International Research Review and Teaching Improvement Measures of College Students’ Learning Psychology under the Background of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Methods and Data Processing

2.1. Research Methods

2.2. Data Processing

3. Bibliometric Results

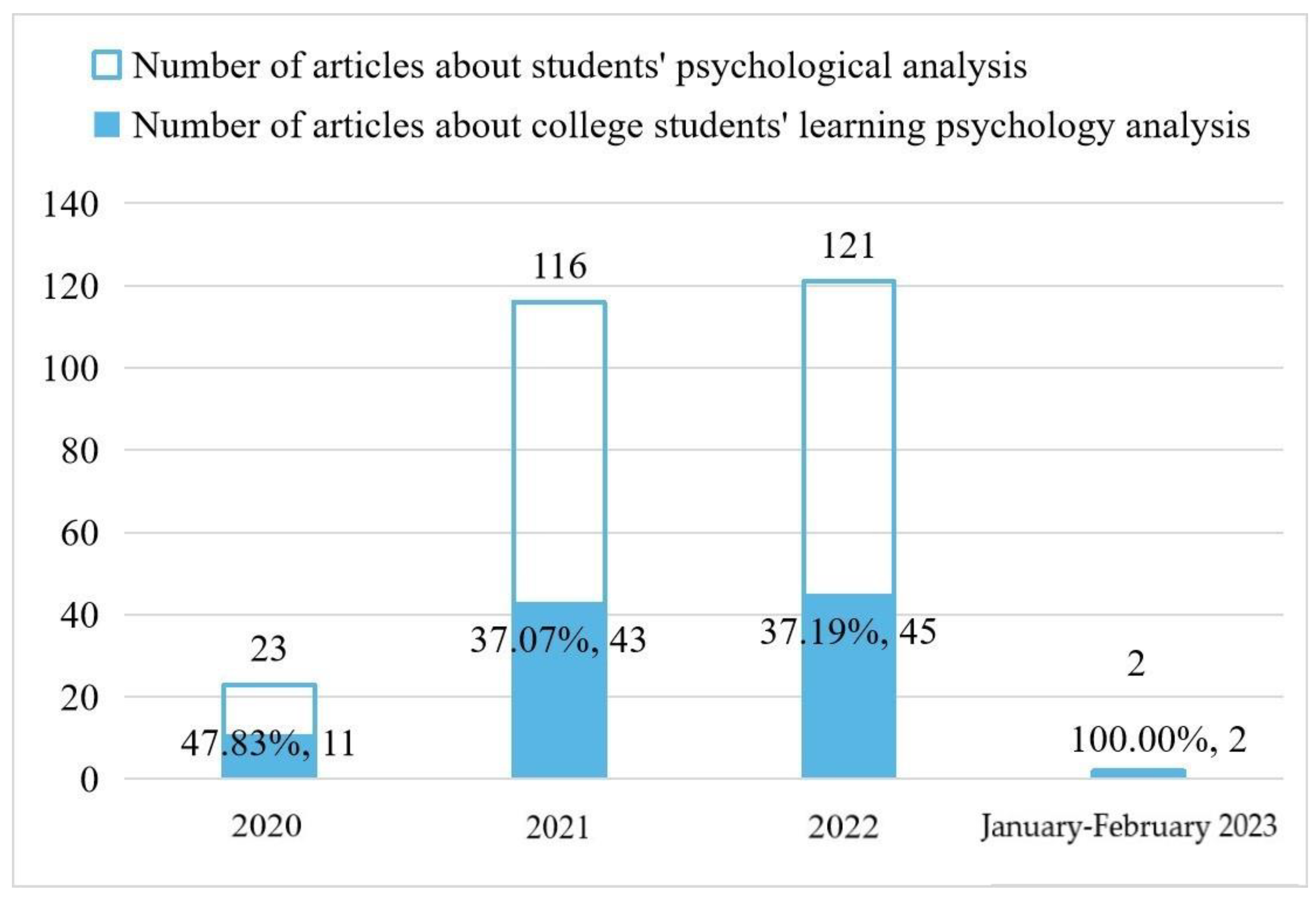

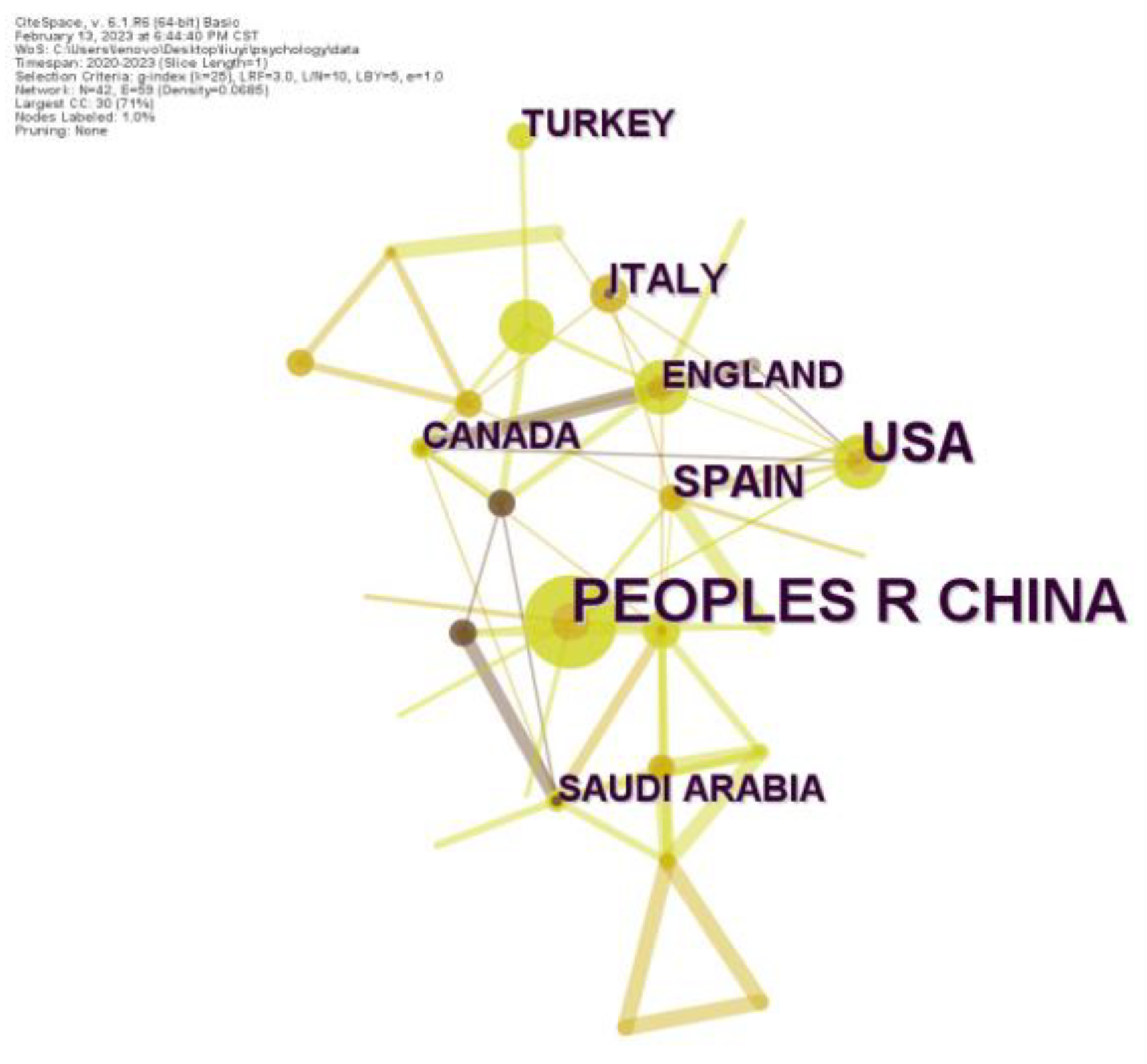

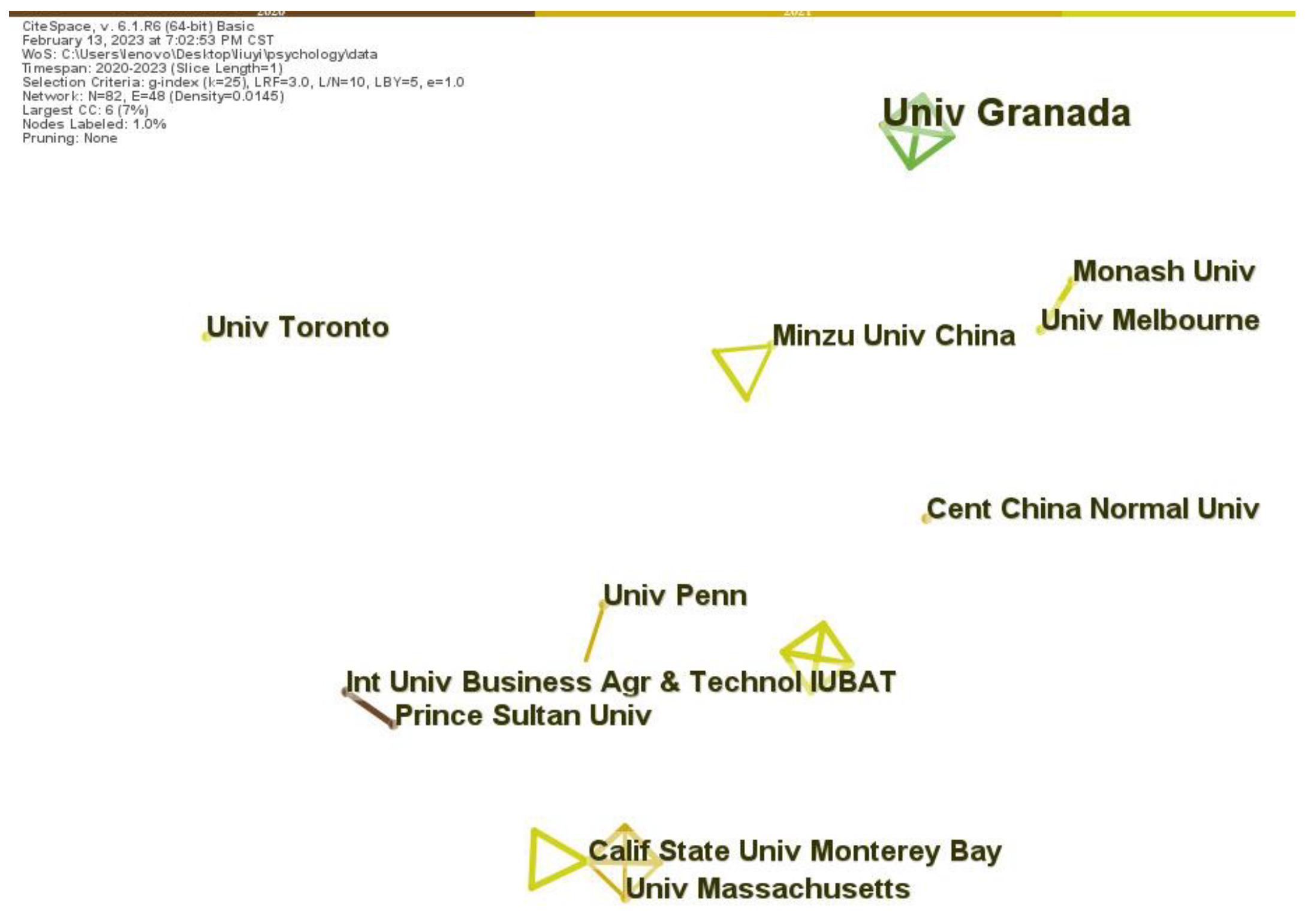

3.1. Number of Publications, Research Countries, and Institutions

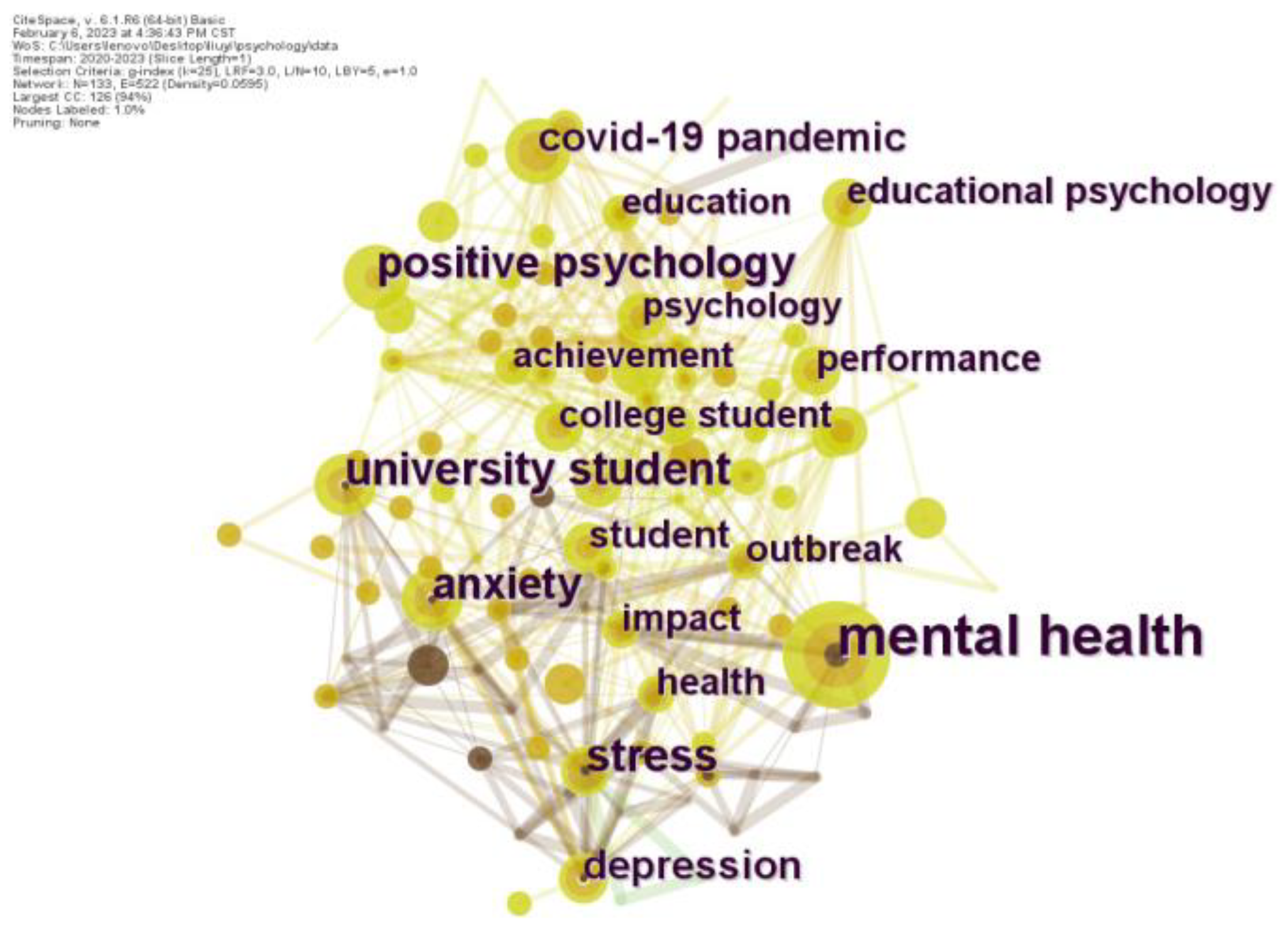

3.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence and Burst Words

3.2.1. Keyword Co-Occurrence

3.2.2. Burst Words

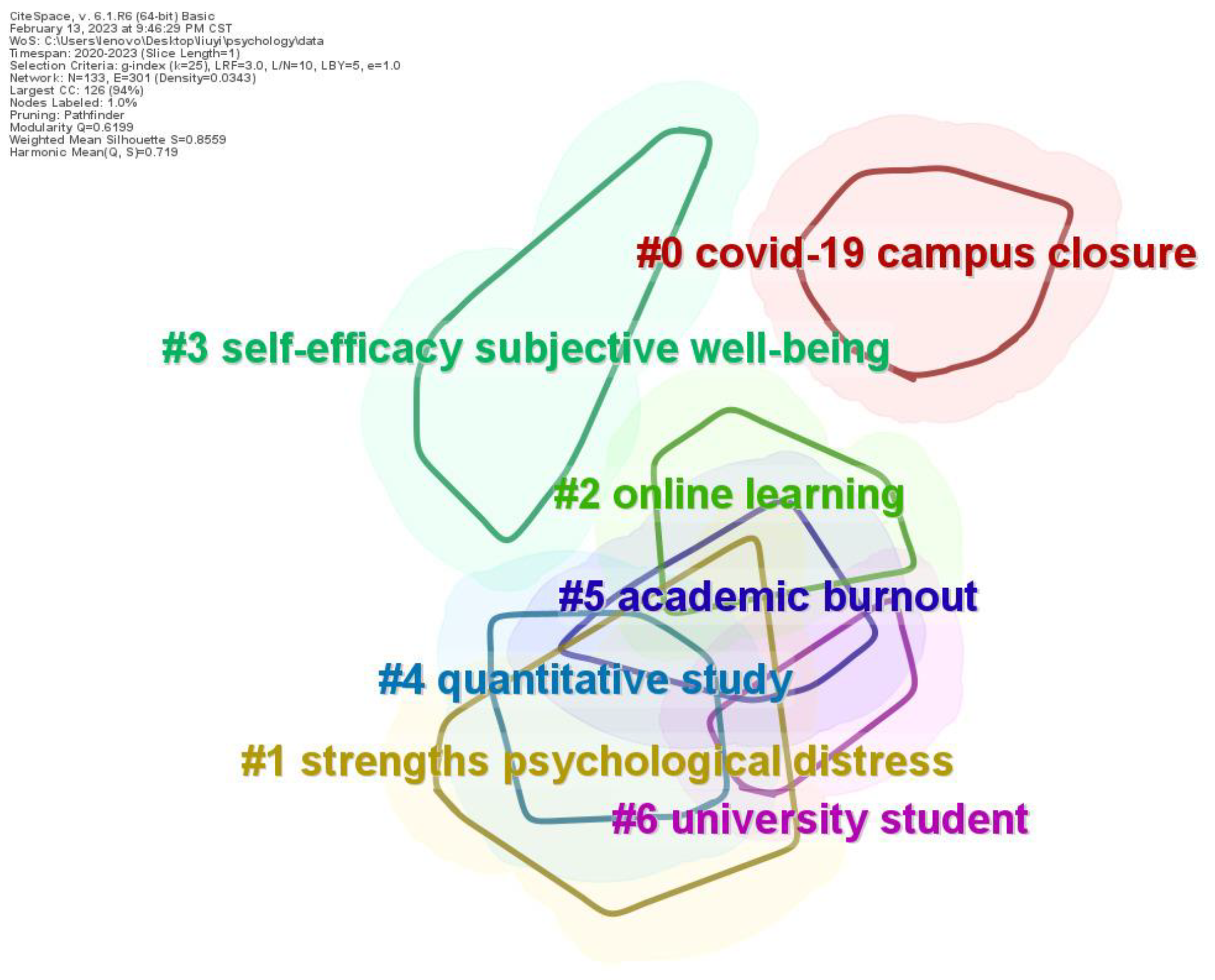

3.3. Clustering Results

4. Conclusions and Improvement Measures

4.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The learning psychology of college students in the context of COVID-19 is an area that educators have focused on, especially Chinese and American scholars. However, research institutions in this field lacked cooperation and were not closely connected.

- (2)

- Research hotspots in this field mainly have focused on mental health, positive psychology, and negative learning psychological states such as stress, anxiety, and depression. The research trend has shifted from focusing on mental health to improving academic performance.

- (3)

- Under the background of COVID-19, college students’ learning psychology was divided into three aspects: academic burnout, learning anxiety, and learning pressure.

- (4)

- Academic burnout was affected by perceived usefulness and self-control, manifested as not accepting online teaching, truancy, and an inability to concentrate on online classes.

- (5)

- Learning anxiety was affected by emotional support factors, specifically manifested as loneliness, a lack of social participation, and the fear of lockdowns and infection.

- (6)

- Learning pressure was affected by perceived ease-of-use, environmental support, and self-efficacy. It was manifested explicitly as unfamiliarity with online teaching and more difficulty in completing tasks, internet access and quiet learning places being limited, the responsibility to take care of family being greater, and uncertainty related to academic performance and future career prospects.

4.2. Improvement Measures

4.2.1. Improvement Measures for Academic Burnout

- (1)

- Flexibly arrange the content and form of online teaching, refine student categories, and enrich personalized teaching. Online education has a low sense of presence, and there is a lack of direct emotional communication between students and teachers. There is also a lack of opportunities for thinking collision between students and teachers, and psychological needs cannot be met. Therefore, the content and form of online teaching should be different from traditional classrooms. Teachers should change from “controllers” to “guides”, and students should change from “passive receivers” to “active explorers” to enhance their sense of presence in online learning. Before class, teachers can ask students to discuss and think about the relevant cases or current events in groups. During class, each group can report the data collected and discuss results, and teachers can introduce the course according to the report. After teaching basic knowledge, some questions could be set to encourage students to share new insights and cognition. The results of these classroom discussions can be taken as part of the course assessment results, and students can be allowed to accept online teaching faster and acquire knowledge through online teaching in the way of active learning. For some students with limited online learning capabilities, teachers should fully understand their difficulties and let them participate in learning in other ways. For example, books related to the course can be recommend to them and they could be allowed to learn actively in the form of course reports. An online teaching scheme could be selected according to local conditions, and a teaching mode could be selected that combines recording and broadcasting according to students’ needs. During the COVID-19 period, when students cannot access libraries to obtain paper-based learning materials, they could use smartphones, laptops, tablets, and other portable electronic devices to obtain electronic textbooks for learning so that they can constantly learn at any time and anywhere [49], which is also in line with the goal of sustainable learning, which is to impart learning strategies that are useful for all contents, anywhere, at any time [17].

- (2)

- Build real-time feedback mechanisms in the classroom, sign in regularly, and strengthen communication with students. In offline classes, teachers can constantly monitor students’ statuses, but students are often unwilling to actively participate in classroom interaction because of fear of making mistakes in public. With a screen barrier, teachers can encourage students to speak more online, and this is not limited to using a microphone to speak. Online feedback can use text, pictures, expression packs, etc., to allow students to express their views in real-time in the chat window, enhance the interaction between students and teachers, and provide the entertainment of the classroom so that they can relax and learn more and concentrate on the classroom. Of course, some rigid supervision and management measures are also necessary. Teachers can sign in any time to check whether students are doing other activities. Teachers can call the names of some students who have not interacted for a long time and interact with them to confirm whether they are present.

4.2.2. Improvement Measures for Learning Anxiety

- (1)

- Build psychological help groups, strengthen psychological communication with students, and conduct more online entertainment activities. Teachers and student cadres can set up psychological support groups to actively care about the psychological status of students in centralized isolation or in lockdowns and provide emotional support and material assistance. Isolated students communicate with the outside world more in online classes or activities. To relieve the psychological pressure on students, teachers can communicate with students before the course starts, solve problems and difficulties, talk about their problems or pressures, and respond promptly to find solutions to problems and relieve stress. In addition, online extracurricular activities with positive themes can be organized, such as online question-answering activities, online speech activities, pandemic prevention knowledge competitions, and knowledge seminars. Students could be allowed relieve their loneliness through participation in activities and large-scale online interpersonal communication, find optimism and hope in an unusual time, and meet their normal social needs.

- (2)

- Correctly guide students to obtain information about the pandemic, appease and stabilize students’ emotions in a timely manner, and actively respond. Nowadays, the online environment is complex, and students have many sources of information. Some false pandemic information can easily cause large panic in student communities. Teachers should guide students to pay attention to and use the official platforms of their country, schools, and colleges and ensure that the official media occupies the central information-giving position. The latest pandemic prevention and control knowledge, important school notice arrangements, and other information should be publicized through official platforms. In the case of an epidemic in the school’s area, it is necessary to stand up in time to stabilize students’ emotions and ensure that the students’ material needs are met. For some special situations, it is essential to have targeted and humanized solutions and respond in time to give students enough of a sense of security.

4.2.3. Improvement Measures for Learning Pressure

- (1)

- Teachers should strengthen communication with students, understand students’ living conditions, and jointly create a good online learning environment. During the pandemic, home-based isolation’s heavy and uneasy atmosphere turned the family into a battlefield of contradictions. The interference of parents, brothers, and sisters could also bring tremendous pressure on students’ studies. During the pandemic, teachers should strengthen communication with students, understand the problems they encounter in their studies and life, and provide personalized psychological pressure assistance to students. In addition, parents should be communicated with to ensure that students have a good learning environment, and parents should be urged to supervise and help.

- (2)

- Organize training and build a multi-dimensional online learning assessment mechanism. Schools started online teaching suddenly after the outbreak of the pandemic. It is necessary to improve the information literacy level of teachers and some students who have not engaged with online learning platforms before college. Teachers should help them understand how to complete exams and submit assignments online, how to review teaching through the online teaching platform, and provide corresponding technical support when they encounter problems. Online teaching cannot be assessed by only one test paper. For some students with limited online learning capabilities, even if they still pass online examinations, this will bring great pressure to their learning. It is necessary to develop an assessment mechanism that conforms to the characteristics of online teaching and carry out targeted assessments according to the situation of students. In addition to homework after class and final examinations, it is also possible to add a variety of assessment methods, such as classroom discussions, course reports, experiment reports, etc. The assessment of online teaching should not only look at results but also measure how much knowledge students have gained through online learning.

- (3)

- Guide students during graduation to clarify their career development direction. According to the national policy, teachers can provide corresponding help for students during each graduation season. First, for students who need to take a postgraduate entrance examination, students could be encouraged to participate in the postgraduate entrance examination, etc., and the channels for further study could be broadened. For example, a learning mutual aid group could be created to share learning experiences and relieve learning pressure through regular discussion. Second, for students with employment and entrepreneurship plans, alums who have successfully started businesses or companies with recruitment plans could be invited to hold online experience-sharing meetings or online job fairs to help students to find their orientation in the graduation season.

5. Contribution and Future Research Direction

5.1. Contribution

5.2. Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Husky, M.M.; Kovess-Masfety, V.; Swendsen, J.D. Stress and anxiety among university students in France during COVID-19 mandatory confinement. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogowska, A.M.; Ochnik, D.; Kusnierz, C. Revisiting the multidimensional interaction model of stress, anxiety and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivin, K.; Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E. Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 117, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essadek, A.; Gressier, F.; Krebs, T.; Corruble, E.; Falissard, B.; Rabeyron, T. Assessment of mental health of university students faced with different lockdowns during the coronavirus pandemic, a repeated cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2022, 13, 2141510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifa, I.; Hallez, Q.; van Zyl, L.E.; Braham, A.; Sahli, J.; Ben Nasr, S.; Shankland, R. Effectiveness of an online positive psychology intervention among Tunisian healthcare students on mental health and study engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Psychol.-Health Well Being 2022, 14, 1228–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.R.; Han, W.T.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Qin, W.Z.; Jing, X.; Niu, A.M.; Xu, L.Z. Network-Based Online Survey Exploring Self-Reported Depression among University and College Students during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 658388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Wu, D.J.; Burrows, B.; Mercado, E. Psychology Doctoral Program Experiences and Student Well-Being, Mental Health, and Optimism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 629205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, N.; Feraco, T.; Ghisi, M.; Meneghetti, C. “Andra tutto bene”: Associations between Character Strengths, Psychological Distress and Self-Efficacy during COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 2255–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussone, S.; Pesca, C.; Tambelli, R.; Carola, V. Psychological Health Issues Subsequent to SARS-Cov 2 Restrictive Measures: The Role of Parental Bonding and Attachment Style. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 589444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dwaikat, T.N.; Aldalaykeh, M.; Ta’an, W.; Rababa, M. The relationship between social networking sites usage and psychological distress among undergraduate students during COVID-19 lockdown. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Li, L.X.; Jiang, X.L. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on the mental health of university students in Sichuan Province, China: An online cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodriguez, F.M.; Martinez-Ramon, J.P.; Mendez, I.; Ruiz-Esteban, C. Stress, Coping, and Resilience before and after COVID-19: A Predictive Model Based on Artificial Intelligence in the University Environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, O.; Mountcastle, L.; Jehl, B.L.; Munoz-Osorio, A.; Dahlquist, L.M.; Jayasekera, A.; Dougherty, A.; Castillo, R.; Miner, K. Impact of COVID-19 Campus Closure on Undergraduates. Teach. Psychol. 2021, 0, 00986283211043924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.A.; Abu Shamsi, N.; Jenatabadi, H.S.; Ng, B.K.; Mentri, K.A.C. Factors Affecting Undergraduates’ Academic Performance during COVID-19: Fear, Stress and Teacher-Parents’ Support. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreguero, G.M.; Perera-Villalba, J.J.; Mateos-Nunez, M.; Naranjo-Correa, F.L. Development of ICT-Based Didactic Interventions for Learning Sustainability Content: Cognitive and Affective Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3644. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A. Sustainable Learning in Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horita, R.; Nishio, A.; Yamamoto, M. The effect of remote learning on the mental health of first year university students in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikova, I.A.; Bychkova, P.A.; Novikov, A.L. Attitudes towards Digital Educational Technologies among Russian University Students before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fila-Witecka, K.; Senczyszyn, A.; Kolodziejczyk, A.; Ciulkowicz, M.; Maciaszek, J.; Misiak, B.; Szczesniak, D.; Rymaszewska, J. Lifestyle Changes among Polish University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, A.L.; Holt, E.W.; Murr, S.; Falcone, K.A.; Daniel, M.; Gilchrist, A.E. University student perceptions of health and disease during remote learning in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, J.L.M.; Castano, S.C.; Santana, A.H.; Gonzalez, M.M.; Ballester, J.B. Impact of Learning in the COVID-19 Era on Academic Outcomes of Undergraduate Psychology Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8735. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.F.; Hong, X.C.; Xiao, L.H. Toward High-Quality Adult Online Learning: A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.R.; Liu, Q. Bibliometric and visualization analysis of research trend in mental health problems of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1040676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brika, S.K.M.; Chergui, K.; Algamdi, A.; Musa, A.A.; Zouaghi, R. E-Learning Research Trends in Higher Education in Light of COVID-19: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 762819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, M.; Alvarez, J.C.; Perez, E.Z.; Fernandez-Carriba, S.; Lopez, J.G. Feasibility of a Brief Online Mindfulness and Compassion-Based Intervention to Promote Mental Health among University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oker, K.; Reinhardt, M.; Schmelowszky, A. Effects of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Its Relationship with Death Attitudes and Coping Styles among Hungarian, Norwegian, and Turkish Psychology Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paechter, M.; Phan-Lesti, H.; Ertl, B.; Macher, D.; Malkoc, S.; Papousek, I. Learning in Adverse Circumstances: Impaired by Learning with Anxiety, Maladaptive Cognitions, and Emotions, but Supported by Self-Concept and Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 850578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabe-Valero, G.; Melero-Fuentes, D.; Argimon, I.I.D.; Gerbino, M. Individual Differences Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Age, Gender, Personality, and Positive Psychology. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telyani, A.E.; Farmanesh, P.; Zargar, P. The Impact of COVID-19 Instigated Changes on Loneliness of Teachers and Motivation-Engagement of Students: A Psychological Analysis of Education Sector. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 765180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, M.; Bradley, A.; Playfoot, D.; Harrad, R. Personality traits and stress perception as predictors of students’ online engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 194, 111645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamthan, P. The Experience of Tests during the COVID-19 Pandemic-Induced Emergency Remote Teaching. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2022, 32, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, Y.H. A Positive Psychology Perspective on Positive Emotion and Foreign Language Enjoyment among Chinese as a Second Language Learners Attending Virtual Online Classes in the Emergency Remote Teaching Context Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 798650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirekin, Z.B.; Buyukcavus, M.H. Effect of distance learning on the quality of life, anxiety and stress levels of dental students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, S.; Qiao, Y.; Yan, X.; Anwar, A.; Hao, T.Y.; Rana, S. Digital Students’ Satisfaction with and Intention to Use Online Teaching Modes, Role of Big Five Personality Traits. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 956281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Analysis of the Current Situation of the Research on the Influencing Factors of Online Learning Behavior and Suggestions for Teaching Improvement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, A.; Flett, G.L.; Nepon, T.; Zeigler-Hill, V. Personality, Cognition, and Adaptability to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations with Loneliness, Distress, and Positive and Negative Mood States. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 971–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosselmann, V.; Amatriain-Fernandez, S.; Gronwald, T.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; Machado, S.; Budde, H. Physical Activity, Boredom and Fear of COVID-19 among Adolescents in Germany. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Chinna, K.; Kamaludin, K.; Nurunnabi, M.; Baloch, G.M.; Khoshaim, H.B.; Hossain, S.F.A.; Sukayt, A. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown among University Students in Malaysia: Implications and Policy Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, A.; Valido, A.; Woolweaver, A.B.; Espelage, D.L. Teacher Concern During COVID-19: Associations with Classroom Climate. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Shah, A.A.; Memon, F.; Kemal, A.A.; Soomro, A. Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Applying the self-determination theory in the ‘new normal’. Rev. Psicodidact. 2021, 26, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckley, D.; Allen, A.; Millear, P.; Rune, K.T. COVID-19’s impact on learning processes in Australian university students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 26, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meji, M.A.; Dennison, M.S. Survey on general awareness, mental state and academic difficulties among students due to COVID-19 outbreak in the western regions of Uganda. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05454. [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Canadas, G.R.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Pradas-Hernandez, L.; Martos-Cabrera, B.; Velando-Soriano, A.; de la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Levels of Burnout and Engagement after COVID-19 among Psychology and Nursing Students in Spain: A Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.L.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, R.Q. Classroom Digital Teaching and College Students’ Academic Burnout in the Post COVID-19 Era: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, M.; Albert, C.N.; Mihai, V.C.; Dumitras, D.E. Emotional and Social Engagement in the English Language Classroom for Higher Education Students in the COVID-19 Online Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, T.T.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.L.; Sun, X.H.; Li, S.J. Parental marital conflict, negative emotions, phubbing, and academic burnout among college students in the postpandemic era: A multiple mediating models. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 60, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.K.; Lo, C.K. Flipped Classroom and Gamification Approach: Its Impact on Performance and Academic Commitment on Sustainable Learning in Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muca, E.; Cavallini, D.; Odore, R.; Baratta, M.; Bergero, D.; Valle, E. Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Han, Y. Exploring Chinese EFL Learners’ Achievement Emotions and Their Antecedents in an Online English Learning Environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chotipanvithayakul, R.; Wichaidit, W.; Cai, W. Effects of Character Strength-Based Intervention vs Group Counseling on Post-Traumatic Growth, Well-Being, and Depression Among University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Guangdong, China: A Non-Inferiority Trial. Psychol Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alvarez, D.; Soler, M.J.; Cobo-Rendon, R.; Hernandez-Lalinde, J. Positive Psychology Applied to Education in Practicing Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Personal Resources, Well-Being, and Teacher Training. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Ruan, X.M.; Feng, Z.R.; Jiang, P.J. Teachers’ Perceptions of Online Teaching Do Not Differ across Disciplines: A Survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Country | Number | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 28 | 0.22 |

| 2 | USA | 20 | 0.11 |

| 3 | Spain | 9 | 0.19 |

| Rank | Institution | Number | Centrality |

| 1 | University of Granada | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | University of Melbourne | 2 | 0 |

| University of Massachusetts | 2 | 0 | |

| Prince Sultan University | 2 | 0 | |

| IUBAT—International University of Business Agriculture and Technology | 2 | 0 | |

| Monash University | 2 | 0 | |

| University Toronto | 2 | 0 | |

| Central China Normal University | 2 | 0 | |

| University of Pennsylvania | 2 | 0 | |

| California State University Monterey Bay | 2 | 0 | |

| Minzu University of China | 2 | 0 |

| Rank | Keyword | Frequency | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mental health | 35 | 0.15 |

| 2 | university student | 16 | 0.12 |

| stress | 16 | 0.17 | |

| 3 | anxiety | 14 | 0.07 |

| 4 | positive psychology | 13 | 0.01 |

| 5 | depression | 12 | 0.09 |

| 6 | COVID-19 pandemic | 11 | 0.02 |

| 7 | student | 10 | 0.04 |

| 8 | outbreak | 9 | 0.03 |

| 9 | health | 8 | 0.14 |

| educational psychology | 8 | 0.06 | |

| college student | 8 | 0.07 | |

| impact | 8 | 0.05 | |

| performance | 8 | 0.05 | |

| 10 | achievement | 7 | 0.04 |

| education | 7 | 0.12 | |

| psychology | 7 | 0.05 |

| Learning Psychology | Specific Performance | Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Academic burnout | Not accepting online teaching [34,35]. | Perceived usefulness |

| Truancy and cannot concentrate on online classes [36]. | Self-control | |

| Learning anxiety | Feeling lonely and lacking social participation [11,37]. | Emotional support |

| Concern and fear of lockdown and infection [12,38]. | ||

| Learning pressure | Not familiar with online learning and more difficult to complete tasks [14]. | Perceived ease-of-use |

| Internet access and quiet learning places are limited and the responsibility to take care of family is greater [10,14]. | Environmental support | |

| Uncertainly related to academic performance and future career prospects [39]. | Self-efficacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Li, Z. International Research Review and Teaching Improvement Measures of College Students’ Learning Psychology under the Background of COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097459

Liu Y, Li Z. International Research Review and Teaching Improvement Measures of College Students’ Learning Psychology under the Background of COVID-19. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097459

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yi, and Zhigang Li. 2023. "International Research Review and Teaching Improvement Measures of College Students’ Learning Psychology under the Background of COVID-19" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097459

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Li, Z. (2023). International Research Review and Teaching Improvement Measures of College Students’ Learning Psychology under the Background of COVID-19. Sustainability, 15(9), 7459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097459