Determining Service Quality Indicators to Recruit and Retain International Students in Malaysia Higher Education Institutions: Global Issues and Local Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

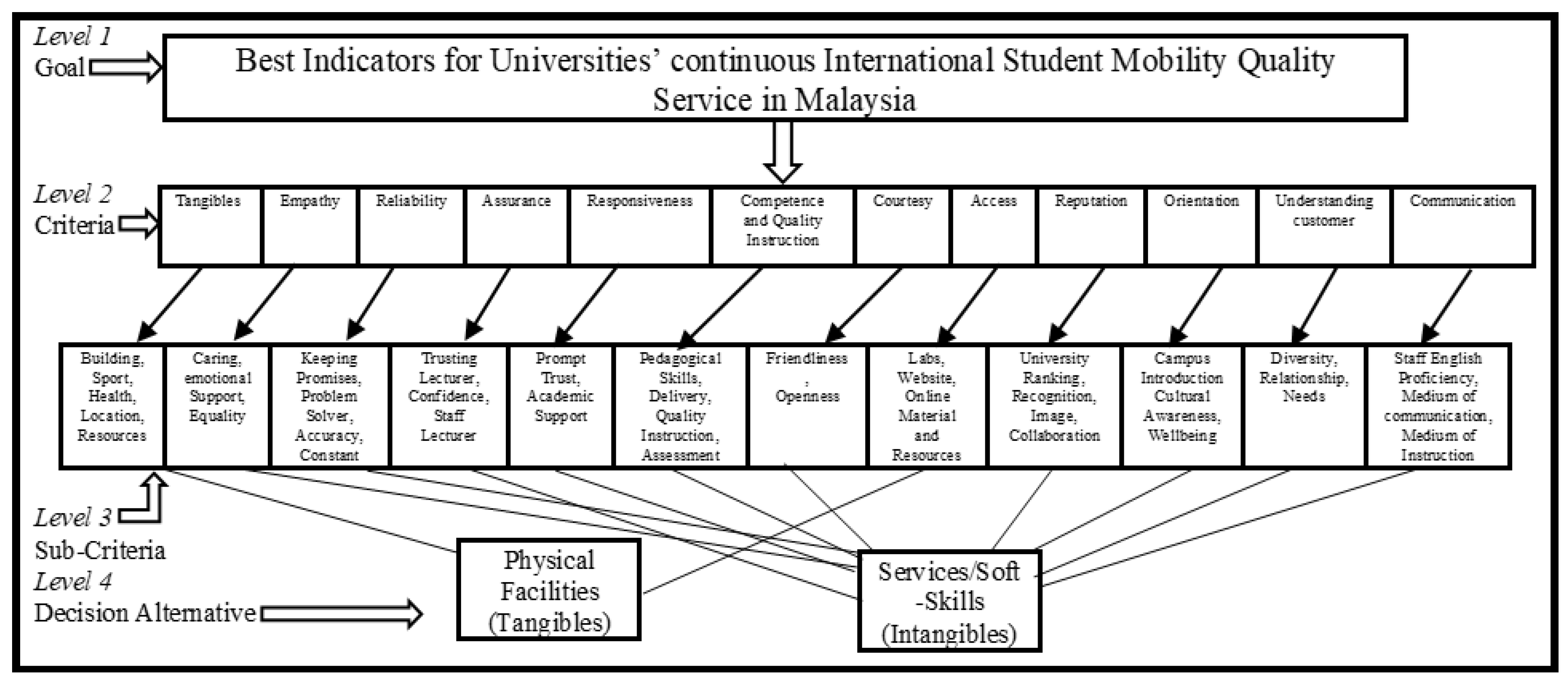

2.1. Theoretical Framework

- Tangibles: The appearance of facilities, physical equipment, location, and the mien of the institution’s personnel;

- Empathy: Caring and individualised attention that the firm provides to its customers;

- Reliability: The ability to perform the promised or advertised service accurately and reliably;

- Assurance (including communication, competence, credibility, courtesy, and security): employees’ knowledge, politeness, and ability to inspire confidence and trust;

- Responsiveness: The willingness to help customers and provide prompt service.

- Courtesy is about the friendliness of local/international lecturers with international students and their willingness to provide support;

- Access emphasises university management’s availability to address international student issues and the accessibility of the academic facilities;

- Competence and Quality Instruction emphasises a lecturer’s pedagogical skills, teaching skills, and mood of lecture delivery. It also talks about lecturer creativity in teaching and classroom management. Quality instruction emphasises local/international lecturers’ classroom preparedness, subject matter, learning engagement, and assessment;

- Reputation deals with the university’s reputation, ranking, world recognition, image, and collaboration;

- Orientation talks about how the university introduces the campus to international students, academic programmes, cultural awareness, and well-being, and follows up on international students’ progress;

- Communication is a medium of language used by administrators and university activities or programmes. It talks about their ability to communicate in English and the availability of English programmes for international students;

- Understanding the Customer relates to how university management handles diversity, cultural awareness, relationships with international students, and academic support.

2.2. Quality Management, Service in Higher Institution, International Student Satisfaction: A Global Perspective

2.3. Internationalisation of Higher Education and Student Mobility: A Global Context

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Setting

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. AHP Process

4. Findings

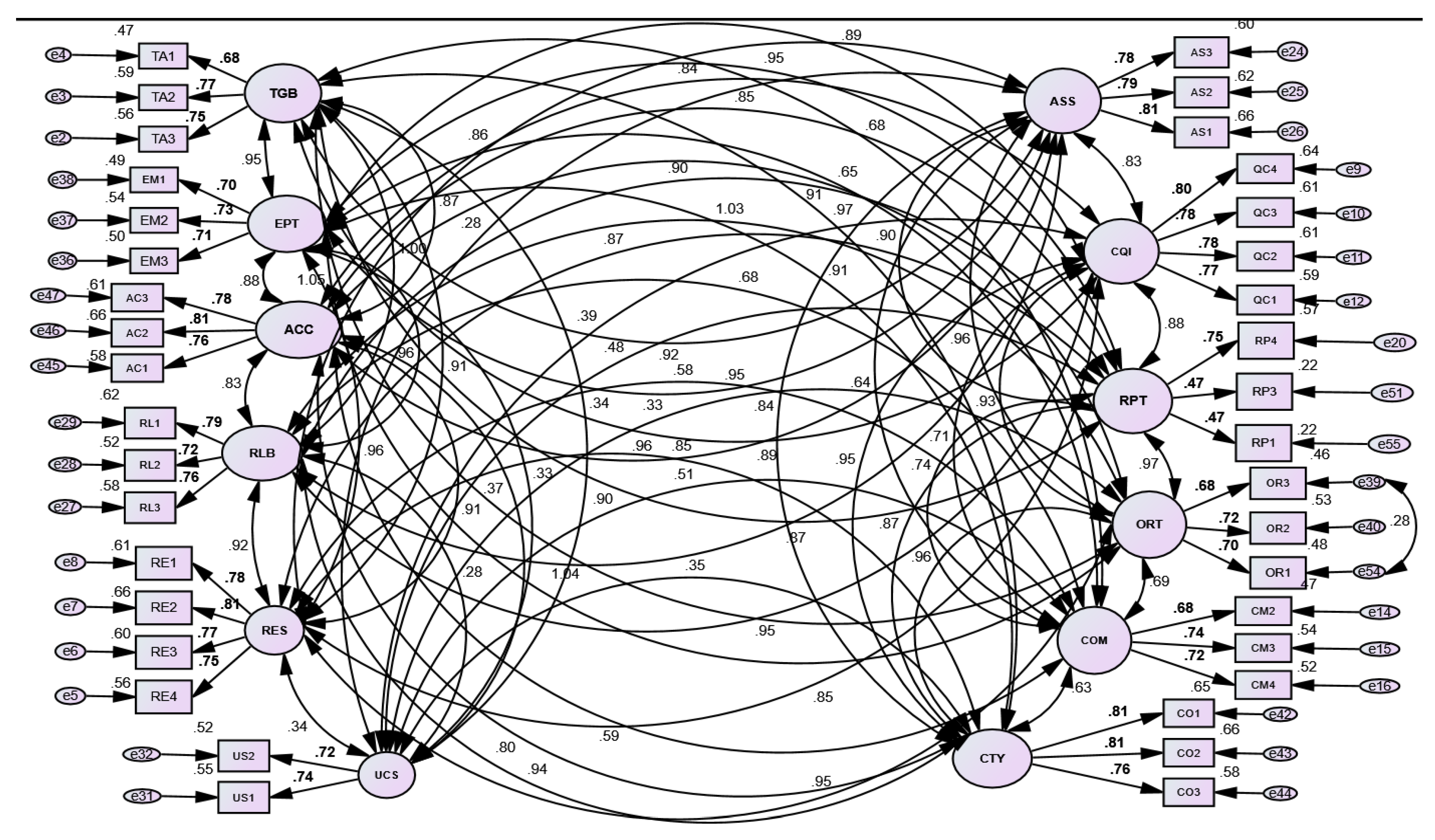

4.1. Measurement Model

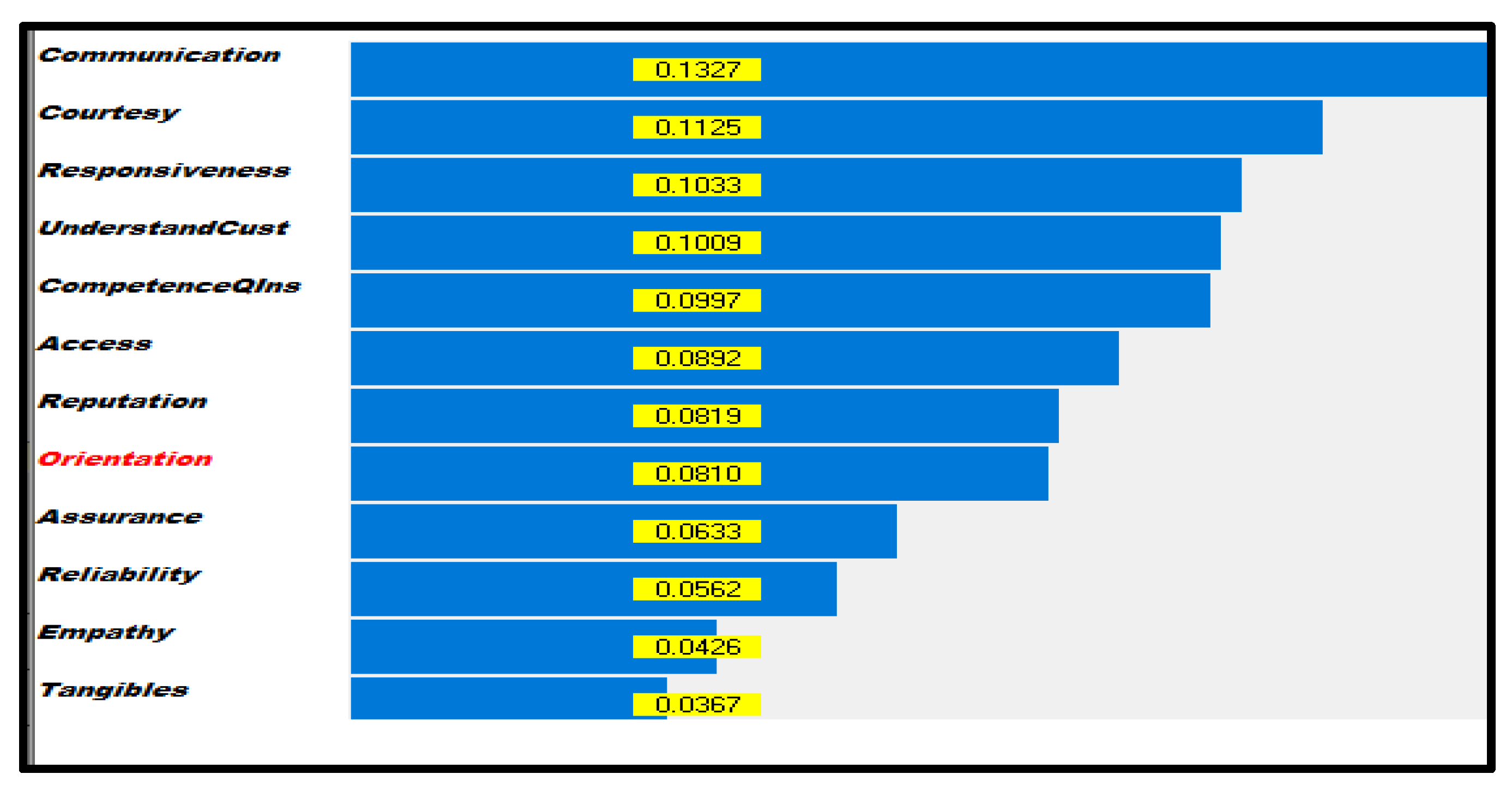

4.2. AHP Results

4.3. Overall Weights and Ranking

4.4. Pareto Principle

5. Discussion

6. Practical Implications, Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Research Instrument

| No | Statement | Good | Needs Modification | Delete |

| 1. Tangibles | ||||

| 1 | Modern facilities are provided at my university. | |||

| 2 | My university possesses a suitable location. | |||

| 3 | The facilities at my university accommodate the international student population. | |||

| 4 | My university provides educational resources related to the educational process efficiently. | |||

| 5 | My university environment is visually pleasing | |||

| 6 | Signs around the university campus are written in both BM and English. | |||

| 7 | The information in the signs is helpful. | |||

| 2. Empathy | ||||

| 8 | International students are notified in a timely way of important dates (schedules, examinations and events). | |||

| 9 | My university puts international students’ academic development as one of its top priorities. | |||

| 10 | University staff pays attention to international students’ academic progress on campus. | |||

| 11 | Classes hours or periods are convenient for international students. | |||

| 12 | In my university, I feel that local and international students are treated equally. | |||

| 13 | When I have a problem related to my academic issues, a university member will help me solve it. | |||

| 3. Reliability | ||||

| 14 | My university implements a consistent academic fee structure. | |||

| 15 | My university performs the service right service the first time. | |||

| 16 | My university provides service at the time they promise to do so. | |||

| 17 | My university practices good records management | |||

| 18 | Administrative staff are willing to promote international students’ activities | |||

| 19 | My university provides academic consultation services for students who need them | |||

| 20 | My university assigns a supervisor who can help me to achieve academically | |||

| 4. Assurance | ||||

| 20 | My lecturers encourage students to do well in their studies. | |||

| 21 | As an international student, I feel respected. | |||

| 22 | I find the academic staff courteous to international students. | |||

| 23 | I find my lecturers able to answer my academic questions. | |||

| 24 | My lecturers make me feel confident in my ability to complete my coursework | |||

| 25 | The criteria of the answer scheme are clearly explained by my lecturers | |||

| 5. Responsiveness | ||||

| 26 | My university’s international affairs act immediately on our complaints | |||

| 27 | My university administrative staff were efficient in dealing with my requests | |||

| 28 | When I have a problem with the university services, the university employees tell me when it will be solved. | |||

| 29 | I receive prompt responses when I call the university offices. | |||

| 30 | My university students’ affairs office is sensitive to my needs | |||

| 31 | My university’s academic programmes are applicable across cultures | |||

| 6. Competence & Quality Instruction | ||||

| 32 | My lecturers are competent in the subjects they are teaching. | |||

| 33 | My lecturers are skilful in delivering course materials | |||

| 35 | My lecturers display content mastery of the subjects they are teaching | |||

| 37 | My lecturers seemed to be qualified to teach their courses/subjects | |||

| 38 | My lecturers design learning tasks (e.g., assignments or projects) where students can bring out their best | |||

| 39 | My lecturers sustain students’ level of interest throughout all the class time | |||

| My lecturers hold class regularly in a timely manner | ||||

| 7. Courtesy | ||||

| 40 | Academic staff are friendly to international students | |||

| 41 | Non-academic staff are friendly when dealing with international students | |||

| 42 | Academic staff are helpful when international students have issues related to academics. | |||

| 43 | Non-academic staff are helpful when international students have issues related to academics. | |||

| 44 | My university is open to suggestions from international students | |||

| 45 | I have been invited by local students to participate in social activities | |||

| 8. Access | ||||

| 57 | I find my university management accessible when I have a question or need information | |||

| 58 | I find my university website a useful source of information | |||

| 59 | I can easily access online course-related materials | |||

| 60 | I find the university library to be a good resource for my academic work. | |||

| 63 | My lecturers effectively use online resources to meet course requirements. | |||

| 64 | I get information from billboards or posters around the campus | |||

| 65 | A university directory is made available for general students’ use | |||

| 9. Reputation | ||||

| 76 | My university is well-recognised worldwide | |||

| 77 | My university is ranked among the top university in the world | |||

| 78 | My university is recognised as a quality education provider in my home country | |||

| 79 | My university has a good academic reputation in my home country | |||

| 80 | My university has a strong image in my home country regarding graduate placement. | |||

| 81 | My university is known for international collaboration | |||

| 10. Orientation | ||||

| 82 | My university gives orientation programmes to international students on academic policies/procedures. | |||

| 83 | My university gives orientation to international students on academic programs available. | |||

| 84 | My university provides an orientation to international students about cultural awareness. | |||

| 85 | My university gives an orientation to international students on how to find a good accommodation | |||

| 86 | My university gives orientation about basic necessities for survival | |||

| 87 | My university provides follow-up orientation activities (academic & non-academic) | |||

| 11. Understanding the Customer | ||||

| 88 | The management staff members of my university have adequate exposure to handling students of diverse backgrounds. | |||

| 89 | My university management conducts meetings with international students to understand their needs. | |||

| 90 | The academic services extended by my university meet my expectations | |||

| 91 | Non-academic services extended by my university meet my expectations | |||

| 92 | I would recommend my university to other international students | |||

| 93 | I’m happy to be an international student at my university | |||

| 12. Communication | ||||

| 107 | My university administrative staff communicates with me in English | |||

| 108 | When it comes to group activities among local and international students, the English language is used as a medium of communication | |||

| 109 | My lecturers use English as a medium of instruction | |||

| 110 | I find it easy to communicate in English during a transaction with school mates. | |||

| 111 | I understand the communication that I get from the university | |||

| 112 | I am well-informed about my university activities | |||

| 113 | My university provides services for international students to improve their communication skills | |||

| Criteria A | More Important than | Equally Important | More Important than | Criteria B | ||||||

| 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) |

| Tangibles (Physical facilities) | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Tangibles | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programmes for international students) | |||||||||

| 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Empathy | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programmes for international students) | |||||||||

| 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 10.Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Reliability | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Assurance | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Responsiveness | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 9. Reputation University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Competence & Quality Insurance | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Courtesy | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Access | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Access | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Access | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Access | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Access | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Access | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Access | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Access | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Access | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Access | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Reputation | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 10. Orientation(Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

| Orientation | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance (Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Understanding the Customer | 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | |||||||||

| 12. Communication (Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and availability of English programme for international students) | 1. Tangibles (Physical facilities) | |||||||||

| Communication | 2. Empathy (Caring towards international students) | |||||||||

| Communication | 3. Reliability (Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems) | |||||||||

| Communication | 4. Assurance (Staffs’ knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to International students) | |||||||||

| Communication | 5. Responsiveness (Universities’ willingness to help International students and provide prompt service) | |||||||||

| Communication | 6. Competence & Quality Insurance Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, mood of delivery, classroom preparedness & assessment) | |||||||||

| Communication | 7. Courtesy (Lecturers’ relationship with foreign students, academic support in studies/research & foreign students with the local community in Malaysia) | |||||||||

| Communication | 8. Access (University management availability to foreign student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities) | |||||||||

| Communication | 9. Reputation (University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration) | |||||||||

| Communication | 10. Orientation (Campus introduction to international students, academic programme, cultural awareness and bond) | |||||||||

| Communication | 11. Understanding the Customer (University management handling diversity, culture awareness, inclusiveness & support) | |||||||||

References

- Munusamy, M.M.; Hashim, A. Internationalisation of higher education in Malaysia: Insights from higher education administrators. AEI Insights Int. J. Asia-Eur. Relat. 2019, 51, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L. Analytic Quality Glossary, Quality Research International. 2022. Available online: https://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/glossary/internationalisation.htm (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE). Internationalization Policy; Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE): Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2011.

- Ministry of Education (MOE). Malaysia. Executive Summary Malaysia Education Blueprint 2015–2025 (Higher Education). 2022. Available online: https://www.um.edu.my/docs/um-magazine/4-executive-summary-pppm-2015-2025.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Sanders, J.S. National internationalisation of higher education policy in Singapore and Japan: Context and competition. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2019, 49, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.; Wang, L.W.; Hassan, A. Expectations and perceptions of overseas students towards service quality of higher education institutions in Scotland. Int. Bus. Res. 2013, 6, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matijašević-Obradović, J.; Subotin, M. Importance of reforms and internationalisation of Higher education in accordance with the Bologna Process. Pravo-Teor. I Praksa 2019, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleu, F.G.; Gutierrez, E.M.A.G.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Garza Villegas, J.B.; Vazquez Hernandez, J. Increasing service quality at a university: A continuous improvement project. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2021, 29, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnerud, D. 25 years of quality management research—Outlines and trends. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 208–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdous, S.S.; Farooqi, R. Service Quality To E-Service Quality: A Paradigm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Bangkok, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–7 March 2019; Available online: www.ieomsociety.org/ieom2019/papers/404.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Jackson, M.; Ray, S.; Bybell, D. International students in the US: Social and psychological adjustment. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 3, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.; Berry, L. Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J. Retail. 1991, 67, 420–450. [Google Scholar]

- Najimdeen, A.H.A.; Amzat, I.H.; Ali, H.B.M. The impact of service quality dimensions on students’ satisfaction: A study of international students in Malaysian public universities. IIUM J. Educ. Stud. 2021, 9, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerguis, A. The Gaps Model of Service Quality and Customer Relationships in A Digital Marketing Context. University Salford Manchester. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335172190_The_Gaps_Model_of_Service_Quality_and_Customer_Relationships_in_A_Digital_Marketing_Context (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Agarwal, A.; Kumar, G. Identify the need for developing a new service quality model in today’s scenario: A review of service quality models. Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, H.; Deca, L. Internationalisation of higher education, challenges and opportunities for the next decade. In European Higher Education Area: Challenges for A New Decade; Curaj, A., Deca, L., Pricopie, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri, R.; Krush, M.T. Salesperson empathy, ethical behaviors, and sales performance: The moderating role of trust in one’s manager. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2015, 35, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, W.; Saira, A.; Zulfiqar, S. Effect of employee empathy on customer satisfaction and loyalty during employee-customer interactions: The mediating role of customer affective commitment and perceived service quality. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Chau, K.Y.; Zheng, J.; Hanjani, A.N.; Hoang, M. The mediating role of international student satisfaction in the influence of higher education service quality on institutional reputation in Taiwan. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1847979020971955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaffa, W.S.W.; Rahman, R.A.; Ab Wahid, H. Evaluating service quality at Malaysian public universities: Perspective of international students by world geographical regions. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 856–867. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh, I. Turning the world towards Malaysian education. In New Straight Time. 2017. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2017/05/237032/turning-world-towards-malaysian-education (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Chandra, T.; Hafni, L.; Chandra, S.; Purwati, A.A.; Chandra, J. The influence of service quality, university image on student satisfaction and student loyalty. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacoup, P.; Michel, C.; Habchi, G.; Pralus, M. From a quality management system (QMS) to a lean quality management system (LQMS). TQM J. 2018, 30, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, Y.; Purwanto, A.; Azizah, F.N.; Wijoyo, H. Impact of service quality, university image and students satisfaction towards student loyalty: Evidence from Indonesian private universities. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 3916–3924. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3873702 (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Chen, R.; Lee, Y.D.; Wang, C.H. Total quality management and sustainable competitive advantage: Serial mediation of transformational leadership and executive ability. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 31, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darawong, C.; Sandmaung, M. Service quality enhancing student satisfaction in international programs of higher education institutions: A local student perspective. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2019, 29, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Business Guide Indonesia. Indonesia’s Higher Education Sector: Aiming to Become A Top Destination in Southeast Asia, 2019. GBGI. Available online: http://www.gbgindonesia.com/en/education/article/2019/indonesia_s_higher_education_sector_aiming_to_become_a_top_destination_in_southeast_asia_11892.php (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Maletič, D.; Lasrado, F.; Maletič, M.; Gomišček, B. Analytic hierarchy process application in different organisational settings. In Applications and Theory of Analytic Hierarchy Process—Decision Making for Strategic Decisions; De Felice, F., Saaty, T.L., Petrillo, A., Eds.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/51754 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Suciptawati, N.L.P.; Paramita, N.L.P.S.P.; Aristayasa, I.P. Customer satisfaction analysis based on service quality: Case of local credit provider in Bali. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1321, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Khawaja, N.G. A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011, 35, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of International Education. Number of International Students in the United States Hits All-Time High, 2019. The Power of International Education. Available online: https://www.iie.org/Why-IIE/Announcements/2019/11/Number-of-International-Students-in-the-United-States-Hits-All-Time-High (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Jiang, Q.; Yuen, M.; Horta, H. Factors influencing life satisfaction of international students in mainland China. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2020, 44, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasli, A.M.; Bhatti, M.A.; Norhalim, N.; Kowang, T.O. Service quality in higher education: Study of Turkish students in Malaysian universities. J. Manag. Info 2014, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, M.S.A.; Newaz, F.T.; Ramasamy, R. Students’ perception of lecturers’ competency and the effect on institution loyalty: The mediating role of students’ satisfaction. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2020, 16, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y. Internationalisation of higher education: New players in a changing scene. Educ. Res. Eval. 2022, 27, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelena, M.O.; Maja, S. Importance of Reforms and Internationalization of Higher Education in Accordance with The Bologna Process. Pravo-Teor. I Praksa 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, H.; Altbach, P. 70 Years of internationalisation in tertiary education: Changes, challenges and perspectives. In The Promise of Higher Education; van’t Land, H., Corcoran, A., Iancu, D.D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higher Education Statistics Agency. HE Student Enrolments by Domicile and Region of HE Provider: Academic Years 2014/15 to 2017/18, 2019. Higher Education. 2019. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/where-study (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Ongo, M.O. Examining Perceptions of Service Quality of Student Services and Satisfaction among International Students at Universities in Indiana and Michigan. Ph.D. Thesis, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J. From intangibility to tangibility on service quality perceptions: A comparison study between consumers and service providers in four service industries. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2002, 12, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Grebennikova, V.; Razinkina, E.; Rudenko, E. Relationship between globalisation and internationalisation of higher education. In Proceedings of the VI International Scientific Conference “Territorial Inequality: A problem or development driver, (REC-2021), Ekaterinburg, Russia, 23–25 June 2021; Volume 301, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F.S.; Yip, N. Comparing service quality in public vs private distance education institutions: Evidence based on Malaysia. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2019, 20, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Public/private in higher education: A synthesis of economic and political approaches. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asia-Pacific Association for International Education (APAIE). Recent Development of International Higher Education in Malaysia: Regional Reports, 2018. APAIE. Available online: https://www.iie.org/Why-IIE/Events/2018/03/2018-APAIE-Conference (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Kar, B. Service Quality and SERVQUAL Model: A Reappraisal. Amity J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 1, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Ameyaw, E.E.; Owusu, E.K.; Pärn, E.; Edwards, D.J. Review of application of analytic hierarchy process (AHP) in construction. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018, 19, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, L.; Puls-Elvidge, S.; Welzant, H.; Crawford, L. Definitions of 1uality in higher education: A synthesis of the literature. High Learn. Res. Commun. 2015, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.V.; Nguyen, T.N.Q.; Tran, N.T.; Paramita, W. It takes two to tango: The role of customer empathy and resources to improve the efficacy of frontline employee empathy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a glance 2021: OECD indicators, 2021. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=41771&filter=all (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Khoo, S.; Ha, H.; McGregor, S.L.T. Service quality and student/customer satisfaction in the private tertiary education sector in Singapore. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M. A Comparative Study of the Internationalisation of Higher Education Policy in Australia and China (2008–2015). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, S.; He, L. Student mobility in transnational higher education: Study abroad at international branch campuses. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2020, 26, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, H.; Bakhtavar, E.; Chhipi-Shrestha, G.; Mian, H.R.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Decision making for risk management: A multi-criteria perspective. In Methods in Chemical Process Safety; Khan, F.I., Amyotte, P.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaei, D.; Erkoyuncu, J.; Roy, R. A review of multi-criteria decision making methods for enhanced maintenance delivery. Procedia CIRP 2015, 37, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.A.; Abdul Razak, N.; Qasem, Y.A.M.; Saeed Mohammed, M.A. Intercultural learning challenges affecting international students’ sustainable learning in Malaysian higher education institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yijing, L.; Lim, E.T.K.; Yong, L.; Chee-Wee, T. Tangiblizing your service: The role of visual cues in service e-tailing. In Proceedings of the Thirty-ninth International Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Suwarni, S.; Moerdiono, A.; Prihatining, I.; Sangadji, E.M. The effect of lecturers’ competency on students’ satisfaction through perceived teaching quality. KnE Soc. Sci. 2020, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Frequency | Percent | Country | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 26 | 1.7 | Mauritania | 1 | 0.1 |

| Algeria | 42 | 2.7 | Mauritius | 1 | 0.1 |

| Australia | 4 | 0.3 | Morocco | 7 | 0.4 |

| Bangladesh | 27 | 2.2 | Myanmar | 4 | 0.3 |

| Benin | 1 | 0.1 | New Zealand | 1 | 0.1 |

| Brunei | 3 | 0.2 | Niger | 1 | 0.1 |

| Cameroon | 1 | 0.1 | Nigeria | 109 | 6.9 |

| Canada | 4 | 0.3 | Oman | 17 | 1.1 |

| Central Africa | 4 | 0.3 | Pakistan | 57 | 3.1 |

| Chad | 4 | 0.3 | Palestine | 25 | 1.6 |

| China | 149 | 9.3 | Philippines | 9 | 0.6 |

| Comoros | 8 | 0.5 | Puerto Rico | 1 | 0.1 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 1 | 0.1 | Qatar | 6 | 0.4 |

| Djibouti | 2 | 0.1 | Russia | 1 | 0.1 |

| Egypt | 16 | 1.0 | Saudi Arabia | 17 | 1.1 |

| Eritrea | 4 | 0.3 | Senegal | 6 | 0.4 |

| Ethiopia | 3 | 0.2 | Sierra Leone | 2 | 0.1 |

| Gambia | 12 | 0.8 | Singapore | 17 | 1.1 |

| Germany | 1 | 0.1 | Somalia | 54 | 3.4 |

| Ghana | 6 | 0.4 | South Africa | 1 | 0.1 |

| Guinea | 17 | 1.1 | Sri Lanka | 10 | 0.6 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | 0.1 | Sudan | 31 | 2.0 |

| India | 55 | 3.5 | Sweden | 1 | 0.1 |

| Indonesia | 144 | 9.1 | Syria | 14 | 0.9 |

| Iran | 34 | 2.2 | Taiwan | 4 | 0.3 |

| Iraq | 49 | 3.1 | Tanzania | 8 | 0.5 |

| Italy | 3 | 0.2 | Thailand | 26 | 1.7 |

| Japan | 6 | 0.4 | Tunisia | 9 | 0.6 |

| Jordan | 57 | 3.6 | Turkmenistan | 1 | 0.1 |

| Kazakhstan | 2 | 0.1 | Turkey | 14 | 0.9 |

| Kenya | 7 | 0.4 | UAE | 4 | 0.3 |

| Korea_Japan | 1 | 0.1 | Uganda | 6 | 0.4 |

| Kuwait | 1 | 0.1 | UK | 2 | 0.1 |

| Laos | 1 | 0.1 | USA | 3 | 0.2 |

| Libya | 19 | 1.2 | Uzbekistan | 4 | 0.3 |

| Lithuania | 5 | 0.3 | Vietnam | 3 | 0.2 |

| Maldives | 10 | 0.6 | Yemen | 67 | 4.3 |

| Mali | 2 | 0.1 | Zimbabwe | 1 | 0.1 |

| Total | 1273 | 100.0 | |||

| Tangible | Empathy | Reliability | Assurance | Responsiveness | Competency and Quality Insurance | Courtesy | Access | Reputation | Orientation | Understanding Customer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible | 1 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.41 |

| Empathy | 2.11 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.50 |

| Reliability | 1.48 | 2.47 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| Assurance | 2.92 | 3.04 | 1.83 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.59 |

| Responsiveness | 4.39 | 2.63 | 2.74 | 4.25 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.75 |

| Competency and Quality Insurance | 2.86 | 2.49 | 1.79 | 2.99 | 2.09 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 1.28 |

| Courtesy | 2.84 | 2.82 | 1.54 | 1.97 | 2.49 | 1.34 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.71 |

| Access | 2.32 | 2.83 | 1.36 | 1.89 | 1.47 | 1.29 | 2.36 | 1 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.56 |

| Reputation | 1.66 | 1.89 | 1.44 | 1.23 | 1.28 | 1.16 | 1.28 | 1.40 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| Orientation | 2.21 | 1.31 | 1.62 | 1.53 | 1.06 | 1.21 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.45 |

| Understanding Customer | 2.46 | 2.00 | 1.61 | 1.68 | 1.34 | 0.78 | 1.40 | 1.79 | 1.99 | 2.23 | 1 |

| Communication | 2.52 | 1.85 | 2.42 | 1.90 | 1.60 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.65 | 1.97 | 2.38 | 1.83 |

| Model Fit | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Fit Measures | ||||||||

| X2 | DF | X2/DF | RMR | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | p | |

| Criteria | <0.05 | <0.05 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ||||

| Obtained | 2220.222 | 562 | 3.334 | 0.037 | 0.043 | 0.918 | 0.900 | 0.001 |

| Incremental Fit Measures | Parsimony Fit Measures | |||||||

| NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | PRATIO | PNFI | PCFI | |

| Criteria | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.50 | ≥0.50 | ≥0.50 |

| Obtained | 0.938 | 0.927 | 0.956 | 0.948 | 0.956 | 0.844 | 0.792 | 0.807 |

| Factor | Estimate/Weight | p Value | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Courtesy | 0.881 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Competency and Quality Instruction | 0.840 | 0.001 | 2 |

| Reliability | 0.796 | 0.001 | 3 |

| Access | 0.789 | 0.001 | 4 |

| Assurance | 0.780 | 0.001 | 5 |

| Tangible | 0.780 | 0.001 | 5 |

| Responsiveness | 0.765 | 0.001 | 6 |

| Reputation | 0.721 | 0.001 | 7 |

| Empathy | 0.679 | 0.001 | 8 |

| Communication | 0.606 | 0.001 | 9 |

| Orientation | 0.597 | 0.001 | 10 |

| Understanding the Customer | 0.527 | 0.001 | 11 |

| Name | Description | Global Weights | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Administrators’ ability to communicate in English and the availability of English programs for international students | 0.1300 | 1 |

| Understanding Customer | University management handling diversity, cultural awareness, inclusiveness and support | 0.1107 | 2 |

| Competence Quality Instructor | Lecturer’s teaching skills, creativity, the mood of delivery, classroom preparedness and assessment | 0.1056 | 3 |

| Access | University management availability to deal with international student issues and accessibility of the academic facilities | 0.1001 | 4 |

| Courtesy | Lecturers’ relationship with international students, academic support in studies/research and international students with the local community in Malaysia | 0.0993 | 5 |

| Responsiveness | Universities’ willingness to help international students and provide prompt service | 0.0961 | 6 |

| Reputation | University’s reputation/ranking/world recognition/image/collaboration | 0.0852 | 7 |

| Orientation | 0.0795 | 8 | |

| Assurance | Staff’s knowledge/courtesy/trust/confidence when offering services to international students | 0.0629 | 9 |

| Reliability | Keeping the promise or advertised services consistently over a period of time and handling students’ service problems. | 0.0551 | 10 |

| Empathy | Compassion and caring for international students | 0.0419 | 11 |

| Tangibles | The appearance of facilities, physical equipment, location, and the appearance of the institution’s personnel | 0.0337 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amzat, I.H.; Najimdeen, A.H.A.; Walters, L.M.; Yusuf, B.; Padilla-Valdez, N. Determining Service Quality Indicators to Recruit and Retain International Students in Malaysia Higher Education Institutions: Global Issues and Local Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086643

Amzat IH, Najimdeen AHA, Walters LM, Yusuf B, Padilla-Valdez N. Determining Service Quality Indicators to Recruit and Retain International Students in Malaysia Higher Education Institutions: Global Issues and Local Challenges. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086643

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmzat, Ismail Hussein, Abdul Hakeem Alade Najimdeen, Lynne M. Walters, Byabazaire Yusuf, and Nena Padilla-Valdez. 2023. "Determining Service Quality Indicators to Recruit and Retain International Students in Malaysia Higher Education Institutions: Global Issues and Local Challenges" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086643

APA StyleAmzat, I. H., Najimdeen, A. H. A., Walters, L. M., Yusuf, B., & Padilla-Valdez, N. (2023). Determining Service Quality Indicators to Recruit and Retain International Students in Malaysia Higher Education Institutions: Global Issues and Local Challenges. Sustainability, 15(8), 6643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086643