuhe, Ganjiang, Xinjiang, and Raohe Rivers (hereinafter referred to as the “five rivers”) and other water systems [

50] and flows into the Yangtze River from Hukou County of Jiujiang, forming a circular water system centered on the Poyang Lake, which is a seasonal lake.

There are 41 islands and seven nature reserves in the Poyang Lake area. Given China’s freshwater fishery germplasm gene pool, Poyang Lake is an important freshwater fishery production base. It is also an important wintering habitat for migratory waterbirds in the East Asia-Australia migration area and forms a crucial portion of the ecological environment in the Yangtze River Basin. The key water source of the Yangtze River Basin, the Poyang Lake area has more than 300 fishing villages and approximately 100,000 fishermen. An investigation of the statistics of the Jiangxi Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs indicated that fishermen with fishing certificates accounted for approximately 70% of the total number of fishermen. Most of the fishermen engaged in first-line operations were aged between 30 and 60 years old, while most were aged between 45 and 55 years old, accounting for 56% of the total number. The overall cultural level of fishermen was low, with the education level of 89.4% of the total sample being junior high school or below. Most fishermen were highly dependent on fishing for their livelihoods (

Figure 1).

In this study, we defined the Poyang Lake area as the complete administrative region near the core water body of Poyang Lake in Jiangxi Province, which acts as the connection zone between the core water body and the five rivers. The region is a complete lake-wetland ecosystem that combines land and water and connects mountains, rivers, and lakes. It forms an important ecological barrier in the core water body that protects the ecological environment. It is an area in which fishing is the most prominent cause of altercations between protection and development. The nine key counties (cities and districts) with the task of fishing ban in the Poyang Lake area are Xinjian District, Nanchang County, Jinxian County, Yongxiu County, Hukou County, Duchang County, Lushan City, Poyang County, and Yugan County. This study focused on the rural areas in Xinjian, Yongxiu, Duchang, and Yugan, which are representative of the Poyang Lake area.

2.2. Research Design and Data Collection

We used a questionnaire to obtain data from farmers in the Poyang Lake area and analyzed desensitization information obtained from the survey. This questionnaire was designed to analyze the relationship between the fishing ban compensation policy and farmer livelihoods. The questions were based on the results of previous studies that targeted rural areas in the Poyang Lake area, the opinions of scientists engaged in wetland ecological protection, and interviews with farmers in the sampled counties. The factors considered were the characteristics of natural resources, fishery production, the fishing ban compensation, and the protection behavior of farmers in the Poyang Lake area. Community surveys were conducted in 10 townships in four typical counties or districts in the Poyang Lake area.

The questionnaire was based on obtaining information about the head of the household, their agricultural planting situation, fishery, or other employment, as well as family income and topics related to changes in the natural resources within the community over two years (2018 and 2021). Therefore, respondents needed to be familiar with their familial situation and have knowledge about planting, aquaculture, and fishing. The final respondents were mostly heads of household, which guaranteed the quality of the questionnaire. To minimize interference from non-policy factors related to income changes, household surveys mainly focused on the income status of households within one year of implementation of the fishing ban compensation policy.

To ensure the accuracy and consistency of information acquisition, we eliminated questionnaires that did not meet the required standards and finally obtained a total of 1311 valid questionnaire samples over a period of two years. Although we aimed to track all sample households, some withdrew from the survey for various reasons such as the relocation of their entire village, the migrant worker status of the head of the household, and other factors. After the questionnaire was completed and farmers who could not be contacted were excluded, the two 2018 and 2021 follow-up surveys included information from 365 households representing 730 samples, which were highly representative of the survey area. From a regional distribution perspective, there were 54, 106, 95, and 106 samples from farmers in the Xinjian District, and the Yongxiu, Duchang, and Yugan Counties, respectively. Nearly 80% of the household heads interviewed were male, and their ages ranged from 51 to 65 years old, indicating that most household heads living in rural areas in the Poyang Lake area were middle-aged and older. The predominant education level was primary or junior high school. The empirical analysis employed data from 365 households.

2.3. Analytical Framework

According to previous research on “land-lost farmers” [

51,

52], the ban on fishing may also be “relative deprivation”. Owing to the lack of effective access to non-agricultural employment and income growth, some farmers faced the risk of being gradually excluded from social development and falling into relative poverty due to unstable income [

53]. This contradicts the original intention of the fishing ban compensation policy for the Yangtze River.

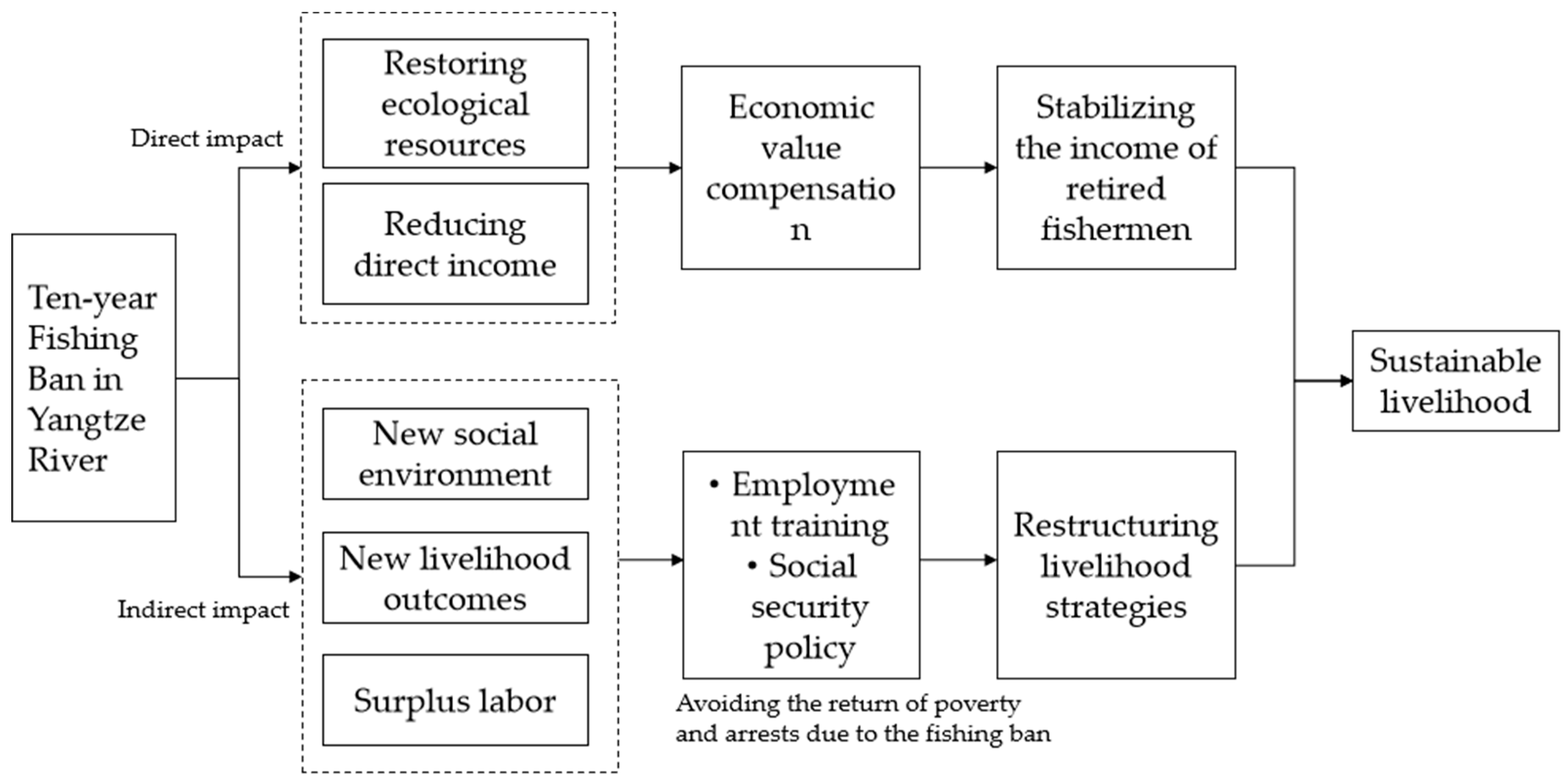

The impact of the fishing ban has attracted much attention, and it is necessary to examine the income issues such farmers are facing and help them improve their employment situation and income. In this study, the income of farmers relates to a state in which farmers’ fishery income is “deprived” due to changes in income levels and structures. Generally, the fishing ban also means that the original production methods of farmers have been destroyed, resulting in a loss of natural resource guarantees that help maintain basic livelihoods and leading to changes in the factor endowment structure of farmers before and after the ban. Owing to differences in endogenous resource endowments, the sustainable development ability of returning fishermen has been affected by policy implementation (

Figure 2).

Some farmers who consider fishing as an important source of income and a theoretical economic unit, insist that the fishing ban, to some extent, has deprived them of their rights. This is reflected in a direct loss of their fishing income and in the series of links related to the practical interests of farmers, such as prohibiting, turning over tools, and compensation disputes. The livelihood strategies of some fishermen changed, and mobility, deprivation, and exclusion also disrupted their well-being. Simultaneously, returning fishermen faced changes to their lives and restructuring, which inevitably weakened their exchange rights and reduced their original savings.

The impact of the fishing ban as an external policy inevitably leads to changes in farmers’ situations. The most intuitive manifestation of this change is that differences in income and other aspects result in farmers adopting non-agricultural and other diverse livelihood strategies, resulting in changes in their well-being. There are significant changes between the income sources and levels of farmers after the fishing ban was implemented compared to those before the ban. Theoretically, continuous differences in their incomes may inevitably lead to a change in the income status of landless farmers with different family endowments. Under the impact of the fishing ban, the short-term income differentiation of farmers and the changes in their income positions may produce a “ranking effect”, with the social group gradually differentiating, causing income groups to change, thereby leading to a deprivation effect on returning fishermen’s income. Research-based evidence indicates that groups with poor resource endowments exhibit greater vulnerability under the impact of “deprivation policies” and that such farmers are more likely to fall into sustained poverty after losing the security provided by a stable natural resource and may also suffer relative deprivation compared with groups with abundant resource endowments.

Farmers often focus on gaining value-added benefits from natural resources, such as employment security, and other essential income sustainability issues. Although returning fishermen under the fishing ban in the Yangtze River Basin are eligible to receive cash compensation for their boats and tools, such phased compensation applies only to wealth stock rather than income flow and it does not relate to all affected farmers. The direct long-term impact of the fishing ban is reflected in the loss of fishery resources, lake contractual management rights, and future value-added income, and this affects farmers in the Poyang Lake area who do not have sufficient alternative livelihoods.

2.4. Definitions of the Variables

(1) Dependent variables: the existing data on the income of landless farmers to simulate the impact of the fishing ban compensation policy on the household incomes of returning fishermen in the key waters of Poyang Lake indicated that receiving compensation would increase current and short-term income levels [

54,

55]. This study used the household incomes and income structures of farmers as standards; thus, the dependent variables included total household, per capita household, agricultural, transfer, and non-agricultural incomes of farmers. All dependent variables were continuous variables. As some variables were valued as 0 prior to conducting the regression analysis, we added 1 (Yuan, Mu, or M) to the continuous variables to transform natural logarithms and used them to eliminate the homoscedasticity and heteroscedasticity of income data and other variables. Further details are listed in

Table 1.

(2) Explanatory variables: the receipt of compensation from the fishing ban was selected as the core explanatory variable in this study. Based on previous research regarding fishing ban compensation, we defined the participating group as 1 and the non-participating group as 0. Participation in the fishing ban mainly involved receiving compensation as follows: (i) one-time compensation for fishing vessels, with prices varying depending on the vessel’s material; (ii) one-time compensation for fishing tools, including fishing nets, cages, and other tools; (iii) 10 years of (tentative) social insurance for farmers participating in the fishing ban, distributed annually. However, due to inconsistencies between the execution and research time linked to this type of compensation, it was not within the scope of this study.

(3) Control variables: in this study, we contend that returning fishermen with certain individual characteristics and human capital advantages have significant income advantages. Therefore, we focused on examining the impact of heterogeneous factors on farmers, including their human, natural, and social capital, which were related to the livelihood and income levels of farmers affected by the fishing ban compensation policy. This study examined the presence of village officials at home, family size, labor force, number of migrant workers, and household arable land area. The income situation of households is influenced by their background and the amount of wealth accumulated; thus, their ability to obtain information varies and may have impacted income.

2.5. Empirical Strategy

We used balanced panel data obtained from the surveys conducted in 2018 and 2021. The propensity score matching double difference (PSM-DID) method was used to empirically analyze the impact of capture prohibition on farmers’ income and explore their incentives to accept such a change in their household incomes as well as the mechanisms underlying their income creation and non-agricultural livelihood transformation.

- (1)

Benchmark model.

To assess the impact of the fishing ban compensation on the income of returning fishermen in the Poyang Lake area, we directly compared changes in the incomes of surveyed farmers before and after the fishing ban was implemented. However, it was difficult to obtain realistic results because differences in the incomes before and after the fishing ban was implemented may have been affected by other policies or environments, such as the agricultural tax reform in 2004 and the wetland ecological compensation in 2014, which were implemented during the same period. To eliminate interference from other synchronic factors, we conducted a quasi-natural experiment on Poyang Lake’s policy evaluation of the “fishing ban compensation policy” and typically adopted the DID method when evaluating other research fields. Selecting this method enabled farmers in the Poyang Lake Basin who received compensation to be defined as a policy participation group, while farmers who did not receive compensation were defined as the policy control group. Thus, farmers who were not affected by the “prohibition of capture” and “return upon capture” during the policy implementation period were identified. The change in the income of these farmers may reflect the impact of policy factors other than the fishing ban compensation in Poyang Lake, which were implemented during the same period. The regression model employed is as follows:

where

i represents farmers,

t represents time, and

is the dependent variable of farmer

i in year

t replaced by income, which mainly includes household and per capita income, and the income structure of farmers.

indicates whether farmer

i participated in the ban in year

t; if farmer

i participated in the ban in year

t, then

= 1; if farmer

i was not affected by the ban, then

= 0.

represents other household-level control variables and township dummy variables that vary over time and affect household income among the surveyed farmers in the sample county;

represents the individual fixed effect of the surveyed household heads in the Poyang Lake area; and

represents the fixed time effect in 2018 and 2021.

represents the estimated impact on income after implementing the basin-wide fishing ban compensation policy.

- (2)

Propensity score matching (PSM).

When evaluating the impact of the fishing ban compensation policy in the Yangtze River on farmer income, it was assumed that the long-term trends in the growth of household livelihoods of farmers who were and were not affected by the fishing ban compensation were similar, and thus, would show similar changing trends. However, field research conducted by the research group indicated that this assumption was invalid. When applying the double difference method to evaluate a fishing ban compensation policy, endogenous issues may cause estimation errors. Therefore, this study used the PSM-DID proposed by Heckman et al. (1998) [

56] for estimation, by referring to other studies on biodiversity conservation policies [

10,

57]. First, PSM was performed on the samples of prohibited and non-prohibited groups, and a first-stage estimation was obtained. This method involved the assumption of individual homogeneity and long-term trend consistency of income growth between the two farmer groups, and the matched samples were used for the following calculation:

where

= 1 indicates that the farmer participated in the prohibition of fishing,

= 0 indicates that the farmer was not banned from fishing, and

refers to observable household characteristics and resource endowments (control variables). In this study, the 1:1 nearest neighbor matching method was selected for matching, and the matching variable was the unified control variable selected in the benchmark calculation.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Increased Income Due to Fishing Ban Compensation on Returning Fishermen

The PSM-DID-based estimation results of the total and per capita income of farmers affected by the fishing ban compensation are shown in

Table 2. The fishing ban compensation had a negative effect on both the total income and per capita income of households, indicating that participating in the ban reduced household income. Returning fishermen were impacted by the policies, but it was not significant.

In terms of the impact of various control variables on the household income of returning fishermen (columns (2) and (4)), the village cadre at home had a significant impact on total household income and a positive impact on the per capita incomes of households (p < 0.1). A 16.5% increase in total income indicated that households had acquired a level of social capital that was conducive to development. Total family population had a negative impact on household total incomes and per capita incomes. The sample group of rural households generally had four to six members, and most were older adults and children. This indicated that rural households with larger populations were more affected by policy shocks owing to their age structure, especially when farmers who had originally relied on fishing for a living temporarily lost their source of income. The size of the labor force and the number of migrant workers had a positive impact on the total and per capita incomes of households. Among them, the number of migrant workers had a significant positive impact on the total household incomes, which could increase income by 8.9% (p < 0.1). This indicated that the availability of more labor would lead to more employment opportunities, with more migrant workers increasing the chances of households generating more non-agricultural employment. Non-agricultural employment allows for the diversification of family development and may increase household incomes and improve the livelihoods of farmers. Family-cultivated land area, an important resource, also had a positive impact on total and per capita incomes, indicating that farming remained a source of income for households in the lake area, but these results were not significant. However, lakeside cultivated land resources in the Poyang Lake area are limited, making it impossible to expand cultivated land area on a large scale; thus, income from plantations is low. In addition, due to recent climate change patterns, which have resulted in extreme weather conditions such as drought and floods, traditional plantations tend to yield limited economic benefits. Distance of the family dwelling from Poyang Lake had a negative impact on total household and per capita incomes, with a significant negative impact on the per capita household income (p < 0.1). When the distance from Poyang Lake was relatively small, resource utilization was limited to a certain extent, and when the distance from cities and towns was large, the farmers’ income was negatively affected.

3.2. Impact of the Fishing Ban Compensation Policy on the Income Structure of Returning Fishermen

The estimated results of the fishing ban compensation’s effect on household farms, household transfers, and non-agricultural household incomes are shown in

Table 3. It is evident that the fishing ban compensation exerted a significant negative impact on household farm income, particularly in Xinjian District and Duchang County, where fishing income accounted for most of household incomes. The fishing ban compensation had a significantly positive impact on household transfer income (

p < 0.01). In the first year of the ban, a buffer period for policy implementation was declared, and farmers who were recognized as professional fishermen or part-time farmers received excessive one-time subsidies. Therefore, although farmers lost all their fishing income during the transition period, they made up for those short-term losses via one-time subsidies. The fishing ban had a significantly negative impact on non-agricultural household income (

p < 0.05). The main alternative livelihood choices available to farmers were non-agricultural livelihood strategies, such as migrant work. However, as it was the first year of the fishing ban compensation, alternative livelihood choices were insufficient, and non-agricultural household incomes were unstable, causing a significantly negative impact.

The impact of each control variable on the income structure of returning fishermen (columns (2), (4), and (6)) indicated that regardless of whether village cadres were at home or not, the number of available laborers had a significantly positive impact on the agricultural incomes from family farms, indicating that large families had a good social capital and that human capital conferred certain advantages with respect to agricultural income. The number of laborers also had a significant positive impact on transfer income, which implied that the greater number of laborers had more fishing tools and participated in more fishing; thus, they received more subsidies during the fishing ban. Families in which more people worked outside had higher non-agricultural household incomes.

The government has implemented a fishing ban during different periods from March to June every year since 2012 in the Poyang Lake Basin. Therefore, except for a few farmers in professional fishermen villages, most chose to find external employment (non-agricultural), are employed locally, or have other forms of employment to increase their family income during the fishing ban. Due to the lack of arable land, some farmers attempt aquaculture of organisms such as crayfish in rice fields, pond lotus root, and gorgon fruit. Farmers who adopted diverse and alternative livelihoods following the fishing ban depended less on fishing income, and thus experienced a lower impact on their income. Income diversity is a key factor associated with resistance to policy risks. Although the 10-year fishing ban in key water areas of the Yangtze River Basin had been in effect for 2 years, the 10-year fishing ban in Poyang Lake had been in effect only for 1 year, and was still in the transitional period; therefore, not all fishermen stopped working and the effect of the policy on the income structure of returning fishermen remained insignificant.

3.3. Impact of the Fishing Ban Compensation Policy on Non-Agricultural Employment of Returning Fishermen

Compared with “land-loss farmers”, a mechanism for compensating returning fishermen has not yet been fully established. Currently, compensation paid to such farmers is dependent on the number of fishing tools (such as boats) they own. Our findings showed that, although it was insignificant, the fishing ban compensation reduced household income because returning fishermen received one-time compensation during the transitional period; however, this amount was only sufficient to protect the fishermen’s livelihoods in the short term. This one-time compensation paid to farmers after the ban was imposed was far below the expected fishing income for the next 10 years. The results showed that household farm incomes were significantly reduced. Therefore, to achieve the long-term goals of the “10-year fishing ban” in the Yangtze River, production and employment must be transformed in a manner that supplements the government’s financial compensation policy, to broaden the availability of channels designed to help farmers find employment. For example, a previous study found that although engagement in outside work has been observed in some surveyed fishing villages, women and older fishermen have insufficient local employment choices, indicating a lack of sufficient skill training and long-term data monitoring support.

As shown in

Table 4, the fishing ban compensation had a significant impact on the affinity of farmers toward non-agricultural employment, especially at the household level, indicating that the fishing ban diverted the livelihood strategy of farmers’ households in the direction of finding external sources of employment. The income of migrant workers is generally higher than that of workers working in single plantations, but detailed continuous studies are required to effectively compare these incomes with fishery incomes. Generally, during the early stages of the fishing ban, direct income exerted a significant effect on behavior; therefore, an increasing long-term income may be required to compel farmers to thrive without fishing.

3.4. Interactive Response of Biodiversity Conservation Policies on Farmers’ Income

In addition to the fishing ban, other biodiversity conservation policies have had an extensive impact and imposed direct restrictions on farmers, including wetland ecological compensation and restoration in the Poyang Lake area. However, the distinction between other policies, such as food subsidies, could not be assessed due to data limitations. Returning farmland to wetlands and wetland ecological compensation policies were implemented in 1999 and 2014, respectively, and have had a lasting impact on farmers. However, the impact of the fishing ban compensation policies that were recently implemented requires further evaluation. Therefore, 365 samples from 2021 were selected for statistical analysis. The number of farmers who were not affected by the three policies was high, and no farmers were simultaneously affected by all three policies (

Table 5).

Farmer samples were affected by a combination of wetland restoration + ecological compensation and ecological compensation + fishing ban policies. Cultivated lands of farmers participating in returning farmland to wetlands were expropriated; thus, their livelihood strategies were limited to fishing or other strategies. Fishery-based farmers were also less involved in planting; therefore, there were fewer compensation samples. These situations are consistent with actual situations. Therefore, it was only possible to compare two cases that participated in the fishing ban and wetland restoration + the fishing ban in the non-participating group.

Based on the data obtained from 365 households in 2021 using the propensity allocation method, K nearest neighbor, kernel, and radius matching were conducted to analyze the impact of wetland protection policies on farmer income and the effect of interaction between policies. The t-statistics of all variables were not significant after matching, indicating that the PSM method was applicable. The effect of the policy on income is expressed in terms of total household income, per capita income, and income structure.

The effect of the fishing ban compensation on the income of returning fishermen is shown in

Table 6. First, in the first year of the fishing ban, farmers with fishermen certificates received a large one-time compensation. This compensation was significantly positive compared to the compensation received by farmers who did not participate in the first year. Second, regarding income structure, the household transfer income of those who participated only in the fishing ban compensation significantly improved, compensating for the loss of fishery income in the first year and significantly reducing the non-agricultural household income due to the lack of adequate alternative income and other factors. Third, the transfer income of farmers affected by the policy of returning farmland to wetlands and the fishing ban also increased significantly, indicating that their household income would not decrease by 2021. The previous analysis indicated that external employment was an important alternative income source for returning fishermen. Therefore, the income of the group affected by the policy improved, and the two policies had a synergistic effect. When both policies act on the community simultaneously, farmers’ income levels improve via compensation and changes in livelihood strategies.

Compared with the previous analyses, in which the impact of other biodiversity conservation policies was included, the fishing ban compensation policy had a significant impact on farmers’ income. Farmers in the Poyang Lake region regard fisheries as an important source of income. Some farmers are professional fishermen with government-issued fishing certificates, while others do not possess fishing certificates but still make a living from fishing. Therefore, the loss of income of farmers participating in the fishing ban compensation was adequately compensated compared to that of non-participating farmers, as they received a large one-time compensation for the loss of almost one year of income. In the future, more forms of diversified compensation and alternative livelihoods are required to maintain the increase in incomes.

4. Discussion

Owing to many factors, such as natural changes and overfishing in the Yangtze River Basin and its tributaries, the aquatic biological resources of the Yangtze River-connected lakes in the Yangtze River are being gradually depleted, as evidenced by the annually decreasing fish supply [

58]. Therefore, to protect the biodiversity of the Yangtze River Basin, the central and local governments have proposed a comprehensive fishing ban in the key waters of the Yangtze River over the previous fishing ban period. In 2019, it was proposed that Poyang Lake and other Yangtze river-connected lakes should implement a “One lake, One policy” differential management plan according to local conditions [

59] and that the relevant provincial government should formulate specific measures aimed at managing the fishing ban.

Whether the fishing ban is a trap for poverty or an opportunity for transformation and development remains unknown. Different studies have provided different explanations. One perspective is that the household livelihood capital coupling coordination degree has significantly improved, and the gap between rich and poor has been narrowed [

28]. However, other results have shown that returning fishermen face severe livelihood sustainability issues when they stop fishing [

27,

30]. We discovered that the fishing ban policy had a significantly negative impact on the household agricultural incomes of returning fishermen in the Poyang Lake area, but it did not have a significantly negative impact on their total household incomes. This was attributed to fishermen receiving fishing ban compensation for their fishing tools, which more than compensated for the loss of agricultural income. The diversification and non-agriculturalization of the livelihoods of returning fishermen in the Poyang Lake area were found to be gradually increasing. However, in the long term, if returning fishermen do not have a stable alternative income source, this may have a significantly negative impact on their household income. Based on the current situation in the Poyang Lake area and the independent choices of farmers, alternative employment appears to be a better livelihood strategy. Only by stabilizing the transfer of fishermen may the fishing ban be effectively implemented and the pressure on policy implementation be reduced [

60]. In contrast, fisheries management in the Amazon is limited to specific species, vessels, and net specifications, which regulates fishing but gives the fishermen little choice of alternative livelihood strategies [

61,

62]. In the Great Lakes region of the United States, where a small amount of commercial fishing still occurs as biodiversity declines, local residents are allowed to fish commercially for subsistence, but the focus of the fishery has shifted to sport fishing [

63].

In the current study, we found that although the fishing ban compensation in the Poyang Lake area exerted a certain incentive effect due to the conflict between the public attributes of fishery resources and the pursuit of individual economic interests by farmers, this incentive remained insufficient to fully compensate the protection costs paid by farmers. Some farmers affected by the fishing ban were also affected by the wetland restoration policy implemented after 1998. Some farmers chose fishing as an alternative livelihood due to the reduction in cultivated land. For example, owing to the implementation of wetland restoration, which was compounded by its geographical location, farmers in the Nanji Township in Xinjian District have recently turned to fishing as their main income source. In 2020, the fishing ban had a huge impact on farmers in Nanji Township, who also had to adapt to the biodiversity protection policy in the Poyang Lake area. Although a large one-time compensation was received, the means of production deteriorated, and returning fishermen lacked effective alternative sources of income and future protection, which could lead to poverty and a fierce conflict between protection and development [

27,

48]. After the fishing ban, most farmers chose to travel outside for work, and labor transfer was eventually recognized as an important means of reducing income loss by the farmers. However, owing to the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020, some farmers neither obtained stable non-agricultural employment nor returned to rural areas to continue fishing. Therefore, following the implementation of a series of protection and development policies, the government should promote the smooth and orderly transformation of local farmers to non-agricultural and diversified production, thereby increasing the income of farmers in the Poyang Lake area and reducing protection costs. In addition, this may reduce their direct dependence on wetland resources and increase the ability of farmers to resist policy-related risks to protect biodiversity in the Poyang Lake area.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

In this study, we discussed the effects of the fishing ban compensation policy on farmer incomes in the Poyang Lake area. The results showed that the fishing ban had a significant negative effect on the agricultural income of returning fishermen but not on the total household income. This may be because returning fishermen were compensated for the fishing ban, which to some extent, compensated for the loss of agricultural income. However, risks associated with policy implementation, such as conflicts between fishermen’s expectations and actual circumstances, may have been encountered [

64]. Although the fishing ban compensation policy in the Poyang Lake area has had a positive impact on the overall income structure of returning fishermen, this positive effect may be short-lived. In the absence of a stable long-term alternative source of income for farmers, this policy will continue to have a significant negative impact on household incomes.

The aquatic ecosystem of the Yangtze River is complex and diverse, with highly diverse fish species, large differences in habitat, and different forms of anthropogenic-related stress. The fishing region in the key waters of Jiangxi Province is mainly concentrated around Poyang Lake. Practical difficulties (such as large groups of fishermen, long fishing histories, disputes and contradictions, and the complex ownership of waters) are commonly encountered. If the remaining multi-interest dimensions of various stakeholders in the fishing ban policy are not simultaneously solved, the effectiveness of the fishing ban goals may not be fully realized. To effectively implement the fishing ban policy in the long term, the following three aspects must be considered during the 10-year period: (i) A large labor force has moved to work outside of the Poyang Lake area. Although local governments have provided many opportunities for re-employment training and positions for returning fishermen, the livelihood transformation of fishermen has a certain periodicity. Due to their traditional livelihood habits, some fishermen find it difficult to adapt to mandatory and regular work environments. During the process of livelihood transformation, some sections of the labor force will become idle, and some areas that have fisheries as their core income source will experience a large outflow of labor. This allows us to further analyze the impact of policies on labor transfer. (ii) The issue of alternative livelihoods for returning fishermen: although fishing ban compensation has been completed in the short term, the marginal decline in the one-time compensation policy dividend for the fishing ban has resulted in fishermen encountering difficulties in developing alternative livelihoods. Between short-term direct economic compensation and long-term social insurance, fishermen were more willing to accept long-term social insurance and other means of protecting their elders (Based on interviews with returning fishermen in the Poyang Lake area). It is necessary to broaden farmers’ livelihood sources and strengthen their livelihood resilience through combined policies designed to coordinate the relationship between protection and development. (iii) Implementation of the fishing ban has effectively alleviated the pressure of biodiversity loss. Due to the characteristics of Poyang Lake itself, numerous “enclosing sub-lakes in autumn” (a unique group of shallow lakes formed by its long-term hydrological and geological processes) will be formed in the dry season, and the fishery resources in the lake will be commercially contracted by farmers for fishing and sales. However, short-term fishing ban policies can effectively restore the population because of the strong recovery ability of economically important fish species. In some areas, the carrying capacity of the environment has been exceeded, resulting in a high death rate and water pollution due to hypoxia, which has negatively affected these areas, contradicting the protection goals (based on interviews with relevant managers of nature reserves in Poyang Lake area). Therefore, sustainable scientific planning of fishery resources is necessary. A simple “ban it” approach is insufficient. Continuously monitoring changes in the diversity of wild species in the Yangtze River to ensure that diversity is gradually increasing and not decreasing is necessary. This is important research that may enable a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy of biodiversity conservation in the Yangtze River.

Our findings may have certain policy implications for many countries or regions with similar backgrounds: (i) The fishing ban policy should not only focus on ecological effects but also on the livelihoods of affected indigenous inhabitants and communities. During the early stages of the fishing ban, arranging reasonable compensation funds to stabilize farmers’ incomes is necessary, and local governments must create a good policy environment to support alternative livelihood development. In this respect, the choice of alternative livelihoods should have an interactive effect with a targeted policy mix, tailored towards local natural resource endowments and an assessment of new negative impacts and pressures affecting biodiversity. For example, seminars, regular skills training, and special financial subsidies should be made available, and local employment opportunities should be increased via the development of ecotourism projects, such as “Migratory Bird Town”. A combination of employment methods should be used to compensate for the loss of household income of returning fishermen to help them transform from traditional fishery livelihoods to alternative livelihoods as soon as possible. Second, considering individual and regional differences, it is necessary to focus on the sustainability and fairness of alternative livelihood development. We expect to track the economic behavior of farmers and improve the benefit-distribution mechanism closely and continuously. (ii) Supplement a new mode of fishery resource utilization. The fishing ban has significantly positively affected the repair of aquatic biological resources (Except for large aquatic organisms such as the Yangtze finless porpoise). Managers of the nature reserve surrounding Poyang Lake have indicated that moderate fishing plays a positive role in the restoration of aquatic organisms and habitat functions of wintering migratory birds. Therefore, we must focus on the recovery dynamics of flagship biological populations, the succession dynamics of aquatic communities in closed lakes, and the risk of alien species diffusion, by regularly tracking and monitoring the ecological effects of implementing the fishing ban to grasp the recovery of aquatic organisms and community succession in real time and initiate countermeasures. The pilot project promotes the “franchising system in Poyang Lake area”, avoids the scope of activities of large aquatic organisms, including the Yangtze River finless porpoise, determines the franchising time, sets quotas, and divides fishing areas based on the recovery of economic fish populations. Instead of destroying aquatic ecological resources and the environment, professional fishermen must fish sustainably according to quotas and realize the ecological dividends of the fishing ban on the Yangtze River. The focus of this study is on the fishermen who lived off fishing but did not receive compensation, and the juxtaposition of fishery resource protection and fishermen’s livelihoods.