4.1. Research Status of the Selected Learning Needs Assessment Articles

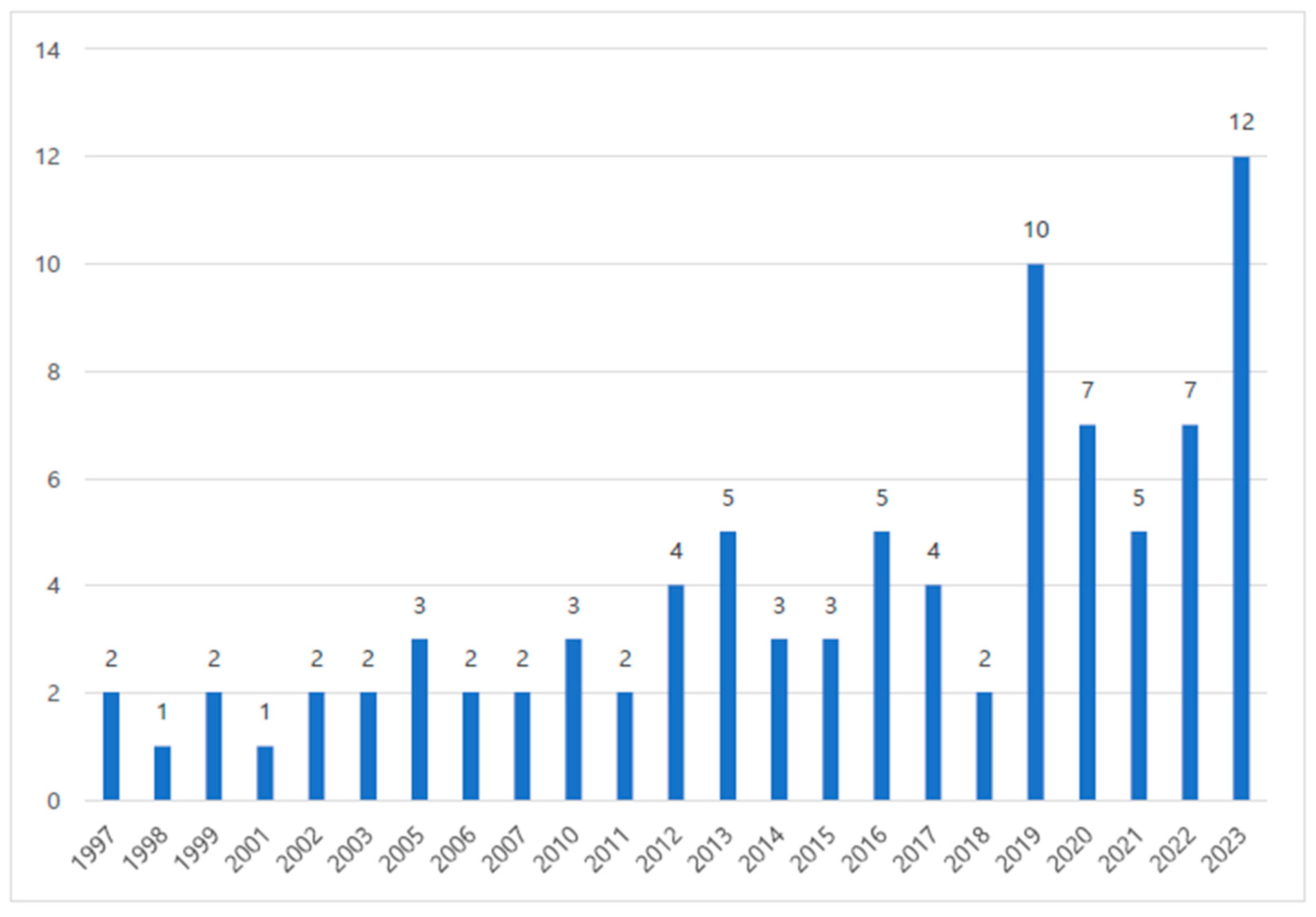

This study examined the research status of the training or learning needs assessment studies published in SSCI journals from January 1997 to November 2023. This encompassed the number of studies per year, the academic fields, the target learners, the contributing countries and continents, keywords, subject areas, and contributing authors and institutions of the 89 selected studies. The finding that more research has been conducted since 2019 compared to previous years is expected given the acceleration in the development and adoption of new knowledge, skills, and technologies evident in recent years. Understandably, these turbulent societal and technological changes would generate greater educational needs than ever before [

21,

22].

Among the 89 studies, the academic fields in which learning needs were identified included education, social welfare, medicine and nursing, business, and psychology. Further analyzing the field of education, the ordered frequencies were teacher education, social welfare, medicine and nursing, higher education, business, psychology, language education, and special education. These findings result from the changing nature of professionals’ standards in every field regarding what practitioners should know and be able to do, along with the emphasis on accountability in the educational sector [

23]. This is especially the case for K–12 teachers and faculty members in higher education institutions.

Regarding target learners, the research on identifying the learning or training needs of medical staff was the most prevalent, followed by those of K–12 teachers, lifelong learners without professional goals, university professors and staff, social workers, K–12 and college students, staff members in companies, and psychologists. Interestingly, the majority of target learners were adults who were beyond the typical age of compulsory schooling. Adults are often required to continuously improve and refine their job-related skills for their own and their organization’s survival and prosperity [

24]. Therefore, they are usually the main target audience of training programs. Notably, most studies identified the learning needs of medical staff. The results of the current study imply that medical staff are increasingly responsible for enhancing their professional competencies in the rapidly changing medical environment [

25,

26,

27]. This includes staying abreast of new developments in patient care, disease management, and treatment methods. Accordingly, there is a critical need for medical staff to have access to and participate in timely training programs. Additionally, the study indicates a growing demand for K–12 teachers to equip their students with essential knowledge and skills for their adaptation to and survival in the living and working environments required by future societies [

28]. According to Bitter and Loney [

29], the knowledge and skills required of students in the future can be acquired through deeper learning which allows for mastering core academic content, critical thinking, problem-solving, effective communication, the ability to work collaboratively, and learning how to learn and foster academic mindsets; all of which teachers must instill in their students within the classroom. Therefore, it is necessary to consistently provide in-service and pre-service teachers with training programs and curricula related to deeper learning.

Regarding the continents and countries in which data collection identified learning needs, the majority of studies were conducted in Europe and North America, with the highest proportion in the United States. This finding might be attributable to the relatively large investment in workforce professional development within the United States and Europe [

30,

31]. It is noteworthy that significant research has been conducted in Asia and Africa, following the lead of the United States and Europe. In the case of Asian countries, their ongoing economic development would have led to heightened interest in professional development. On the other hand, African countries are presumed to be focusing on the training and talent development of their workforces to overcome their relatively less developed economic situations. SDG 4, which highlights ensuring quality education, is regarded as the hub around which the other SDGs revolve, and conducting training or learning needs analysis is critical in the curriculum implementation process to achieve SDG 4 [

32,

33]. From this perspective, the fact that relatively many studies related to training or learning needs assessment have been conducted in Asian and African countries is considered a positive sign for achieving SDG 4, as well as other SDGs.

The results regarding the frequency of the major keywords and primary subject areas were very closely associated with those regarding the academic fields. In the selected articles, the top keywords, such as “education”, “learning”, or “training”; “needs assessment” or “needs analysis”; and “professional development”, were keywords that frequently appeared in articles in all academic fields. In examining the remaining keywords, “teacher” and “teacher education”, which are typically associated with the field of education, appeared most frequently in the selected articles. Additionally, the most common topic of training or learning programs discussed in the selected articles was teaching competencies for in-service teachers and college instructors, as anticipated. Regarding the leading authors and institutions, only five authors have published multiple articles related to training or learning needs assessment [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], and the University of Birmingham was the top institution that has yielded studies in this area [

34,

35,

36,

37,

40]. These results imply that training or learning needs assessment is a research topic that has attracted attention from various authors and institutions in a range of academic fields.

4.2. Research Design Used in the Selected Learning Needs Assessment Articles

Among the 89 selected studies, quantitative data was used most frequently, followed by combinations of qualitative and quantitative data, and the use of qualitative data alone. Each study collected data through various methods including one-on-one interviews, focus group interviews, observations, multiple-choice questions, open-ended questions, or combinations of these methods. Furthermore, the majority of the studies involved only target learners in the needs analysis procedure, while the number involving stakeholders or both target learners and stakeholders was relatively small. Regarding the types of learning needs, most were related to training areas or topics, followed by configurations of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. In terms of the data analysis methods utilized, the most prevalent approach was content analysis for qualitative data, followed by descriptive analysis with or without content and/or inferential analysis. Surprisingly, the selected studies made little use of specialized needs assessment approaches such as the Borich model [

41,

42]. This finding might imply that researchers paid little attention to theories and systematic approaches specifically associated with learning or training needs assessment. The Borich model, which is the most representative approach for specialized needs assessment and provides value to instructional designers, has the following strengths [

14,

16,

43,

44,

45].

First, the Borich model has a practical advantage in that it can be easily applied without complications related to data analysis and instrument construction [

14]. Another of its advantages might be that it can be utilized for both formative and summative evaluations because of the versatility of the data it generates. Formative data, which disclose the perceived significance of the competencies being taught, can function as a check to assess the training’s relevance and as a guide to determine the need for additional training [

14]. Summative data, which reveal the extent to which trainees have achieved competencies compared with those who used other training programs, can serve as an overall program assessment [

14].

An additional advantage of the Borich model is the format of the instrument for rating the relevance or importance of each competency to trainees’ current job function and their perceived level of attainment in each competency. Borich stated that each competency could be subdivided into “knowledge”, “performance”, and “consequence” competencies in a questionnaire for rating competency attainment levels and could therefore provide a more detailed and comprehensive assessment [

14]. Specifically, the knowledge competency reflects the ability to correctly recall, paraphrase, or summarize understanding of subject information, the performance competence reflects the ability or skill to accurately execute the behavior in a real or simulated environment, and the consequence competency reflects the ability to yield desirable outcomes [

14]. Borich maintained that these distinctions enable respondents to make more accurate judgments in rating each competency attainment level [

14], resulting in more reliable and precise data collection, and ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and efficient training programs. Accordingly, instructional designers should identify three attainment levels (knowledge, performance or skills, and consequence) for each professional competency to reveal more detailed and accurate information on their target learners’ training needs.

Unfortunately, the Borich model has some limitations. The model is grounded in the assumption that performers can objectively and best judge their competencies and the relative importance of each competency required of them [

14]. This assumption appears to overlook the predictable problems associated with using self-report questionnaires. Demetriou, Ozer, and Essau [

46] argued that self-report questionnaires may have critical shortcomings, such as social desirability bias, which is the tendency of individuals to respond in a socially acceptable manner, and acquiescent or non-acquiescent response biases, in which individuals respond in certain ways regardless of the question’s content.

Especially in the case of learning needs assessments, respondents may not provide honest answers to questions related to their knowledge, performance, and consequence competencies due to fear of negative repercussions. They may also struggle to accurately assess their performance and/or consequence competencies due to a lack of objective criteria and information needed for accurate judgments [

46]. Therefore, it can be difficult for performers to assess all aspects of their own knowledge, performance, and consequence competencies accurately and objectively. Consequently, the challenge remains to determine who can accurately and objectively judge performers’ (i.e., prospective trainees’) levels of knowledge, performance, and consequence competencies. To ensure data reliability, it may be advisable to engage multiple individuals and utilize various sources in needs assessment processes.

Another challenge emerges in determining how to perform an integrative analysis of data when multiple individuals or sources are utilized within a needs assessment process. A quadrant analysis model, first used by Gable, Pecheone, and Gillung [

47], can be one of the most appropriate tools for this analysis type. This is because quadrant analysis is performed using a 2

2 matrix wherein one dimension represents the discrepancy between the importance and performance levels of each competency rated by performers and the other represents the discrepancy between the importance and performance levels of each competency as rated by senior managers or immediate supervisors conducting work performance appraisals of their employees. The competencies that fall within Quadrant I constitute priorities in learning needs, while those falling within Quadrant IV could be considered indicators of success [

18]. Additionally, the competencies falling within Quadrants II and III require reinforcement through learning or training. Consequently, to make use of a multi-faceted approach that combines input from different sources and incorporates various assessment methods, instructional designers must adopt a quadrant analysis model to synthesize the collected data.

The most vulnerable aspect of the Borich model lies in its use of the group mean importance rating to address errors arising from individual perceptions of competency importance. In the model, weighted discrepancy scores for each professional competency are calculated for each individual by multiplying the discrepancy score by the group mean importance rating [

14]. Some scholars strongly criticize the use of mean values to describe items measured on ordinal scales due to the inherent limitations of ordinal data and the assumptions made when using mean values [

16,

48,

49,

50]. For this reason, Narine and Harder [

16] recently developed the ranked discrepancy model, which is optimized for addressing ordinal and non-normally distributed data, as an alternative to the Borich model. Consequently, when instructional designers and researchers in related fields utilize a particular approach for specialized needs assessment, they must maximize its strengths and address its limitations to ensure rigorous and precise needs assessments.

The results of this study have implications for future research. Firstly, a considerable number of the selected studies did not employ a multi-faceted approach combining different input sources and incorporating complementary needs assessment methods. Future training or learning needs assessment studies should involve multiple individuals, such as instructors, administrators, or peers, as well as target learners. They should also integrate other indicators, such as relevant test results or performance appraisal outcomes, with questionnaires or interviews to obtain more trustworthy data within the needs assessment process [

46]. It might also be desirable to utilize multiple needs assessment or data analysis methods to balance the strengths and weaknesses of each, and effectively identify the learning needs of the intended learners [

17,

18].

Secondly, many studies have not separately identified attainment levels for each professional competence. To develop effective and efficient training or curriculum structured around the exact deficiencies of target learners, instructional designers must separately identify each discrete competence attainment level for each professional competency [

14], regardless of whether it is assessed in a survey questionnaire or interview.

Lastly, more than half of the studies containing the quantitative analysis component used mean values to determine learning needs. The survey items used in these studies were measured using ordinal scales with results that exhibited non-normal distributions; thus, deriving means and drawing conclusions based on the results could very likely lead to misinterpretations and inaccurate conclusions [

16,

48,

49,

50,

51]. When conducting a survey for a learning needs assessment, it is often necessary to use an ordinal survey. However, in such circumstances, rather than deriving needs based on the mean values of each item, it might be more appropriate to use the mentioned ranked discrepancy model to assess discrepancies between the importance and performance levels of each item [

8,

16,

52]. Consequently, instructional designers and researchers in related fields must exercise caution when selecting a learning needs assessment approach or model based on the nature of needs assessment studies. Their focus and efforts are expected to significantly contribute to assuring quality education and effectively realizing SDG 4, which emphasizes the importance of providing inclusive, equitable, and lifelong learning opportunities for all.