Conceptual Framework and Prospective Analysis of EU Tourism Data Spaces

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Health: Li and Quinn (2024) [36] discuss the European Health Data Space, emphasizing the expansion of the right to data portability. This reflects an approach to improving access to and control of personal electronic health data by individuals. Marelli et al. (2023) [37], Kympouropoulos (2023) [38], and Mateus et al. (2023) [39] discuss the political and public management implications of the European Health Data Space.

- Industry: Alexopoulos et al. (2023) [40] focus on resilient manufacturing value chains, highlighting the importance of reliable data sharing. Farahani and Monsefi (2023) [41] and Bevilacqua et al. (2023) [42] address the application of data spaces in the Industrial Internet of Things and Industry 4.0.

- Environment and climate science: Elia et al. (2023) [43] describe a Data Space for Climate Science within the European Open Science Cloud, emphasizing the need for a transformative approach in data management and analysis. Volz et al. (2023) [44] and Pomp et al. (2023) [45] investigate the use of digital twins and data spaces in resource management and the circular economy.

- Smart cities: Battistoni (2023) [46] addresses how data management and sharing are changing in smart cities, underlining the importance of data coexistence rather than integration. Usmani et al. (2023) [47] and Langer et al. (2023) [48] investigate the integration and analysis of data in sectors such as smart cities and data analytics.

- Military systems: Rettore et al. (2023) [49] propose the concept of Military Data Space, focusing on data fusion to improve decision-making.

- Agriculture: Šestak and Copot (2023) [50] delve into data sharing in agri-food supply chains, highlighting the principles of trust in the Agricultural Data Space.

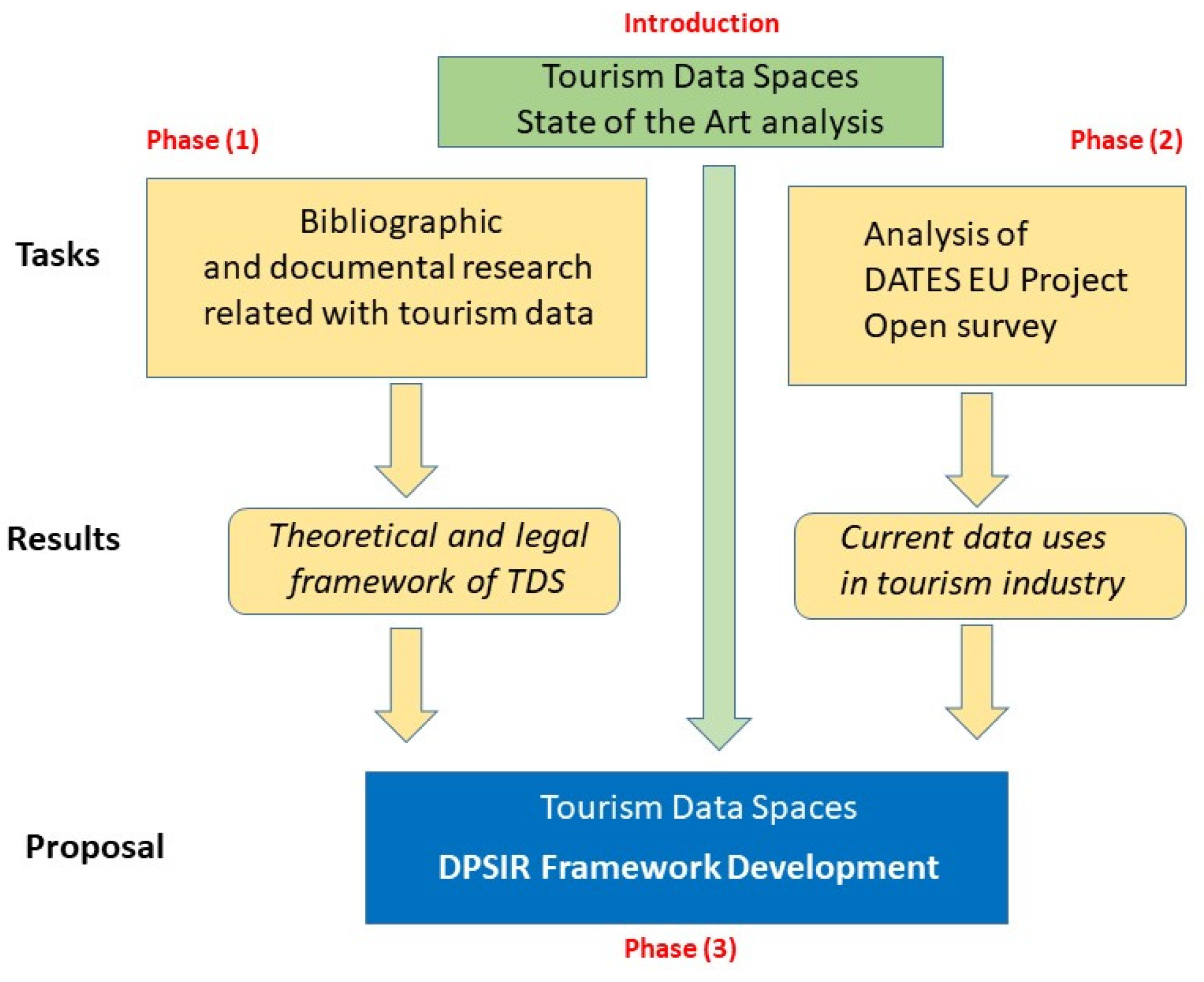

3. Materials and Methods

4. Construction of Tourism Data Spaces: Theoretical and Legal Framework

4.1. From Smart Destinations to Tourism Data Spaces

4.2. Legal Context of Data Sharing in Tourism and Perspectives

- The Data Governance Act, adopted in May 2022, aims to promote data availability, boost intermediaries’ trust, and strengthen data-sharing mechanisms across the EU. Its rules of procedure address the following issues:

- ○

- The reuse of certain categories of protected data held by public sector bodies.

- ○

- Encouragement of the emergence of neutral data intermediaries to facilitate data sharing by connecting data supply and demand.

- ○

- The creation of a harmonised framework to encourage data altruism, whereby individuals and companies give their consent or permission to make the data they generate available—voluntarily and without reward—to be used for purposes of general interest.

- ○

- The establishment of the European Data Innovation Board, an advisory body to assist the Commission in all matters related to the Regulation.

- The Commission adopted the proposed Data Act on 23 February 2022 to ensure a fair distribution of value in the data economy. It establishes new data access and usage rights for Business to Business (B2B), Business to Customer (B2C), and Business to Government (B2G) exchanges, and sets out a framework for efficient data interoperability. The European Interoperability Act, introduced on 18 November 2022, ensures a coherent EU approach to interoperability, allowing public administrations to collaborate on cross-border data transfer.

- The Artificial Intelligence Act, proposed in April 2021, focuses on using AI systems and associated risks, proposing risk-based definitions and classifications. It is relevant for the tourism sector, where AI and generative models, such as ChatGPT, are gaining traction.

- The Open Data Directive, which came into force in July 2019, strengthens the rules on data formats and has led the EC to publish a list of high-value datasets, many of which are relevant to the tourism data space.

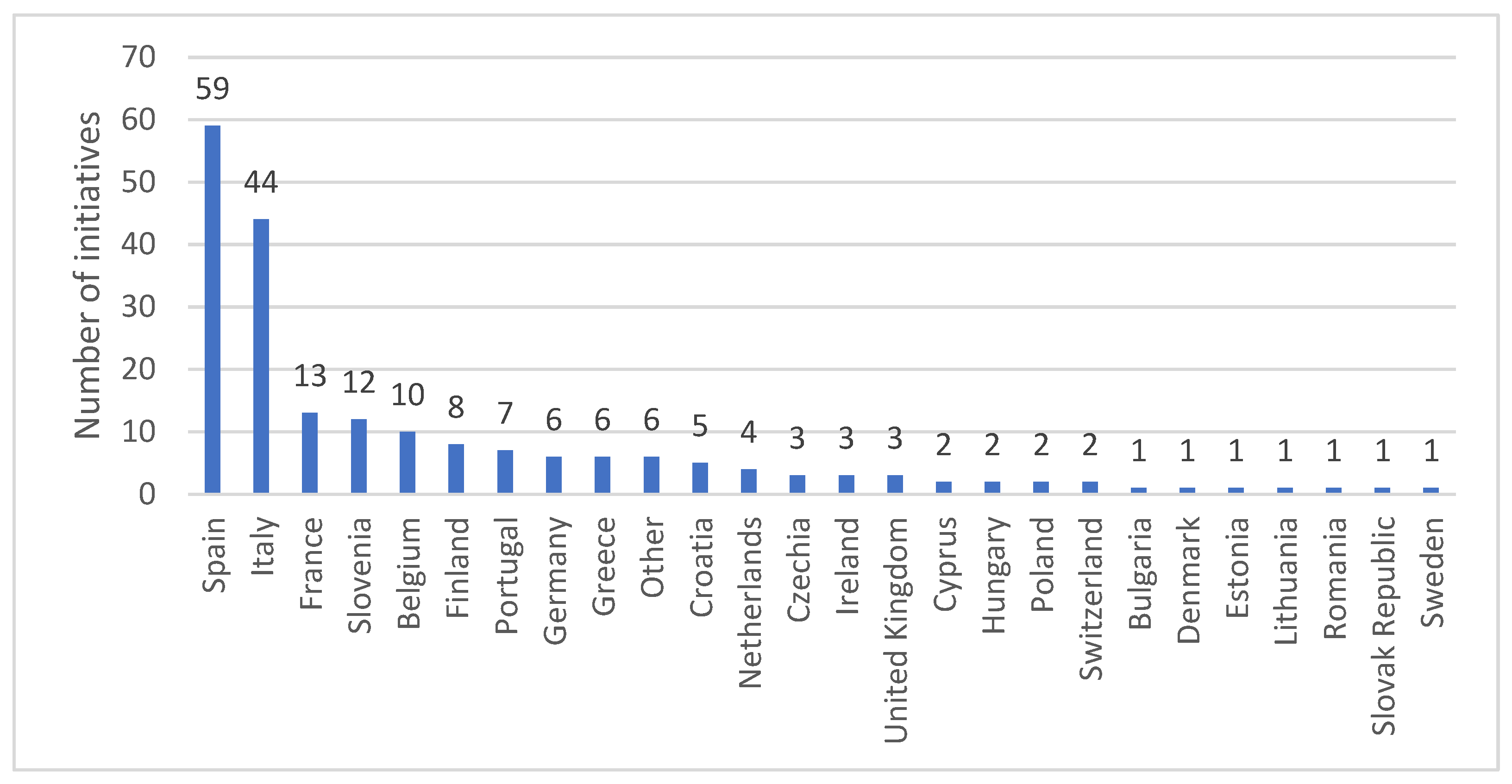

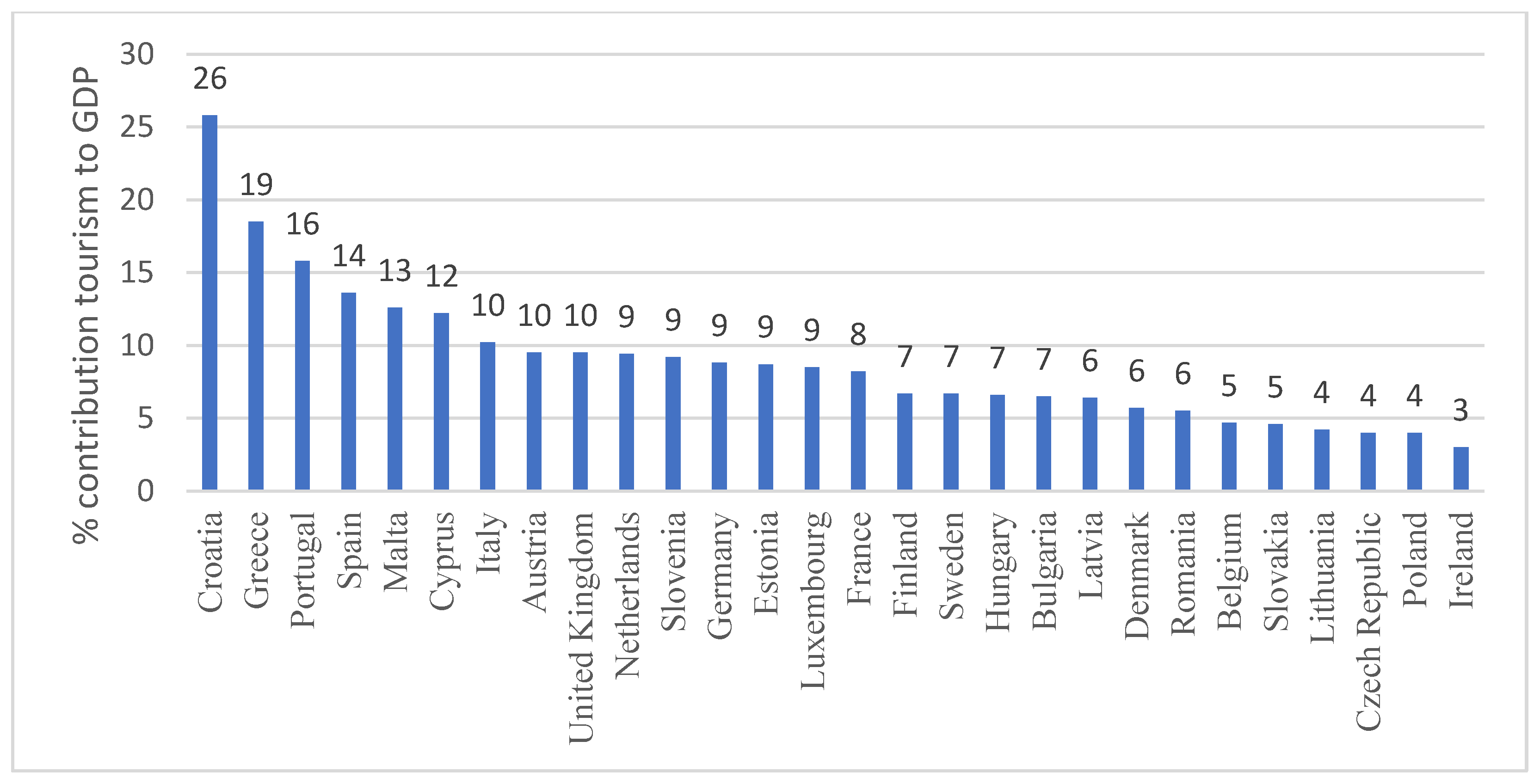

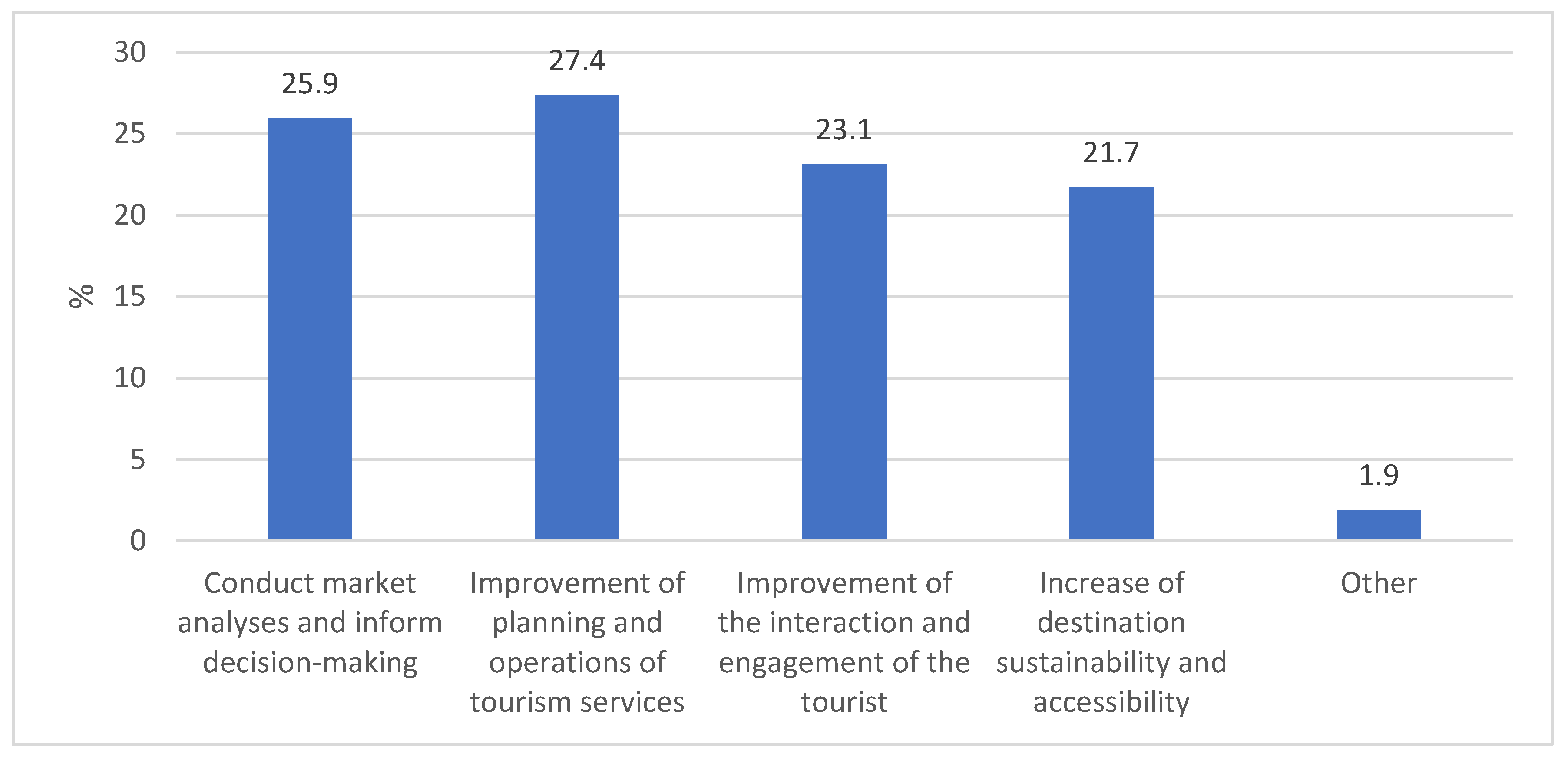

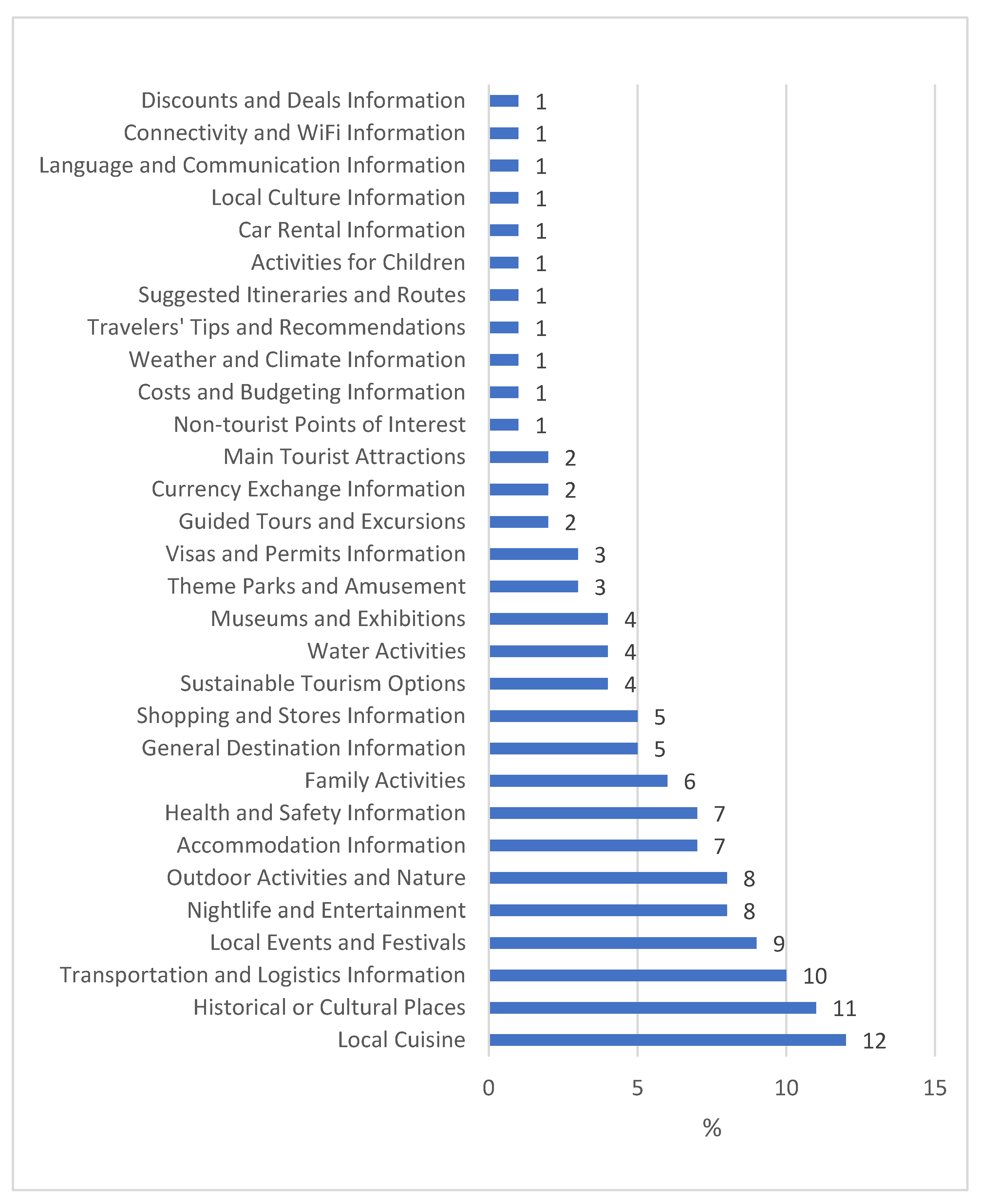

5. Assessment of Current Sharing of Tourism Data

6. DPSIR Conceptual Framework in the Creation of Tourism Data Spaces

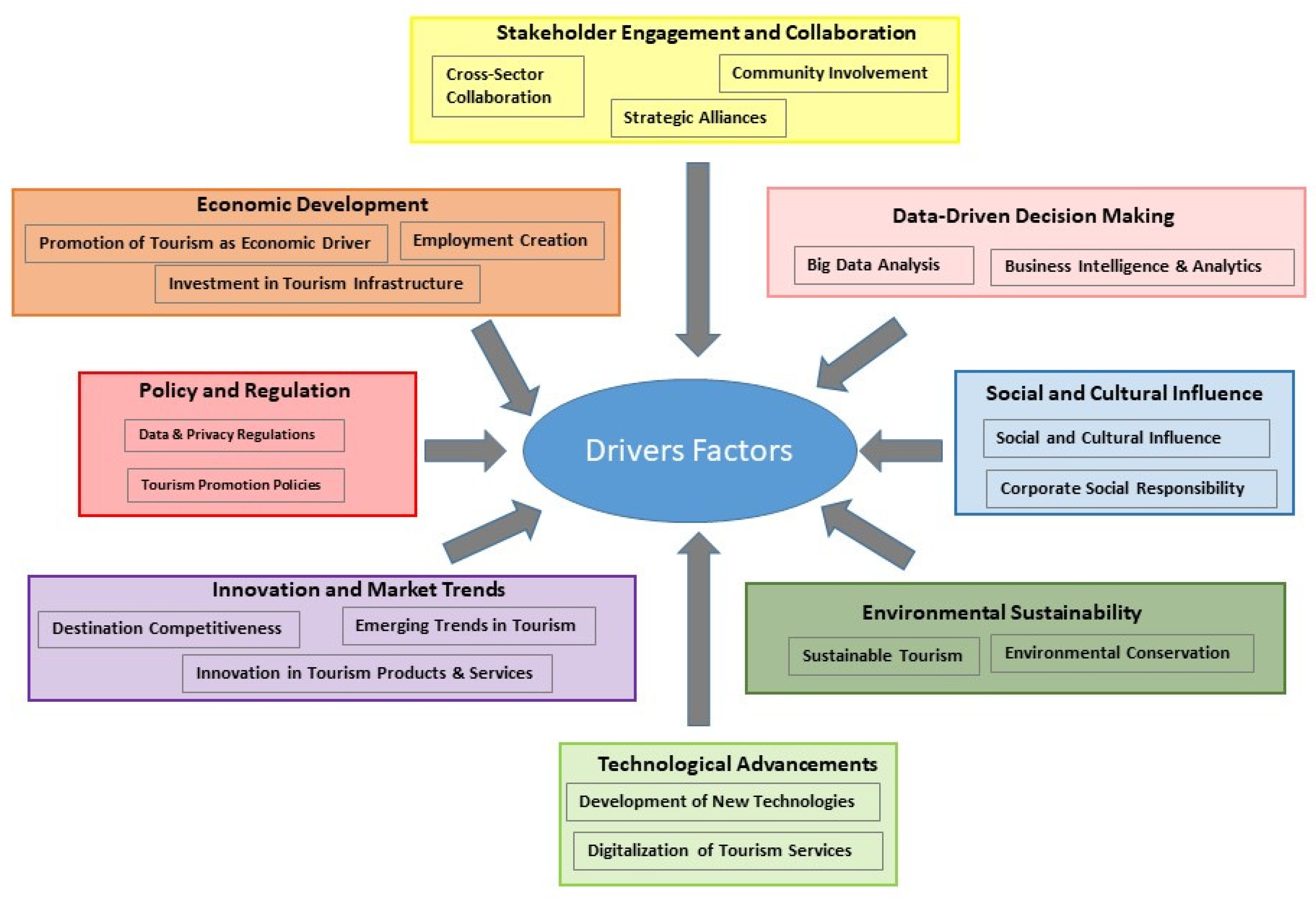

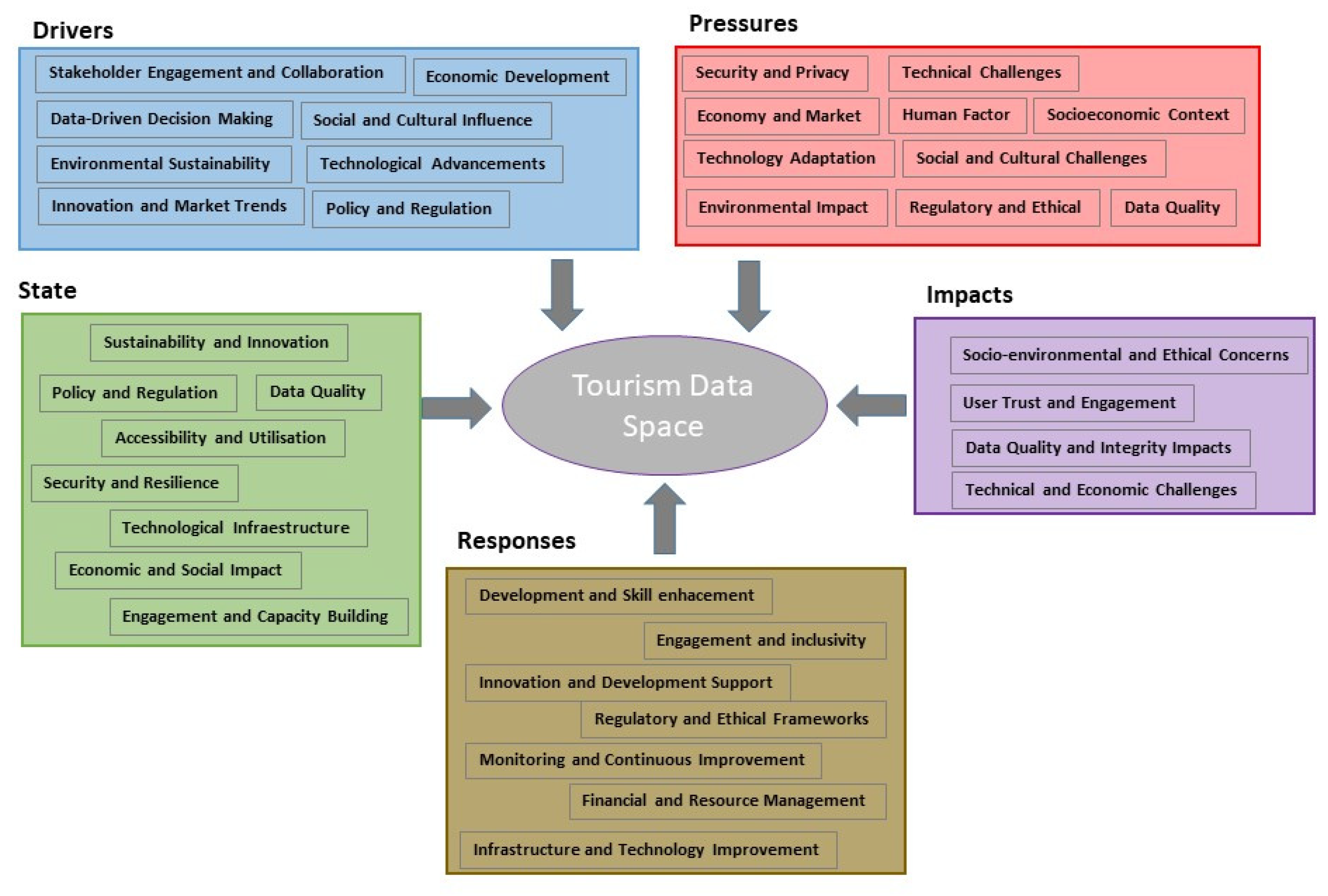

6.1. Drivers

- Innovation and market trends: This cluster comprises the drivers associated with the need to keep up with emerging market trends and constant innovation in products and services. The competitiveness of a tourism destination can be a strong driver for investment in data technologies and the pursuit of differentiation through innovation [95,96].

- Technological advancements: technological advances are a powerful driver for developing a tourism data space, facilitating the digitisation of services and creating new opportunities to enhance the tourism experience [97].

- Environmental sustainability: environmental sustainability has become an important driver for the tourism sector, promoting conservation and sustainable tourism. The creation of data spaces can support these initiatives by providing key information for decision-making and environmental impact monitoring [105,106,107].

- Stakeholder engagement and collaboration: stakeholder engagement and collaboration, including cross-sectoral collaboration and community participation, are essential drivers for sharing and improving tourism data, as well as forming strategic partnerships that benefit all stakeholders [111,112,113].

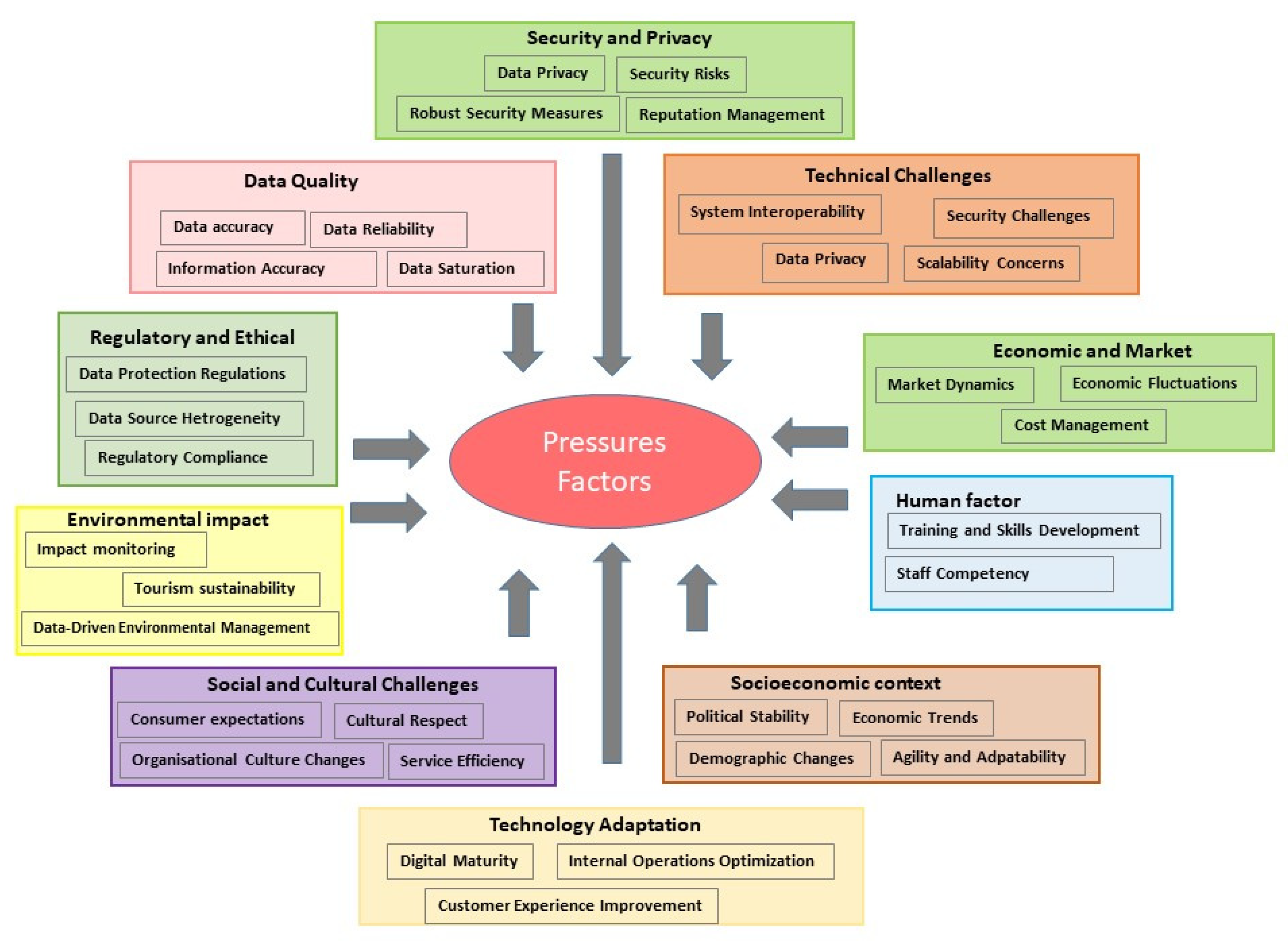

6.2. Pressures

- Data quality: This set of pressures relates to the need to maintain a high standard of data quality. Accurate and reliable data in tourism is critical for planning, marketing and personalising the customer experience. Data saturation and information accuracy can be significant challenges, especially when handling large volumes of data from various sources [114,115].

- Technical challenges: These challenges focus on the technical aspects of data management. Interoperability of systems is a major challenge, as different platforms and tools must work together to share and process data. Technical issues can affect the efficiency, scalability, and security of tourism data [116,117].

- Regulatory and ethical: Regulations and ethics are crucial in managing tourism data. Regulation changes, such as data protection laws (GDPR in Europe, for example), may restrict how data is collected, stored, and used. In addition, there are ethical concerns related to the privacy of tourist data and the responsible use of information [118,119].

- Economic and market: Market dynamics and associated costs are significant pressures. The tourism market is highly competitive and subject to rapid economic fluctuations. Businesses must balance the costs of data technology and infrastructure with the need to maintain competitive prices and generate profits [120,121].

- Social and cultural: Consumer expectations and organisational culture changes can pressure tourism data management. Tourists increasingly demand personalised experiences and fast and efficient services, which require smart use of data. In addition, companies must adapt their approach to respect diverse cultures and social behaviours [122,123].

- Technology adaptation: Major challenges include adopting new technologies and closing the digital maturity gap. The tourism sector must keep up with the latest digital technologies to improve customer experience and optimise internal operations, which can be difficult for organisations with limited digital skills or technology infrastructure [97,124].

- Security and privacy: Data privacy protection and security risks are a major concern. Data security incidents can damage the reputation of tourism businesses and diminish consumer confidence. Businesses should implement robust security measures and ensure personal data privacy is handled appropriately [125,126].

- Environmental: The environmental impact of tourism activities and sustainability are increasingly important issues. Data can help to monitor and manage environmental impact. However, there are also pressures to ensure that the data practices are sustainable and do not negatively affect the environment [127,128].

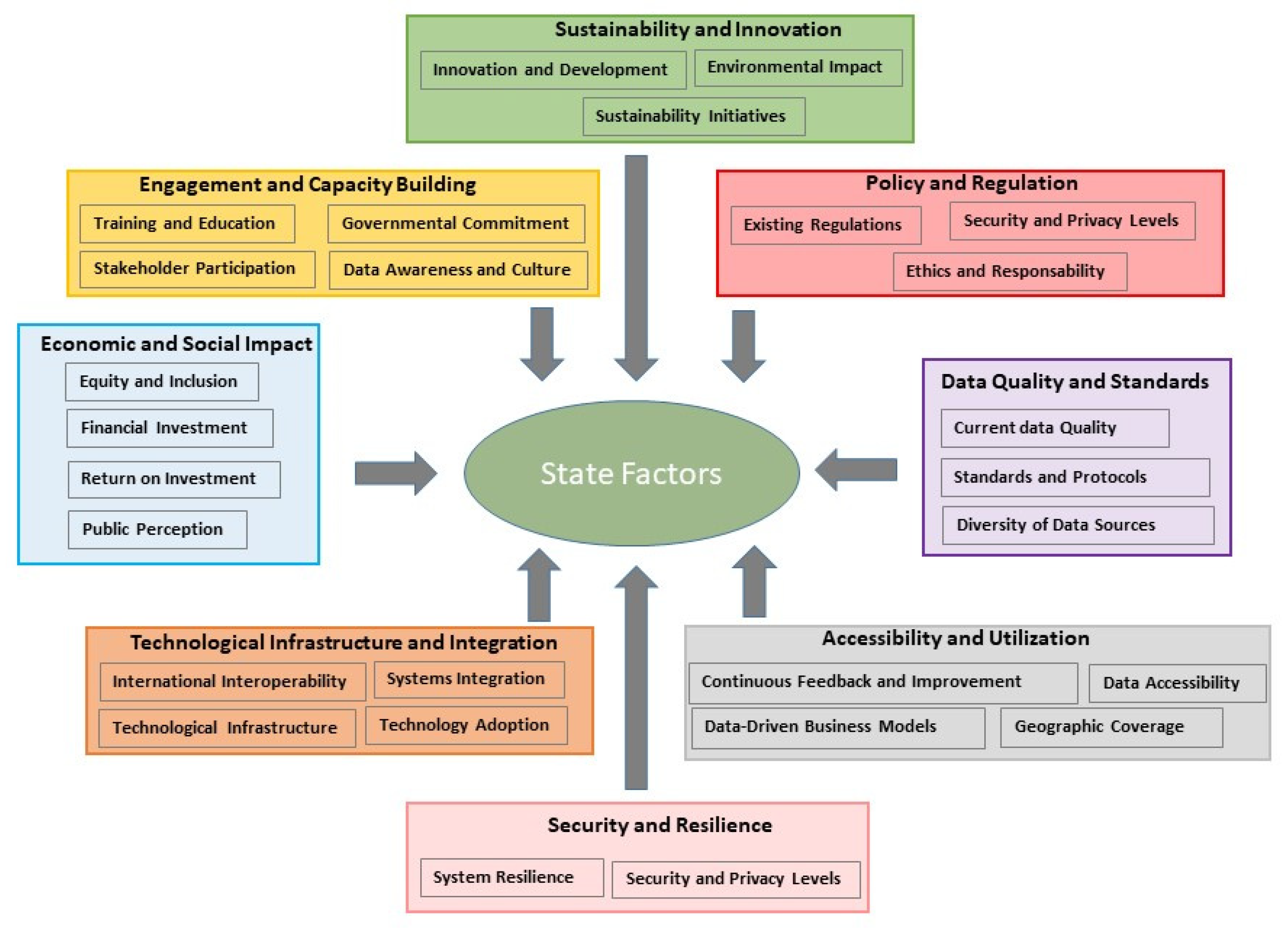

6.3. State

- Technological infrastructure and integration: Technology is the foundation that enables the operation of a data space. The integration of systems and the adoption of advanced technologies are crucial for efficient management and interoperability both locally and internationally [137].

- Policy and regulation: Regulations define the framework within which data can be shared and used, while security, privacy and ethics policies ensure that data is handled responsibly and securely [140].

- Sustainability and innovation: Continuous innovation and sustainable development are fundamental to maintaining the relevance and accountability of the data space. This group also considers the environmental impact of the technological infrastructure used.

- Accessibility and utilization: Accessibility and usability of data are essential for the tourism data space to be effective. Extensive geographic coverage and constant feedback promote improving and updating the data space [141].

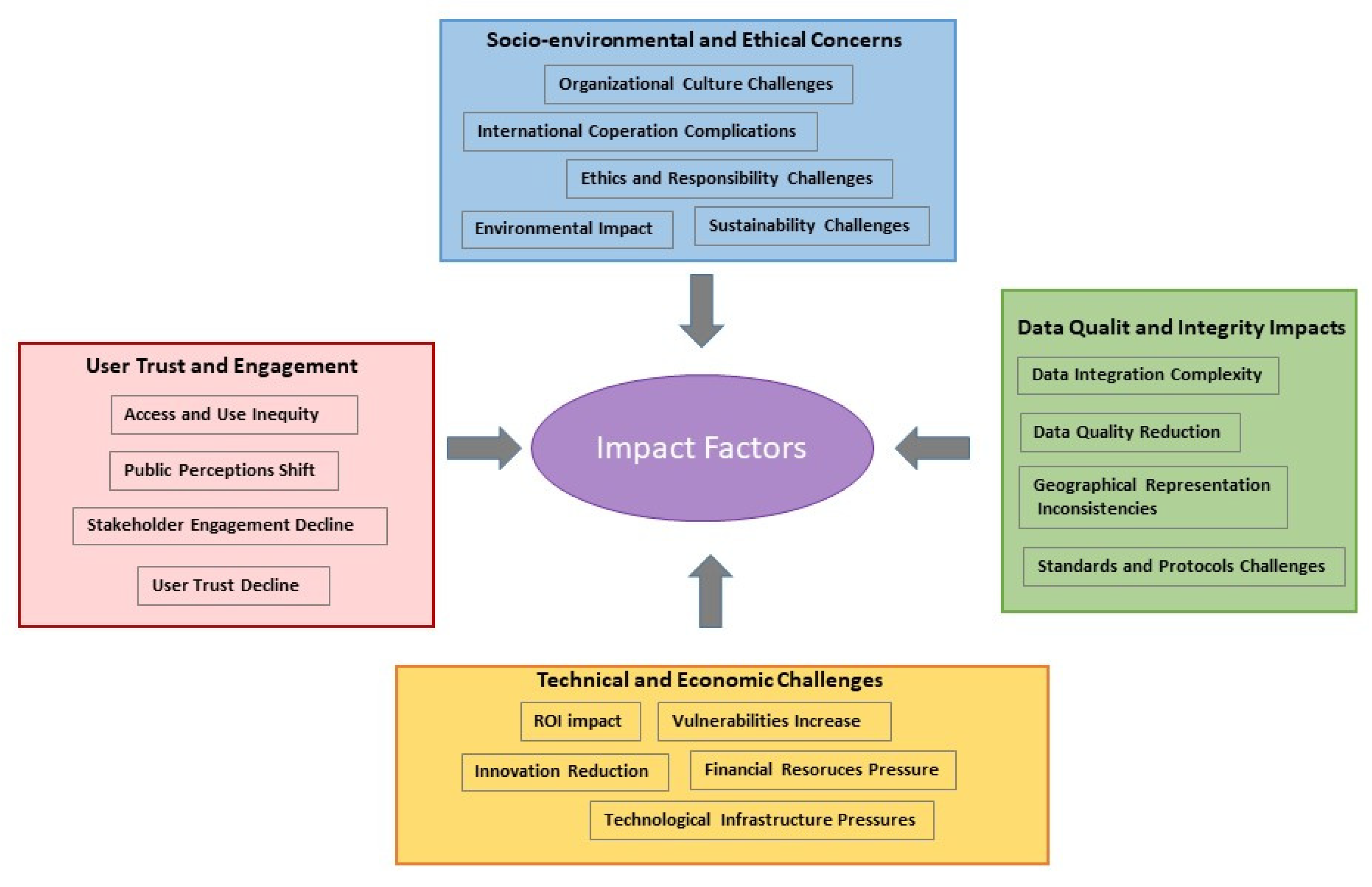

6.4. Impact Factors

- Data quality and integrity impacts: Data integrity is fundamental to the utility of the data space. Saturation, complexity, and geographic inconsistencies can undermine accuracy and utility, which can have environmental impacts through the misdirection of resources in sustainable tourism strategies, social impacts by not reflecting or misinterpreting the needs of local communities, and negative economic impacts in decision-making based on poor data [141].

- User trust and engagement: User trust and engagement are vital to the success of the data space. Trust issues and inequalities in access and use can lead to less participation, which has social impacts by excluding certain groups, and economic impacts by decreasing the diversity and richness of data which, in turn, can lead to less informed tourism policy decisions and less inclusive practices [146,147].

- Technical and economic challenges: Technical challenges can translate into direct economic impacts, such as additional costs to address vulnerabilities and maintain infrastructure. These challenges can also stall innovation and thus limit economic growth and job creation in the tourism sector. In addition, pressure on financial resources can divert investment from other critical areas, such as environmental protection and social development [117,148,149,150].

- Socio-environmental and ethical concerns: Socio-environmental and ethical impacts reflect the wider responsibility of the data space. Sustainability challenges and complications in international cooperation may affect the tourism sector’s ability to adapt to global environmental regulations. Ethical issues in data management have profound social implications, such as privacy and fairness. In addition, the environmental impact of data infrastructure and associated energy must be considered and minimised to align with sustainable tourism objectives [128,142].

6.5. Response

- Development and skill enhancement: Training and awareness raising are key to empowering tourism professionals to manage data effectively. These strategies ensure that staff are up to date with the skills needed to make the most of the data space, directly impacting quality and innovation within the sector.

- Infrastructure and technology improvement: Maintaining and upgrading the technology infrastructure is vital to support data’s increasing amount and complexity. Resilience and sustainability are critical to ensure the tourism data space is durable and environmentally responsible.

- Regulatory and ethical frameworks: Regulatory and ethical frameworks set the rules of the game, ensuring privacy, security, and accessibility of data. They are fundamental to maintaining user trust and ensuring ethical and equitable use of information.

- Engagement and inclusivity: Encouraging the participation of all stakeholders and ensuring equitable data representation are important steps in making the data space truly inclusive and representative, which enriches tourism analysis and decision-making.

- Innovation and development support: Innovation and integration are crucial to maintaining the tourism sector’s competitiveness. Supporting innovation through incentives and international cooperation opens new opportunities and enhances global interoperability.

- Monitoring and continuous improvement: Monitoring and feedback mechanisms allow for constant data space review and improvement. This ensures the system adapts and evolves according to sector needs and user expectations.

- Financial and resource management: Sound financial management is necessary to ensure sufficient resources for the data space’s construction, maintenance and enhancement. Sustainable financing models are crucial for the long-term viability of the tourism data space.

7. Overview

8. Discussion and Conclusions

- Economic: supporting innovation and ensuring that data spaces benefit not only large corporations, but also SMEs and other key players in the sector [155].

- Governance: creating an organizational culture and governance system that fosters data management transparency, ethics, and accountability [159].

- Technological: addressing the technological challenges in creating and maintaining robust, secure, and efficient data spaces. This includes the development of advanced algorithms, data processing capabilities, and cybersecurity measures to manage and protect the vast amounts of data generated in the tourism sector. It is essential to stay ahead in technological innovations to ensure the data spaces are not only functional, but also ahead of potential digital threats and challenges [160,161,162].

- -

- Drivers and pressures: The drivers behind the creation of these data spaces include the digitisation of the tourism sector, the need for personalisation and the growing demand for sustainability [97]. However, these drivers are exerting pressure on the data ecosystem, leading to challenges such as information overload and heterogeneity of sources.

- -

- Status and impact: While efforts to establish integrated and high-quality data spaces exist, the current state presents challenges. These include declining data quality and declining user trust due to privacy concerns. In addition, uneven geographical representation and interoperability challenges act as constraints, limiting the true potential of a unified European data market.

- -

- Responses: Steps are being taken to address these issues, with examples being data protection policies, public participation strategies and feedback mechanisms. However, despite these efforts, the ecosystem still exhibits notable gaps.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights, 2019 Edition. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/publication/international-tourism-highlights-2019-edition (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Saboori, B.; Ghader, Z.; Soleymani, A. A revised perspective on tourism-economic growth nexus, exploring tourism market diversification. Tour. Econ. 2022, 29, 1812–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Tourism development and sustainable well-being: A Beyond GDP perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 31, 2399–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, S.P.R.; Venkatraman, R.; Venkatraman, S. A Thematic Travel Recommendation System Using an Augmented Big Data Analytical Model. Technologies 2023, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Kumar, S.; Sureka, R.; Gaur, V.; Cobanoglu, C. Editorial: The Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology (JHTT): A retrospective review using bibliometric analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.Y.; Ma, F.C. An essay on the differences and linkages between data science and information science. Data Inf. Manag. 2023, 7, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R. Digital economy drives tourism development—Empirical evidence based on the UK. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2023, 36, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciarini, C.; Cappa, F.; Boccardelli, P.; Oriani, R. How can organizations leverage big data to innovate their business models? A systematic literature review. Technovation 2023, 123, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Mele, G.; Ndou, V.; Secundo, G. Creating value from Social Big Data: Implications for Smart Tourism Destinations. Inf. Process. Manag. 2018, 54, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, L. Big data in tourism research: A literature review. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Chan, J.H.; Qi, X. Big data in action: An overview of big data studies in tourism and hospitality literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Priporas, C.V.; Stylos, N. ‘You will like it!’ using open data to predict tourists’ response to a tourist attraction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Priporas, C.V.; Stylos, N.; Dennis, C. Facilitating tourists’ decision making through open data analyses: A novel recommender system. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Cui, Y.; Liu, E.N.X.U.A.N.; Young, J.; Polly, Y.; Sun, W.; Shen, H. Construction and Design of a Smart Tourism Model Based on Big Data Technologies. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 1120541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Data Governance Act. (2020, November 25). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on European Data Governance (Data Governance Act). EUR-Lex—52020PC0767. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022R0868 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Data Space Support Centre. Data Space Suport Center. 2023. Available online: https://dssc.eu/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- EU. European Data Space for Tourism (DATES). DATES Project. 2023. Available online: https://www.tourismdataspace-csa.eu/ (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- EU. Tourism Data Space (DSFT). 2023. Available online: https://dsft.modul.ac.at/about/ (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- European Commission. Towards a Common European Tourism Data Space: Boosting data sharing and innovation across the tourism ecosystem (2023/C 263/01). 2023, pp. 1–13. Available online: https://www.europeansources.info/record/towards-a-common-european-tourism-data-space-boosting-data-sharing-and-innovation-across-the-tourism-ecosystem/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Hammond, A.L.; Institute, W.R. Environmental Indicators: A Systematic Approach to Measuring and Reporting on Environmental Policy Performance in the Context of Sustainable Development; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Smeets, E.; Weterings, R. Environmental Indicators: Typology and Overview; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gari, S.R.; Newton, A.; Icely, J.D. A review of the application and evolution of the DPSIR framework with an emphasis on coastal social-ecological systems. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 103, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiner, S.; Orchiston, C.; Higham, J. Resilience and sustainability: A complementary relationship? Towards a practical conceptual model for the sustainability–resilience nexus in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1385–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Camargo, B.A. Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the Just Destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodko, G.W. Economics of New Pragmatism in Contemporary Society: Identity, Aims, Method. Polish Sociol. Rev. 2021, 216, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soare, I.; Virlanuta, F.-O.; Sorcaru, I.-A.; Manea, L.-D.; Muntean, M.-C.; Nistor, R. Territorial Cohesion and Competitiveness in Tourism Development in Romania. Ann. Dunarea Jos Univ. Galati. Fascicle I Econ. Appl. Inform. 2019, 25, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. In Creating Smarter Cities; Routlege: London, UK, 2013; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart tourism destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014, Proceedings of the International Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 21–24 January 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, M.; Höpken, W.; Lexhagen, M. Big data analytics for knowledge generation in tourism destinations. A case from Sweden. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. European Data Strategy. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0066 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- EU. Blue Print. Tourism Data Space. 2023. Available online: https://www.tourismdataspace-csa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/DRAFT-BLUEPRINT-Tourism-Data-Space-1-1.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Otto, B.; Hompel, M. Designing Data Spaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, E. Data Spaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, P.; Niebel, C.; Reiberg, A. What is a Data Space? Definition of the concept Data Space. 2022. Available online: https://gaia-x-hub.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/White_Paper_Definition_Dataspace_EN.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Li, W.; Quinn, P. Computer Law & Security Review: The International Journal of Technology Law and Practice The European Health Data Space: An expanded right to data portability? Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2024, 52, 105913. [Google Scholar]

- Marelli, L.; Stevens, M.; Sharon, T.; Van Hoyweghen, I.; Boeckhout, M.; Colussi, I.; Degelsegger-Márquez, A.; El-Sayed, S.; Hoeyer, K.; van Kessel, R.; et al. The European health data space: Too big to succeed? Health Policy 2023, 135, 2023–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kympouropoulos, S. Real World Evidence: Methodological issues and opportunities from the European Health Data Space. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2023, 23, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus, M.; Loureiro, M.; Fernandes, A.R.; Oliveira, M.; Cruz-Correia, R. Implementation Status of the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Health Data Space in Portugal: Are We Ready for It? Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2023, 302, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos, K.; Weber, M.; Trautner, T.; Manns, M.; Nikolakis, N.; Weigold, M.; Engel, B. An industrial data-spaces framework for resilient manufacturing value chains. Procedia CIRP 2023, 116, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, B.; Monsefi, A.K. Smart and collaborative industrial IoT: A federated learning and data space approach. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2023, 9, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, C.; Balland, P.-A.; Kakderi, C.; Provenzano, V. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 639 New Metropolitan Perspectives Transition with Resilience for Evolutionary Development. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 639. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, D.; Antonio, F.; Fiore, S.; Nassisi, P.; Aloisio, G. A Data Space for Climate Science in the European Open Science Cloud. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2023, 25, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, F.; Sutschet, G.; Stojanovic, L.; Uslaender, T. On the Role of Digital Twins in Data Spaces. Sensors 2023, 23, 7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomp, A.; Jansen, M.; Berg, H.; Meisen, T. SPACE-DS: Towards a Circular Economy Data Space. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 1500–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, P. Data Driven Smart Cities and Data Spaces; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 639. [Google Scholar]

- Usmani, A.; Khan, M.J.; Breslin, J.G.; Curry, E. Towards Multimodal Knowledge Graphs for Data Spaces. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 1494–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, T.; Pomp, A.; Meisen, T. Towards a Data Space for Interoperability of Analytic Provenance. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 1502–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettore, P.H.L.; Zissner, P.; Alkhowaiter, M.; Zou, C.; Sevenich, P. Military Data Space: Challenges, Opportunities, and Use Cases. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šestak, M.; Copot, D. Towards Trusted Data Sharing and Exchange in Agro-Food Supply Chains: Design Principles for Agricultural Data Spaces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, J.; Camiciotti, L.; Cheinasso, F.; Olivero, A.; Risso, F. Enabling Compute and Data Sovereignty with Infrastructure-Level Data Spaces. In Proceedings of the 3rd Eclipse Security, AI, Architecture and Modelling Conference on Cloud to Edge Continuum, Ludwigsburg, Germany, 17 October 2023; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer Zum Felde, H.; Kollenstart, M.; Bellebaum, T.; Dalmolen, S.; Brost, G. Extending Actor Models in Data Spaces. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023; Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023, pp. 1447–1451. [CrossRef]

- Terzis, P.; Santamaria Echeverria, O.E. Interoperability and governance in the European Health Data Space regulation. Med. Law Int. 2023, 23, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F. A Single European Data Space and Data Act for the Digital Single Market: On Datafication and the Viability of a Psd2-Like Access Regime for the Platform Economy. Eur. J. Leg. Stud. 2022, 14, 173–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janev, V.; Vidal, M.E.; Endris, K.; Pujic, D.; Machinery, A.C. Managing Knowledge in Energy Data Spaces. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; Univ Belgrade, Mihajlo Pupin Inst: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Solmaz, G.; Cirillo, F.; Fuerst, J.; Jacobs, T.; Bauer, M.; Kovacs, E.; Ramon Santana, J.; Sanchez, L.; Machinery, A.C. Enabling data spaces: Existing developments and challenges. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Data Economy, Rome, Italy, 9 December 2022; pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Data Sharing Initiatives Survey. DATES Project. 2023. Available online: https://www.tourismdataspace-csa.eu/data-sharing-initiatives/ (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- EU. Data Sharing Initiatives Inventory. DATES Project. European Data Space for Tourism. Deliverable D.2.1. 2023. Available online: https://www.tourismdataspace-csa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DATES-D2.1-Data-sharing-initiatives-inventory-DEF.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Tscherning, K.; Helming, K.; Krippner, B.; Sieber, S.; Paloma, S.G.y. Does research applying the DPSIR framework support decision making? Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Luo, Z.; Hu, X.; Nan, Y.; Wei, A. A DPSIR Framework to Evaluate and Predict the Development of Prefabricated Buildings: A Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, B.; Anderberg, S.; Olsson, L. Structuring problems in sustainability science: The multi-level DPSIR framework. Geoforum 2010, 41, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasrotia, A.; Gangotia, A. Smart cities to smart tourism destinations: A review paper. Tour. Intell. Smartness 2018, 1, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A.; Femenia-Serra, F.; Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Vera-Rebollo, J.F. Smart city and smart destination planning: Examining instruments and perceived impacts in Spain. Cities 2023, 137, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qonita, M.; Giyarsih, S.R. Smart city assessment using the Boyd Cohen smart city wheel in Salatiga, Indonesia. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AENOR UNE 178501; Sistema de Gestión de los Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes. Requisitos. 2016. Available online: https://www.une.org/la-asociacion/sala-de-informacion-une/noticias/une-178501-sistema-de-gestion-de-los-destinos-turisticos-inteligentes (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Mohammed, R.T.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Albahri, O.S.; Zaidan, A.A.; AlSattar, H.A.; Aickelin, U.; Albahri, A.S.; Zaidan, B.B.; Ismail, A.R.; Malik, R.Q. A decision modeling approach for smart e-tourism data management applications based on spherical fuzzy rough environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 143, 110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Crespo, P.; Bermudez-Edo, M.; Garrido, J.L. Smart tourism in Villages: Challenges and the Alpujarra Case Study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 204, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitro, N.; Krommyda, M.; Amditis, A. Smart Tags: IoT Sensors for Monitoring the Micro-Climate of Cultural Heritage Monuments. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, A.; Ros, D.F.; Gómez-Oliva, A.; Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Jara, A.J.; Laborda, J.; Mazón, J.N.; Perles, A. Crowd Monitoring in Smart Destinations Based on GDPR-Ready Opportunistic RF Scanning and Classification of WiFi Devices to Identify and Classify Visitors’ Origins. Electronics 2022, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, A.; Weber, K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Shi, W. Categorisation of cultural tourism attractions by tourist preference using location-based social network data: The case of Central, Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2022, 90, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangachena, J.R.; Geerts, S.; Pickering, C.M. Spatial and temporal patterns in wildlife tourism encounters and how people feel about them based on social media data from South Africa. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 44, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Park, J.; Hu, M. Tourism demand forecasting with online news data mining. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, A.; Pons, F.M.E.; Angelini, G.; Ranieri, E. Big data from dynamic pricing: A smart approach to tourism demand forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Qian, Y.; Wang, S. Forecasting Chinese cruise tourism demand with big data: An optimized machine learning approach. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Wankhede, V.A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Huisingh, D. Big data analytics and sustainable tourism: A comprehensive review and network based analysis for potential future research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birenboim, A.; Bulis, Y.; Omer, I. A typology of tourism mobility apps. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 48, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmücker, D.; Reif, J. Measuring tourism with big data? Empirical insights from comparing passive GPS data and passive mobile data. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Wang, X.K.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Peng, J.J. Customer purchase forecasting for online tourism: A data-driven method with multiplex behavior data. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, G.S.; Jeong, J.Y.; Lee, W.K. Social big data informs spatially explicit management options for national parks with high tourism pressures. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, F.; Altuntas, S.; Dereli, T. Social network analysis of tourism data: A case study of quarantine decisions in COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Qu, H.; Tsang, W.S.L.; Lam, C.W.R. The influence of smart tourism applications on perceived destination image and behavioral intention: The moderating role of information search behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelawat, N.; Jariyapongpaiboon, S.; Promjun, A.; Boonyarak, S.; Saengtabtim, K.; Laosunthara, A.; Yudha, A.K.; Tang, J. Twitter data sentiment analysis of tourism in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, T.; Uryu, S.; Yamano, H.; Tsuge, T.; Yamakita, T.; Shirayama, Y. Mobile phone network data reveal nationwide economic value of coastal tourism under climate change. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A.; Shakeri, M.; Choi, S.M. Personalized augmented reality based tourism system: Big data and user demographic contexts. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Ali, F. 20 years of research on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism context: A text-mining approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkul, E.; Kumlu, S.T. Augmented Reality Applications in Tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Tour. Res. 2019, 3, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B. Telecommunication and tourism development: An island perspective. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustacha, I.; Baños-Pino, J.F.; Del Valle, E. The role of technology in enhancing the tourism experience in smart destinations: A meta-analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 30, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, O.; Werthner, H. Harmonise: A step toward an interoperable e-tourism marketplace. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2005, 9, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, B. The evolution of data spaces. In Designing Data Spaces: The Ecosystem Approach to Competitive Advantage; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsev, A.; Minghini, M.; Tomas, R.; Cetl, V.; Lutz, M. From spatial data infrastructures to data spaces—A technological perspective on the evolution of European SDIs. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC, O.E. Travel and Tourism Share of Gdp in the EU by Country. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1228395/travel-and-tourism-share-of-gdp-in-the-eu-by-country (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Kubacka, M.; Bródka, S.; Macias, A. Selecting agri-environmental indicators for monitoring and assessment of environmental management in the example of landscape parks in Poland. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivčević, S.; Petrić, L.; Mandić, A. Sustainability of tourism development in the Mediterranean-Interregional similarities and differences. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Bichler, B.F. Innovation research in tourism: Research streams and actions for the future. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardak, S.; Dzhyndzhoian, V.; Samoilenko, A. Global innovations in tourism. Innov. Mark. 2016, 12, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nuenen, T.; Scarles, C. Advancements in technology and digital media in tourism. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, C.; Turner, L.W. Regional economic development and tourism: A literature review to highlight future directions for regional tourism research. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A sustainable tourism policy research review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pforr, C. Tourism and public policy. Handb. Bus. Public Policy 2021, 12, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmoun, M.; Baeshen, Y. Marketing Tourism in the Digital Era and Determinants of Success Factors Influencing Tourist Destinations Preferences. Asia-Pac. Manag. Account. J. 2021, 16, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, S.; Seetaram, N. Measuring the Effect of Revealed Cultural Preferences on Tourism Exports. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Fleischer, A. The relationship between cultural characteristics and preference for active vs. Passive tourist activities. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2005, 12, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviolidis, N.M.; Cook, D.; Davíðsdóttir, B.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Ólafsson, S. Challenges of national measurement of environmental sustainability in tourism. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J.; Espinosa-Pulido, J.A. Does environmental sustainability contribute to tourism growth? An analysis at the country level. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, M.; Dodds, R.; Walsh, P. Developing a Scalable Data-Driven Decision-Making Tool for Smart Destination Management. In Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally; TTRA: Lapeer, MI, USA, 2022; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Qiao, X.; Chen, X. A Big Data based Decision Framework for Public Management and Service in Tourism. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security Companion (QRS-C), Macau, China, 11–14 December 2020; pp. 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengio, B.; Olakunle, I.; Kajtazi, M.; Emruli, B. Capitalizing on Data-Driven Decision-Making Culture for Tourism Management. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9065393&fileOId=9065396 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Islam, M.W.; Ruhanen, L.; Ritchie, B.W. Adaptive co-management: A novel approach to tourism destination governance? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.J.; Actis, K.; Fu, J.S. Nonprofits’ external stakeholder engagement and collaboration for innovation: A typology and comparative analysis. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2023, 33, 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Sharples, M.; Foster, C. Stakeholder engagement in the design of scenarios of technology-enhanced tourism services. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, C.; Pandolfo, G.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Siciliano, R. Mining big data in tourism. Qual. Quant. 2020, 54, 1655–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, C.; Rula, A. From Data Quality to Big Data Quality: A Data Integration Scenario. 2021. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/From-Data-Quality-to-Big-Data-Quality%3A-A-Data-Batini-Rula/4ef477c73f6fe1586e3e6155b29ef55bb330d410 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Samara, D.; Magnisalis, I.; Peristeras, V. Artificial intelligence and big data in tourism: A systematic literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020, 11, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, I.; Neuhofer, I.O.; Dogru, T.; Oztel, A.; Searcy, C.; Yorulmaz, A.C. Improving sustainability in the tourism industry through blockchain technology: Challenges and opportunities. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, J.; Pierson, J. The right to the city and data protection for developing citizen-centric digital cities. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 24, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, S. Protection of personal data in the tourism sector. Menadzment u Hotel. i Tur. 2023, 11, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Gómez, A.; Ruiz-Palomo, D.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; García-Revilla, M.R. Sustainable tourism development and economic growth: Bibliometric review and analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Matesanz Gómez, D.; Segarra, V. On the empirical relationship between tourism and economic growth. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Park, O.J.; Yun, S.; Yun, H. What makes tourists feel negatively about tourism destinations? Application of hybrid text mining methodology to smart destination management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 123, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoumas, A. Evaluating a standard for sustainable tourism through the lenses of local industry. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, C.C.; Laso, J.; Cristóbal, J.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Albertí, J.; Fullana, M.; Herrero, Á.; Margallo, M.; Aldaco, R. Tourism under a life cycle thinking approach: A review of perspectives and new challenges for the tourism sector in the last decades. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yallop, A.C.; Gică, O.A.; Moisescu, O.I.; Coroș, M.M.; Séraphin, H. The digital traveller: Implications for data ethics and data governance in tourism and hospitality. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian Fereidouni, M.; Kawa, A. Dark Side of Digital Transformation in Tourism BT–Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Nguyen, N.T., Gaol, F.L., Hong, T.-P., Trawiński, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 510–518. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, F. Cooperation, hotspots and prospects for tourism environmental impact assessments. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, T.P.; Leonel, J.; Imperador, A.M. A systemic environmental impact assessment on tourism in island and coastal ecosystems. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Economic Value of Tourism Through Human Capital Gains. J. Travel Res. 2022, 62, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guo, Y. Revisiting resources extraction perspective in determining the tourism industry: Globalisation and human capital for next-11 economies. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Ridderstaat, J.; Bąk, M.; Zientara, P. Tourism specialization, economic growth, human development and transition economies: The case of Poland. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhanvar, A.; Çiftçioğlu, S.; Javid, E. Another look at tourism—Economic development nexus. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommandru, A.; Espinoza-Maguiña, M.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Ray, S.; Naved, M.; Guzman-Avalos, M. Role of tourism and hospitality business in economic development. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 2901–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytiäinen, K.; Kolehmainen, L.; Amelung, B.; Kok, K.; Lonkila, K.M.; Malve, O.; Similä, J.; Sokero, M.; Zandersen, M. Extending the shared socioeconomic pathways for adaptation planning of blue tourism. Futures 2022, 137, 102917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Peng, H. Do socio-economic factors matter? A comprehensive evaluation of tourism eco-efficiency determinants in China based on the Geographical Detector Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenders, G.; Ferrer-Rosell, B. Compositional data analysis in tourism: Review and future directions. Tour. Anal. 2020, 25, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Phi, G.; Mahadevan, R.; Popescu, E.S. Digitalisation in Tourism. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/33163/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Aref, F.; Redzuan, M. Community Leaders’ Perceptions toward Tourism Impacts and Level of Building Community Capacity in Tourism Development. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 2, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchon, F.; Rawat, K. Rural Areas of ASEAN and Tourism Services, a Field for Innovative Solutions. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F. Designing tourism governance: The role of local residents. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L. Big data or small data? A methodological review of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, T.; Wozniak, D. The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Johnson, R.L. The economic values of tourism’s social impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Huang, H.; Choi, H.; Bilgihan, A. Building organizational resilience with digital transformation. J. Serv. Manag. 2023, 34, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsari, I. Exploring the nexus between sustainable tourism governance, resilience and complexity research. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Islam, J.U. Tourism-based customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.W.; Teng, H.Y.; Chen, C.Y. Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojeghan, S.B.; Esfangareh, A.N. Digital economy and tourism impacts, influences and challenges. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panai, E. A Cyber Security Framework for Independent Hotels. In Proceedings of the 4th EATSA-FRANCE 2018, Challenges of Tourism Development, Dijon, France, 18 June–12 May 2018; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Solakis, K.; Katsoni, V.; Mahmoud, A.B.; Grigoriou, N. Factors affecting value co-creation through artificial intelligence in tourism: A general literature review. J. Tour. Futur. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuno, S.; Bruns, L.; Tcholtchev, N.; Laemmel, P.; Schieferdecker, I. Data Governance and Sovereignty in Urban Data Spaces Based on Standardized ICT Reference Architectures. DATA 2019, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Schroeder, A. A systematic literature review of data privacy and security research on smart tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futur. 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.R. Conceptualising tourism transport: Inequality and externality issues. J. Transp. Geogr. 1999, 7, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.H.; Xie, C.W.; Morrison, A.M. Tourism Crises and Impacts on Destinations: A Systematic Review of the Tourism and Hospitality Literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 667–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badulescu, D.; Simut, R.; Mester, I.; Dzitac, S.; Sehleanu, M.; Bac, D.P.; Badulescu, A. Do economic growth and environment quality contribute to tourism development in eu countries? A panel data analysis. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 1509–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkuş-Öztürk, H.; Eraydin, A. Environmental governance for sustainable tourism development: Collaborative networks and organisation building in the Antalya tourism region. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, C.; Borja, A.; Uyarra, M.C.; Pouso, S. Surfing the waves: Environmental and socio-economic aspects of surf tourism and recreation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Sustainable tourism governance: Local or global? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadian, E.; Feitosa, D.; Zwitter, A. A systematic literature review on the use of big data for sustainable tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1711–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănescu, C.; Boboc, C.; Ghiță, S.; Vasile, V. Tourism in Digital Era. In Proceedings of the 7th BASIQ International Conference on New Trends in Sustainable Business and Consumption, Foggia, Italy, 3–5 June 2021; pp. 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Rocha, C.A.; Yamanaka, F.I.; da Silva, E.L. Information technology and communication applied to tourism: Trends and possibilities. Navus-Rev. Gest. E Tecnol. 2016, 6, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

| Factors | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Drivers: | They refer to the social, economic or technological factors that initiate the demand for tourism data spaces. | E.g., increased demand for tourism information to inform supply planning decisions, sustainable tourism growth and personalised experiences, and a boom in international mobility and experiential tourism. |

| 2. Pressures: | Direct results of the drivers. | E.g., an increase in mobile applications that facilitate hotel/restaurant booking, the development of interactive platforms for the design of personalised itineraries, and an increase in the creation of collaborative databases where tourists share their experiences. |

| 3. Status: | They describe the current condition or state of the data ecosystem. | E.g., increase in mobile phone usage and a growing level of digital literacy in the population; consolidated presence of large online booking platforms; existence of fragmented data networks and lack of standardisation in tourism information. |

| 4. Impact: | Effects or outcomes resulting from pressures on the state. | E.g., cybersecurity breaches, social changes due to the use of smartphones or changes in employment due to automation, overloading of popular tourist destinations due to easy access to information, and the emergence of new business models in the tourism sector due to data analytics. |

| 5. Response: | Actions taken or to be taken to address impacts. | E.g., training programmes on the use of smart devices and reinforcement of cybersecurity measures; implementation of unified standards for the exchange of tourism data; creation of sustainability policies based on data analysis to prevent overtourism. |

| Code of Conduct on data sharing in tourism https://etc-corporate.org/uploads/2023/03/Code-of-Conduct-on-Data-Sharing-in-Tourism_Final.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Passenger Rights Directive https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/48/los-derechos-de-los-pasajeros (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Package Travel Directive 2015/2302 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32015L2302 (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Directive on patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare 2011/24/EU https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/En/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32011L0024 (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Consumer Rights Directive 2011/83/EU https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/En/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32011L0083 (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005/29/EU https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/En/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32005L0029 (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Regulation on fairness in relations between trading platforms 2019/1150/EU https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R1150 (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Ecolabel Directive 66/2010 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32010R0066 (accessed on 12 November 2023) |

| Type of Organisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Role: Producer/Consumer | Large Company | NGO | Public Administration | SME | Start-Up Company | Other | Grand Total |

| Both | 4.7 | 16.5 | 23.6 | 12.3 | 1.9 | 11.8 | 70.8 |

| Data consumer | 1.4 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 4.2 | 18.4 |

| Data producer | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 10.8 |

| Grand total | 6.6 | 23.1 | 29.2 | 16.0 | 5.2 | 19.8 | 100.0 |

| Function of Organisation | Data Consumer | Data Producer | Both | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business development | 1.4 | 0.9 | 6.6 | 9.0 |

| Data analytics | 3.3 | 1.4 | 15.6 | 20.3 |

| General management | 4.7 | 4.7 | 16.0 | 25.5 |

| Marketing | 0.9 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 5.7 |

| Operations | 0.5 | 0.5 | 6.6 | 7.5 |

| Other | 6.6 | 1.9 | 18.4 | 26.9 |

| Public relations | 0.9 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 4.7 |

| Purchasing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Grand total | 18.4 | 10.8 | 70.8 | 100.0 |

| User-Generated Data | Transactional Data | Data by Device |

| Direct Data Sources Surveys and Direct Collections Community-collected information on the accessibility of tourist sites -Social Media Platforms Instagram Photos, Facebook Comments, TripAdvisor Reviews, Experiences listed on Get Your Guide Social media reviews Customer posts and reviews on social media Text on social networks (feelings, evaluations), photos, and videos Social media Website and Platform Specific Information Photo and video bank Visitor reviews and opinions on booking portals, social networks, etc. Tourist Information Number of tourists per year and location Identity, payment, preferences Information Formats Textual information and photos/videos Textual information (online reviews, posts, comments on social media, etc.) Textual information and photos/videos. | Reservations and Capacity Reservation details, capacity and number of nights. Search and bookings on platforms such as Booking.com, TripAdvisor and other hotel engines. Commercial Transactions and Payments Business operational data. Credit card transactions: payments in shops, online bookings and purchases. Sales trends and analysis, including flight bookings. Marketing and Advertising Data Data related to campaigns, websites, social media, and marketing analytics. Government and Financial Sector Data Information provided by governments, banking and telecommunications sectors. Tourism Industry Metrics and Ratios Metrics include hotel occupancy, revenue, rooms sold, average price, and RevPar, among others. Platforms and Analysis Tools Tools and platforms such as ISTAT, SIAE, optimizadata.com, Biontrend and social media analytics | Location Data GPS, Mobile Roaming, Movement tracking (including weather and Wi-Fi). Device Data IoT devices, Bluetooth mobile phones, Personal mobile phones. Interaction and Behavioural Data Engagement in digital campaigns and websites, number of visitors, language, interactions, likes and subscriptions. Environmental and Sensor Information Weather data, vehicle traffic, traffic flow, environmental data, and visitor counts in car parks. Timely and Event Information Points of interest such as hotels, restaurants, and tours. Commercial and Consumer Data Types of tourists, mobility, behaviour, use of water and fuel, amount of litter in public. |

| Theme | Subtheme | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ecotourism and Sustainability | Ecological Accommodation Spend | Expenditure on green hotels and eco-friendly lodgings |

| Eco-friendly Activity Spend | Spending on environmentally friendly tourist activities | |

| Tourist Carbon Footprint | Estimated CO2 emissions from tourists | |

| Preferences of tourists and Behaviour | Vegan Dietary Preferences | Tourist preferences for vegan dining options |

| Night-time Tour Activities | Popularity of night-time tour activities | |

| Digital Museum Visits | Count of online museum and exhibit visits | |

| Adventure Sport Interest | Interest in high-risk or adventure sports while touring | |

| Underwater Tourism Data | Interest in and visits to underwater attractions | |

| Elderly Specific Activities | Tourist activities preferred by the elderly | |

| Space Tourism Interest | Interest in space-related tourist activities | |

| Solo Female Traveller Data | Insights on Solo Female Travellers | |

| Culinary Tourism Data | Interest in culinary experiences during travel | |

| Youth Hostel Bookings | Number of bookings in youth hostels | |

| Silent Retreats Data | Interest in retreats focusing on silence and meditation | |

| Adventure and Sports Tourism | Adventure Sport Interest | Interest in high-risk or adventure sports while touring |

| Cycling Tourism Trends | Popularity of cycling during tourist trips | |

| Cultural and Educational Tourism | Cultural Exchange Programs | Participation in local cultural exchange programs |

| Digital Museum Visits | Count of online museum and exhibit visits | |

| Inclusive Tourism | Inclusive Tourism for Disabilities | Data on tourism provisions for the differently abled |

| LGBTQ+ Friendly Places | Places popular among LGBTQ+ tourists | |

| Health and Wellness | Wellness and Spa Retreats | Popularity of wellness-focused retreats |

| Silent Retreats Data | Interest in retreats focusing on silence and meditation | |

| Specific Themes | Disaster-affected Tourism | Visits to areas affected by natural disasters |

| Space Tourism Interest | Interest in space-related tourist activities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ordóñez-Martínez, D.; Seguí-Pons, J.M.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Conceptual Framework and Prospective Analysis of EU Tourism Data Spaces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010371

Ordóñez-Martínez D, Seguí-Pons JM, Ruiz-Pérez M. Conceptual Framework and Prospective Analysis of EU Tourism Data Spaces. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010371

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrdóñez-Martínez, Dolores, Joana M. Seguí-Pons, and Maurici Ruiz-Pérez. 2024. "Conceptual Framework and Prospective Analysis of EU Tourism Data Spaces" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010371

APA StyleOrdóñez-Martínez, D., Seguí-Pons, J. M., & Ruiz-Pérez, M. (2024). Conceptual Framework and Prospective Analysis of EU Tourism Data Spaces. Sustainability, 16(1), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010371