COVID-19 Spatial Policy: A Comparative Review of Urban Policies in the European Union and the Middle East

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

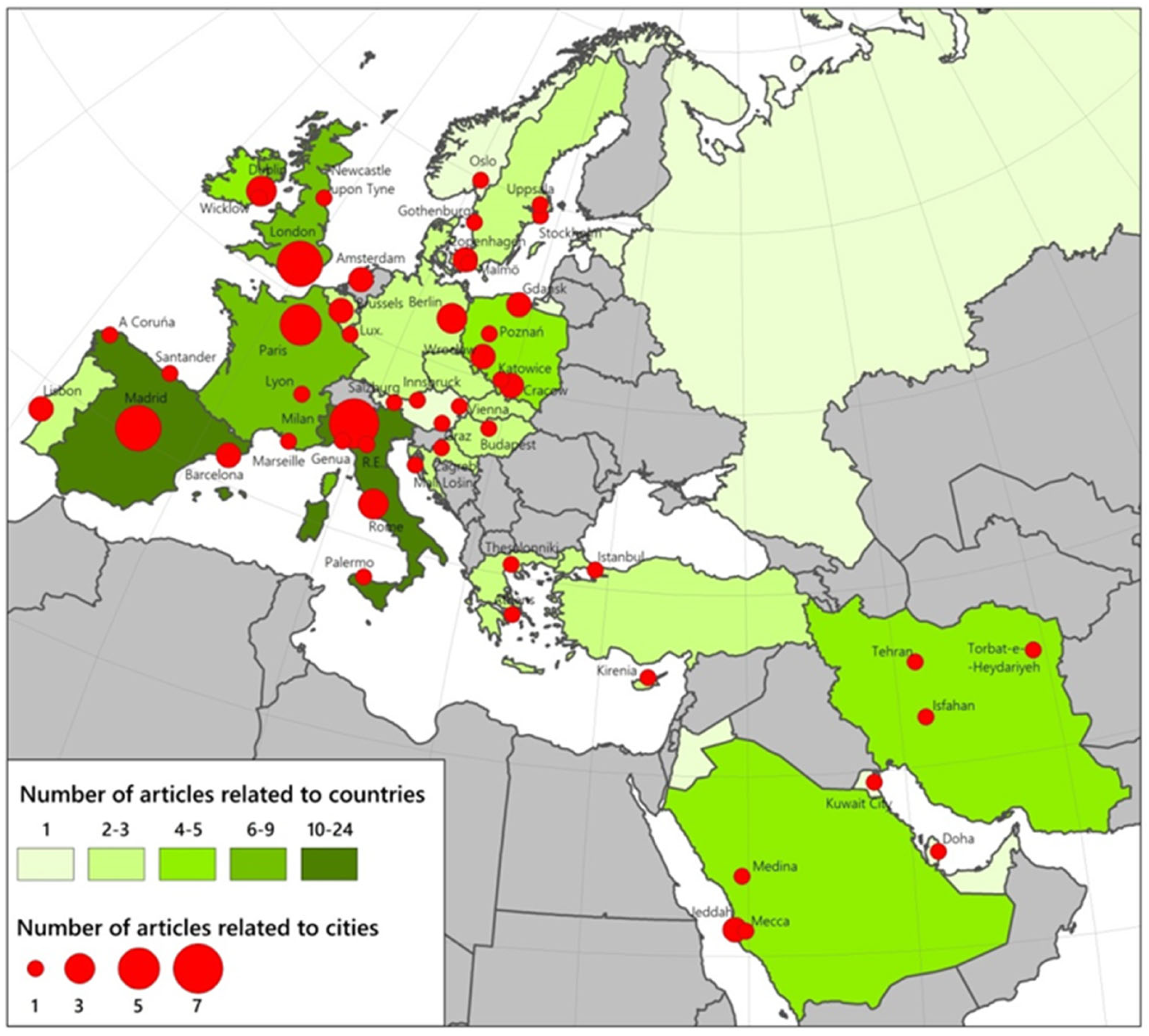

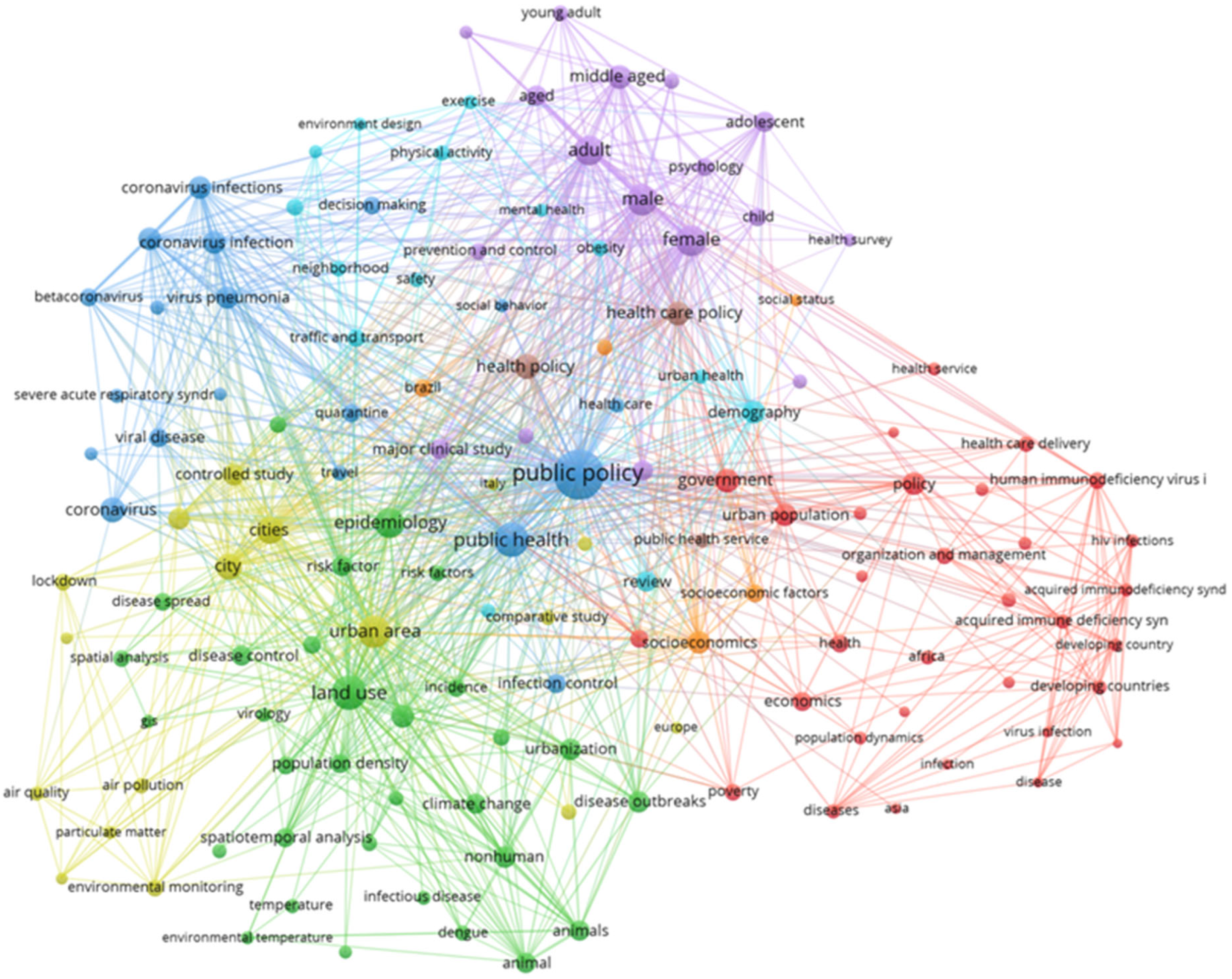

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Thematic Areas

2.3. Principles for Analyzing the Content of Publications

3. Results

3.1. Public Management, the Structure of Public Administration

3.2. Spatial Organization

3.3. Economy

3.4. Transport, Mobility

3.5. Society, Social Cohesion

3.6. Environmental Protection, Sanitation

3.7. Health Protection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| MAIN ISSUES | SPECIFIC TOPICS | Number of Articles in Which the Issue Is Addressed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PUBLIC MANAGEMENT, STRUCTURE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION | A1 | Recentralization (increase in the role of the state) | 9 |

| A2 | Promotion of public governance (and related concepts) | 16 | |

| A3 | Increase in importance of health care in the structure of administration | 8 | |

| A4 | More integrated development planning | 13 | |

| A5 | Increase in importance of digital tools in the administration (e-administration) | 16 | |

| A6 | Changes in administrative-territorial system | 4 | |

| A7 | Other | 0 | |

| Total | 66 | ||

| SPATIAL ORGANIZATION | B1 | Reorganization of the urban structure | 34 |

| B2 | New directions for the development of public spaces (e.g., urban recycling) | 27 | |

| B3 | Restrictions on the use of selected public spaces | 23 | |

| B4 | Reorganization of the location of health care facilities | 12 | |

| B5 | Reorganization of the distribution of educational facilities | 5 | |

| B6 | Reorganization of the distribution of social care facilities | 10 | |

| B7 | Other | 3 | |

| Total | 114 | ||

| TRANSPORT, MOBILITY | C1 | Reorganization of public transport (in general) | 28 |

| C2 | Improvement of spatial accessibility (e.g., “city in 15 minutes”) | 9 | |

| C3 | Ecologization of transport (rolling stock) | 12 | |

| C4 | Promotion of more resilient forms of transport (bicycles, bicycle paths, and other infrastructure serving the dispersal of travel) | 21 | |

| C5 | Promoting so-called responsible transport | 15 | |

| C6 | Other | 1 | |

| Total | 86 | ||

| ECONOMY | D1 | Creating conditions and incentives for remote working | 10 |

| D2 | Ensuring local supply chain (e.g., the concept of food zones) | 8 | |

| D3 | Strengthening links with the hinterland (increase in importance of daily urban systems) | 5 | |

| D4 | Limiting connections with distant regions (anti-globalization, deglobalization) | 5 | |

| D5 | Promotion of local entrepreneurship, promoting local patriotism (use of local products and services) | 8 | |

| D6 | Reorganization of tourism, need for changes in “re-massification”, more sustainable model of tourism and recreation | 6 | |

| D7 | Other | 2 | |

| Total | 44 | ||

| SOCIETY, SOCIAL COHESION | E1 | Increase in importance of social cohesion, sense of community | 29 |

| E2 | Addressing structral inequalities embedded in cities | 14 | |

| E3 | Special activities for the most vulnerable socio-economic groups (elderly people, minorities, underprivileged, marginalized, poor, etc.) | 19 | |

| E4 | Increased importance of social welfare, cash transfers to the most disadvantaged groups | 10 | |

| E5 | Changes in the organization of social insurance systems, e.g., health insurance assistance | 16 | |

| E6 | Special measures for active employment | 7 | |

| E7 | Other | 3 | |

| Total | 98 | ||

| ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, SANITATION | F1 | Environmental improvement initiatives (generally) | 21 |

| F2 | Improvement of aerosanitary conditions (e.g., city ventilation) | 9 | |

| F3 | Reduction in air pollution | 13 | |

| F4 | Promotion of green and blue infrastructure | 13 | |

| F5 | Need for spatial structure splitting (more small green and blue areas) | 15 | |

| F6 | Periodic preventive disinfection of public spaces | 9 | |

| F7 | Other | 6 | |

| Total | 86 | ||

| HEALTH PROTECTION | G1 | Strengthening health issues in development policy (generally) | 32 |

| G2 | Actions promoting good physical and mental condition, resistance to diseases | 16 | |

| G3 | Disease monitoring | 10 | |

| G4 | Spatial reorganization of health services, e.g., changes in the location of medical facilities | 4 | |

| G5 | Increased staffing, logistical and financial assistance to health care facilities | 4 | |

| G6 | Public education on epidemic issues | 12 | |

| G7 | Other | 3 | |

| Total | 81 | ||

| TOOLS FOR CHANGE | H1 | Restrictions on spatial mobility | 19 |

| H2 | Special state aid programs | 15 | |

| H3 | Legal and administrative changes in public management systems | 23 | |

| H4 | Fiscal tools (taxes for specific forms of use, economic activity, tax incentives) | 4 | |

| H5 | Other | 3 | |

| Total | 64 | ||

References

- Kunzmann, K.R. Smart Cities After Covid-19: Ten Narratives. disP 2020, 56, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Nowak, M.; Simon, K. Kierunki polityki przestrzennej miast w Polsce a pandemia SARS-CoV-2. Perspektywa medyczna i przestrzenna. Public Policy Stud. 2022, 9, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Cities Policy Responses (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19); OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cave, B.; Kim, J.; Viliani, F.; Harris, P. Applying an Equity Lens to Urban Policy Measures for COVID-19 in Four Cities. Cities Health 2020, 5, S66–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqutob, R.; Al Nsour, M.; Tarawneh, M.R.; Ajlouni, M.; Khader, Y.; Aqel, I.; Kharabsheh, S.; Obeidat, N. COVID-19 Crisis in Jordan: Response, Scenarios, Strategies, and Recommendations. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boschetto, P. Covid-19 and Simplification of Urban Planning Tools. The Residual Plan. TeMA–J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkowska, M. Consequences of the Pandemic and New Development Opportunities for Polish Cities in the (Post-)COVID-19 Era. R-Economy 2020, 6, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Miravet, D.; Domènech, A. COVID-19 and Urban Public Transport Services: Emerging Challenges and Research Agenda. Cities Health 2020, 5, S177–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotti, L. SME in Europe Towards Local Industrial Policy Able to Sustain Innovation Ecosystems to Redesign and Reinforce Prosperity and Resilience in Post-COVID-19: Some Brief Comments. J. US–China Public Adm. 2020, 17, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, M.; Overman, H. Will Coronavirus Cause a Big City Exodus? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1537–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A. Covid-19 as a Social Crisis and Justice Challenge for Cities. Front. Sociol. 2020, 5, 583638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, M.; Magazzino, C. Pollution, Economic Growth, and COVID-19 Deaths in India: A Machine Learning Evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Toshniwal, D. Impact of Lockdown on Air Quality over Major Cities across the Globe during COVID-19 Pandemic. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Impacts on Cities and Major Lessons for Urban Planning, Design, and Management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, F.A.; Lima, S.D.C. Building Healthy Cities: The Instrumentalization of Intersectoral Public Health Policies from Situational Strategic Planning. Saude Soc. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, L. The Middle East and COVID-19: Time for Collective Action. Global Health 2021, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggetti, M.; Trein, P. Policy Integration, Problem-Solving, and the Coronavirus Disease Crisis: Lessons for Policy Design. Policy Soc. 2022, 41, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Guan, C. The Impacts of the Built Environment on the Incidence Rate of COVID-19: A Case Study of King County, Washington. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, G.; Bahrami, B. COVID and the Home: The Emergence of New Urban Home Life Practised under Pandemic-Imposed Restrictions. Cities Health 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.E.; Hill, B.; Siriwardena, A.N.; Tanser, F.; Spaight, R. Rethinking the Health Implications of Society-Environment Relationships in Built Areas: An Assessment of the Access to Healthy and Hazards Index in the Context of COVID-19. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, K.; Yiannakou, A. COVID-19 and Urban Planning: Built Environment, Health, and Well-Being in Greek Cities before and during the Pandemic. Cities 2022, 121, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibert, O.; Baumgart, S.; Siedentop, S.; Weith, T. Planning in the Face of Extraordinary Uncertainty: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Plan. Pract. Res. 2022, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M.; Florida, R.; Michael, A.R. Cities in a Post-COVID World. Urban Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdaoud, M.; Arcuri, G.; Levratto, N.; Succurro, M.; Costanzo, D. Geography of COVID-19 Outbreak and First Policy Answers in European Regions and Cities. Policy Brief 2020. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/GEOCOV%20final%20report.pdf.

- Costa, D.G.; Peixoto, J.P.J. COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Smart Cities Initiatives to Face New Outbreaks. IET Smart Cities 2020, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiello, G. Toward Greener and Pandemic-Proof Cities: Italian Cities Policy Responses to Covid-19 Pandemic. TeMA–J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, 13, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- James, P.; Das, R.; Jalosinska, A.; Smith, L. Smart Cities and a Data-Driven Response to COVID-19. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renigier-Biłozor, M.; Źróbek, S.; Walacik, M.; Janowski, A. Hybridization of Valuation Procedures as a Medicine Supporting the Real Estate Market and Sustainable Land Use Development during the Covid-19 Pandemic and Afterwards. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Leone, F.; Zoppi, C. Covid-19 and Spatial Planning. TeMA–J. Land Use Mobil. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. How Can We Quarantine Without a Home? Responses of Activism and Urban Social Movements in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis in Lisbon. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, C. Strategies for Post-COVID Cities: An Insight to Paris En Commun and Milano 2020. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Alpar Atun, R. Reading the Changing Dynamic of Urban Social Distances during the COVID-19 Pandemic via Twitter. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, S872–S886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favas, C.; Checchi, F.; Waldman, R.J. Guidance for the Prevention of COVID-19 Infections among High-Risk Individuals in Urban Settings 2020; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P.; Nowak, M.; Blaszke, M. Spatial Policy in Cities during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Poland. TeMA–J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, 13, 427–444. [Google Scholar]

- Grofelnik, H. Assessment of Acceptable Tourism Beach Carrying Capacity in Both Normal and COVID-19 Pandemic Conditions-Case Study of the Town of Mali Lošinj. Croat. Geogr. Bull. 2020, 82, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baganz, G.; Baganz, D.; Kloas, W.; Lohrberg, F. Urban Planning and Corona Spaces–Scales, Walls and COVID-19 Coincidences. Shaping Urban Change—Livable City Regions for the 21st Century. Proceedings of REAL CORP 2020. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Urban Development, Regional Planning and Information, Aachen, Germany, 15–18 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kajdanek, K. “Have We Done Well?” Decision to Return from Suburbia to Polish Cities in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. City Soc. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, S. Coronavirus and Urbanization: Does Pandemics Are Anti-Urban? SSRN Electron. J. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colfer, B. Herd-Immunity across Intangible Borders: Public Policy Responses to COVID-19 in Ireland and the UK. Eur. Policy Anal. 2020, 6, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calori, A.; Federici, F. Coronavirus and beyond: Empowering Social Self-Organization in Urban Food Systems. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, P.; Martinico, F.; Nigrelli, F.C. “Passata è La Tempesta…”. A Land Use Planning Vision for the Italian Mezzogiorno in the Post Pandemic. TeMA–J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślikowski, K. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Development of Event Market on the Example of the City of Katowice. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Innovative (Eco-)Technology, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Kaunas, Lithuania, 29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kadi, J.; Schneider, A.; Seidl, R. Short-Term Rentals, Housing Markets and Covid-19: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Evidence from Four Austrian Cities. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2020, 7, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Cots, P.; Palomares-Pastor, M. En Un Entorno de 15 Minutos. Hacia La Ciudad de Proximidad, y Su Relación Con El Covid-19 y La Crisis Climática: El Caso de Málaga. Ciudad Territ. Estud. Territ. 2020, 52, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierstein, A.; Weinig, M.; Cruel, A.; Funke, C.; Höpfner, L.; Miyazaki, T.; Seibert, A.; Sponheimer, D.; Wagner, L. Being Close, yet Being Distanced? Available online: https://journey.live/being-close-while-social-distancing (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Ahmadpoor, N.; Shahab, S. Realising the Value of Greenspace: A Planners Perspective of the Covid –19 Pandemic. TownPlan. Rev. 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudendal-Pedersen, M.; Kesselring, S. What Is the Urban without Physical Mobilities? COVID-19-Induced Immobility in the Mobile Risk Society. Mobilities 2021, 16, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryjakiewicz, T.; Ciesiółka, P.; Jaroszewska, E. Urban Shrinkage and the Post-Socialist Transformation: The Case of Poland. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, A.; Alonso, B.; Benavente, J.; Cordera, R.; Echániz, E.; González, F.; Ladisa, C.; Lezama-Romanelli, R.; López-Parra, Á.; Mazzei, V.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Urban Mobility: Empirical Evidence from the City of Santander (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenelius, E.; Cebecauer, M. Impacts of COVID-19 on Public Transport Ridership in Sweden: Analysis of Ticket Validations, Sales and Passenger Counts. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boston Consulting Group. How COVID-19 Will Shape Urban Mobility. City 2020, 25, 28. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Best Practice in City Public Transport Authorities’ Responses to COVID-19: A Note for Municipalities in Bulgaria 1. City Responses—Decrees Regarding Travel and Behaviour, and Travel Patterns in Response to the Pandemic; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vatavali, F.; Gareiou, Z.; Kehagia, F.; Zervas, E. Impact of COVID-19 on Urban Everyday Life in Greece. Perceptions, Experiences and Practices of the Active Population. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobileye. Mobileye Is Bringing Driverless MaaS to the UAE. Available online: https://www.mobileye.com/blog/mobileye-is-bringing-driverless-maas-to-the-uae/ (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Moradpour, N. Are High-Density Districts More Vulnerable to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-Minute City: Urban Planning and Design Efforts toward Creating Sustainable Neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orro, A.; Novales, M.; Monteagudo, Á.; Pérez-López, J.B.; Bugarín, M.R. Impact on City Bus Transit Services of the COVID-19 Lockdown and Return to the New Normal: The Case of A Coruña (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, I.; Vörösmarty, M.; Gyöngyösi, A.Z.; Thén, W.; Weidinger, T. What Can We Learn about Urban Air Quality with Regard to the First Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Case Study from Central Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 15725–15742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinello, S.; Lolli, F.; Gamberini, R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Emergency on Local Vehicular Traffic and Its Consequences for the Environment: The Case of the City of Reggio Emilia (Italy). Sustainability 2021, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowski, K. Autonomous Transport as an Alternative for Public Transport in the City During an Epidemic Threat. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 23, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraci, F.; Errigo, M.F.; Fazia, C.; Campisi, T.; Castelli, F. Cities under Pressure: Strategies and Tools to Face Climate Change and Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkswagen. ‘Project Qatar Mobility’: Self-Driving Shuttles Set to Take Doha’s Local Public Transport to the Next Level in 2022. Available online: https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/en/press-releases/project-qatar-mobility-self-driving-shuttles-set-to-take-dohas-local-public-transport-to-the-next-level-in-2022-5679 (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Barbarossa, L. The Post Pandemic City: Challenges and Opportunities for a Non-Motorized Urban Environment. An Overview of Italian Cases. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finbom, M.; Kębłowski, W.; Sgibnev, W.; Sträuli, L.; Timko, P.; Tuvikene, T.; Weicker, T. COVID-19 and Public Transport: Insights from Belgium (Brussels), Estonia (Tallinn), Germany (Berlin, Dresden, Munich), and Sweden (Stockholm); DEU: Konak, Turkey, 2021; Volume 40, ISBN 386082113X. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi, J.; Chavoshi, A. Tehran Bike-Sharing System: Providing an Appropriate Approach to Establish Smart Bike-Sharing Stations. Q. J. Transp. Eng. 2017, 9, 258–276. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, L.; Ison, S. Responsible Transport: A Post-COVID Agenda for Transport Policy and Practice. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 6, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, H.V.S.; Anguelovski, I.; Baró, F.; García-Lamarca, M.; Kotsila, P.; Pérez del Pulgar, C.; Shokry, G.; Triguero-Mas, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Power and Privilege, Gentrification, and Urban Environmental Justice in the Global North. Cities Health 2020, 5, S71–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourahmad, A.; Khavarian-garmsir, A.R.; Hataminejad, H. Social Inequality, City Shrinkage and City Growth in Khuzestan Province, Iran. Area Dev. Policy 2016, 1, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, S.; Pandolfini, V.; Torrigiani, C. Frailty and Its Social Predictors Among Older People: Some Empirical Evidences and a Lesson From Covid-19 for Revising Public Health and Social Policies. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 2020, 12, 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Falanga, R. Citizen Participation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from Local Practices in European Cities 2020; Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, M.; Ivankovic, D.; Biermann, O. Early Lessons from COVID-19 Response and Shifts in Authority: Public Trust, Policy Legitimacy and Political Inclusion. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 854–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Juste-Carrión, J.J.; Vásquez-Barquero, A. Local Development Policies: Challenges for Post-COVID-19 Recovering in Spain. Symph. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2020, 2, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S. A Study on the Relationship between Urban Environmental Elements and Depression: Focused on Urban Planning Strategy in the COVID-19 Era. J. Real Estate Anal. 2020, 6, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Mele, M.; Schneider, N. The Relationship between Air Pollution and COVID-19-Related Deaths: An Application to Three French Cities. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legeby, A.; Koch, D., II. Cambiamento Delle Abitudini Urbane in Svezia Durante La Pandemia Di Coronavirus/The Changing of Urban Habits during the Corona Pandemic in Sweden. FAMagazine 2020, 52, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Baldasano, J.M. COVID-19 Lockdown Effects on Air Quality by NO2 in the Cities of Barcelona and Madrid (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, S. Nonlinear Impact of COVID-19 on Pollutions—Evidence from Wuhan, New York, Milan, Madrid, Bandra, London, Tokyo and Mexico City. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschroth, F.; Kowarik, I. COVID-19 Crisis Demonstrates the Urgent Need for Urban Greenspaces. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, C. Nourishing and Protecting Our Urban ‘Green’ Space in a Post-Pandemic World. Environ. Law Rev. 2020, 22, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Özbek, N. Resilience-Oriented Practices in Sea-LevelRise-Induced Human Migration in Coastal Bangladesh and Louisiana. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Impacts Responses 2022, 14, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, N. Bikeability and the Twenty-Minute Neighborhood; Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.F.; Adlakha, D.; Oyeyemi, A.; Salvo, D. An International Physical Activity and Public Health Research Agenda to Inform Coronavirus Disease-2019 Policies and Practices. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.O.; Lee, S.; Park, I.K.; Park, J.; Seo, I. COVID-19 Impact on City and Region: What’s next after Lockdown? Int. J. Urban Sci. 2020, 24, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammary, A.A. Role of Community-Based Measures in Adherence to Self-Protective Behaviors during First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Health Promot. Perspect. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Jiménez-Narros, C.; Perlado-Lamo-de-Espinosa, M.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M. Social Networks’ Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Health Media vs. Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S. Spain to Top Up Incomes of Poorest as Coronavirus Hits Livelihoods. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-spain-poverty-idUSKBN23537F (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Guida, C.; Carpentieri, G. Quality of Life in the Urban Environment and Primary Health Services for the Elderly during the Covid-19 Pandemic: An Application to the City of Milan (Italy). Cities 2021, 110, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassouli, M.; Ashrafizadeh, H.; Shirinabadi Farahani, A.; Akbari, M.E. COVID-19 Management in Iran as One of the Most Affected Countries in the World: Advantages and Weaknesses. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, F.J.; Canora, J.; Zapatero, A.; Barba, R.; González Del Castillo, J.; García-Casasola, G.; San-Román, J.; Gil-Prieto, R.; Barreiro, P.; Fragiel, M.; et al. Temporary Hospitals in Times of the COVID Pandemic. An Example and a Practical View. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2021, 34, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwais, F.A. Physical Activity at Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Two Most-Affected Cities in Saudi Arabia. Open Public Health J. 2020, 13, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban Nature in a Time of Crisis: Recreational Use of Green Space Increases during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, A.; Hewa, T.; Mishra, R.A.; Ylianttila, M.; Liyanage, M. The Role of Blockchain to Fight against COVID-19. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Kummitha, R.K. Contributions of Smart City Solutions and Technologies to Resilience against the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanoska-Dacikj, A.; Stachewicz, U. Smart Textiles and Wearable Technologies-Opportunities Offered in the Fight against Pandemics in Relation to Current COVID-19 State. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2020, 59, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, T.S.H.; Askari, M.; Miri, K.; Nia, M.N. Depression, Stress and Anxiety of Nurses in COVID-19 Pandemic in Nohe-Dey Hospital in Torbat-e-Heydariyeh City, Iran. J. Mil. Med. 2020, 22, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadah, T. Knowledge and Attitude among Healthcare Workers towards COVID-19: A Cross Sectional Study from Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirol, E.; Getaz, L.; Stoll, B.; Chappuis, F.; Loutan, L. Urbanisation and Infectious Diseases in a Globalised World. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, I. Polityka Miejska w Warunkach Kryzysu; University of Gdańsk: Gdańsk, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, S.; Bagheri, B.; Potts, R. Barriers to Employing E-Participation in the Iranian Planning System. Cities 2021, 116, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhoodi, R.; Gharakhlou-N, M.; Ghadami, M.; Khah, M.P. A Critique of the Prevailing Comprehensive Urban Planning Paradigm in Iran: The Need for Strategic Planning. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M. Strategic Decisions on Urban Built Environment to Pandemics in Turkey: Lessons from COVID-19. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheshtawy, Y. Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope; Routledge: Abington-on-Thames, UK, 2004; ISBN 1134410107. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual; Univeristeit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, N. Intelligent Cities: Variable Geometries of Spatial Intelligence. Intell. Build. Int. 2011, 3, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addink, H. Good Governance: Concept and Context; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; ISBN 0198841159. [Google Scholar]

- Markowski, T. Polityka Urbanistyczna Państwa—Koncepcja, Zakres i Struktura Instytucjonalna w Systemie Zintegrowanego Zarządzania Rozwojem; University of Łódź: Łódź, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sniečkutė, M.; Fiore, E. Questioning COVID-19 Pre-Packaged Solidarity Initiatives in the Dutch Urban Spaces. J. Extrem. Anthropol. 2020, 4, E31–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. Exploring the Types of Blogs Cited in Urban Plannig Research. Plan. Pract. Res. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, J.; Drechsler, W.; Hajnal, G. Public Policy during COVID-19: Challenges for Public Administration and Policy Research in Central and Eastern Europe. NISPAcee J. Public Adm. Policy 2020, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; ‘t Hart, P. From Crisis to Reform? Exploring Three Post-COVID Pathways. Policy Soc. 2022, 41, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, H.; Hamza, A.; Nasser, M.S.; Hussein, I.A.; Ahmed, R.; Karami, H. Hole Cleaning and Drilling Fluid Sweeps in Horizontal and Deviated Wells: Comprehensive Review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 186, 106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakderi, C.; Oikonomaki, E.; Papadaki, I. Smart and Resilient Urban Futures for Sustainability in the Post COVID-19 Era: A Review of Policy Responses on Urban Mobility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.L. Pandemic Challenges to Planning Preccriptions: How Covid-19 is Changing the Ways We Think About Planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Rosenberg, M.; Pantyley, V.; Nowak, M.J. Assessing Urban Policies in a COVID-19 World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. Is the pandemic a hope for planning? Two doubts. Plan. Theory 2022, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Combination of the Field “Title” | Cities | City | Land Use | Local Development | Local Policy | Public Participation | Public Policy | Spatial Planning | Spatial Policy | Towns | Urban |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coronavirus | 90 | 227 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 61 |

| covid | 407 | 770 | 2 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 170 | 2 | 3 | 18 | 655 |

| epidemic | 19 | 60 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 45 |

| pandemic | 131 | 353 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 61 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 225 |

| public health | 33 | 138 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 33 | – | 2 | 0 | 3 | 99 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 11 | 116 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| Total | 691 | 1664 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 40 | 278 | 12 | 4 | 30 | 1117 |

| Combination of the Field “Title” | Coronavirus | Covid | Epidemic | Pandemic | Public Healt | SARS-CoV-2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cities | 18 | 7 | 2 | 27 | |||

| city | 1 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 21 | |

| land use | 2 | 2 | |||||

| local development | 1 | 1 | |||||

| local policy | 1 | 1 | |||||

| public participation | 1 | 1 | |||||

| public policy | 5 | 2 | 7 | ||||

| spatial planning | 1 | 1 | |||||

| spatial policy | 11 | 11 | |||||

| urban | 3 | 32 | 4 | 39 | |||

| Total | 4 | 74 | 1 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 111 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Śleszyński, P.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Nowak, M.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Abadi, M.H.H.; Nasiri, N.A. COVID-19 Spatial Policy: A Comparative Review of Urban Policies in the European Union and the Middle East. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032286

Śleszyński P, Khavarian-Garmsir AR, Nowak M, Legutko-Kobus P, Abadi MHH, Nasiri NA. COVID-19 Spatial Policy: A Comparative Review of Urban Policies in the European Union and the Middle East. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032286

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚleszyński, Przemysław, Amir Reza Khavarian-Garmsir, Maciej Nowak, Paulina Legutko-Kobus, Mohammad Hajian Hossein Abadi, and Noura Al Nasiri. 2023. "COVID-19 Spatial Policy: A Comparative Review of Urban Policies in the European Union and the Middle East" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032286

APA StyleŚleszyński, P., Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R., Nowak, M., Legutko-Kobus, P., Abadi, M. H. H., & Nasiri, N. A. (2023). COVID-19 Spatial Policy: A Comparative Review of Urban Policies in the European Union and the Middle East. Sustainability, 15(3), 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032286