A Responsive Approach for Designing Shared Urban Spaces in Tourist Villages

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Can the urban designer depend on the physical components of urban spaces without considering the psychological and sensory needs of their users?

- Do the needs of the target group affect the design and spatial formation of shared open space?

- What are the needs that must be considered in the design process of shared open spaces?

- What are the design criteria and considerations that have to be met in order to reach optimal design and promote the effectiveness of urban spaces?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourist Villages and Shared Urban Open Spaces

2.2. Social Sustainability and the Natural Environment

2.3. Relation between Humans and Their Environment

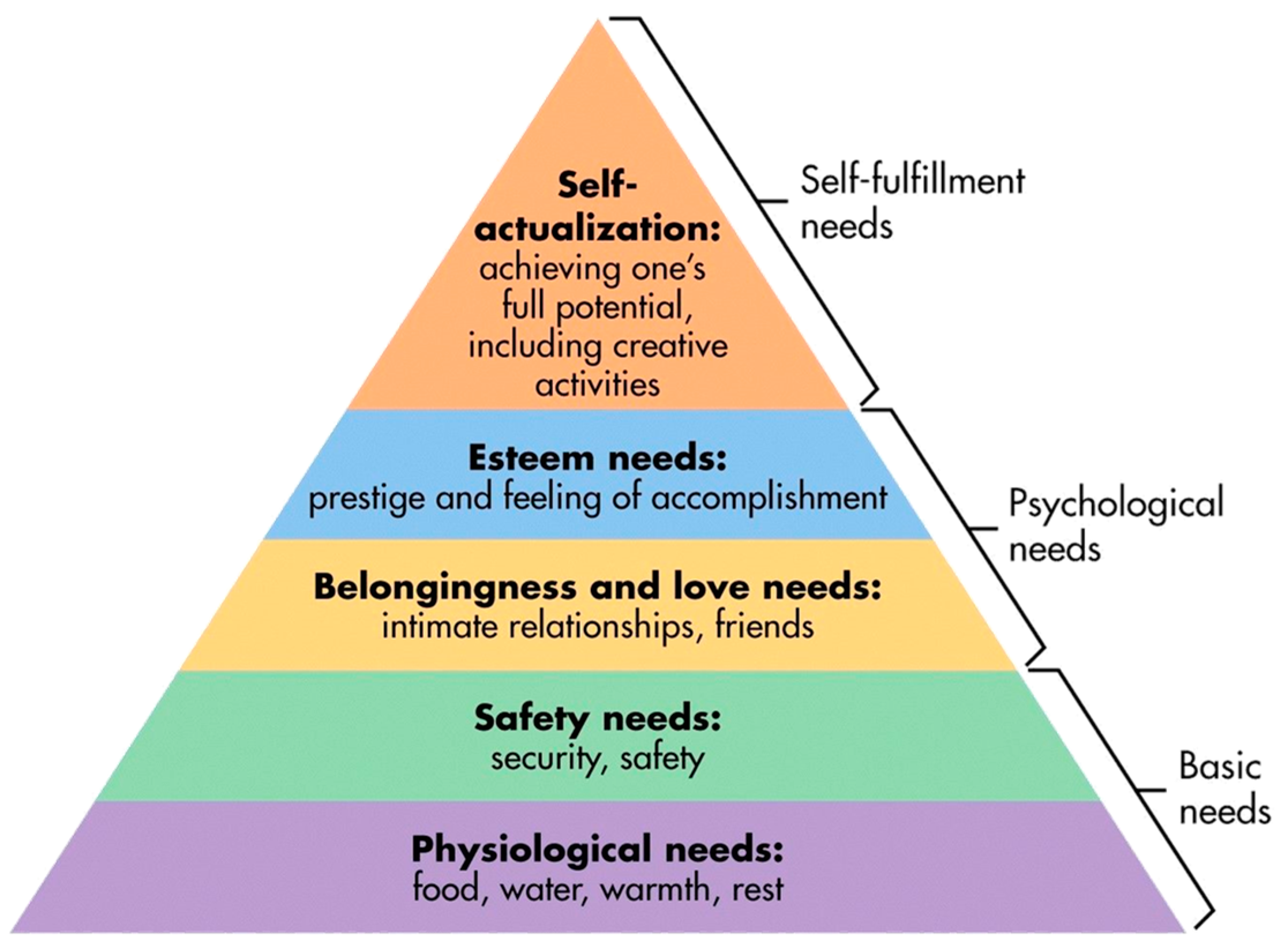

- Basic needs: These are physiological and functional needs or the primary requirements associated with inherent activities related to human survival, growth, health, and comfort for humans, such as hunger, thirst, etc., which are the lowest level.

- Supplementary and recreational (motivational) needs: These refer to psychological, social, and sensory needs related to self-realization and self-expression, which depend on the culture of a certain group of people. These needs start with security, safety, and stability needs and progress to self-realization and self-respect needs. This research paper will study motivational needs, which are divided into psychological and sensory needs, as well as social needs and functional needs.

2.4. Psychological and Sensory Needs in Shared Open Spaces in Tourist Villages

2.4.1. Integration with the Natural Environment

2.4.2. Security and Safety

2.4.3. Feeling of Distinction

2.5. Visual Needs in Shared Open Spaces in Tourist Villages

2.6. Social Needs in Shared Open Spaces in Tourist Villages

2.6.1. Social Interactions

2.6.2. Privacy

2.7. Functional Needs in Shared Open Spaces in Tourist Villages

2.7.1. Diversity of Activities

- Extended green areas that provide spaciousness and comfort to users looking at or going through them. These areas should be placed somewhere far from noise and disturbance.

- Kids’ play areas, where they can find all the entertainment activities they need and have fun. These areas must be secured and subject to the supervision of parents.

- Playground areas for adults should be located in faraway places and away from residential areas. These areas can be used for other purposes and activities during certain events.

2.7.2. Inclusiveness

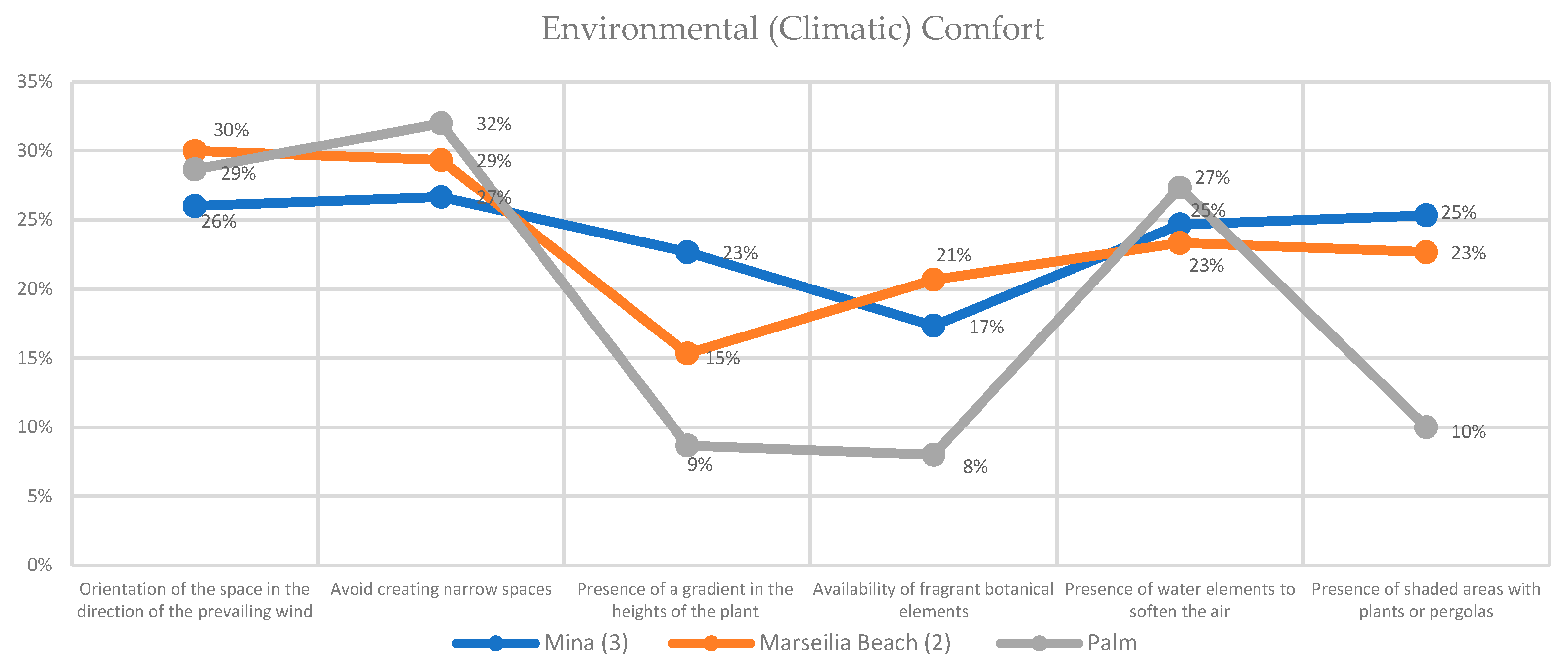

2.7.3. Environmental (Climatic) Comfort

2.8. Design Criteria for Shared Urban Spaces and The Impact of Human Needs on Them

- The urban space should be prepared for the use of individuals and meet the needs of most groups without any conflict.

- The location of the urban space should be clear and easily accessible.

- The urban space should provide an aesthetic environment that brings the users closer to nature and promotes the emotional aspects of humans.

- The urban space should provide a sense of safety and security for its users.

- The urban space should have the furnishing elements necessary to support existing activities and be characterized by ease of maintenance.

- The urban space should provide a physiologically comfortable environment for users.

- The urban space should contain elements that respect the human scale so that users can interact with such spaces.

- Creating a place for people: The urban space should provide comfort, safety, and attractiveness. In addition, the design and the space’s components should suit the different needs of the target groups to achieve urban quality.

- Enriching the existing place: The new development of any urban space must be compatible with the nature of the existing context and environment. This will create a distinctive personality in the urban space and strengthen the sense of beauty and distinction.

- Connectivity: A good urban space is always distinguished by its clear features and easy access to all its parts, so the urban designer should be aware of how to clarify the space’s features and the design criteria for all components and pathways in terms of dimensions, sizes, and positions, thus providing comfort and ease in dealing with the urban space.

- Appropriate use of landscape elements: A balance must be achieved between softscape and hardscape elements and maximum utilization of natural resources. The urban designer must be aware of the resources and capabilities available and adapt the environment according to the users’ needs.

- Mixed uses: The space is attractive and motivating for the user when it has the ability to meet all the needs of users without any conflict. This requires a degree of diversity in uses and forms that suit the requirements of each group of people. The success of the urban space in the mixing process is measured by its ability to generate different interactions between users.

- Investment management: This means the ability of the urban space to be economically feasible, through understanding of market needs, available capabilities, and determinants of economic aspects. One of the important parts of the design process is to identify appropriate implementation mechanisms and consider them to reduce the cost of maintenance.

- Design for change: This means that the urban space is able to develop and communicate with the changeable and diverse variables of the users’ needs over time, and thus ensure achievement of the sustainable development of the urban space. In order to achieve this requirement, the urban designer should design a flexible and permeable urban space. In addition, the urban designer should be able to divide the urban space into smaller areas based on their different natures and functions.

3. Materials and Methods

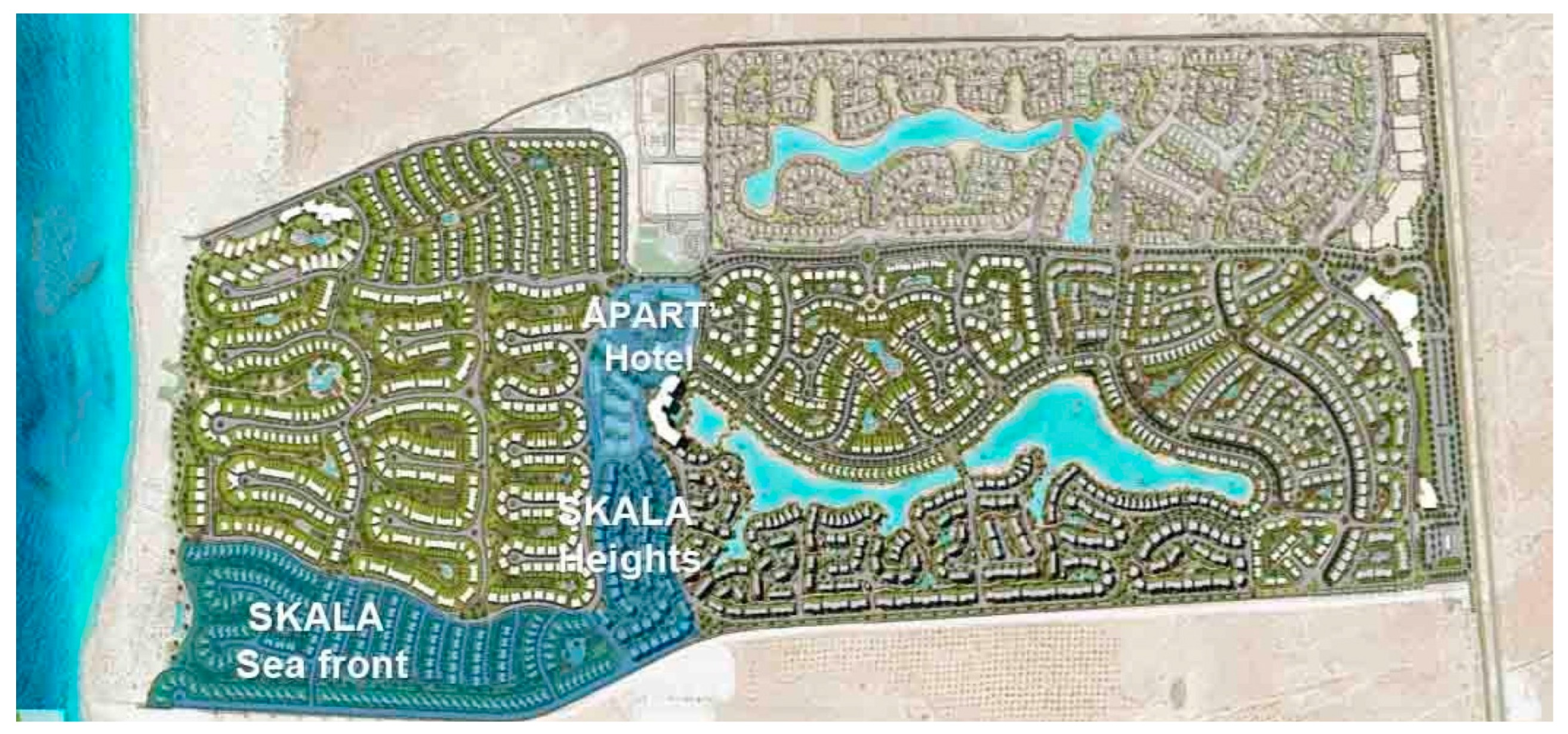

3.1. Research Gap and Sample Site and Criteria Selection

3.2. Research Methodology and Questionnaire Design

- Understanding fundamental urban design approaches and the related human role;

- Studying the different physical and moral needs of users;

- Highlighting the main design criteria and standards that must be adopted to reach an optimal design that satisfies the desires and preferences of the target group.

- Studying the nature and components of tourist villages to clarify the nature of design and planning and to present the urban fabric followed;

- Measuring the extent to which human needs are met through design criteria, spatial formation, and landscape elements;

- Studying users’ impressions of the process of urban design of shared urban spaces.

- Site visits to the villages during the summer vacation from June till mid-September. The researcher visited the villages three times during the study.

- Interviews in the three villages with the village manager, the security manager, and employees in several departments (Table 1).

- A data collection form the researcher prepared was used to monitor all components of the village and the available elements, in addition to study of the fabrics used.

- Users’ data, to determine the demographic characteristics of users in terms of age group, marital status, gender, and level of education.

- An evaluation table to measure the level of fulfilment of each need in the shared open spaces, where the users determine the availability and quality of the design criteria and its impact on their needs.

- An evaluation table to measure the impact of the spatial formation and landscape elements on humanitarian needs in order to find out the most important elements to fulfill the needs in future project development.

4. Results of User Demographic Characteristics and Site Investigation

- Gender: The percentage of males in the sample reached 38%, while for females the percentage was higher, reaching 62%. This high percentage is attributed to the issue that most of the males spend their week days working in the home city leaving their wives with their kids. They usually spend the weekends in the tourist village with their families.

- Age group: The age group of the sample varied to show the impact on needs, especially those related to the diversity of activities and inclusiveness, and the percentage of the group aged between 18–25 years was 32%; that from 26–40 years was 39%; that from 41–60 years was 22%; and, finally, the percentage of those over 60 decreased to 7%, which is considered a very low percentage.

- Marital status: The sample’s marital status varied between single and widowed, and the percentages were as follows: single 19%, widowed 3%, in a relationship 11%, married 20%, married with children 47%. Observation of these percentages reveals that the highest percentages were for married couples with children, who mostly come for enjoying the summer vacation and having fun, followed by married couples and singles who travel for relaxation and recreation.

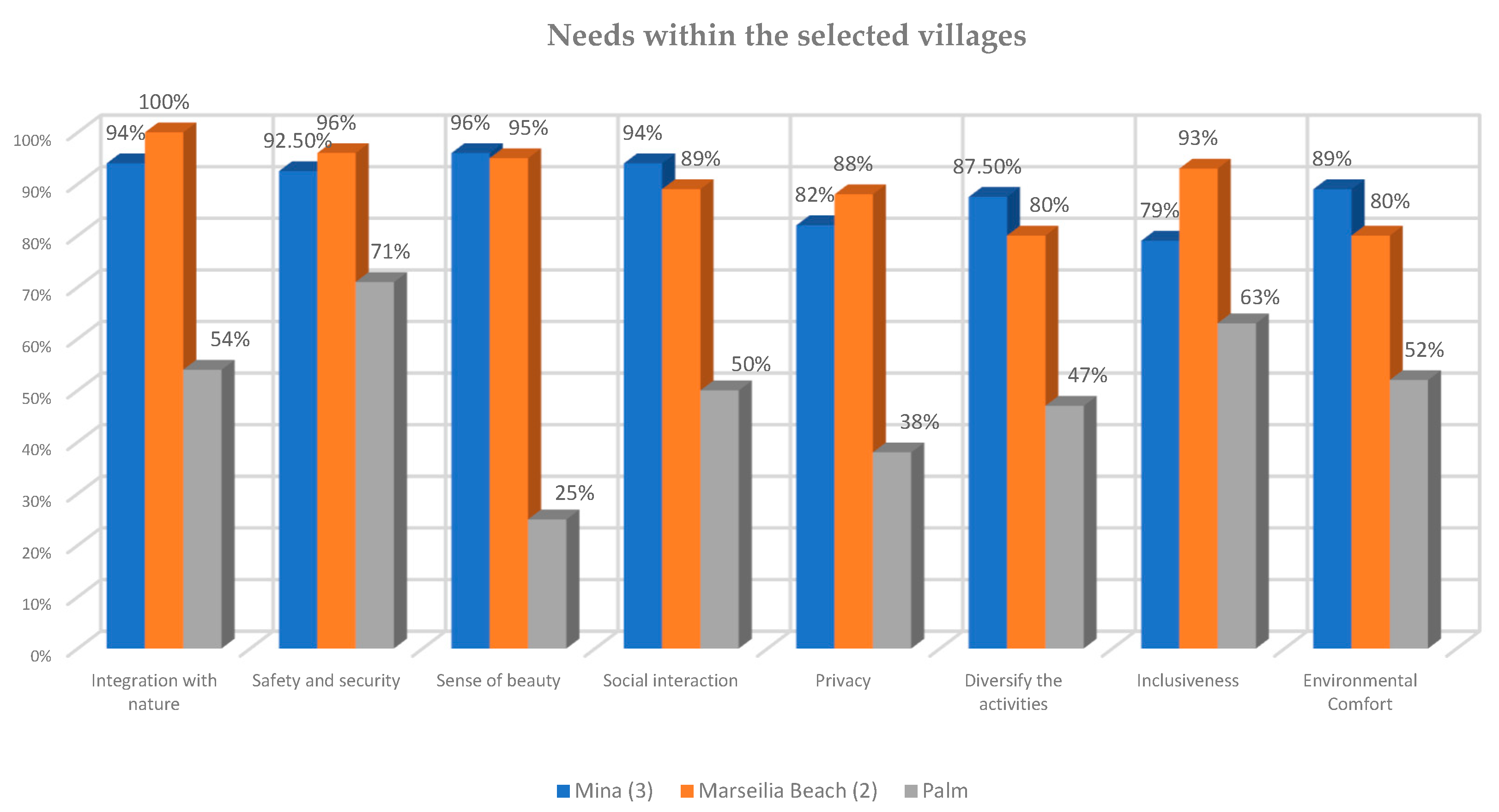

5. Discussion of Humanitarian Needs within the Shared Open Space

5.1. Psychological and Sensory Needs

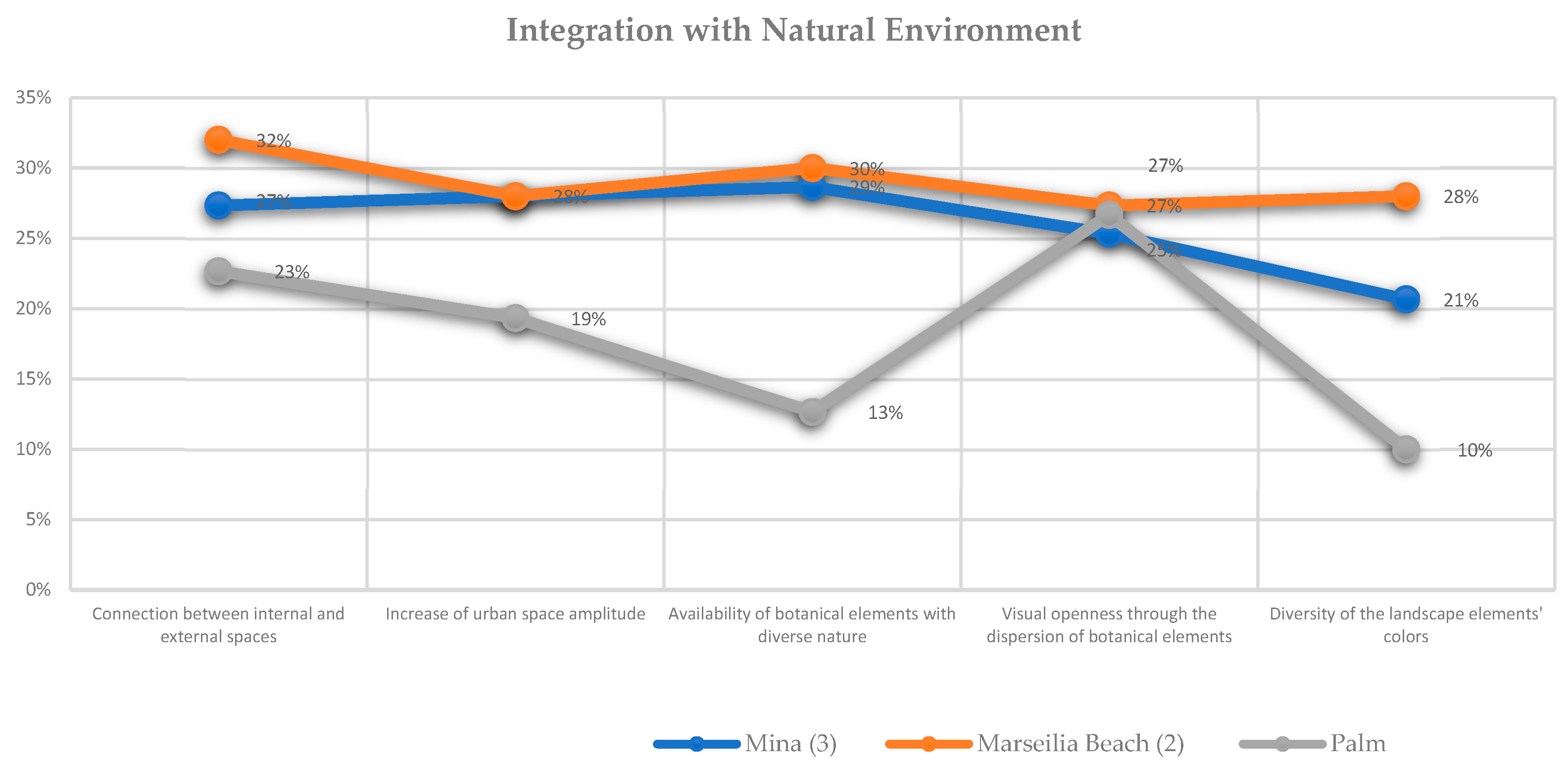

5.1.1. Integration with the Natural Environment

- The scale of the shared open space is relatively medium in Marseilia Beach (2) Village, while it is relatively large in Mina (3) Village. Both scales strengthen the sense of visual openness and support the feeling of continuity of internal spaces with external ones, especially for the ground floor units, where Marseilia Beach (2) reaches 32%, followed by Mina 2 at 27%.

- The availability, diversity, and good distribution of landscape elements inside the shared open spaces, in addition to the fact that many of these elements were natural or made from natural materials, such as:

- The availability of various types of seasonal plants, which vary with the change of seasons and have cheerful colors. This factor was achieved at 29% in Mina (3) and at 30% in Marseilia Beach (2).

- A fountain was placed as a focal point inside the space in Mina (3) Village, which is made of natural materials such as stones and wood (Figure 6).

- In Marseilia Beach (2) Village, although the urban designer used concrete paving, he covered them with natural colors and elements that gave a sense of being natural (Figure 7). Furthermore, he shaped the fences and the borders of the space in the forms of tree trunks. The average percentages for the diversity of landscape elements and their characteristics were 30% for the softscape elements and 28% for the others.

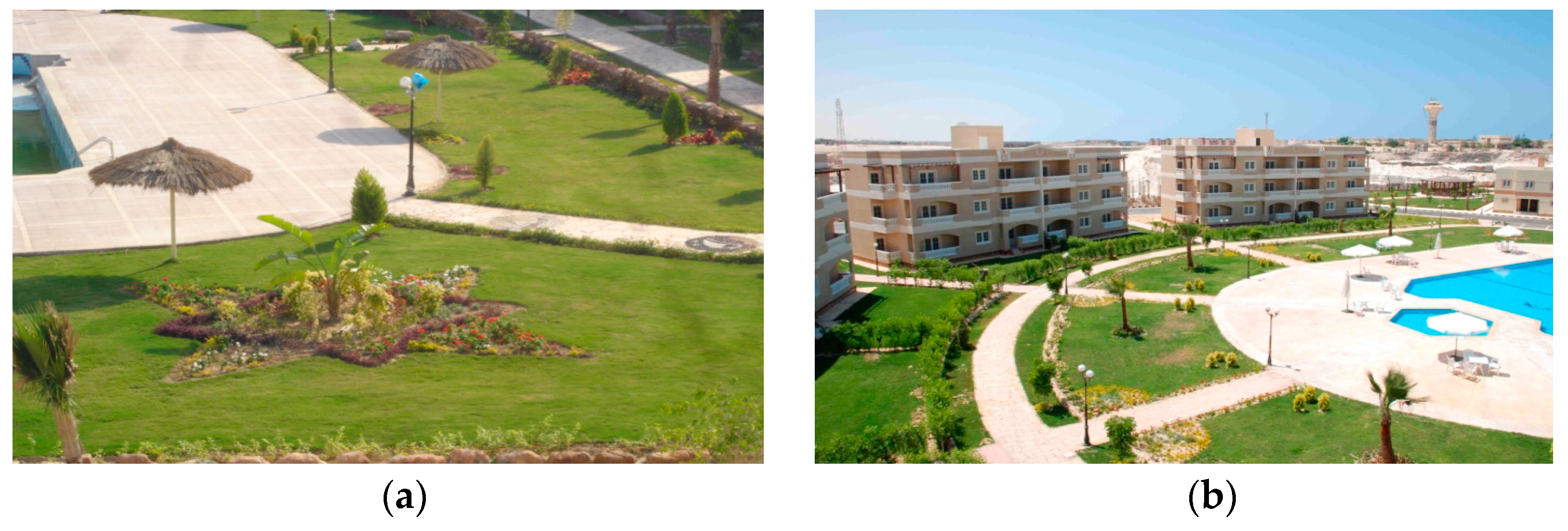

- As for Palm Beach village, despite the appropriate scale and size of the shared space, it appears weak, due to the lack of necessary standards and ingredients that strengthen an individual’s internal sense of being within the natural environment, which is caused by the lack of landscape elements with special natures (13%). In addition, the space does not present any variation in the landscape element (10%), since the urban designer has only covered the space with a green cover (Figure 8) and solid concrete floors that provide stagnation and boredom.

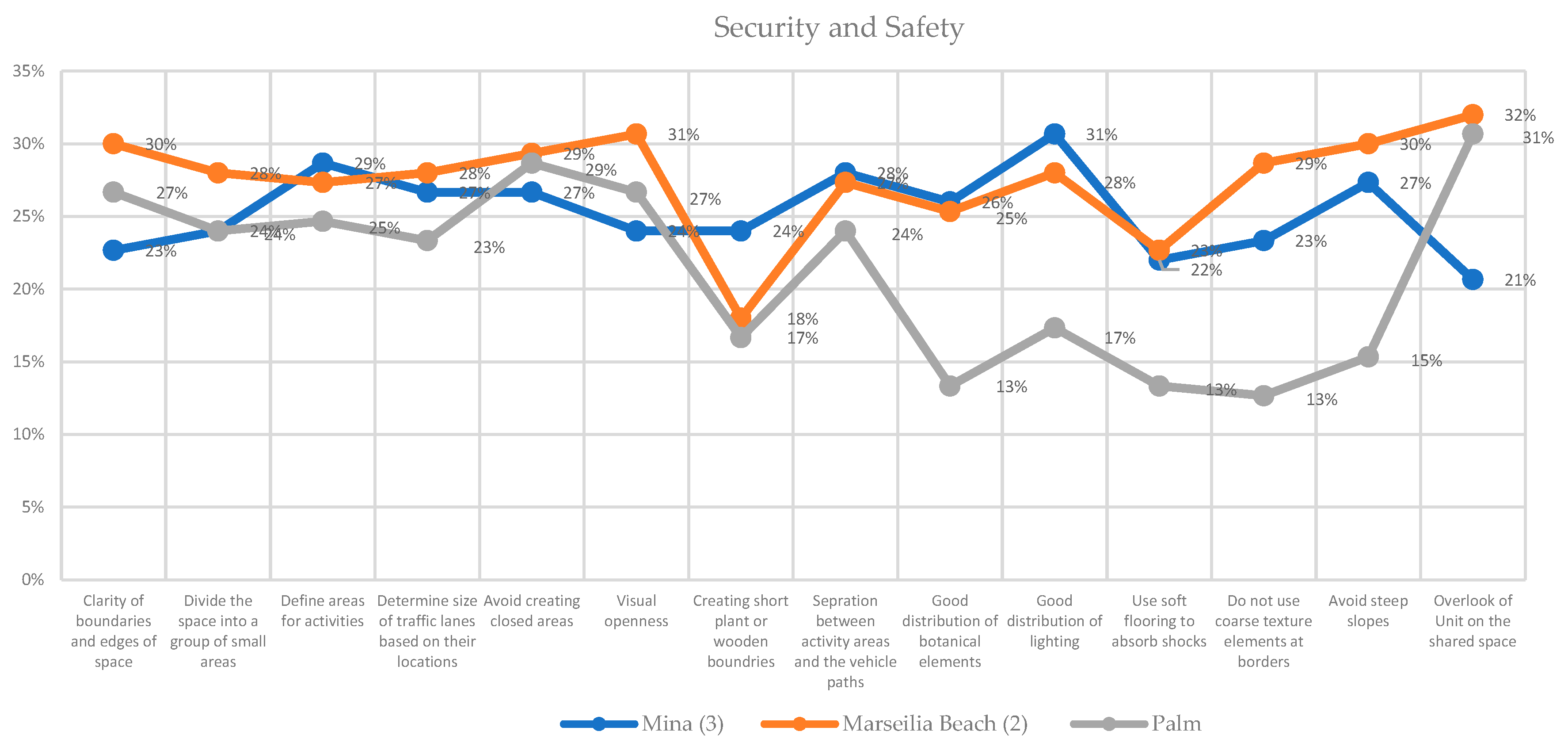

5.1.2. Security and Safety

5.2. Visual Needs

5.3. Social Needs

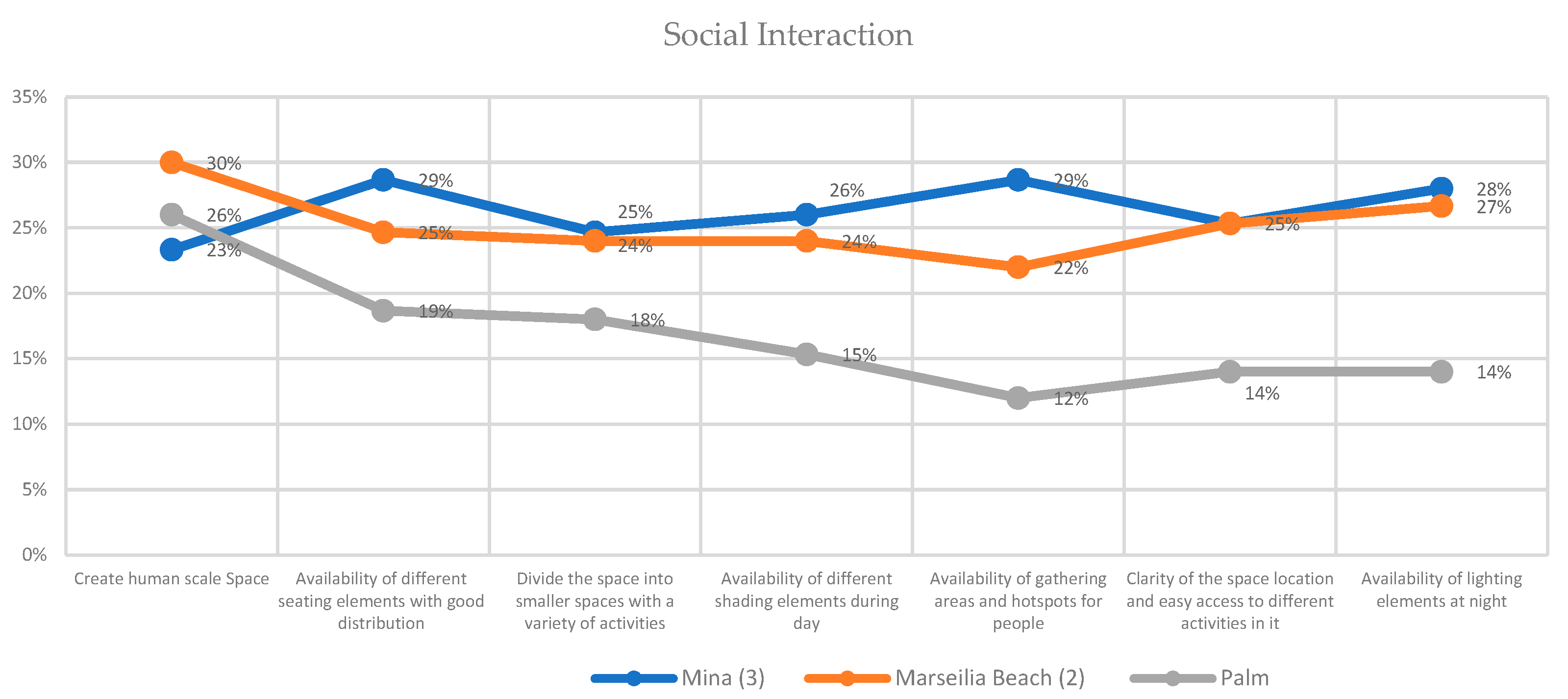

5.3.1. Social Interaction

- Dividing the space into smaller and varied spaces (25%) that serve the different activities of users.

- Providing seating in multiple styles (29%) that allow users to sit collectively or sit alone.

- Availability of shaded areas such as pergolas; however, they were not sufficient in such a huge space.

- Connecting all noisy activities, such as playgrounds, the commercial area, and the swimming pool, in same area and locating them at the beginning of the shared space and far from the residential areas.

- Presence of central areas along the shared space in various forms, which provide good opportunities for social interactions between users.

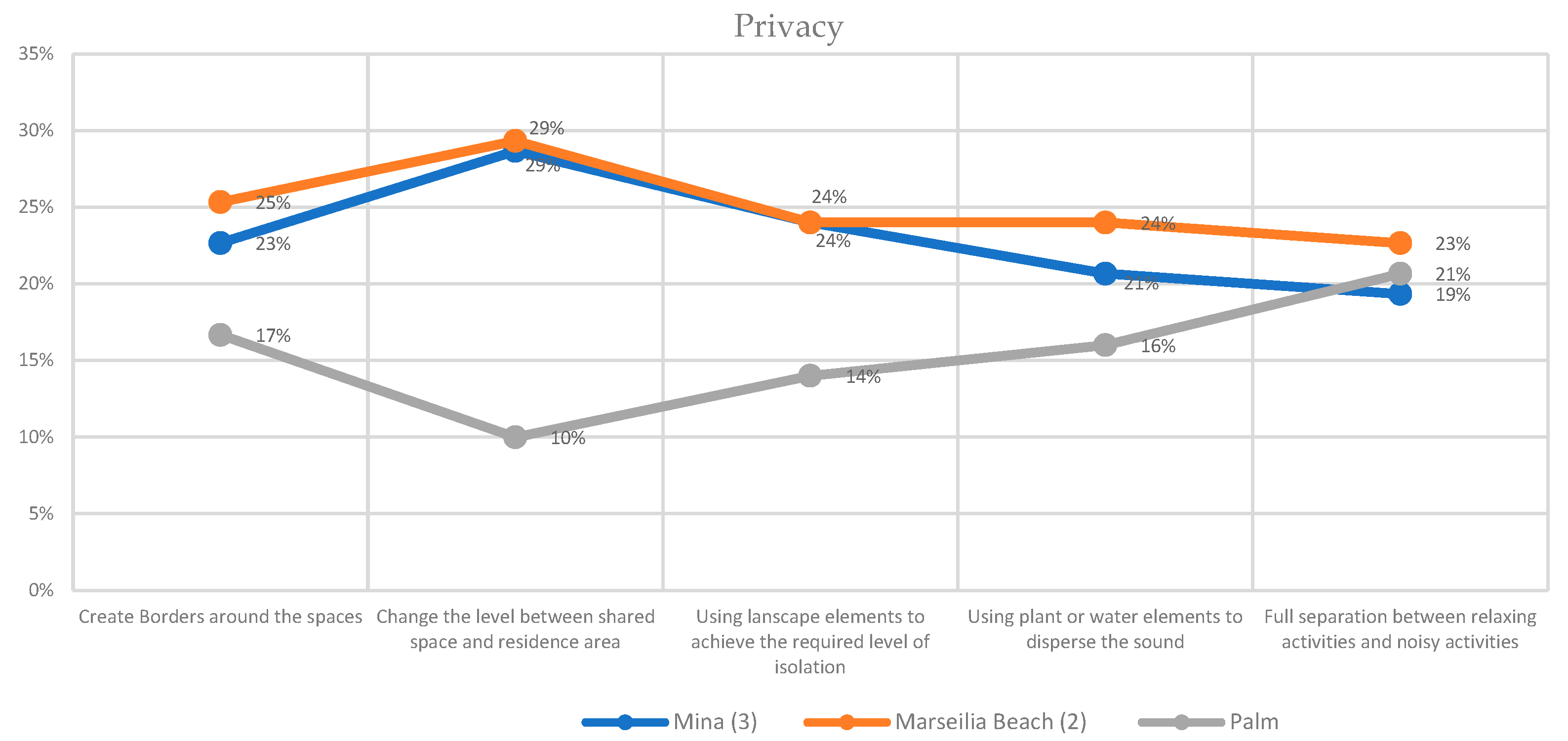

5.3.2. Privacy

5.4. Functional Needs

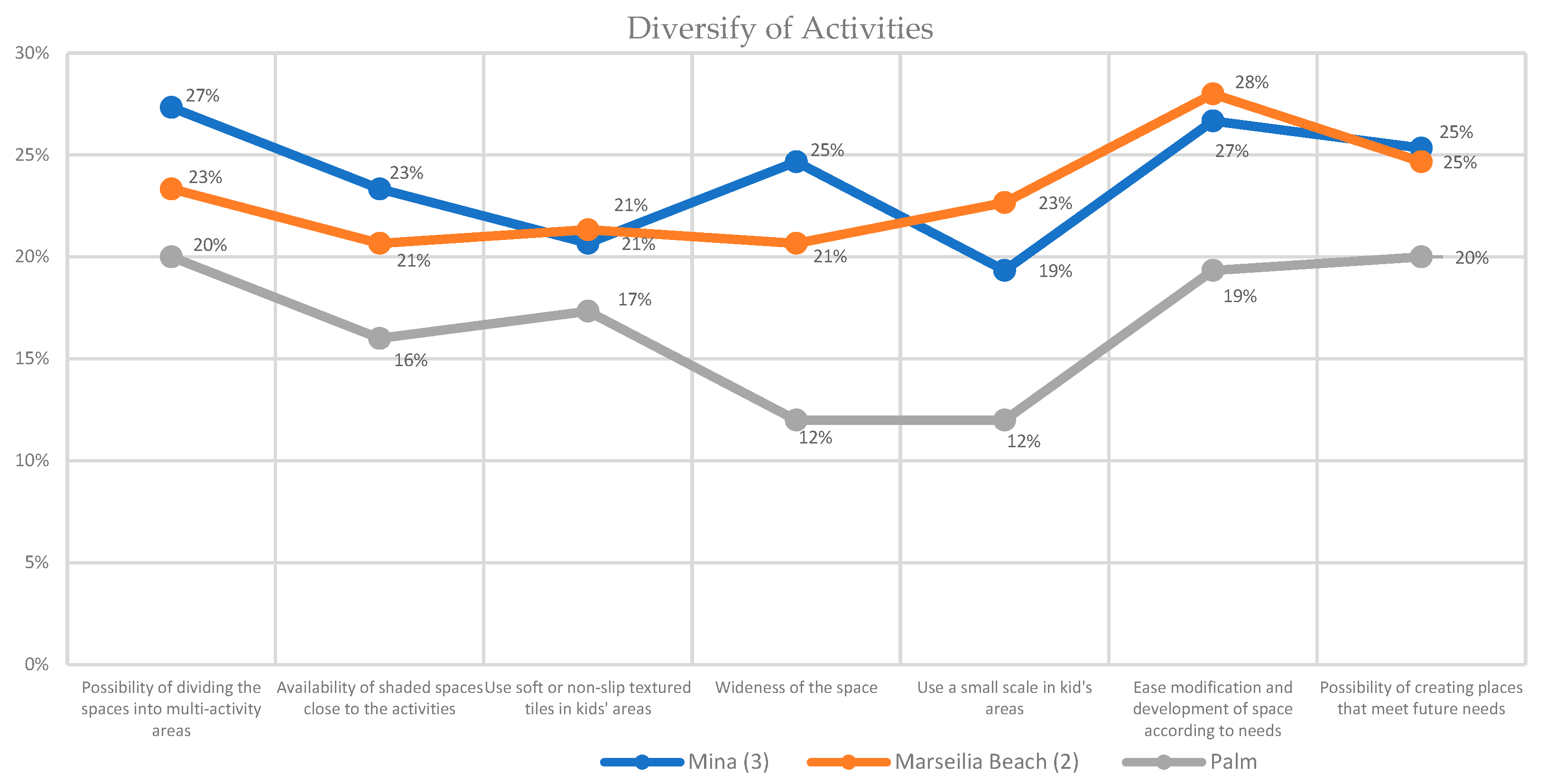

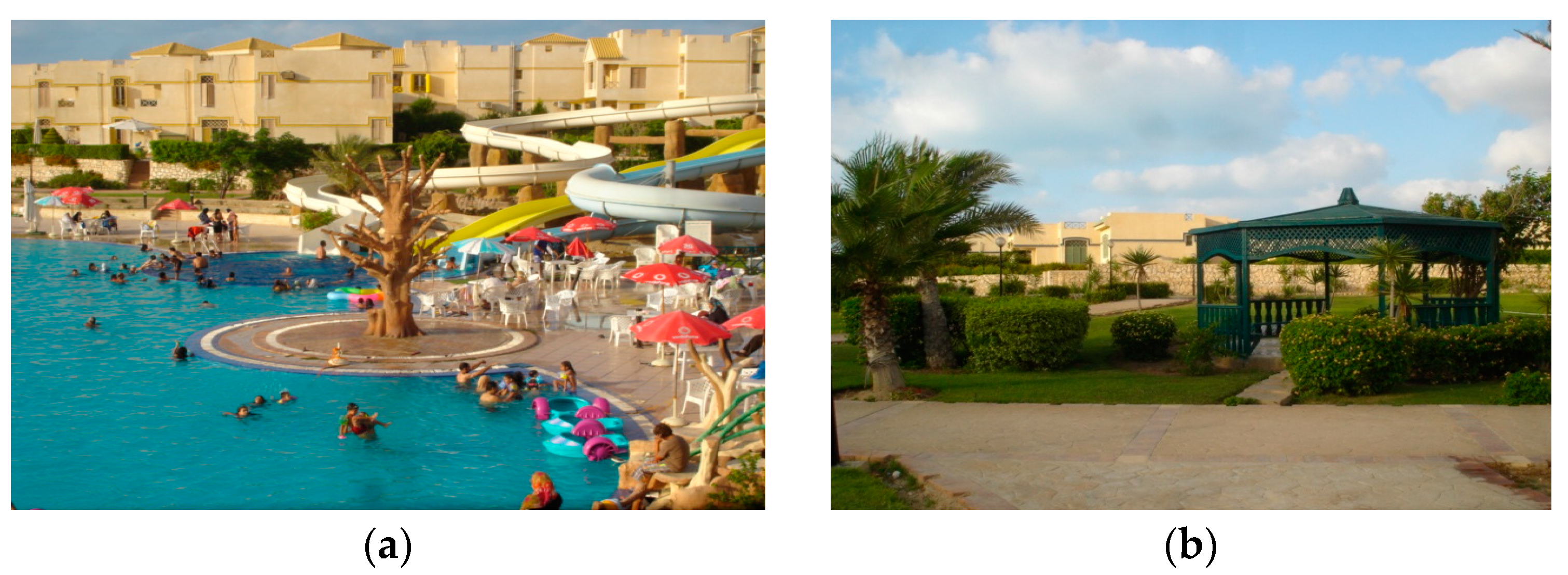

5.4.1. Diversity of Activities

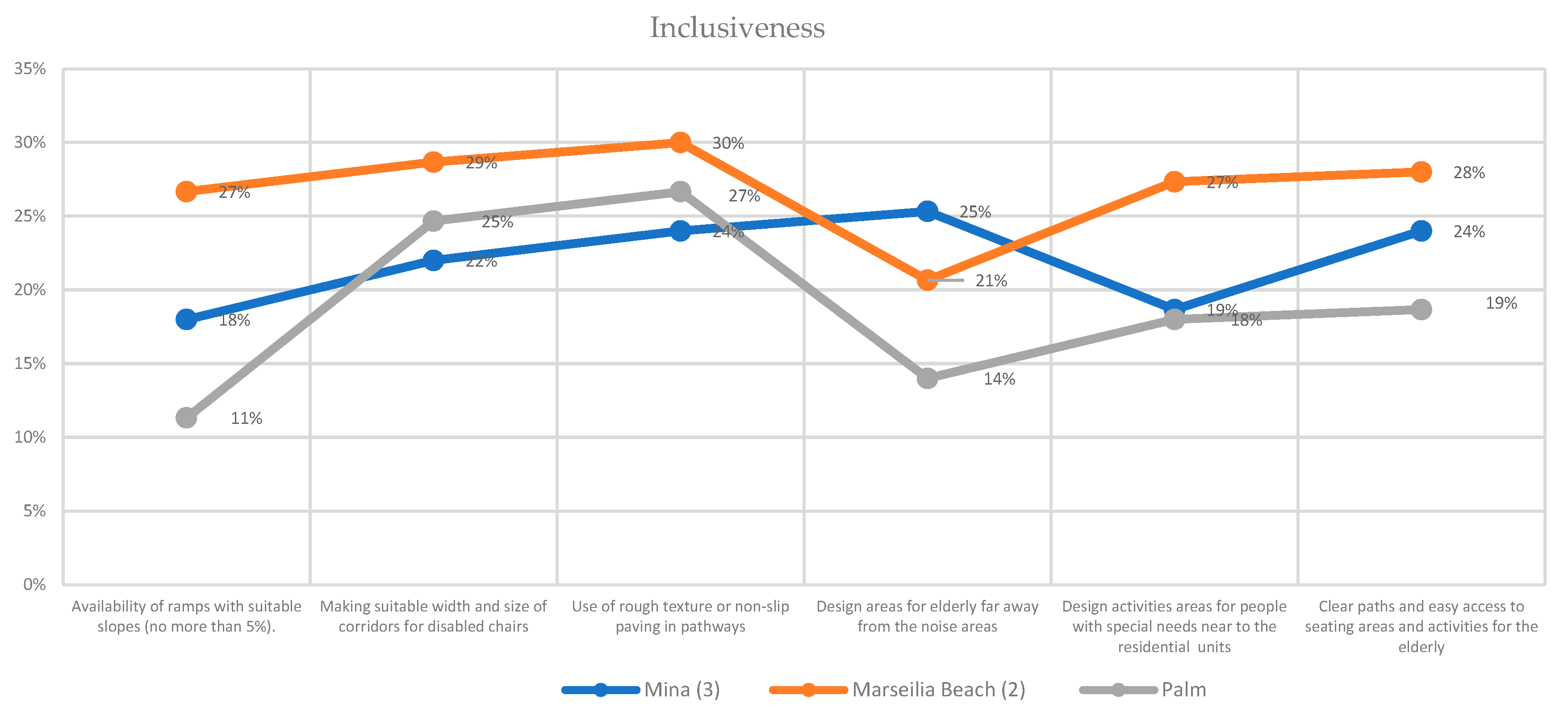

5.4.2. Inclusiveness

5.4.3. Environmental (Climatic) Comfort

6. Conclusions

- The size of the urban open space affects the individual’s sense of belonging and their ability to integrate with nature. A medium size is the best, which has a length-to-width ratio of 1:2. In addition, the height of the surrounding units and the human scale should be taken into consideration. Moreover, the use of various natural elements in shaping and forming shared open spaces can produce psychological comfort for users.

- Users’ feeling of safety and security is affected by several factors; the most important factor is the size and location of the shared open space; its size should not exceed the ratio 1:2, and its location should be exposed and overlooked by the largest number of units. Moreover, the availability of necessary lighting units and consideration of their types and specifications when distributing them will promote the feeling of safety for users. Another essential factor and design criterion that should be taken into account when designing kids’ play areas is full separation between roads with vehicles and these special areas so parents will feel safe to leave their kids inside the urban space.

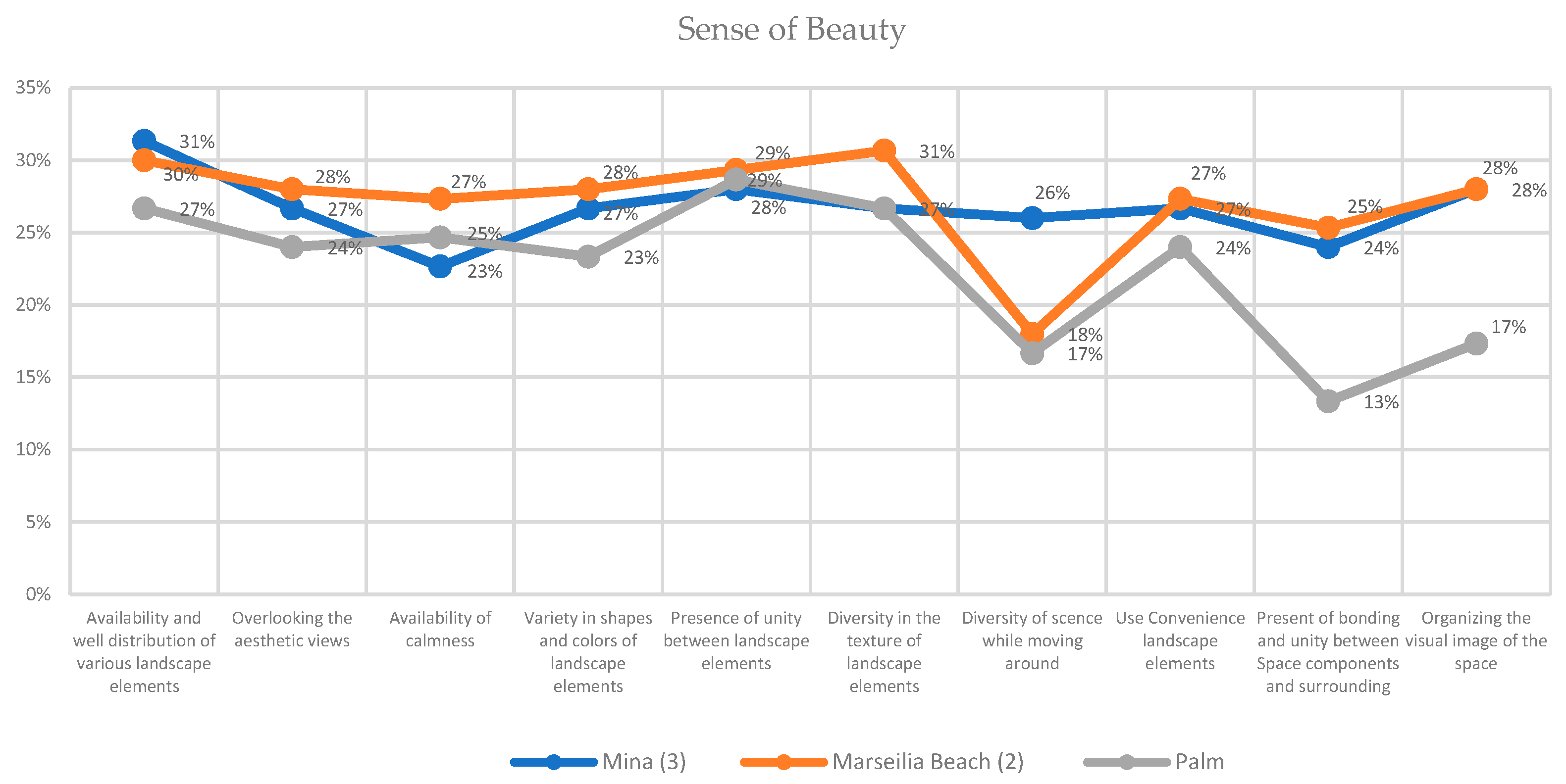

- Users’ sense of beauty is affected by their perception of the space and, therefore, the visual characteristics of urban spaces, such as unity, rhythm, balance, and diversity. Urban designers should be aware of the physical characteristics of the landscape elements and be able to anticipate different design principles to boost the efficiency of these shared spaces.

- Social interaction between users depends on the availability of gathering areas and the diversity of seating types and the way they are distributed in the shared open spaces to suit the different desires of users to interact. Moreover, sufficient shading elements must be available during the day with lighting units at night to encourage users to stay in these shared open spaces.

- Good distribution of the various activities inside these shared open spaces helps in achieving the required level of privacy. This could be accomplished by grouping activities with a noisy nature away from relaxation areas or separating them by using fences and adding sound-dispersing elements such as fountains or dense trees.

- The diversity of activity patterns and the existence of areas for practicing them are crucial functional needs. Consequently, urban designers must be aware of various types of activities during the design process to provide appropriate environment with a diversity of arrangements or possible modifications to meet the future needs of users.

- Urban designers need to be more considerate of the needs of the elderly and people with disabilities by providing horizontal movements such as ramps and considering their slope (not exceeding 5%), and the finishing material must have a rough or anti-slip texture. Moreover, the locations of their activities should be clear and easy to access through the shortest route with the least distance. A possibility is separating the movement pathways of the disabled and the elderly from other pathways so that they can move freely without fear of colliding with pedestrians.

- Studying the economic dimensions of landscape design in the design process of urban open spaces and the impact of value engineering on cost reduction without compromising quality.

- Studying the environmental performance of urban spaces in coastal tourist villages and the impact of the planning patterns and systems on them.

- Studying the environmental effects of construction materials within coastal tourist villages.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheppard, M. Essentials of Urban Design; Csiro Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dioko, L.A.N. The problem of rapid tourism growth: An overview of the strategic question. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hayllar, B.; Griffin, T.; Edwards, D. City Spaces-Tourist Places: Urban Tourism Precincts; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying Core Indicators of Sustainable Tourism: A Path Forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujanah, S.; Ratnawati, T.; Andayani, S. The strategy of tourism village development in the hinterland Mount Bromo, East Java. J. Econ. Bus. Acc. 2015, 18, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, R. Measuring Tourism: Methods, Indicators, and Needs. In The Future of Tourism: Innovation and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, S.; Gallion, A. The Urban Pattern; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Signoretta, P.; Cuesta, R.; Sarris, C. Urban Design: Method and Techniques; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bosone, M.; Nocca, F. Human Circular Tourism as the Tourism of Tomorrow: The Role of Travellers in Achieving a More Sustainable and Circular Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, C.; Van den Bosch, M.; Nielsen, A.; Maruthaveeran, S. Benefits of Urban Parks A systematic review—A Report for IFPRA. Cph. Alnarp 2013, 6, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra, M.; Chattopadhyay, S. Advancing smartness of traditional settlements-case analysis of Indian and Arab old cities. Int. J. Sustain. Built Env. 2016, 5, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, H. Urban Open Spaces; Spon Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand, P.; Rivas, I.; Basagaña, X.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Su, J.; Pascual, M.D.C.; Amato, F.; Jerret, M.; Querol, X.; Sunyer, J. The association between greenness and traffic-related air pollution at schools. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 523, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Yang, S.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Shi, L.; Wu, L.; Hao, F.; Cai, M. Combining multi-source data to explore a mechanism for the effects of micrometeorological elements on nutrient variations in paddy land water. Paddy Water Environ. 2017, 15, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Dictionaries. 2022. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/sustainability?q=sustainability (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Al-Jokhadar, A. Common space as a tool for social sustainability. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 37, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Brown, C.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Watkins, D. Social Acceptability. In Dimensions of the Sustainable City; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Saifuddin, A.; Sedaghatnia, S.; Lamit, H. Urban Social Sustainability Contributing Factors in Kuala Lumpur Streets. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 201, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, M.; Stren, R.E. The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; p. 75. ISBN 080208320X. [Google Scholar]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. The Structural Relationship between Tourist Satisfaction and Sustainable Heritage Tourism Development in Tigrai, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Imagining Biophilic Cities. In Emergent Urbanism: Urban Planning & Design in Times of Structural and Systemic Change; Haas, T., Olsson, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, R.; Sobhani, A.; Meijers, E. The cities we need: Towards an urbanism guided by human needs satisfaction. Urb. Stud. 2022, 59, 2638–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, W.C.; Chang, C.Y. Landscapes and Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiechi, T.; Pryce, J.; Eijdenberg, E.; Azzali, S. Rethinking the Contextual Factors Influencing Urban Mobility: A New Holistic Conceptual Framework. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollard, P. Crime Prevention through Housing Design; E&FN Spon, An Imprint of Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.M.; Robinson, B.; Farrall, S.D. Gender, Fear of Crime and Self-Presentation: An Experimental Investigation. Psychol. Crime Law 2011, 17, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrad, B.; Bahrami, B. The impact of public spaces physical quality in residential complexes on improving user’s social interactions; case study: Pavan residential complex of Sanandaj, Iran. J. Civ. Eng. Urban 2015, 5, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C.; Watkins, D. Social sustainability and urban form: Evidence from five British cities. Environ. Plan. 2009, 41, 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, N. Effects of outdoor shared spaces on social interaction in housing in Algeria. Fronti. Archit. Res. 2013, 2, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.T.; Mori, S.; Nomura, R. An Analysis of Relationship between the Environment and User’s Behavior on Unimproved Streets: A Case Study of Da Nang City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enssle, F.; Kabisch, N. Urban Green Spaces for the Social Interaction, Health and Well-Being of Older People—An Integrated View of Urban Ecosystem Services and Socio-Environmental Justice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovi’c, S.K.; Šestovi´c, J.B. Creative Street Regeneration in the Context of Socio-Spatial Sustainability: A Case Study of a Traditional City Centre in Podgorica, Montenegro. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloggi, F. The value of privacy for social relationships. Soc. Epistem. Rev. Reply Collect. 2017, 6, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Roessler, B.; Mokrosinska, D. Privacy and social interaction. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2013, 39, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Place value: Place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, A.; de Vries, S. Linking Green Space to Health: A Comparative Study of Two Urban Neighbourhoods in Ghent, Belgium. Popul. Environ. 2012, 34, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, R. Role of Local Festivals in Promoting Social Interactions and Shaping Urban Spaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference for Sustainable Design of the Built Environment (SDBE), London, UK, 20–21 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ramayah, T. A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.; Valentine, K.; Knopf, R.; Vogt, C. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerron, G.; Mourato, S. Happiness Is Greater in Natural Environments. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Would You Be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Develop. 2011, 17, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, A. Thermal comfort in transition spaces. Buildings 2013, 3, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.D.; Sun, R.H.; Liu, H.L. Eco-environmental effects of urban landscape pattern changes: Progresses, problems, and perspectives. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xu, S.; Yang, D.; Wang, H. Thermal Environmental Effects of Park Landscape of Main Urban Region in Wuhan. Remote Sens. Inf. 2021, 36, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Fang, Z. Thermal environment effects of urban human settlements and influencing factors based on multi-source data: A case study of Changsha city. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 2443–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, C.; Rehdanz, K. The Role of Urban Green Space for Human Well-Being. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Fracis, C. People Places-Design Guidelines for Urban Open Spaces; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. Creative Cities: The Challenge of “Humanization” in the City Development. BDC Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2013, 13, 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Human-Centered City: Opportunities for Citizens through Research and Innovation; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019.

- European Commission. The Human-Centered City: Recommendations for Research and Innovation Actions; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Vanderstoep, S.W.; Johnston, D.D. Research Methods for Everyday Life: Blending Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Mina (3) | Marseilia Beach (2) | Palm Beach | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Director | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Security Manger | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Security | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| Gardener | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Engineering Management Department | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Mina (3) Village | Marseilia Beach (2) Village | Palm Beach Village | |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  | |

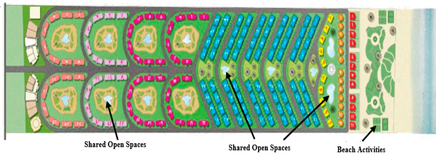

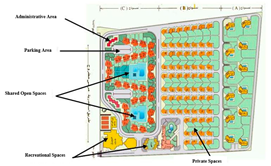

| Description | Mina (3) Village is located at kilometer 76.5 of the Alexandria–Matrouh Road, with an area of 63 acres. The village consists of 410 housing units that vary between villas, chalets, and residential units. The height of the units ranges between two and three floors. These units occupy 15% of the total area of the village. In addition, there are recreational areas such as swimming pools, social clubs and shops topped with a seating area, sport courts, kids’ play areas near the swimming pool, and open theatre areas | Marseilia Beach (2) Village is located at kilometer 72 of the Alexandria–Matrouh Road. Its area is 64.7 acres, where 12.94 acres are built-up areas divided into residential units, commercial area, the mosque, and the rest (51.76 acres) is divided among the shared open spaces between the units and includes swimming pools, parking areas, and a beach that extends for 250 m. The residential units constitute about 17% of the total area. The village consists of 463 housing units that vary between private palaces, villas, chalets, and apartments of different sizes. In addition, it has 26 swimming pools distributed among all the residential areas, a commercial area, kids’ play areas, recreational areas of multiple sizes between the units, and parking areas divided to serve each group separately | Palm Beach is located at kilometer 68 of the Alexandria–Matrouh Road. It includes residential areas of 32,7 acres and 1 acre for the services area, in addition to the beach, which extends for a distance of 500 m. The village consists of 220 housing units that vary between private palaces, duplex villas, chalets, and apartments. The heights of the buildings do not exceed two floors. This results in a low building density, as the proportion of buildings is approximately 12% of the total area of the village. The recreational area is placed on the border of the village near the main gate. It includes a social club, volleyball courts, commercial areas, and a cafeteria |

| The Village Design | The urban designer’s idea aims to create pleasant and comfortable environment for the owners, as he directed most of the units to face the sea (northwest direction). In addition, he created different levels to allow the visual access of a high percentage of the units to the sea as well as creating visual privacy. | The urban designer relied on providing a great opportunity for users to enjoy nature by adding water elements in all areas, mainly swimming pools scattered inside the village and between the units. Although he raised the level of the residential unit area, some units were not able to see the sea, especially the lower units. | The urban designer relied on providing the opportunity for the largest number of units to see the sea; in addition, he made a full separation between the residential and service areas, as most of the services were placed near the main gate, and this led to creation of calm residential areas |

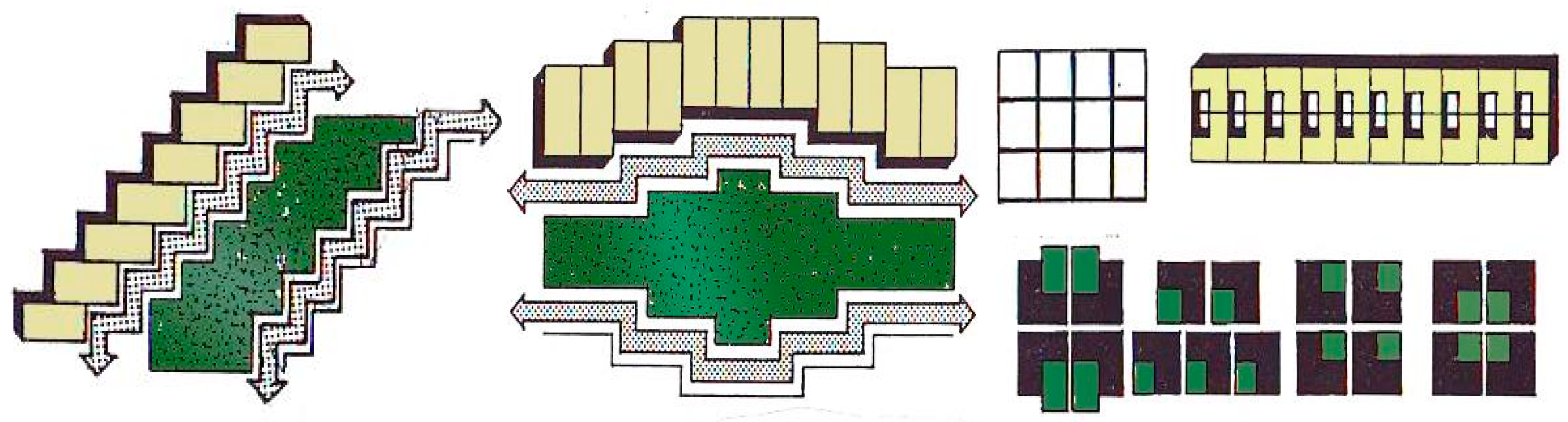

| Urban Fabric | A U-shaped assembly was used, which helped create a small internal space in the middle of a group of units, in addition to the parking space, which is relatively far from these spaces. The urban designer created a central, open, shared space with a width of 75 m, extending over the entire length of the site, about 600 m. This contains most of the recreational activities that the owners need, and they can access the small spaces in the middle of the units and, through the stairs, the upper levels. This helped most of the units to enjoy the view of the sea. | The urban designer creates diversity in the urban fabric formation based on the units’ type, where he kept palaces in the first rows of the beach and away from other units to create privacy, and followed by linear clusters of villas parallel to the beach. Then, the area of chalets that appears as parallel rows to the beach which prevent the last row units from seeing the sea. As for the apartment area, the urban designer succeeded in providing privacy and a good orientation, as he used U-shaped grouping pattern, that allows units to look over as well as reduce the height of the ground level, which helps in providing a good view of the sea, especially for units located on the upper floors. | The urban designer used many urban fabric patterns to increase the chance for many units to see the sea. He used a staggered, pointed style when distributing palaces, then a linear grouping for the private chalets and villas. In addition, he made the small-sized apartments inclined at an angle, placed them in a sequential manner, raised their level to allow them to see the sea, and created a pedestrian pathway in the middle of these units to reach the beach. |

| Urban Space Formation | The shared space is considered a free open dynamic, which has an irregular shape. In addition, it is located as a central space with a monumental scale. | The shared space is a static open space with a primary regular shape. In addition, it is located as a central space between each group of units with a human scale. | The shared space is a static open space with a primary regular shape. In addition, it is located as a central space between each group of units with a human scale. |

| Urban Space Components | Urban Space Floor: The urban designer relied on green covers for the space’s floor formation, and they were interspersed with pathways of hard tiles that can endure high density and corrosion | Urban Space Floor: The urban designer combined green covers and concrete floors, which were designed naturally, giving the users the feeling that they are made of natural materials, such as rocks and stones. | Urban Space Floor: The urban designer relied on green covers and decorative concrete paving in shaping the floor and dividing the group of spaces, while the rest were defined by hard concrete floors that resist corrosion |

| Urban Space Walls: The urban space is open, as it is not surrounded by landscape elements. Meanwhile, its formation as a central space in the middle of the buildings makes it appear closed through the surrounding buildings. | Urban Space Walls: The space is considered semi-closed, as it is surrounded by short walls that were used as barriers. These were in the form of tree trunks and piled stones, providing a natural form. The wall did not prevent people from enjoying seeing the space while they were sitting inside the units. | Urban Space Walls: The space is considered open as there were no elements used as walls, but it was surrounded by the units overlooking it. Thus, the idea of visual openness was realized inside it, since its proportion is considered medium. | |

| Urban Space Ceiling: The urban space is not covered but was left open to the sky, except for the areas of the pergolas, which were shaded, as well as the movable umbrellas that were placed at the swimming pools. | Urban Space Ceiling: The space is not covered but was left open to the sky. There were fixed umbrellas on the edges of all the small spaces, in addition to movable umbrellas that were placed at the swimming pools. | Urban Space Ceiling: The space is not covered but was left open to the sky. There were some movable large umbrellas to create shaded spaces. |

| Mina (3) | Marseilia Beach (2) | Palm Beach | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration With Nature | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Safety and Security | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Sense of Beauty | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Social Interaction | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Privacy | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Diversify the activities | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Inclusiveness | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  | |

| Environmental Comfort | Spatial Formation |  |  |  |

| Landscape Elements |  |  |  | |

| Design Criteria |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moussa, R.A. A Responsive Approach for Designing Shared Urban Spaces in Tourist Villages. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097549

Moussa RA. A Responsive Approach for Designing Shared Urban Spaces in Tourist Villages. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097549

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoussa, Rasha A. 2023. "A Responsive Approach for Designing Shared Urban Spaces in Tourist Villages" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097549

APA StyleMoussa, R. A. (2023). A Responsive Approach for Designing Shared Urban Spaces in Tourist Villages. Sustainability, 15(9), 7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097549