Abstract

Although the relationships between managerial practices and work-related outcomes are contingent on leadership behaviors, little scholarly attention has been paid to how leadership styles shape the impact of distributive justice and goal clarity on employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the field of organizational behavior and management. In this context, this study examines the direct effects of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB based on two motivation theories, equity theory and goal-setting theory, as well as the moderating role of transactional and transformational leadership in the relationships based on social exchange theory. Using survey data from a sample of 4133 public employees drawn from Korean central and local governments and ordinary least square regression models, we found that distributive justice is negatively related to OCB, whereas goal clarity is positively related to OCB. Further analysis shows that while transactional leadership weakens the negative relationship between distributive justice and OCB, transformational leadership strengthens the positive relationship between goal clarity and OCB. Consequently, our study provides meaningful implications for public managers and organizations that should be considered in order to implement effective managerial practices based on the fitness between employee motivation processes and leadership styles to encourage employees to exhibit OCB. This will enhance organizational performance and sustainability.

1. Introduction

Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) has been one of the most extensively researched areas in the field of organizational behavior and management over the past three decades [1,2]. Citizenship behaviors are employees’ extra-role behaviors whereby they perform beyond expectations in terms of their formal job descriptions [3]. Such behavior includes, for example, knowledge sharing, helping colleagues, protecting the organization, and speaking up about crucial organizational issues [4,5,6]. Given that citizens not only expect public organizations to provide more services and policies of higher quality but also to actively address various social problems [7], these extra-role behaviors have received considerable scholarly attention because of their contribution to organizational performance and sustainability [8]. Therefore, it is not surprising that many researchers and practitioners have sought to determine what organizational factors induce employees to engage in OCB and to provide empirical evidence that varied managerial practices, such as organizational rules, employee empowerment, and merit promotion, have significant influence on employee OCB [2,3].

Despite growing scholarly attention to managing employee OCB, very little empirical research has examined how two managerial practices—distributive justice and goal clarity—shape extra-role behaviors in public-sector organizations. Two motivational theories provide a particularly useful lens for unraveling distributive justice–OCB and goal clarity–OCB relationships [9,10]. Based on equity theory, employees who perceive an equal ratio of outcomes (e.g., pay and promotion) to inputs (e.g., skills and effort) are more likely to exhibit OCB due to a sense of comfort caused by this perception of fair outcome distribution [9]. Moreover, drawing from goal-setting theory, employees who clearly recognize what they must do to achieve organizational goals have high levels of goal commitment that motivate them to engage in OCB [10]. Using these theoretical perspectives, we assume that distributive justice and goal clarity are positively associated with employee OCB.

However, distributive justice and goal clarity do not exist independently in a vacuum but interact with various leadership styles in shaping OCB [11]. In this respect, considering that leaders exert great influence on employees’ behaviors, Lai et al. ([12], p. 430) argue that “it is reasonable to consider leaders’ leadership style as a moderator that fosters or hinders employees’ behaviors”. Of particular interest is how transactional and transformational leadership as significant moderators condition the effects of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB, as leadership behaviors enhance followers’ motivation by developing a social atmosphere with an interpersonal context [13,14]. According to social exchange theory, the two leadership styles may strengthen the positive impact of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB by leading employees to feel a sense of obligation to reciprocate toward their leaders in the form of positive work behaviors [15,16]. Building on this theoretical perspective, we propose that transactional leadership intensifies the positive association between distributive justice and OCB by strengthening the economic exchange relationship with followers, whereas transformational leadership enhances the positive association between goal clarity and OCB through forming a stronger social exchange relationship with followers [17].

In summary, although some progress has been made, we still lack a comprehensive empirical understanding of whether distributive justice and goal clarity are significant predictors of OCB. Indeed, one cannot find as much relevant empirical research on this topic in the field of public management as in the field of business management. That is, understanding the relationships of distributive justice and goal clarity with OCB and the various human resource management practices and leadership styles used to manage the relationships still poses major challenges to public administration scholars and practitioners. Furthermore, Badura and colleagues [18] called for bridging the motivation and leadership literature to advance theory in terms of the mechanism through which certain leadership styles are congruent with different managerial practices. This means that fitness between certain leadership styles and managerial practices may contribute to employee OCB. However, surprisingly few studies have tried to synthesize motivation and leadership theories to investigate how transactional and transformational leadership shape the impact of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB. Therefore, we seek to answer two research questions: (1) Do distributive justice and goal clarity in public sector organizations have positive relationships with employee OCB? (2) How are these relationships moderated by transactional and transformational leadership? By doing so, this article advances the existing knowledge of how to promote employee OCB in public sector organizations.

In the next section, we review the relevant literature and the theoretical bases supporting the study’s hypotheses. Subsequently, the data and variables used for the model are outlined, and the findings are described. Finally, we conclude with an assessment of the implications of the results for public managers and organizations.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Distributive Justice, Goal Clarity, and OCB

Scholars have long contended that employee performance is measured by more than just how well employees carry out the work and responsibilities formally assigned to them by their organization [2,3,7]. However, it is also essential for employees to engage in OCB to increase organizational sustainability and effectiveness, even when these behaviors are not directly recognized by the organization’s formal reward system [9,19]. OCB consists of five complementary forms of citizenship—altruism (i.e., voluntarily assisting coworkers), conscientiousness (i.e., a sense of respect for organizational resources), courtesy (i.e., preventing interpersonal problems), civic virtue (i.e., constructive participation in organizational meetings), and sportsmanship (i.e., willingness to respectfully tolerate organizational settings without complaint) [20]. Such voluntary, extra-role behaviors contribute to organizational functioning and performance [8]; therefore, this study explores what organizational factors lead to employee OCB.

Many scholars in the field of organizational behavior and management suggest that one way to encourage employees to exhibit extra-role work behaviors that benefit the organization is to motivate them through human resource management practices [21,22,23]. Work motivation refers to the psychological process that determines the intensity (force), persistence (duration), and direction (relevance) of an employee’s effortful behavior [24,25]. Given that work motivation is a key factor in encouraging employees to demonstrate desirable work behaviors, many researchers have sought to understand the theoretical mechanisms through which employees are motivated at work [21]. Among many motivational perspectives, equity theory and goal-setting theory are the most widely used to determine which organizational policies and work environments are efficient in encouraging employees to exhibit OCB [26]. This study relies on two types of human resource management, distributive justice related to equity theory and goal clarity related to goal-setting theory, as antecedents of employee OCB.

Distributive justice refers to the perceived fairness of rewards one receives from an organization [27,28]. According to equity theory [29], employees psychologically compare the ratios of their inputs (e.g., work effort and education) and outcomes (e.g., pay and benefits) to the perceived ratios of referent others. Specifically, they feel a sense of equity (distributive justice) when they perceive that their outcome-to-input ratio is proportionally matched to that of the referent party [30]. Conversely, employees feel that the organization has treated them unfairly in terms of outcome allocation when their ratio is perceived to be either smaller than the negative equity or larger than the positive equity of the referent party [29,30]. More importantly, employees always try to restore equity by altering their own inputs and outcomes or those of others [31,32]. For instance, they reduce their inputs in a situation of negative equity to balance the perceived input/outcome ratio and fairness of reward distribution. In other words, when employees feel they do not receive fair compensation from their organization, they engage in negative work-related actions, such as interpersonal conflict, aggression, and absenteeism [33]. That is, employees are less likely to engage in OCB due to their perception of unfair outcome distribution [34].

In support of this rationale, previous studies have indicated that distributive justice is negatively associated with employee OCB. For example, Karriker and Williams [19] found that employees with high levels of distributive justice perception in the US reported greater OCB than those with low levels. These findings support the notion that if employees perceive fair compensation, then they may be more likely to engage in OCB because such behavior is spontaneous, going beyond an employee’s formal role requirements. Similarly, Chen and Jin [35] provided evidence that employees who perceive receiving fair rewards in the Chinese context engage in extra-role behavior that promotes effective functioning of the organization. This result implies that the fair distribution of extrinsic rewards (i.e., outcomes proportional to inputs) is a powerful predictor of OCB [9]. Specifically, distributive justice plays a role in developing employee trust in an organization and thus motivates employees to exhibit discretionary work behaviors that increase organization effectiveness. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

Distributive justice is positively associated with OCB.

Goal-setting theory argues that organizational goal clarity is a strong predictor of OCB. Goal clarity has been defined as the extent to which organizational goals or objectives are clearly stated and well-defined [36]. Based on the goal-setting theory suggested by Locke and Latham [37], organizational goals play a crucial role in motivational factors that regulate work attitudes and behaviors [38]. That is, specific goals motivate employees to achieve higher job performance than ambiguous goals [39]. If employees better understand what is expected of them, then the work attitudes and behaviors they should adopt to attain organizational goals become clearer. Correspondingly, the likelihood that they will accomplish their goals increases [40]. In this respect, Vigoda-Gadot and Angert [41] posit that the achievement of specified goals may lead to satisfying an employee’s desires for growth and affiliation, which in turn encourages employees to achieve above the required performance levels. Stated differently, employees with high levels of goal clarity experience pleasure at work and therefore become more willing to exhibit extra-role behaviors [41].

Corroborating the tenet of goal-setting theory, several studies have revealed a positive relationship between goal clarity and OCB. For instance, Caillier [42] found that public employees in the US who understand exactly how their tasks relate to the purpose of the organization are likely to exhibit extra-role behaviors, such as volunteering for tasks that are not required, making suggestions to improve the organization, and investing significant effort beyond what is normally expected. In addition, Taylor [10] found that goal specificity has a positive influence on the OCB of government employees in Australia. Similarly, empirical research conducted by Ritz et al. (2014) revealed that public managers at the Swiss municipal level who have a sense of organizational goal clarification engage in positive, beneficial actions directed at their colleagues and organization. These previous findings suggest that clear organizational goals encourage employees to engage in extra-role behaviors because goal clarity allows them to view organizational goals as congruent with their own personal values [43]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Goal clarity is positively associated with OCB.

2.2. Moderating Effects of Leadership Styles

Leadership is the dynamic process by which a leader influences followers’ work attitudes and behaviors to increase organizational performance [11,12]. Researchers of leadership styles have paid considerable attention to how to promote employee work behaviors that benefit the employer organization [44,45,46]. The Full Range of Leadership Model (FRLM) has been one of the major theoretical perspectives used to explain the organizational consequences of leadership styles in public management [47,48]. However, there is no single leadership style that best fits all organizational contexts [49]. Hence, leadership effectiveness is contingent on managerial practices that shape employee work-related outcomes [50]. Applying this logic to the current study, the effects of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB could differ depending on leadership styles. Therefore, we explore how the two leadership styles suggested by the FRLM—transactional and transformational leadership—moderate the impact of distributive justice and goal clarity on employee OCB.

Transactional leadership focuses on a series of negotiated exchanges between a leader and a follower in which the leader offers rewards in return for the follower’s performance [51]. This leadership style comprises two behavioral aspects, contingent reward and management by exception [52]. A contingent reward is a crucial component of transactional leadership because it motivates followers by setting expectations for them that define what level of performance they should achieve and rewarding their performance [53]. Leadership scholars argue that followers formulate positive relationships with managers through transactional leadership, as managers control the allocation of desired tangible outcomes, including pay and promotion [52,54]. The preference for rewards in this reward-oriented relationship increases a follower’s interest in engaging in the exchange process [55]. Transactional leaders show management by exception as a corrective action that prevents followers from deviating from contracts and normative standards [56]. Transactional leadership focuses on the routine monitoring of followers’ work behaviors to ensure that they meet performance standards. Followers may perceive management by exception as managerial support of transactional leaders in that corrective actions and monitoring provide more efficient ways to improve job performance [57,58].

As another leadership style of the FRLM, transformational leadership is “the process of influencing major changes in the attitudes and assumptions of organization members and building commitment for the organization’s mission, objectives, and strategies” ([50], p. 269). Bass and Avolio [59] posit that transformational leadership consists of four behavioral dimensions—idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Idealized influence refers to a leader’s behaviors, such as being a charismatic role model who gives followers confidence in their capacity to attain organizational goals and who sacrifices their self-interest for the sake of the organization [56]. The inspirational motivation of transformational leaders is characterized by creating an appealing vision of the organization and encouraging followers to commit to achieving the organizational goals [60]. Intellectual stimulation involves a leader’s behaviors that prompt followers to be creative in seeking new solutions to problems and striving to attain challenging goals [56]. Individualized consideration means that transformational leaders help followers develop their potential by providing a supportive organizational climate and paying special attention to followers’ personal need for growth [53].

Social exchange theory provides a useful theoretical lens for explaining how the two leadership styles moderate the impact of transactional and transformational leadership on employee OCB [61]. In his seminal work, Blau [62] categorized the exchange relationship between followers and leaders as a socioeconomic form of exchange. Economic exchange is transactional in that it emphasizes the exchange of specified short-term contracts and materialistic, impersonal resources, such as monetary incentives and pay raises, whereas social exchange involves a long-term orientation and exchange of socioemotional resources, including trust and respect [63]. The two exchange relationships lead employees to feel an obligation to reciprocate in the form of positive work-related outcomes. For example, Walumbwa, Cropanzano, and Hartnell [15] argued that employees involved in economic exchanges are reciprocal in that they repay their leaders for tangible rewards rendered. If these exchange relationships continue and allow employees to be happy with the rewards, then they become more trusting of leaders and more likely to exhibit OCB [15,64]. In a similar vein, employees involved in social exchanges feel a greater obligation for receiving the leader’s support (e.g., consideration, career development, mentoring, and support for innovation) and exhibit productive work behaviors that are beneficial to the organization.

Given that the norms of reciprocity resulting from economic exchanges rely on calculus-based trust and extrinsic rewards, distributive justice may fit transactional leadership [65]. Accordingly, it is plausible that transactional leadership where leaders induce their followers’ desirable behaviors through compensation and corrective actions strengthens the negative relationship between distributive justice and OCB. If transactional leaders clearly inform followers of task conditions, performance criteria, and monetary rewards and followers perceive distributional justice as highly as their contributions to the organization, they are likely to repay their leaders for benefits in the form of extra-role behaviors that benefit the organization. That is, followers with high levels of distributive justice have high expectations for the outcome allocation corresponding to the performance they achieved. This expectation promotes employee OCB in situations where transactional leadership is strongly exercised. Indeed, several empirical studies have offered evidence that transactional leadership may strengthen the positive relationship between distributive justice and OCB. For example, Vieira, Perin, and Sampaio provided evidence that transactional leadership enhances the positive influence of sales employees’ self-efficacy on work-related outcomes, such as loyalty and job satisfaction, in the context of department stores in Brazil. In a similar vein, using a large-scale survey of managers of US firms, Du et al. [66] found that transactional leadership amplifies the positive association between institutional corporate social responsibility practices (e.g., financial support for education and culture in local communities) and organizational performance. Consequently, these findings suggest that transactional leadership is more likely to motivate followers with high levels of distributive justice to engage in OCB because transactional leadership fits with distributive justice in that job performance serves as a “tangible quid pro quo for pay” ([66], p. 1010). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

The positive relationship between distributive justice and OCB is moderated by transactional leadership such that the relationship is much stronger when transactional leadership is higher rather than lower.

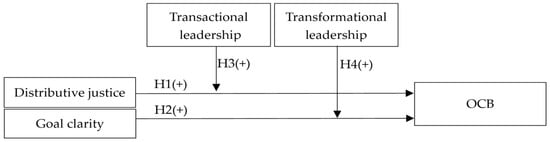

In contrast to transactional leadership characterized by the economic exchange relationship between leaders and followers, we predict that transformational leadership may augment the negative relationship between goal clarity and OCB by forming reciprocal social exchange relationships with followers. Goal clarity motivates employees to achieve organizational goals; if transformational leaders communicate compelling visions and goals to their followers, promote followers’ creative thinking, and genuinely care about followers’ growth, followers with high levels of goal clarity should increase their goal commitment and are therefore more likely to reciprocate with positive behaviors such as OCBs to benefit the organization [67,68,69]. This means that the social relationship between leaders and followers formed by transformational leadership may amplify the effect of motivation induced by goal clarity. Although there is little evidence regarding the moderating effect of transformational leadership on the goal clarity–OCB link, similar previous studies are useful to anticipate how transformational leadership shapes the impact of goal clarity on OCB. For example, in the context of the Australian local government, Muchiri and Ayoko [70] found that demographic diversity related negatively to OCB because of relational conflict caused by the heterogeneity of individual attributes (e.g., gender and tenure) within a group. However, when moderated by transformational leadership the negative impact of demographic diversity on OCB was alleviated. This is because the four behaviors of transformational leaders motivate demographically diverse employees to reciprocate by engaging in OCB. Wang and Walumbwa [61] found that banking sector employees with family-friendly benefits are more likely to be committed to their organizations but less likely to show work withdrawal when their leaders practice transformational leadership. That study suggests that transformational leadership enhances the positive impact of family-friendly benefits on organizational commitment and the negative impact on work withdrawal by allowing employees to feel obligated to show positive work attitudes and behaviors in return for the benefits. Based on these arguments and previous empirical evidence, the following hypothesis will be explored (Figure 1 shows the hypothesized model):

Hypothesis 4.

The positive relationship between goal clarity and OCB is moderated by transformational leadership, such that the relationship is much stronger when transformational leadership is higher rather than lower.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

To test the hypotheses, we used the cross-sectional data from the Korean Public Employee Viewpoints Survey (PEVS) conducted by the Korea Institute of Public Administration (KIPA) from 12 August to 30 September 2021. KIPA is one of the representative national research institutes supported by the Korean central government and studies issues relating to public administration and policy. The PEVS, which contains official and confidential data, was accredited by the National Statistical Office, and therefore many public administration scholars use it in their research [7]. The survey targeted general-service public employees from 46 executive agencies in the central government and all 17 regional metropolitan governments. Considering that the Korean public sector has recently sought to motivate employees to show OCB as a way of increasing organizational performance [7], PEVS data containing information about public employees’ perceptions of human resource management practices and the unique working context of the Korean government are pertinent to test the hypotheses proposed in this study [71]. Using a stratified two-stage cluster sampling procedure, KIPA randomly selected 600 teams at the first stage and finally yielded a total of 4133 respondents, including 2092 from executive agencies and 2041 from regional metropolitan governments at the second stage. It should be noted that the survey relied on two methods to reduce nonresponse bias. First, it used the weights of survey respondents based on demographic characteristics, such as gender and job grades, to ensure that the full population of public employees in the central and metropolitan governments was considered by allowing each employee to have the same probability of being selected as a survey respondent. Second, respondents were assured that their responses would be kept confidential. Thus, respondents’ privacy was protected, and they were not compelled to provide desirable responses. Table 1 shows the detailed background descriptions of the respondents.

Table 1.

Sample by demographic information.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: OCB

According to Podsakoff and MacKenzie [72], OCB refers to discretionary, extra-role behaviors that go beyond the expectations of the job and job description and includes altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, conscientiousness, and civic virtue. Based on this definition, five items were used to measure OCB: (1) “I help my colleagues who are absent or have heavy workloads” (altruism), (2) “I attend and actively participate in organizational meetings” (civic virtue), (3) “I listen attentively to my colleagues’ problems and concerns” (courtesy), (4) “I look after the equipment of my organization as if I own it” (conscientiousness), and (5) “I try to solve problems by talking directly to my colleagues rather than gossiping behind the scenes when I have a complaint about them” (sportsmanship).

3.2.2. Independent Variables: Distributive Justice and Goal Clarity

The concept of distributive justice centers on the perceived fairness of the amount of rewards an employee receives from their organization [73]. We measured distributive justice with four items adapted from [74]: (1) “my pay level is appropriate given my job performance”, (2) “my pay level is appropriate compared with those in the private sector (such as large corporations) who perform comparable tasks”, (3) “I am justly compensated given the degree of job difficulty”, and (4) “I am justly compensated given my job responsibilities.” Goal clarity is defined as the extent to which organizational goals are indicated clearly and specifically, and it is easy for employees to understand how to achieve those goals [75,76]. We measured goal clarity with four items adapted from [77]: (1) “I am clearly aware of the organizational goals of my agency”, (2) “the priority between organizational goals is clear in my agency”, (3) “the organizational goals of my agency provide clear guidelines for work performance”, and (4) “my agency can objectively measure the degree of goal achievement over the past year”.

3.2.3. Moderating Variables: Transactional and Transformational Leadership

Transactional leadership refers to a leader’s behavior in motivating followers through an exchange process involving tangible rewards, rules, and requirements [78,79]. We used three items to measure two components of transactional leadership, contingent rewards, and management by exception: (1) “my supervisor makes clear what I can expect to receive when performance goals are achieved” (contingent rewards), (2) “my supervisor gives me specific instructions about what I have to do to receive rewards for my job performance” (contingent rewards), and (3) “my supervisor regularly provides me with feedback about my performance” (management by exception). According to Bass [52], transformational leadership consists of four components—idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Four items were used to measure transformational leadership: (1) “my supervisor provides me with a clear vision of the direction I need to take” (inspirational motivation), (2) “my supervisor motivates me to work hard” (idealized influence), (3) “my supervisor encourages me to perform my work by incorporating new perspectives” (intellectual stimulation), and (4) “my supervisor helps me pursue my own development” (individualized consideration).

3.2.4. Control Variables

The study controlled for job satisfaction and several personal characteristics of the respondents that may affect OCB. According to Organ and Konovsky [80], job satisfaction is a powerful predictor of OCB because employees who feel a sense of well-being at work are likely to engage in voluntary and discretionary behaviors that are beneficial to organizational performance, even if their behaviors are not formally rewarded by the organization. A single survey item measured employees’ job satisfaction: “I am satisfied with my job regardless of rewards received from the organization.” We also included employees’ demographic characteristics as control variables: gender (1 = female, 0 = male), age (1 = 20–29, 2 = 30–39, 3 = 40–49, 4 = 50 or older), education level (1 = high school, 2 = college, 3 = bachelor’s degree, 4 = graduate school), job grade (1 = grades 1–4, 2 = grade 5, 3 = grades 6−7, 4 = grades 8−9), tenure (1 = less than 5 years, 2 = 6–10 years, 3 = 11–15 years, 4 = 16–20 years, 5 = 21–25 years, 6 = more than 26 years), and government level (local = 1, central = 0).

3.3. Measurement Reliability and Validity

We estimated the validity of the scale measures and the latent variables they represented in several ways. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test convergent and discriminant validity. As shown in Table 2, the hypothesized five-factor model (OCB, transactional leadership, transformational leadership, distributive justice, and goal clarity) fit the data well. The results showed that the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which should be lower than 0.08, were 0.07 and 0.03, respectively, and the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), which should generally be above 0.90, were 0.97 and 0.96, respectively. This supported the discriminant validity of the latent variables. In addition, the factor loadings of all items exceeded 0.50 (ranging from 0.60 to 0.93) and were significant. Second, the composite construct reliability of all latent variables was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The results showed that the composite reliability of all the latent variables is above the recommended threshold of 0.7 [81]. Third, except for OCB, for which the average variance extracted (AVE) was slightly below the threshold of 0.5, the AVE values of all the latent variables were clearly above 0.5. However, the Cronbach’s of OCB, another criterion, was 0.779, which exceeded the acceptance level of 0.7. Thus, we conclude that the measurement of OCB demonstrated convergent validity [82]. Table 3 presents the standardized factor loadings, Cronbach’s α, and AVE for all the latent variables. Finally, Harman’s single-factor test was used to determine common method variance (CMV), which may exist when all variables are collected from the same data source and which may inflate the association between variables. The results revealed that the main explanatory factor accounted for only 39% of the covariance among the measures, less than the common threshold (50%). Consequently, CMV may not be a serious concern in the current study.

Table 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analyses.

Table 3.

Factor loadings, Cronbach’s α, and AVE for all latent variables.

4. Results

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations for the variables. All the correlations between the main independent variables were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level and in the expected direction. Of the control variables, gender, age, tenure, job grade, and education were significantly associated with innovative behavior. The correlation coefficients provided preliminary support for our research hypotheses.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

We relied on the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model and STATA 17 statistical software to test our hypotheses because the dependent variable was summed averages. The analysis was performed in three steps. First, we provide a baseline model in which all control variables and moderating variables are included. Second, we report the main effects of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB. Finally, we show how the two leadership styles moderate the associations between distributive justice and OCB and between goal clarity and OCB.

Table 5 shows the statistical results of the models. First, the results of Model 1 report that some control variables and moderating variables were significantly related to the dependent variable. Specifically, employee education had a positive impact on OCB ( = −0.026; p < 0.05). It may be plausible that employees with a higher level of education have considerable task-related knowledge to share with their colleagues and a greater ability to make innovative suggestions to improve their organization compared to those with a lower level of education. Regarding the government level ( = −0.045; p < 0.05), employees who work in the central government are less likely to exhibit OCB than those who work in the local government. It may be possible that central government employees have greater workloads and greater work intensity than local government employees and therefore exhibit fewer extra-role behaviors. The results show that job satisfaction was positively associated with OCB ( = 0.346; p < 0.01). It is possible that employees who are satisfied with their job are more likely to reciprocate with positive behavior including voluntary and discretionary behaviors that contribute to organizational performance [80]. In terms of moderating variables, both transactional ( = 0.126; p < 0.01) and transformational leadership ( = 0.068; p < 0.01) were significantly and positively associated with employee OCB. As discussed above, transactional leadership is characterized by linking organizational rewards, including pay and benefits, with the level of task performance that employees achieve. This feature of transactional leadership allows employees to feel a sense of organizational support, which may lead to OCB [83]. The four behaviors of transformational leaders are likely to encourage employees to engage in extra-role behaviors by offering attractive and compelling goals for organizational sustainability [84].

Table 5.

OLS regression results.

Model 2 indicates that distributive justice ( = −0.049; p < 0.01) had a significant and negative impact on OCB, which does not support hypothesis 1 that distributive justice is positively associated with OCB. This finding is somewhat surprising and counterintuitive because we predicted that the perceived fairness of organizational outcomes serves as a powerful motive that encourages employees to exhibit OCB. This unexpected finding can be explained by the motivation crowding-out effect. In general, public employees have stronger intrinsic motivation characterized by the pure enjoyment of performing work itself than extrinsic motivation centered on economic compensation. However, excessive emphasis on distributive justice by providing material compensation according to employee performance levels in such a situation may undermine intrinsic motivation and eventually decrease employee OCB.

In terms of the goal clarity–OCB link, the results show that goal clarity had a significant and positive influence on OCB, which is consistent with goal clarity being positively associated with OCB. This finding implies that clear organizational goals are strong sources of employee motivation that lead employees to engage in extra-role behaviors that extend beyond what is formally required in their jobs.

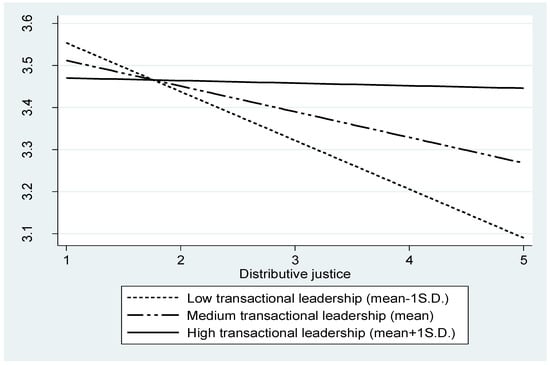

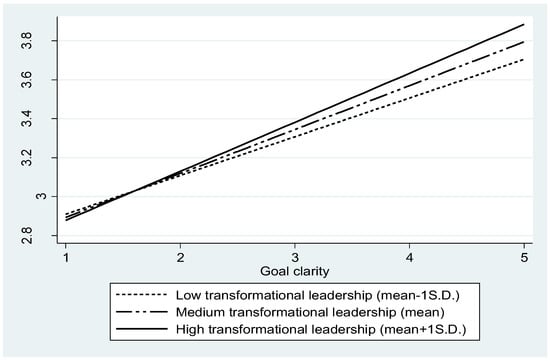

We added the interaction terms DJ TAL ( = 0.071; p < 0.01) and GC TFL ( = 0.033; p < 0.05) to Model 3 to better explore the integrative framework of motivation and leadership theories. The results revealed that transactional leadership diminished the negative relationship between distributive justice and OCB, which is consistent with hypothesis 3. One explanation for this result is that high congruence between distributive justice emphasizing a performance-oriented compensation system and transactional leadership characterized by the economic exchange relationship mitigates the negative effect of distributive justice on employee OCB. Furthermore, the results indicate that transformation leadership enhanced the positive relationship between goal clarity and OCB, supporting hypothesis 4. Employees who perceive goal clarity are more likely to engage in OCB because they feel obligated to repay their transformational leaders by exhibiting prosocial work behaviors that go beyond formal occupational requirements.

To better understand the nature of the interaction effects of the two leadership styles, we visualized how the distributive justice–OCB and goal clarity–OCB relationships change depending on the levels of transactional and transformational leadership. Figure 2 shows that compared to employees who experience low transactional leadership (defined as one standard deviation below the mean indicated by the dashed line), employees who experience high transactional leadership (defined as one standard deviation above the mean indicated by the solid line) are likely to engage in OCB. Figure 3 shows that with high transformational leadership effectiveness, the positive impact of goal clarity on OCB strengthens.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect of distributive justice and transactional leadership on employee OCB.

Figure 3.

Interaction effect of goal clarity and transformational leadership on employee OCB.

5. Discussion

Given that inducing employees to engage in OCB that contributes to organizational sustainability has long been a central issue in the field of organizational behavior and management, many scholars have examined the relationships between the various human resource management practices and OCB. However, unlike previous studies, our study explored the impact of two managerial practices—distributive justice and goal clarity—on OCB based on equity theory and goal-setting theory. Furthermore, this study delved into the two leadership styles—transactional and transformational—as moderators of the relationships between the two managerial practices and OCB, building on social exchange theory. In the following, we discuss several important implications of our findings for research and practice.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Despite the recent growth of scholarly interest in the organizational consequences of distributive justice and goal clarity, few empirical studies have examined how the two types of managerial practices shape employee OCB. Furthermore, many leadership scholars have argued that leadership styles are contingency factors in the relationships between managerial practices and work-related outcomes. In this study, we combined motivation and leadership theories to address these research gaps because a single theory is insufficient and theoretical integrations are necessary to explore the effective management of OCB [85].

First, our findings show that distributive justice is negatively associated with employee OCB. This result is inconsistent with previous research that revealed a positive association between distributive justice and OCB [19,35]. Specifically, equity theory predicts that employees will feel a sense of fairness when they perceive equal input–outcome ratios compared to those of others [30]. Employees with higher levels of distributive justice are likelier to exhibit OCB to improve their organizational sustainability than those with lower levels of distributive justice [19,35]. However, our counterintuitive findings show that this idea of equity theory may not be applicable to public employees. One explanation for this unexpected evidence is based on the motivation crowding-out effect. According to Perry and Hondeghem ([77], p. vii), public employees generally have public service motivation (PSM), defined as “an individual’s orientation to delivering services to people with a purpose to do good for others and society”. PSM is a certain type of intrinsic motivation that can be diminished in a situation where employees transfer the perceived locus of control from inside themselves to the outside, meaning that their PSM is crowded out by the desire for extrinsic compensation [86,87,88]. Perhaps employees feel a strong external locus of control when their organization implements formal compensation practices to increase distributive justice. This means that distributive justice puts excessive pressure on employees with PSM for monetary rewards, which demotivates them to engage in OCB.

Second, our evidence for goal-setting theory is encouraging. Following Jung’s [89] call for research on the effect of goal clarity on employee work-related outcomes, we examined how the clarity of organizational goals relates to employee OCB. Our results indicate that the more specific the goals are, the more OCB occurs, which is consistent with the fundamental idea of goal-setting theory and findings revealed by previous empirical research [10,42,43]. That is, employees are likely to exhibit extra-role behavior for their organizational sustainability when organizational goals are clear rather than ambiguous [10,42]. If employees know what to do better, the likelihood that they will achieve goals increases. This again strengthens employee work motivation by promoting positive work attitudes, including self-efficacy and goal commitment, which results in extra-role behaviors. Therefore, our findings confirm that goal-setting theory offers a useful theoretical rationale for anticipating employee OCB vis-à-vis goal clarity.

Third, we advance the study of organizational behavior and management by combining motivation and leadership theories. Indeed, our study aims to unravel the moderating role of transactional and transformational leadership in the relationships between distributive justice, goal clarity, and employee OCB. Leadership styles have been regarded as organizational factors that shape relationships between work-related outcomes and managerial practices [11,12], revealing how transactional and transformational leadership condition the impact of distributive justice and goal clarity on OCB, which is essential to gain a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of the two leadership styles [12]. We found that transactional leadership alleviates the negative impact of distributive justice on OCB, which is in line with the previous research showing transactional leadership as an important contingent factor in increasing positive work-related outcomes [57,66]. Specifically, transactional leadership effectiveness as a result of contingent reinforcement and management by exception to induce desirable behaviors of subordinates alleviates the negative relationship between distributive justice and OCB. Although public employees are more satisfied with the job itself than with pecuniary rewards, they may still feel a sense of uncertainty about what performance levels they should achieve and how much compensation they receive from the organization. However, transactional leaders mitigate the negative effect of distributive justice on OCB by eliminating uncertainty by communicating with their subordinates about clear job performance methods, responsibilities, and compensation for performance. In other words, distributive justice reduces employee OCB by undermining work motivation. However, if a leader demonstrates transactional leadership in this situation, trust in leadership can be formed based on the economic exchange relationship between the leader and the subordinate, which in turn encourages subordinates with PSM to exhibit OCB.

Finally, the results showed that transformational leadership enhances the positive relationship between goal clarity and OCB, which is consistent with prior research [61,70]. Based on goal-setting theory, clear organizational goals allow employees to feel a sense of goal commitment and increase work motivation. Furthermore, transformational leadership enhances the benefits of goal clarity in promoting OCB. Building on social exchange theory, employees who perceive goal clarity are likely to engage in OCB in an organizational context where leaders show greater transformational leadership that internalizes the norm of reciprocity in employees than those with less transformational leadership [68,69]. Hence, our evidence of the interacting effects of the norm of obligation to reciprocate support from transformational leadership behaviors and the motivation caused by clear, specific organizational goals provides scholars with possibilities and necessities for the combination of motivational and leadership theories.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our study suggests several practical implications. First, given that distributive justice negatively affects OCB, it should be wary of increasing work motivation and encouraging public employees to exhibit OCB by providing economic rewards corresponding to the amount of effort they invest in performing their jobs. That is, excessive emphasis on extrinsic compensation such as wages, performance-based bonuses, and promotions may have a construction effect that weakens employees’ intrinsic motivation in public organizations. Just as many private sector organizations implement personnel compensation management that emphasizes material rewards to strengthen employee work motivation, public organizations also seek to encourage employees to work harder by introducing and expanding a remuneration system centered on monetary reward allocation. However, based on the perspective of the crowding-out effect, these tangible compensation policies could be ineffective in promoting the OCB of public employees who have intrinsic work motivation, such as PSM. Hence, public organizations and managers try to increase employee OCB by redesigning their jobs to be oriented to intrinsic rewards, such as a sense of achievement, responsibility, and meaningful work.

Second, clear organizational goals should be set to encourage employees to exhibit OCB. For instance, it is necessary to specify priorities among various sub-goals to achieve the main goals or to clearly articulate the method and timing of achieving the goals to improve employees’ understanding of organizational goals. In addition, public organizations need to develop quantitative performance measurement indicators so that the degree of goal achievement can be objectively measured in order to increase employee work motivation.

Finally, public managers should exhibit transformational leadership rather than transactional leadership. In this study, we confirmed that even though the fair distribution of organizational outcomes decreases employees’ extra-role behaviors, this negative relationship between distributive justice and OCB weakens when a leader demonstrates transactional leadership behaviors. Consequently, public managers need to communicate with their employees about appropriate rewards corresponding to successful performance and clearly inform them what to do to achieve performance to encourage them to exhibit OCB in situations where they perceive high levels of distributive justice. Furthermore, public managers need to engage in transformational leadership behaviors, including idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, individualized consideration, and inspirational motivation, to increase employee OCB. For example, given that transformational leadership is a managerial capacity that can be developed, public organizations should provide their managers with educational programs and training to cultivate transformational leadership. This is evidently practical, as managers can learn such leadership behaviors while being guided by leadership training programs, such as the FRLM [90,91].

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study makes a significant contribution to public management research by combining motivation and leadership theories, some limitations should be noted. First, the results may not be generalizable to different time periods and to other public organizations in other countries because our study relied on one-year, cross-sectional Korean government data. Therefore, future studies need to collect longitudinal data, including data from various government levels and from many other industries and countries [92,93]. Second, we acknowledge that CMV may still exist because this study relied on a single source of data. Even though Harman’s single-factor test showed no threat of having one major factor dominate covariance (only 39% of the covariance among the measures), the PEVS was anonymous. Moreover, the CFA results indicated that the hypothesized four-factor model fit the data well. However, our study is not sufficient to validate the findings of empirical models. Therefore, future studies should collect data from multiple sources to remove CMV. Third, another topic in the field of public management that future research could explore is the moderating effect of different leadership styles, including servant leadership and ethical leadership. To be specific, servant leadership may condition the influence of goal clarity on OCB because this leadership style could be congruent with goal clarity in that servant leaders go beyond their own self-interest for the sake of the organization and prioritize the fulfillment of their followers’ needs [94]. Ethical leaders focus on transactional efforts to influence their followers to prevent unethical and harmful interpersonal behavior [95]. This feature of ethical leadership matches distributive justice and enhances the positive relationship between distributive justice and OCB. Finally, it should be noted that the measures of transformational and transactional leadership were not created using survey items similar to those in the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire inventory. Therefore, the measures could have weak construct validity. This problem often happens when researchers use secondary data, such as the PEVS, to evaluate employees’ general work attitudes and behaviors and human resource management practices but not specific behavioral dimensions of transactional and transformational leadership. Future research must create better measures.

6. Conclusions

Our study makes several contributions to the motivation and leadership literature. First, by examining the effects of distributive justice and goal clarity on employee OCB, the study answers the question of whether employees’ perceptions of the fairness of outcome allocation and clear understanding of organizational goals play a significant role in encouraging employees to exhibit extra-role behaviors that are beneficial to organizational performance and sustainability. Second, by synthesizing motivation and leadership theories, our study answers the question of whether transactional and transformational leadership strengthens the potential benefits of distributive justice and goal clarity in increasing employee OCB. In doing so, we provide a refined look at the effects of the two managerial practices on OCB for public management scholars and practitioners and meaningful insights into how to manage OCB more effectively by examining the moderating effects of the two leadership styles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.-S.H. and K.-K.M.; data curation: T.-S.H. and K.-K.M.; analysis: T.-S.H. and K.-K.M.; methodology: T.-S.H. and K.-K.M.; writing, reviewing, and editing: T.-S.H. and K.-K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Kyonggi University Research Grant 2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Korea Institute of Public Administration (KIPA), the survey used in this study obtained an IRB review exemption.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study are available at https://www.kipa.re.kr/site/kipa/stadb/selectBaseDBFList.do. Permission to use data must be obtained from KIPA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Recent Trends and Developments. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 80, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The Nature and Dimensionality of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, D.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Bloodgood, J.M. Citizenship Behavior and the Creation of Social Capital in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrenovic, B.; Qin, Y. Understanding the Concept of Individual Level Knowledge Sharing: A Review of Critical Success Factors. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 4, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovic, B.; Obrenovic, S.; Hudaykulov, A. The Value of Knowledge Sharing: Impact of Tacit and Explicit Knowledge Sharing on Team Performance of Scientists. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2015, 1, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Song, H.J. How to Facilitate Innovative Behavior and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Evidence from Public Employees in Korea. Public Pers. Manag. 2021, 50, 509–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althnayan, S.; Alarifi, A.; Bajaba, S.; Alsabban, A. Linking Environmental Transformational Leadership, Environmental Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Organizational Sustainability Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Moorman, R.H. Fairness and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: What Are the Connections? Soc. Justice Res. 1993, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Goal Setting in the Australian Public Service: Effects on Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; McLaughlin, G.B. Leadership and the Organizational Context: Like the Weather? Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.-Y.; Lin, C.-C.; Lu, S.-C.; Chen, H.-L. The Role of Team–Member Exchange in Proactive Personality and Employees’ Proactive Behaviors: The Moderating Effect of Transformational Leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2021, 28, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Feng, N.; Wei, F.; Wang, Y. Rewards and Knowledge Sharing in the CoPS Development Context: The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022; advance online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Cropanzano, R.; Hartnell, C.A. Organizational Justice, Voluntary Learning Behavior, and Job Performance: A Test of the Mediating Effects of Identification and Leader-Member Exchange. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1103–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, D.B.; Cotton-Nessler, N. I Want to Achieve My Goals When I Can? The Interactive Effect of Leader Organization-Based Self-Esteem and Political Skill on Goal-Focused Leadership. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, R.; Kuvaas, B.; Dysvik, A. The role of other orientation in reactions to social and economic leader-member exchange relationships. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 40, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, K.L.; Grijalva, E.; Galvin, B.M.; Owens, B.P.; Joseph, D.L. Motivation to Lead: A Meta-Analysis and Distal-Proximal Model of Motivation and Leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karriker, J.H.; Williams, M.L. Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Mediated Multifoci Model. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H.G. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations, 5th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-7879-8000-9. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Choi, S. Performance Feedback, Goal Clarity, and Public Employees’ Performance in Public Organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.-C.; Lee, J.-W. Realization of a Sustainable High-Performance Organization through Procedural Justice: The Dual Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Organizational Commitment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, R.; Stynen, D.; Van den Broeck, A.; Sels, L.; De Witte, H. How Job Characteristics Relate to Need Satisfaction and Autonomous Motivation: Implications for Work Effort. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, C.C. Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, M.L.; Kulik, C.T. Old Friends, New Faces: Motivation Research in the 1990s. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 231–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Greenberg, J. Organizational Justice: A Fair Assessment of the State of the Literature. In Organizational Behavior: The State of the Science; Greenberg, J., Ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 165–210. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. A Taxonomy of Organizational Justice Theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in Social Exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Alghababsheh, M.; Gallear, D.; Saikouk, T. Justice in Supply Chain Relationships: A Comprehensive Review and Future Research Directions. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2022; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, M.; Rosenberg, S. The Disutility of Equity Theory in Contemporary Management Practice. J. Bus. Econ. Stud. 2011, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marescaux, E.; De Winne, S.; Sels, L. Idiosyncratic Deals from a Distributive Justice Perspective: Examining Co-Workers’ Voice Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.S.; Schaubroeck, J.; Aryee, S. Relationship between Organizational Justice and Employee Work Outcomes: A Cross-National Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoula, O.; Fareed, M.; Ismail, S.A.; Husin, N.S.; Hamid, R.A. A Conceptualization of the Effect of Organisational Justice on Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Organisational Citizenship Behaviour. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2019, 10, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jin, Y.-H. The Effects of Organizational Justice on Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Chinese Context: The Mediating Effects of Social Exchange Relationship. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, J.E. Goal and Process Clarity: Specification of Multiple Constructs of Role Ambiguity and a Structural Equation Model of Their Antecedents and Consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, G.P.; Yukl, G.A. Effects of Assigned and Participative Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1976, 61, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.H.; Rainey, H.G. Goal Ambiguity and Organizational Performance in US Federal Agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoek, M.; Groeneveld, S.; Kuipers, B. Goal Setting in Teams: Goal Clarity and Team Performance in the Public Sector. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2018, 38, 472–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Angert, L. Goal Setting Theory, Job Feedback, and OCB: Lessons from a Longitudinal Study. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Does Public Service Motivation Mediate the Relationship between Goal Clarity and Both Organizational Commitment and Extra-Role Behaviours? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, A.; Giauque, D.; Varone, F.; Anderfuhren-Biget, S. From Leadership to Citizenship Behavior in Public Organizations: When Values Matter. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2014, 34, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.-K. The Effects of Diversity and Transformational Leadership Climate on Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the US Federal Government: An Organizational-Level Longitudinal Study. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2016, 40, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euwema, M.C.; Wendt, H.; Van Emmerik, H. Leadership Styles and Group Organizational Citizenship Behavior across Cultures. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Ahmadi Malek, F.; Yaghoubi Farani, A.; Liobikienė, G. The Role of Transformational Leadership in Developing Innovative Work Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Employees’ Psychological Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G.; Sa, Y. Do Transformational-Oriented Leadership and Transactional-Oriented Leadership Have an Impact on Whistle-Blowing Attitudes? A Longitudinal Examination Conducted in US Federal Agencies. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, T.; Van Wart, M.; Wang, X. Examining the Nature and Significance of Leadership in Government Organizations. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E. A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ayman, R.; Chemers, M.M.; Fiedler, F. The Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness: Its Levels of Analysis. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changar, M.; Atan, T. The Role of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Approaches on Environmental and Ethical Aspects of CSR. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X. Leader–Member Exchange in a Chinese Context: Antecedents, the Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.R.; Glerum, D.R.; Joseph, D.L.; McCord, M.A. A Meta-Analysis of Transactional Leadership and Follower Performance: Double-Edged Effects of LMX and Empowerment. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1255–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, U.T.; Andersen, L.B.; Bro, L.L.; Bøllingtoft, A.; Eriksen, T.L.M.; Holten, A.-L.; Jacobsen, C.B.; Ladenburg, J.; Nielsen, P.A.; Salomonsen, H.H.; et al. Conceptualizing and Measuring Transformational and Transactional Leadership. Adm. Soc. 2016, 51, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.A.; Perin, M.G.; Sampaio, C.H. The Moderating Effect of Managers’ Leadership Behavior on Salespeople’s Self-Efficacy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Managerial Leadership: A Review of Theory and Research. J. Manag. 1989, 15, 251–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.B.; Hughes, L.W.; Norman, S.M.; Luthans, K.W. Using Positivity, Transformational Leadership and Empowerment to Combat Employee Negativity. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Walumbwa, F.O. Family-Friendly Programs, Organizational Commitment, and Work Withdrawal: The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, R.J.; Bunker, B.B. Trust in Relationships: A Model of Development and Decline. In Conflict, Cooperation, and Justice; Rubin, J.Z., Bunker, B.B., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 133–173. ISBN 978-0-7879-0069-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kuvaas, B.; Shore, L.M.; Buch, R.; Dysvik, A. Social and Economic Exchange Relationships and Performance Contingency: Differential Effects of Variable Pay and Base Pay. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 408–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Swaen, V.; Lindgreen, A.; Sen, S. The Roles of Leadership Styles in Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazy, A.; Ganzach, Y. Pay Contingency and the Effects of Perceived Organizational and Supervisor Support on Performance and Commitment. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, O.; Poister, T.H.; Wright, B.E.; Thomas, J.C. Transformational Leadership and Mission Valence of Employees: The Varying Effects by Organizational Level. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2017, 40, 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.E.; Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. Pulling the Levers: Transformational Leadership, Public Service Motivation, and Mission Valence. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchiri, M.K.; Ayoko, O.B. Linking Demographic Diversity to Organisational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.C. An Examination of the Links between Organizational Social Capital and Employee Well-Being: Focusing on the Mediating Role of Quality of Work Life. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2021, 41, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Impact of Organizational Citizenship Behavior on Organizational Performance: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Spector, P.E. The Role of Justice in Organizations: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Moon, K.-K. Transformational Leadership and Employees’ Helping and Innovative Behaviors: Contextual Influences of Organizational Justice. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 1033–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Park, H. Exploring the Relationships among Trust, Employee Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Public Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G.G.; Cummins, W.M. Managing Management Climate; Lexington Books: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Public Management Strategies for Improving Satisfaction with Pandemic-Induced Telework among Public Employees. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 44, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Rich, G.A. Transformational and Transactional Leadership and Salesperson Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Toward a Better Understanding of the Relationship between Transformational Leadership, Public Service Motivation, Mission Valence, and Employee Performance: A Preliminary Study. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Konovsky, M. Cognitive versus Affective Determinants of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 328–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wu, C.; Orwa, B. Contingent Reward Transactional Leadership, Work Attitudes, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Procedural Justice Climate Perceptions and Strength. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohe, C.; Hertel, G. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Test of Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairney, P. Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: How Do We Combine the Insights of Multiple Theories in Public Policy Studies? Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Hondeghem, A. Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-A.; Hsieh, C.-W. Does Pursuing External Incentives Compromise Public Service Motivation? Comparing the Effects of Job Security and High Pay. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1190–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.W. Marketization and Public Service Motivation: Cross-Country Evidence of a Deleterious Effect. Public Pers. Manag. 2022, 52, 00910260221126694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.S. Why Are Goals Important in the Public Sector? Exploring the Benefits of Goal Clarity for Reducing Turnover Intention. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2014, 24, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, P. Developing Transformational Leaders: The Full Range Leadership Model in Action. Ind. Commer. Train. 2006, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailasapathy, P.; Jayakody, J. Does Leadership Matter? Leadership Styles, Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviour and Work Interference with Family Conflict. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 3033–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Lu, K. Does an Imbalance in the Population Gender Ratio Affect FinTech Innovation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 188, 122164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kong, M.; Tong, D.; Zeng, X.; Lai, Y. Property Rights and Adjustment for Sustainable Development during Post-Productivist Transitions in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 122, 106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Dooley, L. How Servant Leadership Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Perceived Procedural Justice and Trust. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Aquino, K.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Kuenzi, M. Who Displays Ethical Leadership, and Why Does It Matter? An Examination of Antecedents and Consequences of Ethical Leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).