Analyzing the Influence of eWOM on Customer Perception of Value and Brand Love in Hospitality Enterprise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Love Theory

2.2. Customer Value and Brand Love

2.3. The Moderator (eWOM)

2.4. Brand Love and Customer Loyalty

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Constructs Measures

3.2. The Study Context and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Measurement Model

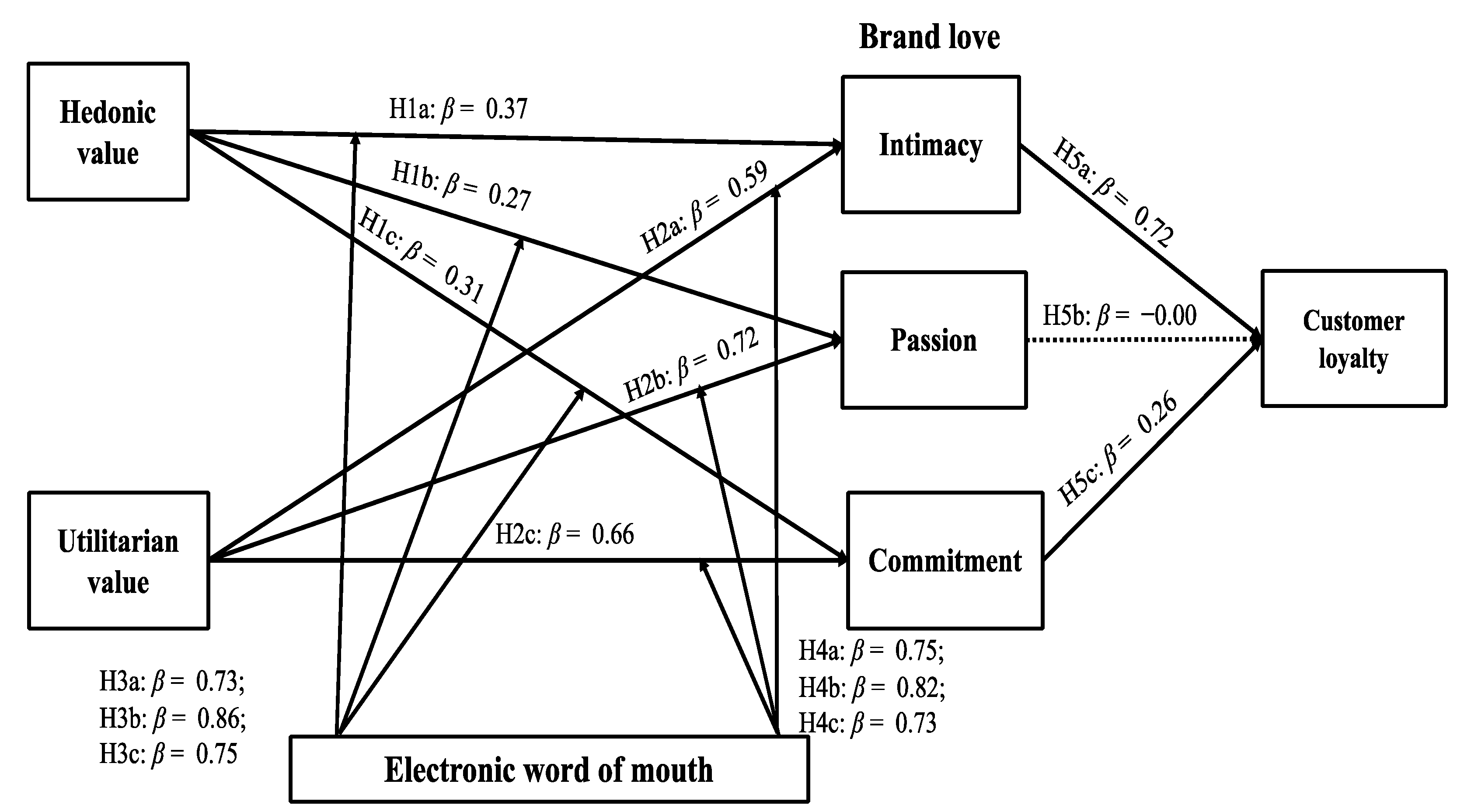

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations and Further Research

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitation and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Helal, M.Y.I. The role of customer orientation in creating customer value in fast-food restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbumathi, R.; Dorai, S.; Palaniappan, U. Evaluating the role of technology and non-technology factors influencing brand love in Online Food Delivery services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.J. I trust friends before I trust companies: The mediation of WOM and brand love on psychological contract fulfilment and repurchase intention. Manag. Matters 2022, 19, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Abbas, J.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Lee, J.; Hwang, J. Differences between robot servers and human servers in brand modernity, brand love and behavioral intentions in the restaurant industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Qu, H.; Yang, J. The formation of sub-brand love and corporate brand love in hotel brand portfolios. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.; Mattila, A.S. The Effect of Self–Brand Connection and Self-Construal on Brand Lovers’ Word of Mouth (WOM). Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Kang, J.; Hyun, S.S.; Fu, X.X. The impact of brand authenticity on building brand love: An investigation of impression in memory and lifestyle-congruence. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Back, K.-J. Effect of cognitive engagement on the development of brand love in a hotel context. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeim, A.R.; Hassan, T.H.; Helal, M.Y.; Saleh, M.I.; Salem, A.E.; Elsayed, M.A.S. Service Value and Repurchase Intention in the Egyptian Fast-Food Restaurants: Toward a New Measurement Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, A.A.; Mohamad Noor, A. SME’s processed frozen food packaging perceived hedonic and utilitarian value influence customers buying decision. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2022, 14, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rathee, S.; Masters, T.M.; Yu-Buck, G.F. So fun! How fun brand names affect forgiveness of hedonic and utilitarian products. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.S.; Huang, S.; Choi, H.-S.C.; Joppe, M. Examining the role of satisfaction and brand love in generating behavioral Intention. In Proceedings of the tTTRA Canada 2016 Conference 2016, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 28–30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-S.; Stepchenkova, S. Examining the impact of experiential value on emotions, self-connective attachment, and brand loyalty in Korean family restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Amp Tour. 2017, 19, 298–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. The Relationships among Perceived Value, Intention to Use Hashtags, eWOM, and Brand Loyalty of Air Travelers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Munnukka, J.; Kiuru, K. Brand love and positive word of mouth: The moderating effects of experience and price. J. Prod. Amp Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairrada, C.M.; Coelho, A.; Lizanets, V. The impact of brand personality on consumer behavior: The role of brand love. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumparthi, V.P.; Patra, S. The Phenomenon of Brand Love: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2019, 19, 93–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.H. The impact of brand love on brand loyalty: The moderating role of self-esteem, and social influences. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2021, 25, 156–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Garg, P. Role of brand experience in shaping brand love. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 45, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. A triangular theory of love. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 93, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ortega, B.; Ferreira, I. How smart experiences build service loyalty: The importance of consumer love for smart voice assistants. Psychol. Amp Mark. 2021, 38, 1122–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yang, Y.-C.; Kuang, T.; Song, H. What Makes a Customer Brand Citizen in Restaurant Industry. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, C.K.; Tse, D.K.; Chan, K.W. Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: Roles of customer–firm affection and customer–staff relationships in services. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Rodrigues, P. Brand love matters to Millennials: The relevance of mystery, sensuality and intimacy to neo-luxury brands. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K. Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands; Powerhouse Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; Chou, S.-F.; Liu, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-Y. Creativity, aesthetics and eco-friendliness: A physical dining environment design synthetic assessment model of innovative restaurants. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D. Managerial practices for designing circular economy business models: The case of an Italian SME in the office supply industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza-Granizo, M.G.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E.; Schlosser, C. Customer value in Quick-Service Restaurants: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, N.J.; Singh, G.; Ali, J.; Lata, R.; Mudaliar, K.; Swamy, Y. Influence of fast-food restaurant service quality and its dimensions on customer perceived value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1324–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.; Weerawardena, J.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. The central role of knowledge integration capability in service innovation-based competitive strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 76, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Verleye, K.; Hatak, I.; Koller, M.; Zauner, A. Three decades of customer value research: Paradigmatic roots and future research avenues. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, M.Y.I. The role of the COVID-19 pandemic in advancing digital transformation infrastructure in Egypt and how it affects value creation for businesses and their customers. Hum. Prog. 2023, 9, 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Daradkeh, F.M.; Hassan, T.H.; Palei, T.; Helal, M.Y.; Mabrouk, S.; Saleh, M.I.; Elshawarbi, N.N. Enhancing Digital Presence for Maximizing Customer Value in Fast-Food Restaurants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-H.; Jeon, H.-M. Exploring the Relationships among Brand Experience, Perceived Product Quality, Hedonic Value, Utilitarian Value, and Brand Loyalty in Unmanned Coffee Shops during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, E.A.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Salem, A.E.; Saleh, M.I.; Helal, M.Y.; Szabo-Alexi, P. Exploration or Exploitation of a Neighborhood Destination: The Role of Social Media Content on the Perceived Value and Trust and Revisit Intention among World Cup Football Fans. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Harnish, R.J. Consumers’ personality and compulsive buying behavior: The role of hedonistic shopping experiences and gender in mediating-moderating relationships. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batat, W. How augmented reality (AR) is transforming the restaurant sector: Investigating the impact of “Le Petit Chef” on customers’ dining experiences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 172, 121013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.G.; Tseng, T.H. On the relationships among brand experience, hedonic emotions, and brand equity. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 994–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.L. Factors affecting intention to revisit an environmental event: The moderating role of enduring involvement. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuvia, A.C.; Batra, R.; Bagozzi, R.P. Love, desire, and identity: A conditional integration theory of the love of things. In Handbook of Brand Relationships; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 364–379. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Villarreal, H.H.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P.; Izquierdo-Yusta, A. Testing Model of Purchase Intention for Fast Food in Mexico: How do Consumers React to Food Values, Positive Anticipated Emotions, Attitude toward the Brand, and Attitude toward Eating Hamburgers? Foods 2019, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduretno, R.B.E.H.P.; Junaedi, M.F.S. Exploring the Effects of Coffee Shop Brand Experience on Loyalty: The Roles of Brand Love and Brand Trust. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2022, 24, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, N.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Rahmani, A.K.; Momayez, A.; Torabi, M.A. Effects of customer forgiveness on brand betrayal and brand hate in restaurant service failures: Does apology letter matter? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 662–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.-Q.; Zhang, S.-N. Understand the differences in the brand equity construction process between local and foreign restaurants. Serv. Bus. 2022, 16, 681–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.H.; Chang, H.H.; Yeh, C.H. The effects of consumption values and relational benefits on smartphone brand switching behavior. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atulkar, S. Brand trust and brand loyalty in mall shoppers. Mark. Intell. Amp Plan. 2020, 38, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Ha, H.-Y. An Empirical Test of Brand Love and Brand Loyalty for Restaurants during the COVID-19 Era: A Moderated Moderation Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosanuy, W.; Siripipatthanakul, S.; Nurittamont, W.; Phayaphrom, B. Effect of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) and perceived value on purchase intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of ready-to-eat food. Int. J. Behav. Anal. 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M. Impact of online WOM on destination trust and intention to travel: A medical tourism perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Amp Manag. 2016, 5, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wola, M.I.; Massie, J.D.D.; Saerang, R.T. The Effect of Experiential Marketing and E-Wom on Customer Loyalty (Case Study: D-Linow Restaurant). J. EMBA J. Ris. Ekon. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2021, 9, 664–679. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, D.-Y. The effect of hedonic and utilitarian values on satisfaction and loyalty of Airbnb users. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1332–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H. Effects of robot restaurants’ food quality, service quality and high-tech atmosphere perception on customers’ behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A. The relationship of service quality dimensions of restaurant enterprises with satisfaction, behavioural intention, eWOM, and the moderating effect of atmosphere. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2020, 16, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruen, T.W.; Osmonbekov, T.; Czaplewski, A.J. eWOM: The impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Conduit, J.; Brodie, R.J. Strategic drivers, anticipated and unanticipated outcomes of customer engagement. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. Identifying associations between mobile social media users’ perceived values, attitude, satisfaction, and eWOM engagement: The moderating role of affective factors. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, S. The influence of electronic word-of-mouth adoption on brand love amongst Generation Z consumers. Acta Commer. 2021, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Sama, R. Title: Determinants of Consumer Loyalty towards Celebrity-Owned Restaurants: The Mediating Role of Brand Love. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyo, J.S.; Mohamad, B.; Adetunji, R.R. An examination of the effects of service quality and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty in the hotel industry. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 8, 653–663. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes Sampaio, C.A.; Hernández Mogollón, J.M.; de Ascensão Gouveia Rodrigues, R.J. The relationship between market orientation, customer loyalty and business performance: A sample from the Western Europe hotel industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 20, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, D. Attracted to or Locked in? Explaining Consumer Loyalty toward Airbnb. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanschitzky, H.; Ramaseshan, B.; Woisetschläger, D.M.; Richelsen, V.; Blut, M.; Backhaus, C. Consequences of customer loyalty to the loyalty program and to the company. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 40, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Peterson, R. Customer Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: The Role of Switching Costs. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Iqbal, Q.; Yang, S. The Impact of Customer Relationship Management and Company Reputation on Customer Loyalty: The Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2020, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Bae, S.Y.; Han, H. Emotional comprehension of a name-brand coffee shop: Focus on lovemarks theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1046–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Jang, S. Relationships among hedonic and utilitarian values, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in the fast-casual restaurant industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Vollhardt, K.; Matthes, I.; Vogel, J. Brand misconduct: Consequences on consumer–brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambauer-Sachse, S.; Mangold, S. Brand equity dilution through negative online word-of-mouth communication. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N. The impact of electronic word of mouth on a tourism destination choice: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Internet Res. 2012, 22, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, V.; Oksanen, A.; Räsänen, P.; Blank, G. Social Media, Web, and Panel Surveys: Using Non-Probability Samples in Social and Policy Research. Policy Amp Internet 2020, 13, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.E. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, M.; Visentin, D.C.; Thapa, D.K.; Hunt, G.E.; Watson, R.; Cleary, M. Chi-square for model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2209–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Canatay, A.; Emegwa, T.; Lybolt, L.M.; Loch, K.D. Reliability assessment in SEM models with composites and factors: A modern perspective. Data Anal. Perspect. J. 2022, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Structural equation modeling. In Models and Methods for Management Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, A.X.; Hackam, D.; Tonelli, M. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: When One Study is Just not Enough. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirilli, E.; Nicolini, P. Digital skills and profile of each generation: A review. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. Rev. Infad De Psicología. 2019, 3, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.A.; Bazeley, P.; Borglin, G.; Craig, P.; Emsley, R.; Frost, J.; Hill, J.; Horwood, J.; Hutchings, H.A.; Jinks, C.; et al. Integrating quantitative and qualitative data and findings when undertaking randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavitt, S.; Barnes, A.J. Culture and the Consumer Journey. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Descriptions | Statistics | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 197 | 51.3 |

| Female | 188 | 48.7 | |

| Age | 18–28 | 135 | 35 |

| 29–39 | 193 | 50 | |

| 40 or more | 57 | 15 | |

| Education | Secondary school or below | 157 | 40.7 |

| University degree | 198 | 51.5 | |

| Postgraduate (Diploma–Master–Ph.D.) | 30 | 7.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 166 | 43.1 |

| Married | 164 | 42.6 | |

| Married with children | 55 | 14.3 |

| Describe Your Last Experience with a Fast-Food Restaurant Brand. | Item-to-Factor Loadings | AVE | CR | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic value | 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.94 | |

| I ate out at this fast-food restaurant brand and felt good about it. | 0.85 | |||

| Eating out at this fast-food restaurant brand was fun and pleasant. | 0.85 | |||

| The dining experience at this fast-food restaurant brand was a joy. | 0.86 | |||

| The dining experience at this fast-food restaurant brand improved my mood. | 0.86 | |||

| During the dining experience at this fast-food restaurant, I felt the excitement of searching for food. | 0.88 | |||

| Utilitarian value | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.93 | |

| Eating out at this fast-food restaurant brand was convenient. | 0.86 | |||

| Eating out at this fast-food restaurant brand was pragmatic and economical. | 0.88 | |||

| Eating out at this fast-food restaurant brand was not a waste of money. | 0.86 | |||

| Service at this fast-food restaurant brand was quick. | 0.84 | |||

| Brand love intimacy | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| I feel emotionally close to this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.86 | |||

| I have a cozy relationship with this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.86 | |||

| I understand this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.87 | |||

| There is a certain intimacy between this fast-food restaurant brand and me. | 0.88 | |||

| Brand love passion | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.94 | |

| I cannot imagine another fast-food restaurant brand making me as happy as this brand. | 0.89 | |||

| I adore this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.88 | |||

| This fast-food restaurant brand makes me feel great delight. | 0.90 | |||

| Just seeing this fast-food restaurant brand is exciting for me. | 0.85 | |||

| Brand love commitment | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.91 | |

| I am committed to maintaining my relationship with this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.86 | |||

| I plan to continue my relationship with this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.87 | |||

| My relationship with this fast-food restaurant brand is a good decision. | 0.88 | |||

| I have confidence in the stability of my relationship with this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.86 | |||

| Electronic word of mouth | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.95 | |

| I often read other customers’ online reviews to know what this fast-food restaurant brand makes good impressions on others. | 0.926 | |||

| I often read other customers’ online reviews to ensure I choose the right fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.82 | |||

| I often consult other customers’ online reviews to help them choose an attractive fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.93 | |||

| I frequently gather information from customers’ online reviews before choosing a specific fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.94 | |||

| I worry about my decision if I do not read customers’ online reviews when I go to a fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.92 | |||

| When I go to a fast-food restaurant, customers’ online reviews make me confident in purchasing from this brand. | 0.97 | |||

| Customer loyalty | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.93 | |

| I want to choose this fast-food restaurant brand again in the month. | 0.86 | |||

| I am willing to eat from this fast-food restaurant brand in the future. | 0.88 | |||

| I will encourage others to purchase from this fast-food restaurant brand. | 0.90 | |||

| I would say positive things about this fast-food restaurant brand to others. | 0.83 |

| Constructs | Hedonic Value | Utilitarian Value | Brand Love Intimacy | Brand Love Passion | Brand Love Commitment | Electronic Word of Mouth | Customer Loyalty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic value | 0.86 | ||||||

| Utilitarian value | 0.66 | 0.86 | |||||

| Brand love intimacy | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.86 | ||||

| Brand love passion | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.87 | |||

| Brand love commitment | 0.45 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.86 | ||

| Electronic word of mouth | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.91 | |

| Customer loyalty | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.86 |

| Hypotheses | Direct and Interaction Effects | Beta (ß) | t-Values | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Hedonic value à Intimacy | 0.37 | 4.63 | 0.000 *** |

| H1b | Hedonic value à Passion | 0.27 | 2.89 | 0.004 ** |

| H1c | Hedonic value à Commitment | 0.31 | 3.07 | 0.002 ** |

| H2a | Utilitarian value à Intimacy | 0.59 | 6.97 | 0.000 *** |

| H2b | Utilitarian value à Passion | 0.72 | 7.30 | 0.000 *** |

| H2c | Utilitarian value à Commitment | 0.66 | 6.24 | 0.000 *** |

| H3a | Hedonic value × EWOM à Intimacy | 0.73 | 13.32 | 0.000 *** |

| H3b | Hedonic value × EWOM à Passion | 0.86 | 15.64 | 0.000 *** |

| H3c | Hedonic value × EWOM à Commitment | 0.75 | 11.92 | 0.000 *** |

| H4a | Utilitarian value × EWOM à Intimacy | 0.75 | 12.06 | 0.000 *** |

| H4b | Utilitarian value × EWOM à Passion | 0.82 | 13.58 | 0.000 *** |

| H4c | Utilitarian value × EWOM à Commitment | 0.73 | 10.44 | 0.000 *** |

| H5a | Intimacy à Customer loyalty | 0.72 | 4.63 | 0.000 *** |

| H5b | Passion à Customer loyalty | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.974 |

| H5c | Commitment à Customer loyalty | 0.26 | 2.67 | 0.008 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshreef, M.A.; Hassan, T.H.; Helal, M.Y.; Saleh, M.I.; Tatiana, P.; Alrefae, W.M.; Elshawarbi, N.N.; Al-Saify, H.N.; Salem, A.E.; Elsayed, M.A.S. Analyzing the Influence of eWOM on Customer Perception of Value and Brand Love in Hospitality Enterprise. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097286

Alshreef MA, Hassan TH, Helal MY, Saleh MI, Tatiana P, Alrefae WM, Elshawarbi NN, Al-Saify HN, Salem AE, Elsayed MAS. Analyzing the Influence of eWOM on Customer Perception of Value and Brand Love in Hospitality Enterprise. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097286

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshreef, Mohamed A., Thowayeb H. Hassan, Mohamed Y. Helal, Mahmoud I. Saleh, Palei Tatiana, Wael M. Alrefae, Nabila N. Elshawarbi, Hassan N. Al-Saify, Amany E. Salem, and Mohamed A. S. Elsayed. 2023. "Analyzing the Influence of eWOM on Customer Perception of Value and Brand Love in Hospitality Enterprise" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097286

APA StyleAlshreef, M. A., Hassan, T. H., Helal, M. Y., Saleh, M. I., Tatiana, P., Alrefae, W. M., Elshawarbi, N. N., Al-Saify, H. N., Salem, A. E., & Elsayed, M. A. S. (2023). Analyzing the Influence of eWOM on Customer Perception of Value and Brand Love in Hospitality Enterprise. Sustainability, 15(9), 7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097286